Halaf culture

| The old Orient | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Timeline based on calibrated C 14 data | |

| Epipalaeolithic | 12000-9500 BC Chr. |

| Kebaria | |

| Natufien | |

| Khiamien | |

| Pre-ceramic Neolithic | 9500-6400 BC Chr. |

| PPNA | 9500-8800 BC Chr. |

| PPNB | 8800-7000 BC Chr. |

| PPNC | 7000-6400 BC Chr. |

| Ceramic Neolithic | 6400-5800 BC Chr. |

| Umm Dabaghiyah culture | 6000-5800 BC Chr. |

| Hassuna culture | 5800-5260 BC Chr. |

| Samarra culture | 5500-5000 BC Chr. |

| Transition to the Chalcolithic | 5800-4500 BC Chr. |

| Halaf culture | 5500-5000 BC Chr. |

| Chalcolithic | 4500-3600 BC Chr. |

| Obed time | 5000-4000 BC Chr. |

| Uruk time | 4000-3100 / 3000 BC Chr. |

| Early Bronze Age | 3000-2000 BC Chr. |

| Jemdet Nasr time | 3000-2800 BC Chr. |

| Early dynasty | 2900 / 2800-2340 BC Chr. |

| Battery life | 2340-2200 BC Chr. |

| New Sumerian / Ur-III period | 2340-2000 BC Chr. |

| Middle Bronze Age | 2000-1550 BC Chr. |

| Isin Larsa Period / Ancient Assyrian Period | 2000–1800 BC Chr. |

| Old Babylonian time | 1800–1595 BC Chr. |

| Late Bronze Age | 1550-1150 BC Chr. |

| Checkout time | 1580-1200 BC Chr. |

| Central Assyrian Period | 1400-1000 BC Chr. |

| Iron age | 1150-600 BC Chr. |

| Isin II time | 1160-1026 BC Chr. |

| Neo-Assyrian time | 1000-600 BC Chr. |

| Neo-Babylonian Period | 1025-627 BC Chr. |

| Late Babylonian Period | 626-539 BC Chr. |

| Achaemenid period | 539-330 BC Chr. |

| Years according to the middle chronology (rounded) | |

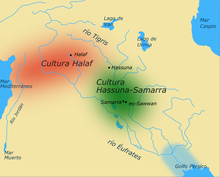

The Halaf culture was a Chalcolithic culture found in northern Mesopotamia , in Syria , in parts of Turkey and as far as the border with Iran and beyond. It flourished from about 5900-5000 BC. BC (other studies date the culture from around 5200 to 4500 BC) The name-giving site is Tell Halaf in Syria. Other important sites are Tell Arpachiyah and Yarim Tepe (both in Iraq ). In terms of its extent, it was one of the most extensive cultures of this time, of which many other sites are known. However, many have hardly been studied.

Dating

The relative chronology of the Halaf culture is established through its pottery. A stable chronology has not yet been established, as it is difficult to distinguish regional differences from temporal differences. First, a classic tripartite division into early, middle and late Halaf period was made, which was later supplemented by a subsequent Halaf- Obed transition phase . This chronology is widely used, but is based on a very small amount of data. Alternatively, there is a division into Halaf Ia, Halaf Ib, Halaf IIa and Halaf IIb. Here Halaf Ia corresponds to an epoch sometimes called the Proto-Halaf period before the early Halaf period. The following subdivisions largely coincide with early, middle and late Halaf times. Both concepts appear in the specialist literature.

Another difficulty is the name of the epoch. The Halaf period is sometimes called the Chalcolithic and sometimes the Neolithic. This is because the beginning of the Chalcolithic period in Mesopotamia is equated with the appearance of painted ceramics. So here the Halaf culture is Chalcolithic. In the Levant, however, the Chalcolithic era only began with the first reliable metalworking. Here the Halaf period belongs to the late Neolithic.

The absolute chronology is dated using C14 samples . The Halaf period begins around 5800 BC. And ends between 5500 and 5000 BC. While the emergence of the Halaf period can be dated relatively precisely across many sites, there are almost no contexts that can be well dated for the transition to the Ubeid culture. What is certain is that the Ubeid culture was 5000 BC. Is fully established. The “classical” Halaf culture cannot be dated any closer than to the period between 5700 and 5500/5000 BC. Chr.

distribution

The core area of the Halaf culture is in the headwaters of the Euphrates and Tigris . However, it extends further south to northern Syria and Iraq.

The Halaf culture developed relatively simultaneously across the entire range from local Neolithic cultures. This is concluded from the distribution of Proto-Halaf pottery, which was found throughout the distribution area. An older interpretation was based on an origin in northern Syria. This interpretation can be traced back to a picture of the distribution of Proto-Halaf pottery that was still incomplete at the time.

In southeastern Turkey are the localities Domuztepe, Çavı Talası, Yunus Höyük , Fıstıklı Höyük , Kazane, Girikihacıyan, Sakçagözü and Boztepe. In northern Syria, the sites of Tell Halaf , Shams ed-Din, Tell Sabi Abyad , Umm Qseir, Tell Aqab and Chagar Bazar belong to the Halaf culture. Yarim Tepe, Tappa Gaura , Tell Arpachiyah and Banahilk are found in northern Iraq .

Characteristics

Ceramics

The Halaf culture today is mainly characterized by its ceramics. The pottery can be roughly divided into fine, richly decorated and coarse, undecorated ceramics. Unadorned pottery makes up a large part of the pottery inventory, but is not specific enough to define Halaf culture. The fine, ornate ceramic is red with black paint. Motifs are geometric patterns as well as stylized people and animals. The older vessels are usually only decorated geometrically. Human and animal motifs only appear in the younger vessels, which were then sometimes even painted with white paint, i.e. are three-colored. Rather the exception are anthropomorphic vessels, such as the female vessel in Yarim Tepe II.

It is assumed that both the naturalistically depicted animals and people, as well as the abstract geometric patterns had a symbolic character and possibly told myths and stories.

seal

The seals are stamp seals made of stone or clay with geometric patterns or symbols. At some sites like Arpachiyeh they appear more frequently and at others hardly at all. They are an indication of management and administration.

Figurines

There are both zoomorphic and stylized human figurines made of clay. The portrayal of people is mostly stylized women with accentuated gender characteristics.

architecture

The settlements of the Halaf culture consisted of round free-standing huts, which are also called tholoi. They have a diameter of three to seven meters and consist of adobe bricks and rammed earth as well as stones. Rectangular small-scale buildings are often found near the tholoi. They are usually interpreted as storage buildings because of their small chambers. The houses formed small villages barely an acre in size. Only a few settlements appear to have been more than 10 hectares in size and these may have been regional centers.

Burials

Little is known about the burial customs of the Halaf culture, but they appear to be inconsistent. In Yarim Tepe , grave shafts were found with a small side chamber in which the corpse was deposited. In Domuztepe , between 35 and 40 people were buried in the so-called death pit . Sometimes their heads were removed and buried individually.

Subsistence

On the one hand arable farming with species such as einkorn , emmer and hexaploid wheat is attested as subsistence farming . On the other hand, there is also evidence of pastoralism with sheep, goats, pigs and dogs. The subsistence strategies differed from location to location. While arable farming could be carried out all year round in regions with high rainfall, sites in areas with low rainfall were more flexible. In addition to seasonal agriculture, hunting and pastoral nomadism were also practiced.

Notes and individual references

- ↑ in the Levant

- ↑ a b c d in southern Mesopotamia

- ↑ a b c in northern Mesopotamia

- ↑ on chronology: Matthews: The early prehistory of Mesopotamia , p. 108.

- ^ Davidson: Regional Variation within the Halaf Ceramic Tradition. Edinburgh 1977.

- ^ Campbell: Culture, Chronology and Change in the Later Neolithic of North Mesopotamia. Edinburgh 1992.

- ↑ Copeland & Hours: The Halafian, there Predecessors and there Contemporaries in Northern Syria and the Levant. 1987, p. 403.

- ↑ Campbell: Rethinking Halaf Chronologies. 2007, pp. 127-132.

- ^ Roger Matthews: The early prehistory of Mesopotamia, 500,000 to 4,500 BC Brepols, Turnhout 2000, p. 108.

- ^ Campbell: The Halaf Period in Iraq: Old Sites and New. Pp. 182-183.

- ↑ a b c d Castro Gressner: A Short Overview of the halaf Phenomenon. 2011, pp. 779-780.

- ↑ Merpert & Muncheav: The Earliest Levels at Yarim Tepe I and Yarim Tepe II in Northern Iraq. 1987, p. 27.

- ↑ Campbell: Understanding Symbols: Putting Meaning into the painted Pottery of Prehistoric northern Mesopotamia. 2010.

- ↑ a b Matthews: The early prehistory of Mesopotamia. 2000, p. 108.

- ↑ Carter, Campbell & Gould: Elusive Complexity: New Data from late Halaf Domuztepe in South Central Turkey. 2003, pp. 120-128.

- ↑ McCorriston: The Halaf Environment and Human Activities in the Khabur drainage, Syria. Pp. 328-330.

literature

- Stuart Campbell : Culture, Chronology and Change in the Later Neolithic of North Mesopotamia. Unpublished PhD thesis at the University of Edinburgh. Edinburgh 1992.

- Stuart Campbell: The Halaf Period in Iraq: Old Sites and New . In: The Biblical Archaeologist. Vol. 55, no. 4, 1992, pp. 182-187.

- Stuart Campbell: Rethinking Halaf Chronologies . In: Paléorient. Vol. 33, No. 1, 2007, 103-136.

- Stuart Campbell: Understanding Symbols: Putting Meaning into the painted Pottery of Prehistoric northern Mesopotamia . In: Diane Bolger, Louise C. Maguire (Eds.): Dévelopment of Pre-State Communities in the Ancient Near East. 2010, pp. 147–155.

- Elizabeth Carter, Stuart Campbell, Suelten Gauld: Elusiv Complexity: New Data from late Halaf Domuztepe in South Central Turkey . In: Paléorient. Vol 29, No. 2. 2003, pp. 117-133.

- Gabriela Castro Gressner: A Brief Overview of the Halaf Tradition. In: Gregory McMahon, Sharon Steadman (Eds.): The Oxfordhandbook of Ancient Anatolia (10,000 - 323 BCE). 2011, pp. 777-795.

- Lorraine Copeland , Francis Hours: The Halafian, there predecsessors and there contemporaries in northern syria and the Levant: Relative and Absolut Chronology. In: Olivier Aurenche, Jacques Evin, Francis Hours (Eds.): Chronologies du Proche Orient - Chronologies of the Near East. Relative Chronologies and Absolut Chronology 16,000-4,000 BP BAR, Oxford 1987, pp. 401-426.

- Davidson: Regional Variation within the Halaf Ceramic Tradition. Unpublished PhD thesis at the University of Edinburgh. Edinburgh 1977.

- Dietz-Otto Edzard (Hrsg.): Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Aräologie (RLA). Vol. 4. de Gruyter, Berlin 1975, pp. 55-59.

- Roger Matthews : The early prehistory of Mesopotamia, 5000,000 to 4,500 bc (= Subartu. V). Brepols, 2000, ISBN 2-503-50729-8 , pp. 85-111.

- Joy McCorriston: The Halaf Environment and Human Activities in the Khabur Drainage, Syria. In: Journal of Field Archeology. Vol. 19, No. 3, Fall 1992, pp. 315-333. ( PDF file; 3.31 MB )

- N. Ya. Mepert & RM Munchaev: The Earliest Levels at Yarim Tepe I and Yarim Tepe II in Northern Iraq . In: Iraq. Vol. 49, 1987, pp. 1-36.

- Michael Roaf : World Atlas of Ancient Cultures: Mesopotamia. Christian-Verlag, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-88472-200-X , pp. 49-51.