Chinese philosophy

Chinese philosophy describes the philosophical thinking in China since about the time of the Zhou dynasty . Due to its influence on the East Asian cultural area of China , Japan , Korea and Taiwan , it has a comparable position within the framework of Eastern philosophy as the ancient Greek philosophy within the framework of European thought. In the diversity of Chinese philosophies, the philosophical discourse at the present time is determined by currents of the traditional main directions of Taoism and Confucianism in connection with Marxist theories and problems of new social and political situations.

Main features

In today's China, "philosophy" is reproduced using the foreign word Zhexue , introduced in Japanese . It is translated as wisdom in the west . For the Chinese, Zhexue contains a change in the meaning of the attribute 'wise' ( zhe ). This could be described as 'intentional', 'calculating'. It is a quality that is alien to the Chinese concept of a sage.

Another word that is assigned to the foreign word philosophy is sixiang , which describes the activities, 'have ideas / thoughts', 'think', 'consider'. Mao's thinking was z. B. denoted by sixiang . A number of modern Chinese philosophers have suggested traditional terms for philosophy: e.g. B. Daoshu "art of the way", Xuanxue "teaching of the dark" or Lixue "teaching of the principle". However, none of these expressions can be generalized to all philosophical movements.

Fundamental to the Chinese philosophy is the experience that life is subject to 'changes' or 'changes'. The oldest basic book is the I Ching : "The Book of Changes". For the Chinese, change is the starting point for thinking and acting. In contrast, since the end of antiquity, thinking and acting have been fixated on truth and security in western philosophy .

The basic Chinese idea of “changes” has not produced a history of philosophical systems . On the other hand, a story and stories of outstanding personalities and their teachings on how to think and live with this fact. Philosophy was seen as a kind of " mastery ". This is also reflected in the use of the term "Master", which as appendages zi named added that person as a thinking and life practically determined standout.

In an early history, the "historical records" ( Shihi ), the common theme of the first schools of philosophy was named "a single force of motion ". This creates "a hundred thoughts and plans". They all have the same goal and just use different paths ( methods ).

“ The Yinyang scholars, the Confucians, the Mohists, the logicians, the legalists and the Daoists, they all fight for good government [of the world]. The only difference is that they follow and teach different ways and that they are more or less profound. "

Framework conditions for Chinese philosophizing

From the perspective of the philosopher Feng Youlan

Chinese philosophy is an expression of “systematic reflection on life”, said Feng Youlan in his short “History of Chinese Philosophy”. Geographical and economic conditions were part of a thinker's life. These conditions influenced his attitude towards life and therefore lead to certain focal points, but also to defects. Chinese philosophers have lived in a continental country for centuries. Until the end of the 14th century, their world was limited by sea and sky. The term “world” is therefore translated in Chinese by the two expressions “everything under heaven” or “everything within the four seas”. For a people who, like the Greeks, lived in a maritime country, it would be inconceivable that these two expressions should be synonymous, says Youlan.

On the one hand, the economic conditions are of an agricultural nature. The prosperity of the people depends on the farmers or on agriculture. It is important in both peacetime and wartime because it produces the food for everyone. The dealers who exchanged products were also part of the economy. For a Chinese thinker, those who took care of the production of food were and are the second most important group in the social hierarchy. In the first place stood the landlords, who were usually considered scholars because they were educated. In third place were the artists and in last place the dealers.

In the metaphor-rich Chinese language, farmers are assigned to the "roots" area and traders to the "branches" area. Chinese philosophers were and still strive to develop theories that use “roots”. The "branches" tend to be neglected.

Peasants and landlords or scholars are closely linked. Both happiness in life depend on successful agriculture. The farmers benefit from the knowledge of their landlords and from their thoughts, which, put into words, express what the farmers feel. What was put into words shaped Chinese philosophy, literature and art.

From the point of view of the sinologist Wolfgang Bauer

The sinologist Wolfgang Bauer confirmed in his "History of Chinese Philosophy" that the "emphatically continental situation" of China can be seen in "connection" with the basic requirements of Chinese philosophy. He admitted that “certain interests and values” were predetermined by the geographical and social environment. First of all, attention to the cycle of nature. The appreciation of patience, the “ability to wait”. According to Bauer, there is indeed a tendency in Chinese philosophy towards “cyclical ideas” with no beginning or end.

Critically - with reference to Youlan - he pointed out that fundamental objections to Chinese philosophical histories are appropriate from a Marxist point of view. Youlan wrote his history of Chinese philosophy (the short version of which is used here as a source) in the 1930s - at that time still under the influence of positivist thinking that he had got to know while studying in the West, which he had to revise in the Marxist era. Bauer claimed that the peculiarities of Chinese culture and philosophy were obscured by Marxist views. There were actually "some basic moments in the geographical and social environment" that helped shape Chinese problem solutions. “They are, however, very general, so you can only cite them with caution as motifs.” In addition, they have been invoked so often that you don't want to dwell on them, Bauer concluded his comment.

An overview of eras and trends

Beginnings of philosophizing

Origins (since 10th century BC)

The origins of Chinese philosophy go back to around 1000 BC. At this time the I Ching (Yijing), the book of changes, was written . It is one of the oldest literary works in the Chinese language and was later understood as a source of cosmological and philosophical thoughts, especially through connection with the (much later developed) yin-yang doctrine: The basic idea is that all existence is derived from the lawful change the basic forces Yin and Yang emerge. The individual states of this change are symbolized by 8 by 8 hexagrams .

These hexagrams go back to the practice of oracle consultation , which was used for the 2nd millennium BC. Is documented for China. In ancient times, according to the I Ching, “the holy sages” invented the yarrow oracle - the legendary prehistory of China names the great emperor Fu Xi as the inventor - in order to obtain clarity about the order of the world and human fate and to advise the rulers. A number of stalks were pulled out of a bundle of long yarrow stalks. They were put in a heap of long and short sections according to certain numerical proportions in front of the person who was to consult the oracle. According to a counting method invented by the wise men, the set of these sections was then divided up until a six-step character remained. 64 of these characters are recorded in the I Ching, which made predictions for certain situations possible through repeated numerically determined separation. The predictions thematized a dynamic process that arose through the changes in the signs. These images became templates for statements about possible action in the situation they indicated. These were tried out and were an occasion to learn.

Over time, interpretations in the form of sayings were added to these characters, which were collected in writing. Around the year 1000, King Wen of the Western Zhou Dynasty is said to have supplemented this first collection with clear advice on correct action. The original divination manual became a first book of wisdom with instructions on how to act. Laozi was inspired to his thoughts by this book of wisdom. Further additions followed in the centuries that followed, including commentaries by Confucius and other philosophers of the classical period. The book, annotated and published by Confucius, forms the basis of today's editions.

The “Book of Changes” or the “I Ching” is the basis of all Chinese philosophical directions. To this day it documents a “generally binding world plan” for philosophers. This world design emphasizes the idea of the “unity of heaven and man” and focuses on the Tao of heaven as the power of life and fate. Man must follow the Tao if he is to maintain unity with it. No Chinese philosopher has ever questioned this unity. Freedom or self-determination of the individual in the western sense were not the basis for action. The rules of life for the individual emerged from research into the Tao. The philosophers, especially those of Confucianism and Taoism, had the task of empowering people, with the help of the realities of life and fate to be explored by them, to lead the most fulfilling and humane life possible, which included needs here and there.

Classical period (6th - 3rd century BC)

Classical Chinese philosophy took hold in the period of the Hundred Schools from 771 BC. Until the beginning of the Qin Dynasty 221 BC. Chr. Shape. Since the 11th century BC The ruling Zhou dynasty had lost its unifying power and ruled only nominally. In fact there were a number of individual states. Their princes (feudal lords) waged wars against each other for rule over China. China's cultural area began to expand from the northern cultural area to the south and west. In this chaos, traditional rules, regulations and rites were overridden and the previously applicable morals were ignored. In this chaos, China's classical philosophy emerged. There were a hundred (very many) quarreling schools of philosophy. From this multitude of competing philosophical drafts, two main philosophical currents emerged: the school of Confucius and Laozi . The "unity between heaven and man" valid in the I Ching was the common worldview of their philosophizing.

Both schools dealt with the question of a consciously led and successful life in family, society and the state; in the interest of the personal needs of the individual, also with the question of withdrawal and distance from the prevailing norms and constraints. Taoism showed an urge for higher knowledge (spirituality), which competes with the natural urge and in the extreme consequence meant renouncing participation in the life of the community. In Confucianism - always with a view to the sky - the focus is on the training of natural abilities, the acquisition of knowledge and the development of morality in order to participate and collaborate in the community in the best possible way.

One can therefore say: Confucianism is oriented on this side, Taoism oriented on the other side. But one cannot say of any person that he is only oriented on this side or only oriented on the other side. Each individual is part of the universe according to the “unity of heaven and man”. The classical philosopher Hui Shi (370-310 BC) called it the "Big One", beyond which there is nothing.

In view of the fact that everyone is part of the whole, Taoists and Confucianists from the beginning focused on developing the ability to think. It is the task of the philosophers to guide people to be able to touch this unspeakable one, the Tao, in a thinking way. The unconventional way of speaking and representation of Chinese philosophers in aphorisms, sayings and illustrative examples served this guide.

The schools of thought of the Classical Age

According to traditional historiography, the legendary 100 schools of the Warring States' era developed into 6 schools that characterize different currents of Chinese philosophy. The term "school" means private associations.

- The Ju school, whose members came from the writers .

- The Mohist School, whose members came from the knights .

- The Taoist school, whose members came from the hermits .

- The school of names whose members came from the debaters .

- The Yin-Yang school, whose members came from practitioners of the occult arts .

- The School of Legalists, whose members came from the Men of Methods .

The teachers in these fraternities were experts in various fields of science and art. Ju teachers were experts in teaching the classics and the practice of ceremonies and music, e.g. B. Confucius. There were experts in warfare. They were the hsieh or knights, e.g. B. Mozi. There were experts in the art of speaking who were known as the pien-che, or debaters. There were experts in magic, fortune telling, astrology, and number mysticism known as the Fang-shih, or practitioners of the occult arts. There were also experienced politicians who could act as private advisers to feudal rulers and who were known as fang-shu chih or "men of methods". Among them were men who condensed their methods into theoretical concepts of governance. These concepts were later used by the legalists. Finally, there were some men who were well educated and talented but so embittered by the political chaos of their time that they withdrew from society and into nature. z. B. Laozi. These were known as the yin-che or hermits or hermits.

Confucius

The classical period begins in the 6th century BC. With Confucius (551–479 BC). Philosophically it was about the establishment of peace orders in the broadest sense. Confucius claimed that these peace orders were only possible through self-restraint and a return to the rites and customs of the Zhou period .

Behind this conservative attitude is the view that people and forms of society are links in a chain of generations before and after. What generations before the present have devised and practiced is a treasure that the present should use for itself. The criterion for which traditional content and practices should be adopted results from the currently valid morality. It was the job of the philosophers to develop standards for this morality in view of proven principles. This resulted in philosophical models based on the values of the family system, ancestor worship and centuries-old cosmological ideas.

Confucius' moral beliefs have been passed down by some of his students in the form of conversations and anecdotes. As in the Zhou period, the concept of heaven is at the center of his thinking. Heaven ( Tian ) is an impersonal being for him, although it occasionally bears anthropomorphic features. The rulers of this time were considered representatives of heaven. Heaven makes absolute moral demands on man, which include the duties and virtues of both rulers and subjects. Morality has a metaphysical basis for Confucius insofar as he assumes that it is the expression of an unchangeable universal law that regulates the course of history in a manner corresponding to cosmic harmony.

Confucian ethics are based on the idea that man is naturally good and that all evil about him is due to a lack of insight. The goal of education is therefore to impart the correct knowledge. The best way to do this is to study history. The great figures of the past provide the models that one can emulate. Respect for parents is the first duty. But beyond the family there is also an obligation to the earth as a whole.

According to Confucius, social life is governed by the five relationships ( Chinese 五 倫 / 五 伦 , Pinyin wǔlún ): father - son, husband - wife, older brother - younger brother, prince - subject, friend - friend. These relationships result in different obligations.

As a practical guideline for action, Confucius recommends the golden rule “What you do not wish for yourself, do not do to others.” Justice has its limit when it comes into conflict with piety . So z. B. the son does not report the father if the father has stolen a sheep:

- The Prince of Schê spoke to Master Kung and said: “In our country there are honest people. If someone's father has stolen a sheep, the son bears testimony (against him) ”. Master Kung said: “In our country, the honest are different. The father covers the son and the son covers the father. That is also where honesty lies ”.

The moral ideal is represented by the “noble” person. His task is to raise the whole of the people to a higher moral level. His behavior is characterized by courtesy in dealing, deference to the authorities, and caring for the people. He is righteous and only cares about the truth, not about himself.

Laozi

The second major figure of the classical epoch is Laozi (between 6th and 3rd centuries BC). Apart from a legend in Sima Qian (approx. 145–86 BC), his life is in whom he appears as an older contemporary and teacher of Confucius, little known. The work ascribed to him, the Daodejing , often simply referred to as “Laozi”, is the basic register of Daoism alongside the Zhuangzi . It is the most widely translated work in the Far East. In terms of its importance for the Asian region, it is equivalent to the works of Plato for Western philosophy.

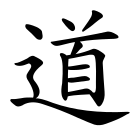

The book ( Jing ) deals with world law ( Dao , Chinese 道 , Pinyin dào ) and its work ( De , Chinese 德 , Pinyin dé ). The Dao is "the constant, true path", "a path without a path, a path that arises under one's own feet by walking it". In order to go this way and to be able to participate in the Dao , the De is required . According to the Daodejing, a person who has De does not shine in the eyes of his fellow men, but he has an extremely beneficial effect on them. He does no harm to anyone, he practices kindness towards friends and enemies, he doesn't ask anything for himself, but by not doing it promotes the beneficial course of all things. He is a role model to the seeker, not an obstacle to worldly people. The Dao is characterized by simplicity, wordlessness, spontaneity and naturalness. It follows its own nature ( Chinese 自然 / 自然 , Pinyin zìran ) and is a "doing without doing" ( Wu Wei , Chinese 無爲 / 无为 , Pinyin wúwéi ).

Following the example of the Dao , the action of the wise is also non-action ( Wu Wei ). This does not mean just doing nothing, but doing something naturally, without unnecessarily interfering with the course of things: “Practice not acting: this is how everything will be okay”.

On this point, Laozi's ethics differ significantly from those of Confucius. It emphasizes the importance of a life in harmony with nature, while the area of culture takes a backseat.

Mozi

The third of the great school founders of the classical period Mozi (? 497–381 BC) lived not much later than Confucius. In contrast to Confucius, Mozi believed in the existence of a personal God and in the continued existence of people as spirits after death. He probably came from the class of "knights". During the centuries of wars , many of them wandered through the domains of the warring states in search of employment. They were therefore called the "traveling knights" ( 'hsie' ).

In one of the northern states, probably in Lu , some formed a group under Mozi. While he was moving from one chieftain to another, Mozi offered himself, his knowledge and his followers as advisors and supporters in defense against impending attacks. This group and their successors went down in philosophy history as Mohists because Mozi had developed his own philosophy . With the help of logic, he wanted to enforce an “overriding political principle”.

His political theory “... is an implementation of the professional ethos of the 'errant knights', which is based on obedience and discipline. It undoubtedly also reflects the turmoil in the political conditions in Mozi's day, which made many people want a central power, even if it were despotic. "

With a logical-rational elaboration of the ethics of the knights, he developed the moral framework for this . He provided it with a reasonable and justifiable justification and developed it under the designation "all-encompassing love" ( jian ai ) to a generally valid principle for all human states in the world. Instead of family ties, general human love is the basis of the state constitution.

He replaced the meaning of heaven, which seemed abstract to Confucius, with the belief in an all-controlling God, which was binding on everyone, and thus met religious needs. It is indispensable for the good of all to promote this belief, which has been present among the people since the mythical time of the wise emperors . Rulers and superiors determine what is right and wrong. Violations of any kind are punished either by heaven or by God and the spirits of the ancestors or by state institutions.

Western sinologists and missionaries have in the past associated echoes of Christian charity with the principle of all-embracing love, but love does not have the ethical value for Chinese thinking that corresponds to Christianity. It is above all feeling and passion ( qíng ), as it is e.g. B. is depicted in Chinese poetry and traditional Chinese opera . The Chinese word ai for love in the translation "all-encompassing love" primarily refers to the institution of marriage . Mozi regards this duty-filled love as a useful and irreplaceable basis for the functioning of states. In his theory, it is an example of behavior that focuses on the benefits that one has from one another.

The legalists

This philosophical current, like that of Mohism, arose in the time of the "Warring States". Shaoping Gan calls legalism a "remedy" in Chinese philosophy, which had to compensate for the inadequate supply of the staple food "Confucianism".

Men who, according to Feng Youlan, had a keen sense of realistic and practicable politics stood for this tendency. They advised princes and feudal lords on how to find ways in the current change in social and political situations of the time, which should enable the individual states to function as effectively as possible. They were called "Men of Method" because they developed "foolproof" methods for effective governance. These methods were designed to give the ruler the greatest possible personal power. A ruler did not have to be virtuous or wise - as Confucius had demanded - and neither had to have superhuman abilities, as the primeval emperors were ascribed to. If someone used their methods, anyone with average intelligence could rule and even rule well.

On the occasion of new government tasks in the course of the power struggles over territories and the dissolution of the clear separation between aristocrats and the common man, the individual princes got used to seeking and applying the advice of such men. The advice was to rule through penalties, sanctions and violence. The ruler had to issue ordinances and laws for this. If successful, the "men of the method" became permanent advisors, and in individual cases they were even appointed prime ministers. The first emperor of China, Qin Shihuangdi , made this system his own thanks to his advisers and had hundreds of scholars killed for the good of the state who had protested against the burning of books.

Among these "men of the method" there were also those who went beyond their advisory work and provided their techniques with rational justifications or theoretical terms and recorded them in writing. According to these writings, the latter - to which Shang Yang , Shen Buhai , Shen Dao and Han Fei are counted - dealt with theories and methods of centralized organization and leadership. Therefore, according to Feng Youlan, it is incorrect to combine the thinking of the legalist school with jurisprudence. If anyone wanted to organize and lead people, then they must have found legalistic theories and practices stimulating and useful. Provided he wanted to follow totalitarian maxims.

"Legalism," said Hubert Schleichert and Heiner Roetz , "soberly bills the people for the purposes of the state and does not ask for their wishes."

Basic concepts of traditional Chinese thought

From a Western point of view, the following terms are not actually "philosophical" terms, but traditional, originally pre-philosophical, partly religious, partly medical concepts of Chinese culture, which have also found their way into various philosophical currents and then each have different remarks have experienced.

Harmony of heaven, earth and man

One often comes across the idea of the four components of nature (ziran,, “being-by-yourself”): human (ren, 人), earth (di, 地), heaven (tian, 天) and “ Dao “(Weg, Lauf, 道). They are closely interrelated and are governed all-encompassing in their own naturalness. In a thinking that integrates everything into a unity, all phenomena in the macrocosm have their correspondence. This principle of regulation is also that of human society. The prerequisite for a happy life is harmony with space. The course ( Dao ) in nature, in the community and in the individual are mutually dependent. A disruption in one area always results in disruptions in the other areas.

The Five Element Teaching and Yin / Yang

Chinese thought knows the five elements wood , fire , metal , water and earth , which are not understood as material substances but as forces:

- Wood : that which forms itself organically from within

- Fire : that ignites sinking things

- Earth : the ground, the balance of the middle

- Metal : that which shapes the outside world

- Water : that which dissolves downwards

The five elements find their correspondence in the different states of change of heaven, earth and man. In later times, the doctrine of the five elements was linked with the yin-yang doctrine, which originally came from divinatorics: The elements are then no longer eternal last substances, but owe their existence to the two polar and correlative principles yin and yang . These are opposing principles that do not fight each other, but complement each other and, through their interaction, bring about all phenomena of the cosmos. Especially in Daoism, Yin and Yang are the two sides of the all-one, constantly changing beings.

The highest world principle

The highest principle is expressed in Chinese thought by three different terms: Shangdi (上帝), Tian and Dao .

Shangdi literally means highest or superior ancestor , ie a god who resides at a fixed point in heaven and under whose eyes world events take place. Kings must also serve him. He is the author of everything that happens, but remains inactive himself. Shangdi manifests as a personification of order in nature, morality and rite. Through him, the abundance of unrelated individual phenomena in the world is put together into an orderly whole. (Originally Shangdi was the deity of the Shang dynasty , but was latersupersededby the deity of the Zhou , the sky ( Chinese 天 , pinyin tiān ).)

Instead of Shangdi , heaven ( tian ) appears as the highest world principle in many texts . It is the source of all things, which together with its subordinate "wife", the earth, produces everything. The term Tian corresponds roughly to that of Shangdi . The human-like features, however, are even less. It is expressly said of him that he does not speak, that he appears soundless and without a trace.

Dao originally means "way", especially the way of the stars in the sky. The word also describes the "meaningful" path that leads to the goal, the order and the law that works in everything. In the Daodejing , the Dao was presented as the highest principle for the first time. The Dao is thought of as something substantial, if invisible. For some philosophers it becomes the primary material from which everything has become. Sometimes he is spoken of as a personal being.

The post-classical period up to colonization

Han period (3rd century BC - 3rd century AD)

During the Han period (206 BC - 220 AD) the Confucian scriptures were canonized; Confucianism developed into a state ideology. Elements of the Yin-Yang school and the I Ching are included. In the period of the fragmentation of the empire (200–600) Confucianism disappears and Daoism becomes predominant.

Tang period (6th - 10th centuries)

Between 500 and 900, during the Tang Dynasty , Buddhism became the dominant spiritual trend in China . To about the 6th century n. Chr.. The Chinese philosophy spread along with the Chinese character ( Han -Schrift , Chinese 漢字 / 汉字 , Pinyin Hànzì , Jap. Kanji , kor. Hanja ) throughout East Asia and mingled with local ( Matriarchy , Shintō ) and supra-regional (Buddhism) teachings.

Song period (10th - 13th centuries)

In the Song Dynasty (960–1280), Neo-Confucianism emerged , which integrated elements of Daoism and Buddhism into classical Confucianism. Neo-Confucianism develops in two schools. The monistic school - represented by Cheng Hao (1032-1085) - emphasizes the unity of the cosmos and the ego and places value on inner awareness. The dualistic school - represented by Cheng Yi (1033–1107) and Zhu Xi (1130–1200), hence also called the “ Cheng Zhu School ” - holds on to the opposition of the cosmos and the self. Zhu Xi reinterprets the Tian as a purely spiritual and transcendent world reason, which defines the essence of heaven and earth. It is different from world and matter and produces them. Among the Confucian thinkers of the Ming Dynasty protrudes Wang Yangming (1472-1528) out, which represents an idealistic philosophy. For him, reason is the highest world principle; outside of it, nothing exists. The intuition is the primary source of knowledge; it also corresponds to conscience.

17.-18. century

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the “School of Reality” ( Chinese 實 學 , Pinyin shixue ) was created. It is a Confucian renewal movement that rejects the Sung and Ming commentaries on the classical scriptures, which for it contain too much speculative information. She advocates a more practical interpretation of Confucianism and declares the original commentaries from the Han period to be the highest authority. During this time, Chinese philosophy was first received in Europe ( Malebranche , Leibniz , Wolff ).

The development since colonization (19th - 20th century)

Towards the end of the 19th century, the collapse of traditional Chinese philosophy began under increasing pressure from the colonial powers. The attempt to synthesize between traditional Confucianism and Western approaches has been undertaken by numerous philosophers. Feng Youlan (1895–1990) is one of the most important and successful philosophers of this time.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the theme of the merging between Chinese and Western philosophy became dominant in China. John Dewey and Bertrand Russell are the first Western philosophers to visit China. Among others, Charles Darwin , Ernst Haeckel , Henry James , Karl Marx , Immanuel Kant , Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche are influential . Hu Shi (1891–1962) tried to combine ancient Chinese traditions with modern pragmatism . Feng Youlan (1895–1990) ties in with Zhu Xi and tries to link Confucianism with Western rationalism . Mou Zongsan combines Kant's intuition with the Confucianian idea of intuition. Jin Yuelin associated modern logic with the term Dao . Thomé H. Fang developed his own neo-Confucian system. In poetic Chinese, he investigated the question of how one can justify the search for a higher inner plane in the age of technology.

Since the mid-1920s, Marxism has been at the center of the discussion, the first representatives of which were Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao .

After the founding of the People's Republic of China (1949), a radical rethink began. The main goals are the development of Marxist theory and the critical examination of the Chinese tradition.

The contemporary picture of the history of Chinese philosophy

Chinese historians of philosophy have been striving since the beginning of the 20th century - in contrast to their Western colleagues - to bring contemporary Chinese philosophy into a fundamental relationship to Western philosophy. Western historians of philosophy see Chinese philosophy as a kind of “preliminary stage” to Western philosophy. The European is therefore classified as the “real” philosophy.

Chinese historians of philosophy paint a picture of the whole of Chinese philosophy in terms of history and also include the more recent developments. Prominent representatives of these scientists include Feng Youlan and Zhang Dainian . Both authors agree that Chinese philosophy is essentially "human life-related". Western historians of philosophy note that humans "play a central role in Chinese philosophy".

The religion - as a component of traditional Chinese philosophy - is considered by modern Chinese philosophy historians as dispensable element of the future philosophizing. The central role of man in both theoretical and practical philosophy also includes the metaphysical values of religion and will thus be able to leave religion behind.

“ In the world of the future one will have philosophy instead of religion. This is entirely in line with Chinese tradition. A person does not have to be religious, but it is actually necessary that he be philosophical. If he is philosophical he has the best of the blessings of religion. "

The Chinese assessment of their own history of philosophy is sometimes viewed differently by European historians. It is referred to as “repression ideology” that, from the perspective of these researchers, mythology and metaphysics were banned from the field of vision very early on. The sometimes total separation between philosophy and religion makes countless phenomena, including Daoism, incomprehensible.

Very recently, Feng Youlan, Zhang Dainian and their successors have tried to portray the history of Chinese philosophy as a conflict between materialism and idealism . The dominance of Marxist ideology should also play an important role here. However, this conflict is also seen by European historians of philosophy for the history of Western philosophy. Chinese historians of philosophy are often at odds with this point of view as to whether a particular philosopher "should be viewed more as 'materialistic' or as 'idealistic'".

Remarks

- ↑ cf. for this section cf. Richard Wilhelm : Introduction to I Ching . Cologne 1987, 14th edition. Pp. 15-18. zeno.org and Wolfgang Bauer : History of Chinese Philosophy . Munich 2006, pp. 17-25.

- ↑ Shiji 130: 3288. (Sima Qian, Shi ji , Peking 1964.) quoted by Bauer, Geschichte der Chinesischen Philosophie , p. 20.

- ↑ On the short maritime history of China in the 15th century, cf. Zheng He .

- ↑ Source: Derk Bodde (Ed.): Fung Yu-Lan: A short history of Chinese philosophy. A systematic accout of Chinese thougt from its origins to the present day . New York (The Free Press) 1966, 30th edition, pp. 16f.

- ↑ Wolfgang Bauer: History of Chinese Philosophy . Munich 2009, 2nd edition, p. 26f.

- ↑ Cf. Richard Wilhelm : Introduction to the I Ching . Cologne 1987, 14th edition. Pp. 15-21.

- ↑ Wolfgang Bauer: History of Chinese Philosophy , pp. 47–50.

- ↑ cf. Shaoping Gan: The Chinese Philosophy. The most important philosophers, works, schools and concepts . Darmstadt 1997, p. 44 f. - Also Fung / Feng Yu-Lan: A short history of Chinese philosophy , pp. 6-10.

- ↑ “ If one follows the mainstream of Chinese philosophy, the Neotaoist, Kuo Hsiang ( Guo Xiang ) changed this point in the 3rd century AD. “Feng Youlan: A Short History of Chinese Philosophy , p. 9.

- ↑ See Hubert Schleichert / Heiner Roetz: Classic Chinese Philosophy , pp. 9–12. - Richard Wilhelm: Chinese Philosophy , pp. 11-13. - Feng Yulan: A Short History of Chinese Philosophy , pp. 3-10. -

- ^ Feng Youlan: A short history of Chinese philosophy . New 1966, p. 156f.

- ^ Feng Youlan: A short history of Chinese philosophy , p. 37.

- ↑ Shaoping Gan: The Chinese Philosophy . Darmstadt 1997, p. 6.

- ↑ Schleichert / Roetz: Classical Chinese Philosophy . Frankfurt / M. 1980, p. 23f. - Also Feng Youlan: A short history of Chinese philosophy , pp. 20-22

- ↑ Kungfutse: Lun Yü. Conversations , 15.23. Translated by Richard Wilhelm, Düsseldorf / Cologne: Eugen Diederichs Verlag, 1975.

- ↑ Kungfutse: Lun Yü. Conversations , 13:18

- ↑ Laotse: Tao Te King , chap. 1. Quoted from G. Wohlfart, “Laozi: Daodejing” in: Franco Volpi (Hrsg.): Großes Werklexikon der Philosophie , Stuttgart 2004

- ↑ Laotse: Tao Te King - The old book of meaning and life. Translated and with a commentary by Richard Wilhelm, Düsseldorf / Cologne: Eugen Diederichs Verlag, 1952, chap. 3

- ↑ Cf. Richard Wilhelm: Chinese Philosophy . Wiesbaden 2007. Reprint of the first edition Breslau 1929, p. 38.

- ↑ See Hellmut Wilhelm : Society and State in China . Hamburg 1960, p. 28.

- ↑ Feng Youlan : A short history of Chinese philosophy , p. 59. - Mozi's presentation here is based on Youlan: A short history of Chinese philosophy , p. 49–59.

- ↑ Wolfgang Bauer: History of Chinese Philosophy . Munich 2009, 2nd edition, p. 66.

- ↑ Cf. Richard Wilhelm : Chinese Philosophy . Wiesbaden 2007. Reprint of the first edition Breslau 1929, p. 39f.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Licia Giacinto: Man and his destiny . In: Henningsen & Roetz (ed.): People images in China . Series: Chinastudien, Wiesbaden 2009, pp. 81–93.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Bauer: History of Chinese Philosophy . Munich 2009, 2nd edition, pp. 64–67.

- ↑ Shaoping Gan: The Chinese Philosophy . Darmstadt 1997, p. 19.

- ^ Jean de Miribel & Leon de Vandermeersch: Chinese philosophy . From the French by Thomas Laugstien. Bergisch Gladbach 2001 (French first edition 1997), p. 63.

- ^ Source of the presentation Feng Youlan: A short history of Chinese philosophy , pp. 156f.

- ↑ Schleichert & Roetz: Classical Chinese Philosophy . Frankfurt a. M. 1980, p. 182.

- ↑ See the Internet encyclopedia on Mou Zongsan

- ↑ Jacques Gernet, The Chinese World. The history of China from its beginnings to the present , Frankfurt am Main, 2nd edition 1983, p. 546

- ↑ Hegel had already made this assessment . Cf. Rolf Elberfeld: The Laozi Reception in German Philosophy . In: Helmut Schneider (ed.): Philosophizing in dialogue with China . Cologne 2000, p. 147.

- ↑ Feng Youlan: A Short History of Chinese Philosophy . New York 1948, p. 5. Quoted in Bauer, History of Chinese Philosophy , p. 22.

- ↑ More contemporary philosophers and an overview of philosophy in China on the English-language website of Peking University ( memento of the original from March 1, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ See the two previous sections: Wolfgang Bauer: History of Chinese Philosophy. Edited by Hans von Ess. Munich 2009, 2nd edition, pp. 17–24.

literature

Essays and books

- Asian Philosophy - India and China , Directmedia Publishing , Digital Library Volume 94, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-89853-494-4

- Wolfgang Bauer : History of Chinese Philosophy. Confucianism, Daoism, Buddhism. Munich: CH Beck, 2001. ISBN 3-406-47157-9

- Wolfgang Bauer: China and the hope of happiness - paradises, utopias, ideals in the intellectual history of China , Munich: DTV, 1989. ISBN 3-423-04547-7

- Marcel Granet : Chinese thinking . Munich: Piper, 1963; New edition: Frankfurt a. M .: Suhrkamp, 1985, ISBN 3-518-28119-4 ; Original: La pensée chinoise . Paris: La Renaissance Du Livre, 1934

- Hou Cai: "Literary essay - Chinese philosophy after reform and opening up (1978–1998)" in: German Journal for Philosophy , 2000; 48 (3): 505-520

- Anne Cheng: Histoire de la pensée chinoise , paperback edition, Paris: Le Seuil, 2002, ISBN 978-2-02-054009-4

- Antonio S. Cua (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Chinese philosophy , New York, NY [u. a.]: Routledge, 2003

- Zhang Dainian: Key Concepts in Chinese Philosophy. Translated and edited by Edmund Ryden. New Haven and London 2002.

- Alfred Forke : History of ancient Chinese philosophy , Hamburg 1927

- Shaoping Gan: The Chinese Philosophy. The most important philosophers, works, schools and concepts . Darmstadt 1997.

- Ralf Moritz: The philosophy in old China , Berlin: Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, 1990. ISBN 3-326-00466-4

- Hubert Schleichert / Heiner Roetz : Classical Chinese Philosophy . 3. edit again. Edition Frankfurt a. M .: Klostermann, 2009 ISBN 3-465-04064-3

- Helmut Schneider (Ed.): Philosophizing in Dialogue with China. Cologne 2000.

- Ulrich Unger : Basic Concepts of Ancient Chinese Philosophy , Darmstadt: WBG, 2000 ISBN 3-534-14535-6

- Hellmut Wilhelm : Society and State in China . Hamburg 1960.

- Richard Wilhelm : Chinese Philosophy . Wiesbaden 2007. (New edition of the Breslau 1929 edition.)

- ders .: I Ching . Cologne 1987, 14th edition.

- Feng Youlan : A Short History of Chinese Philosophy . New York 1948.

Magazines

- Asian philosophy. An international journal of Indian, Chinese, Japanese, Buddhist, Persian and Islamic philosophical traditions , since 1991

- Chinese studies in philosophy. A journal of translations , 1969–1996

- Dao. A journal of comparative philosophy. Official publication of Association of Chinese Philosophers in America , since 2001

- Journal of Chinese philosophy, since 1973

Web links

- David L. Hall, Roger T. Ames: Chinese philosophy , in E. Craig (Eds.): Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy , London 1998.

- David Wong: Comparative Philosophy: Chinese and Western. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Franklin Perkins: Metaphysics in Chinese Philosophy. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Yih-Hsien Yu: Modern Chinese Philosophy (1901-1949). In: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Bryan W. Van Norden: Essential Readings on Chinese Philosophy (extensive bibliography) - English

- Gregor Paul : Global Ethics and Chinese Resources (2001)