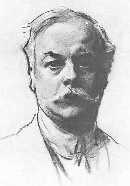

Kenneth Grahame

Kenneth Grahame (born March 8, 1859 in Edinburgh , Scotland , † July 6, 1932 in Pangbourne in Berkshire , England ) was a British writer . His most famous book The Wind in the Willows (1908) is a classic in children's literature . His earlier children's book The Dragon Who Didn't Want to Fight (1898) was filmed by Walt Disney in 1941 as The Dragon Against Will .

Childhood and school days

His father, James Cunningham Grahame, was a lawyer from an old Scottish family and his mother was Bessie (Ingles) Grahame, the daughter of John Ingles of Hilton, Lasswade. Kenneth Grahame, the third child, was born in Edinburgh on March 8, 1859. When Kenneth was barely a year old, his father was given the post of Sheriff of Argyll and the family moved from Edinburgh to Argyll. At first they lived in Ardrishaig while a new house was being built for them. The building took more than two years to complete and the family also lived in Lochgilphead for a few months before moving to their new home in Inveraray.

Her joy in her new home was short-lived. Shortly after Kenneth's fifth birthday, in March 1864, his brother Roland was born, but a few days later his mother fell ill with scarlet fever and died after a brief illness on April 4, 1864. Kenneth himself also contracted the same disease and struggled with it for a few weeks, before he recovered.

During his illness, Granny Inglis, the maternal grandmother, came to Inveraray from Berkshire to look after the child. After Kenneth's recovery it seemed clear that his father, who had succumbed to his old drinking problem, was unable to look after the four children. Helen, Willie, Kenneth and Roland moved to Cookham Dene, Granny Inglis' house "Mount". The Cookham Dene years seem to have been some of Kenneth's happiest years. The "Mount" was a charming old house with an attic and a large garden where the children could play. The majestic Thames was nearby and nurtured a lifelong love of the river and boating in Kenneth, which their uncle, David Ingles, curator of the Church, showed them. But at Christmas 1865, after living there for less than two years, the house's chimney collapsed and the children moved to Fern Hill Cottage in Cranbourne, Berkshire. This was a smaller house a few miles from Cookham Dene and the Thames.

While at Cranbourne, her father made an attempt to overcome his drinking problem and arranged for the children to return to Argyll with him. The children lived in their former home in Inveraray for most of 1866 . In the end, her father fell back into his old habits and left his children, work and Argyll to move to France. It appears that there was no further contact between Cunningham Grahame and his four children for the remaining twenty years of his life.

The children returned to Cranbourne from Argyll and Kenneth lived there until he started at St. Edward's School in Oxford in 1868, at the relatively late age of nine. That was the center of his world for the next nine years. His early years in school were challenging, but by the time he left St. Edward he had won numerous academic and athletic awards - Head Boy, Captain of Rugby XV, Sixth Grade Prize, Divinity Prize, and the Latin Prose Prize.

Director of the Bank of England

His desire for further education at the University of Oxford was thwarted by his stingy uncle, John Grahame, who acted as his guardian. Between 1875 and 1879 he worked for his uncle in an office of the parliamentary agent. During this time Kenneth lived in the "Draycott Lodge" in Fulham with another uncle, Robert Grahame. He had also applied to the Bank of England, headquartered on Threadneedle Street, but had to wait for a position to appear. The Draycott Lodge in Fulham was a long way from the bank, so Kenneth found quarters on Bloomsbury Street. During his early years in London, Kenneth met several leading literary figures and began to circulate in literary circles.

In 1879 he started working for the Bank of England . Again, one could assume that the bank represented everything that Grahame hated most, monotonous and claustrophobic. But it was an extremely strange place in the late 1880s. The staff worked short - very short - hours and the lunch break was long. Several of them held dog fights in the basement. The work was not inappropriately demanding, and as he pursued his career, Grahame began writing easy short stories to pass the time. He published his stories in magazines such as the St. James Gazette , WE Henley's National Observer , which was initially called "The Scots Observer," and the Yellow Book . William Ernest Henley promoted young talent and published works by Thomas Hardy , George Bernard Shaw , Herbert George Wells , Rudyard Kipling and Joseph Conrad . This is how Grahame met these authors.

First literary success

His first book, Pagan Papers , was published in 1893 - a collection of stories and essays on the general subject of escape. For someone so unworldly, Grahame proved to be a surprisingly difficult negotiator with his publishers, earning a much larger than average percentage of the royalty. Despite its title, Pagan Papers had nothing to do with paganism or paganism . Among the essays were some about a family of orphaned children - Edward, Selina, Harold, Charlotte, and an unnamed narrator. These stories about the children and their guardians, called the "Olympics", have autobiographical features. They appeared in the first edition of Pagan Papers, but were excluded from all subsequent editions. Graham's early essays and stories gathered in this volume received praise from Algernon Charles Swinburne .

The following book, "The Golden Age" (1895), a collection of sketches of the lives of five orphaned late Victorian children, was considered the most popular reading of Kaiser Wilhelm II's bedtime on his royal yacht.

Dream Days (1898), the sequel, featured Graham's most famous short story, The Reluctant Dragon. The dragon, a lazy, poem-loving bohemian, wants to be left satisfied, but the villagers want to kill him. Thanks to a clever boy, the peaceful monster manages to keep his life. St. George should thirst for his blood, doesn't want to hurt him. The saint and the dragon give a good performance, "a fun fight," and the dragon collapses as they agreed beforehand.

Both books became so popular that the wind in the willows was a real disappointment to readers at first.

Marriage and birth of his son

In 1897 Grahame met Elspeth Thomson, the 35-year-old daughter of the inventor of the pneumatic tire. They started exchanging letters. These letters were written in baby language. Grahame signed "Dino", and Elspeth, "Minkie". "Darlin Minkie," he wrote in 1899. They were married on July 22nd of that year in Fowey , Cornwall .

Their son, Alastair, was born on May 12, 1900. Alastair was born blind in one eye and with pronounced squint in the other.

On May 7, 1920, Alastair committed suicide

The Robinson incident

At eleven o'clock on the morning of November 24, 1903, a man named George Robinson, who was referred to simply as "a socialist lunatic" in the newspaper bill of what followed, arrived at the Bank of England. There Robinson asked to speak to the governor, Sir Augustus Prevost. Since Prevost had retired a few years earlier, he was asked if he would see the bank secretary, Kenneth Grahame, instead. When Grahame appeared, Robinson walked up to him and held out a rolled-up manuscript. This one was tied with a white ribbon on one end and a black one on the other. He asked Grahame to decide which end to end. After some understandable hesitation, Grahame chose the end with the black ribbon, at which point Robinson drew a pistol and shot him. He fired three rounds, all of which missed Grahame. Several bank employees managed to wrestle Robinson to the ground with the help of the fire department. Strapped in a straitjacket, he was then taken to Broadmoor Hospital , (then called the Asylum) in Crowthorne, Berkshire.

His biggest success

After Kenneth retired from the bank in 1906, the Grahames of Durham Villas moved to an old farmhouse in Blewbury, near Didcot. Life moved at a more relaxed pace and Kenneth had time to complete his book. It was now almost 10 years since he had published a book. A neighbor in Bray, the American named Constance Smedley, convinced Grahame to publish these letters and bedtime stories in a book. Its original title was the "wind in the reeds". But William Butler Yeats had published a collection of poetry of almost the same title, so Grahame changed it to The Wind in the Willows . The book was rejected by every publisher. Eventually, Methuen decided to take it, but only on the basis that they wouldn't pay Grahame an advance.

Published in the fall of 1908, “The Wind in the Willows” received unpleasant reviews almost everywhere. Arthur Ransome judged it a failure through and through - "like a speech made to Hottentots in Chinese". The only reviewer who saw its merits was the writer Arnold Bennett , who rated it "quite successful".

The salvation, however, came from an unexpected source: then-President of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt . Grahame had sent Roosevelt a copy of The Wind in the Willows after Roosevelt had expressed his admiration for his earlier books. Roosevelt loved the book and wrote to the American publishers, Scribners, telling them they had to get it published. Scribners committed to publication and with that the book gained public appreciation.

Grahame died of a cerebral haemorrhage on July 6, 1932 in Pangbourne, England . He is buried in Holywell Cemetery at St. Cross Church in Oxford . His funerary inscription was written by his cousin, the author Anthony Hope , and reads:

"To the beautiful memory of Kenneth Grahame, husband of Elspeth and father of Alastair, who passed the River on the 6th July 1932, leaving childhood and literature through him the more blest for all time." (To the memory of Kenneth Grahame, husband of Elspeth and father of Alastair, who crossed the river on July 6, 1932, and who made childhood and literature all the more happy for all time.)

Works

Grahame initially published short stories in London newspapers such as the St James Gazette . Some of these stories were published in the volume Pagan Papers in 1893 . The Golden Age followed in 1895 and in 1898 the band Traumtage , which contained the story The Dragon Who Didn't Want to Fight . In 1908 he published The Wind in the Willows and in 1916 he was the editor of a poetry collection for children.

- Books

- The wind in the willows. Knesebeck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-86873-423-2 (German first edition)

- The Golden age. German by Emmy Becher. Engelhorn, Stuttgart 1900. Text in the Gutenberg-DE project

- The dragon that didn't want to fight. (The Reluctant Dragon, 1898).

- Dream Days Dream Days .

- Bertie's Escapade (no German translation known).

- Pagan Papers (no German translation known).

- The Headswoman (no German translation known). The only book that wrote for adults.

- The Cambridge Book of Poetry for Children as editor (no German translation known).

- Kenneth Grahame's books in the Internal Archive

- Books by Kenneth Grahame in the Gutenberg e-books project (currently usually not available for users from Germany)

References

Humphrey Carpenter , Mari Prichard: The Oxford Companion to Children's Literature . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, pp. 216-219, ISBN 0-19-211582-0 .

- ^ Cranbourne

- ↑ St Edward's School, Oxford

- ↑ Kenneth Grahame: The Golden Age - Chapter 2 The Olympians Project Gutenberg e-book

- ↑ Scotland's forgotten Inventor - Robert William Thomson

- ↑ Broadmoor Hospital

- ↑ Kenneth Graham, Lost in the Wild Wood by John Preston describes the shooting incident in the Bank on November 24, 1903

literature

Literature on Kenneth Grahame can hardly be found in German. In English, however, there are the following:

- Patrick Chalmers: Kenneth Grahame: life, letters and unpublished work. Methuen, London 1938; Reprint Port Washington, NY [u. a.]: Kennikat Press, 1972, ISBN 0-8046-1560-8

- Eleanor Graham: Kenneth Grahame. HZ Walck, New York 1963.

- Jackie Wullschläger : Inventing wonderland: the lives and fantasies of Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear, JM Barrie, Kenneth Grahame, and AA Milne. Free Press, New York 1995.

- Alison Prince: Kenneth Grahame: An Innocent in the Wild Wood . First edition 1994 - Publisher: Faber and Faber 2009 ISBN 978-0-5712-5370-8

- Peter Green (Grahame's biographer): BEYOND THE WILD WOOD; The World of Kenneth Grahame, Author of the Wind in the Willows; Facts on file; New York; 1983; First American Edition; ISBN 978-0-8719-6740-4

- Matthew Dennison: Eternal boy: the life of Kenneth Grahame , London: Head of Zeus, 2018, ISBN 978-1-78669-773-8

Web links

- Literature by and about Kenneth Grahame in the catalog of the German National Library

- Theater an der Parkaue / Kenneth Grahame biography

- Online Literature / Kenneth Grahame biography and links to online texts by the author

- Kenneth Grahame author page

- Kriegel, Kirsti: Kenneth Grahame. In: Rossipotti Literature Lexicon ; ed. by Annette Kautt;

- Bank of England Photographic Collection from the Archives on Flickr

- Grahame, Kenneth (1859-1932) Author Secretary of the Bank of England - The National Archives

- Collection Level Description: Manuscripts of Kenneth Grahame at the University of Oxford Bodleian Library

- Collection Level Description: Papers of Kenneth Grahame at the University of Oxford Bodleian Library

- Author's spat with the governor of the Bank of England gave us children's classic “Wind in the Willows” By Andrew Levy for the “Daily Mail” 7th October 2008

- Is this the real Mr Toad ? Letters released by the Bank of England shed new light on the inspiration behind Kenneth Grahame's bombastic anti-hero. By Andrew Johnson - The bank's current archivist, John Keyworth, explained that the documents have never been made public because of their personal nature. "It is now 100 years ago (2008) and is part of history," he added.

- Oxford reference - overview Kenneth Grahame

- Works by Kenneth Grahame in the Gutenberg-DE project

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Grahame, Kenneth |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 8, 1859 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Edinburgh , Scotland |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 6, 1932 |

| Place of death | Pangbourne , Berkshire , England |