Autumn of the Middle Ages

Autumn of the Middle Ages is the title of a work by the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga on Flemish - Burgundian culture of the 14th and 15th centuries, which was first published in 1919, then reprinted several times and published as the last edition in 1941 , and which has become a classic in cultural history. The book has been translated into numerous languages and has had an enormous impact. In Germany the first edition was published in Munich in 1924 and the 12th edition in 2006 by Alfred Kröner Verlag and a new translation in 2018.

The statements and findings of the work are significant beyond the region of Flanders and Burgundy, as similar moods and currents in the German late Middle Ages u. a. by Walther Rehm and - albeit with a different methodological approach and a strongly nationalistic orientation - by Rudolf Stadelmann .

History and methodological approach

Huizinga was very impressed by the exhibition Les Primitifs Flamands à Bruges in 1902 on so-called primitive Flemish painting of the late 14th and early 15th centuries in Bruges , namely by Jan van Eyck's paintings , about whom he began to write a book . The autumn of the Middle Ages developed from its beginnings . While he was working on it, he turned away from linguistics and towards (cultural) history. Around 1907, Huizinga realized that the late Middle Ages were “not the announcement of something to come, but the withering away of what is going”, which was completely contrary to the knowledge of the time. The culture of this time is not the "Advent of the Renaissance"; this applies not only to artists, but also to poets and theologians.

With this thesis he came in contradiction to Jacob Burckhardt , who saw in his work "The Culture of the Renaissance in Italy" in the culture of the Renaissance a modern, strongly secular phenomenon. Huizinga was critical of Burckhardt's fixation on the Italian Quattrocento . Because of this, he neglected late medieval life in other countries. However, this was not fundamentally different from that of Italy in the 15th century.

The criticism of Burckhardt's understanding of an early “bloom” of modernity is reflected in Huizinga's work and above all in the choice of the “autumn” metaphor . In contrast to the assumption of a “golden age”, which was widespread not least under Burckhardt's influence, this suggests a re-bloom and a subsequent cultural decline of the previous epoch.

Huizinga's pictorial thinking, his morphological approach, which led him to search for the inner homogeneity of cultures and epochs, shows certain parallels to Oswald Spengler's work The Downfall of the Occident . However, he did not share his fatalism and basic biological and racial assumptions. Huizinga was also aware of the problems of the autumn metaphor: it should only reflect the “mood of the whole”, the transitory, fleeting nature of this time, so it does not represent a morphology of doom as Spengler designed. In contrast to Norbert Elias , Huizinga does not want to describe a teleologically oriented process at all . The dynamic of the political forces also remains largely outside the scope of the work.

Huizinga, however, implicitly distinguished himself from the cultural historian Karl Lamprecht , whose use of epochal and guiding terms he criticized: historical guiding terms are always subordinate to the concrete interpretation; Epochs are not delimited by years, rather their long-term effects are relevant. Huizinga only accepted Lamprecht's psychological-materialistic interpretation of cultural phenomena for the motives of individuals to act. But in feudal times, when greed was only gradually seen as one of the most important deadly sins due to a lack of movable wealth, these could also be derived from a gloomy greed for revenge, greed for power and injured arrogance. The arrogance and the lust for fame went hand in hand in the form of the waste of a marriage with the growing greed. In the conflict between the Houses of Orleans and Burgundy, blood revenge was not the only, but a decisive factor.

The cultural scientist Franz Arens dealt with Huizinga's method like few others. He saw in Huizinga an idealistic spirit fighting against the windmill wings of political and economic explanations and the dominance of the corresponding documents, which betray nothing of the "difference in the tone of life that separates us from those times," while most historians that of Huizinga still ignored the type of narrative and pictorial sources used.

Unlike the history philosopher Frank Ankersmit, Christoph Strupp only at first glance sees Huizinga's method as being related to the postmodern understanding of science, which reduces history to metaphors and forms. In fact, his ethos of truth and the cultural significance of the humanities, which he valued, separate him from postmodern science.

content

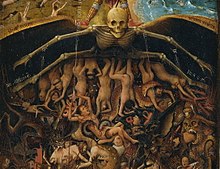

The starting point of the work is the diagnosis of a high "tension in life", a strong emotionalization of society in the late Middle Ages, which was associated with a more extreme experience of happiness and unhappiness than was normally the case in modern times. The time at that time appears as an era of extreme passions, shaped by wars, diseases, insecurity and fear of life, fear of the Turks and the plague, contempt for the world, fatalism, hysteria and asceticism as well as the aristocracy's lust for pleasure and opulence. The “basic tone” of the history of the Burgundian princely house, which runs like a red thread through the work, is the “greed for revenge”; this is the motive for numerous party struggles, behind which no economic causes are discernible, but a largely still pagan sense of justice, according to which every act must result in retribution. On the other hand, the notion that all crimes could be atoned for disappeared, since every crime was seen as an attack on the majesty of God.

Everything was noisy in public light: religious rituals and sacraments, processions and ringing bells, sacrilege (such as the Bal des Ardents ), barbaric executions that were pursued with perverse lust or "animal, jaded delight", the most cruel harshness against the needy, the disabled and the mentally ill, as well as feudal ostentation as well as boundless emotion, public sermons against luxury, repentant renunciation, mass confessions and penances were omnipresent. Loyalty to the princes and party feelings triggered the strongest emotions. Life was more colorful and exciting, the general "irritability" greater than it is today, the "willingness to cry" omnipresent, which Huizinga tries to prove with numerous characteristic episodes:

"When the famous Olivier Maillard gave the sermons of Lent in Orléans in 1485, so many people climbed on the roofs of the houses that the slater later charged 64 days for restoration work."

In the context of the history of mentality, the refined late Gothic religious and secular art played an important, emotionally deeply moving role; On the one hand it served the religious and secular edification and display of splendor, on the other hand the escape from the God-given harsh reality of life, especially of the lower classes, since there was hardly any relief for poverty, illness, cold and darkness. The world of the lower classes was one of misery, intoxication and belief in miracles. Court society, on the other hand, shaped its emotions in style; their elaborate rituals and their romantic idylls formed a protective shield against the increasing violence and brutality of society, but occasionally the bearers of court culture also fell back into barbaric behavior or turned away, disappointed, from the "cowardly, pathetic and limp" world like the fashion poet at the French court of Eustache Deschamps .

While the people lived in the "meander of a completely alienated religion" and there were awkwardnesses and drinking feasts during processions, enthusiasts like Dionysius the Carthusian nourished the tendency to mysticism with his devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus , which led to the return to a pre-intellectual life of the soul and world denial promoted.

"The Council of Strasbourg had 1,100 liters of wine served annually to those who spent St. Adolf's Night in the cathedral" while watching and praying. "

The saints were still present in everyday life and not raptured; the people, clinging to material things, also took hold of them in physical form.

"Occasionally a feast Charles VI distributes. Ribs of his ancestor, St. Ludwig [...], the prelates are given a leg to distribute, which they then do after the meal. "

The image of this extremely colorful late medieval culture, dominated by brutal violence and permanent fear of death, but also world denial and the "longing for a more beautiful life" - at least in dreams - is vividly, even suggestively, expounded by Huizinga.

The decline of the knight thought played a central role in the epoch . Huizinga shows how this general longing for a more beautiful life is expressed in refined art and literature, in glamorous court ceremonies at the court of Burgundy, in religious rituals and in pastoral idylls, while at the same time the aristocratic ideal of knight and love and the dreams of Heroism has long since degenerated into an illusion: the knightly world already lost its military importance and its ethical ideals by the time of Charles the Bold ; the duel has given way to the technique of sneaking up and being taken by surprise. The world of knights becomes an idyllic fairytale world, it is dreamed of. “Chivalry takes things all the more seriously, the more unreal they threaten to become [...] In this world things are asked once again about their meaning, not about their being. On the tournament ground, the symbolism of the Middle Ages defends itself against the realism of the modern age. "

Accordingly, the thinking of the time is subject to profound changes. Behind what Karl Lamprecht called “typism” of medieval thought does not conceal the “inability to see the uniqueness of things”, but the division of the whole world and its classification in hierarchies of terms. In painting and literature there is a tendency towards “unlimited elaboration of the details”. Profane objects on the panels of the Ghent Altarpiece arouse the same admiration as the religious symbolism: everything is essential, there is no difference between the subject and the accessories. The basic trait of the medieval spirit that appears in it is for Huizinga its "excessively visual character", a downside is the "atrophy of thought".

The complex, ultimately anthropomorphic, symbolic thinking of the Middle Ages escalates towards the end of the epoch into a schematic system of meanings in which everything is connected to everything by analogy ; the well-structured world of symbols is replaced by a highly coarsened pictorial-allegorical thinking of the lower classes on the one hand, which serves the superficial imagination, and on the other hand the blossoming of the concrete-realistic thinking of the Renaissance and the merchants. The bearers of the new, however, are not the representatives of Latinity and pompous rhetoric, which becomes a game of the educated, but rather those impartial, such as poets like François Villon

reception

Translations appeared in 1924 in German and in English, 1927 in Swedish, 1930 in Spanish, 1932 in French, 1937 in Hungarian, 1940 in Italian, 1951 in Finnish, 1961 in Polish, 1962 in Portuguese and 1995 in Russian. The question was repeatedly discussed whether “autumn” was a suitable metaphor for the epoch, ie whether it was more a phase of early bourgeois awakening rather than late feudal decadence and a decaying knightly culture. Questions about the epoch boundary between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance were also often raised. The work apparently contributed to an improved understanding of the individual development steps of the late medieval and early Renaissance culture.

It was also discussed how far Huizinga had moved away from the sources with his speculative-interpretive approach. It was occasionally commented critically that he did not have sufficient insight into the German situation. Many German researchers, however, felt strongly drawn to the work. Walther Rehm, who was enthusiastic about Huizinga's work, attested to him that the culture of late medieval Germany showed great parallels to the culture of Flanders and Burgundy. Friedrich Baethgen judged that Huizinga had captured the “general signature of time”. Gerhard Ritter , on the other hand, criticized the fact that the “worldly mercy” of declining chivalry as captured by Huizinga was “no evidence of a medieval doom and gloom par excellence”. Other authors accused Huizinga of being too fixated on the culture of the French or Burgundian court, but also of unclear conceptualization and the fuzzy territorial delimitation of the examined area. He occasionally borrows his examples from the English, Italian or German history of this time or goes back to the year 1000. Franz Ahrens considered the title of the book to be justified due to his knowledge of the Quattrocento in Western Europe.

A decidedly culture-critical interpretation, according to which Huizinga the late Middle Ages from the perspective of modern cultural criticism - z. B. under the impression of the doom and gloom of the 1930s - as Franz Schnabel suggested, Christoph Strupp considers it unfounded. However, parallels are often drawn with the culture of the Fin de Siècle (around 1890-1914), a time in which the (especially late) Middle Ages were exuberantly loved, idyllic, but at the same time viewed as a dying era.

For some decades now, the development of historical studies has increasingly been fed by ideas from other disciplines: from theories of culture, literature, art history or anthropology. The Huizingas plant can be regarded as groundbreaking for this development. This is especially true of his influence on the Annales School , which turned away from the history of events. Its founder Marc Bloch explicitly praised Huizinga's methodology. He sees the work as a pioneering contribution to the historical psychology of the collective, which, despite its sensitivity to the mental differences between the Middle Ages and modern times, neglects class differences.

Erich Auerbach deals with the phenomena pointed out by Huizingas from a style-critical perspective. He sees it in the tradition of the Middle Ages: the "strong color of the sensual taste of that time", the haunting sensuality of the "pompous style" shows the presence of the events of salvation history in the daily life of the people, but with signs of blatant "exaggeration" and "raw depravity". Even the dances of death have the character of processions or pageants. Auerbach calls the realism of the Franco-Burgundian culture of the 15th century, which "strongly emphasizes what is subject to suffering and transience", as "creatural"; the differences between the classes would be blurred by the common fate of creature decay. From this a strong counterweight against the humanistic imitation of antiquity grew.

expenditure

Dutch:

-

Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen: Study over levens- en gedachtenvormen der veertiende en vijftiende eeuw in Frankrijk en de Nederlanden . 1919.

- 21st edition Amsterdam, Antwerp 1997, ISBN 90-254-9625-3 .

- Edition in the Gesammelte Werken 1949 part 3 online dbnl .

German:

- Autumn of the Middle Ages: Studies of the 14th and 15th Centuries of Life and Spiritual Forms in France and the Netherlands. Edited by Kurt Köster. German by T. Wolf-Mönckeberg. Drei Masken Verlag Munich 1924. Improved new editions in 1928 and 1930 (the latter in the Kröner Verlag).

-

Autumn of the Middle Ages: Studies of Life and Spiritual Forms of the 14th and 15th Centuries in France and the Netherlands. After the edition of the last hand of 1941 ed. by Kurt Köster. Alfred Kröner Verlag, Stuttgart 1987.

- Paperback edition: 12th revised. and newly introduced edition Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-520-20412-7 .

- Autumn of the Middle Ages: Study of life and thought forms of the 14th and 15th centuries in France and the Netherlands. New translation. Wilhelm Fink Verlag 2018. ISBN 978-3-7705-6242-8 .

literature

- Christian Krumm: Johan Huizinga, Germany and the Germans. Waxmann Verlag, Münster / New York 2011.

- Christoph Strupp: Johan Huizinga: History as cultural history. Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht Verlag, Göttingen 2000.

- "Autumn of the Middle Ages"? Questions about evaluating the 14th and 15th centuries. Ed .: Jan A. van Aertsen, and Martin Pickavé. Miscellanea Mediaevalia 31. E-Book. Berlin, New York 2008. ISBN 978-3-11-020454-4

Individual evidence

- ^ Walter Rehm: Kulturverfall and late Middle High German didactics. Journal for German Philology 52, 1927.

- ↑ Rudolf Stadelmann: On the spirit of the late Middle Ages. Hall 1929.

- ↑ Hans Senger: A swallow doesn't make an autumn. On Huizinga's metaphor of the autumn of the Middle Ages. In: Questions about the evaluation of the 14th and 15th centuries , pp. 3–24. doi.org/10.1515

- ↑ Huizinga in the preface to the 1st German edition, reprinted in: Huizinga 1987, p. XI.

- ↑ The selection of pictures is not based on the works discussed by Huizingas or on a specific edition of the book.

- ^ Jacob Burckhardt: The culture of the Renaissance in Italy. Basel 1860.

- ↑ Oswald Spengler: The decline of the occident: Outlines of a morphology of world history. Volume 1: Shape and Reality. Vienna: Braumüller, 1918.

- ↑ Huizinga in the preface to the 1st German edition, reprinted in: Huizinga 1987, p. XI.

- ^ Norbert Elias: About the process of civilization , first published in 1939.

- ^ Johan Goudsblom: On the background of Norbert Elias' theory of civilization: their relationship to Huizinga, Weber and Freud. In: W. Schulte (Ed.): Sociology in Society: Papers from the events of the sections of the German Society for Sociology, the ad-hoc groups and the professional association of German sociologists at the 20th German Sociologists' Day in Bremen 1980 , Bremen 1981, Pp. 768-772.

- ↑ Krumm 2011, p. 254.

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, pp. 16, 24 f.

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, p. 10.

- ^ Franz Ahrens: Review in Archives for Politics and History VI (1926), p. 521.

- ↑ Strupp 2000, p. 293.

- ↑ All quotations from the German edition published by Kröner Verlag, Stuttgart 1987. Here: p. 1.

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, p. 16.

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, p. 16.

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, p. 8.

- ↑ Plebeian Franciscan and theologian, who fearlessly the atrocities of Louis XI. ( le Diable ) scourged; see short biography .

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, p. 6.

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, p. 33.

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, p. 205.

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, p. 187.

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, p. 194.

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, p. 29.

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, p. 67 ff.

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, p. 81 ff.

- ^ Hermann Hempel: Charles the Bold and the Burgundian State. In: Ders .: Aspects: Old and new texts. Wallstein Verlag 1995, p. 21.

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, p. 252.

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, p. 339.

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, p. 341.

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, p. 57 ff.

- ↑ Huizinga 1987, p. 385 ff.

- ↑ See numerous articles in Jan A. van Aertsen and Martin Pickavé 2008.

- ↑ Krumm, p. 116. A quintessence of the most important reviews of the German edition can be found in Christoph Strupp: Johan Huizinga: Geschichtswwissenschaft als Kulturgeschichte. Göttingen 2000, p. 143 ff.

- ↑ Baethgen and Ritter quote. according to Strupp 2000, p. 144.

- ↑ E.g. Huizinga 1987, p. 13.

- ↑ E.g. Huizinga 1987, p. 194.

- ^ Franz Ahrens: Western Europe Quattrocento. In: Hochland 23 (1925), no. 1.

- ↑ Strupp 2000, p. 257.

- ↑ Meindest Evers: Encounters with German Culture: Dutch-German Relations between 1780 and 1920. Königshausen & Neumann, 2006, p. 167.

- ↑ Christoph Strupp: The long shadow of Johan Huizingas. New approaches to cultural historiography in the Netherlands. In: Geschichte und Gesellschaft , 23 (1997) 1 ( Paths to Cultural History ), pp. 44–69.

- ^ Marc Bloch: La société féodale . 1939/40.

- ↑ Marc Bloch: Rezenstion of Huizinga, Johan: Autumn of the Middle Ages, Munich, Three masks-Verlag, 1928. In: Bulletin de la Faculté des Lettres de Strasbourg , 7 (1928) 1, pp 33-35.

- ↑ Erich Auerbach: Mimesis. (1946) 10th edition, Tübingen, Basel 2001, p. 236.

- ↑ Auerbach 2001, p. 237.