Body (clothing)

The chassis (Carosse, Kaross) is a cover-like fur cape of some tribes in southern Africa . The item of clothing that was once widespread among the original population was usually worn with the hair side towards the body.

A hymn of praise by the Lozi contains the line "... like a needle sews the skins together to make a body, the chief unites many people."

distribution

In southern Africa, despite the partly tropical climate, it can get very cold in winter, especially at night. The mostly simply ceiling-shaped body protected the indigenous residents from the cold. Their use is described for the local tribes of the Khoikhoi , the San , the Xhosa , the Batswana , the Zulu and the Lozi .

use

The fur garment was naturally mainly used in cold weather and was also used as a bed pad and cover. It was worn with the haircut down, it was taken off for everyday work or dancing. If the body was made from several skins, the upper edge was usually turned over so that the head parts of the skins rested on the shoulders as a kind of collar. The body was held together at the front of the neck, when it fell it mostly fell apart, leaving a large part of the front body uncovered. At lower temperatures, however, the wearer wrapped himself in it and covered at least the entire upper body. Some bodies had small allowances about 60 centimeters below the upper corners, about 30 centimeters long and 20 centimeters wide, which could be used as a kind of glove in the cold.

It was said of the Bechuanas in 1834 that the rest of their clothing was mostly sparse, and that their costume could “hardly be called decent”: “... they wore a long and narrow apron made of small cords, which they fastened well below the loin area; her back is covered with a sheepskin . When it is very cold, they put on an ox skin or the skin of some other animal, which clothing is called a car body, so the chest and stomach remain bare ”.

The women of the Khoikhoi, who had outgrown the girlhood, wore longer loincloths, the body was always supplemented by a cap, mostly made of leather. All three items of clothing were prepared in the same way. The ladies perfumed themselves with Buchu, the strongly smelling extract of various plants. The hair and the bodies of the Khoikhois are said to have been powdered so much that when several women were there, “no European could breathe in the huts”. With the Makololo, a tribe that later became part of the Lozi, the women decorated their bodies “with as many decorations as could afford”. A sister of the Great Chief Sebituane wore so much jewelry that it would have been "a burden for an ordinary man". The bodies of the Bamangwato women were also richly decorated with simple ornaments made from glass beads and straps.

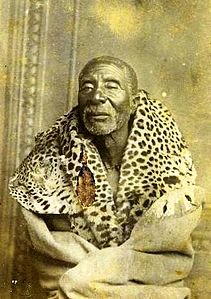

Wild fur animals sometimes provided material for the bodies of higher-ranking tribesmen, especially lions and leopards, which were then only knocked down on ceremonial occasions. The heads of the Matelhapee ( Northern Cape Province , Republic of South Africa) all wore a body, either made of tanned cowhide or of leopard skin or wild cat skin , depending on their rank or wealth.

Emil Holub (1847–1902), who also collected car bodies among other ethnographic objects, reported on the healing of the sick among the Bechuanas: “A remedy that is often prescribed are sweat-inducing vegetables, such as cupping around the locale, around the inside, throughout the body to remove the pain (typhus, dysentery, etc.) spread over larger parts of the same, while the patient will behave to wrap himself in his best coach or in a blanket he has bought, and after the remedy has done its job, the doctor appears to take care of the coach or "to bury" the blanket with the sweat, the perspired disease substances, d. H. to take possession of it while the patient is glad to know that the cause of his evil has been removed from the house. The patient would never dare to ask for it back if, even after his recovery, he saw the doctor in his jackal cloak stalking the streets of the village ”. If a Khoikhoi died, his body was wrapped in an old carriage and buried in it.

Gradually, the natives began to adopt the immigrant customs. not only were bows and arrows replaced by rifles, but also the body by woolen blankets. The explorer Karl Johan Andersson visited the tribal chief in Batoana, the capital of Lechoètébè, in the middle of the 19th century. Upon arrival, the boss wore lush mole fur trousers and "a graceful and very beautiful jackal body" over his shoulders, which he immediately exchanged for a vest and jacket.

Body and headgear made of guereza and leopard skin

( Tanzania , 1957)Luo dancers with Guerezafell body (1968)

Manufacturing

With the hair side down, the stripped skins were stretched out on the ground with stakes and dried. The Batswana women prepared the skins, called "screaming", probably after the sound that is made when the skins rub softly. Prepared by the women, the men sewed them into "beautiful bodies". Large cowhides, on the other hand, were in some areas by several men at a kind of softening festival with butter or some other fat, massaged and stretched while they sat around in a circle and sang songs.

The use of small skins instead of the easy-to-make bodies made of cowhide is likely to be largely due to the Europeans, who considered them to be more valuable and more pleasant and therefore paid better for them. The cloaks made from large carnivores were considered the most valuable by the natives themselves. A body that the South African traveler Wood had made by a Bechuana consisted of 36 mongoose skins, although the subspecies is referred to here as a "monkey", "sewn as neatly as if a furrier had made it". One of the heads had five holes, two of which were of considerable size. With great skill, the Xhosa furrier had used round pieces made of a different type of fur , so that when looking at the fur side no one would have suspected that it was a damaged fur. The care taken in matching the colors was remarkable and it certainly took a number of furs to choose the right color. Wood also noted that the fur was wonderfully light and comfortable and nobody would have thought that it would keep you so warm. Although every Xhosa had some knowledge of how to prepare the skins and how to make a body, there were some who far exceeded them in their skills. It was easy to see whether the body had been made by an ordinary Xhosa or by someone commonly known as a “body maker”.

The qualified body maker used a large, earless needle for sewing and a string for thread. He pre-drilled a few holes with the needle along the sewing edge piece by piece, through which he tightened the tendon thread. The seam corresponded roughly to a sewing machine lockstitch and did not come loose if it was cut in one place. He made sure that the hair was not sewn in, the finished seam was rubbed flat so that it looked like sewn from fur. The sorting and arrangement of the skins also corresponded to the demands that a European furrier would have placed on his work. The seams of the bodies, which were not made by the specialists, differed significantly, they were hard, stiff and coarse and executed in an overlock seam . A narrow but very durable band of leather (usually antelope) held the body together. This also edged the upper edge to protect it from tearing.

trade

For the members of the Batswana ( North Cape and Botswana ), the body was the typical item of clothing. They also sold them to the Cape Colony traders who valued them highly. But coaches were also an important source of income for other South African peoples; in Potchefstroom , a town in the historic Transvaal, they were among the most important items of trade.

The Bechuana made bodies and venerated them to the king or sold them to traders living in Moschaneng, that is, exchanged them for goods. From these they were sent back to the south and offered for sale as bed or sofa covers, or as room decorations. For a caracal body of ten skins, known in South Africa as roikat bodies , the native received goods worth 3 pounds sterling. In exchange for this, he received the following items in Moschaneng: 1. Two blankets and a pair of trousers; 2. a skirt, a cotton blanket, six colored towels, or 3. ten pounds of gunpowder. In the case of resale, the dealer asked for £ 4 in cash, in the colony £ 4 to £ 10, or £ 5 in goods. A car made from four leopard skins was paid for with a musket, two sacks of gunpowder, 10 to 15 pounds of lead, a can of primers and a small gift as an encore and was sold in cash in Moschaneng for 9 pounds, in the colony for 10 to 13 pounds. When rifles ceased to be a commodity due to the ban on the import of weapons, the purchase price was a suit, two woolen blankets, a pair of boots and a large women's cloth, or, with the addition of a sheep to the carriage, a plow. The Berlin fur trader Emil Brass mentioned in 1911 that leopard skin bodies were already in demand in the country and were far too high in price to be considered for export. A car body of silver Schakal skins ( Canis mesomelas ), usually made of 14 skins had in Moschaneng a value of 4 to 10 pounds, one from 30 clip sealskin 3 to 10 pounds, a vehicle body from the skins of ordinary bluish-gray wildcat 3 to 10 pounds , one made of 16 aardwolf skins 4 pounds, one made of 6 thari skins ("a southern lynx, called Thari by the natives") 8 pounds, and one made of 32 genette skins valued from 4 to 10 pounds. The most beautiful bodies to look at were the silver jackal blankets, the most beautiful furs were provided by the Batlapine lands and the part of the region south of the Molapo inhabited by the barolongs.

Types of fur

(1898, South African Museum )

As expected, the bodies were mainly made of skins from the fur animals found in the area. For daily use, skins that were as large as possible and required little sewing work were preferred, above all cowhides. The Bakalahari are traditionally referred to as the oldest of the Batswana tribes; they are said to have owned huge herds of large horned cattle before they were driven into the desert. The Batswana, for example, are still important cattle breeders today. The bodies of the Khoikhoi were also mostly made of cowhide. Other fur suppliers kept there as livestock are mainly goats and sheep. Smaller skins are also used for loincloths, preferably antelope skins or goat skins , on which the hair is only left on the extremities. The Khoikhoi used to call the front apron "jackal" because, according to a description from 1877, it usually consisted of a jackal skin . The Dutch settlers also called the two aprons "front body" and "rear body".

The Bakalahari, who in addition to their own needs, operated a considerable trade in self-made car bodies, made them around 1872 from goat skin, antelope skin and the warmest of the skins found there, the fur of the desert fox , the fennec. Not all skins of the hunted animals were made into clothing for personal use, and not all were processed, some were sold unprocessed to traders. In 1911, Brass wrote of the Kamafuchs or Cape foxes that his skins from what was then German South West Africa ( Namibia ) were only rarely sold , but “more often the“ body ”made by the natives from the skins of this fox”. The hides of the golden wolf , the golden jackal and the black-backed jackal also fell , which resulted in a very good-looking, high-quality body. The skins of the black-footed cat and other spotted cats and the caracal follow in value . Caracal skins were made into much sought-after bodies, but since it took too long for a Bechuana to acquire enough skins to make a decent body, only small roikat bodies containing eight to ten skins came on the market.

In addition, the skins of other small fur animals were used, as well as a large number of duiker skins, skins of the 'puruhuru' (Syriac? "Ibex"), as well as lion skins , leopard skins and hyena skins . The Bakwains bought tobacco from the eastern tribes, then bought hides from the Bakalahari, tanned them, and sewed them into bodies. David Livingstone reported that while he was in Bechuanaland , twenty to thirty thousand skins were being made into bodies. With the Batlapines, Holub saw that in the royal hut there were bodies made of fur from the aardwolf , the gray fox, the black- backed jackal, and the black- spotted Genetta . They also made car bodies from Hartebeest skin ( hartebeest ). He wrote of the Bamanaquato, after Holub, a people in the northern part of central South Africa, that they had chosen their little bodies made of Hartebeest fur as their national coat.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Books.google.de, Rhodes-Livingstone Museum: The Occasional Papers of the Rhodes-Livingstone Museum . No. 1-16, in one edition, Manchester University Press, 1974, p. 104.

- ^ Books.google.de, Maud Cuney-Hare: Negro Musicians and their Music . Primary source Rose, Cowper: Four years in Southern Africa . P. 84 (English).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h JG Wood: The Uncivilized Races of Men in All Countries of the World: Being a Comprehensive Account of their Manners and Customs, and of their Physical, Social, Mental, Moral and Religious Characteristics . 1870 (English). Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- ^ Books.google.de: The Abroad. A daily newspaper for customers of the intellectual and moral life of the peoples in Germany , 7th year, JG Cotta'sche Buchhandlung, Munich 1834, p. 712. Last accessed on November 27, 2017

- ↑ a b c d e f g www.gutenberg.org, Emil Holub: Seven Years in South Africa. Experiences, research and hunts on my travels from the diamond fields to the Zambesi (1872–1879) . Volume 1, Vienna 1881. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- ↑ books.google.de, George Thompson: Travels and Adventures in Southern Africa , Volume 1, London 1872, p. 192 (English).

- ^ Charles John Andersson: Lake Ngami, or, Explorations and Discoveries During Four Years' Wanderings in the Wilds of Southwestern Africa . Harper & Brothers, New York 1861, pp. 418-419 (English). Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ^ Books.google.de, Andrew C. Ross: Mission and Empire . P. 42 (English).

- ^ A b Emil Brass : From the realm of fur. Publishing house of the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1911, pp. 406, 463.

- ^ A b www.missionaryetexts.org, David Livingstone: Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. Journeys and Researches in South Africa . (English). Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- ↑ www.beck-shop.de, Christoph Marx: Country stories South Africa, history and the present . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2012, p. 17. ISBN 978-3-17-021146-9 . Last accessed November 27, 2017.