Umm Dabaghiyah Sotto culture

| The old Orient | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Timeline based on calibrated C 14 data | |

| Epipalaeolithic | 12000-9500 BC Chr. |

| Kebaria | |

| Natufien | |

| Khiamien | |

| Pre-ceramic Neolithic | 9500-6400 BC Chr. |

| PPNA | 9500-8800 BC Chr. |

| PPNB | 8800-7000 BC Chr. |

| PPNC | 7000-6400 BC Chr. |

| Ceramic Neolithic | 6400-5800 BC Chr. |

| Umm Dabaghiyah culture | 6000-5800 BC Chr. |

| Hassuna culture | 5800-5260 BC Chr. |

| Samarra culture | 5500-5000 BC Chr. |

| Transition to the Chalcolithic | 5800-4500 BC Chr. |

| Halaf culture | 5500-5000 BC Chr. |

| Chalcolithic | 4500-3600 BC Chr. |

| Obed time | 5000-4000 BC Chr. |

| Uruk time | 4000-3100 / 3000 BC Chr. |

| Early Bronze Age | 3000-2000 BC Chr. |

| Jemdet Nasr time | 3000-2800 BC Chr. |

| Early dynasty | 2900 / 2800-2340 BC Chr. |

| Battery life | 2340-2200 BC Chr. |

| New Sumerian / Ur-III period | 2340-2000 BC Chr. |

| Middle Bronze Age | 2000-1550 BC Chr. |

| Isin Larsa Period / Ancient Assyrian Period | 2000–1800 BC Chr. |

| Old Babylonian time | 1800–1595 BC Chr. |

| Late Bronze Age | 1550-1150 BC Chr. |

| Checkout time | 1580-1200 BC Chr. |

| Central Assyrian Period | 1400-1000 BC Chr. |

| Iron age | 1150-600 BC Chr. |

| Isin II time | 1160-1026 BC Chr. |

| Neo-Assyrian time | 1000-600 BC Chr. |

| Neo-Babylonian Period | 1025-627 BC Chr. |

| Late Babylonian Period | 626-539 BC Chr. |

| Achaemenid period | 539-330 BC Chr. |

| Years according to the middle chronology (rounded) | |

The Umm Dabaghiyah Sotto culture is the oldest group of finds from the Ceramic Neolithic in northern Mesopotamia . It is named after the decisive sites Umm Dabaghiyah and Tell Sotto in today's Iraq , which show the most comprehensive picture of this archaeological culture . The term proto-Hassuna culture is often used synonymously , since the Umm Dabaghiyah Sotto culture is to be seen as a direct preliminary stage of the actual Hassuna culture . A generally accepted agreement on the designation of this corresponding epoch has not yet occurred.

Dating

At the latest since the excavations in the Jazīra in the early 1970s by Diana Kirkbride ( Umm Dabaghiyah ) and Nikolai O. Bader ( Tell Sotto ), more and more finds have been discovered, the characteristic features of which reveal a uniform cultural group that was already in the centuries before it appeared the Hassuna pottery colonized the northern Mesopotamian plain. However, due to the lack of reliable radiocarbon data , unequivocal dating is difficult and relies largely on comparison. For example, an early construction phase on Tell 2 in Telul eth-Thalathat was identified with the Umm Dabaghiyah Sotto culture and dated to 5,850 ± 80 BC. To be dated; also lie C 14 evaluations for a layer of the settlement mound Kashkashok II before, the v a period of 5930-5540. And set a rough time frame for the Proto-Hassuna goods contained therein. No radiocarbon values exist for Umm Dabaghiyah and Sotto . In the latter, however, the constant development of ceramics can be traced very well - the finds from layers 1-6 show strong parallels to Umm Dabaghiyah , while the ceramics from layers 7-8 show a striking resemblance to the archaic Hassuna ware and thus the first phase of the subsequent culture in northern Mesopotamia has already been documented. These clues provide at least approximate clues, so that a period of about 6,000-5,750 BC. Has established.

Distribution area and important sites

While earlier cultures mainly settled the hilly areas that enclose northern Mesopotamia in the shape of a crescent, now more settlements emerged in the fertile plains of the Euphrates and Tigris . The material legacies of these communities extend over large parts of the Jazira from the foothills of the Zāgros Mountains in the east to the banks of the Chabur in the west. However, the focus is on the area on the upper Tigris south of the Jabal Sinjar in the region around Mosul . Umm Dabaghiyah , around 26 km west of Hatra , is the southernmost of these facilities and represents a kind of outpost for hunting purposes. Sotto is 2 km west of the Yarim Tepe excavation site on the northern edge of the Upper Mesopotamian Plain in the immediate vicinity of the Kül Tepe sites in the west and Telul eth-Thalathat, about 40 km away, in the east. In the northeast of Syria, the facilities of Kashkashok II and Khazna II can be found near al-Hasakah on the Chabur. The eastern border is marked by Gird Ali Agha on the Great Zab .

Material characterization

Isolated older sites such as Jarmo or Maghzaliya already had knowledge of the production of ceramics and are therefore considered to be classic representatives of the ceramic Neolithic before the heyday of the Umm Dabaghiyah Sotto type, but did not achieve their diversity in their legacies. From around 6,000 BC Not only is there a widespread use of ceramic goods in northern Mesopotamia, there is also greater correspondence between the finds from the individual settlements and characterize the image of a coordinated network.

Ceramics

The ceramic vessels of this group of finds are primarily simple in design, have a thick, vegetable -lined wall and were fired at a low temperature. Their rough shapes were created by hand using the bead technique , as the potter's wheel had not yet been invented. In addition to these coarse-grained goods, ceramics made of finer material were also found, which may have been imported. Although the vast majority of the vessels found are undecorated, there are also some specimens painted with ocher , others were polished or decorated with incisions. Simple motifs such as dots, circles, ticks, triangular or herringbone patterns, which are usually attached below the vessel edges, are dominant. Bowls with a grooved bottom, which were probably used to peel legumes, can also be found in Hassuna ceramics. Particularly noteworthy are finely modeled, practically designed decorative elements that depict, for example, human eyes and ears, animal heads, snakes, anthropomorphic figures or crescent moon. Examples are round or oval vessel shapes, simple pots, bowls and bowls, but also double-conical containers with a height of up to 50 cm.

Stone inventory and small finds

The production of everyday objects made of stone was still part of the general picture. Tools for scraping, cutting and drilling were made from locally available flint and obsidian - mostly finished - imported from Lake Van or Göllü Dağ from Anatolia. With the exception of Umm Dabaghiyah , there is a predominance of sickle blades and common tees . Axes, flat hatchets, hoes and burins were created for example. B. from marble and basalt ; mostly stalked projectile points can be found in small numbers at most sites. Furthermore, polished vessels made of soft stone such as alabaster or marbled limestone were excavated, but also carefully shaped products made of hard stone - furthermore, millstones and club heads were found. Plaster of paris was used for plastering architecture, but also for modeling, lining baskets or making simple bowls.

The particular finds include female figurines made of clay, some of which have been painted or decorated with incisions. Large numbers of sling projectiles have also been excavated, for example a weapons store with over 2,400 fired clay balls with a diameter of up to 15 cm was found in Umm Dabaghiyah . Weaving weights made of plaster, clay spindle whorls as well as awls and needles made of bones are evidence of textile and leather processing . Beads for bracelets and collars were made from various minerals and rare finds of copper document the first metallurgical work in northern Mesopotamia.

Settlement style and economic fundamentals

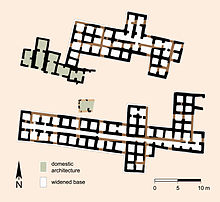

The people of the Umm Dabaghiyah Sotto culture lived in village communities of 20 to 30 people per settlement. Small, mostly rectangular buildings were usually built using the Tauf construction method, in which still moist clay material was piled up to form walls by hand, or with air-dried, hand-formed mud bricks and grouting mortar . The walls and hallways of the houses were mostly heavily plastered, as was the interior consisting of benches, storage niches, shelves and stoves that were connected to a stove on the outside of the house - a smoke vent provided for exhaust air. As in Çatalhöyük, access to the small rooms was mainly via the roofs, which were probably used as work areas. While in Sotto each house from a single 12-16 m 2 was large room, several houses possessed in Umm Dabaghiyah via tiny, 50-74 cm tall door connections between the spaces to crawl through through which one. In addition, there is functional architecture such as storage buildings, pits for firing ceramics or heavily plastered tub-like structures with drainage channels, probably used as basins for tanning hides and skins.

Much of their food supply came from rain-fed agriculture , with the help of which they cultivated emmer , einkorn , primitive barley (naked barley), peas and lentils . The exception here is the settlement of Umm Dabaghiyah , which was obviously designed for large-scale hunting of wild animals. With specialized hunting methods (nets, pitfalls) gazelles , onagers , wild boars, aurochs , hyenas , wolves, hares and birds were hunted. Domesticated animals mainly included sheep and goats, as well as cattle, pigs and dogs.

Wall painting and burials

Little is known about everyday life and the intangible identities of these people. Evidence of this is provided by pictures that were painted in Umm Dabaghiyah with red ocher on the inner walls of the houses. They presumably depict chase and hunting scenes with wild asses that were caught with the help of hooks and nets. Other frescoes show wavy lines, possibly depicting vultures in flight, another motif called spiders and eggs also consists of wavy lines and points.

Nine burials that were excavated in Sotto provide information about how people of the Proto-Hassuna period dealt with death . All were placed either directly under the house floor or in close proximity to the house; 8 of these funerals were children aged 1–3 years. The bodies were usually cut up before burial so that they could be placed in vessels or shallow pits. Two of these burials contained grave goods in the form of containers with animal bones and jewelry, including pearls made of lapis lazuli and a twisted copper plate.

literature

- Roger Matthews : The early prehistory of Mesopotamia. 50,000 - 4,500 BC (= Subartu. 5). Brepols, Turnhout 2000, ISBN 2-503-50729-8 .

- James Mellaart : The Neolithic of the Near East. Thames & Hudson, London 1975, ISBN 0-500-79003-5 .

- Hermann Parzinger : The children of Prometheus. A history of mankind before the invention of writing. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66657-5 .

- Norman Yoffee & Jeffery J. Clark : Early Stages in the Evolution of Mesopotamian Civilization: Soviet Excavations in Northern Iraq. University of Arizona Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0-816-51393-2 .

Footnotes

- ↑ in the Levant

- ↑ a b c d in southern Mesopotamia

- ↑ a b c in northern Mesopotamia

- ↑ While Kirkbride (1972) and Mellaart (1975) on a value of layer XV of 5,570 ± 80 BC. Referring to BC and decreeing the finds before this time, Matthews (2000) names 3 radiocarbon values of the layers XV-XVI according to the latest research, of which the above most aptly confirms the current research position.

- ↑ a b c d e f g cf. Roger Matthews: The early prehistory of Mesopotamia. 50,000 - 4,500 BC. Brepols, Turnhout 2000, ISBN 2-503-50729-8 , pp. 57-63

- ↑ cf. Hermann Parzinger: The children of Prometheus. A history of mankind before the invention of writing. 2nd Edition. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-406-66657-5 , pp. 154–157.

- ↑ a b c cf. James Mellaart: The Neolithic of the Near East . Thames & Hudson, London 1975, ISBN 0-500-79003-5 , pp. 135-141.

- ↑ cf. Diana Kirkbride: Umm Dabaghiyah 1971: A Preliminary Report. An Early Ceramic Farming Settlement in Marginal North Central Jazira, Iraq . Contribution in Iraq, Vol. 34, No. 1 (1972), pp. 3-15.

- ↑ The term “baptismal architecture” is often indifferent to the actual “Pisé” building method in the relevant specialist literature. The subsequent, difficult differentiation between the two construction methods in the excavation environment seems to lead to a synonymous use of the terms in the awareness of the technical differences. See: http://www.edition-open-access.de/studies/3/4/index.html#43 , accessed on February 2, 2015

- ↑ cf. Diana Kirkbride: Umm Dabaghiyah 1974: A Fourth Preliminary Report . Contribution in Iraq, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 3-10 (1975).

- ↑ cf. Hans Helbaek: Traces of Plants in the Early Ceramic Site of Umm Dabaghiyah . Contribution in Iraq, Vol. 34, No. 1 (1972), pp. 17-19.

- ↑ cf. Diana Kirkbride: Umm Dabaghiyah: A Trading Outpost? . Contribution in Iraq, Vol. 36, No. 1/2 (1974), pp. 85-92.

- ↑ cf. Sandor Bökönyi: The Fauna of Umm Dabaghiyah: A Preliminary Report . Contribution in Iraq, Vol. 35, No. 1 (1973), pp. 9-11.

- ↑ Matthews points out at this point that a correct identification of the pearls would testify to the first appearance of this material in Mesopotamia.