Hunting magic

In ethnology, hunting magic stands for magical practices in ethnic religions (in particular the animistic ideas of hunters and gatherers ) in order to bring about the success of a hunt with the help of superhuman powers . In detail, the methods differ considerably: Either the hunting weapons are magically “charged” by “discussing” them with magic formulas or by coating them with magical substances; a spiritual connection is established with the souls of the prey animals in order to make them submissive; Or consecrated animal figures or pictures are shot, so that the arrows or spears can later be just as successful with the real animals.

The term became known as hunting magic of the early days at the beginning of the 20th century through a theory put forward by Salomon Reinach , which Freud deals with in totem and taboo . In the middle of the 20th century, Reinach's theory, especially due to its further development under Henri Breuil and Henri Bégouen , was regarded as a kind of dogma in the research of the cultic rituals of early and pre-human beings .

The Ethnology had to draw a picture of early and pre-humans at this time that the free and unconcerned cavorted with the idea of "primitive" ( "noble savages") was associated in a world of plenty. The book by J.-H. Rosny the Elder The War for Fire ( La Guerre du feu ), on the other hand, showed the early humans as weak beings who fought for survival in a hostile world.

As an interpretation of religious and cultic practice of the Paleolithic , the concept of hunting magic is nowadays mostly rejected in research.

Early hunting magic

The view of the art of early and pre-human beings as “the magical art” therefore assumed an exclusively practical goal, and accordingly it contributed above all to survival. Henri Bégouen expressed this idea in the words: "The art of that time is purposeful".

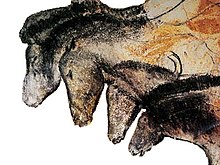

The second basis of the theory of “hunting magic” puts the cave and especially the cave painting at the center of the considerations. The fact that prehistoric people ventured so far into the darkness and danger of underground areas and made their drawings in remote places was interpreted to mean that the point was not to create drawings that wanted to be "seen". According to the theory of hunting magic, this could only serve one magical goal: the execution of the drawing or the sculpture was the actual “magical” motif. The depiction of the animal itself was a cultic act that had value in itself. Once it was carried out, its immediate and material result, the image, had no further meaning. This theory also explains why so many figures are superimposed on the same cave walls and barely visible engravings were made.

The theory of hunting magic is thus found in the explanation of the art and religion of early and pre-human beings. It is believed to be allowed to postulate that in the notion of “primitive beings” the depiction of every living being, be it as a drawing or as a sculpture, is a form of existence or an emanation of this very being. The following idea is also postulated as existing: If a person takes possession of the image, he has power over the being itself. This part of the theory was supported by a then common interpretation of the observation that many pre-civilized people felt real fear when one they photographed or made a drawing of them. This supported the assumption that early and prehistoric humans also believed that the representation of an animal indirectly enabled them to control it.

According to the theory of hunting magic, magic practices pursued three main goals: hunting, fertility and destruction. The hunting magic should lead to successful hunting expeditions. For this purpose, the prehistoric and prehistoric men took possession of the representation of the animal they wanted to kill, and thus of the animal itself. They are said to have enhanced the magical effect by adding arrow-shaped symbols to the representation of the animal, and wounds on some animals ( Niaux ), depicting animals in a ceremonial act of killing or sacrifice or depicting their fall ( Font-de-Gaume ). The drawings of incomplete animals should supposedly aim to deprive them of parts of their abilities, so that they can be approached more easily and they can be killed more easily.

While the hunting magic was dedicated to the great preferred hunters of horses, bison, aurochs, ibex, reindeer and deer, according to the theory, early and pre-humans also practiced an annihilation magic. This, according to the idea, dealt primarily with animals that are dangerous to humans: big cats and bears ( Three Brothers Cave , Montespan). Finally, the fertility magic should, according to the theory, achieve that beneficial animal species reproduce. In addition, the early and pre -humans depicted animals of different sexes, also in scenes that preceded a mating (the bison made of clay in Tuc-d'Audoubert ), or pregnant females.

literature

- Henri Breuil: Beyond the Bounds of History. Scenes from the Old Stone Age . Gawthorn, London 1949, (Reprinted by AMS Press, New York NY 1976, ISBN 0-404-15934-6 ).

- Henri Breuil , MC Burkitt: Rock paintings of Southern Andalusia. A Description of a Neolithic and Copper Age Art Group . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1929 (Reprinted by AMS Press, New York NY 1976, ISBN 0-404-15935-4 ).

- Sigmund Freud : Totem and Taboo.

- Salomon Reinach , Elizabeth Frost: The Phenomena of Animal Toteism . Kessinger, Whitefish MT 2010, ISBN 978-1-161-55076-4 (Reprinted from: Salomon Reinach, Elizabeth Frost: Cults, Myths and Religions . D. Nutt, London 1912).

- Salomon Reinach, Elizabeth Frost: Art and Magic . Kessinger, Whitefish MT 2005, ISBN 1-425-36238-9 (reprinted from: Salomon Reinach, Elizabeth Frost: Cults, Myths and Religions . D. Nutt, London 1912).

- J.-H. Rosny aîné, Louis-René Nougier: La Guerre du feu . Hachette-Jeunesse, Paris 2002, ISBN 2-01-321943-1 ( Le livre de poche jeunesse. Roman historique 1129).