Croatian kuna

| Kuna | |

|---|---|

| Country: |

|

| Subdivision: | 100 lipa |

| ISO 4217 code : | HRK |

| Abbreviation: | kn |

|

Exchange rate : (August 24, 2020) |

1 EUR = 7.533 HRK 1 CHF = 7 HRK |

The kuna ( Croatian for marten ) has been the currency of the Republic of Croatia since May 30, 1994 and is issued by the Croatian National Bank. One kuna is equal to 100 lipa (Croatian for linden tree ). The international currency code is HRK; in Croatia the abbreviation kn is mostly used. The kuna is convertible and is considered a stable currency.

The name comes from the medieval use of marten skins as fur money for trade and the payment of taxes in the Croatian provinces of Slavonia and the coastal region (today Kvarner and Istria ). This fur money was first mentioned in 1018 in the small town of Osor on the island of Cres as a means of payment for the Croatians . Duties and taxes could be paid with the fur money. A small memorial in the shape of a marten reminds of this today.

From this, the Banovac (plural Banovci ; Latinized Denarius Banalis ) developed, a Croatian silver coin of stable value which was minted in Slavonia by the Croatian viceroys ( Banus ) from the middle of the 13th century to the end of the 14th century . As a reference to the fur money, the Banovac showed the marten as a coin image, which developed into an important heraldic symbol of the Croatian countries (still in the coat of arms of Slavonia today ).

Referring to the design of the coin and the name of the Banovac, the currency of the Independent State of Croatia (1941–1945) was called the kuna and the denominational coin was called Banica (1 Kuna = 100 Banica) during the Second World War .

After the independence of the Republic of Croatia in 1991 until the introduction of the kuna in 1994, the Croatian dinar served as a transitional currency during the war in Croatia .

history

The peoples who immigrated or lived in the territory of Croatia left their mark on many segments of life, including coinage. According to the available sources, the Croatians began minting their own coins in the territory of Croatia in the late 12th century. Before that time, they had made replicas of the Byzantine coins . The money of the White Croats , a tribe that lived in East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, is believed to be the oldest Croatian money. The Croatian princes Slavnikovci minted their coins in the 10th century. The connection between the White Croats and the South Slavic Croats has not yet been fully proven.

In 1102 Croatia entered into an alliance with Hungary . In the context of these political relations, the Hungarian ruler was the common king for Croatia and Hungary. However, Croatia had a certain degree of independence, so that its rulers were allowed to mint their own coins, which were valid throughout Croatian territory. A representative example of Croatian money are the Banovci (singular Banovac ), minted by the Croatian viceroy between 1235 and 1384. They were minted from fine silver in the mints in Zagreb . On the coins, valued for their composition and quality, there was an image of a marten. Slavonia still has the marten in its coat of arms (see coat of arms of Slavonia ).

Over a period of more than five centuries (1294–1803), the Dubrovnik Republic minted coins that had great appeal among collectors both in Croatia and abroad. Other Croatian coastal cities, for example Zadar , Šibenik , Trogir , Split and Hvar , also minted their own coins. In the early 14th century, the Croatian princes Pavao and Mladen Šubić also minted their own coins. In the first half of the 16th century Nikola Zrinski the Third minted coins that collectors consider to be the most beautiful Croatian coins. The big groschen and the talir (cf. taler ) are particularly valued .

The first Croatian paper money came from the town of Pag in 1778. Before the introduction, the town of Pag paid its officers, employees and doctors in salt. When paper money was introduced, the salt amount was converted into lira and a receipt was issued for that amount.

The coins and banknotes issued during the reign of Croatian prince Josip Jelačić are also considered to be the original Croatian currency. Josip Jelačić was promoted to Ban in 1848. These were financially unstable times and the change for daily payment transactions was scarce. The Council of the Ban has minted its own coins in Zagreb - the Križar from copper and the Forint from silver . Municipalities, companies and trading houses support the issue of paper banknotes with their own guarantees.

In the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (announced in December 1918), the currency was issued by the National Bank. The units were called dinars and para . An agreement was reached with the National Bank of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia on the question of the independence of the currency (the names Kuna or Banovac were considered), which should come into circulation in parallel with the Yugoslav dinar. But these plans were never realized due to the outbreak of World War II.

The currency in the Independent State of Croatia (1941-1945) was the kuna, which was divided into 100 banica . After the Second World War, Croatia did not have its own currency because it was part of Yugoslavia .

On May 30, 1994, the kuna replaced the transitional currency Croatian dinar , which was introduced on December 23, 1991 after Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia. The exchange rate was 1000 Croatian dinars for 1 kuna. Due to the occupation of large parts of Croatia by Serbian troops, it took another four years until this currency could be used on the entire state territory of Croatia. The Republic of Serbian Krajina (Serbian Republika Srpska Krajina ), which was specifically proclaimed by vendors at the time and was never internationally recognized, used its own currency, the dinar of the Republic of Serbian Krajina (Serbian Dinar Republike Srpske Krajine ).

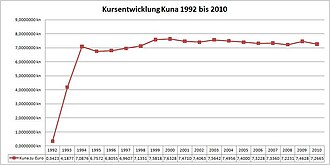

Course development

In contrast to other currencies, the rate of the Croatian kuna is not formed by the international financial market, but is determined by the Croatian National Bank. Since the kuna is very closely related to the euro exchange rate, the currency can be described as extremely stable. National and international currency experts accuse the National Bank of artificially keeping the kuna rate high and thus damaging Croatia's economic and political development. However, it was achieved that the inflation rate could be kept low, in contrast to previous years.

The kuna has been changeable everywhere since 1993 (international convertibility ). The external stability of the currency was favored by the fact that Croatian citizens and companies were used to keeping their money in foreign currency and thus had considerable foreign exchange reserves .

Present and future introduction of the euro

Since Croatia's preparations for membership of the European Union began , important transactions, such as loan agreements, have often been carried out on a euro basis. In addition, one often encounters price offers in the euro currency unit in everyday life. However, due to legal regulations, payments and bills are always in kuna. The applicable daily rate is decisive. At the end of 2014, central bank governor Boris Vujcic considered it impossible to introduce the euro before 2019 due to resistance among the population.

Croatia has been participating in Exchange Rate Mechanism II since July 2020 and could therefore join the monetary union and introduce the euro in early 2023 at the earliest.

Coins and banknotes

Republic of Croatia (since 1994)

Since 1994 there have been coins of 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 and 50 lipa as well as 1, 2 and 5 kuna. They are issued in two versions: once with the name of the plant or animal shown in Croatian in odd years and a second version with the Latin name in even years. The two lowest denomination coins, 1 Lipa and 2 Lipa, are usually not in regular circulation.

All coins are made of different metals and alloys , differ in weight, diameter and thickness of the blanks (blanks), whereby the edge of the coins is smooth on Lipa coins and ground on Kuna coins. On the reverse of all denominations of Lipa and Kuna coins, the semicircular legend Republika Hrvatska can be seen in the upper half and the national coat of arms is in the middle.

| value | Illustration | Design on the front | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Croatian | Latin | German translation | ||

|

1 lipa jedna lipa |

|

kukuruz | Zea mays | Corn |

|

2 Lipe dvije lipe |

|

vinova loza | Vitis vinifera | grapevine |

|

5 Lipa pet lipa |

|

hrast lužnjak | Quercus robur | English oak (branch) |

|

10 Lipa deset lipa |

|

duhan | Nicotiana tabacum | Virginian tobacco |

|

20 Lipa dvadeset lipa |

|

maslina | Olea europaea | Olive tree (branch) |

|

50 Lipa pedeset lipa |

|

velebitska degenija | Degenia velebitica | Velebit-Degenia |

|

1 kuna jedna kuna |

|

slavuj | Luscinia megarhynchos | nightingale |

|

2 Kune dvije kune |

|

tunj | Thunnus thynnus | Bluefin tuna |

|

5 kuna pet kuna |

|

mrki medvjed | Ursus arctos | brown bear |

|

25 Kuna dvadeset i pet kuna |

kuna | Martes martes | marten | |

There are banknotes of 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500 and 1000 kuna; Until 2008 there was also a 5 kuna banknote, which was withdrawn from payment transactions because printing the banknotes was no longer profitable. However, they can still be exchanged in branches of the Croatian National Bank.

| value | Front design | Design of the back |

|---|---|---|

| 5 kuna (withdrawn) |

Petar Zrinski and Fran Krsto Frankopan |

Varaždin Castle |

| 10 kuna | Juraj Dobrila | Amphitheater of Pula and Motovun |

| 20 kuna | Josip Jelačić | Castle of the Counts of Eltz in Vukovar |

| 50 kuna | Ivan Gundulić | Top view of the castle walls and the old town of Dubrovnik |

| 100 kuna | Ivan Mažuranić | Church of St. Vitus (Sv. Vid) in Rijeka |

| 200 kuna | Stjepan Radić | former command building Osijek |

| 500 kuna | Marko Marulić | Diocletian's Palace , Split |

| 1000 kuna | Ante Starčević | Equestrian statue of King Tomislav , Zagreb Cathedral |

The Croatian banknotes are produced in Germany and Austria by the companies Giesecke & Devrient and OeBS . Their layout is similar to the DM notes from the last series.

The banknotes are printed on multicolored paper made from 100% cotton fibers. It is very resistant to moisture, non- fluorescent and resistant to bacteria and fungi. The paper of the banknotes contains invisible fluorescent threads that glow blue, yellow and purple under ultraviolet light.

Each denomination of the Kuna banknotes has a characteristically positioned watermark that is colorless built into it. This watermark is identical to the portrait on the face of the banknote.

A metal security strip built into the paper can be seen in a number of small windows on the surface of the face of the banknote. Under ultraviolet light, the fluorescence on the metal security strip becomes visible.

The numerical value of the banknote is printed in the negative on the metal security strip in a continuous series. So you can alternately see the portrait or the central part of the banknote. The letters HK are printed next to the numerical value. This is both the symbol of the country and the name of the currency unit.

All Kuna banknotes are printed on both sides with simultaneous lithography and on the front with intaglio printing, which has an iridescent effect. On the front and back of all denominations, two colors fluoresce under ultraviolet light.

All Kuna banknotes are printed in the central part on the front with a square with the coat of arms of the Republic of Croatia. Next to the right corner, the national anthem, Lijepa naša (Our beautiful country), by Antun Mihanović , is shown in 16 lines in microtogravure. A square is printed as a negative on each banknote. This square is divided into a smaller one, along each side the face value of the banknote is printed in digits and the name of the currency. Triangular elements are shown within the smaller square. By holding the banknote in the light, corresponding elements are added to the back so that the letter H can be seen as a note. At this point the paper is a little thinner and therefore more transparent.

A rectangle is printed on the right side of the portrait, which is placed along the colorful border of the banknote. Inside the rectangle, if you change the angle of view, the hidden legend Kuna becomes visible in gravure. To make the hidden legend visible, it is necessary to hold the banknote flat and at eye level against the light. When the note is moved slightly, the legend becomes visible.

The serial number is printed twice on each banknote, in the upper left corner and in the lower right corner of the front. It is printed in black and contains letters to name the series before and after the seven digits. The numbering glows green under ultraviolet light. In the lower left corner, on the white surface of the banknote, a sign containing certain micro-text is printed for the blind (not with the 5-kuna banknote). On the back of the banknote, in the upper right corner, there are two lines of text: the date of issue of the banknote and a facsimile signature of the governor of the HNB.

Independent State of Croatia (1941–1945)

The kuna coins of the Independent State of Croatia were minted but never put into circulation.

The banknotes were in general use.

| value | Illustration of the front and back |

|---|---|

| 50 Banica (1942) |

|

| 1 kuna | |

| 2 kune | |

| 10 kuna | |

| 20 kuna | |

| 50 kuna | |

| 100 kuna | |

| 500 kuna | |

| 1000 kuna (1941) |

|

| 1000 kuna (1943) |

|

| 5000 kuna (1943) |

|

| 5000 kuna (1943) |

literature

- Editor: Kuna . In: Konrad Clewing, Holm Sundhaussen (Ed.): Lexicon for the history of Southeast Europe . Böhlau, Vienna et al. 2016, ISBN 978-3-205-78667-2 , p. 555 .

- St. Granić: From fur money to modern currency: the kuna . In: Review of Croatian History . No. 4 , 2008, p. 87-109 .

- Aleksandar Benažić: Podrijetlo simbolika kuna na hrvatskom novcu [The origins of the marten symbol on Croatian money] . In: Hrvatsko Numizmatičko Društvo (ed.): Numizmatičke vijesti . Volume 43. No. 1 (54) . Zagreb 2001, p. 74-109 (Croatian).

- Dalibor Brozović: The kuna and the lipa: the currency of the Republic of Croatia . Ed .: Narodna banka Hrvatske. National Bank of Croatia, Zagreb 1994 (English).

- Irislav Dolenec: Hrvatska Numismatika: od početaka do danas . Ed .: Prvi hrvatski bankovni muzej Privredne banke Zagreb. Zagreb 1993.

Web links

- Catalog of modern Croatian coins

- Illustration of Croatian dinars and kuna banknotes

- Illustrations of the banknotes

- Illustrations of the coins

- The banknotes of Croatia

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jesus Crespo-Cuaresma, Jarko Fidrmuc, Maria Antoinette Silgoner: "On the Road: The Path of Bulgaria, Croatia and Romania to the EU and the Euro", p. 848

- ^ Croatian currency kroatien-lexikon.de accessed on: May 7, 2010

- ^ Vojmir Franicevic and Evan Kraft: "Croatia's Economy after Stabilization", p. 671

- ↑ Monetary union is getting bigger: Euro family is growing: The next candidates after Lithuania - economic news. In: focus.de. December 15, 2014, accessed July 3, 2015 .

- ↑ Croatia wants to participate in Exchange Rate Mechanism II from 2020 , accessed on July 3, 2019

- ↑ Features of Kuna Banknotes ( Memento from December 5, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) hnb.hr accessed on: May 7, 2010

- ^ First Money - History of the Croatian Currency hnb.hr.Retrieved on May 7, 2010