Fritz Behn

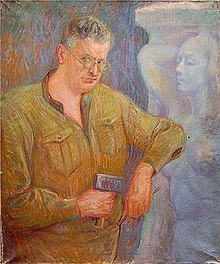

Fritz Behn (born June 16, 1878 in Klein Grabow , † January 26, 1970 in Munich ; full name Max Adolf Friedrich Behn ) was a German sculptor who achieved importance primarily with his African animal sculptures.

life and work

Until the end of the First World War in 1918

Fritz Behn was born on his parents' estate in Klein Grabow near Güstrow . He was a grandson of Lübeck's mayor Heinrich Theodor Behn and great-grandson of Lübeck doctor Georg Heinrich Behn .

After attending the Nikolaischule in Leipzig, Behn moved to the Katharineum in Lübeck in 1893 , where he graduated from high school at Easter 1898. From 1898 to 1900 he attended the Munich Art Academy , first for a semester in the nature class and then in the sculpture class . There he was a student of Wilhelm von Rümann . At the age of 22, Behn started his own business as a sculptor. He joined the circle around the sculptor Adolf von Hildebrand and became a member of the Munich Secession .

His artistic talent was already evident in Leipzig. At the age of fourteen, he successfully submitted a design for an Old Shatterhand memorial to a competition for the magazine “ Der Gute Kamerad ”. In Munich he was one of the early members of the German Association of Artists and participated in its first exhibition in 1904 in the Munich Royal Exhibition Building on Königsplatz with a bronze bust of the Belgian graphic artist Georges-Marie Baltus (1874-1967), as well as several plaques and a Goethe relief .

In 1905, 1907 and 1909 Behn was represented at the Venice Biennale. During these years, apart from grave monuments and portrait busts, a whole series of works were created in public space: Schiller fountain in Essen (1905), group of tritons at the building of the Aquarium Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn in Naples / Italy (1906), Johannes fountain in Lübeck ( 1907), Prinzregent-Luitpold-Brunnen in Ansbach (1908), group “Kraft” in Bavariapark in Munich (1908), Wolfsbrunnen in Schloss Wolfsbrunn in Hartenstein (1911/12), figure of St. Michael in knight armor on the facade of the palace Sigmaringen (before 1912), Prinzregent-Ludwig-Brunnen in Murnau am Staffelsee (1913).

In 1907/08 and 1909/10, two trips of several months to the colony of German East Africa followed . He made anatomical drawings and plaster casts of the big game he killed on his travels, which he brought to Munich and set up in his studio. Under the impression of his travels to Africa, large and small sculptures of lions, leopards, antelopes, buffalos, rhinos and elephants were created in the following years. These works are among the most important works of his oeuvre. Behn also found international recognition with his African animal sculptures. The art historian Kineton Parkes wrote in 1929: "He is acknowledged as the leading Tierplastiker of Germany, as Barye was of France and JM Swan of England." (Parkes, Kineton: The Animal Sculpture of Fritz Behn. In: The American Magazine of Art. Vol. 20, No. 1, January 1929, pp. 338–342, here: p. 341.) In 1917 Behn published his book “'Haizuru…' A sculptor in Africa”.

Since 1911 a member of the German Colonial Society, Behn was a staunch supporter of colonial rule. He represented a colonialist worldview that went hand in hand with racist views. The white man is either “master” in the colonies or not at all. The colonial question is not one of human rights, equality, freedom or morality. The German Empire (“we”) would not want colonies so that the eyes of blacks would shine, “but because we have to expand.” He decidedly rejected “Racial mixes” in the publication entitled “On the Question of Mixed Marriage”. He campaigned for nature and game protection in the colonies.

Prince Regent Luitpold of Bavaria awarded Fritz Behn the title of "Royal Bavarian Professor" for life in 1910. In the period before and after the First World War, he received appointments at the Technical University of Stuttgart, the Technical University of Munich and the Weimar Art Academy. He does not accept any of the calls. In the winter of 1911/1912 he went to Paris for a longer study trip and visited the French sculptor Auguste Rodin . Further trips took him to Italy and London.

In 1913 Behn won the tender for a colonial war memorial to be erected in Berlin "for the Germans who remained in battle on non-European soil". Behn's design envisaged the figure of a monumental, raised African elephant as the main motif of the monument. However, the draft fell through with criticism and the public. The colonial war memorial projected by resolution of the Reichstag, the Bundesrat and with the approval and on behalf of the Reich Chancellor appeared with a nationwide claim to validity and effectiveness. It was to become the central colonial monument on German soil. However, the Berlin monument project was not carried out as a result of the outbreak of the First World War.

On January 17, 1913, the "Collection II" exhibition opened at the Thannhauser Gallery in Munich, where sculptures by Fritz Behn were shown alongside pictures by Franz Marc. Thomas Mann published his essay “For Fritz Behn”.

When the war broke out at the end of July 1914, he volunteered. It was first used on the Western Front . Because he developed lung disease, he was transferred to the 6th Army headquarters in Lille in mid-March 1915. Behn's demobilization took place on January 22nd, 1916. When he returned to Munich, he resumed his sculptural work. At the Franz Marc Memorial Exhibition, which took place in the rooms of the New Secession in Munich in 1916, works by Fritz Behn, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Edvard Munch and Hermann Huber were shown alongside paintings by Franz Marc. Presumably in the spring of 1917 he was assigned to a longer mission in the Aegean Sea. After a stay in a hospital in Constantinople, he returned to Germany in the summer of 1918. On behalf of the War Graves Commission, he worked briefly as a consultant at military cemeteries in Belgium and northern France. Since the beginning of the war, he has represented extremely nationalist and anti-democratic positions.

Weimar Republic

At the end of 1919 Behn moved his residence to Scharnitz in the Karwendel Mountains, where he owned a country house; He kept his Munich studio. In the first post-war years, Behn moved in both conservative and right-wing extremist circles. He represented monarchist-nationalist and anti-democratic positions. For a time he was president of the Bavarian Order Bloc, which he co-founded at the end of March 1920, an association of ethnic-nationalist organizations. He also positioned himself on the side of the extreme right in numerous magazine articles. In 1920 he published the brochure “Freedom”. Political marginal notes ”. As early as 1920, Behn was involved in the Nazi circle. The early membership in the NSDAP, which he himself handed down and which was denied after 1945, cannot be proven in the relevant archive sources. (See Joachim Zeller: Wilde Moderne. The sculptor Fritz Behn (1878–1970), Berlin 2016, p. 66.) In 1923 he is said to have also joined the SA. Contacts with Adolf Hitler can be proven since 1921. In the following years he turned away from the NSDAP again, but towards the end of the 1920s he was again benevolent towards the NS movement due to its electoral successes.

He also expressed his political preferences in public with art-political judgments. When in 1921 a figure of Christ by the expressionist Ludwig Gies was hung up in Lübeck Cathedral on a trial basis , Behn made derogatory comments about the wooden sculpture, which was torn down by strangers in 1922 and shown in the 1937 exhibition “Degenerate Art” as an example of “cultural Bolshevik” art.

In 1925, textile entrepreneur Otto Pongs donated 10,000 marks in Viersen to erect a memorial to the “memory of the fallen sons of our city”. The sum was increased by further donations. The foundation stone was laid on May 9, 1926, the first Sunday after the Belgian occupation forces withdrew . The Monument Committee decided on a design by Behn after visiting his studio in Munich. Based on the Pietà motif , the design, created in previous years, shows a seated mourning mother with her dead son on her lap. The shell limestone monument is four meters high. Since the portrayal of the son as a nude figure met with criticism, the warrior figure was given a loincloth. The monument was inaugurated on August 9, 1926. The city of Viersen rated the monument in 2005 as follows: “The war memorial in this version is a typical example of its time, in which memorials are understood as symbols of self-sacrifice and heroism and as an appeal to give everything“ for the fatherland ”. [...] A war memorial should comfort the relatives, give death a meaning and oblige the survivors to follow the example of the victims. The speeches held for the laying of the foundation stone and the unveiling of the Viersen war memorial reflect the zeitgeist. Nevertheless, it is a markedly unheroic monument that focuses on grief and suffering by showing a dead soldier and a grieving mother. "

Due to the difficult financial situation as a result of inflation and the lack of orders, Fritz Behn lived in Buenos Aires / Argentina between 1923 and 1925. In the two years he mainly received orders for portrait busts and tombs. The earning potential was so good that he can still commission the construction of a new studio house in Munich from Argentina. After his return to Munich, he moved into his newly built apartment and studio at Kunigundenstrasse 28 in Schwabing. Since the end of the First World War, and then especially after 1925, the industrial manager and economic functionary Paul Reusch has acted as a patron of Fritz Behn. The "Ruhrbaron" acquired works by Behn and brokered a number of orders from large-scale industry for the erection of warriors' and personal memorials. A large number of animal sculptures continued to be made. Behn has been friends with the cultural philosopher Oswald Spengler since 1926. In the 1920s, Spengler was regarded as the gray eminence of the southern German hostility towards the republic and the intellectual cue for the so-called “conservative revolution”.

Even when he was no longer active in Lübeck, he often returned there. Like Thomas Mann from Munich and Hermann Abendroth , both of whom, like him in Lübeck, had once been sponsored by Ida Boy-Ed , Behn was one of the invited guests to the city's 700th anniversary in 1926. The high point of the festival on June 6, 1926 coincided with Thomas Mann's 51st birthday. Their former patron invited them to their apartment at the castle gate from where they watched the parade . They then celebrated Mann's birthday.

Elected President of the Munich Artists' Cooperative in 1927 , Behn directed the annual exhibition in the Munich Glass Palace. In this position, Behn ensured that the title of professor was awarded to the national socialist painter Edmund Steppes, who wrote in the Völkischer Beobachter in 1923 against Alfred Rosenberg's positive assessment of Expressionism and continued to write there.

In 1927 he himself became an employee of the visual arts in the features section of the Völkischer Beobachter . He was predestined for this by the fact that he “as a declared anti-modernist” fought against the avant-garde currents of the 1920s and, as he reported in the Völkischer Beobachter in 1931 , “the chaos of cultural decomposition”.

At that time, Behn, who had designed some colonial sculptures for Munich, such as a lion figure in Hellabrunn Zoo, was a welcome lecturer at the “Warriors of German Colonial Troops Munich”, whose honorary chairman was the right-wing multifunctional Franz Ritter von Epp . The German Colonial Society paid attention to Behn in its publications, for example on the occasion of his birthday: Art in the service of the colonial idea. Fritz Behn on his 50th birthday in your magazine.

In 1928 Behn was one of the initiators of the National Socialist Combat League for German Culture , which intended to represent and defend “the values of German character”, “moral and soldier values” and to provide information about the connections between race, culture and art. Membership in the Kampfbund required membership in the NSDAP. Behn's political stance found expression in his artistic work, for example in numerous monuments of military commemorative politics and culture (war memorials), in the Bremen Colonial Memorial (1932), in a bronze bust for the old party member in honor of the Austrian NSDAP and Hitler admirer Heinrich von Srbik , in the larger-than-life bronze sower (1925), which was shown in an exhibition at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna in 1940, or a woman's nude in stone .

At the altar of the church of Ivenack Castle , a war memorial from the Behnsche workshop was inaugurated in 1929, donated by the Count couple Plessen, which shows a soldier praying on the defeated enemy animal and thus implements the idea of an army undefeated in the field. Both the implementation of the stab in the back and the depiction of the enemy as an animal are unusual for German war memorials in 1929.

The “Reich Colonial Memorial” designed by Behn as the central monument of the Reich colonial movement, here the German Colonial Society, for the overseas port city of Bremen and completed in 1931 sparked a controversial local discussion, so that it could not be inaugurated until 1932. It showed a larger than life elephant and, among other things, an honoring portrait of the extremely controversial colonial officer Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck , who led the genocidal suppression of the Herero and Nama uprisings in German South West Africa (1904–1907) and the right-wing extremist Kapp Putsch 1920 had been involved against the constitutional government. Below the elephant was a crypt in which the list of names of around 1,500 German colonial soldiers who had not survived the world war was kept. The names of the German colonies lost with the Treaty of Versailles were written on plaques on the sides . The design came from Behn.

Another trip to Africa followed in 1931/1932. Behn was meanwhile a "star of the colonialist movement" ( Wolfgang Schieder ), to which his Africa books also contributed.

In 1931 he made a Bismarck statue for Munich on behalf of the founder, Paul Reusch , heavy industrialist and founder of the secret " Ruhrlade " . The Ruhrlade had been supporting the NSDAP with large sums since 1931, and Reusch advocated a transfer of power to this party. Bismarck is depicted as a mythical hero, as a watchful guardian of the empire based on the model of the Hamburg Bismarck monument (built 1901–1906).

There was a dispute about the location at the Deutsches Museum , in which Behn was defeated. Oskar von Miller , founder of the Deutsches Museum, refused to place the monument on the museum's premises, because Bismarck was important as the founder of the empire, but technology and science were only indirectly promoted by him. The Völkischer Beobachter attacked Miller as a party member of the “councilor government ” and “internationalist” who did not appreciate a German statesman. The mighty Bismarck statue still stands on urban soil, not on museum grounds. Behn tried to push through another project in Munich, a well for the square at Sendlinger Tor, which would have required larger and expensive construction work. Behn only wanted - according to the mayor - to cause a scandal; as a result, the city building committee unanimously rejected the "National Socialist demands". Behn is a talented artist, but also a brutal man.

In 1931, on the occasion of Wilhelm Raabe's 100th birthday, a Wilhelm Raabe fountain was inaugurated in Braunschweig , the design of which was done by Behn. The brain behind the fountain project was Theodor Abitz-Schultze (1878–1963), chairman of the Munich-based “Raabe Foundation”, founded in 1931, whose other board members were Börries von Münchhausen and Werner Jansen . The latter two became exponents of Nazi literary politics. The call for the building of monuments was supported by a large number of well-known writers, some of whom explicitly did not belong to the ethnic- national socialist spectrum, such as Thomas Mann , Fritz von Unruh , Heinrich Vogeler . Abitz-Schultze had also established Behn as a designer. According to Horst Denkler , Behn's Raabe monument is characterized by “aberrations of taste” and “heroically poetically kitsched” representations. Raabe was stylized on the memorial as a knightly unicorn lover.

The memorial in Speyer for two of the attackers on the government of the Palatinate separatists around Franz Josef Heinz , Franz Hellinger and Ferdinand Wiesmann , who were both venerated by right-wing extremists as "martyrs of the national cause", was designed by Behn in 1931. The order for the murder of the separatists had been given by the Bavarian government, the group of assassins was led by Edgar Julius Jung .

From 1933 during the National Socialism

He had his own relationship with Benito Mussolini , the leader of the Italian fascists. In this context, Schieder rates Behn as a "philo-fascist thinker" and as an "uncritical admirer of the ' Duce '", by whom Behn was invited to audiences several times in the summer of 1934. Behn portrayed Mussolini with “the greatest possible admiration” as a “great noble animal, charged with energy and strength” while making a martial porphyry bust that was created after his visit to Rome. He published a book on this in 1934 ("Bei Mussolini - Eine Bildnisstudie"), in which he also articulated himself as an anti-Semite . He promised himself, among other things, “also” from Mussolini “a precise answer” to the “Jewish question”, “because the Jews also seem to be gathering there [in Italy]”, which was to be combated. In 1937 a further statement by Behn appeared in the Library of Entertainment and Knowledge of the Union Deutsche Verlagsgesellschaft under the National Socialist publisher Georg von Holtzbrinck : “At Mussolini”.

In 1937 Behn created an oversized relief of the namesake with martial facial features for the newly built Luther Church of the Lübeck Luther parish. The pastor of the commissioning community had been "a staunch National Socialist and belonged to the anti-Semitic Association for the German Church " since the 1920s . Before Behn, the völkisch-national-socialist visual artist Erich Klahn, who was also closely connected to Lübeck, had already worked there on the municipal commission.

In April and May 1937 Behn was represented in the exhibition “German Architecture and German Sculpture” of the Vienna Secession , led by the National Socialist architect Alexander Popp , which offered an extensive presentation of the “National Socialist conception of art” in Austria (Susanne Panholzer-Hehenberger: “The propaganda function was obviously. ”) Like the other German contributors, he was also appointed a corresponding member of the Secession.

The National Socialist monthly magazines published in 1938 in five editions full-page, black-and-white art prints with Behn's works, including three paintings by African Travel, a "Moose in the Mist" and a photo of a sculpture entitled "Workers figure". In the December issue followed an article Tatmensch und Künstler: Fritz Behn, which in turn was art prints a. a. of two African paintings, plus a picture of the MAN memorial, a photo of the artist and photos of numerous animal sculptures. Behn is one of the “Nordic and German people” for the NS monthly. He should be mentioned in a row with Goethe and Nietzsche . The booklets are particularly impressed by his heroism: “In his African animal sculpture, Behn created the type of a new heroic monumentality that was no longer conceived in the studio, but based on experience and won.” The African big game corresponds to the world of experience of the ancient Europeans. He also shows “German game” in a “heroic, combative attitude”. Behn is not just an animal sculptor, his memorials for the fallen of the First World War are shaped by his “front-line combatant experience” and in the bust for Hans Pfitzner , an irrepressible fighter against “alien” music, one heroic man of action inspires another.

From 1937 to 1940 he was represented at the Great German Art Exhibitions in the House of German Art in Munich with fifteen animal sculptures and three figurative sculptures (1938: worker figure and walking girl and 1939: sower ).

After the annexation of Austria , the Cubism- oriented Albert Bechtold was removed by the National Socialists for political reasons from the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna , where he headed the sculpture class, and initially replaced by a provisional leadership appointed by the NSDAP regional leadership. Behn was first honored with an exhibition in January 1939, but not yet appointed. In 1940 Behn was appointed head sculptor and director of the academy, a position that he held as a professor until his dismissal with the end of National Socialism. Behn had been proposed as the successor of Bechtold with the argument that he "took a leading position in party life". Behn was counted to the "environment" of the later Gauleiter of Vienna Baldur von Schirach .

For the centenary in 1940, the MAN company in Augsburg erected a statue of its founder Heinrich von Buz , which Fritz Behn designed.

In August 1941 Behn was a guest at the Salzburg Festival at the invitation of the Salzburg Gauleiter Friedrich Rainer .

In 1941/1942 he was allowed to take part in the anniversary exhibition of the Society of Fine Artists Vienna in the Künstlerhaus on the occasion of its 80th anniversary, which showed the "probably most representative cross-section, especially for sculpture" of Nazi art.

In 1942, Schirach commissioned Behn to create a bust of the Nazi-affiliated composer Richard Strauss , which is now owned by the State of Austria.In 1943 and 1944, he acquired further busts of musicians from Behn: Hans Knappertsbusch , Wilhelm Furtwängler and Edwin Fischer .

In 1943, Behn and Asmus Jessen , Erich Klahn and Hans Heitmann received the Emanuel Geibel Prize from the city of Lübeck, which was awarded for the first and last time . The price proposals of the Lübeck administration required the approval of the NSDAP, which they received. In the same year Adolf Hitler awarded him the Goethe Medal for Art and Science .

At times Behn was also responsible for the magazine Kulturdienst der NS-Kulturgemeinde. Behn was on the God-gifted list of the regime's most important visual artists.

Behn also emerged with various writings during National Socialism. In 1934 he published Bei Mussolini and 1935 German game in the German forest . His friend Georg Escherich , founder of the right-wing terrorist " Orgesch ", wrote the foreword for this book .

After 1945

In June 1945, Behn was removed from office at the Vienna Art Academy by the Vienna State Office for Public Enlightenment, Teaching, Education and Cultural Affairs. The sculptor Fritz Wotruba, who had returned from exile in Switzerland, became his successor. The Munich Spruchkammer classified Behn in group 5 of the exonerated. Behn complained that Fritz Wotruba and others would stamp him as a “Nazi sculptor” with the help of a “left press”. However, he was in opposition to the Nazi regime and had not received any orders from the Nazi regime. Fritz Behn lived penniless in his country house in Ehrwald (Tyrol) and ran a sculpture school there. In 1951 he moved back to Munich. He receives a pension from the Federal Republic of Germany.

Because of its proximity to the Nazi regime, Behn was initially no longer justifiable in the West German cultural scene. He now manufactured u. a. Portraits of Maria Callas , Ricarda Huch , Albert Schweitzer , Theodor Heuss , Pius XII. and by Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck .

In June 1956, a Behn exhibition opened at the Technical University of Munich with more than 140 sculptures and drawings. No other of the art institutions in Munich mentioned by Behn had been willing to provide him with premises.

In 1960 Behn made the large-scale sculpture of a kudu for Windhoek , the capital of the territory occupied by South Africa, the former colony " German South West Africa ".

In 1968 he was awarded the Lübeck Senate Badge on his 90th birthday .

In 1969 the Albert Schweitzer monument, which Behn had completed a few years earlier, was inaugurated in Günsbach in Alsace.

Fritz Behn died on January 26, 1970 in his studio apartment in Munich at Ungererstraße 25. He was buried in the Nordfriedhof.

In 1973 a Fritz Behn Museum was opened in Bad Dürrheim (Black Forest) on the initiative of Fritz Kiehn , a former member of the NSDAP Reichstag with the honorary title “Old Party Member” . Robert von Schirach, son of the Nazi youth leader Baldur von Schirach and a large hunting leader in Tanganyika , arranged the contact between the two. By paying a pension to Behn, Kiehn had secured the rights to his works. Kiehn procured further sculptures for his hometown Trossingen. At the opening, Kiehn declared Behn to be one of the most important German sculptors of the 20th century. Animal sculptures and other sculptures by Behn were also set up in the Bad Dürrheim spa gardens.

In 2006 the Fritz Behn Museum in Bad Dürrheim was closed. The city terminated the contract between the Kiehn community of heirs in October 2008 after the museum had hardly any visitors in 2004. In 2007 the works of the now closed Fritz Behn Museum were auctioned off at the Munich auction house Neumeister. Most of the works ended up in the private collection of Karl H. Knauf in Berlin.

In the more recent art historiography, Fritz Behn's assessment is ambiguous: On the one hand, he could be counted among the important animaliers of the 20th century with his animal sculptures. On the other hand, the politicizing sculptor Behn had discredited himself and his life's work through his collaboration on the extreme right - not to mention his colonial mastery of the early years - and put himself on the sidelines.

Monuments and individual sculptures (selection)

Johannes-Brunnen, Johanneum

1907; LübeckFelix Mottl's grave

before 1912Prince Regent Ludwig Fountain

Murnau am Staffelsee (1913)Dying Warrior (1919; memorial erected in 1920 for Hans Küstermann , Behn's brother-in-law, at the Lübeck Ehrenfriedhof

Lübeck)Striding Antelope

1925; Lübeck, near HolstentorFallen Memorial to 1914/18 with the motif "undefeated in the field" (cf. stab in the back legend ) (before 1929; castle church in Ivenack , Mecklenburg)

Bismarck Memorial

1931; MunichReichskolonialdenkmal (1932) and anti-colonial monument

1989; BremenPanther, school garden

1934; LübeckOrangutan from 1935 in the Berlin Zoological Garden

Martin Luther

rebuilt Luther Church in

1937; LübeckMourners (after 1948); Leipzig, Südfriedhof , tomb of the Curt Berger family (son-in-law of the founder of Mey & Edlich )

- Genius of death , tomb Daniel Schutte (1901; Hamburg, Ohlsdorfer Friedhof)

- Seated boy , Grabfeld Cohen family (1901; Hamburg, Ohlsdorfer Friedhof)

- Winged Chronos , Grabfeld Held family (1904; Hamburg, Ohlsdorfer Friedhof)

- Brahms- Herme (around 1906)

- John the Baptist, fountain in the school yard of the Johanneum in Lübeck (1907)

- Schiller fountain in the Essen city forest (1907/1908)

- Competition draft for a Bismarck national monument on the Elisenhöhe near Bingerbrück (1910; together with the architect Paul Bonatz; not awarded a prize).

- Young man with cornucopia , Sieveking tomb, Hamburg Ohlsdorfer Friedhof (1911) (Ohlsdorf cat. No. 586)

- Standing Maasai , bronze sculpture (1910).

- Bust of State Secretary Solf , bronze sculpture (before 1912)

- The dancer Nijinski , porcelain figure (1912)

- Diana with jumping antelope in Cologne (1916)

- Dying warrior , Ehrenfriedhof (Lübeck) , Travemünder Allee (1919)

- Panther sculpture , Südpark, Cologne-Marienburg (around 1920)

- Sower , bronze sculpture in Ehrwald (1925)

- Striding antelope near the Holsten Gate in Lübeck (around 1925)

- War memorial in the old town garden in Viersen (1926)

- Project Reichs-Kolonial-Ehrenmal near the Wartburg , not realized (1930)

- Colonial memorial for Bremen (1932), see also Hermann-Böse-Gymnasium

- Animal sculptures in Lübeck's Eschenburg-Park Lübeck

- Bismarck statue at the Deutsches Museum in Munich (1931)

- Hissing leopard , Behnhausgarten Lübeck (1932)

- Panther in the Lübeck School Garden (1934)

- Reh , at the Lübeck-Schlutup City Library (around 1934)

- Roaring deer (undated)

- Benito Mussolini (1934)

- Orangutan , granite sculpture in the Berlin Zoological Garden (1935)

- Martin Luther , Wall sculpture made of shell limestone on the Luther Church in Lübeck (1937)

- Portrait bust of Wilhelm Furtwängler in the Austrian Gallery Belvedere (undated)

- Portrait bust of Karl Hoppenstedt (first President of the Lübeck Regional Court) in the hallway of the session wing of the Lübeck Regional Court (undated)

- Portrait bust of Hans Knappertsbusch in the Austrian Gallery Belvedere (undated)

- Porphyry bust of Benito Mussolini (1934)

- Portrait bust of Hans Pfitzner in the Austrian Gallery Belvedere (undated)

- Bronze bust of Heinrich von Srbik (undated)

- Portrait of Richard Strauss in the Fritz Kiehn Collection (undated)

- Bust of Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck (1960)

- Kudu. Bronze sculpture on a brick base on Independence Avenue (then Kaiser St.) in Windhoek , Namibia (1960)

Fonts

- Sketches from the Heiligen-Geist Hospital in Lübeck (14 panels based on watercolors and oil paintings in fan printing. 14 text panels in facsimile printing.) Ernesto Tesdorpf, Lübeck 1899.

- Conservation of nature and wild murder in German East Africa - a cultural scandal. 1911 Naturwissenschaftliche Wochenschrift, 10 (51), pp. 801–807.

- On the question of mixed marriages. In: Süddeutsche Monatshefte. 10/1, 1912/13, p. 156 ff.

- African visions. 14 lithographs. Piper, Munich 1914.

- "Haizuru ..." A sculptor in Africa (with 16 drawings and 100 photographs by the author) G. Müller, Munich 1917.

- Americanism in Germany. In: Süddeutsche Monatshefte. H. 27 (1919), p. 672 ff.

- "Freedom". Political marginal remarks. Riehn, Munich 1920. LaL 4

- Art and tendency , with an afterword by Wilhelm Weiß . In: Völkischer Beobachter. No. 94, April 24, 1929.

- Kwa Heri, Africa! Thoughts in the tent (with 16 drawings by the author) Cotta, Stuttgart / Berlin 1933 LaL 4

- At Mussolini. A portrait study. Cotta, Stuttgart / Berlin 1934 LaL 1

- Animals. (Foreword by Ludwig Heck ) Cotta, Stuttgart / Berlin 1934.

- German game in the German forest. Cotta, Stuttgart 1935 (with 20 drawings and a portrait of Behn).

- Contribution to: Oswald Spengler in memory. Edited by Paul Reusch , edited by Richard Korherr , Nördlingen 1938, DNB 57866934X / 04 (title page with a bust of Spengler von Behn).

The writings marked with LaL are writings that are listed in the " List of literature to be sorted out " of the Soviet occupation zone . The digits denote the corresponding individual title in which Behn's work is listed.

literature

- Reichs Handbuch der Deutschen Gesellschaft - The handbook of personalities in words and pictures. First volume, Deutscher Wirtschaftsverlag, Berlin 1930, ISBN 3-598-30664-4 .

- Klaus W. Jonas: The sculptor Fritz Behn. In: The car . Year 2000, pp. 190-214.

- Barbara Leisner, Ellen Thormann, Heiko KL Schulze : The Hamburg main cemetery Ohlsdorf. History and tombs. Volume 2, catalog, Hamburg Christians Verlag 1990.

- Hugo Schmidt (Ed.): Fritz Behn as an animal sculptor (= Hugo Schmidts Kunstbreviere. Volume 1). Hugo Schmidt, Munich 1922.

- Sabine Spindler: Fritz Behn. In: Collectors Journal. May 2014, pp. 30–38 ( denes-szy.com ( Memento from June 16, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) [PDF; 980 kB]).

- Joachim Zeller : Wild Modernism. The sculptor Fritz Behn (1878–1970). Nicolai Verlag, Berlin 2016.

- Joachim Zeller: Art and Colonialism. The image of Africa by the sculptor Fritz Behn. In: Yearbook for European Overseas History. 16 (2016), Wiesbaden 2016, pp. 135–158.

- Jan Zimmermann : "I had a lot on my mind, what I would like to say to the youth on this occasion". Thomas Mann's participation in the 400th anniversary of the Katharineum in Lübeck in September 1931. In: Britta Dittmann, Thomas Rütten, Hans Wißkirchen, Jan Zimmermann (eds.): "Your very devoted Thomas Mann". Autographs from the archive of the Buddenbrookhaus. Schmidt-Römhild, Lübeck 2006.

Web links

- Literature by and about Fritz Behn in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Fritz Behn in the German Digital Library

- Search for "Fritz Behn" in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Database of the Central Institute for Art History, German Historical Museum and House of Art with information on all works of art exhibited at the major German art exhibitions

- The war memorial in the old town garden in Viersen

Individual evidence

- ^ Hermann Genzken: The Abitur graduates of the Katharineum in Lübeck (grammar school and secondary school) from Easter 1807 to 1907. Borchers, Lübeck 1907, No. 1083, urn : nbn: de: hbz: 061: 1-305545 . Fellow high school graduates were Gustav Radbruch , Hermann Link , Gustav Brecht and Friedrich Brutzer .

- ↑ 01861 Fritz Behn, register book 1884–1920 .

- ↑ 01888 Fritz Behn, register book 1884–1920 .

- ↑ Joachim Biermann: The sculptor Fritz Behn as a young May reader. In: Communications from the Karl May Society . No. 157, September 2008, pp. 35–37 ( karl-may-gesellschaft.de [PDF; 6.9 MB; with illustration]).

- ^ Exhibition catalog X. Exhibition of the Munich Secession: The German Association of Artists (in connection with an exhibition of exquisite products of the arts in the craft). Publishing house F. Bruckmann, Munich 1904 (p. 37: Behn, Fritz, Munich. Catalog No. 178: G. M. Baltus, bronze bust; six bronze plaques; Goethe relief in bronze, gilded ).

- ^ Fritz Behn: On the question of mixed marriages. In: Süddeutsche Monatshefte . H. 1/11, year 1911/12, p. 155 f.

- ↑ Birthe Kundrus : Modern Imperialists. The empire in the mirror of its colonies. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar 2003, p. 224.

- ↑ Matthias Berg, Karl Alexander von Müller: Historians for National Socialism. Göttingen 2014, p. 81.

- ↑ Arnold Brecht : Up close. Memoirs 1884–1927. Memoirs Volume I, Stuttgart 1966, p. 334 f.

-

↑ Hansjörg Buss: “Entjudete” church: The Lübeck regional church between Christian anti-Judaism and ethnic anti-Semitism (1918–1950) Paderborn / Munich / Vienna / Zurich 2011, p. 128;

Sculptor Gies between scandal and statecraft . In: Der Spiegel . No. 11 , 1990, pp. 259 ( Online - Mar. 12, 1990 ). - ↑ City Guide Viersen, Chronicle (PDF; 4.4 MB). In viersen.de, accessed on October 6, 2019.

- ↑ Viersen war memorial. In: viersen.de, accessed on June 7, 2016.

- ↑ Rubric: To our pictures. In: From Lübeck's towers . Volume 36, No. 14, edition of June 26, 1926, p. 60.

- ^ A b Andreas Burmester : The struggle for art: Max Doerner and his Reichsinstitut für Maltechnik. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar, 2016, p. 773.

- ↑ See Andreas Zoller: The landscape painter Edmund Steppes (1873–1968) and his vision of a “German painting”. Braunschweig 1999, p. 154 f.

- ↑ Andreas Zoller: The landscape painter Edmund Steppes (1873-1968) and his vision of a "German painting". Dissertation, p. 177, DNB 957860471/34 .

- ^ Joachim Zeller: Munich colonial art. The sculptor Fritz Behn ( muc.postkolonial.net [PDF; 495 kB]).

- ^ Martin W. Rühlemann: Bavaria in China. The myths of the colonial war 1900/01 and the Munich warriors of German colonial troops. 2012.

- ↑ Art in the service of the colonial idea. Fritz Behn on his 50th birthday. In: Der Kolonialdeutsche 1928 from: PDF; 495 kB; Reference .

- ^ Matthias Rösch: The Munich NSDAP 1925-1933. An investigation into the internal structure of the NSDAP in the Weimar Republic. Munich 2002, p. 136.

- ^ Susanne Panholzer-Hehenberger: The image of man in sculpture in Austria between 1938 and 1945. Diploma thesis, University of Vienna. Vienna 2008, p. 151 ( PDF; 764 kB ).

- ↑ a b See zugspitzarena.com: sculptures and paintings by Prof. Behn .

- ↑ a b Loretana de Libero: Vengeance and Triumph. War, Feelings and Remembrance in the Modern Age. Munich 2014, p. 236.

- ↑ Thomas Stolz, Ingo H. Warnke, Daniel Schmidt-Brücken: Language and Colonialism: An Interdisciplinary Introduction to Language and Communication in Colonial Contexts. Berlin / Boston 2016.

- ^ Martin Kaule : North Sea Coast 1933–1945, with Hamburg and Bremen. The historical travel guide. Berlin 2011, pp. 39–41.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schieder: Myth Mussolini. Germans in audience with the Duce. Munich 2013, pp. 18, 142.

- ^ Stefan Goebel, The Great War and Medieval Memory. War, Remembrance and Medievalism in Britain and Germany, 1914–1940, Cambridge 2009, p. 106.

- ↑ Jakob Hort: Bismarckdenkmäler # Bismarckdenkmäler - the four types and their interpretation. In: Historical Lexicon of Bavaria . July 17, 2006, accessed May 11, 2019 .

- ^ Wilhelm Füßl : [ The beggar monk and his friends. ] In: Culture & Technology. 4/2015, ISSN 0344-5690 , p. 52.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): Politics in Bavaria 1919–1933. Reports from the Württemberg ambassador Carl Moser von Filseck. Munich 1971, p. 250.

- ↑ Hubert Winkels: Rainald Goetz meets Wilhelm Raabe. The Wilhelm Raabe Literature Prize, its history and topicality. Göttingen, 2001.

- ↑ Dates and first names according to the information on the estate www.braunschweig.de

- ^ Helga Mitterbauer: Nazi literary prizes for Austrian authors. Böhlau Verlag Wien, 1994, ISBN 978-3-205-98204-3 , p. 101 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ^ A b Hubert Winkels : Rainald Goetz meets Wilhelm Raabe: the Wilhelm Raabe Literature Prize, its history and topicality. Wallstein Verlag, 2001, p. 24 f. ( online ).

- ↑ Horst Denkler: Crisis of the Raabe Society. Balance sheet and perspectives. Lecture at the annual meeting of the Raabe Society on September 23, 1994 in the Lower Saxony State Library in Hanover. In: Yearbook of the Raabe Society. Volume 36 (1995), ISSN 0075-2371 , pp. 14-26 ( degruyter.com ).

- ↑ Joachim Kermann, Hans-Jürgen Krüger (Ed.): 1923-24, separatism in the Rhineland-Palatinate region. An exhibition by the Rhineland-Palatinate State Archives Administration at Hambach Castle. Landeshauptarchiv, Koblenz 1989, ISBN 3-922018-67-X , p. 256.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schieder: Myth Mussolini. Germans in audience with the Duce. Munich 2013, p. 18, p. 142.

- ^ Information committee of the Ev.-Luth. Church in Namibia (ed.), Afrikanischer Heimatkalender, Windhoek 1998, p. 108.

- ^ Fritz Behn, Bei Mussolini - Eine Bildnisstudie, Stuttgart 1934, p. 74.

- ↑ Thomas Garke-Rothbart: "... vital for our business ...": Georg von Holtzbrinck as a publishing company in the Third Reich. Walter de Gruyter, 2008, ISBN 978-3-598-44124-0 , p. 88 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ See today's description by the Evangelical Lutheran Church District Lübeck-Lauenburg: Art in the Luther Church. ( Memento from June 1, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) In: kk-ll.de, accessed on April 12, 2019 - Section: The Luther relief by Fritz Behn (1878–1970) .

- ↑ For the history of the community, see the Evangelical Lutheran Church District Lübeck-Lauenburg: History of the Lutheran Church Community of Luther-Melanchthon. ( Memento from June 1, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) In: kk-ll.de, accessed on April 12, 2019 - Section: Part II - The Luther Congregation is being built up .

- ↑ Susanne Panholzer-Hehenberger: The image of man in sculpture in Austria between 1938 and 1945. Vienna 2008, p. 33 ( PDF; 764 kB ).

- ^ National Socialist Monthly Bulletins. 1938, pp. 544 f., 560 f., 840 f., 968 f. and 1024 f.

- ^ Anonymous: man of action and artist: Fritz Behn. In: National Socialist monthly books. 1938, pp. 1.106-1.111.

- ^ Database of the Central Institute for Art History, German Historical Museum and House of Art with information on all exhibited works of art. Search under the keyword "Fritz Behn".

- ^ Ingrid Adamer : Albert Bechtold 1885–1965. Böhlau, Vienna 2002, pp. 225, 230 f.

- ^ Ingrid Adamer: Albert Bechtold 1885–1965. Böhlau, Vienna 2002, p. 246.

- ^ Ingrid Adamer: Albert Bechtold 1885–1965. Böhlau, Vienna 2002, p. 243.

- ↑ Hartmut Berghoff , Cornelia Rauh-Kühne : Fritz K. A German Life in the 20th Century. DVA, Stuttgart / Munich 2000, ISBN 3-421-05339-1 , p. 338.

- ↑ Alois Knoller: History: Technology was more than a factory community. In: Augsburger Allgemeine . Local (Augsburg). June 4, 2012, Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- ^ Die Stadt Salzburg 1941. Newspaper documentation, compiled on the basis of contemporary daily newspapers by Siegfried Göllner. P. 384 (PDF).

- ↑ Susanne Panholzer – Hehenberger: The image of man in sculpture in Austria between 1938 and 1945. Vienna 2008, p. 41 ( othes.univie.ac.at [PDF; 764 kB; accessed on April 30, 2018]).

- ↑ 5184 / AB XX.GP The written parliamentary questions No. 4024 - 4263 / J - NR / 1998 concerning works of art in the possession of the Republic of Austria, which the MPs Mag. Terezija Stoisits and Freundinnen addressed to me on March 15, 1998, will be like follows answered.

- ↑ Thomas Vogtherr: Erich Klahn (1901–1978) - a folk artist? Expert opinion on biographical stations. O. O. 2015, p. 24 ( PDF; 720 kB ( Memento from July 26, 2015 in the Internet Archive )).

- ^ Illustrated newspaper Leipzig. No. 5031, November 1943.

- ↑ Walter Gyßling: My life in Germany before and after 1933 and The Anti-Nazi. Handbook in the fight against the NSDAP. Ed. And incorporated. by Leonidas E. Hill. With a foreword from Arnold Paucker . Donat, Bremen 2003, ISBN 3-934836-45-3 , p. 455.

- ^ Ernst Klee : The culture lexicon for the Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-10-039326-5 , p. 36.

- ↑ Austria / Art: Like a garbage disposal . In: Der Spiegel . No. 27 , 1950, pp. 37 f . ( online - July 6, 1950 ).

- ^ Wilhelm Kosch, Lutz Hagestedt a. a. (Ed.): German Literature Lexicon . The 20th Century, Volume 2, Bern / Munich 2000, p. 165.

- ↑ Birgit Borowski, Fabian von Poser: Baedeker Travel Guide Namibia. Ostfildern 2016, p. 291.

- ↑ a b Philipp Zieger: Behn-Kunst goes to Königsfeld ( memento from August 17, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: Südkurier. September 21, 2007.

- ^ Personal details : Henriette Hoffmann-von Schirach . In: Der Spiegel . No. 31 , 1958, pp. 49 ( online - 30 July 1958 ).

- ↑ Hartmut Berghoff , Cornelia Rauh : The Respectable Career of Fritz K. The Making and Remaking of a Provincial Nazi Leader. Oxford / New York 2015, p. 304 f.

- ^ Museum Auberlehaus Trossingen: State gifts to the Federal Republic of Germany 1949–2012. In: museum-auberlehaus.de. Archived from the original on August 20, 2013 ; accessed on April 30, 2018 (supplement hunting farm).

- ↑ Wolfgang Boiler: Brine and Sun. Bad Dürkheim: attractive and yet in deficit. In: The time . May 22, 1981.

- ↑ Details on the auction catalog in the SWB online catalog. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ↑ See Zeller 2016, pp. 138 ff.

- ↑ Markt Murnau a. Staffelsee. Information on the citizens' meeting on November 4th, 2014. (PDF; 858 kB) In: murnau.de, accessed on October 6, 2019.

- ↑ Ohlsdorf cat. No. 320: The genius of death - the Schutte tomb .

- ↑ Ohlsdorf Cat. No. 319: The genius of death - the Schutte tomb .

- ↑ Ohlsdorf cat. No. 372: The genius of death - the Schutte tomb .

- ↑ See catalog no. 302 in the catalog 3rd German Artist Association Exhibition. Weimar 1906. p. 31 ( Scan - Internet Archive [accessed May 29, 2016]).

- ↑ Elli Schulz: The board at the Schillerbrunnen is smeared. In: derwesten.de, May 29, 2016, accessed on May 29, 2016.

- ↑ Max Schmid (ed.): One hundred designs from the competition for the Bismarck National Monument on the Elisenhöhe near Bingerbrück-Bingen. Düsseldorfer Verlagsanstalt, Düsseldorf 1911. (n. Pag.)

- ^ Fritz Behn: Bust of the State Secretary Solf. Alexander von Gleichen-Rußwurm : Fritz Behn. In: Art for everyone: painting, sculpture, graphics, architecture - 27.1911–1912. Digitized version of the Heidelberg University Library (accessed on May 29, 2016).

- ^ Andreas Zoller: The landscape painter Edmund Steppes (1873-1968) and his vision of a "German painting". Dissertation 1999, p. 179 ( opus.hbk-bs.de [PDF; 548 kB]).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Behn, Fritz |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Behn, Max Adolf Friedrich (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German sculptor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 16, 1878 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Klein Grabow |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 26, 1970 |

| Place of death | Munich |