Chinese culture

As a Chinese culture ( Chinese 中華 文化 / 中华 文化 , Pinyin Zhōnghuá wénhuà ), the entirety of the cultural aspects specifically encountered in China such as ways of thinking, ideas and conceptions as well as their implementation in everyday life, in politics , in art , literature , painting , music and other areas of human life. That is, it is the totality of all forms of life in the ethnological sense. To a considerable extent, Chinese culture has influenced the cultures of other East and Southeast Asian countries such as Japan , Korea and Vietnam in particular, and was in turn influenced by them.

root

Chinese culture has three origins: the Yellow River civilization, the Yangtze River civilization, and the Nordic steppe culture . With regard to thinking, social life and its effective values and perspectives, it is rooted in a number of different ideological or philosophical traditions that show a diverse picture of China in connection with geographical, ethnic, historical and political conditions. In the present, changes are taking place in all areas, the effects of which are neither predictable nor foreseeable.

The actions of the actors are likely to be shaped by how changes have been managed in the past, according to the sinologist Schmidt-Glintzer. Members of Western societies find it difficult to understand how completely open the Chinese are with their "New China" concept. But the discourse about it began long ago.

Common ideals and a multi-ethnic state

China, which is almost ten million square kilometers in size and whose inhabitants came to China thousands of years ago over a period of centuries from the areas around it today, appears homogeneous at first glance. Its current residents - according to the authors of a China handbook - agree that the same basic ideals apply to them in terms of culture, religion and society. According to Schmidt-Glintzer , it is conceivable that this uniformity is due to the Chinese writing culture, which gave rise to the idea of a Chinese culture . About 92% of the residents see their roots in the time of the Han Dynasty at the beginning of the Christian era. Other peoples such as the Hui , Mongols , Manchu and Zhuang and many others of the total of 56 peoples are residents of China. Minorities are expected to fit in if they want a future in this country. But China was never a nation in the European sense, but a world shared by many peoples, or "a cultural area in Eastern Asia" with a permeable border. Relationships with neighbors were presumably mostly maintained on an equal footing.

In addition, the geographical and above all the agricultural conditions of the country are considered to be the forming factors of a way of life common to most of the residents, which has shaped the everyday attitudes and lifestyle of the residents for centuries. Sinologists also count China's "irrigation system" as one of these defining conditions, through which sufficient harvests were made possible in the country with little rainfall and traffic routes were created that benefited the residents and created an infrastructure that promotes community. The family system, which worked well into the 20th century and was one of the best organized in the world, was also very effective in terms of social policy. Values that were developed and lived through the relationships between family members have successfully shaped social relationships and developments. It is even said that the Chinese advanced civilization is the only one of the early advanced civilizations that lives on through the various social changes and with them. According to Schmidt-Glintzer , the past is also effective in the present and the present of China can only be understood in the discourse on the past.

Three worldviews

In the 2nd millennium BC When the Shang dynasty ruled, the world view of the inhabitants living at that time was shaped by shamanistic beliefs and belief in natural gods (sun, moon, earth, mountains, clouds, rivers, etc.). Ceremonial acts, above all oracle inquiries for questions about the future and interpretations of appearances of the natural gods (such as star constellations) were practiced, which were experienced by the individual and the community as help and support for everyday life (see also Fangshi ). Ideas from these practices had an impact in later manifestations of Chinese culture, especially popular belief, and to this day in the fear of ghosts. The worship of ancestors and the need for a natural way of life in harmony with the cosmos probably began in them.

According to Schmidt-Glintzer, the religious culture of the Shang became the basis of "all Chinese culture of the later centuries," which was tied to the structure of the state and the individual way of life of the people. She thematized a world of gods, a world of ancestors and a world of the living. These worlds and their interaction gave rise to philosophical-political reflections in the subsequent Zhou period . The ideas of nature deities changed over centuries under Confucian and Daoist activities to more abstract ones, such as that of "heaven" (天tian ), which could serve as a location for "everything under heaven" for the territory of the Chinese emperor. Together with the practice of traditional rituals, it formed the Chinese conception of the world until the 19th century.

In the 5th century BC Chr. Was created in the wake of wars in the Warring States Period of Confucianism is often regarded as the epitome of Chinese culture ever. This philosophy teaches responsible self-control through learning, which should benefit social life. Confucianism took up traditions at the same time - the z. B. concerned agricultural processes and relationships between landlords and farmers - in order to maintain the continuity of everyday life. According to Feng Youlan , Confucianism is the philosophy of social design and therefore it has also become the philosophy of everyday life. He encouraged people to be socially responsible by promoting proven human relationships as the foundation of society.

Daoism , which was founded by Laozi about fifty years earlier, focuses on the life of every person in harmony with nature and stimulates what functions naturally and spontaneously in people. In this way, it also gave individuals the opportunity to escape the pressure of society and to shape their lives according to their own values. Han Feizi propagated shortly before the turn of the century around 200 BC. After centuries of war between competing tribal chiefs, legalism : "Even if some extraordinary people can be successfully ruled with kindness, the majority still needs control by the law." () Said legalists.

Under the rule of the Qin dynasty , this philosophy became, according to its idea, a means to induce people to lead a life in conformity with the state through control and punishment. It served in the Qin period for the first time in the classical period of an administrative policy exclusively determined by the emperor. B. carried out unauthorized and compulsory standardizations of measurements and weights, the currency and the writing. According to Schmidt-Glintzer, the new type of administrative policy has developed into an effective state idea in the long term, although it contradicts the Chinese tradition of individual activity and personal responsibility ( subsidiarity ):

The rule of the Qin ended in 209 BC. Under the uprisings of the peasants. In the subsequent Han period, Confucianism became a generally accepted philosophy. In Confucianism, preserving the values and worldviews of the past from the Chou period was central. Appreciation of the past became a dominant element of Chinese thought under Confucian influence. In this way, according to the sinologist Nakamura, the Classical Scriptures preserved from unbound individual thinking and thus saved the Chinese.

Buddhism

As early as the Han period (206 BC - 220 AD), Buddha's teaching reached China in the 1st century AD by sea and the Silk Road. This religion, which according to the sinologist Kai Vogelsang "should put its stamp on the Chinese Middle Ages", began as a subculture. The 5th / 4th Century BC Doctrine, which originated in the 3rd century BC and which, in contrast to Chinese conceptions, claimed that there was something beyond in contrast to this world, had already undergone some changes on the centuries-long journey to China. The first import involved individual texts and related teachings that were represented by Indian and Central Asian monks. By the end of the 3rd century AD, Buddhist teaching took hold of larger parts of the Chinese population. Buddhism , which originated in India , began to integrate a foreign element into the Chinese culture for the first time. Buddhist teachings were completely transferred into Chinese and - similar to ancient texts by Christian translators - interpreted or Sinised . The translation work was done by Indians, Sogdians, Persians and Central Asians who knew Sanskrit and Chinese. Chinese assistants continued to work on the text.

These translations were also used as graphic and literary products in the various Buddhist-Chinese schools and temples. Some of these were stylized diagrams or aphorisms or reports of events. The differences in content between the adopted and widespread teachings were irrelevant within the Chinese Buddhist schools. Knowledge of Sanskrit was rare among Chinese Buddhists even in the marriage of the Buddhist religion.

The afterlife Buddhist teachings were well received. In contrast to the Confucian and Daoist teachings, they offered clearer ideas about life after death, as well as explanations for personal fate. These ideas appealed not only to the people, but also increasingly to the literary and philosophical educated at court and nobility. By 400 AD there may have been 1,700 monasteries and 80,000 nuns and monks in the Eastern Jin Empire . For several centuries, Buddhism was the predominant religion. It was a social factor and it became a power in the state. The associated political influence became too strong for the imperial family. In 845 AD, Buddhist monasteries were expropriated and monks and nuns were released into the laity. Even if, as the sinologist Volker Häring and his co-author Françoise Hauser wrote in their China Handbook, Buddhism did not recover from this blow, a good ten percent of all Chinese still profess Buddhism today. According to the authors, the number of "occasional Buddhists" is likely to be considerably larger.

For almost two thousand years after Buddhism there were no more similarly strong impulses. The existing schools of Confucianism and Daoism, which at times competed fiercely, were continuously reinterpreted. The efforts of Christian missionaries to establish their religion in the Middle Kingdom, which have been recorded since the 16th century, were unsuccessful and did not gain any lasting influence on Chinese culture.

Culture is experience

Culture can be two things: On the one hand, it is understood to mean particularly valuable achievements by a people or a nation in areas such as literature, language, architecture, music and art. This traditional view is still a common cultural concept in our society. Secondly, there is the concept of culture in the empirical cultural studies, which view culture as the expression of all expressions of life of a people or nation. This “total perspective” is either already taken or required for research into Chinese culture. Culture is viewed as having grown historically, it has produced successes, but it is not rigidly fixed, but changes through joint action. Culture should stimulate the exchange between cultures. To do this, it is essential to reflect on one's own culture and that of others. The question of the value of cultural phenomena is considered after data collection and the accumulated facts, in which their meanings are explored. The conditions of human thinking, feeling and acting should also be made visible. Within the framework of this empirical program, culture is defined in more detail as text culture, as a system of symbolic forms, as performance or ritual, as communication, as everyday practice, as standardizations of thinking and acting, as a mental orientation system or as a totality of values and norms.

Approaches to Chinese culture

Chinese culture is significantly different from western cultures. According to cultural scholars, ideas about Chinese culture in Europe tend to be shaped by impressions of its strangeness. Such impressions - in addition to the language - prevented Chinese cultural phenomena from being understood. Yuxin Chen therefore prefers to speak of 'strangeness profiles' instead of 'China profiles'. Above all, being rooted in one's own culture makes it difficult to understand foreign cultures. It might help to get a deeper understanding of Chinese culture - for example, B. Sinologists - to exchange views on European and Chinese philosophies, because every culture has its own traditional understanding of values.

There are research approaches that aim to overcome ties to one's own culture. An author who devotes herself comprehensively and in detail to the intercultural learning of employees in China mentions the work of the social psychologist and cultural scientist Geert Hofstede and Alexander Thomas

Hofstede developed ideas for “cultural dimensions” as well as key categories that were collected from the social sciences, which he also called values, in order to describe the differences between cultures and to make social structures and actions clear. By using his constructs, it should be possible to understand and approach foreign cultures. From a social-psychological point of view, Thomas developed cultural standards that regulate everyday action and communication. This should enable Europeans to communicate successfully with the Chinese and other peoples. Thomas understands cultural standards as what people of a certain culture have learned in the course of their social development, what they regard as normal and self-evident for themselves and others, act accordingly and judge others according to this norm.

These cultural standards or key categories were obtained on the basis of 'empirically obtained data' from interaction situations and cultural knowledge (historical, philosophical, literary or religious studies sources) and they are shaped by the researchers' own cultural perspective. From the point of view of scientists, they have a structuring value in all changes in order to be able to understand Chinese thinking and behavior. Both Hofstede and Thomas' ideas were and will be implemented in training programs for German employees in China. Both authors seem to assume that the following applies to Chinese culture as to every culture: There is a reasonably stable core of value systems that shape a culture and are difficult to change.

The German public's image of China is not shaped by the results of cultural studies, but by the mass media, as well as the profiles of China in non-fiction and advisory literature. In the reporting of the German press about China, there are no cultural, but political topics. It has been shown over the past 40 years that rapprochement with Western ideas has been followed by positive assessments, while China's insistence on old political structures and independence has provoked negative criticism.

Cultural standards

Characteristics of Chinese culture can be identified in interpersonal relationships. Their general meaning has the character of tendencies or patterns . They were z. B. not at all times and not equally pronounced in all areas of China. In addition, as in other cultures, there are differences between ideals and reality, which can be very pronounced.

From a Western perspective, mindfulness could prove to be the key to understanding Chinese behavior and developing appropriate responses in the following three interpersonal areas:

- Save face ( 面子 , miànzi ).

- Maintain relationships ( 關係 / 关系 , guānxi ).

- Practice “courtesy” ( 禮貌 / 礼貌 , lǐmào ).

The extent to which these characteristics and the characteristics outlined below are reflected in the behavior of the individual, however, is primarily determined by the group membership of those involved

Groupthink and Insider-Outsider Discrimination

Certain sociological theories such as groupthink and insider-outsider discrimination are used to describe central elements of Chinese culture from a western perspective. In connection with empirical data, these theories determine to what extent and in what situations the other cultural characteristics are reflected in social life. The latter can be shown in a multitude of often unmanageable and objectively barely identifiable boundary lines. Based on these theories, social restrictions and possibilities of intercultural communication are discussed.

The distinction between family members ( 家人 , jiārén ) and non-family members ( 非 家人 , fēi jiārén ), which is also common in other cultures, is relatively obvious in China . This is followed by the distinction between “own people” ( 自己人 , zìjǐrén ) and “outsiders” ( 外人 , wàirén - “the outsider, the stranger”). The criteria for differentiating who belongs to which group are very complex. They can range from regional origin, clan affiliation or family name, affiliation to social groups to department affiliation at the workplace or employer or Danwei . For outsiders, these criteria and the exact course of the resulting boundaries between the groups are usually difficult to understand. The outermost and readily comprehensible distinction is between Chinese ( 中國人 / 中国人 , zhōngguórén ) and foreigners ( 外國人 / 外国人 , wàiguórén ). In many cases, a more or less clear distinction is made between Han Chinese ( 漢人 / 汉人 , Hànrén ) and members of other ethnic groups within China.

Your own ideas, expectations and behavior are naturally changed along these lines. In addition, extremely pronounced prejudices or aversions of the members of different groups towards one another (outgroup bias) can be seen at each of the border lines shown. Above all, the need for harmony, which is closely interwoven with Chinese culture, takes a back seat and can even lead to the uncompromising assertion of interests of one's own group (ingroup interests) (e.g. the interests of family members, one's own people or Han Chinese) towards the Lead interests of other groups (outgroup interests) (e.g. the interests of non-family members, outsiders or non-Han Chinese). Within the respective groups, however, striving for harmony and groupthink generally dominate.

harmony

A defining characteristic of the Chinese imagination has always been the idea that the cosmos is in a harmonious equilibrium that must be preserved and restored in the event of threats. It has found classic expression in yin-yang thinking or in the analogy of the five-element theory , according to which certain colors, seasons, moods, materials, planets, body parts correspond to one another and must be coordinated with one another. Later in particular has Taoism focuses on the harmonious relationship between heaven, earth and man comprehensively. A special role in maintaining harmony always played the emperor as "Son of Heaven", in whose Beijing palace not a few buildings even have "Harmony" in their name.

Similarly, harmony in human relationships is also sought. Conflicts are therefore generally perceived as a disturbance and one tries to avoid them as much as possible. Mutual support in the group is therefore valued and employees are encouraged to develop concepts together.

The uncompromising enforcement of one's own interests is considered immoral in China, even and especially when it is based on binding “ law ”, and is sanctioned accordingly. Rather, attempts are usually made in lengthy processes to find a compromise solution that is satisfactory for all parties involved . Of course, against this background, a harsh “no” is also forbidden, which of course often means that a “yes” may not always be regarded as binding. Critical expressions of emotions such as anger, anger, sadness or joy as well as revealing too much information about yourself (with the exception of financial matters) as well as burdening other people with your own problems, worries or problems are also considered harmony disorders Considered intimacies.

Quiet and reserved demeanor, calm to gentle speaking, dignified gestures and composure in the face of annoyances are valued . The latter is particularly expressed in the frequently used phrase Méi yǒu guānxi ( 沒有 關係 / 没有 关系 , wàiguórén - “That has no meaning, that doesn't matter”). In some contexts, such as guest visits, exuberant praise is expected.

As far as loud, inconsiderate behavior by Chinese people can be observed today, this has a particular cause: The duty of harmony only applies without restriction in the area of one's own Danwei community, but not in the wider public. From jostling at the bus stop and recklessness in traffic, therefore, in no way can one infer the behavior of the same person in the family or in the company.

face

In the Chinese culture, face ( 面子 , miànzi or 臉 子 / 脸 子 , li wirdnzi ) is understood to mean not only the physical face , but also the opinions or reputation that others have about a certain person, or the appreciation they have for them becomes. The Chinese traditionally place great value on their faces .

For example, those who “lose face” do not meet the requirements placed on them in their social role, such as father, employee, student, etc. The loss of face is particularly strong when this deficit is also expressly determined by others, for example through criticism , reprimand, exposure, etc. in front of third parties, whereby in these cases the critic usually also loses face. The fear of being ostracized or “laughed at” has been deeply rooted in the Chinese from childhood; In this respect, Oskar Weggel speaks of a Chinese culture of shame , which he contrasts with the Western culture of guilt . Ultimately, this attitude leads to an increased pressure to conform, which in turn intensifies the “ritualization principle” mentioned below. Violations of the above also lead to loss of face. Harmony requirement, for example by showing anger and anger.

Often the fear of losing face prevents the Chinese from taking even the slightest risk and risk. This explains, for example, the reluctance of Chinese hotel employees to (exceptionally) take on tasks on their behalf that have not been expressly assigned to them. Ignoring inquiries that could only be rejected is often associated with the risk of losing face for both sides. One of the worst insults in Chinese is the phrase 不要臉 子 / 不要脸 子 búyào liǎnzi. What can be roughly translated as “being shameless” or “being indecent” literally means “not needing a face ”, ie “having no reputation to lose”.

Indirectness

Illustration for the novel The robbers from Liang-Schan-Moor , 15th century

The principle of harmony, as well as the doctrine of the face, often force a considerable degree of indirectness in communication. You avoid "falling in with the door". “Hot irons” are not dealt with directly, rather the interlocutors move in numerous turns and general remarks towards the actual topic. Central statements are often kept short and on top of that hidden in a less exposed place, for example in subordinate clauses. In this respect, non-verbal communication and the use of parables and symbols also play an important role .

A popular technique is the so-called shadow shooting , in which criticism is formally directed not against the actual addressee, but against another person; it is often referred to as " Pointing at the mulberry tree, the acacia revile ". A classic example of this is the " Anti-Confucius Campaign " of 1974, which was by no means directed against the ancient philosopher, but rather against his prominent contemporary admirer, the politician Zhou Enlai . Also, the drama " The Impeachment of Hai Rui " from the pen of the Deputy Mayor of Beijing, Wu Han , in no way criticized the Ming Emperor Jiajing , but rather the great chairman Mao Zedong himself, who in 1959 removed a "modern" Hai Rui from office had - namely Marshal Peng Dehuai .

But even the technique of shadow shooting is traditionally reserved for influential personalities who are firmly in the saddle. The common citizen has to present any criticism even more subtly and is often limited to describing his own sufferings without explicitly addressing the act of what is indirectly criticized that produces it. Examples can be found in the works of the writers Mao Dun and Ding Ling . In the film " Bitter Love ", the portrayal of a person painting a big question mark in the snow led to a month-long campaign by the CCP against the author and director.

Collectivity

In the thinking of Chinese societies, the community has always been more important than the individual. It is already symptomatic in the Confucian family, but especially in the Danwei ( 單位 / 单位 ), small, manageable collectives that can exist in a village community, a company, a university, an army unit or the like.

Traditionally, the Danwei takes care of all the concerns of its members, but often interferes to a considerable extent in their private affairs. a. include: allocation of home and work, distribution of wages, bonuses and vouchers, provision of local infrastructure, marriage, divorce and school attendance permits, recruitment to the militia service, leisure activities, political training, exercise of censorship, dispute settlement, minor judicial tasks. Despite all the control, the Danwei also offers the individual a certain amount of democracy , participation and codetermination, from which he is excluded in the so-called Trans-Danwei area, i.e. at the national level.

Membership in Danwei is lifelong, a change to another Danwei is not normally provided. The Danwei also expects unconditional loyalty and solidarity from its members . Significantly, the Confucian moral duties only apply to their full extent in the Danwei, but not in the Transdanwei area - which can lead, for example, to the fact that one is relatively reserved and indifferent to the suffering and misfortune of non-Danwei people and certainly does not intervene to help.

The Danwei character is still very pronounced in the country today. In the cities, however, a split took place a long time ago in that the individual belongs to both a residential and a workdanwei with different tasks. After the importance of the Danweis under Maoism had reached a historical climax, a decline has been recorded since the beginning of the 1980s in the course of economic reform policy.

The collective thinking, which is deeply rooted in the Danwei being, means that the Chinese still prefer community activities to individual activities. Work, life and leisure activities are largely carried out in the group. Loners and individualists are traditionally little appreciated. Accordingly, “privacy” is of less importance in China than in the West. At least within one's own Danweis, unannounced visits or, from the western point of view, “intrusive” questions are definitely accepted.

Hierarchical awareness

Confucius had already divided human relationships into asymmetrical superordinate / subordinate relationships such as father / son, husband / wife, master / servant, master / student and developed a complex hierarchical structure on this basis . Even in the imperial family, a strict distinction was made between the ranks of the various wives, concubines, concubines and princes. After her came the officials, divided into 18 ranks, followed by the farmers, the various trades, and then the merchants, who were differentiated according to their merchandise. Even among the socially declassified at the lower end of the scale, whores, for example, were ranked higher than actors. Even within the sibling rows of a family, the brothers were sorted by age, for example, and the sisters came after them. The lower owed obedience , respect and support to the higher placed , while the latter owed protection and instruction.

Even today, hierarchical awareness is deeply anchored in the minds of most Chinese. Within a Danweis, each member has a fixed position and rank, which is to be respected equally by internal and external persons. In many cases it is secured by meticulously monitored status symbols such as the size of the office, desk or company car. At conferences, it is reflected in the seating arrangement: At long tables, for example, the heads of delegation sit in the middle, with the 2nd on their right and the 3rd on their left. Changes to the external seating, standing or marching order are inevitably interpreted by the Chinese as shifts in the power structure. When, for example, at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, Liu Shaoqi no longer came through the door as second behind Mao as before, but only as seventh, this was generally considered a political death sentence. Subordinate members have to participate in the negotiation only with the express permission of the head of delegation. You may not be approached directly by the other side, but only in strict compliance with official channels. Gifts distributed to the delegation members have to reflect their differences in rank in their value.

The principle of hierarchy was turned into the complete opposite during the Cultural Revolution . Lower-ranking Chinese were expressly urged to, often even pushed, to rebel against the traditional authorities. An extreme example are the students who banded together to form “red guards” in order to mock, humiliate or even beat up their teachers. Even if these conditions did not last, they can still be observed in today's hooligan literature , works by young Chinese who defy all authority.

Ritualization

Another basic feature of Chinese culture is ritualization. Many actions and processes in daily life are or were subject to strict regulations that must be observed. They are mostly given by tradition and thus ultimately by the ancestors or the master, which closes the circle to the hierarchy already mentioned. The high regard for learning is just as much a part of this as the bureaucracy that has always been strong in China .

Deviations from the requirements are at best ridiculed, but often sanctioned. In this respect, spontaneity, improvisation, originality or self-fulfillment are largely frowned upon, which, together with the fear of losing face, leads to increased pressure to conform and the low prevalence of eccentrics in China. Against this background, copying of role models is expressly seen as desirable, praiseworthy and in no way reprehensible, which contributes to the explanation of the product piracy that is flourishing in China today .

Examples of ritualization are the various traditional greetings and bows, which had to be precisely aligned with the status of the person opposite, the way in which food is served, tea is poured or business cards are handed over. When writing their characters, the Chinese usually make sure that the lines are drawn exactly in the prescribed order, even if this can no longer be determined or understood from the “end product”. Even at the imperial official exams , the candidates were expected to have meticulous knowledge and reproduction of the Confucian classics. As a pious Confucian son, one had to mourn for exactly three years after the death of his father - regardless of the actual mood.

In many cases this has been used to explain the astonishingly static character of the Chinese community over the centuries. Indeed, paintings or stories from the Qing dynasty are often stylistically indistinguishable from their models from the Tang period ; the same applies to philosophical or political ideas: at the latest from the turn of the ages, the classical teachings of the Axial Age , i.e. Confucianism , Daoism and legalism, were only reinterpreted; however, due to the “admiration” of the ancients, nothing groundbreaking was added. In the middle of the 19th century, the resulting “rigidity” was supposed to contribute to China's relapse towards the West and thus to the decline of the empire and its fall into semi-colonial dependence.

This-sidedness

Another characteristic of Chinese culture is its strong focus on this world. This is most pronounced in Confucianism: There questions such as the structure and origin of the cosmos , the fate of the human soul or the entire topic of sin and redemption were never in the foreground from the start; rather, the master has mainly dealt with human coexistence according to the principles of morality ( 禮 / 礼 , Lǐ ).

In general, therefore, the wishes of the Chinese are not directed towards a “better life after death”, but rather towards the longest possible life. The Confucians regard death as a negative turning point, which explains the extremely long mourning period of three years. The traditionally strong ancestor cult serves primarily to ward off the threats threatening the soul of the deceased in the afterlife, the consequences of which can in extreme cases fall back on the bereaved.

Given the negative assessment of death, longevity ( 壽 / 寿 , Shòu ) has traditionally been a central goal for the Chinese; There are hardly any other terms in China that have so many symbols (including crane, deer, pine, peach, and many others). The increase in this is immortality ( 不朽 , bùxiǔ ), which was particularly sought by the Daoists .

But also for the time of life itself material desires are mostly in the foreground, u. a. for example happiness ( 福 , Fú ), wealth ( 富 , Fù ), a lucrative position ( 祿 / 禄 , Lù ) and sons ( 兒子 / 儿子 , Érzi ). So you wish each other "ten thousand times happiness" ( 萬福 / 万福 , Wànfú ), give yourself calligraphy with the sign "Long Life", or pray to the "God of Wealth", who can be found in every village temple. Whilst in the Qing period whole novels dealt with the acquisition of the rank of civil servant by a young man, the lucrative job at a transnational company has taken its place for today's aspiring Chinese youth. The traditional Chinese appreciation for good food and demonstrative consumption also belong in this context.

Metaphysical elements emerge more clearly in Daoism and Chinese Buddhism . Here, too, over time, popular variants that are more oriented towards this world have developed: For example, the Daoist deities are often bothered with extremely earthly desires such as wealth or the blessing of children. Even the heavenly court around the Jade Emperor reflects the real conditions in the Chinese empire in great detail. The variant of Buddhism prevailing in China, the Mahayana school, provides - unlike the Indian original form Hinayana - the possibility of a substitute redemption of humans through Bodhisattvas (in particular the widely revered Guanyin and Buddha Amitabha ), whereby the individual has a considerably lower level spiritual maturity that can only be achieved through asceticism and meditation is required and a stronger turn to earthly life is made possible. In Chan Buddhism , too, elements of this world are relatively strong.

Sinocentrism

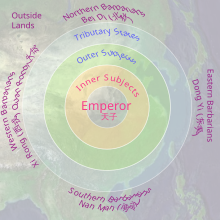

At the latest since the unification of the empire by the first emperor Shi Huangdi in the 3rd century BC. China felt itself to be the center of the world and - regarded as "barbarians" - other peoples. This is already exemplified in the self-designation Zhōngguó ( 中國 / 中国 ), which is translated as "Middle Kingdom". The origins of this thinking are cosmological notions, according to which the world is a geometrically structured disk, at the center of which is China, the imperial palace and finally the emperor himself, who as the "son of heaven" has a special mandate . He saw himself as the ruler of the whole world and had the task of regulating and governing this world in the sense of "heaven". It was thought of civilization and a peaceful order.

Accordingly, over the centuries, more and more nomadic neighboring peoples became tribute states until China finally under Emperor Qianlong in the 18th century reached an area of around twelve million square kilometers and stretched from Siberia to the Himalayas . Other countries like Korea or Vietnam became vassal states. "The experiences and adaptations (adjustments) from these often warlike, but mostly cooperative relationships formed an important prerequisite for the expansion and stability of the later imperial era ..."

According to his "heavenly mandate", the emperor never dealt with foreign rulers on the same level; instead, tribute payments were required for the protective power of China and, as an outward sign of respect, consistently repeated kowtows . The request of the English King George III. the establishment of equal diplomatic relations in 1793 therefore met with incomprehension and resistance. It was not until the defeat in the First Opium War that the ruling Chinese emperor was forced to conclude a treaty with Great Britain, which the British regarded as a partnership, but which the Chinese described as an unequal treaty .

The entire Chinese sphere of power was consequently "sinized", that is, adapted to its own culture. Conversely, the Han Chinese even succeeded twice in Sinizing cultures of indigenous ethnic minorities who had gained power in all of China, namely the Mongols in the Yuan and Manchurians in the Qing Dynasty . As far as foreign teachings were imported, these were sometimes so consistently sinised that in the end they had little in common with their model. Examples of this are Buddhism and, more recently, communism .

Traditionally, people in China were convinced that everything useful and desirable had been discovered or invented in their own country and that there was no need for foreign goods and ideas. Accordingly, in 1793 , Emperor Qianlong harshly rejected the goods offered by the Macartney Mission's emissaries . Insofar as culture and technology imports were allowed, for example during the culturally open Tang dynasty or later by the European missionaries , the history of science was often confused with confusion: a scholar was quickly found who proved that astrolabes and seismographs were already there previously invented by the Chinese, but were then forgotten.

The Sinocentric principle experienced a considerable collapse when China, humiliated after the First Opium War , fell into a status of semi-colonial dependence. It has recently experienced a certain renaissance, as China is about to move back to the top of the nation, not least due to impressive economic growth.

China in comparative cultural research

In the GLOBE study , 61 cultures were compared with one another. In a global comparison, China stood out for its high scores in the areas of performance orientation , avoidance of uncertainty and collectivism . On the other hand, the future orientation was low in an international comparison. The study has confirmed some of the results that the cultural scientist Geert Hofstede had already worked out with his large-scale survey in global offices of IBM (1967–1973).

Forms of expression

The aforementioned characteristics of Chinese culture are expressed in many ways in everyday life as well as in politics, art and other areas of human existence. Since even an overview would go beyond the scope of this article, reference is made to the relevant specialist articles, in particular

- Chinese Art , Chinese Painting , Chinese Calligraphy , Chinese Porcelain , Chinese Lacquer Art , Chinese Wallpaper

- Chinese architecture , Chinese garden art

- Chinese literature

- Chinese music , Chinese opera , Chinese puppet theater , Chinese shadow theater

- Chinese Philosophy , Confucianism , Neoconfucianism , Daoism , Buddhism in China , Legalism , Chinese Folk Faith , Chinese Mythology

- Chinese language , Chinese writing , Chinese symbols

- Traditional Chinese medicine

- Chinese cuisine , Chinese tea ceremony

- Chinese martial arts

- Mui Tsai

- Park dance

See also

- Chinese Folk Literature and Arts Society

- List of museums in the People's Republic of China

- Education in China

literature

- Xuewu Gu : cunning and politics. In: Harro Senger (Ed.): Die List. Frankfurt 1999, p. 424 ff., ISBN 3-518-12039-5

- Françoise Hauser (Ed.): Journey to China - a cultural compass for hand luggage. Unionsverlag, Zurich 2009 ISBN 978-3-293-20438-6

- Jean-Baptiste Du Halde: Description geographique, historique, chronologique, politique et physique de l'empire de la Chine et de la Tartarie chinoise, enrichie des cartes générales et particulieres de ces pays, de la carte générale et des cartes particulieres du Thibet, & de la Corée; & ornée d'un grand nombre de figures & de vignettes gravées en tailledouce. New edition, Henri Scheuerle, The Hague 1736. on archive .org

- Jean-Baptiste Du Halde : Detailed description of the Chinese Empire and the great Tartarey , Vols. 1, 3, 4, ISBN 978-3-941919-14-3 , pp. 22–28, 33 f., Rostock 1747–1749.

- Linhart Ladstätter: China and Japan; The cultures of East Asia. Carl Ueberreuter, Vienna 1983

- Hajime Nakamura: Ways of Thinking of Eastern Peoples. India-China-Tibet-Japan . University of Hawaii Press (Paperback edition) USA 1968. engl. Full text archive.org

- Jonas Polfuß: "Intercultural Conflicts and Solutions: Examples from German-Chinese Practice" (PDF; 1.4 MB) In: Magazine of the Chinese Industry and Trade Association , issue 19, February 2013, pp. 27–30

- Dominik Schirmer: Lifestyle research in the People's Republic of China . Dissertation Bielefeld 2004.

- Oskar Weggel: The Asians. Frankfurt 1997, ISBN 3-423-36029-1

- Oskar Weggel: China. Munich 1994, ISBN 3-406-38196-0

- Martin Woesler: China's contemporary culture. Underground culture and dialogue. Bochum 2004.6, ISBN 978-3-89966-038-8 , 52 pages, Scripta Sinica series 20

- Martin Woesler: Phenomenon, Clash of Civilizations 'and Trend, World Culture'. Cultural identity, cultural relativism. “The Other”, racism, national pride, prejudice, integration. Bochum ²2005, ISBN 978-3-89966-147-7 , 58 pages, Scripta Sinica series 29

Web links

- Various articles about individual phenomena of Chinese culture (English)

- Michael Lackner: Is a generic term “Chinese culture” necessary to understand politics, economy, society and culture of contemporary China? In: bpb.de , July 13, 2005.

- Article on Chinese mentality and psychology of Chinese culture ( February 5, 2010 memento on the Internet Archive ) (archived version of February 5, 2010)

Individual evidence

- ↑ See Anne Löchte: Johann Gottfried Herder . Würzburg 2005. P. 29. - Also Klaus P. Hansen (Ed.): Concept of culture and method: the silent paradigm shift in the humanities . Tübingen 1993, p. 172.

- ^ Website of the Chinese Embassy in Berlin

- ↑ The Chinese expect answers to life's questions from philosophy and world views. They didn't develop systems like the Europeans.

- ↑ See Hauser / Häring: China-Handbuch. Berlin 2005, p. 11f.

- ↑ See Helwig Schmidt-Glintzer: The new China: From the Opium Wars to today . 5th edition. Munich 2009, p. 8.

- ↑ Helwig Schmidt-Glintzer: Small history of China . Munich 2008, p. 11 f.

- ↑ See Hauser / Häring: China-Handbuch. Berlin 2005, p. 16.

- ↑ See China in Focus: Title text

- ↑ Cf. Helwig Schmidt-Glintzer: Little History of China . Munich 2008, p. 15.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Bauer : History of Chinese Philosophy . Munich 2006, pp. 25-29.

- ^ Hellmut Wilhelm : Society and State in China . Hamburg 1960, pp. 90f.

- ^ Feng Youlan: A short history of Chinese philosophy. New York 1966, 30th edition, p. 21.

- ↑ Cf. Helwig Schmidt-Glintzer: Little History of China . Munich 2008, p. 12.

- ^ Walter Böttger: Culture in ancient China . Leipzig / Jena / Berlin 1987, pp. 188f; 195f.

- ↑ Helwig Schmidt-Glintzer: Small history of China . Munich 2008, p. 26f.

- ↑ Cf. Livia Kohn: Early Chinese Mysticism: Philosophy and Soteriology in the Taoist Tradition . New Jersey 1992, pp. 81–83.- For shamanism and the ritual evocations of spirits, see also Wolfgang Bauer: History of Chinese Philosophy . Munich 2006, pp. 40–43.

- ↑ Cf. Helwig Schmidt-Glintzer: Little History of China . Munich 2008, pp. 27-29.

- ^ Subject of the book Spring and Autumn by Lü Buwei

- ↑ a b Cf. Feng Youlan: A short history of Chinese philosophy. New York 1966, 30th edition, p. 22.

- ↑ Nakamura 1968, p. 212.

- ↑ Helwig Schmidt-Glintzer: Small history of China . Munich 2008, p. 41.

- ↑ See Dai Shifeng / Cheng Ming: History . Peking 1984, p. 15.

- ↑ See Nakamura 1968, p. 213.

- ↑ See Kai Vogelsang: Brief History of China . Stuttgart 2014, p. 134f.

- ↑ Cf. Helwig Schmidt-Glintzer : Little History of China . Munich 2008, pp. 62–69. Also: Michael Friedrich (Hamburg): The Sinization of Buddhism . Lecture digitalization at the University of Hamburg

- ↑ See Hajime Nakamura: Ways of Thinking of Eastern Peoples. India-China-Tibet-Japan . Hawaii Press, USA 1968. pp. 175f; 220-230.

- ↑ See Kai Vogelsang: Brief History of China . Stuttgart 2014, p. 138.

- ↑ See Hauser / Häring: China-Handbuch. Berlin 2005, pp. 62-64.

- ↑ Cf. Vera Boetzinger: " Becoming a Chinese for the Chinese": the German Protestant women's mission in China 1842–1952. Stuttgart 2004, pp. 87-85.

- ↑ Empirical cultural studies at the University of Munich

- ↑ See Yuxin Chen: The Foreign China. Xenological and cultural theory critique of the German-language discourse on China and Chinese culture between 1949 and 2005. Hamburg 2009, pp. 207-9.

- ↑ Cf. Andreas Reckwitz: The contingency perspective of “culture”. Concepts of culture, cultural theories and the cultural studies research program . In: Jaeger u. Rüsen (Ed.) Handbuch der Kulturwissenschaften 2004 , pp. 1–20.

- ↑ See Federal Agency for Political Education. BPB

- ↑ Yuxin Chen: The Foreign China. Xenological and cultural theory criticism of the German-language discourse on China and Chinese culture between 1949 and 2005. Hamburg 2009, p. 8.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Stephan Schmidt: The challenge of the foreign. Intercultural Hermeneutics and Confucian Thinking . Diss. Darmstadt 2005. Quoted by Chen, ibid. Pp. 208 f.

- ^ See Geert Hofstede: Culture's Consequences . London 1980.

- ↑ Cf. Alexander Thomas: Culture, Culture Dimensions and Culture Standards . In Petia GenkovaTobiasringenFrederick TL Leong (Hrgs): Handbuch Stress und Kultur . Wiesbaden 2013, pp. 41–58.

- ↑ More details e.g. B. from the Institute for Intercultural Competence and Didactics Geert Hofstede Cultural Dimensions

- ↑ Steffi Robak: Cultural Formations of Learning. Habil. Münster 2012 , p. 63 f.

- ↑ Robak, ibid. P. 75.

- ↑ Robak, ibid. P. 17.

- ↑ More details e.g. B. from the Institute for Intercultural Competence and Didactics eV Cultural Standards - Alexander Thomas

- ↑ See Robak, ibid. Pp. 64f, 76 and 81.

- ↑ Yuxin Chen: The Foreign China. Xenological and cultural theory critique of the German-language discourse on China and Chinese culture between 1949 and 2005 . Hamburg 2009, pp. 27-29.

- ↑ See Steffi Robak: Cultural Formations of Learning . Habil. Münster 2012, pp. 77–80.

- ↑ See Jonas Polfuß: German-Chinese Knigge . Berlin 2015, p. 31.

- ↑ Concrete information: What behavior Europeans have to expect in China A report on Chinese behavior in the magazine Focus.

- ↑ In line with the appreciation of this hierarchical relationship, Menzius therefore advised: A young person should serve his parents and brothers at home and his prince and superior in public life. Because these are the most sacred relationships between people, added Gongsun Chou. Compare Shaoping Gan: The Chinese Philosophy . Darmstadt 1997, pp. 59-61.

- ↑ On the Confucian patterns in contemporary Chinese behavior: e.g. B. Michael Harris Bond: The psychology of the Chinese people . Oxford University Press 1986, pp. 214-227.

- ↑ See Daniel Leese: The Chinese Cultural Revolution. Munich 2016, pp. 39–42 (uproar at the universities).

- ↑ See Joseph R. Levenson: T'ien-hsia and Kuo and the “Transvaluation of Values” . In: Far Eastern Quarterly, No. 11 (1952), pp. 447-451.

- ↑ Helwig Schmidt-Glintzer : Small history of China . Munich 2008. p. 48.

- ↑ Cf. Hang Xu: The Chinese bankruptcy law: legal historical and comparative studies . Münster 2013, p. 43f.

- ↑ Cf. Günter Schubert: Chinas Kampf um die Nation . Announcements from the Institute for Asian Studies Hamburg 2002, p. 258ff.

- ↑ House, Hanges, Javidan & Gupta (eds.): Cultures, Leadership and Organizations: A 62 Nation GLOBE Study. Thousand Oaks, California 2004