Religion in the Paleolithic

Religion in the Paleolithic describes the (reconstructed) religious-cultic worldview of the Paleolithic Homo sapiens , and in some cases also of the Neanderthals .

Most scientists assume that both the cultures of the Neanderthals and the early Homo sapiens in the Paleolithic already had a religious and cultic character. The concept of religion is problematic here , as it is questionable what can be interpreted as religious and cultic at all in the Old and New Stone Age. In prehistoric research , which in the sciences mainly provides interpretations on the religion of the Stone Age, a concept of religion is hardly questioned, and so the interpretations range from the empirical-minimalist assumption that religious ideas from the Stone Age are merely manifestations of activities that are about go beyond the everyday and the material coping with everyday life, so that only a picture of the order of the universe can be accepted ( André Leroi-Gourhan ), up to Christian-influenced interpretations that see Neolithic cave art as an expression of gratitude to a deity and to the beginning of the human culture place a knowledge of God as a central moment ( Hermann Müller-Karpe ). The latter position goes far beyond the archaeological research situation.

Ethnographic comparisons of the cult and mythology of today's hunter-gatherer cultures with the history of religion are just as controversial today, as all cultural phenomena have changed over such long periods of time. On the contrary, because of their great adaptability to changed conditions, ethnic religions are all younger than the well-known high religions.

Finds that can be interpreted as religious and cultic are, for example, cave paintings , Upper Palaeolithic small art , female figurines and other sculptures such as the lion man as well as graves and their furnishings. Such finds possibly point to religious ideas in the Stone Age, for example to a life force mythology or to an examination of the life-death problem. References to lunar symbolism are accepted. The hunting magic hypothesis, however, is increasingly being criticized scientifically.

The existence of archaic-animistic religions with ideas of the afterlife, first myths and a " lord of the animals " as the first god-like idea in the early and middle Paleolithic as well as magical-spiritual religions that first appeared in the later Paleolithic or Mesolithic and through cultic rituals is considered likely and were probably already characterized by spiritual specialists .

Research and Interpretations

The first important French prehistoric was Abbe Henri Breuil (1877–1961). He represented two research approaches:

- The ethnographic comparison that looks for parallels between contemporary cultures such as the Australian aborigines and the culture of the Upper Paleolithic.

- The theory of hunting magic , which is no longer generally recognized today, e.g. B. also because the animals depicted do not consist to a large extent of the game of the time, such as the reindeer, but correspond to the living environment.

André Leroi-Gourhan (1911–1986) was critical of Breuil and rejected the ethnographic comparison and the isolation of individual images. He explored caves in their forest. Although he shaped prehistoric research in relation to artistic representations, his theory of a sexual-symbolic contradiction of representations is no longer recognized today.

One of the leading archaeologists and prehistorians today is Jean Clottes , who, together with David Lewis-Williams, put forward the theory of the “ shamanistic ” origin of paintings, which is heavily criticized, but gave new impetus to research.

Middle Paleolithic burials

The first known burials appeared in the middle Paleolithic . The dead were buried in holes in the ground, often with stone tools, props and parts of animals. These burials date from 120,000 BC. BC and 37,000 BC And are considered to be the oldest known religiously motivated acts. Since it can be concluded from them that the dead were deliberately buried, they are considered the oldest forms of cultic practices in prehistory. They appear in both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens , although the form of burials hardly differs. Burials come in different forms, the ritual design of the graves varies, but red ocher was used almost everywhere , which is often interpreted by researchers as the color of life and blood. In the Upper Palaeolithic , the red ocher continued to be used as a ritual in numerous finds.

There are features of these ritual burials that suggest that there was a belief in life after death: for example, an east-west alignment was found indicating a rising sun, a symbol of new life; embryonic postures of the dead were also found, which likewise indicate a new birth, and the ocher colorations indicate the color of the blood and of life.

It is noticeable that burials were not common at this time, but were an exception, and graves were often located in the vicinity of residential areas, so that one could conclude that the disposal of the dead was not the focus. Rather, the graves could be cult monuments expressing religious beliefs. Concepts of the afterlife , apotropaic magic, ancestral cults and numerous other interpretations are scientifically discussed. Convincing evidence for such interpretations has not yet been presented. An ancestor cult z. B. is not recognizable because there have been many child and fetal burials. The grave goods are traditionally interpreted in such a way that they represent equipment for a future life. However, this does not seem plausible insofar as these additions look arbitrary and mostly do not affect the deceased. Here one can assume that the burial had the function of giving the deceased a certain amount of attention.

It is more likely that the world view of the Stone Age was shaped by a "love of life" that referred to natural life and its maintenance and renewal. The ethnologist Hans Peter Duerr , for example, also assumes this , and finds other than the graves of the Stone Age, as will be shown below, also allow this conclusion.

Overall, the funerals seem to have arisen out of the need to face the horror of death through ritual and cultic acts. The death-life theme was continued continuously and has been the determining motif of any religious cultural production. In order to cope with this problem, apparently only the power of the cult was believed.

The ability of the Neanderthals and Homo sapiens in the Middle Paleolithic to form symbols and thus to form cultures is nevertheless viewed as controversial in archeology and religious studies. The religious scholar Ina Wunn generally denies the people of the Middle Paleolithic this ability and therefore denies that there could have been any form of religion at this time. The archaeologist C. Hackler, on the other hand, ascribes a full cultural ability to the Neanderthals, due to a materially existing and thus also intellectual and intellectual culture, which indicates a human community and linguistic communication skills. It is therefore clear that the first linguistically gifted person promptly invented a religious superstructure over his fateful existence.

Cave paintings and sculptures in the Upper Paleolithic

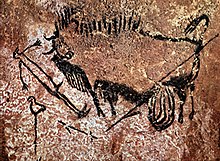

Especially in Europe it happened in the time of 35,000 BC. Until 10,000 BC Next to the tool production for art, which is considered a veritable explosion of artistic activity. The cave painting in particular is rated as the highlight of a cultural eruption of the Upper Paleolithic . Most of the cave art known to date are cave paintings from the Franco-Cantabrian region .

The cave

Nowadays it is generally assumed that the painted caves had a sacred function.

Part of the caves of the Upper Paleolithic have a tubular narrow entrance at the end of which the cave opened into a room that can be painted with animals and geometric shapes. Narrows, crevices, ovals and grottoes are often marked with red ocher. Since various shapes have been found that have a vulva shape and are marked with red ocher, it is assumed that the caves were associated with a vulva. There are also some depictions of women in the caves from the Paleolithic Age; in the Upper Paleolithic, these depictions accumulate, and at the same time there is a large number of stylized (often engraved) depictions of vulvae. Some of the Venus figurines were originally colored with red ocher. Since red ocher was also used later as a ritual, it can be assumed that this also played a role in the Upper Paleolithic. It is possible that this is a symbolism that is related to later various initiation rites in which a new birth takes place by returning to the uterus. In this context, the representation of animals in the caves could indicate that the animals that cyclically disappear and return in nature also enter the cave to be reborn there.

Animal representations

It can be assumed that those hunting societies were dependent on nature as the central aspect of life. It is therefore likely that the symbolizations of Stone Age art revolve around this subject of dependence on nature. Depictions of animals play a dominant role in the cave paintings. There are certain forms of expression: For the most part, animals are depicted that are characterized by body thickness, e.g. B. bison, cattle, mammoths, rhinos, lions and wild horses. Stone Age people did not have our present-day distance to animals, which regionally only ensured their survival. The representation of such animals can be understood as a representation of the longing for survival. Representations of people are rare in the caves. There are examples of two main forms: on the one hand as injured (spared) men and on the other hand as animal-human (so-called "magicians") or hybrid beings.

Since the focus of the cave pictures is on depictions of animals, this can be interpreted as an identification of people and animals - or their characteristics. Proof of this is the Isturitz bone stick, on which human sexuality is paralleled to that of animals. In addition, animals represented the main life resource for humans. The cave paintings could have had the purpose - contrary to the hunting magic theory - to bring the animals to regeneration through the paintings and to make amends for the sacrilege of killing. They could also have been hierograms that symbolized higher powers. This would also explain that people are portrayed as victims or hybrid beings occur. Apart from this, other symbols explained below also indicate such an assumption.

Lunar symbolism

It is noticeable that snakes, fish and birds are very rare. Besides, there are no landscapes. The physical power or speed of the animals shown could in principle indicate dynamism, vitality and omnipotence. Most of the animals are shown moving up to depictions of animals swirling around one another, as it were; there is an impression of pulsating life. Another characteristic of the animals depicted is that, apart from the horses, they all have antlers, horns or tusks. The representation of the horns mostly has peculiarities that may have been linked to a symbolic expression.

In the caves of Lascaux , Chauvet and in some of the Dordogne , the horns are shown in a semicircle, turned towards the viewer and not in perspective, although the painters otherwise dominated the perspective. In some representations, the horns also look like they were drawn in later. It can be assumed that there is a relationship to the moon, especially because in later cultures the moon horn was a cult symbol, e.g. B. the stylized cult horns in the Minoan culture and in Egypt as cow horns of Hathor or Isis .

The importance of the horns and antlers is emphasized by the fact that the paintings emphasize the horns and antlers in particular and often depict them in an exaggerated manner, in contrast to the naturalism of the animal representations.

There is, however, no connection to sexuality, despite the assumed cultic relationship to life; there are no sexual depictions of mating animals. If Stone Age art were to be about life-death-regeneration myths, then regeneration and birth-rebirth would only be associated with the feminine principle; possibly there was no knowledge of male conception in this period of mankind. In parthenogenesis can be inferred where the world z due to the myths of later cultures. B. is born from an egg or from a goddess up to the virgin birth of Jesus. The main representation of women in the female figurines also indicates the central cultic function of the feminine.

A relief that probably has a lunar symbolism in connection with the feminine is the Venus von Laussel or "Venus with the horn" with an estimated age of 25,000 years. The woman pictured is holding a bison horn with 13 notches. She is naked, faceless and with arms and legs that are too small. Originally it was painted with red ocher. The bison horn can be understood as a symbolization of the crescent moon, the thirteen notches could be related to the phases of the moon from the appearance of the new crescent moon to the full moon, but also to menstruation.

Symbolism of the breath of life

In the cave art of the Ice Age there are signs that appear on the mouth and nose of the animals. It is assumed that this could be a symbolism of the breath of life. In a (controversial) cultural comparison , such a concept can be seen in many recent hunter-gatherer societies and in many forms of shamanism , but it is also known in agricultural cultures and urban societies.

Likewise, there is an abundance of signs that combine human and animal representations. Possibly this is a deliberately created symbolism of the bond between humans and animals, the representations of the 'magicians', animal-human hybrid beings, point to the same symbolism. In connection with the breath of life, there could also be a symbolism of the general life force that connects humans and animals.

Categories of abstract signs

There are a variety of abstract signs and symbols in the caves. What is striking is their greater number than naturalistic representations. There are simple signs such as lines, points, straight lines, and there are more complex signs such as grids and ladders, sometimes house-shaped or club-shaped structures. For a long time, these signs were ignored in research, at most they were interpreted specifically, for example as houses and clubs, which is no longer recognized as an interpretation today. Leroi-Gourhan started from the psychoanalytically motivated assumption that these are sexual symbols. He tried to relate these signs to the animal species and cave sections supposedly corresponding to them and thus to reconstruct a binary principle of femininity and masculinity. These hypotheses are increasingly being called into question.

In some more recent psychological theories of shamanism it is postulated that these abstractions are neurophysiological phenomena that occur in trance states, since in shamanic trance the shamans often see light signals that often coincide with those in the caves, for example points, lines, Grid. Bosinski has pointed out that certain signs in the caves are limited to small geographical areas, which would mean that the postulated trance phenomena would have produced different signs in different areas. For this reason, Bosinski does not consider the thesis tenable, and there is also further controversy with regard to this shamanism theory.

However, Bosinski does not distinguish between categories of signs: there are two groups, signs that are simple and geometric, and signs that are complex, such as house-like and club-shaped signs. The former group of simple characters is spread across regions, while the complex characters are regional and local. The complex signs are not present in shamanic trance experiences.

So the signs probably didn't all have an origin and a meaning, but one would have to start from a differentiation of the signs in order to analyze them. A distinction can be made between signs that are simple and demonstrably have a Stone Age tradition and those that are assigned to other images and therefore have to be interpreted in this context.

The vulva is often depicted, often simplified and stylized in a symbolic way, but sometimes also depicted naturalistically. Vulvae were already depicted in the Aurignacia .

In view of images on which z. For example, if a stylized vulva is hit by a black arrow, this is probably also a life-death mythology, the black arrow also functions as a death symbol in other images. One can conclude from this that vulva had nothing to do with fertility or sexuality, but symbolize the life-giving womb. Since vulvae are common in caves, it can be assumed that it was a cult of regeneration, also in view of the symbol of the cave itself as a female womb. At the center of this cult would have been the symbol of the woman and the feminine.

Fixed signs are also grids, but they were more common in cabaret and not in caves. Lattice finds are plentiful. The first lattice signs were already found in the Blombos cave , these were diamond patterns on engraved ocher. These pieces date from around 75,000 BC. In the Neolithic , the lattice forms were also more widespread in the religious sense, although no conclusions can be drawn from them for the Paleolithic. The Fontainebleau caves, which date from the Mesolithic , are littered with bars, and this symbol may have had a central cultic significance here.

The signs occurring in the Paleolithic can be found in a similar or modified form in later cultures. From the reconstructed religious meanings of later epochs, conclusions can sometimes be drawn about the religious ideas of the Paleolithic. Whether and to what extent such conclusions are permissible remains a matter of dispute in research.

Prehistoric shamanism

Cave art has been associated with shamanism since the beginning of the 20th century . Since the end of the 20th century, reference has also been made to trance and altered states of consciousness , whereby it is assumed that there are three phases of these states of trance, which can also be recognized in the motifs of cave art. These theories are mainly related to ethnographic parallels from South Africa. The cave art is thus seen here as an illustration of trance visions.

In general, the shamanism theories have been heavily criticized, u. a. also the scientifically untenable neuropsychological and ethnographic comparisons, as these only relate to isolated data in South Africa. The postulated three trance states are mostly only found with low doses of LSD and show no connection to Ice Age art. Another argument against producing the pictures in trance is that these pictures are often carefully planned and artistically very elaborate. The animal-human hybrid beings, which are interpreted as shamans, are evidence of the shamanism theory. However, there are few such figures in cave art, so they cannot be considered representative. There is also no evidence that it cannot be a question of fantasy beings, magicians, mythical beings or people disguised as animals. It is also often assumed that the cave wall is a kind of curtain to another, spiritual world that the artist tries to reach by stepping through this curtain or seeing animals pass through it. However, these assumptions have nothing to do with shamanism and are not supported by any evidence.

The trance theory is also criticized for the fact that there are up to 70 different types of trance, this is not scientifically defined, and trance is not a mandatory indicator of a form of shamanism.

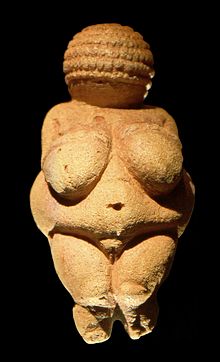

Venus figurines and depictions of women

So-called Venus figurines have been found in great abundance in vast geographical areas, the most famous of which is the Venus von Willendorf . Their interpretation is controversial. Most of the theories about the characters are unsustainable from an archaeological and scientific point of view. Nowadays it is assumed that these are not goddesses and also not exaggerated representation within fertility cults . This will u. a. ethnologically and historically justified, since in non- stratified societies there is no pantheon with a heaven of gods at the top and an increase in fertility is not in the interests of hunter-gatherer cultures. Such societies usually have some form of birth control. For this reason, interpretations of the figurines as priestesses are to be rejected.

The figurines were often interpreted as pregnant women, from which a fertility cult was derived. However, the assumption of such a cult cannot explain all representations, as firstly there are no mother-child representations and secondly, children are a burden for wandering hunters and gatherers due to their high care needs. In addition, there are not only full female figurines, on the contrary, about a third of the figurines do not have lush body shapes. In addition, in half of the approximately two hundred finds, no clear gender characteristics can be identified. A half-relief depiction of two creatures connected in the shape of an egg, found in Laussel and at least 20,000 years old, was interpreted as an expression of the binary distinction between the sexes. The relief was also interpreted as Mother Earth and Father Heaven or as a birth scene.

A comparison with Neolithic and later finds of depictions of women is at least problematic, because completely different social and economic circumstances existed from the Neolithic. In addition, most Paleolithic figures share features that indicate a common symbol and that cultural traditions relating to the figurines were spread across Europe. The Neolithic figures, on the other hand, are clearly differentiated in terms of representation, details and cultural context; they also differ from the Paleolithic figurines, so that the Neolithic sculptures can only be interpreted regionally.

On the other hand, in many ethnographic examples the use of figurines as magical objects to induce pregnancy is known, but this does not express a general fertility cult.

Many of the Paleolithic female figurines have been found in a domestic context, in the first huts and houses, near the hearth. In many traditional societies, women have the role of making fire and are related to the home and family. The context of the finds suggests that such roles could have existed as early as the Paleolithic, so that these figures show less goddesses, but ghosts, which show a symbolic connection of the protection of house and hearth.

The female statuettes, which in abstract form only show breasts and rump, can be better interpreted. B. the Venus figurines from Gönnersdorf . A series of threatening and soothing gestures and postures are known from human ethology, which are also found in artistic objects among many peoples and ethnic groups, e.g. B. phallic statuettes and handprints. Such objects are often attached to doors to ward off threatening forces. From this one can conclude that the abstracted female figures are the soothing gestures of pointing and presenting the breast, which thus expresses a religious-magical practice.

Despite these connections, there could also be a more profane explanation for the statuettes. It could also simply be toys for children, since small figurines are also used as dolls in many cultures.

Another interpretation of the figures takes Clive Gamble, who assumes that the Venus statuettes could have been a symbol of communication. This is indicated by their widespread distribution and the long period of their formation. It could be a general symbol that has linked different municipalities. The period of creation of the figurines lies in the time of maximum freezing, when it was perhaps necessary for groups to establish a larger social network with other groups. In addition, the figurines do not come from caves, but from the context of the find one can conclude that they may have served as an object of observation.

However, it remains unclear which specific function and message the characters should convey. Gambles's thesis was criticized that the spread of the figures over 10,000 km and over 10,000 years is not plausibly explained, since this could not have taken place through emigration of groups. From an archaeological-ethnological point of view, this is assumed for the reason that hunters generally do not wander aimlessly, but rather a base camp is available and a larger area is hiked in the annual cycle. Extensive hikes over 10,000 kilometers probably did not take place.

In the Gönnersdorf-type depictions of women and other related depictions, it is assumed that some dance scenes are depicted. These could be ritual dances. Since these scenes are placed near fireplaces, and these are viewed as cultic in many cultures, there could be a connection to cultic dances.

See also

literature

- Jean Clottes, David Lewis-Williams: Shamans. Trance and magic in stone age cave art. Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1997.

- Margaret Ehrenberg: Women in Prehistory. University of Oklahoma Press, 1989.

- Ariel Golan: Prehistoric Religion. Mythology, Symbolism. Jerusalem 2003.

- Timothy Insoll: The Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of Ritual and Religion. Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Joest Leopold, Angelika Vierzig, Siegfried Vierzig : Cult and Religion in the Stone Age. Celebration of life. Engraved caves in the Paris Basin. Isensee, Oldenburg 2001.

- Andrè Leroi-Gourhan: The religions of prehistory. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1981, ISBN 3-518-11073-X .

- Felix Müller: Gods gifts - rituals. Religion in the early history of Europe v. Zabern 2002

- Max Raphael : Rebirth in the Paleolithic. On the history of religion and religious symbols . Published by Shirley Chesney and Ilse Hirschfeld, Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1979.

- Brigitte Röder , Juliane Hummel, Brigitta Kunz: goddess twilight. The matriarchy from an archaeological point of view. Munich 1996.

- Homayun Sidky: On the Antiquity of Shamanism and its Role in Human Religiosity. In: Method and Theory in the Study of Religion. 22nd Brill 2010.

- Noel W. Smith: An Analysis of Ice Age Art. Its Psychology and Belief Systems. Lang, New York 1992.

- Siegfried Forty: Myths of the Stone Age. The religious worldview of early humans. BIS-Verlag of the Carl von Ossietzky University, Oldenburg 2009.

- Ina Wunn : Where the dead go. Cult and Religion in the Stone Age. Isensee, Oldenburg 2000

Web links

- Britannica: Prehistoric Religion (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 9.

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, pp. 9-11.

- ↑ Josef Franz Thiel: Religionsethnologie. Berlin 1984.

- ↑ Ina Wunn: The evolution of religions. Habilitation thesis, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Hanover, 2004. p. 97.

- ↑ S. Vierzig, 2009, p. 49 ff.

- ↑ a b p. Vierzig, 2009, p. 47.

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 48.

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 48 f.

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 34

- ↑ a b p. Vierzig, 2009, p. 37

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 38 f.

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 40

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 39

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 41

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 42

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 43

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 44

- ↑ J. Leopold et al., 2001, p. 37

- ↑ J. Leopold et al., 2001, p. 32 f.

- ↑ J. Leopold et al., 2001, p. 34 f.

- ↑ J. Leopold et al., 2001, p. 40

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 51 f.

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 50.

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 53.

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 53 f.

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 60 f.

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 66

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 68

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, pp. 85-87

- ↑ Noel W. Smith, 1992, pp. 58 ff.

- ↑ Noel W. Smith, 1992, pp. 63 ff.

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 69

- ↑ a b c S. Forty, 2009, p. 70

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 71

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, p. 72

- ↑ Homayun Sidky, 2010, pp. 68-92

- ↑ Timothy Insoll, 2011, p. 350 f.

- ↑ Timothy Insoll, 2011, p. 350

- ↑ B. Röder et al., 1996, pp. 187-228

- ↑ M. Ehrenberg, 1989, p. 74

- ↑ a b c d e M. Ehrenberg, 1989, p. 75

- ↑ a b Ina Wunn, 2000, p. 19

- ↑ B. Röder et al., 1996, p. 202

- ↑ B. Röder et al., 1996, p. 204

- ^ EJ Michael Witzel : The Origins of the World's Mythologies. Oxford University Press, New York 2012, p. 379 f.

- ↑ M. Ehrenberg, 1989, p. 72

- ↑ B. Röder et al., 1996, p. 208

- ↑ S. Forty, 2009, pp. 159–161