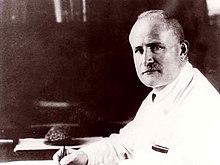

Hans Berger (physician)

Hans Berger (born May 21, 1873 in Neuses / Coburg ; † June 1, 1941 in Jena ) was a German neurologist and psychiatrist ; he was the developer of electroencephalography (EEG).

Life

Hans Berger was the son of the doctor Paul Friedrich Berger, director of the Coburg rural hospital . His grandfather was the poet and orientalist Friedrich Rückert . Berger attended the Casimirianum grammar school in Coburg, where he passed his Abitur in 1892 in all parts with "very good". Then he studied in Berlin initially mathematics and astronomy . He later switched to medicine , which led him from Berlin via Jena , where he became a member of the Arminia fraternity on the Burgkeller , to Würzburg and Kiel, finally back to Jena (1893-1897), where he also received his doctorate.

In 1897 Hans Berger began his medical work as an assistant at the psychiatric clinic under the direction of Otto Binswanger . His senior physician at that time was Theodor Draw . In 1901 he completed his habilitation with a thesis on the theory of blood circulation in the human skull , namely under the influence of drugs .

In 1912 he became senior physician and in 1919 Binswanger's successor as director of the psychiatric clinic and full professor.

In 1927/28 he held the office of rector of the Jena University . His rector's speech about localization in the cerebrum represents a kind of scientific creed.

Hans Berger was a supporting member of the SS and retired in 1938. This ended his work as a medical assessor at the Jena Higher Genetic Health Court (EGOG) in Jena, where he participated in the forced sterilizations in Nazi Germany. After the outbreak of the Second World War , he was once again provisionally assigned the management of the clinic in 1939 . When the Nazi racial hygienist Karl Astel asked him to work again at the EGOG in 1941, Berger agreed on March 4, 1941 ("I am very happy to work again as an assessor at the Hereditary Health Supreme Court in Jena and thank you for it.") but it never came to that.

On June 1, 1941 between 4:20 and 7 a.m., Hans Berger hanged himself in the south wing II of the Medical Clinic in Jena. He last lived in the sanatorium for the mentally ill in Bad Blankenburg , of which he was director. He was buried in Jena. In 1940 Berger was nominated three times for the Nobel Prize , with a total of 65 nominations, and the other two proposals in 1942 and 1947 were no longer evaluated due to his death.

Berger's path to the electroencephalogram

A formative experience in his youth motivated Berger to dedicate his life to looking into the soul of others. He writes:

“As a 19-year-old student, I had a serious accident during a military exercise in Würzburg and narrowly escaped certain death. Riding on the narrow edge of a steep ravine, I fell with the rearing and overturning horse into a battery driving in the depths of the ravine and came to rest under the wheel of a cannon. At the last moment the 6 horse-drawn gun stopped and I got away with it. This had happened in the morning hours of a fine spring day. On the evening of the same day I received a telegram from my father asking me how I am? It was the first and only time in my life that I received such a request. My eldest sister, with whom I was in particularly close fraternal relations, initiated this telegram request because she suddenly told my parents that she definitely knew that an accident had happened to me. My relatives lived in Coburg at the time. This is a spontaneous transmission of thoughts, in which I was active as the sender and the sister who was particularly close to me as the recipient at the moment of greatest danger, with certain death in mind. "

So it is an experience from the subject area of parapsychology , which stood at the cradle of electroencephalography.

In 1902 Hans Berger began experiments on the cerebral cortex of dogs and cats. He was always looking for ways to objectify the relationship between body and soul using physical methods. In terms of intellectual history, he can be seen as a representative of psychodynamics , which aims to bridge the gap between nature and spirit, see the following paragraph. Appreciation of Berger's merit .

In 1924 he began to develop a method for deriving "brain waves" from humans. This offered the possibility of deriving electrical activity from the intact cerebral cortex of a patient through a trepanation site . On July 6, 1924, Berger succeeded in registering the first reliable results - the first electroencephalogram was created.

After his success, Berger continued to experiment, had doubts, and started all over again. It was not until 1929 that he published his discovery. His work was entitled On the Electro-Cephalogram of Humans .

His groundbreaking discovery was not used for many years. It was not until 1934 that the English neurophysiologist Edgar Douglas Adrian came across Berger's work and recognized the scope of the discovery. He gave the alpha basic rhythm of the electrical brain activity the name Berger rhythm .

Appreciation of Berger's merit

Johann Kugler honors Berger, who belonged to the German Academy of Natural Scientists Leopoldina from 1937 , in the preface to his introduction to the investigation method of the EEG by writing:

"From Herbart and Lotze to Fechner , of Wundt to drag and Lehmann who psychophysics and Psychophysiology constantly deepens the relationship between brain and mind, between the physical and mental energy, and between objective observation and introspection. In his endeavor to find a solution to the mind-body problem - a solution that is perhaps impossible with the means of science of our time - Hans Berger examined the circulation, the temperature of the brain and the physical expression of mental states in order to find out Turning to not a few disappointments to the brain electricity that can be registered on the skull surface. Was Hans Berger an original thinker? For the professional philosophers and for the great neuropsychiatrists of his time, he was certainly not! Was he at least an electrophysiologist? His colleague Biedermann would have been the last to have recognized him as a successor to Du Bois-Reymond . So what was Berger then? We owe electroencephalography in humans to a witty, tenacious and methodical worker who was indifferent to the pomp and tumult of everyday life, a scientist who read Spinoza and Augustine on the Western Front in 1917 , who ceaselessly about psychic energy, its origin and pondered their transformations while maintaining a pure mind with a preference for rhymes, flowers, and stars; with the same passion he collected stones like EEG curves and wrote in 1921: 'One should love what one hopes and therefore only create what one loves.' What variety! May our young German friends pick up his 14 articles that are still excitingly up-to-date! They were reprinted in English translation in 1969 by Gloor .

Nevertheless, despite this unusual person, clinical electroencephalography first had to 'return' to Germany from the United States, Canada, Great Britain and the European continent; it came back standardized and electronized, but devoid of its intellectual sources and its noble possessions. "

The German Society for Clinical Neurophysiology has been awarding the Hans Berger Prize since 1960 . The Berger effect is named after Hans Berger and consists of a readiness reaction that can be recognized from the derivation of brain waves.

On May 23, 2000, the asteroid (12729) Berger, discovered on September 13, 1991, was named after Hans Berger.

See also

Fonts

- The human electrenkephalogram . In: Nova Acta Leopoldina , Vol. 6 (1938/39), No. 38, pp. 173-309, ISSN 0369-5034

- Psyche . Gustav Fischer, Jena 1940.

- Psychophysiology in 12 lectures . Fischer Verlag, Jena 1921.

- Experimental Physiology . Springer, Berlin 1937 (Handbook of Neurology / A; 2).

literature

- Peter Kaupp: Berger, Hans . In: Ders .: From Aldenhoven to Zittler. Members of the Arminia fraternity on the Burgkeller-Jena who have emerged in public life over the past 100 years . Self-published, Dieburg 2000.

Web links

- Literature by and about Hans Berger in the catalog of the German National Library

- History. Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, archived from the original on October 24, 2010 ; Retrieved December 18, 2011 .

- From the facilities / 200 years of Jena mental hospital. In: Clinic magazine. University of Jena, archived from the original on June 11, 2007 ; Retrieved December 18, 2011 .

- Historical EEG recordings on the website of the Jena Clinic for Neurology

Individual evidence

- ^ Ernst Klee : The dictionary of persons on the Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945 . Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Second updated edition, Frankfurt am Main 2005, p. 41.

- ↑ Dirk Preuss, Uwe Hossfeld, Olaf Breidbach: Anthropologie after Haeckel . Franz Steiner Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-515-08902-0 , p. 136

- ↑ Harald Sandner: Coburg in the 20th century. The chronicle of the city of Coburg and the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha from January 1, 1900 to December 31, 1999 - from the "good old days" to the dawn of the 21st century. Against forgetting . Verlagsanstalt Neue Presse, Coburg 2002, ISBN 3-00-006732-9 , p. 168

- ↑ U.-J. Gerhard, A. Schönberg, B. Blanz: "Had Berger lived through the end of the Second World War - he would certainly have been a candidate for the Nobel Prize" - Hans Berger and the legend of the Nobel Prize; A contribution to the 200th anniversary of the founding of the Jena Psychiatric Clinic . In: Advances in Neurology - Psychiatry. 73, 2005, p. 156, doi: 10.1055 / s-2004-830086

- ↑ Hans Berger: About the human electrenkephalogram . In: Archives for Psychiatry and Nervous Diseases . tape 87 , no. 1 . Springer, 1929, ISSN 0003-9373 , p. 527-570 , doi : 10.1007 / BF01797193 .

- ^ Johann Kugler : Electroencephalography in clinic and practice. An introduction . 3. Edition. Thieme, Stuttgart 1981, ISBN 3-13-367903-1 , p. V .

- ↑ Minor Planet Circ. 40709

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Berger, Hans |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German neurologist and psychiatrist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 21, 1873 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | News |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 1, 1941 |

| Place of death | Jena |