Scandinavian literature

Scandinavian literature (more precisely: Nordic literature ) is the literature in the languages of the Nordic countries . These include Denmark , Finland , Iceland , Norway and Sweden as well as their autonomous areas of Åland , Faroe Islands and Greenland and Sápmi . The majority of these nations and the area speak North Germanic languages . Although Finnish is spoken in Finland rather than North Germanic, Finnish history and literature have a clear connection with Sweden. Linguistically related to the Finns are the Sami in Sweden, Norway and Finland (as well as Russia).

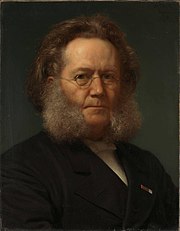

The Scandinavian peoples produced significant and influential literature. The Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen popularized modern realistic drama in Europe, with plays like The Wild Duck and Nora or a Doll's House . The Nobel Prize in Literature was Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson , Selma Lagerlof , Verner von Heidenstam , Karl Adolph Gjellerup , Henrik Pontoppidan , Knut Hamsun , Sigrid Undset , Erik Axel Karlfeldt , Frans Eemil Sillanpää , Johannes V. Jensen , Pär Lagerkvist , Halldór Laxness , Nelly Sachs , Eyvind Johnson , Harry Martinson and Tomas Tranströmer .

In the literatures of Denmark, Norway and Sweden from around 1830 to 1864 a national romantic current (originally shaped by students), Scandinavianism ( Scandinavianism ), was reflected . This was based on Nordic antiquity and aimed politically at the unification of the three empires, whereby it turned against Germany and Russia. This political tendency, which encompassed both liberal and conservative intellectuals with “cultural” or “literary Scandinavianism”, ebbed when Norway and Sweden abandoned Denmark in the war against Prussia and Austria. It revived briefly at the beginning of the 20th century; Finland (with an anti-Russian tendency) was also included at times.

Since the 1970s, feminism supported by equality-oriented politics in the mainland Scandinavian countries has left not only clear thematic traces in literature, but also in language. In addition to sexually neutral articles and job titles, there is also the male nurse in Sweden, without this appearing ridiculous. There are also historical reasons for this.

In the Middle Ages was only in Scandinavia Urnordisch and later Old Norse spoken. The oldest written records in Scandinavia are runic writings on memorial stones and other objects. Some of them contain allusions to Norse mythology and short verses in alliterative form . The best-known example is the artistic Rök rune stone (approx. 800), a memorial to the dead with enigmatic allusions to the legends from the migration period. The oldest poems in the Edda date back to the 9th century, although they are only preserved in manuscripts from the 13th century. They tell the myths and epics of Scandinavia. The scald poetry is similarly preserved, the manuscripts recorded the oral versions of the 9th century.

The Christianization of the 10th century brought Scandinavia into contact with European knowledge, including the Latin alphabet and the Latin language . In the 12th century this bore literary fruits in works such as the Danish Gesta Danorum , a committed historical work by Saxo Grammaticus . The 13th century was considered the Golden Age of Icelandic literature with Snorri Sturluson's Edda and Heimskringla .

Reformation time

Humanism reached the Nordic countries around 1520, followed by the Reformation a short time later . The Kalmar Union , which united the three Nordic kingdoms, broke up as early as 1523 . However, Norway became politically and culturally dependent on Denmark through the introduction of the Reformation and lost its linguistic independence through the adoption of the Bible and the hymn in Danish, while Iceland retained it. The literature of the entire Reformation period was characterized by the publication of religious instruction and utility pamphlets in large numbers; the most important achievements, however, were the translation of the Bible and the hymn in the national language (including Finnish). Towards the end of the 16th century, under the influence of humanism and especially Philipp Melanchthon , neo-Latin literature developed, first in Denmark and a little later in Sweden. However, book printing spread only slowly, so that many books had to be printed in Germany. The development of the national languages was initially hampered by the influence of the Latin and German languages.

Danish literature

The writings of the pre-Reformation period were largely written in Latin. The 16th century brought the Reformation to Denmark and a new period in Danish literature . Leading authors of the time included humanists such as Christiern Pedersen , who translated the New Testament into Danish, and Poul Helgesen , an Erasmus translator and proponent of an enlightened Counter-Reformation . Denmark's first dramas were written in the 16th century, including the works of Hieronymus Justesen Ranchs . The 17th century was an era of renewed interest in Scandinavian roots and antiquity, led by scholars like Ole Worm . Though Lutheran orthodoxy spread, poetry reached a climax in the personal expression of Thomas Kingo's passion hymns . Important Danish authors of the 19th century were Søren Kierkegaard and Hans Christian Andersen . Martin Andersen Nexø, in particular, achieved greater prominence among Danish authors of the 20th century . Karen Blixen grew up in Denmark but wrote her books in English.

Faroese literature

Faroese literature in the traditional sense of the word has actually only developed in the last 100–200 years. This is mainly due to the island location of the Faroe Islands as well as the fact that the Faroese language did not have a standardized writing format until 1890 . Numerous Faroese poems and stories were passed down orally from the Middle Ages . The genres included sagnir (historical material), ævintyr (stories) and kvæði (ballads, often with music and dance). These were only written down in the 19th century and provided the basis for a "belated" but impressive literature. Heðin Brú's fisherman novel “Father and Son on the Road” (German 2015), published in 1940, was the first work in Faroese literature to gain international fame.

Modern authors include Gunnar Hoydal , Oddvør Johansen , who also writes children's books and still writes her books in pencil, and the poet and playwright Joánes Nielsen (* 1953). Several titles by Faroese authors have also been translated into German and English.

Finnish literature

Due to the turbulent history of Finland , which was ruled by Sweden for almost 700 years (until 1809) and Russia for more than 200 years (at times in the 18th century and from 1809 to 1917), the government language (Swedish or Russian ) and that of the educated (mostly Swedish) was different from the vernacular . It was not until 1902 that Finnish became an official language with equal rights. Finnish literature was characterized by its late independence and its greatest works aimed at creating or maintaining a strong Finnish identity. However, authors from the Swedish-speaking minority also often include major historical and national topics such as the Winter War in their work and played an important mediating role in accessing international literature. Literature from the Sami minority in Finland, numbering around 2,500, has only existed since the 1970s.

- For the literature of the Finland Swedes see Finland Swedish literature , for literature in the Sami languages see: Sami literature

Folk poetry

The Finnish language was only developed into a modern literary language about 150 years ago - more precisely, modern language and literature developed together in mutual influence. Folk poetry formed the cornerstone of Finnish literature well into the 20th century. It was created over the course of 1000 years, but it looks very uniform; it is often impossible to tell when it was composed, which is due to the consistent use of alliteration and octosyllabic Trochaic meter. This Finnish folk poetry existed in numerous genres and forms: as lyrical or epic poetry, as didactic, interpretive-evocative or shamanistic magic songs, as hunting songs or original songs ( Historiola ). Their origin was probably mostly on the west coast; later the focus of their tradition shifted to the east to Karelia , where they were cultivated by singers in an artistically demanding form in the 19th century. Another focus of the song tradition was in the east on Lake Ladoga . The Vikings and pre-Reformation times were not able to erase these traditions either, although Christian influences can be seen in the Historiola, which suppress the shamanistic magic song.

National Movement and Romanticism

The first spiritual and educational texts in Finnish were written during the Reformation, but Finnish remained a peasant language that was outlawed in educated circles. At the beginning of the 19th century, under Tsarist rule, but with relative autonomy and supported by the language decree Alexander II, this led to the development of a national movement that was directed against the dominance of Swedish, which was spoken by only one seventh of Finns as their mother tongue, and to upgrade folk poetry.

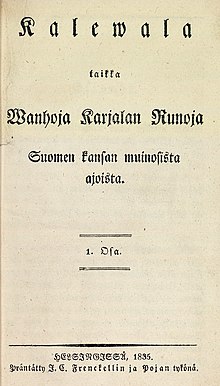

By far the most famous collection of folk poetry is the Kalevala . The work, which is considered the Finnish national epic, was compiled over decades by Elias Lönnrot from orally transmitted chants, mainly from Karelia. First published in 1835 , it quickly became a symbol of Finnish nationalism .

The first novel published in Finnish was The Seven Brothers (1870) by Aleksis Kivi (1834–1872). This work of late romanticism - typical for Finland is an intellectual-historical "delay" compared to Western Europe - is generally considered to be the greatest work in Finnish literature. Kivi also emerged as a poet. Other Romantic authors are the linguist and translator August Ahlqvist (pseudonym: A. Oksanen, 1826–1889) and Karlo Robert Kramsu (1855–1895), who celebrated the peasant uprising of 1596–97 in his bitter ballads. The playwright Kaarlo Bergbom (1843–1906) founded the Finnish National Theater in Helsinki in the 1870s.

The main work of the Swedish-speaking Finnish Romanticism was the verse epic Ensign Stahl (1848/60) by Johan Ludvig Runeberg .

realism

Well-known authors of literary realism before and around the turn of the 20th century were Juhani Aho and the women's rights activist Minna Canth . Thereafter, especially in the poetry of Eino Leino and Volter Kilpi (1874–1939), neo-romantic-archaic movements and in the work of the poet and important translator Otto Manninen (1872–1950) symbolist trends prevailed.

After the First World War , there was a polarization of left and right political forces, which even literary figures could not avoid. This conflict was eclipsed in the 1930s by a bitter linguistic dispute between nationalist Finnish and Swedish intellectuals and students. Frans Eemil Sillanpää was the only Finn to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1939 for his novel Silja, the Maid .

After 1945

After the Second World War , Finnish literature was oriented more towards Anglo-American than German models or Ibsen and Tolstoj. Väinö Linna and Mika Waltari nevertheless published great historical novels, and the epic of history initially retained its place in Finnish literature, although its setting was often the small town; however, since the 1960s and 1970s, the rapid social changes have been reflected in literature, which shed its legacy and addressed current issues such as rural exodus.

Irony and bizarre humor characterize many works of poetry and epic of this time. Arto Paasilinna (* 1942) became internationally popular with 35 humorous novels and audio books.

Since 2000

The epic of history has recently been gaining importance again. The most popular Finnish author at the moment is likely to be Sofi Oksanen (* 1977). Her novels - Purgatory has been translated into almost 40 languages - deal with the horrors of National Socialism and Stalinism in Finland and Estonia. Jari Järvelä (* 1985) and Jari Tervo (* 1959), who was also honored as the author of a detective novel, wrote historical trilogies of novels on the turning points in recent Finnish history. Katja Kettu (*! 978) also became known in Germany through the novel Kätilö (2011; Eng. "Wildauge", 2014) about a German-Finnish love affair during the Winter War.

Book market

After Iceland, Finland has the highest number of books in the world in terms of population, namely around 13-14,000 per year, of which a third are new publications. The country was the guest country of the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2014 . This year around 140 Finnish titles were translated into German and around half as many into Swedish.

Icelandic literature

The Icelandic Sagas ( Icelandic Íslendingasögur ) are prose stories about affairs in Iceland in the 10th and early 11th centuries . They represent the best known and most typical Icelandic literature of the early days. In the late Middle Ages, rímur became the most popular form of poetic expression.

The Reformation marked the beginning of New Icelandic literature. The period from 1550 to 1750 is characterized by translation work and commentaries on the poetry of the scales; however, almost only spiritual texts were printed in the country. The first complete translation of the Bible appeared in 1584. Hymns, psalms and popular epic poems ( rímur ) as well as some travelogues were also written. At the time of the Enlightenment, didactic poems, translations and precursors of modern novels were written since 1750. Romantic poetry spread throughout Iceland around 1830. The high point was the poetry of Jónas Hallgrímsson . Jón Thoroddsen wrote the first modern Icelandic novel .

National romanticism began with a delay. The national patriotic lyric poet Steingrímur Thorsteinsson is considered to be its most important representative . Grímur Thomsen did not publish his poems until the 1880s, shortly before the breakthrough of realism, the most impressive narrator of which was Gestur Pálsson . The neo-romanticism dominated until the 1920s and 1930s.

Gunnar Gunnarsson set himself apart from neo-romanticism with his novels, which were initially written in Danish and later translated; he has been nominated for the Nobel Prize several times. Þórbergur Þórðarson sparked heated controversy with his letter novel Bréf til Láru (1924), which was critical of the Church and capitalism . The leading role in Icelandic literature has been taken over by Halldór Laxness since the 1930s, with an eye for social issues trained by a stay in the USA during the Great Depression. In the 1940s and 1950s he worked on historical material and developed his own narrative style, which was trained at Sagaprosa and presented itself objectively, and received the World Peace Prize in 1953 and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1955. In the 1970s he experimented with new narrative forms, but retained the socially critical impetus. Few prose writers could hold their own alongside him. The important poet and representative of the generation of the atómskáldin ("atomic poet ") Steinn Steinarr changed from communist to nihilist .

In the mid-1960s, a new generation of modernist prose writers, headed by Guðbergur Bergsson , spoke up . The feminist Svava Jakobsdóttir is considered to be the most famous writer and theater pioneer in Iceland. The massive social change since 1980 has produced a literature on childhood and youth in old proletarian, but superficially Americanized Reykjavík of the 1950s and 1960s, the best-known representatives of which are Einar Kárason and Pétur Gunnarsson . Since 1985 women authors like Vigdís Grímsdóttir have played an increasingly important role in Icelandic literary life.

Norwegian literature

One can only speak of an independent Norwegian literature since the 18th century, when it broke away from Danish-language literature. The Norwegian royal chronicles in the Old Norse language such as the Ágrip af Nóregs konunga sögum and the Heimskringla were mostly written by Icelanders outside the country. This does not apply to the Fagrskinna , which was made around 1220, but it is also believed to have come from an Icelander. The following period, from the 14th to the middle of the 18th century, when Norway was ruled by Denmark, is considered the dark age of Norwegian literature , although Norwegian-born authors such as Peder Claussøn Friis and Ludvig Holberg contributed to the general Danish-Norwegian literature and expressed regional characteristics.

Enlightenment, sensitivity, romance

In the 18th century, in addition to the German, French and English influences on the bourgeois-urban culture of Norway, u. a. through the work of Edward Young (1683–1765). Especially in opposition to the cultural preponderance of Germans, the Norwegians developed a stronger national feeling. In 1760 "Det Trondhjemska lærdeSelskab" was formed in Trondheim , a society of scholars that was still influenced by German philosophy, which in 1767 merged into "Det Kongelige Norske Videnskabers Selskab". The historian Gerhard Schøning (1722–1780) left Trondheim in 1765 and went to Denmark. In his main work, Norges Riiges Historie (3 volumes, 1771–81), he defended the rights of the free Germanic peasant against absolutism. Similarly, the pre-romantic Hans Bull (1739–1783) idealized rural life in the mountains with his poem Landmandens Lyksalighed (1771; “Glückseligkeitdes Landmanns”). These mountains, which distinguish Norway from flat or at best hilly Denmark, became the epitome of the pursuit of freedom. But most of the Norwegian authors worked in Denmark: Johan Nordahl Brun (1745–1816) wrote tragedies in the French style, Niels Krog Bredal (1732–1778) brought up Nordic material to the music of Giuseppe Sarti for the first time in his opera Gram og Signe in 1756 Copenhagen stage. Only with the rise of nationalism and the struggle for independence at the beginning of the 19th century, which had been directed against the union with Sweden since 1814, did national literature flourish. The playwright and popular enlightener Henrik Wergeland was the most influential author of this period of the Late Enlightenment and Romanticism.

The Big Four: Psychological Realism and Naturalism

In the second half of the 19th century, the playwright Henrik Ibsen and the realistic narrator and playwright Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson gave Norway an influential place in Western European literature. In Et Dukkehjem (“Nora or A Doll's House”) from 1879, Ibsen realized his ideas on the emancipation of women with a radicalism unknown at the time: the main character Nora leaves her doll's house in order to realize herself. Alexander Kielland made the class differences the topic, castigated the bigotry of the bourgeoisie in his sharply contrasting and sometimes satirical works and thus influenced Thomas Mann . The novelist and playwright Jonas Lie completes the quartet of the "Big Four" of Norwegian literature.

Johan Bojer designed the life of fishermen, sailors and emigrants in a naturalistic way. Another representative of naturalism, also read in Germany, was Arne Garborg . The naturalistic works also include the marriage, family and psychiatry novels by Amalie Skram . The generational novel type, such as Skram's four-volume work Hellemyrsfolket , has played a major role in Norwegian literature since the 19th century, as have the topics of social advancement and social milieu.

Many Norwegian authors came from the simplest of backgrounds, and autobiographical elements are often found in their works. This also applies to the work of Hans E. Kinck , who wrote poetry in addition to novels and short stories. It can be assigned to the neo-romanticism and shows expressionistic influences.

1900-1970

The best-known Norwegian writers of the 20th century include the Nobel Prize winners Knut Hamsun , whose first work “ Hunger ” already established his world fame, and Sigrid Undset . Undset's historical and psychological novels are hardly read today, while Hamsun's anti-bourgeois, autobiographical works were widely received in Germany. Before the Second World War, the popular novels of the country-loving, conservative author Trygve Gulbranssen (the Björndal trilogy ) became world famous. Gunnar Larsen's novels are stylistically influenced by Ernest Hemingway .

After 1945, the history of the occupation and collaboration was dealt with. Hamsun's cooperation with the National Socialists and his lack of insight after the war raised many questions. Kåre Holt's novel Hevnen hører mig til (“Revenge is mine”, 1953) is about the German occupation. Furthermore, psychological and historical novels and stories were written in a factual style, which were often associated with criticism of the bourgeoisie and puritanism. Holt wrote two historical novel trilogies about the labor movement and King Sverre . Tarjei Vesaas (1897–1970) wrote after 1945 his early works of the 1920s and 1930s, which were partly in the realistic tradition and partly influenced by Expressionism, in plays and novels in a lyrical tone with symbolistic and allegorical elements on Nynorsk , which is on the west coast and in the fjord region is common.

Since 1970: social criticism and feminism

Norwegian literature has become politicized since the 1970s. The women's movement - represented literarily by Bjørg Vik (1935–2018) and Liv Køltzow (* 1945) -, environmental protection and social criticism found their expression in it, only to give way to a new inwardness since the 1980s. Bjørg Vik's collection of short stories, Kvinneakvariet (192, German: “Das Frauenaquarium”, 1979), which is based on the precise observation of everyday processes, illustrates how the social framework with its static role models limits the personal development of women. But the life situation depends mainly on their social origin. Women from a proletarian milieu often break under the double burden. Vik later distanced himself from parts of the women's movement; it avoids the schematism of social realism. Also Dag Solstad (* 1941) developed after beginnings as a political protest author to author successful psychological novels. The award-winning Roy Jacobsen (* 1954) wrote 17 novels and numerous short stories in 35 years, some with psychological, but often historical and political topics from the saga to the winter war . His family novel Seierherrene ("Die Sieger", 1991) is about social advancement from the simplest rural conditions to the establishment of a company by the academically educated youngest generation over the course of 80 years. Also Kjartan Fløgstad (* 1944), who himself worked as an industrial worker and sailor and then studied architecture, is concerned with the processes of modernization of Norwegian society from a social science perspective reflected. He writes poetry, realistic, partly baroque novels, non-fiction prose and documentaries. His work Kron og mynt ("Krone und Münze", 1998) was referred to as the Norwegian Ulysses . Fløgstad strongly criticized the behavior of the Norwegian writers and their association during the time of the German occupation.

Since 1990: Postmodernism

As a postmodern author, Jostein Gaarder (* 1952) became known to young and adult readers with his successful novels Das Kartengeheimnis (German 1995) and Sofies Welt (German 1993). His novel about the history of philosophy marked the beginning of a new wave of success for Scandinavian literature in Germany. Pieces by the postmodern poet, novelist and playwright John Fosse (* 1959) have also been played on German stages. Today he lives in Austria. Karl Ove Knausgård (* 1968) wrote a much-discussed six-volume autobiography (Min Kamp ). These books were also distributed in the English and German-speaking countries. Erik Fosnes Hansen (* 1965) became known in Germany for his Titanic novel Choral am Ende der Reise (2007). Lars Lenth (* 1966) should be mentioned among the crime writers .

present

Since the 2010s, novels by Norwegian women authors have been quite successful. These include Nina Lykke (* 1965), who also writes short stories, Tiril Broch Aakre (* 1976), Helga Flatland (* 1984), Linn Ullmann and Gine Cornelia Pedersen (* 1986), who have each written several novels. Maja Lunde (* 1975) became known in Germany for The History of Bees (2015, German 2017), which was also published in 30 other countries; she also wrote scripts and children's books. Per Petterson (* 1952) writes marriage, family and youth novels that have also been published in Germany (“Is already in order”, 2011). “Stealing Horses” (2006), a father-son novel, became a world bestseller.

Literature prizes and book market

So far, three Norwegians have received the Nobel Prize for Literature : Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1903), Knut Hamsun (1920) and Sigrid Undset (1928). The Nordic Council's Literature Prize is particularly well regarded in Norway (and Iceland). Jürgen Hiller attributes this to the middle position of the Norwegian language among the Scandinavian languages, which means that literature from the other Scandinavian countries is increasingly received, sometimes also in the original language.

In 2019, Norway was the guest country at the Frankfurt Book Fair . On average, every Norwegian reads 15 titles a year, which is a lot in a global comparison. However, a decrease of almost 50 percent is recorded in the age group of 25 to 40 year olds.

Swedish literature

The Swedish literature experienced in the Middle Ages a first climax with the holy Birgitta . As in other Scandinavian countries, the translation of the Bible at the time of the Reformation (the Wasa Bible ) was of great importance. August Strindberg and Selma Lagerlöf worked at the beginning of the 20th century . Astrid Lindgren became known as a children's book author . Swedish authors of detective novels are Liza Marklund , Henning Mankell , Stieg Larsson and the couple Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö , who created the character of Inspector Beck . Sweden ranks fifth in the list of countries with the highest number of Nobel Prize winners for literature .

Sami literature

The first translations of the traditional joik , a chant that developed from the shaman chants of reindeer herders, date back to the late 17th century. The first book printed in the Sami language , a translation of Martin Luther's catechism, appeared in Copenhagen in 1728.

The Sami pastor and poet from Sweden Anders Fjellner collected folk poems in the 19th century and integrated them in his epic The Sons of the Sun , which he hoped would have an effect similar to that of Kalevala for Finnish identity. However, the development of the written language was hampered by the fragmentation of the language variants and settlement areas; only North Sami was spread as a written language, above all by the Norwegian Sami and language pioneer Johan Turi (1854-1936), who wrote an exact description of the way of life of nomadic reindeer herders in North Sami ( Muitalus sámiid birra , Copenhagen 1919; Eng .: “Story of the life of the rag” 2012) has been published. North Sami became a kind of lingua franca in the Sami settlement area. Poetry dominated literature: the Norwegian Peder Jalvi (1888–1916) wrote impressionistic natural poems in the North Sami language. Paulus Utsi (1918–1975), who was also born in Norway and later lived in Sweden, dealt with the destruction of the landscape in his poems. He mastered various Sami dialects, made a contribution to the development of the written language and also worked as a singer. The Finnish seed Hans Aslak Guttorm (1907–1992) addressed the difficult search for a mother tongue in his collection of poems and novels, Koccam spalli (“Refreshing Wind”, 1940), one of the few books that were published between 1925 and 1970 in the Sami language .

Due to the colonization of the traditional Sami settlement areas, there was resettlement and discrimination against the Sami language and its speakers. Only the Norwegian philologist Just Knud Quigstad (1853–1957) found Sami fairy tales and stories to be worth collecting and published them in translated form between the 1920s and 1950s.

Until the Second World War, Sámi children were often brought up in boarding schools, where they were not allowed to use their mother tongue. This ban was in place until the 1960s. As soon as it was lifted, new risks arose for the preservation of the language and the traditional ways of life due to the emigration of the young and the desires of the mining industry. In the 1970s, the focus of Sami literature production shifted to Finland. The poet and novelist Hans Aslak Guttorm began to publish again after finishing his work as a teacher in the 1980s. Kirsti Paltto (* 1947), who lives in northernmost Finland, describes the losses her people suffered in the war in the traditional Sami narrative style. Her novel “Signs of Destruction” was the first book to be translated from Sami into German in 1997. Also Olavi Paltto discussed migration and uprooting. Rauni Magga Lukkari became known for her poetry and as a playwright, Nils-Aslak Valkeapää (* 1943) also for his poetry, but also as a musician and photographer. It is the only seed to have received the Nordic Council's Literature Prize in 1991.

With only around 35,000 Sami-speaking people, the book market for Sami-language texts is very small. Despite considerable translation problems and many language variants, some works have recently been translated into Finnish, Swedish, Norwegian, English and German. Sami texts are also produced in Russia and printed in Cyrillic script; The most important author here was Alexandra Andrejewna Antonowa , who in the years after 1970 developed the Kildin-Sami written language for the Sami group of only a few hundred speakers on the Kola Peninsula.

Literary prizes

Nordic Council Literature Prize

The Nordic Council Literature Prize is awarded by a Scandinavian jury for literature (novel, drama, poetry, short story or essay) written in a Scandinavian language. The jury is appointed by the council and consists of 10 members.

- Two danes,

- Two Finns (1 Finnish-speaking, 1 Swedish-speaking)

- Two Icelanders

- Two Norwegians and

- Two Swedes.

National prices

Denmark

Faroe Islands

Finland

Norway

- Bastianpris (for translations)

- Bokhandelens forfatterstipend (author's grant from the book trade)

- Bragepris

- Norwegian Critics' Prize for Literature

- Halldis Moren Vesaas Prize

- NBU awards

- Norwegian Thorleif Dahl Memorial Award of the Academy

- Norwegian Academy for Literature and Freedom of Expression

- Rivertonpris (for crime fiction)

- Sultpris (award for young authors named after the first work by Knut Hamsun)

- Tarjei Vesaas' debutantpris (for first-time authors)

Sweden

- Astrid Lindgren Memorial Prize

- Astrid Lindgren Prize

- Nils Holgersson badge

- Selma Lagerlöf Literature Prize

- Svenska Dagbladet Literature Prize

- August Strindberg Prize

- Listener literature award Sveriges Radio

- Samfounds De Nio Prize

See also

literature

- Selected by Karin Hoff and Lutz Rühling : Scandinavian literature. 19th century . Kindler compact series. JB Metzler Verlag, 2016, ISBN 978-3-476-04065-7 .

- Johanna Domokos, Michael Rießler , Christine Schlosser (eds.): Words disappear / fly / to the blue light: Sami poetry from yoik to rap (= Samica . Band 4 ). Scandinavian seminar of the Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg , Freiburg 2019, ISBN 978-3-9816835-3-0 .

- Fritz Paul (Ed.): Basic features of the newer Scandinavian literatures. Darmstadt 1982 (2nd edition 1991).

- Jürg Glauser : Iceland - a literary history . JB Metzler Verlag, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-476-02321-6 .

- Hubert Seelow : Die Neuisländische Literatur in: Kindlers new Literature Lexicon, Vol. 20, Munich 1996, pp. 116-119.

- Turid Sigurdardottir: The Faroese Literature , ibid., Pp. 120-124.

- Wolfgang Butt : The Danish Literature , ibid., Pp. 125-131.

- Wolfgang Butt: The Swedish literature , ibid., Pp. 132-138.

- Walter Baumgarten: The Norwegian literature , ibid., Pp. 139–147.

- Harald Gaski: Die Samische Literatur , ibid., Pp. 348–351.

- Hans Fromm : The Finnish literature , ibid., Pp. 352–355.

- Elisabeth Böker: Scandinavian bestsellers on the German book market. Analysis of the current literature boom. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann 2018, ISBN 978-3-8260-6464-7

- Harald L. Tveterås: History of the book trade in Norway. Translated from Norwegian by Eckart Klaus Roloff . Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 1992, ISBN 3-447-03172-7 .

Web links

- Link catalog on Scandinavian literature at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

Remarks

- ↑ In the geographical sense, Scandinavia only includes the Scandinavian peninsula; Linguists and cultural geographers also include Denmark. See also the commentary from the Finnish Embassy in Germany (2005): [1]

- ^ Wilhelm Friese : From the Reformation to the Baroque. In: Fritz Paul (Ed.): Basic features of the newer Scandinavian literatures. Darmstadt 1982, p. 2 ff.

- ↑ Literature of the Faroe Islands , accessed September 30, 2015.

- ↑ Otto Oberholzer: Enlightenment, Classicism, Pre-Romanticism. In: Fritz Paul (Ed.), 1982, p. 58 ff.

- ↑ K. Sk.-KLL: Kvinneakquariet. In: Kindler's new literary lexicon. Vol. 17, Munich 1996, p. 158 f.

- ^ Elisabeth Böker: Scandinavian bestsellers on the German book market. Analysis of the current literature boom . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2018, ISBN 978-3-8260-6464-7 , p. 133-140; 314-315 .

- ↑ Jürgen Hiller: The Literature Prize of the Nordic Council: Tendencies - Practices - Strategies - Constructions. Munich 2019, p. 103.

- ↑ Holger Heimann: Read as "Digital Detox" sell on dlf.de, August 3, 2019.

- ↑ On the Sami literary history cf. Christine Schlosser: Afterword by the translator . In: Johanna Domokos, Michael Rießler, Christine Schlosser (eds.): Words disappear / fly / to the blue light. Sami poetry from yoik to rap (= Samica . Band 4 ). Scandinavian Seminar of the Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg , Freiburg 2019, ISBN 978-3-9816835-3-0 , p. 425-446 . ; Harald Gaski: The Sami literature , in: Kindlers new literature lexicon , vol. 20. Munich 1996, pp. 348–351; Veli-Pekka Lehtola: From animal fur to borderless shores: To the history of Lappish literature , in: Trajekt 5 (1985), pp. 24-35.

- ↑ Book and author information on the website of the Persona Verlag

- ↑ About the Nordic Council's Literature Prize ( Memento of August 21, 2007 in the Internet Archive )