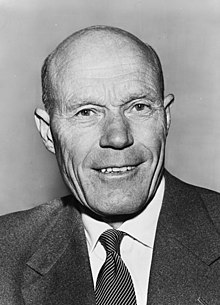

Tarjei Vesaas

Tarjei Vesaas (born August 20, 1897 in Vinje , Telemark province , † March 15, 1970 in Oslo ) was a Norwegian novelist , poet and playwright . In his home country he is counted among the most important authors of the 20th century. He was nominated several times for the Nobel Prize for Literature , but without receiving the award. It is also considered a classic of the Nynorsk literature.

Life

Tarjei Vesaas grew up on a farm in Telemark. After graduating from school and spending several months at the adult education center in Voss , which was run as a boarding school , he lived between 1918 and 1919 for a good six months in Kristiania , today's Oslo, where he was very interested in the theater . From 1925 to 1933 he made numerous trips to Europe; he lived in Paris , London and Munich , among others . Throughout his life he suffered from the feeling of guilt for not having taken over his own family farm contrary to his father's wishes. At times he isolated himself from any society, even in the densely populated large European cities, whose "grinder" fascinated and terrified him. Vesaas read a lot, initially mainly works by Rudyard Kipling , Knut Hamsun and Selma Lagerlöf , and later other great European modern authors . After he married the poet Halldis Moren in 1934 , he moved into the Midtbø farm in his home commune Vinje with her and lived there until shortly before his death.

Early work

His first books, which began to appear from 1923, are primarily romantic and lyrical. His breakthrough came with the much more realistic and tense novel Dei svarte hestane ( The Black Horses ), which he published in 1928.

As a young man, World War I made a big impression on Vesaas. In his first books, great imminent dangers and the constant threat to the joy of life are recurring motifs. The play Ultimatum (written in 1932, first performed in 1934), influenced by German Expressionism , is about B. from the reactions of young people who expect a devastating outbreak of war. Children, animals and various elements of nature emerge as positive opposing powers in his early work, but they are never idyllic.

In the fall of 1940, Kimen (literally: Der Keim ; German title: Nachtwache ) was his most important work to date. After a violent crime on a small island, the peasant society organized a hunt for the mentally unstable perpetrator, who was ultimately murdered himself. The people on the island, who have driven each other to the act of revenge in a kind of mass hysteria , then each try their own way to ease their conscience. The novel thrives on its suggestive, atmospheric images and for the first time reveals the influence of an allegorical technique that Vesaas was to develop to mastery after the war. As early as 1945, the threatening events in the novel Huset i mørkret ( The House in the Dark ) symbolized the German occupation of Norway, barely covered .

Novels after 1945

After the Second World War , Vesaas developed, according to a formulation by the critic Øystein Rottem, a “modernism with a humanistic face”. Without the need for a big city setting, his books describe processes of alienation , loneliness and a feeling of unreality. However, there is almost always - often only hinted at - a vital element in his poetry. The tendency towards self-destruction, which can be observed in several figures, is contrasted with vitality; there is a dimension of hope in many works.

The novel Bleikep Klassen (literally: Die Bleiche; German title: Johan Tander ), published in 1946, shows many typical elements of Vesaa's post-war art with a minimum of external plot, a masterfully developed inside view, carefully integrated symbolism and a sometimes lyrical language. The protagonist Johan Tander has become estranged from his wife and is drawn to a young girl who has a relationship with a man who Tander hated. Tander's wife tries to save the marriage (and her husband) by one day writing a sentence on a house wall in large letters: “Nobody cares about Johan Tander.” This initially only leads to new insecurity and open self-hatred developed, but gradually, albeit almost too late, he realizes that his wife acted out of concern for him.

The fearful atmosphere after the bombing of Hiroshima is reflected in the allegorical parable Signalet ( The Signal ) from 1950. In a train station, a group of travelers is waiting for the signal to continue, which, however, is never given. The reasons for the delay are never given. The situation of the strongly existentially charged waiting is reminiscent of the drama of Samuel Beckett , especially of his classic Waiting for Godot , which, however, was only to appear two years after Vesaas' novel.

His novel Fuglane ( The Birds ) from 1957, which is still internationally best known today , describes the outsider Mattis, who has retained a childish naivety, but is perceived as mentally handicapped and laughed at by those around him. He lives apart from society with his sister Hege. One day a strange man named Jørgen appears on the farm and falls in love with Hege; Mattis soon feels no longer noticed by her either. When Jørgen shoots a woodcock - Mattis is particularly drawn to these birds - he intuitively understands that his death is imminent. Indeed, this scene functions as a symbolic announcement of the tragic end. The quiet Mattis, who is familiar with many natural phenomena, has been brought into connection with Vesaas himself, who confirmed in interviews that he wanted to illuminate "the artist's situation" with this figure and, with certain restrictions , had created a self-portrait . The novel was successfully filmed in Poland .

His novel Is-slottet ( The Ice Castle ), also filmed in 1963, tells of two girls on the verge of puberty , of their tender friendship and their separation through death. The shy, parentless Unn, who only recently moved into the area, gets lost in the labyrinth of a frozen waterfall, the eponymous "Ice Castle", and is not found again. The constant memory of her friend increasingly isolates the actually lively Siss from the environment until she finds her way back to life through children of the same age. A strong, central symbol (the ice castle), which can also be read as completely real , holds the book together, which contains the most successful lyrical passages of the entire oeuvre. The critically acclaimed novel was awarded the Nordic Council's coveted literary prize a year later . The sum of money he received was donated by Vesaas for the newly created Tarjei Vesaas Debutant Prize , which has been awarded to the best literary debut of the year to this day .

Short prose and poetry

In addition to his novels, Vesaas' four volumes of short prose enjoyed particularly high esteem from an early age; they are now part of the canon of Norwegian literature. The terse, concise style, the prosalyrian narrative style, the concentrated composition , the technique of suggestion and the symbolic-allegorical exaggeration that is repeatedly brought into play are particularly effective in his short stories . The volume Vindane ( The wind blows as it will ), published in 1952 , was awarded the Venezia Prize for the best European book of the year.

It was not until he was 49 that Vesaas made his debut as a poet. After a traditional first publication (1946), he surprised the public with the volume Leiken og lynet ( Das Spiel und der Blitz ), which has a modernist formal language and is clearly influenced by Edith Södergran and German Expressionism. Many of the poems in this and the other volumes of poetry revolve around the subject of fear, which was particularly virulent shortly after the war. Texts such as Regn i Hiroshima ( Rain in Hiroshima ) are among the reading book classics in Norway today.

Individual evidence

- ↑ See Steinar Gimnes, Ein vinbyggje på tur i Europa. Holdningar til det framande i Tarjei Vesaas' reisebrev frå kontinentet 1926-1933, in: Motskrift , 2004, no . 2, pp. 28–35, here: p. 31

- ↑ Øystein Rottem, Modernisme med humanistisk ansikt, in: Edvard Beyer (ed.), Norges Litteraturhistorie , 8 vol., Vol. 6, Oslo 1995, pp. 142–163, here: p. 145

- ↑ See ibid., P. 153

literature

Primary literature

- Menneskebonn (Human Children ), Roman (1923)

- Sendemann Huskuld (Der Bote Huskuld), novel (1924)

- Guds bustader (God's Apartments), drama (1925)

- Grindegard. Morgons (Grindegard. The Morning), novel (1925)

- Grinde-kveld eller Den gode engelen (Grindekveld or The Good Angel), novel (1926)

- Dei svarte hestane (The Black Horses), novel (1928)

- Klokka i haugen (The Bell in the Hill), short prose (1929)

- Far's journey (father's journey), novel (1930)

- Sigrid Stallbrokk , novel, (1931)

- Dei ukjende mennene (The Unknown Men), novel (1932)

- Sandeltreet (The Sandel Tree ), novel, (1933)

- Ultimatum (Ultimatum), Drama (1934)

- Det store spelet (The Great Game), novel (1934)

- Kvinnor ropar heim (A woman calls home), novel (1935)

- Leiret og hjulet (The clay and the wheel), short prose (1936)

- Hjarta høyrer sine heimlandstonar (Guardian of his life), novel (1938)

- Kimen (Night Watch), Roman (1940)

- Huset i mørkret (The House in the Dark), novel (1945)

- Bleikep Klassen (Johan Tander), Roman (1946)

- Kjeldene (The Sources), Poems (1946)

- Leiken og lynet (The Game and the Lightning), poems (1947)

- Morgonvinden (The Morning Wind), drama (1947)

- Tårnet (The Tower), novel (1948)

- Lykka for ferdesmenn (the happiness of travelers), poems (1949)

- Signalet (The Signal), Roman (1950)

- Vindane (The wind blows as it will), short prose (1952)

- Løynde eldars land (Land of Hidden Fires), poems (1953)

- 21 år (21 years), Drama (1953)

- Avskil med treet (Farewell to the Tree), drama (1953)

- Vårnatt (Spring Night), novel (1954)

- Ver ny, vår draum ( Become new, our dream), poems (1956)

- Fuglane (The Birds), Novel (1957)

- Ein vakker dag (A beautiful day), short prose (1959)

- Brannen (The Fire), Roman (1961)

- Is-slottet (The Ice Castle), novel (1963)

- Bruene (Three People), Roman (1966)

- Båten om kvelden (Boat in the Evening), novel, (1968)

- Liv ved straumen (Life by the river), poems (posthumously 1970)

- Huset og fuglen (The House and the Bird), texts and images 1919–1969 (posthumously 1971)

Secondary literature

- Walter Baumgartner , Tarjei Vesaas. An aesthetic biography , Neumünster: Wachholtz, 1976. ISBN 3-529-03305-7

- Kenneth G. Chapman, Tarjei Vesaas , New York: Twayne, 1970.

- Steinar Gimnes (ed.), Kunstens fortrolling. Nylesingar i Tarjei Vesaas' forfattarskap , Oslo: LNU / Cappelen, 2002. ISBN 82-02-19659-0

- Frode Hermundsgård, Child of the Earth. Tarjei Vesaas and Scandinavian Primitivism , New York: Greenwood, 1989. ISBN 0-313-25944-5

- Øystein Rottem, Modernisme med humanistisk ansikt, in: Edvard Beyer (ed.), Norges Litteraturhistorie , 8 Vols., Vol. 6, Oslo 1995, pp. 142–163.

- Olav Vesaas, Løynde land. Ei bok om Tarjei Vesaas , Oslo: Cappelen, 1995. ISBN 82-02-12939-7

Film adaptations

- 1951 - Dei svarte hestane - Director: Hans Jacob Nilsen / Sigval Maartmann-Moe

- 1968 - Zywot Mateusza (Fuglane) - Director: Witold Leszczyński

- 1974 - Kimen - Director: Erik Solbakken

- 1976 Vårnatt - Director: Erik Solbakken

- 1987 - Is-slottet - Director: Per Blom

See also

Web links

- Literature by and about Tarjei Vesaas in the catalog of the German National Library

- Tarjei Vesaas in the Internet Movie Database (English)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Vesaas, Tarjei |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Norwegian novelist, poet and playwright |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 20, 1897 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vinje , Telemark Province |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 15, 1970 |

| Place of death | Oslo |