Carinthian Slovenes

The Carinthian Slovenes ( Koroški Slovenci in Slovenian ) is the name given to the autochthonous Slovenian-speaking ethnic group in the Austrian state of Carinthia . You send representatives to the Austrian national minority group and are mostly Austrian citizens . The status of the ethnic group is secured under constitutional and international law.

The term Carinthian Slovenes is not synonymous with the term Slovenes in Carinthia (see Slovenes in Austria )

history

Great Migration

Towards the end of the Great Migration, the Slovene-speaking area was first populated by Western Slavs, and then finally by Southern Slavs, who became the predominant group. A South Slavic colloquial language with West Slavic influence ( Alpine Slavs ) was created . At the end of the Great Migration, the Slavic state structure of Karantanien was created , the forerunner of today's Carinthia, which extended far beyond today's territory and whose political center was on the Zollfeld .

Middle Ages and Modern Times

Karantanija was Karl the large part of the CHF - and consequently of the Holy Roman Empire as to give parallel to the Middle Ages two legal systems considered, such as the so-called Slawenzehent ( huba slovenica ) and in particular the prior Edlinger (Slovenian kosezi show) . As a result, German aristocratic families gradually prevailed, while the population remained Slavic. Finally, a settlement movement from the Bavarians to Carinthia began. These were previously sparsely populated areas, such as forest areas and high valleys. The immediate displacement of Slavs (as Slovenes they only emerged in the course of time) only occurred occasionally. As a result, a language border developed which remained stable until the 19th century. During this time, German played a dominant role in Klagenfurt in terms of society and the sociology of language, while the immediate vicinity remained Slovenian. Klagenfurt was also an all-Slovenian cultural center and was the Slovenian book town. With the emergence of the national movement in the late monarchy, assimilation accelerated, at the same time the conflict between the ethnic groups intensified.

After 1918

At the end of the First World War , the SHS state tried to occupy the areas that had remained Slovene (compare Carinthian defensive battle ). This question also divided the Slovenian population. In the voting zone, in which the Slovene-speaking proportion of the population was around 70%, 59% of the voting participants voted to stay with Austria. In the run-up to the referendum, the state government assured that it would support and promote the preservation of Slovenian culture. These conciliatory promises, along with economic and other reasons, resulted in around 40% of the Slovenes living in the voting zone in favor of maintaining national unity. The voting behavior, however, differed from region to region; In numerous municipalities there were majorities in favor of joining the SHS state.

The Slovene ethnic group in Austrian Carinthia had minority rights until Austria was " annexed " to the German Reich in 1938. At first there were bilingual schools, parishes, their own newspapers, associations, banks and political representatives in communities and in the state parliament. The political tensions between Austria and Yugoslavia increased the disadvantage of the Carinthian Slovenes. As everywhere in Europe, nationalism increased in the interwar period . Promises made were broken, assimilation was forced by dividing the Slovenes into Slovenes and Windisch , even denying them that their language was Slovenian at all (cf. “ Windisch theory ”). This culminated in targeted persecution in the Third Reich. However, by confessing to Windischen and the associated promise to assimilate with the regime one could do well. Conversely, many of the Slovenes who voted for Yugoslavia in 1920 despised the “nemčurji” (a derogatory term for Slovenes who are allegedly German national or deny their national origin).

The deportation of the Carinthian Slovenes began on April 14, 1942. This was preceded by an order from Himmler on August 25, 1941, in which he also determined the resettlement of the Kanaltaler to Carinthia, Upper Carniola and the Mießen Valley . When they were resettled, Carinthian Slovenes were deported to the RAD camp in Klagenfurt and from there to various camps of the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle . The deportation aroused strong support for the armed resistance from the Slovenian population, many went into the forests, formed the Green Cadre and later joined the Titopartisans . After the war they tried again to occupy parts of Carinthia, but withdrew at the urging of the British occupiers. In view of this extreme development on both sides, the mood between the ethnic groups was extremely tense after the Second World War. The steady suppression of Slovenian continued.

After 1955

On May 15, 1955, the Austrian State Treaty was signed, Article 7 of which regulates the “rights of the Slovenian and Croatian minorities” in Austria. In 1975 the electoral grouping of the Slovene ethnic group ( Enotna Lista ) only narrowly missed entry into the Carinthian state parliament . Before the next elections in 1979, the originally unified Carinthia constituency was divided into four constituencies. The settlement area of the Carinthian Slovenes was divided and these parts in turn combined with purely German-speaking parts of the country. In the new constituencies, the Slovene-speaking proportion of the population was reduced to such an extent that it was no longer possible for representatives of the minority group to enter the state parliament. The ethnic group office of the Carinthian provincial government and representatives of the Carinthian Slovenes saw this procedure as a successful attempt to reduce the political influence of the Slovenian-speaking ethnic group.

In the 1970s the situation escalated again in the so-called local sign dispute , after which it relaxed again. However, the situation of the Slovenes in Carinthia changed fundamentally when Slovenia declared independence on June 25, 1991 . Unlike the pan-Slavic state of Yugoslavia, from which Slovenia broke away in 1991, the Republic of Slovenia is designed as a nation-state. Logically, there is a “Ministry for Slovenes Abroad” in Slovenia, which is also responsible for the concerns of autochthonous Slovenes in Carinthia. In February 2017, the Slovenian Foreign Minister Karl Erjavec criticized the fact that the new constitution of Carinthia discriminated against the Slovenian language as it was not considered "the language of the execution of the Province of Carinthia".

Settlement area

| year | number | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1818 | 137,000 | |

| 1848 | 114,000 | Estimate of the provincial committee - within the then limits of the Duchy of Carinthia |

| 1880 | 85.051 | Census - within today's limits, the question was asked about the colloquial language |

| 1890 | 84,667 | Colloquial language |

| 1900 | 75,136 | Colloquial language |

| 1910 | 66,463 | Colloquial language |

| 1923 | 34,650 | Language of thought |

| 1934 | 24,875 | Belonging to the culture |

| 1939 | 43.179 / 7.715 | Mother tongue / ethnicity |

| 1951 | 42,095 | Colloquial language |

| 1961 | 24,911 | Colloquial language |

| 1971 | 20,972 | Colloquial language |

| 1981 | 16,552 | Colloquial language |

| 1991 | 16,461 | Colloquial language |

| 2001 | 12,586 | Colloquial language |

At the end of the 19th century, the Carinthian Slovenes made up about a quarter to a third of the total population of Carinthia within the borders of that time. In the course of the 20th century, their number fell to officially 2.3% of the total population, mainly due to the pressure to assimilate.

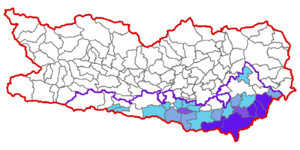

Since German predominated from the west and north, today's settlement area is in the south and east of the country, in the Jaun - Keutschacher and Rosental , in the lowest Lavant valley and in the Gail valley (up to around Hermagor-Pressegger See ). The northernmost points are about Köstenberg and Diex .

In 1857 K. v. Czoernig described the German-Slovenian language border in his ethnography of the Austrian monarchy as follows: Malborghet - Möderndorf / Hermagor - Gail / Drau watershed - Villach - Zauchen - Dellach (near Feldkirchen ) - Moosburg - Nussberg - Galling - St. Donat - St. Sebastian - St. Gregorn (near Klein St. Veit ) - Schmieddorf - Wölfnitz / Saualpe - Pustritz - Granitztal - Eis (on the Drau) - Lavamünd (although the above mentioned localities were still in the German-speaking area). The provincial capital Klagenfurt, the Zollfeld to the north of it and the cities of Bleiburg and Völkermarkt in southern Carinthia were also predominantly German-speaking. Expressed in numbers: In the middle of the 19th century, 95,735 people spoke Slovene (30%) and 223,489 German (70%) as the colloquial language within the then borders of Carinthia.

In 2010 the vocabulary of the Slovenian field and farm names in Carinthia was included in the list of intangible world heritage sites as declared by UNESCO in the list of Austria (national cultural property) .

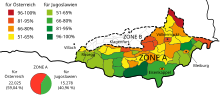

Population share

The municipalities with the highest proportion of Carinthian Slovenes are Zell (89%), Globasnitz (42%) and Eisenkappel-Vellach (38%) (according to the 2001 census).

The actual number of Carinthian Slovenes is controversial, as both representatives of Slovenian organizations and representatives of traditional Carinthian associations describe the results of the census as inaccurate. The former point to the sometimes strongly fluctuating census results in individual municipalities, which, in their opinion, correlate strongly with political tensions in ethnic group issues. Thus the results would underestimate the actual number of Carinthian Slovenes. For example, reference is made to the southern Carinthian municipality of Gallizien , which, according to the 1951 census, had a Slovene-speaking population of 80%, but in 1961 - with the simultaneous absence of major migratory movements and roughly the same population - only 11%.

Another example is the results of the former municipality of Mieger (now part of the municipality of Ebenthal ), which in 1910 and 1923 had a Slovene-speaking proportion of the population of 96% and 51% respectively, but only 3% in 1934. After the Second World War and a relaxation in the relationship between the two ethnic groups, the community again showed 91.5% in 1951. Finally in 1971 (in the run-up to the so-called Carinthian local sign tower ) the number of Slovenes fell again to 24%. Representatives of the Carinthian Slovenes see the results of the census as the absolute lower limit. They refer to a survey carried out in 1991 in bilingual parishes in which the parishioners were asked about the colloquial language of the parishioners. The result of the survey (50,000 members of the national minority) differed significantly from the results of the census that took place in the same year (approx. 14,000).

Carinthian traditional associations estimate the actual number of professing Slovenes at 2,000 to 5,000 people.

| 1971 census | 2001 census | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Color legend: |

Dialects

literature

In the spring of 1981 the novel “Der Zögling Tjaž” by Florjan Lipuš was published in the German translation by Peter Handke . For this literary achievement, Peter Handke was referred to by the Wiener Extrablatt as "personified article seven". In addition to Lipuš, Handke later translated Gustav Januš .

The Carinthian Slovenian literature is not only made up of Lipuš and Januš, but also a number of other authors. The tradition includes Mirko Kumer , Kristo Srienc and Valentin Polanšek . Lipuš Janko Messner is one of the smaller, more innovative, but still traditional groups . Lipuš himself has developed into an outstanding fiction writer.

Younger prose writers include Jože Blajs , the internationally known Janko Ferk , Martin Kuchling and Kristijan Močilnik .

The number of lyric poets is remarkable . Milka Hartman is outstanding . Anton Kuchling belongs to her generation . The next generation are Gustav Januš and Andrej Kokot as well as the poets who are silent today, namely Erich Prunč and Karel Smolle . These poets are followed by a group that has mainly formed around the literary magazine " mladje " . Janko Ferk, Maja Haderlap , Franc Merkac and Jani Oswald as well as Vincenc Gotthardt , Fabjan Hafner and Cvetka Lipuš are the associated names. The younger generation includes Rezka Kanzian and Tim O. Wüster .

Slovenian literature in Carinthia showed its clear will to live after the Second World War. Today it is an emancipated literature without any kind of provincialism.

From a literary sociological, theoretical and historical point of view, Johann Strutz (Janez Strutz) has rendered outstanding services to the literature of the Carinthian Slovenes. His Profiles of Modern Slovene Literature in Carinthia , published in 1998 by Hermagoras Verlag , Klagenfurt / Celovec, is a highly regarded standard work.

School system

School system until 1958

In 1848 the Ministry of Education decreed that compulsory school students should be taught in their respective mother tongue. The endeavor of German national forces in Carinthia to change this requirement was unsuccessful until the end of the 1860s. Between 1855 and 1869 the Slovene compulsory education system was in the hands of the traditionally Slovene-friendly Catholic Church . The requirements with regard to the use of the mother tongue in the classroom underwent a serious change in the Reichsvolksschulsgesetz of 1869 , since from this point on the school maintainer could determine the classroom language. This led to the conversion of a large part of the compulsory schools into so-called utraquist schools , in which Slovene was viewed as an auxiliary language that was only used in the classroom until the pupils had a sufficient command of the German language. Only a few schools remained purely Slovenian (1914: Sankt Jakob im Rosental , St. Michael ob Bleiburg and Zell-Pfarre ). The utraquist school system was retained until 1941. This school system was rejected as a "Germanization instrument" by the Slovenian ethnic group.

On October 3, 1945, a new school ordinance was passed that provided for bilingual education for all children in the traditional settlement area of the Carinthian Slovenes (regardless of their ethnic group). The bilingual lessons were to take place in the first three grades, after which Slovenian was planned as a compulsory subject. After the signing of the State Treaty in 1955 and the implicit solution of the previously open question of the course of the Austrian-Yugoslav border, protests against this model broke out, which culminated in school strikes in 1958. As a result of this development, Governor Ferdinand Wedenig issued a decree in September of the same year , which enabled the legal guardians to de-register their children from bilingual classes. In March 1959, the teaching system was changed again to the effect that from that point on, students had to register expressly for bilingual lessons. The number of students in the bilingual system fell considerably as a result of the compulsory confession. In 1958 only 20.88%, in the 1970s only 13.9% of bilingual students were registered for German-Slovenian lessons.

School system from 1982

The minority school law, which was amended in the course of a tripartite agreement (SPÖ, ÖVP and FPÖ), has provided for an extensive class-based separation of the bilingual and monolingual German taught elementary school students since 1982. To this day, the question of whether school principals in bilingual schools must have a bilingual qualification remains a controversial issue.

The described general development in the bilingual teaching system, viewed critically by Slovenian organizations, is offset by an expansion of the school offer: In 1957 the "Bundesgymnasium und Bundesrealgymnasium für Slovenes" (Zvezna gimnazija in Zvezna realna gimnazija za Slovence) was founded in Klagenfurt , in whose building since 1991 also the "Bilingual Federal Trade Academy " (Dvojezična zvezna trgovska akademija) is housed. Since 1989 there has been a denominational HBLA in St. Peter im Rosental ( St. Jakob parish ). According to a decision by the Constitutional Court , students in Klagenfurt have the option of attending a public bilingual primary school in addition to a denominational school.

The Slovenian "Carinthian Music School" (Glasbena šola na Koroškem) was founded on a private initiative in 1984 and has received public subsidies since a cooperation agreement concluded in 1998 with the Province of Carinthia. The amount of this financial support (allocated to the number of pupils), however, contradicts the principle of equal treatment in the opinion of the Austrian National Center for Ethnic Groups , since the second provider of the Carinthian music school system, the Music School Works, receives a higher amount on a per capita basis. The operation of the Glasbena šola can, however, be maintained with the help of grants from the Republic of Slovenia.

In general, there has been an increased interest in bilingual teaching among southern Carinthians in recent years. In the school year 2009/10, for example, 41.3% of primary school students in the minority school system were registered for bilingual classes (the proportion of children without any previous knowledge of Slovene is over 50%).

Awards

The Christian Cultural Association and the RKS annually donate the Einplayer Award (named after Hermagoras founder Andrej Ein Spieler ) for people who have made a contribution to living together. Carriers were u. a. the industrialist Herbert Liaunig and the linguist Heinz-Dieter Pohl .

The after is awarded jointly by the Slovene Cultural Association and the Central Association of Slovenian Organizations Vincent Rizzi named Vincent-Rizzi Award to individuals "the intercultural for the expansion of relations between the two ethnic groups in Carinthia pioneering work have done" .

The Julius Kugy Prize for merits in the Alps-Adriatic region is awarded by the Community of Carinthian Slovenes - Skupnost koroških Slovencev in Slovenk . The sponsors include Brigadier Willibald Liberda, Karl Samonig, Hanzej Kežar, Janez Petjak, Herta Maurer-Lausegger and Ernest Petrič.

Organizations

Minority organizations include:

- Carinthian Unity List (Koroška enotna lista) - political collective movement that competes in local elections

- Council of Carinthian Slovenes (Narodni svet koroških Slovencev) - Christian-conservative representation of interests

- Central Association of Slovenian Organizations in Carinthia (Zveza slovenskih organizacij) - left-wing interest representation

- Community of Carinthian Slovenes (Skupnost koroških Slovencev in Slovenk-SKS) - non-partisan representation of interests

- Christian Cultural Association (Krščanska kulturna zveza)

- Slovenian Cultural Association (Slovenska prosvetna zveza)

- Slovenian Business Association (Slovenska gospodarska zveza)

- Community of South Carinthian Farmers (Skupnost južnokoroških kmetov)

- Slovenian Alpine Club Klagenfurt (Slovenska Planinska Družba Celovec)

- Slovenian Athletics Club (Slovenski atletski klub)

- Koš Celovec / Klagenfurt - basketball club

- Carinthian Schools Association ( Koroška dijaška zveza )

- Club of Slovene Students Graz (Klub slovenskih študentk in študentov Gradec)

- Club of Slovene Students in Vienna (Klub slovenskih študentk in študentov na Dunaju)

- Club of Slovene Students in Carinthia (Klub slovenskih študentk in študentov na Koroškem)

media

- Nedelja - Slovenian-language weekly newspaper of the Diocese of Gurk

- Novice - Slovenian-language weekly newspaper (Klagenfurt), published jointly by the Council of Carinthian Slovenes and the Central Association of Slovenian Organizations in Carinthia

- Mohorjeva družba-Hermagoras - Catholic bilingual publisher (Klagenfurt)

- Drava Verlag - bilingual publisher in Klagenfurt

- Wieser Verlag - bilingual publisher in Klagenfurt

- Radio AGORA - bilingual free radio in Klagenfurt

Well-known Carinthian Slovenes

Well-known Carinthian Slovenes under the category: Carinthian Slovenes

literature

- Moritsch Andreas (Ed.): Kärntner Slovenen / Koroški Slovenci 1900–2000 - Unlimited history - zgodovina brez meja 7 . Hermagoras / Mohorjeva, Klagenfurt 2003, ISBN 3-85013-753-8 .

- Wilhelm Baum (Ed.): Like a bird locked in a cage. The Diary of Thomas Olip. Kitab-Verlag , Klagenfurt 2010, ISBN 978-3-902585-56-1 .

- Wilhelm Baum: The Freisler Trials in Carinthia. Evidence of resistance against the Nazi regime in Austria. Kitab-Verlag, Klagenfurt 2011, ISBN 978-3-902585-77-6 .

- Wilhelm Baum: Sentenced to death. Nazi justice and resistance in Carinthia. Klagenfurt 2012, ISBN 978-3-902585-93-6 .

- Albert F. Reiterer: Carinthian Slovenes: Minority or Elite? Recent tendencies in the ethnic division of labor . Drava Verlag / Založba Drava, Klagenfurt 1996, ISBN 3-85435-252-2 .

- Katja Sturm-Schnabl, Bojan-Ilija Schnabl (eds.): Encyclopedia of Slovenian cultural history in Carinthia / Koroška. From the beginning to 1942. Three volumes. Volume 1 (A – I), Volume 2 (J – Pl), Volume 3 (Pm – Z), Böhlau, Vienna 2016

- Reginald Vospernik : Driven from home twice. The Carinthian Slovenes between 1919 and 1945. A family saga. Kitab-Verlag, Klagenfurt 2011, ISBN 978-3-902585-84-4 .

Web links

Politics:

- Website of the national minority group office of the Province of Carinthia

- Carinthian standard list

- Council of the Carinthian Slovenes

- Central Association of Slovenian Organizations

- Community of Carinthian Slovenes

- Interview with the former chairman of the Council of Carinthian Slovenes Bernhard Sadovnik

Culture and History:

- slolit.at Internet encyclopedia of Carinthian Slovenian literature

- Slavic Austria - Past and present of the minorities, The Slovenes in Carinthia (pdf; 6 kB)

- Brochure about the history and current situation of the Carinthian Slovenes (pdf; 91 kB)

- The poetry of the Carinthian Slovenes in the twentieth century - by Janko Ferk

- SLOV-ONLINE archive - collection of the most important messages since the beginning , message archive volksgruppen.orf.at (since May 2000)

- Website by Heinz-Dieter Pohl :

Individual evidence

- ↑ Werner Besch u. a. (Ed.): History of language. A handbook on the history of the German language and its research. Volume 4, Berlin 2004, p. 3370.

- ↑ Janez Wutte: We were the Chushes and they were the švaba . Documentation of the Austrian resistance

- ^ Valentin Sima: Carinthian Slovenes. In: E. Talos, E. Hanisch, W. Neugebauer (eds.): NS rule in Austria 1938–1945. Vienna 1988, ISBN 3-900351-84-8 , pp. 361-379.

- ^ Carinthian constitutional reform unacceptable for Slovenes . The standard . 17th February 2017

- ↑ Karl Freiherr von Czoernig: Ethnography of the Austrian monarchy . 1857, p. 27.

- ↑ Slovene field and farm names in Carinthia ( memento of the original from October 29, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . nationalagentur.unesco.at

- ↑ see slolit.at

- ↑ a b c d e Office of the Carinthian Provincial Government - Ethnic Group Office (ed.): The Carinthian Slovenes. 2003.

- ↑ a b Heinz Dieter Pohl: The ethnic-linguistic requirements of the referendum (accessed on August 3, 2006)

- ↑ a b Christina Bratt Paulston, Donald Peckham (ed.): Linguistic minorities in Central and Eastern Europe . Multilingual Matters, Clevedon 1998, ISBN 1-85359-416-4 , pp. 32 f .

- ↑ Report of the Austrian Center for Ethnic Groups on the Implementation of the European Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities in the Republic of Austria Part II (accessed on August 3, 2006)

- ↑ Standard list: Record number of registrations for bilingual classes in Carinthia . Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ Vinzenz Rizzi Prize to Karl Stuhlpfarrer. Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt , accessed on December 2, 2010 .

- ↑ For a more detailed list see the Slovenian ethnic group in Austria , Embassy of the Republic of Slovenia in Vienna, dunaj.veleposlanistvo.si