Elias Lönnrot

Elias Lönnrot [ ˈɛlias ˈlœnruːt ] (born April 9, 1802 in Sammatti ; † March 19, 1884 ibid) was a Finnish writer, philologist and doctor. On his travels in Finland and East Karelia he recorded the orally transmitted Finnish folk poetry , on the basis of which he wrote the national epic Kalevala (1835; final version 1849) and the song collection Kanteletar (1840). In doing so, he laid the foundation for Finnish-language literature and the development of a Finnish identity. After the Bible translator Mikael Agricola, he is considered the "second father of the Finnish language". The banknote for 500 Finnish marks , which was currency from 1986 until the introduction of the euro, bears his image.

Life

Youth and Studies

Elias Lönnrot was born on April 9, 1802 in Sammatti, southern Finland, the fourth of seven children of the tailor Frederik Juhana Lönnrot and his wife Ulriika Wahlberg. He spent his childhood in poor conditions. For the family's livelihood he had to help his father with his work and sometimes even beg. Because he showed great talent as a child and learned to read at the age of five, his parents enabled him to go to school despite their poverty. Between 1814 and 1818 he attended the schools of Ekenäs (Tammisaari) and Turku . In the meantime he had to interrupt school for financial reasons. After earning money as a traveling singer, among other things, he was able to continue his education in Porvoo in 1820 , where he passed his Abitur.

In 1822 he began his studies at the Turku Academy . His fellow students included Johan Ludvig Runeberg and Johan Vilhelm Snellman , who would later become the most influential promoters of Finnish culture. In 1827 Lönnrot received a doctorate in philosophy. The title of his dissertation was De Väinämöine, priscorum Fennorum numine ("About Väinämöinen, a deity of the ancient Finns"). The suggestion for the choice of the topic had given him his professor Reinhold von Becker . In the meantime, Lönnrot worked as a private teacher at the home of the medical professor J. A. Törngren in Vesilahti . Törngren and his wife Eva Agatha were important sponsors of Lönnrot and encouraged him to do his philological research.

Elias Lönnrot continued his studies in medicine, probably also under the influence of the physician Törngren. The academy was moved from Turku to Helsinki after the great fire in 1828 and converted into the University of Helsinki . In 1832 Lönnrot received his license to practice medicine with his dissertation Om finnarnes magiska medicin ("On the magical medicine of the Finns").

Collective trips

Through his teacher Reinhold von Becker, Elias Lönnrot came into contact with Finnish folk poetry during his studies. Henrik Gabriel Porthan and Zacharias Topelius the Elder had already laid the foundation for their research . At the same time, the awakening national consciousness and Johann Gottfried von Herder's “Volksgeist” ideas created a heightened interest in recording traditional, orally transmitted songs (also known as “runes”). This task was taken over by Elias Lönnrot. For this purpose he made a total of eleven trips between 1828 and 1844. He covered a total of approximately 20,000 kilometers, mostly on foot, rowing or on skis, under conditions that were sometimes full of privation. In total he collected 65,000 verses of folk poetry on his travels.

Lönnrot made his first trip in 1828 when he had to wait for his studies to continue after the fire in Turku. Between April and September he traveled on foot from the regions of Häme , Savo and North Karelia to the island of Valamo . As a product of this first trip, the travel diary Vandraren ("The Wanderer") and four volumes of poetry with the title Kantele were created .

A collecting trip to East Karelia that began in 1831 ended in Kuusamo when the health authorities ordered him back to southern Finland to help fight a cholera epidemic . After completing his medical degree, Lönnrot traveled to Karelia from July to September 1832 with two fellow students. From Nurmes he crossed the border with Russia and visited the villages of Repola and Akonlahti, where the rune singer Trohkimaińi Soava gave him valuable records.

In 1833 Lönnrot got a job as a district doctor in Kajaani in northern Finland , where he was to practice until 1854. From there he started his fourth and most important collecting trip to East Karelia in the same year. In the village of Vuonninen he met the singers Ontrei Malinen and Vaassila Kieleväinen; the latter inspired Lönnrot to put the collected runes together into a uniform work. In 1834, Lönnrot published the runokokous Väinämöisestä (“Runic collection about Väinämöinen”), a kind of “Proto-Kalevala”, consisting of 5052 verses , in which for the first time the artistic intention was in the foreground instead of a scientific and text-critical discussion.

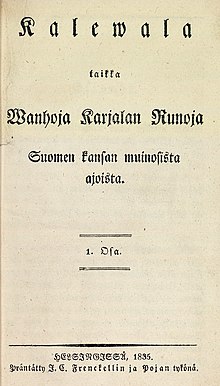

In the same year Lönnrot made another trip from Kajaani and collected songs by Arhippa Perttunen from Latvajärvi, who later became the most important source for the Kalevala . After he had handed in the manuscript for the Kalevala , the sixth journey followed in April 1835, during which he covered 800 kilometers in five weeks. The first edition of the Kalevala appeared in two volumes from 1835 to 1836 under the title Kalewala, taikka Wanhoja Karjalan Runoja Suomen kansan muinoisista ajoista ("Kalevala, or ancient runes of Karelia on ancient times of the Finnish people").

Even after the epic was published, Lönnrot continued his travels. Between September 1836 and May 1837 he undertook a long journey that brought much hardship but hardly any results. After two further trips in the following years, the Kanteletar poetry collection was published in three volumes from 1840 to 1841 .

In Lönnrot's later trips, linguistic interests were in the foreground. From the beginning of 1841 to the end of 1842 he traveled together with the linguist MA Castrén to Lapland , Kola and Arkhangelsk as well as to the Wepsen in East Karelia. His eleventh and last trip took Elias Lönnrot in 1844 to Estonia , where he was elected honorary member of the Estonian Scholarly Society , and to Ingermanland .

Professorship and retirement days

After his travels Lönnrot returned to his position as medical officer in Kajaani. In 1849 he married Maria Piponius, who was twenty years his junior and a cousin of Johan Vilhelm Snellman.

Five children were born between 1850 and 1860, four of whom died at a young age. In 1854 the University of Helsinki appointed Lönnrot after the death of the previous incumbent M. A. Castrén as professor of Finnish language and literature. His habilitation thesis Om det Nord-Tschudiska språket dealt with the wepsi language , which he had explored during his tenth trip. Lönnrot worked at the university for nine years until his retirement in 1862 and gave lectures on Kalevala and the Finnish language.

After his retirement, Elias Lönnrot returned to his birthplace, Sammatti, where he worked on the compilation of a liturgical hymn book and a Finnish-Swedish dictionary. Together with his co-workers, he completed the dictionary over many years by 1880. Elias Lönnrot died on March 19, 1884 in Sammatti.

Services

Literary man

The national epic Kalevala and its lesser known lyrical sister work Kanteletar are still among the most important literary works in Finland. The Kalevala in particular has had an immense impact on Finnish national consciousness and culture. Lönnrot thus laid the foundation for Finnish-language literature.

The question of Lönnrot's authorship has been interpreted in different ways. Lönnrot did not see himself as the author of the works. Based on Friedrich August Wolf's theory on the Homeric question , he assumed that there had once been a coherent epic that had broken down into individual songs over the centuries. Lönnrot considered it his task to reconstruct this epic.

Although only 3% of the verses of the Kalevala are fictitious by Lönnrot, he worked on a large part of the remaining verses and took great liberties in putting together the originally incoherent runes into a unified epic. Lönnrot himself made it clear in the preface to the Kalevala that he had changed and rearranged the runes he had collected; nevertheless, in contemporary reception, the epic was viewed in romantic transfiguration as a product of the “folk spirit” that Lönnrot had only recorded. This view was refuted by the folklorist Julius Krohn in the 1880s . From today's level of knowledge, Kalevala and Kanteletar are viewed as Lönnrot's art products.

philologist

Unlike most contemporary Finnish intellectuals, Elias Lönnrot was a native Finnish speaker, which earned him a reputation for having a better command of Finnish than anyone else. He was instrumental in developing Finnish, which until the first half of the 19th century was used almost exclusively in the everyday life of the rural population, into a cultural language. Lönnrot made a valuable contribution to this project through the publication of Kalevala and Kanteletar as well as through his linguistic work, which is why he is often referred to as the "second father of the Finnish language" after the Bible translator Mikael Agricola .

Lönnrot was one of the founding members and became the first chairman of the Finnish Literature Society (Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura) in 1831 , which has had a lasting influence on the development of Finnish-speaking culture to this day. In the dispute about the standardization of the written language, he advocated a balance between West and East Finnish dialects. For many terms that had not previously existed in Finnish, new words had to be developed. Lönnrot alone invented 300–400 new words that are still part of the Finnish vocabulary today, including words like kansallisuus (“nationality”), kirjallisuus (“literature”) or tasavalta (“republic”). The Suomalais-ruotsalainen sanakirja ("Finnish-Swedish dictionary", 1867–1880) published by Lönnrot was the first comprehensive Finnish reference work of its kind with over 200,000 keywords.

journalist

Elias Lönnrot worked as an active journalist for over four decades. Following the example of Johan Vilhelm Snellman , he considered it his duty to promote Finnish national awareness and culture through public relations. The texts were intended to establish Finnish as a written language and were aimed at both the educated and the peasant population. Despite their knowledge of the written language, the rural population was not interested in reading newspapers because they were not used to reading secular texts.

Lönnrot published the first Finnish-language magazine Mehiläinen between 1836 and 1837 and from 1839 to 1840 . In addition to cultural-political contributions, Lönnrot published parts of the folk poetry he had collected. The magazine initially had a circulation of 500 copies; but reader interest quickly waned and the project turned into a financial failure. Lönnrot also wrote for over a dozen other publications, including Snellman's influential magazine Saima . After it was discontinued by the Russian censors at the end of 1846 because of its liberal-liberal line, Lönnrot Snellman helped found his new magazine Litteraturblad för allmän medborgerlig bildning ("Literature sheet for general civil education").

doctor

Elias Lönnrot was able to gain his first practical experience as a doctor during his studies in 1831 in combating a cholera epidemic in Helsinki. Between 1833 and 1854, interrupted by several long leaves of absence for his collecting trips, he practiced as a district doctor in Kajaani. The area had previously been ravaged by bad harvests and famine, and so Lönnrot's official correspondence recommended that food be sent to the bitter-poor region instead of medicine. Lönnrot campaigned for reforms in health care and, in particular, better public education on health care. He published several writings such as Suomalaisen Talonpojan Kotilääkäri ("The Finnish Farmer's Doctor", 1839), a medical guide for the common people, and founded the first Finnish abstinence association Selveys-Seura , which hardly anyone wanted to join. His botanical work Flora Fennica - Suomen Kasvisto , published in 1860 and one of the first popular scientific works in Finnish, contained information on the benefits of medicinal plants.

Honors

Lönnrot was (corresponding) member of several academies of science, u. a. of the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin (since 1850). On January 24, 1872 he was accepted as a foreign member in the Prussian order Pour le Mérite for science and the arts. In 1983 the asteroid (2243) Lönnrot was named after him.

Works (selection)

- De Väinämöine, priscorum Fennorum numine . (About Väinämöinen, the deity of the ancient Finns). Dissertation. 1827 (incomplete)

- Kantele taikka Suomen Kansan sekä Wanhoja että Nykysempiä Runoja ja Lauluja . ("Kantele or both ancient and newer runes and songs of the Finnish people"). 1829–1831 (four volumes)

- Lemminkäinen , Väinämöinen , Naimakansan virsiä . 1833

- Runokokous Väinämöisestä . (Runic collection about Väinämöinen). 1834

- Kalewala, taikka Wanhoja Karjalan Runoja Suomen kansan muinoisista ajoista . (Kalevala, or old runes of Karelia from ancient times of the Finnish people; so-called "old Kalevala"). 1835–1846 (two volumes)

- Kanteletar taikka Suomen Kansan Vanhoja Lauluja ja Virsiä . (Kanteletar, or old songs and ballads of the Finnish people). 1840–1841 (three volumes)

- Suomen Kansan Sananlaskuja . (Proverbs of the Finnish people). 1842

- Suomen Kansan Arvoituksia . (Riddle of the Finnish people). 1845

- Kalevala (second edition, so-called "new Kalevala"). 1849

- Abridged edition of the Kalevala for teaching use. 1862

- Suomen kansan muinaisia loitsurunoja . (Ancient incantation runes of the Finnish people). 1880

- Turo, kuun ja auringon pelastaja . (Turo, savior of the moon and sun). 1881

literature

- Raija Majamaa, Väinö Kuukka, Hannu Vepsä: Elias Lönnrot - Taitaja, tarkkailija, tiedemies , Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Helsinki 2002, ISBN 951-746-274-3 (Finnish)

- Väinö Kaukonen: Lönnrot ja Kanteletar , Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Helsinki 1989, ISBN 951-717-572-8 (Finnish)

- Pertti Anttonen, Matti Kuusi: Kalevala-Lipas , Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Helsinki 1999, ISBN 951-746-045-7 (Finnish)

- Pertti Lassila: History of Finnish Literature (German translation), Francke Verlag, Tübingen and Basel, 1996, ISBN 3-7720-2168-9

- Harald Falck-Ytter: Kalevala. Earth myth and future of humanity. Mellinger Verlag, Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-88069-301-3

swell

- ^ Website of the Finnish Literary Society ( Memento from November 15, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Cornelius Hasselblatt : History of Estonian Literature. De Gruyter, Berlin 2006, p. 95

- ↑ Lassila, p. 56 f.

- ^ Anttonen, Kuusi, p. 78

- ↑ cf. Lassila, p. 58

- ^ Lassila, p. 61

- ↑ The Order Pour le Mérite for Science and the Arts. The members of the order (1842–1881). Gebr.-Mann-Verlag, Berlin 1975, Volume I, p. 310.

- ↑ Minor Planet Circ. 7944

Web links

- Literature by and about Elias Lönnrot in the catalog of the German National Library

- Society for Finnish Literature: Biography of Lönnrots (Finnish)

- Juminkeko - Information Center for Kalevala and Karelian Culture: Elias Lönnrot in Kainuu (English)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lönnrot, Elias |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Finnish philologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 9, 1802 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Sammatti |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 19, 1884 |

| Place of death | Sammatti |