Icelandic literature

The Icelandic literature includes stories , the poetry and the theater Islands .

history

Old Norse literature: sagas and skaldic poetry

- Main article: Old Norse literature and Main article: Icelandic sagas

Old Icelandic literature is part of Old Norse literature . During this time it is difficult to distinguish it from the old Norwegian literature because the two languages are very similar. Since the Icelandic language has changed so little since the early Middle Ages, many Icelanders can still read the original old Icelandic texts.

The oldest and most important literary genre of this time is the saga , which first existed in oral form and was subsequently written down - often several hundred years later. Most of the texts of this period were written between 930 and 1050, but late sagas were written well into the 13th century - they are considered the pinnacle of saga literature. A distinction is made between sagas that tell family stories and those that tell biographies of kings or heroic sagas. The earliest were written in prose, while later the lyrical form prevailed. Sagas are still a generic term in Icelandic literature for stories of all kinds.

Typical of saga literature is the precision of its geographical information, which can still be used to locate the locations of the stories today. They process the Nordic legends of the gods and also offer the oldest evidence of Nordic culture.

At the beginning there are historiographies, especially the Íslendingabók ("Icelandic Book") by Ari Þorgilsson , the oldest known historical work in Iceland.

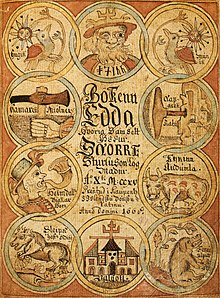

The Codex Regius , a manuscript from the 13th century, includes the "older Edda" , which was also included in the Beowulf . There is also the Younger Edda by Snorri Sturluson, also from this period.

The skald poetry was probably adopted by Icelandic authors from Norway. However, it became a domain of the Icelanders and reached its peak during the Viking Age (9th to 11th centuries).

Through the non-violent adoption of Christianity in the year 1000, the old fabrics remained alive. With the acceptance of Christianity, however, the monastic literature from Western Europe began to be received - especially by Irish monks. Numerous translations from Latin have been made. The knight poetry, however, probably came to Iceland via Norwegian translations. This is how a Nordic version of the Roland song was created during this time. By the mid-13th century, Icelandic poetry was richer than Danish, Swedish, or Norwegian literature. Fairy tale fabrics also came to Iceland from the continent. They have many foreign motifs that point to such an origin (kings, castles, forests, taverns or, for example, the motif of the royal children enchanted by a stepmother, etc.), without any adjustment to the reality of Icelandic life. Since the 14th century, these different elements have increasingly been freely combined into "lies" or "fairy tale sagas", of which 200 to 300 were passed down orally and some of them were not recorded until the 20th century.

After the start of Norwegian rule in 1264, which was replaced by Danish rule in 1380, literary development stagnated. Numerous and ongoing natural disasters such as the eruptions of Hekla in 1300 and 1341, soil erosion, plague and smallpox, which weakened traditional rural culture and decimated the population, contributed to this. Iceland became an island for fishermen.

Reformation time

The most important author of the Reformation is the last Catholic Bishop of Iceland Jón Arason , who set up the first printing house on the island.

In the course of the Reformation, all Catholic literature was discarded and replaced by Lutheran works, which were mainly taken from the Danish and German regions. Much religious literature from this period has survived.

The most important contribution to Icelandic literature was the complete translation of the Bible by Guðbrandur Þorláksson, which was printed in 1584. The Passíusálmar ("Passion Hymns") by Hallgrímur Pétursson (1666) should also be mentioned.

Romanticism and national awakening

At the beginning of the romantic period the literary magazine Fjölnir was founded. The name of the magazine, which appeared between 1835 and 1847, goes back to the Nordic legend of the same name . Fjölnir was a mouthpiece of the Icelandic language purism movement . Your co-editor Jónas Hallgrímsson was influenced by Heinrich Heine . During this time, translations of the Arabian Nights and the works of William Shakespeare were made.

Jón Thoroddsen published the first modern Icelandic novel ( Piltur og stúlka ; German: Jüngling und Mädchen , translated 1883) in 1850 , while Jónas Hallgrímsson, the founder of the Icelandic short story , published the fragment of the story Grasaferð (German: Auf der. ), Which appeared in Fjölnir in 1847 Moossuche , translated 1897) applies. "Modern" are fabrics, people and scenes that originated from contemporary life at the time and were written in the language customary at the time.

In the second half of the 19th century, the theater developed into the most important form of entertainment in Iceland, which also made a contribution to the finding of a national identity against foreign determination. The painter Sigurður Guðmundsson became Iceland's first stage designer. In particular, Matthías Jochumsson and Indriði Einarsson worked on translations of Shakespeare's plays, which lasted until the mid-20th century, but also other popular plays in which folk content was processed. At that time there were three theaters in Reykjavík, out of which the Reykjavík Theater (English: Reykjavík Theater Company, RTC ) was founded in 1897 , the first director of which was Einarsson.

20th century to the present

At the beginning of the 20th century, the drama was dominated by Jóhann Sigurjónsson , while the material continued to be taken from Icelandic folklore. The Icelandic National Theater was founded in 1950.

Halldór Laxness , a socially critical writer who converted to Catholicism in 1923 but was close to the communists and whose realism was trained in the Saga style, is the most important Icelandic writer to this day. His work was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1955 . Gunnar Gunnarsson was nominated four times for the Nobel Prize, but did not receive the award.

The novels by Steinunn Sigurðardóttir (* 1950) and Hallgrímur Helgason (* 1959) also became famous in Germany . Einar Kárason (* 1955) and Pétur Gunnarsson (* 1947) foster memories of the old proletarian, only superficially Americanized Reykjavík of the 1950s and 1960s. While Kárason is widely read in Germany, Gunnarson's works were only translated a few years ago.

Halldór Laxness , 1955

Einar Kárason , 2010

Sjón , 2004

Since the 1990s, numerous Icelandic authors have devoted themselves to the crime novel . Arnaldur Indriðason is considered a pioneer of the genre in Iceland . In 2011, over a hundred Icelandic crime novels translated into German were available.

2011 was Ofeigur Sigurdsson the European Union Prize for Literature for the historical novel Skáldsaga to Jón (dt. "Novel about Jón") over the priest Jón Steingrímsson .

Importance of literature in Iceland today

Literature is still very important in Iceland today, it has remained a leading medium “longer than anywhere else” . The Icelandic publishers publish around 1,500 new titles every year, with an average circulation of 1,000 copies per literary work.

In 2011, Icelandic literature was the guest country of the Frankfurt Book Fair under the motto “Legendary Iceland” .

In addition, on August 2, 2011 , Reykjavík was named the 29th UNESCO City of Literature.

Iceland is considered one of the countries with the highest public library turnover rate. 2005 led the country along with Norway the human development index in international comparison, in addition to the per capita income, the literacy rate of adults and the proportion of pupils and students considered within their age group. In 2014, Iceland ranked 16th out of 188 countries surveyed with a human development index of 0.899. According to the OECD PISA studies , Iceland was also in the top group among pupils who were willing to read .

Icelandic Writers' Association

The first Icelandic authors' association was founded in 1928. Next to her there was another association. Both were followed by today's Icelandic Writers' Association ( Rithöfundasamband Ísland ) in 1974, which is open to all domestic and foreign authors who have a permanent residence in Iceland. The association acts as an authors' union and represents the interests of its members vis-à-vis publishers in order to protect the freedom of literature in Iceland. It has around 350 members, a third of whom are women. There are around 70 authors in Iceland who can make a living from their profession. The state artist salary plays an important role in this. The seat of the association is in the former house of the writer Gunnar Gunnarsson , the Gunnarshús , in which there is also a guest apartment, which is used by authors all year round.

Literary prizes

Important literary prizes are the Icelandic Literature Prize and the Nordic Council Literature Prize .

Great Icelandic authors

- Snorri Sturluson (1179-1241)

- Hallgrímur Pétursson (1614–1674)

- Grímur Thomsen (1820-1896)

- Gunnar Gunnarsson (1889-1975)

- Halldór Laxness (1902–1998), Nobel Prize for Literature 1955

- Tryggvi Emilsson (1902-1993)

- Steinn Steinarr (1908-1958)

- Thor Vilhjálmsson (1925-2011)

- Guðbergur Bergsson (* 1932)

- Kristín Marja Baldursdóttir (* 1949)

- Steinunn Sigurðardóttir (* 1950)

- Einar Már Guðmundsson (* 1954)

- Einar Kárason (* 1955)

- Hallgrímur Helgason (* 1959)

- Arnaldur Indriðason (* 1961)

- Gyrðir Elíasson (* 1961)

- Sjón (* 1962)

- Jón Kalman Stefánsson (* 1963)

- Yrsa Sigurðardóttir (* 1963)

- Hermann Stefánsson (* 1968)

- Steinar Bragi (* 1975)

- Eiríkur Örn Norðdahl (* 1979)

See also

literature

- Primary literature

- Klaus Böldl, Andreas Vollmer, Julia Zernack (eds.): The Isländersagas in 4 volumes with an accompanying volume . Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-10-007629-8 .

- Secondary literature

- Josef Calasanz Poestion : Icelandic poets of modern times in characteristics and translated samples of their poetry . With an overview of the intellectual life in Iceland since the Reformation. Meyer, Leipzig 1897 ( online reprint: Severus-Verlag, Hamburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-86347-116-3 ).

- Stefán Einarsson: A history of Icelandic literature . Johns Hopkins Press for the American-Scandinavian Foundation, New York 1957.

- Wilhelm Friese : Nordic literatures in the 20th century (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 389). Kröner, Stuttgart 1971, ISBN 3-520-38901-0 .

- Einar Sigurðsson: Iceland . In: Torben Nielsen, Christian Callmer (Hrsg.): Libraries of the Nordic countries in the past and present . Reichert, Wiesbaden 1983, ISBN 3-88226-172-2 , p. 131-162 .

- Daisy Neijmann (Ed.): History of Icelandic literature , University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Neb. 2006 (History of Scandinavian literatures, Volume 5), ISBN 978-0-8032-3346-1 .

- Sveinn Einarsson: A people's theater comes of age: study of the Icelandic theater, 1860–1920 . University of Iceland Press, Reykjavík 2007, ISBN 978-9979-54-728-0 .

- Jürg Glauser: Iceland - a literary history. Stuttgart / Weimar, Metzler 2011, ISBN 978-3-476-02321-6 .

- Hallgrímur Helgason : The Saga Machine . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , Pictures and Times, October 8, 2011, No. 234

- Thomas Krömmelbein: The old Norse-Icelandic literature . In: Kindlers new literature lexicon, Vol. 20, Munich 1996, pp. 108-115.

Web links

- Icelandic Saga Database

- Author portraits on the Reykjavík City Library website

- Electronic Gateway for Icelandic Literature , University of Nottingham project (English)

- The Islandica Collection in the University and City Library of Cologne

- Presentation of the host country Iceland at the Frankfurt Book Fair 2011 with a short Icelandic literary history and author portraits as well as an overview of Icelandic literature in German libraries (archive links)

- Nadine Wojcik: Iceland's young writers. The storytellers from the Arctic Circle . In: SWR2 knowledge. October 13, 2011. Radio feature. There you can also download the broadcast and the manuscript. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- Icelandic Literature ( Memento from April 16, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) - from the online travel guide Iceland

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Icelandic literature. In: Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Benedikt Sigurdur Benedikz, Jr., Walton Glyn Jones, Virpi Zuck, August 5, 2008, accessed October 1, 2011 .

- ^ Robert Thomas Lambdin, Laura Cooner Lambdin: Saga. In: Encyclopedia of Medieval Literature. 2000, accessed October 1, 2011 (English, from Credo Reference).

- ^ A b Tilman Spreckelsen: Island Sagas. Sindbad never came to Thingvellir. In: FAZ. September 12, 2011, accessed October 1, 2011 .

- ↑ a b Islande (Littérature). In: Larousse en ligne. Retrieved October 1, 2011 (French).

- ^ Epilogue to: fairy tales from Iceland. Diederichs Märchen der Weltliteratur, Reinbek 1996, p. 273 ff. (O. Author., O. Ed.)

- ↑ See Wilhelm Friese: Reformation and Literature in Northern Europe : In: Melanchthon and Europe . Volume 1. Stuttgart 2001, pp. 27-38. u. Sigurdur Pétursson: Melanchthon in Iceland . In: Melanchthon and Europe . Volume 1. Stuttgart 2001, pp. 117-128.

- ↑ Icelandic literature . In: Munzinger Online / Brockhaus - Encyclopedia in 30 volumes . 30th edition. Brockhaus, 2011 (updated with articles from the Brockhaus editorial team).

- ↑ Translation in: JC Poestion: Icelandic poets of the modern age in characteristics and translated samples of their poetry. Leipzig, 1897, pp. 367-379

- ↑ a b Iceland. In: The Cambridge Guide to Theater. 2000, accessed on October 3, 2011 (English, from Credo Reference).

- ↑ Nobel Prize nominations ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . In: Skriduklaustur.is, accessed October 2, 2011.

- ↑ Thomas Wörtche : The Icelandic crime boom . In: Library Perspectives . No. 3 , 2011, p. 16–17 ( bvoe.at [PDF; 96 kB ]).

- ↑ a b Aldo Keel: The Iceland high. How the financially troubled saga island imagines the Frankfurt Book Fair as a cultural turning point. In: NZZ. September 28, 2011, accessed October 1, 2011 .

- ↑ Reykjavík becomes a UNESCO City of Literature , communication dated August 10, 2011. Accessed October 2, 2011.

- ↑ Reykjavik designated as UNESCO Creative City of Literature , English, communication dated August 4, 2011. Accessed October 2, 2016.

- ^ Wolfgang G. Stock, Frank Linde: Information market . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2009, p. 87.

- ↑ United Nations Development Program (UNDP): Human Development Report 2015 . Ed .: German Society for the United Nations eV Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, Berlin ( undp.org [PDF; 9.3 MB ; accessed on November 3, 2016]). Page 246.

- ↑ PISA 2009 Results: Learning Progress in Global Competition: Changes in Student Achievement Since 2000 . (Volume 5). OECD Publishing. 2011. p. 96.

- ↑ Icelandic Literature: The Icelandic Writers' Union. In: Legendary Iceland. Retrieved on October 2, 2011 (presentation at the Frankfurt Book Fair 2011).

- ↑ The Writer's Union of Iceland. In: Rithöfundasamband Ísland. Retrieved October 2, 2011 (Icelandic Writers' Union website).