Early Dynastic Period (Mesopotamia)

| The old Orient | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Timeline based on calibrated C 14 data | |

| Epipalaeolithic | 12000-9500 BC Chr. |

| Kebaria | |

| Natufien | |

| Khiamien | |

| Pre-ceramic Neolithic | 9500-6400 BC Chr. |

| PPNA | 9500-8800 BC Chr. |

| PPNB | 8800-7000 BC Chr. |

| PPNC | 7000-6400 BC Chr. |

| Ceramic Neolithic | 6400-5800 BC Chr. |

| Umm Dabaghiyah culture | 6000-5800 BC Chr. |

| Hassuna culture | 5800-5260 BC Chr. |

| Samarra culture | 5500-5000 BC Chr. |

| Transition to the Chalcolithic | 5800-4500 BC Chr. |

| Halaf culture | 5500-5000 BC Chr. |

| Chalcolithic | 4500-3600 BC Chr. |

| Obed time | 5000-4000 BC Chr. |

| Uruk time | 4000-3100 / 3000 BC Chr. |

| Early Bronze Age | 3000-2000 BC Chr. |

| Jemdet Nasr time | 3000-2800 BC Chr. |

| Early dynasty | 2900 / 2800-2340 BC Chr. |

| Battery life | 2340-2200 BC Chr. |

| New Sumerian / Ur-III period | 2340-2000 BC Chr. |

| Middle Bronze Age | 2000-1550 BC Chr. |

| Isin Larsa Period / Ancient Assyrian Period | 2000–1800 BC Chr. |

| Old Babylonian time | 1800–1595 BC Chr. |

| Late Bronze Age | 1550-1150 BC Chr. |

| Checkout time | 1580-1200 BC Chr. |

| Central Assyrian Period | 1400-1000 BC Chr. |

| Iron age | 1150-600 BC Chr. |

| Isin II time | 1160-1026 BC Chr. |

| Neo-Assyrian time | 1000-600 BC Chr. |

| Neo-Babylonian Period | 1025-627 BC Chr. |

| Late Babylonian Period | 626-539 BC Chr. |

| Achaemenid period | 539-330 BC Chr. |

| Years according to the middle chronology (rounded) | |

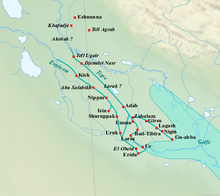

The early dynastic period or early dynasty (abbreviated FD or Ed for early dynastic ) is a historical epoch from the early history of Mesopotamia (where Sumer and Akkad are the core areas), which began around 2900 BC following the Ǧemdet-Nasr period . And ended with the establishment of the kingdom of Akkad under Sargon I around 2340. With the emergence of writing around 3200 BC In Sumer, archaeological and written sources from the early dynastic period can be combined for the first time, which contributes to a more differentiated observation of Mesopotamian history.

Archaeological subdivision

On the basis of excavations of the ruins of Tell Agreb , Tell Asmar and Hafa , i , which took place in 1930 in the Diyala area (east of Baghdad ), the early dynastic period was divided into three parts (here the "middle" chronology):

- Early Dynastic I (2900-2750 BC)

- Early Dynastic II (2750–2600 BC)

- Early Dynastic III a / b (2600-2450 / 2340 BC)

The "short" chronology extends from 2800 to 2230 BC. A long chronology represented by Wolfram Nagel dates between 3100 and 2440 BC. Chr.

Written certificates

The most famous written document of the early dynastic period is the so-called Sumerian King List . In addition, a wider range of different texts appears in this epoch. In addition to texts relating to economics and administration, there are also religious, literary and legal texts.

City-states

The city-states in Sumer and Akkad were ruled autonomously by a city prince (called ensi or lugal ). Since most of the city-states in the lowlands between the Euphrates and Tigris were in a limited metropolitan area, there were often disputes and wars among the city-states, with each prince naturally constantly striving to secure his own territory and to gain new territory. The strong fortifications of the Sumerian and Akkadian cities, which were built especially during this period, testify to this.

population

One of the main characteristics of this epoch is certainly the rural exodus, which attracted large numbers of people to the large cities of the water-rich areas of Mesopotamia. On the one hand, drought in the arid areas and, on the other hand, the increasing salinization of the soil caused by humans, led to a decline in the rural population.

As a direct consequence, the population of the cities increased rapidly, which inevitably led to conflict. Court documents from the time bear witness to a wide variety of disputes.

State

Temple and palace

In the early dynastic epoch a separation between state and temple occurs for the first time in the history of Mesopotamia. Compared to the older Uruk period , where no differentiated statements can be made about certain functions of buildings in the sacred area or the related professional groups such as priests, the characteristics of sacred buildings (temples) and secular buildings (palaces, representative buildings) now make it clearer. In addition, there is a social change associated with it. A noble upper class emerged, consisting of privileged families, which were closely connected to the ruling family. This change in society brought with it a constant striving for luxury and prestige among the upper classes; Visible on lavishly decorated graves and so-called follower graves such as the royal grave of Ur , where the entire court followed the deceased to his death.

Regarding the architecture of the temples, it can be said that from now on they were no longer built at ground level, but on a kind of terrace, which provided a solid foundation. As in earlier times, the temples were also walled here.

economy

The economy represented a kind of "planned economy" in the early dynastic period. Palace and temple controlled trade, agriculture and commercial activity and regulated taxes. However, as the king's officials increasingly enriched themselves with the taxes, this led to the abuse of power and exploitation of the already disadvantaged population. A king who intervened against this grievance in order to protect the exploited and thus indebted people was Urukagina of Lagasch (also Iri-kagina), who at the end of this epoch around 2350 BC. Lived. He drafted reform laws that included debt relief, deliverance from bondage, and other socio-political advances. In setting up these reforms, as well as in every act that he carries out as king towards the state, he invokes Ningirsu , the city god of Lagasch. Representing this justification of royal rule and associated duties as being willed by God is seen throughout early Mesopotamian history.

Footnotes

- ↑ in the Levant

- ↑ a b c d in southern Mesopotamia

- ↑ a b c in northern Mesopotamia

- ↑ Nagel, Wolfram; Eder, Christian; Strommenger, Eva: Archaic chariots in the Middle East and India. Construction and use. Reimer, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-496-01568-0 .

See also

literature

- Bär, Jürgen: Early high cultures. Theiss, Stuttgart 2009.

- Nissen, Hans Jörg: History of ancient Near East. Munich 2012. pp. 62–73.