Weapons (viking age)

This article deals with the armament of the Viking Age (800-1050 AD) in Northern Europe.

Source criticism

This article is essentially based on Hjalmar Falk, Old Norse Weapons . In contrast to the history of events, the source criticism plays only a subordinate role in the description of the armament in the Viking Age (800-1050 AD). Because the description of non-historical events, legends and miracle reports are usually quite useful sources for the civilizational and cultural context in which the events are placed. The investigation, for example, whether certain weapons, which are described in the Laxdæla saga, the events from the 10th century written around 1250, were already used at this time, requires a more detailed classification of the Viking Age than is done here can. It is sufficient here that both the author and the reader considered the description to be realistic and drew from a tradition that the equipment already knew. Doubts about the source value are, however, appropriate where the protagonists of a story are ascribed a particularly lavish armament. This is especially true for the ornaments, e.g. B. for an extensive sign painting. The relatively slow development of civilization in the Scandinavian Middle Ages made it possible, with great care and with the aid of archaeological finds, to apply descriptions of armament from the 13th century to the Viking Age. This differentiation is not made here.

Active armament

sword

There were both single-edged and double-edged swords. The larger single-edged swords were called langax or scramasax (the sword on the far left in the picture). The blade was usually 80 cm long. The length was prescribed for the Holmgang (duel).

There were also short single-edged and double-edged swords. In the Flateyjarbók it is described in II, 85 that men hid their swords under their clothes. They couldn't have been long swords.

According to archaeological finds, the oldest swords of the Iron Age were double-edged. The shape of the tip of the later single-edged swords suggests that they were mainly used for stabbing, which is why they were called lagvápn (to leggja, "stab"). But the reinforced back also gave the sword more force when it hit. While the handles of double-edged swords were often elaborately decorated, this was less common on single-edged swords. In addition, a “skalm” is often called, which means a short knife of the simplest kind. The skalm is not mentioned as a weapon in the sagas, but in the Edda. This suggests that the “skalmum” were already out of use by the Viking Age. They are only mentioned as knives in the hands of giantesses and sorceresses.

In the past there were also curved, that is, sickle-shaped swords, as mentioned by Saxo Grammaticus : “Speak! what do you fight with a crooked sword? "

A good sword is forged from several layers. Two types were used: Either you had hard blades on each side and softer material in the middle, or you had a hard blade throughout and a layer of softer iron on the top and bottom. The double-edged swords were first developed in the Franconian Empire. Imported swords were wanted, especially from the Rhine Valley. Foreign trademarks are engraved on a number of Scandinavian swords, for example ULFBERTH or INGELRI. There are so many swords with these two words that they could have been sword types. Charlemagne banned the export of swords to the Vikings under penalty of death, but to no avail. The quality of the native swords was not particularly good at first. The iron was too soft. In the sagas it is reported that the swords were bent during battle and kicked straight. The story of the Battle of Svolder says:

“[King Olav] saw that the swords cut badly. Then he shouted out loud: 'What are you giving so blunt blows: I can see that none of them cuts any more.' One man replied, 'Our swords are blunt and badly smashed'. Then the king went down into the anteroom of the ship, unlocked the ark of the high seat, took out many sharp swords and gave them to his men. "

Snorri's contemporaries must have been familiar with the poor quality of swords and that a “French” sword, as the king took from his chest, was so valuable that he could not afford to equip his entire team with it . The import to Norway mainly related to the blades. The handles with pommel were attached by local blacksmiths made of resinous pine wood with elaborate local decoration, which also enables dating. Very good swords also got names. So the sword of Þórálfur hinn sterki Skólmsson (Þoralfur the strong) was called “Fetbreiður” (broad foot), and the sword of King Olav the Good was called “Kvernbit” (millstone biter). There is no mention of swords forged in the north in the sagas. The term swordsmith does not appear in the job titles either, only that of sword grinder (swerdhsliparar). In the myths, swords were mainly forged by dwarves. It is also often reported that good swords were acquired abroad: Egill Skallagrímsson acquired his sword 'Naðr' in Courland, Harald Hardråde had brought his excellent sword with him from Sicily. The 'Welschen' swords came either from England, Scotland or Franconia.

The pommel at the top was also sometimes hollow, and wound medicine or relics were inserted into it.

In the early days, swords were sharpened with a file, later the whetstone was used. Good swords could be polished to a shine when they were sharpened. This indicates that from the word brúnn "shiny" the verb brýna "wetzen" is derived. The use of the grindstone (slípisteinn) was apparently taken over from England, as the expression "mēcum mylenscearpum" (sharp-edged swords) in the song about the battle of Brunanburh from the Anglo-Saxon-Chronicle, line 24 shows.

The sword scabbard consisted of two logs of wood covered with leather. It was shod with metal at the lower tip ( chape ) and originally also at the top of the hanger ( scabbard mouthplate ). In the Viking Age, the metal fittings were only on the lower tip.

The sword was carried on a weir hanger , shoulder strap or belt. They have come down to us in the Vimose bog find . The sword was carried on the left side. But also the right side, as was common with the Romans, obviously appeared. Some also wore a sax as a second sword in addition to a long sword. In the Königsspiegel even recommends a dagger knife in addition to two swords, one of which is slung around the neck and the second hangs on the saddle. The larger, sword-like long axes were mostly found in connection with Viking settlements in England and Ireland.

According to the sources, the sword was sometimes wielded with both hands in order to increase the striking power ("tvihenda sverðit"). In the process, the shield was thrown away, indicating that it had already been cut up. But the term "höggva báðum höndum", which has the same meaning, is also used when the fighter quickly changes the sword from one hand to the other. The practice of both hands in the use of weapons is mentioned in the Königsspiegel as an old custom.

The sword served not only as a weapon, but was also used in symbolic acts, such as the introduction of a public official. In Norway it was first used as a royal sword for a coronation ceremony when King Håkon Håkonsson was installed . On the journey with the bride-to-be, the suitor placed a bare sword between himself and the bride. The members of the royal retinue (Hirð) swore their oath of office while embracing the ruler's sword pommel.

knife

The Königsspiegel recommends a good dagger (brynkníf góðan) as well as two swords for the cavalry warrior. The name Brynkníf suggests that it was meant to pierce the enemy's armored joints. This knife was usually single-edged and the handle made of whale bone.

The more common knife was a fairly simple, one-sided knife of normal design, called knifr . This was found in most of the graves because these were the only weapons approved for everyone, even slaves. Gun knives sometimes had decorative inlays on the blade of the knife. The tang goes through the more or less cylindrical handle. The knife played an important role in Scandinavia. A large number of knives were found at burial sites for both men and women and children.

The other type was the sax , which was mostly a bit heavier than the ordinary knife. The knife-like short axes could be made by ordinary blacksmiths. Compared to the sword, this crude weapon was relatively easy to make and use.

Axe

From a purely technical point of view, the ax was an easy-to-make device and also more versatile. While ax finds are rather rare in Norwegian grave finds in the older Iron Age, they appear in the graves of the Viking Age as often as swords and spears. The Frostathingslov specifies that an ax was only to be regarded as proper if it was in business . The ax apparently experienced a renaissance in the Viking Age. There are different types.

The battle ax was less suitable for work. The sheet was often quite thin, but richly decorated with engravings and inlaid silver decoration. However, it is questionable whether these axes were used in combat. Usually a cutting edge made of particularly hard steel was welded on.

But vice versa, the work ax was not considered a battle ax. In the introduction to Frostathingslov it is said that injustice is being done to the king by "men declaring wooden axes to be valid weapons ..."

Executions of the battle ax

The hand ax ( handöx ) was a light and handy weapon with a long, thin handle. The ax could be grasped directly on the handle on the blade, so that the handle could serve as a support stick. The blade was wider than that of the wooden ax. The part at the other end of the socket eye could be used as a hammer.

The broadax ( breiðöx ) outside the Nordic region as a Danish ax 'known had a very broad leaf that the shank tapered eye. It was the common battle ax in Scandinavia. The steel cutting edge was inserted into a groove in the blade and welded. In Norway the fighter could choose between broad ax and sword. This battle ax was often wielded with both hands.

The bearded ax ( skeggöx ) was elongated downwards rectangular. It had a long shaft, and the rectangular extension was used to pull the enemy ship towards it like a hook.

There was also a double-edged ax, the bryntroll . This double ax was often provided with a sharp iron point.

The Anglo-Saxons also used throwing axes in the Battle of Hastings. Axes, like other Scandinavian weapons, were often given names. After the Snorra Edda by Snorri Sturluson, axes were often named after troll women.

How the leaf was attached to the stem cannot be determined with certainty. The stem could have been thickened at one end and pulled through the shaft eye, the thickening not fitting through the eye. At the lower end, a nail prevented it from slipping on the shaft. Such methods of attachment were found in Nydam. Occasionally it is also reported that the blade of the ax slipped out of the handle.

Club

In Danish bog finds, clubs (kefli) in various shapes have been recovered. They were made of thick wood, usually oak, and thinner towards the handle. There were clubs with heavy heads and short stems, but also long, pole-like clubs. Some were shod with iron and ended with a head with iron nails. According to tradition, clubs were mainly used by slaves and small farmers. That a free fighter used a club instead of his sword is only attested to in opponents who were immune to sword, spear or arrow by magic. Saxo Grammaticus also describes in the 8th book of his Gesta danorum the regular use of iron- shod clubs in battle.

spear

Another weapon, especially in ship combat , was the spear ( spjót ). There were three types: the hand spears (“lagvápn”) were stabbed, the javelins (“skotvápn”) were thrown and the “höggspjot”, similar to a halberd , was hewn. Spears were also inlaid with gold.

The simplest type of thrust weapon was a wooden rod, the tip of which was hardened in the fire. It was called "sviða" ( svíða "sengen"). This type of skewer is already mentioned in Tacitus.

There was also a light javelin ( gaflak ) that is rarely mentioned. This is a Celtic loan word. It must have been very small javelins, i.e. hand arrows. Olaf Tryggvason is reported to have thrown two spears at the same time, i.e. with both hands, at the Battle of Svoldr.

The javelin with a wedge-shaped tip was the "Geirr". This is also the name of Odin's spear. There was also a light throwing spear called "Fleinn". It had a long, thin, flat metal tip. There was also the "Broddr" or "Broddspjót", a light throwing spear similar to the "Fleinn", but the tip of which was almost square. both were rarely used in the Viking Age because they are rarely mentioned.

He was thrown from ship to ship and one was evidently very accurate.

Throwing spears were often provided with throwing loops or flybelts, which gave them greater range or penetration.

Fjaðrspjót (feather spear ) is also known as a thrust weapon . It was a heavy spear with a broad leaf spring at the tip. The heavy spears usually had a cross bar at the top of the metal point. This was supposed to prevent the pierced opponent from running against the spear and thus coming within range of the attacker with his cutting weapon.

The other type of spear was the Höggspjót, which could be used as a stabbing and cutting weapon. The shaft was usually short. The point consisted of a double-edged sword-like blade that tapers at the front. The weapon is mentioned in the Ólafs saga helga .

The most common type of Höggspjót was the "Kesja". There were light versions that could be hurled with both hands and heavy versions that could even be wielded with both hands. There were also long-stemmed ones. Before the battle of Stamford Bridge, Harald Hardråde asked his men in the front line to hold the "Kesja" in front of them so that the enemy could not come close to the line of battle. It was also later used for bear hunting.

Another type was the brynþsvari (well borer ). There is a description of Thorolf before describing a battle:

“Kesju hafði hann í hendi; fjöðrin var tveggja álna löng og sleginn fram broddur ferstrendur, en upp var fjöðrin breið, falurinn bæði langur og digur, skaftið var eigi hærra en taka mátti hendi til fals og furðulega digurt; járnteinn var í falnum og skaftið allt járnvafið; þau spjót voru kölluð brynþvarar. "

“He had a kesja in his hand. Its blade was two cubits long and a square point was forged on it at the front. But at the top the sheet was wide, the clamp long and thick. The shaft was no longer than one could reach up to the ferrule by hand, and it was extraordinarily thick. An iron nail held the ferrule and the entire shaft was studded with iron. Such spears were called 'fountain whorls'. "

According to Falk, the spearhead shown on the left side of the picture should belong to a 'Brynþvari'.

There were also hook spears ( krókaspjót ), which are particularly secured from the earlier Iron Age. They were also used for whale and walrus fishing. Such a spear is mentioned in chapter two of the Fóstbræðra saga.

Another polearm called atgeir is mentioned in several Icelandic sagas. Atgeir is usually translated as "Dagger wand", it is a glaive similar. Many weapons (including the kesja and the höggspjót ) that appear in the sagas were referred to as daggers or hips . No such weapons were found in graves however. These weapons were very rare or were not part of the Viking funeral customs.

bow and arrow

Little is known about bows and arrows because they cannot be found in the graves. The arches recovered from the Danish bog finds were about 1.50 m in length. The bow is even used once as a measure of length: the route for a kind of gauntlet for a thief is said to be nine arcs for an adult man. According to the finds in Haithabu, they were long bows made of yew wood. The skald Guthorm Sindri uses Kenning "elm tendon releases' King Eric Bloodaxe, from which it can be seen that arches were also made of elm wood. Sometimes the ends were stiffened with metal or bone. The middle part was often reinforced by an underlay made from another layer of wood or horn. The horn bows were probably only known as foreign weapons and are sometimes referred to as 'Turkish bows'. The arrows were barbed.

The longbows were not hunting weapons.

In addition, the crossbow ("Lásbbogi" as opposed to the "Handbogi") was in use. Bow and arrow as well as crossbow are recommended in the Königsspiegel as armament in ship combat.

The bowstring apparently originally consisted of animal intestines or animal tendons, but in historical times it was usually made of flax.

The arrows (lat. Sagitta vel lancea brevis "arrow or short lance") are often indistinguishable from short javelins ( spiculum ) in the early literature . The krokör was a barbed arrow. Then there were arrows that had a hole in the tip, which made it difficult to pull the arrow out because the flesh of the wound was pressed into the opening. This type of arrow was probably also equipped with burning tinder and used as arrows. "Bíldör" was an arrow with a sharp blade tip. With such an arrow, Finnr shot Einar's bow in the middle of the naval battle of Svold . The Þiðreks saga describes how the marksman Egill has to shoot an apple from the head of his three-year-old son at the king's command:

"Egill tekr þrjár örvar ok strýkr blaðit á ok leggr á strictly ok skýtr í mitt eplit. Hafði örin brott með sér hálft eplit, ok kom allt í senn á jörð. "

“Egil took three arrows, sharpened the leaf on one, placed it on the bowstring and shot the apple right through. The arrow tore one half of the apple away with it, and both fell to the ground at the same time. "

This is only possible with a 'Bíldör'.

The broddr was an arrow with a very sharp, polished metal tip, either three-edged or four-edged, rhombic cross-section.

The arrows were feathered at the end. The springs were glued on with resin. Hunting arrows also had a proprietary tag so that it was possible to determine who had killed which animal.

The arrow also had a ritual meaning. When he was called up, he was sent from court to court on a war campaign.

fling

Slingshots are not mentioned in contemporary Nordic literature on Scandinavian events. Only Saxo Grammaticus describes the use of hand slings and throwing machines in the 8th book of his Gesta Danorumm . The Königsspiegel recommends having throwing stones and throwing stones available for ship combat. The loading of the ships with throwing stones and their use is described in the Sverris saga in connection with the battle of Fimreite .

It is not certain whether larger stationary throwing machines were used. They are mentioned sporadically in the Formanna sögur, but then with the reference that a foreigner was there who knew how to build. They are attested for the 12th century. News of such machines from before 1100 is believed to be implausible.

Passive armament

helmet

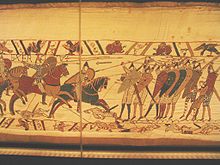

Neither fountains nor helmets can be found in the grave goods of the population . From this some conclude that they were not used and that the conical headgear depicted in the pictures were not helmets. The grave goods did not depend on the use, but on the property of the deceased, but they did not represent the entire property of the deceased. Therefore, the depicted conical headgear should not necessarily have been found. You can see them on the wood carvings of the stave church of Hyllestad (Sweden) in the National Museum in Stockholm and on the Bayeux Tapestry . A boy's grave from the first half of the 6th century has been found under the floor of the Merovingian chapel, which was built there earlier, under Cologne Cathedral, in which there was a spangenhelm made of 12 narrow bronze clasps, the segments of which were made of carved horn plates, as were the cheek flaps. So if they were made of horn plates, they shouldn't have been preserved as a rule. A grave find in Derbyshire includes a helmet with two iron ribs that cross at the top and are attached to a circular headband. The spaces between were originally filled with horn plates. On the top of the head was an iron plate with an iron figure of a boar with bronze eyes.

Such helmets made of horn could also be the cause of the modern depiction of bull horns on Viking helmets as a result of a later misunderstanding. Another possibility are depictions of warriors with horned helmets on bronze press plates, which apparently depict initiation rites in connection with berserkers. In any case, the various popular depictions of Vikings and Normans with horned helmets are wrong. They are widely used by the Scandinavian tourism industry and the media. Horned helmets were not worn by Viking Age, Germanic or Celtic warriors in battle.

→ Main article: Horned helmet

It is also possible that a simple head protection was not counted among the grave goods at all because it did not say anything about the prestige of the wearer like clothes, weapons and shields. There were also quality differences in the helmets; because it is particularly emphasized that the men of Olav the saint wore "French" helmets in the battle of Nesjar. This is supported by the fact that ax (sword), spear, shield and bow and arrow were standard equipment, but all these weapons were rarely found together in the graves. 177 gun graves from the Merovingian and Viking ages are registered in Nordfjord. Only one weapon was found in 92 of them. 42 of them were an ax, 28 were a sword, and 22 were a spear. The rest had combinations. In the Egils saga , which takes place at the end of the 9th century, it says: “When Kveldulf came back to the aft deck, he lifted the battle ax and struck Halvard through his helmet and head so that it penetrated up to the shaft.” In the Gunnlaugr Ormstungas saga At the end of a duel it is reported that one of the fighters fetches water in his helmet during a break in the fight.

The old helmets were hemispherical in shape. There were also helmets with a pointed cone shape, as shown on the Bayeux Tapestry. They had a forged iron band that covered their noses. It is not only recognizable in the pictures, it is also mentioned in writing: "King Olav struck Þorgeir of Kvistað ... across the face, and he smashed the nose cap ( nefbjörg á hjálminum ) of the helmet ...". Sometimes there were also cheek pieces and neck protection. The complete covering of the whole head with eye and breathing holes did not appear until the 13th century. Under such helmets a hood was worn, which was connected to the armor and made of the same material. Underneath was a soft, padded hat. Ordinary metal hoods also appeared, as can be seen in the illustration of the death of Olav the Saint from 1130. They were lined inside with leather. Metal hoods with a wide rim came into use only under King Sverre . Therefore the depiction of the initial of the Flateyjarbók is anachronistic. But it shows the usual steel hood in the composition time. The same anachronism can be found in the Laxdæla saga, where Húnbogi inn sterki (Hunbogi the Strong) is described (11th century): "... and had a bonnet on his head and the brim was a hand's breadth."

Helmets like the one from Sutton Hoo were worn by leaders in combat. Eyvind the skald spoiler writes about a battle between Håkon the Good and the Erich sons:

|

œgir Eydana, |

There stood the Danish people's |

It goes on to say that the king's helmet was actually gilded. This is evident from the fact that he flashed far in the sun and thus attracted the enemies, so that a warrior put a hat on his helmet.

Initial from the Flateyjarbók (1390)

Brünne

Another protection was ring fountains . Small rings of iron wire were nested, four in each. They were of different lengths. Most of them still covered the abdomen, some went up to the middle of the thigh. Initially, however, they were not widespread. Because in the Battle of Nesjar it is emphasized that the men of Olav, unlike the men of his opponent Jarl Sveinn, were hardly wounded because of these wells. Like all weapons, well-crafted fountains could have names. This is what Harald Sigurdsson says:

“Emma hét brynja hans. Hún var síð svo að hín tók á mitt bein honum og svo sterk aðaldrei hafði vopm á fast. "

“His fountain was called Emma. It was large so that it reached up to the middle of his legs and so strong that no bullet stuck to it. "

Foreign wells could be worked in several layers ( Middle Latin bilix, trilix lorica ). A double ringbrynne is reported to have been found in southern Iceland. A piece of clothing was often worn over the fountain to protect it from the weather. Sometimes they even had cloaks or other splendid robes, some of which were made of silk for the king.

jerkin

At the beginning of the 13th century, a cotton doublet - called 'panzari', Latin 'wambasium' - was common instead of the brünne. It was made of linen and tow. The leather variant did not come to Scandinavia. In the knight's sagas it is reported that a well was worn over the doublet. This use does not occur in the literary material of the north. This doublet became the common soldier's sole body protection. The Königsspiegel mentions in Chap. 37 the doublet "made of soft, blackened canvas" as the main weapon of protection on the ships. The doublet is mentioned in the gun regulations as an equivalent alternative to the Brünne, but has never completely supplanted it.

Leg protection

The fighter also wore chain pants to protect his legs. They only covered the front of the leg. At the back they were held together by straps. Linen trousers were often worn over them. There seems to have been no greaves, but metal knee protection.

sign

The shield of the Viking Age was circular. The Landslov of King Magnus lagabætir calls the simplest shield a shield made of linden wood (linda skjold). Falk considers the six 'peasant shields' in a Norwegian estate register from 1350 to be such shields. In order for a sign to be recognized by the arms chapel, it had to be held together with at least three metal straps. The illustration on the right-hand side partially shows such a shield. As a rule, they were unpainted and were therefore called "white shields". They were not considered particularly belligerent. For example, the bishop should carry 30 men and twelve white shields on his visitations. Putting on a white sign was considered a peace sign. The war shields were generally red. The contrast between white peace shields and red war shields is expressed in the saga of Erich the Red when he meets the Skrälingers. A red shield also served as a court sign, at least on ships.

The red shield was part of the compulsory armament of a warrior who possessed more than six marks of silver weighed. This shield also had to have a second layer of boards (tvibyrðr skjöldr). A special version had a rim studded with iron.

On the one hand it is said that the shields of the Danes were red,

|

hilmir lauk við hernað olman |

The ruler sealed off |

Elsewhere it is said that the Danish Vikings were called “dubh” (the blacks), the Norwegian Vikings “finn” (the whites) because of the color of their shields. Maybe the black shields were just tarred.

|

Hremsur lét á hvítar |

|

Fast arrows |

On the other hand, it is also reported that the shields were of different colors, as shown on the Bayeux Tapestry. But there are also supposed to have been shields with depicted scenes that apparently depicted the deeds of the King of the Army . This is how the skald Ottar the Black writes about Olav Haraldsson's Viking journey to Poitou:

|

Náðuð ungr að eyða, |

You could, young king, |

The poet Þorbjörn Hornklofi says in his poem about the battle of Hafrsfjord about the crew of the enemy ships:

|

Hlaðnir váru þeir Hölda |

Completely full of

big farmers |

It is also recorded that there were shields with a gold inlaid cross. This is said not only for the warriors on the ship “Mannshaupt” in the battle of Nesja, but also of King Olav's shield in the battle of Stiklestad. Shields were entirely or partially gold-plated, and precious stones were even inlaid. However, here as with the descriptions of extensive carvings, the source value is doubtful. Many descriptions of images on the shields are also incredible, for example if, according to the Laxdæla saga, Ólafur pái (around 955) was said to have had a shield with a gold-plated lion. In its time, the appearance of a lion in Scandinavia might not have been so well known that the image could have made an impression on the opposing fighters. The particularly decorated splendid shields were probably not intended for combat, but were used for decoration on festive occasions.

The sea warrior's shield could be attached to the outside of the railing.

Another type of shield was the buckler . He is mentioned in the Königsspiegel as the armament of the foot fighter during the weapon exercise. It was a very simple sign, which is evident from the price differences. The shield maker received three Øre for a red battle shield, and only half an Øre for a buckler without the hump. The Hirðskrá prescribes a buckler as well as a good shield for arming a follower.

Another type was the curved long shield, initially oval, later more and more pointed at the bottom. Later a flat variant appeared. These shields were also common in Iceland, as the Grettis saga shows in a very dramatic scene. This shape of the shield allowed the legs to be covered. The tip of the rather heavy shield could also be stuck into the ground. That they were widespread is shown by the many places in which the dead and wounded were carried away on the shields, which would not have been possible with the smaller round shields. The long shields depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry show its widespread use.

Canopy

The canopy, a wickerwork supported on four supports, provided protection for the fighters as they advanced against defensive walls. It is often mentioned that Olaf the Saint used it to cover his ships in his attack on Southwark. The Königsspiegel also mentions them in chap. 39 as protection.

Descriptions of combat equipment

In Gulathingslov it says:

“Whenever an arms whining is to be held, the administrator or landlord should announce it in autumn and hold the thing in spring. All men should go to the thing who are free and of full age, or they are offenders with three Øre, each of them. Now the men are to show their weapons, as stipulated in the law. The man is said to have a broad ax and a spear and a shield, over which three iron bands are laid across and the handle is nailed with iron nails with minimal effort. There is a penalty of three Øre on each people's weapon. Now the bonds should put two dozen arrows and a bow on each rowing place. You should pay one Øre for each arrowhead that is missing and three Øre for the bow. "

In Frostathingslov it says:

“There should be a bow at every rowing bench; The two bank mates who are going out should get it and the string for it, or atone for an Øre, and they should get the bow anyway. And two dozen arrows, shafted arrows, or arrows with iron tips, they are supposed to get the bonds, half an Øre penalty for each missing arrow and six Øre for the two dozen arrows. Every young man should have a shield and a spear and a sword or an ax. And the axes are considered proper when they are wielded, and the spears that are wielded. And if he lacks a piece of this armament, there is a penalty of three Øre on it, and if he is missing everything, there is a penalty of nine Øre, and he is not entitled to a penalty until he has procured the weapons. ... Every wooden sign should be in accordance with regulations, over which three cross bands of iron are placed and which has a handle on the inside. "

In chap. 21 of the Laxdæla saga describes how Ólafr pái got onto Ireland's coast and is attacked by the coastal inhabitants:

“Olafur ordered the weapons to be taken out and the shelves to be manned from Steven to Steven. They were also so close that everything was covered with shields, and the tip of the spear stuck out beside each tip of the shield. Olaf stepped forward to the stern. He was so prepared that he wore a fountain and had a gilded helmet on his head. He was wearing a sword, the hilt of which was adorned with gold jewelry. In his hand he carried a hook spear (Krókaspjót), which was also good for cutting, with beautiful decorations on the leaf. He carried a red shield on which a gold lion was painted. "

In the Fostbræðrasaga it says:

“Þorgeir had a broad battle ax: very large, a real gem. It was razor sharp ... He had a large fjaðrspjót . It had a hard point and sharp edges. The tube of the shaft was long and thick itself. At that time swords were seldom part of the armor. "

In the king's mirror it says:

"The man himself should have the following equipment: good and supple stockings made of soft and well-blackened canvas that extend to the belt of the pants, and on the outside, good fountain stockings that are long enough to be girded with both legs, and over them he should have good tank pants Made of canvas of the type I have said earlier, and on top of them have good knee pads made of thick iron and with steel-hard tips. On the upper part of the body he should first have a soft armor that does not go further than the middle of the thigh, and above it a good breast of good iron, which extends from the nipples to the trouser belt, and above it a good well and above that Brünne a good tank, made in the same way as was said before, but without sleeves. He is said to have two swords, one that he has girded on, the second that hangs on the saddle arch, and a good dagger knife. On his head he should have a good helmet made of good steel, which is provided with a complete face protection, on the neck a good and thick shield with a comfortable shield strap and then a good and sharp thrust lance made of good steel and well done. "

Price ratio of weapons and armor to other trade goods (around 880)

- The coveted chain mail cost 820 grams of silver, which was the equivalent of a female slave and two slaves or 28 pigs.

- A long sword with a scabbard cost 478 grams of silver, which you could buy a horse for in Northern and Western Europe.

- A knife had the equivalent of 3 grams of silver, for which 30 chickens could have been bought.

- A short sword or stirrup weighed 126 grams of silver, a price that was also achieved for 42 kilograms of grain.

- You got a helmet for 410 grams of silver; three oxen had the same value.

- A shield and a lance could be purchased for 137 grams of silver, the equivalent of a cow.

Arms made abroad were acquired through trade or looting.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 20 with reference to the Kormaks saga chap. 14th

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 9 footnote 1.

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 13.

- ↑ Guðrunakviða II, 19. There and also in the Völsunga saga it is said of the Lombards that they wore “skalmum” (plural of “skalm”).

- ↑ Laxdæla saga chap. 48; Grettis saga chap. 65.

- ^ Gesta Danorum 1st book chap. 8 : “Quid gladius pugnas incurvo?” German version .

- ↑ " 25. Ut, quoniam, in praefatis capitulis continetur in libro tertio, capitulo LXXV, 'ut nullus sine permisso regia bruniam vel arma extraneo dare aut vendere prae-sumat', et in eodem libro, eapitulo VI. designata sumt loca regni, usque ad quae negotiatores' brunias et arma ad venundandum portare et vendere debeant; quod si inventi fuerint ultra portantes aut venundantes, ut omnis substantia eorum auferatur ab eis, dimidia quidem pars partibus palatii, alia vero medietas inter missos regios et inventorem dividatur '; quia peccatis nostris exigentibus in nostra vicinia Nortmanni deveniunt et eis a nostris bruniae et arma atque caballi aut pro redemptione dantur aut pro pretii cupiditate venundantur; cum pro redemptione unius hominis ista donantur vel pro pauco pretio venundantur, per hoc auxilium illis contra nos praestitnm et regni nostri maximum fit detrimentum et multae Dei ecelesiae destruuntur et quamplurimi christiani depraedantur et facultates eccurni considium naurosticae at the consortium fidelium: constituimus, ut, quicumque post proximas Iulii Kalendas huius duodecimae indictionis Nortmannis quocumque ingenio vel pro redemptione vel pro aliquo pretio bruniam vel quaecumque arma aut caballum donaverit, sicut proditor patriae et expositor christianitatis ad perditionem gentilit rete. Quae omnia omnibus citissime a missis nostris et comitibus nota fiant, ne de ignorantia se excusare valeant. “ Edictum Pistense . In: MGH Legum sectio II. Capitularia regum Francorum Tomus II. Hanover 1897.

- ↑ Laxdæla saga chap. 49: In the last fight Kjartan has to straighten his sword again and again with his foot. Eyrbyggja saga chap. 44: In the fight at the Alptafjord, Steinþor fights with a beautiful, richly decorated sword, which is no good, but has to be straightened with the foot over and over again.

- ↑ Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga Tryggvasonar . Cape. 109.

- ↑ Capelle p. 40.

- ↑ Heimskringla. Hákonar saga goða. Chap 30, 31.

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 38 ff. With further references.

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 27 with further references.

- ↑ Song about the Battle of Brunanburh. Retrieved July 30, 2013 .

- ^ Ordinance of King Erik Magnusson on trade and prices in Bergen of September 16, 1282 in Norges gamle Love indtil 1387 . Christiania 1849. Vol. 3 p. 15. He stipulated an ore for a sword with a leather-wrapped scabbard . King Olav Håkonsson's ordinance on prices for artisans in trading towns and workers in the countryside of June 23, 1384, Norges gamle Love vol. 3 p. 220, sets ½ Marks of silver money for swordsmiths .

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 34.

- ↑ Königsspiegel chap. 38.

- ↑ Kim Hjardar and Vegard Vike: Vikinger i krig (Vikings at War) ( Norwegian ). Spartacus, Oslo 2011, ISBN 9788243004757 .

- ↑ a b Königsspiegel chap. 37.

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 42.

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 124 f.

- ↑ food Veit: Norsk knivbok ( Norwegian ). Universitetsforlaget AS, Oslo 1985, ISBN 82-00-07503-6 , p. 144.

- ^ Valerie Dawn Hampton: Viking Age Arms and Armor Origninating in the Frankish Kingdom . In: The Hilltop Review . 4, No. 2, 2011, pp. 36-44.

- ↑ Frostathingslov introductory section 21.

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 113.

- ^ Snorri Sturluson: The Prose Edda .

- ↑ "Þá gekk öxin af skaftinu." (The ax came off the shaft.) Harðar saga og Hólmverja Kap. 36. Also in Fóstbræðra saga : "… því hann hjó tveim höndum með öxi sinni hinn fyrra bardagann en með sverðinu alla Dagshríð því að þá gekk öxin af skaftinu."

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 120 with numerous quotations from the Icelandic saga literature.

- ↑ a b Saxo Grammaticus: Gesta Danorum 8th book, chapter 4 : "At ubi pila manu aut tormentis excussa, comminus gladiis ferratisque clavis decernitur." (But when the bullets were fired by hand or with the throwing machines, there was in hand-to-hand combat Swords and iron-shod clubs fought.) German translation .

- ↑ “In his hand he carried a large spear inlaid with gold. Its shaft was as thick as a fist. ” Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga helga. Cape. 215.

- ^ Tacitus Annals II, 14.

- ↑ For example in Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga helga. Cape. 249.

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 72.

- ↑ Johan Fritzner: Ordbok over Det gamle norske Sprog. Vol. I. Kristiania 1883, ND. Oslo 1954. p. 536.

- ↑ Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga Tryggvasonar . Cape. 109: "Ólafr konungr Tryggvason stóð í lypting á Orminum ok skaut optast um daginn, stundum bogaskoti en stundum gaflökum, ok jafnan tveim senn." (King Olaf Tryggvason stood on the back deck of the 'Ormin' and shot very often that day, sometimes with the bow, sometimes with the Gaflak, always with two at the same time).

- ↑ Falk (1914) pp. 66-69.

- ↑ "Now the two ships passed close by, and Karli said: 'There Selsbani is sitting at the wheel in a blue doublet.' Ásmundr said, 'I'll get him a red doublet.' With that, Ásmundr shot a spear at Ásbjörn Selsbani, and he hit him in the middle of his body, and the spear pierced him so that he got stuck in the back seat by the rudder, and Ásbjörn fell dead from the helm. ” Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga helga. Cape. 123.

- ↑ In chapter 17 of the Fóstbræðra saga the death of Þorgeir Hávarsson is described as follows: “It was Þórir who pierced Þorgeir with his spear. But this went up to him and killed him. "

- ↑ "Arnljótur hafði höggspjót mikið og var gullrekinn falurinn en skaftið svo hat að Tok hendi til falsins en hann var sverði gyrður." (Arnljot had an enormous glaive , and the booklet was absolutely driven. But the shaft was so long that the could reach handle only up to the hilt, and he was girded with a sword). and: "Þá sTod Arnljótur upp og Greip höggspjót (. sitt og setti milli Herda henni svo að út hljóp oddurinn to brjóstið" Since Arnljot stood up, grabbed his Slide and thrust it through her shoulder so that the point protruded from her chest). If this episode is related to an argument with a troll woman, the fact that a Northman possessed such a weapon in the time of Olav the Saint does not seem unbelievable to the contemporary reader. Incidentally, in Chap. 142 reports that Karl mærski (Karl von Möre) appeared before the king with such a weapon. Most of the time the word is translated as halberd, which is wrong, as halberds were only invented in the 14th century.

- ↑ Formanna sögur VI, 413: "hafið svá allt 'kesjurnar' fyrir, at ekki megi á ganga".

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 79.

- ↑ a b translation by Felix Niedner.

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 81.

- ↑ Gulathingslov Art. 253 : "En su gata scal væra niu boga lengd."

- ↑ Heimskringla. Hákonar saga góða. Cape. 19th

- ↑ Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga helga. Cape. 234.

- ↑ Capelle p. 41.

- ↑ Saxo Grammaticus: Gesta Danorum 8th book chap. 8 : "quippe spicula arcuum ballistarumque tormentis excutere ..." (because they knew how to shoot arrows with bows and crossbows ...) German translation

- ↑ Königsspiegel chap. 17th

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 93.

- ↑ Saga Ólafs Tryggvasonar : "Finnr skaut, ok kom örin á boga Einars miðjan, í því bili er Einarr dró hit þriðja sinn bogann." (Finn shot, and the arrow hit the center of Einar's bow at the moment that the one Tied the bow for the third time. [Exercise Felix Niedner])

- ↑ In most editions there is “fiðrit” (pen) instead of “blaðit”. Fine Erichsen's translation in Thule Vol. 22 translates as “touched the feathers on one”. But Johan Fritzner: Ordbok over Det gamle norske Sprog. Vol. I. Kristiania 1896, ND. Oslo 1954 vol. 3 p. 579 corrected in "blaðit", also Falk (1914) p. 97.

- ↑ Þiðreks saga 75

- ↑ Falk (1914) pp. 95 ff.

- ↑ Königsspiegel chap. 37.

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 193 f.

- ↑ Capelle p. 39.So also Falk (1914) p. 155.

- ↑ Ploss, p. 11.

- ↑ Figure on p. 30. ( Memento from October 1, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 987 kB)

- ↑ Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga helga. Cape. 49: "valska hjálma". So it was obviously imported. The further description of the helmets and shields with inlaid gold crosses is a topos for decisive battles of holy kings.

- ↑ Krag p. 28.

- ↑ Egils saga chap. 27

- ↑ chap. 16.

- ↑ Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga helga. Cape. 227.

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 162.

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 169 with further references.

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 172.

- ↑ Heimskringla. Hákonar saga góða. Cape. 30th

- ↑ Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga helga. Cape. 49: "hringjabrynjur".

- ↑ Sigvald the Skald wrote about the course of the battle shortly after the battle. As eyewitness accounts, his verses can certainly claim credibility. Snorri included them in his report.

- ↑ Vice-Lavmand Eggert Olafsens og Land-Physici Biarne Povelsens Reise igiennem Iceland foranstalt af Videnskabernes Selskab i Kjøbenhavn . Sorø 1772. Vol. 2, p. 1035: “En meget beskadiget Ringebrynje forvares ogsaa paa painted Sted: that he toodobbelt, he, staaende af to og to flade Jærnringe føiede i verandre. Omkring he jibe the eengang saa tykt, og ikke viidere, end at den kan passe en middelmaadig Karl uden over Klæderne. ”(A badly damaged ring well is also kept at the place mentioned: It is double, that is, it consists of two and two flat iron rings, one inside the other. Around the neck it is suddenly so thick and no wider that it can fit a middle man over his clothes.)

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 184.

- ↑ Landslov chap. 3, 11 after the manuscript Cod. C 17, reproduced in Den nyere Lands-Lov , R. Keyser and PA Munch (eds.): Norges Gamle Love indtil 1387. Vol. 2. Christiania 1848. P. 42 fn. 5.

- ↑ Diplomatarium Norwegicum I, No. 321: "sex bonda skildir". Falk (1914) p. 127.

- ↑ [s: no: Side: Norges gamle Love indtil 1387 Bd. 1 101.jpg Gulathingslov ] No. 309. [s: no: Side: Norges gamle Love indtil 1387 Bd. 1 202.jpg Frostathingslov ] VII No. 15. Landslov of King Magnus lagabætir III, 11.

- ↑ Eirik's saga rauða chap. 10: When they saw the Skrælingers, they interpreted their behavior: "Vera kann, at þetta sé friðarmark, ok tökum skjöld hvítan ok berum at móti." (Maybe they are peace signs. Let's take a white sign and carry it towards them). When the Skrælingers came back later and became aggressive (chap. 11), they took red shields: "Þá tóku þeir Karlsefni rauðan skjöld ok báru at móti." (Karlefni's men took red shields and carried them towards them).

- ↑ R. Keyser and PA Munch (eds.): Norges Gamle Love indtil 1387. [s: no: Side: Norges gamle Love indtil 1387 vol. 1 335.jpg Bjarköret ] No. 173 on the criminal trial on the ship: “oc hafa sciolld rauðann uppi æ meðan þæir liggia við land. ”(…, and you have to pull up a red sign as long as you lie on land). The Swedish Uplandslag also knows the custom of pulling up a shield on the bow, in the section on 'man holiness' (homicides) No. 11 § 2. in the translation by Claudius Frh. Schwerin (1935).

- ↑ Landslov in: Keyser and PA Munch (eds.): Norges Gamle Love indtil 1387. Vol. 2. Christiania 1848. Chap. 3, 11: “Sa maðr er a til .vj. marka ueginna firi vttan klæðe sin. hann Skal eiga skiolld rauðan tuibyrðan… “(The man who has six weighed marks in addition to his clothes should have a red shield with two layers…).

- ↑ Eiríksdrápa Markús Skeggjasons via Erik Ejegod (1095–1103) Str. 6.

- ↑ Harald's saga Sigurðarsonar chap. 63

- ↑ Story of King Harald the Hard. Translation by Felix Niedner. It's about the Niså Battle of Harald against the Danish King Svend.

- ↑ Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga helga. Cape. 19th

- ^ Heimskringla, Harald's saga hárfagra. Cape. 18th

- ↑ Heimskringla. Ólaf's saga helga. Cape. 49 and 213.

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 143 with several references.

- ↑ "Rauðan skjöld hafði hann fyrir sér, ok var dregit á léo með gulli." (He held a red shield in front of him, on which a golden lion was painted.) Laxdæla saga chap. 21st

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 152.

- ^ Ordinance of King Erik Magnusson on trade and prices in Bergen of September 16, 1282 in Norges gamle Love indtil 1387 . Christiania 1849. Vol. 3 p. 15. According to another manuscript, he received eight Ertog for a battle shield .

- ↑ Hirðskrá chap. 35.

- ↑ Gretti's saga Ásmundarsonar chap. 40. Grettir fights against the predatory berserk Snækollur and irritates him: “Tók hann þá að grenja hátt og beit í skjaldarröndina og setti skjöldinn upp í munn sér og gein yfir hornii skjaldarins og lét allólmð. Grettir varpaði sér um völlinn. Og he hann kemur jafnfram hesti berserksins slær hann fæti sínum neðan undir skjaldarsporðinn svo hart að skjöldurinn gekk upp í munninn svo að rifnaði kjafturinn en kjálkarnir, loudly. put the shield in his mouth, opened his mouth over the corner of the shield and pretended to be very aggressive. Grettir ran across the square. When he came next to the berserker's horse, he kicked the bottom of the shield with his foot hard, so that the shield penetrated his mouth in such a way that it tore his mouth and the jaw fell on his chest.)

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 137.

- ↑ Falk (1914) p. 194 f. with further evidence of their occurrence.

- ↑ “At that time” - The saga takes place in the time of Olaf the Holy, around the year 1000.

- ^ A. Willemsen: Vikings on the Rhine. 800-1000. P. 144

literature

- Torsten Capelle : The Vikings. Culture and art history . Darmstadt 1986.

- Hjalmar Falk: Old Norse marine life . Special print from words and things . Vol. 4. Heidelberg 1912

- Hjalmar Falk: "Old Norse Weapons" In: Videnskabsselskapets Skrifter II . Kristiania 1914. No. 6.

- Den ældre Gulathings-Lov . In: Norges gamle love indtil 1387 . Vol. 1. Christiania 1846. pp. 3-118. Translation: The Right of Gulathing . Exercised by Rudolf Meißner. Germanic Rights Vol. 6. Weimar 1935.

- Snorri Sturluson: Heimskringla. (Ed. Bergljót S. Kristjánsdóttir and others). Reykjavík 1991, ISBN 9979-3-0309-3 (for the Icelandic citations). German: Snorris Königsbuch . Düsseldorf / Cologne 1965. Vol. 1–3.