Chinese tea culture

The Chinese tea culture is an important part of Chinese culture and the world's oldest of its kind. The Japanese tea culture has its roots in China , but has been independently developed over time. China also has its own tea ceremony, which is translated as the art of tea ( Chinese 茶藝 / 茶艺 , pinyin cháyì ). After the suppression of public tea culture during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1977) and the closure of many teahouses, it was only really widespread in southern and western China and Taiwan . However, tea drinking has remained unchanged in families to this day, with most Chinese drinking unsweetened green tea . In the course of China's economic rise, the traditional tea culture is also increasingly coming into its own.

Tea cultivation and types of tea

Chinese tea is mainly grown in the south of the country. The green tea comes from the east Chinese provinces of Zhejiang , Anhui and Fujian , the oolong tea from Fujian or Taiwan, the yellow tea from Hunan and the red tea from Sichuan and Yunnan .

In China there are essentially six types of tea:

- 綠茶 / 绿茶 , lǜchá - " green tea "

- 白茶 , báichá - " white tea "

- 黃 茶 / 黄 茶 , huángchá - " yellow tea "

- 烏龍茶 / 乌龙茶 , wūlóngchá - " Oolong tea " (semi-oxidized tea)

- 普洱茶 , pǔ'ěrchá - " Pu-Erh Tea " (post-fermented tea from the city of Pu'er)

- 紅茶 / 红茶 , hóngchá - " red tea " (German black tea)

It is also quite common to classify scented teas (such as jasmine tea ) as the sixth variety instead of yellow tea .

When choosing a good tea, freshness (natural not too light and not too dark tea leaf color), naturalness (without preservatives and without odorous substances), single tea leaf (whole tea leaves instead of tea powder or dust) and similarity of the natural product ( individual tea leaves are similar in color and shape) the most important criteria.

history

Earliest references

China is the motherland of tea cultivation. However, when exactly this started cannot be proven. What is certain is that as early as 221 BC Under the Qin Dynasty there was a tea tax. Techniques to preserve the tea for transport were still unknown. Tea was therefore mostly drunk in the southern Chinese areas where the plants were grown. In Chinese literature, tea is mentioned for the first time around 290 in the history of the Three Kingdoms : Sun Hao (r. 264–280), the last emperor of the Wu dynasty , is said to have so strongly attributed alcohol that his court historian Wei Zhao made wine occasionally replaced with tea to survive the drinking bout. In a collection of stories from the time of the Western Jin (265-316) it is mentioned that "real tea reduces people's need for sleep" and should therefore be avoided. Tea is mainly associated with its region of origin, Sichuan , but was already known beyond the region. Other early writings that mention tea are mostly preserved in the anecdotal collections in Lu Yu's work Chajing (780). Research into early literary sources is made difficult by the fact that a uniform character for tea ( 茶 , chá ) did not appear until the 8th century. Originally the character had another horizontal line ( Chinese 荼 , Pinyin tú - "bitter herb"), so that it is not always possible to tell whether an old text actually refers to tea or another bitter-tasting plant.

Tang time

At the time of the Tang Dynasty (618–907), tea replaced the alcoholic beverages, which until then had been consumed as luxury goods at meetings of the social elite. Benn (2015) suspects that the custom of drinking tea spread in connection with Buddhist teachings. Buddhist monks drank tea to stay awake or as medicine during their meditation . According to Lu Yu, this custom is said to have first been introduced in the Lingyang monastery on Mount Tai and from there to have spread to other monasteries. After a while, the monks began to grow tea themselves and to trade with it. Tang-era poets such as Li Bai and Du Fu dedicated poems to tea in which they connected tea drinking with topics such as longevity and transcendence, friendship, festivity and parting. The world's first book on tea , the Chajing, by Lu Yu, who grew up as an orphan in a Buddhist monastery and was in close contact with Buddhist monks and scholars throughout his life , was also published during the Tang period . The legend that Shennong discovered the properties of the tea plant was first described in Chajing .

Song time

The time of the Song Dynasty (960–1279) brought further important developments in the history of tea: Fujian Province was developed as a cultivation area for the tribute tea to be paid directly to the imperial court. Before the Song era, tea was not grown there in any significant way, and the region was economically underdeveloped. The development of paper money and credit led to a general boom in trade. In Sichuan, tea cultivation had long been an extensive, profitable economic factor; Tea from the region was traded over long distances on various tea routes . In the course of the reforms of Wang Anshi (1021-1086), a tea agency was established in Sichuan that bought tea at fixed prices. The tea was brought to Tibet and India on the Tea Horse Road and exchanged there for horses. While tea - usually pressed in the form of bricks or round cakes - found its way into the Tibetan and Indian tea culture, horses remained an important pillar of China's military power from beyond the country's borders until the horse trade was banned in 1735.

At this time, tea appeared for the first time as a drink that was served at meetings of nobles and Buddhist scholars and evaluated according to refined aesthetic criteria (shape of the leaves, scent, taste). Tea drinking spread among the social elite. Tea competitions were used for entertainment and to represent one's own sophisticated taste and replaced the previously common alcoholic drinking games. Technical advances in ceramic production made it possible to develop special tea products for the upper class. Wide, flat tea bowls made of black porcelain ( 建 , jiàn ), which were made in Jianyang Prefecture, were widespread . The connection of tea, music and conversation that emerged in the Tang period was refined in the Song period; Tea connoisseurship became the hallmark of literati . For the first time, counterfeits of famous teas are also documented.

Tea was traded either in the form of pressed flat cakes ( pian cha ) or loose leaves ( san cha ) at the time of the song . Poetic trade names and particularly valuable packaging emphasized the character of certain types of tea as luxury goods. Books such as the 1107 about tea from the Daguan reign (Daguan cha lun) by Emperor Song Huizong (r. 1100–1126) are no longer only dedicated to the drink itself, but also to the details of the cultivation of the tea plants, the selection and processing the leaves and the preparation of the tea. A special tea was made in the Jian'an District of Fujian. The Northern Plantation ( Beiyuan ) there had already been nationalized at the time of the Southern Tang and supplied the imperial court until the beginning of the Ming period. The tea, which was pressed into a flat round cake, acquired a waxy sheen through processing and was therefore called "wax tea" ( la cha ). Loose leaf tea was produced in Sichuan, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Fujian.

For preparation, both the tea cake and loose tea leaves were wrapped in paper and then crushed with a hammer, the fragments then ground in a roller mill and finally sieved. The fine tea powder was placed in a preheated tea bowl and poured with hot water from a tall, lidded pot with a long, thin spout ( ping ). The tea was whipped with a bamboo tea whisk. This technique was called diancha (roughly: "show tea") because the water jet from the pot "pointed" at the tea.

Ming Dynasty

In 1391, Emperor Hongwu , the founder of the Ming dynasty , forbade the payment of tribute in the form of pressed tea, as its elaborate production "overwhelmed the people's strengths". In the future, loose tea leaves should be paid as a tribute. Zhu Quan , a son of Hongwu, who led a secluded life as a hermit , founded a new school of tea art: loose, dried leaves were now infused directly. The equipment necessary for its preparation received special attention; scholars often worked together with artists to design vessels and devices according to their ideas. The new preparation required the development of a special type of vessel: For the first time, special teapots were made from porcelain or unglazed clay. While tea sets made of porcelain or precious metals were common at the imperial court and in the residences of the high nobility, clay jugs from Yixing were particularly valued by scholars and intellectuals.

Monks from Songluo Mountain in Anhui developed a new technique to prevent the green tea leaves from oxidizing in the air: If this was previously done by steaming, the tea leaves were now heated ("roasted") in a dry pan. The new technology spread to other growing areas. In the 16th century, tea growers in the Wuyi Mountains discovered that the tea leaves could also be partially oxidized before they were roasted. In this way a darker tea with an intense taste was created. The Wuyi Mountains are considered the origin of Oolong tea.

Cultural Revolution and Modern China

In earlier times there were many public teahouses in China, but they had to close during the Cultural Revolution . Today there are public teahouses in the cities again. Under Mao Zedong , not only intellectuals but also many tea masters fled to the Republic of China in Taiwan . In the course of Deng Xiaoping's reform and opening-up policy , Chinese traditions were revived and put at the service of new political and economic goals. Enjoying tea is no longer considered a characteristic of the "exploiting class", but is propagated by the Chinese government as part of the cultural embodiment of " socialism with Chinese characteristics ". As the world's largest tea producer (2018: 2.8 million tons), tea is also of economic importance for modern China.

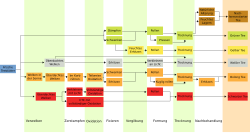

preparation

Chinese tea culture distinguishes three historical schools: In the Tang Dynasty, the tea was boiled together with the water until the water took on the correct color, using powdered tea. Since a pinch of salt has been added to this tea, this method is also known as the "school of salted powdered tea". During the Song Dynasty, the art of tea was refined, the tea powder was now poured with hot water and whipped with a bamboo whisk. The art of the tea masters consisted in keeping the foam as long as possible. This is called the "school of foamed jade". Whole tea leaves were then used in the Ming phase, this period is also called the “school of the fragrant leaf”. At this time, the ceremony called Gongfu Cha ( 工夫茶 , Gōngfu chá ) was created. To this end, Oolong - or pu-erh tea used.

Tea ceremony

The Chinese tea ceremony was never developed into such a sophisticated ritual as the Japanese : Its execution is less tied to a location, such as a tea house or tea room. The focus is on enjoying the tea together, the necessary equipment and actions serve to ensure the best possible preparation.

There are several types of tea ceremony in China, each of which uses different types of tea. The most common type is Gongfu Cha for the preparation of Oolong and Pu-Erh tea . Here, the tea bowls and the pot are first cleaned with hot water and preheated. Then the tea leaves are put into the pot and hot water is poured over them. This first infusion only opens the leaves and softens the bitterness of the later infusions - it is immediately poured into the bowls and not drunk. It is called "Infusion of the good smell". The pot is filled with water a second time, the tea steeps in it for about 10 to 30 seconds. The infusion is then either poured "in layers" into the tea bowls or first in a decanter so that every guest receives the same quality of infusion. This is the "infusion of good taste". The infusions are repeated several times, whereby the tea leaves remain in the pot. If the tea quality is good, several infusions are possible (infusions of the "long friendship"). You let the tea brew a little longer than before. Since the tea leaves should not continue to infuse immediately after an infusion, the tea is poured out of the pot immediately. Every infusion tastes different. In a refined variant of the art of tea, the infusion is first poured into scented cups and from these into the drinking bowls; the tea drinker then first assesses the aroma of the tea by smelling the emptied scent cup.

Regional preferences

Although most Chinese people drink green tea, there are certain differences. Jasmine tea is very popular in Beijing and is also offered in many Chinese restaurants. Black tea is drunk in southern China's Fujian Province . The Tibetans use so-called "brick tea", powdered green tea, which is pressed into blocks with the help of rice water and dried. In this form, the tea was sold throughout China at the time of the Tang Dynasty. The block is boiled in a jug and seasoned with a little salt and, in honor of guests, with yak butter. Mongolian shepherds in northern China add milk and a pinch of salt to their tea. In southern China, tea is also known to be prepared with fruit, which is served to guests as a sign of respect. In the province of Hunan , the tea for guests is mixed with roasted soybeans , sesame seeds and slices of ginger . After emptying the bowl, these additions are eaten.

Yum Cha

Yum Cha ( Chinese 飲茶 / 饮茶 , Pinyin yǐn chá , Cantonese jam2 caa4 ) is a canton Chinese term and literally means “drink tea”. It refers to a special tea meal that is served with various warm bites known as dim sum . This meal is mostly common in Guangdong Province , Hong Kong, and Macau . It can be a snack or a main meal. It is offered in tea houses . But nowadays there are mostly large restaurants in which families, especially on weekends, have this meal as a kind of brunch and can last for several hours.

Teaware

Originally the Chinese tea set consisted only of tea bowls; The tea was boiled in large kettles, from which it was then poured with ladles. During the Song Dynasty , scholars began to view and collect tea utensils as precious objects, in parallel with the development of the tea ceremony.

The oldest known teapots that were known to have been used in China were not made of porcelain, but of reddish ceramic and were made in Yixing during the Ming Dynasty . One of the most famous early master potters was Shi Dabin ( Chinese 時 大 彬 / 时 大 彬 , Pinyin Shí Dàbīn ), active in the second half of the 16th century. The scholar and government official Chen Mansheng ( Chinese 陳曼生 / 陈曼生 , Pinyin Chén Mànshēng , 1768–1822), who worked closely with various potters and is said to have designed 18 different shapes for teapots, was also of great importance for the development of Yixing tea ceramics . He rejected the mass production that began at that time. In the 18th century it became fashionable to decorate teapots with calligraphy and drawings. The jugs were considered works of art and were signed by the respective potters. At the time of Emperor Kangxi , teapots were also enamelled or coated with layers of lacquer into which patterns were scratched.

Outside of China, tea sets made of porcelain became famous. The most famous internationally is the blue and white porcelain. The largest porcelain factory for this was in Jiangxi Province , in the city of Jingdezhen . This decor was created during the Yuan Dynasty and was mentioned by Marco Polo in his travelogue (" Il Milione "). However, it was also used for dinnerware from the beginning . The emperor had the monopoly for the export of porcelain.

After the Opium War , the potters and porcelain manufacturers lost their importance. The cultural revolution then meant the end of all handicrafts for a while, as it was considered reactionary. Only simple utility ceramics were produced. Liberalization then took place at the end of the 1970s.

Social importance

In China, guests are always treated to tea as a sign of appreciation. This gesture still exists within families to this day. The younger generation offers tea to the older generation to show their respect. The ability to make good tea used to be an important criterion when choosing future daughters-in-law. In the more affluent Han Chinese families , the teapot indicated the social status of the drinkers: for the servants, day laborers, etc. there was a large pewter jug that stood in a wooden bucket with an opening. If you held the bucket at an angle, the tea flowed out; so you don't need a tea bowl. A smaller porcelain pot was intended for the family and guests. The head of the family and guests of honor, however, drank their tea from tea bowls with lids.

Tea also plays an important role as a symbolic gift in many customs, especially wedding and engagement customs. The engagement gifts of the Han Chinese are still called "tea gifts" today. This dates back to the Song Dynasty when it became customary to bring tea to the family of the chosen bride. The matchmaker was called "tea caddy carrier". In Jiangsu Province , the groom was received with tea by the male relatives in the bride's house on the wedding day, and he had three cups to drink, called "the tea of opening the door." Then he was allowed to wait for the bride. In the province of Hunan tea was part of the wedding party. The bridal couple in turn offered tea to all guests as a token of appreciation, who in turn thanked them with gifts of money. Then the couple drank a cup of tea “to put the pillows together”. With the Bai nationality, a tea ritual in the bride's bedroom is one of the wedding customs. The couple offers tea to the guests there three times in a row, first bitter, then sweetened tea with nut kernels, and finally sweet milk tea - first bitter, then sweet, then a taste for reflection.

In the past, a daughter-in-law was also expected to know how to make good tea. The day after the wedding she had to get up early and serve tea to her in-laws. It was also common for the eldest son or daughter of a family to bring their parents a cup of tea every morning on behalf of the children.

gallery

See also

- Tibetan tea culture

- Japanese tea ceremony

- Chajing

- National Chinese Tea Museum

- Gong Fu (tea preparation)

supporting documents

- ↑ How do you choose a good tea?

- ^ Albert E. Dien: Six Dynasties Civilization . Yale University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-300-07404-8 , pp. 362 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Benn (2015), pp. 26-27

- ↑ James A. Benn: Tea poetry in Tang China. In: Tea in China. A religious and cultural history (Chapter 4) . University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 2015, ISBN 978-0-8248-3964-2 , pp. 72-95 .

- ↑ James A. Benn: The patron saint of tea: Religious aspects of the life and work of Lu Yu. In: Tea in China. A religious and cultural history (Chapter 4) . University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 2015, ISBN 978-0-8248-3964-2 , pp. 96-116 .

- ↑ a b c d James A. Benn: Tea: Invigorating the body, mind and society in the Song dynasty. In: Tea in China. A religious and cultural history (Chapter 6) . University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 2015, ISBN 978-0-8248-3964-2 , pp. 117-144 .

- ↑ Benn (2015), pp. 119–120

- ↑ Marvin Sweet (Ed.): The Yixing effect: Echoes of the Chinese scholar . Foreign Languages Press, Beijing ( marvinsweet.com [PDF; accessed January 25, 2018]).

- ↑ Mair & Hoh (2009), p. 110

- ↑ Benn (2015), p. 175

- ↑ Mair & Hoh (2009), p. 113

- ↑ http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-11/15/c_137608915.htm

- ↑ Information on blue-white porcelain

- ↑ On the history of the Chinese teapots

literature

- James A. Benn: Tea in China. A religious and cultural history . University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 2015, ISBN 978-0-8248-3964-2 .

- Blofeld, John: The Tao of tea drinking. On the Chinese Art of Preparing and Enjoying Tea , Otto Wilhelm Barth Verlag, 1986.

- Hu, Hsiang-Fan: The secret of tea , Theseus publishing house, 2002. ISBN 3-89620-193-X .

- Victor H. Mair, Erling Hoh: The True History of Tea . Thames & Hudson, 2009, ISBN 978-0-500-25146-1 .

- Li-Hong Koblin, Sabine H. Weber-Loewe: tea time; Drachenhaus Verlag, Esslingen 2017; ISBN 978-3-943314-37-3

- Kuhn, Sandy: Drink tea with Buddha. An introduction to the Chinese tea ceremony , Schirner Verlag, 2011. ISBN 3-8434-1033-X .

- Liu, Tong: Chinese Tea. A Cultural History and Drinking Guide. China International Press, 2010. ISBN 978-7-5085-1667-7 .

- Schmeisser, Karl / Wang, Jiang: Tea in the tea house , ABC Verlag, Heidelberg 2005. ISBN 3-938833-01-7 .

- Wang, Ling: The Chinese Tea Culture , Publishing House for Foreign Language Literature, Beijing 2002. ISBN 7-119-02146-X .