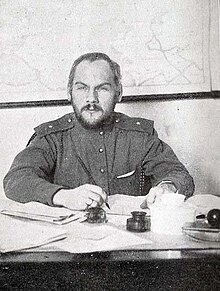

Nikolai Vasilyevich Krylenko

Nikolai Krylenko ( Russian Николай Васильевич Крыленко , scientific. Transliteration Nikolaj Vasil'evič Krylenko ; born May 2, jul. / 14. May 1885 greg. In Bechtejewo , Smolensk ; † 29. July 1938 in Moscow ) was a Bolshevik revolutionary , Politician and later lawyer in Russia . He had a major impact on the development of the Soviet judicial system until the mid-1930s.

background

Krylenko's father was already a proponent of revolutionary ideas. Krylenko himself came during his studies of literature and history at the University of St. Petersburg of the Social Democratic Party of Russia (RSDLP) in, where he the Bolsheviks drew to. For this he was therefore during the revolution of 1905 a member of the short-lived city Soviet of Saint Petersburg . After the revolution failed, he was arrested by the tsarist authorities in 1907 . Dismissed for lack of evidence without judgment, he moved to what was then the Russian Empire belonging Lublin .

In 1909 he returned to the Russian capital St. Petersburg and continued his studies. He briefly left the RSDRP, but rejoined in 1911. In 1912 he served in the army and when he was discharged in 1913 he held the rank of sub-lieutenant . He worked for the Bolshevik newspaper Svjesda since 1911 and in 1913 made it assistant to the main party organ of the Bolshevik Duma faction, Pravda . His journalistic activity led to his exile in the same year in Kharkiv , Ukraine , where he obtained a degree in law. Afraid of being arrested again, he fled to Austria-Hungary in 1914 and, at the beginning of the war, settled in the Swiss exile of his party comrade Lenin . The party sent him back to Russia in 1914 to help build an underground communist organization. However, his subversive activity was not very successful. He was arrested as a deserter shortly after his arrival in Petrograd and, after a few months in prison, was sent to the Southwest Front with the rank of ensign in the spring of 1916 .

Revolutions 1917

After the February Revolution of 1917 , Krylenko headed the soldiers' council of his regiment , then the division , and was eventually elected to the 11th Army Soviet . Since the Bolsheviks were in opposition to the provisional government under Kerensky after Lenin's return in April 1917 and Krylenko represented their position, he had to give up this post on May 26, 1917 due to resistance from non-Bolshevik groups.

In June 1917 he joined the military organization of the Bolsheviks and was elected to the 1st All-Russian Congress of Soviets. There the Bolshevik faction elected him to the newly created permanent “ All-Russian Central Executive Committee ”. He left Petrograd on July 2 to join the military headquarters in Mogilev , but was imprisoned after the failed first Bolshevik coup on July 4, 1917. After General Kornilov's attempt in September 1917 to gain dictatorial powers failed, the Krylenkos party brought a decisive increase in power. He was released again.

In the preparation of the October Revolution he was actively involved in the " military revolutionary committee " MRKP and chairman of the " Congress of the Northern Regions of the Soviets ". On October 16, ten days before the start of the revolution, he told the Bolshevik Central Committee that the garrison of Petrograd would support this.

In the course of the coup, the ensign made a name for himself by taking the Stavka military headquarters in Mogilew and the murder of the then Commander-in-Chief Nikolai Duchonin by the party's Red Guards . He had refused open peace negotiations with the German Reich and was lynched in prison , while Krylenko took over his position on November 9th. Mikhail Bontsch-Brujewitsch became the garrison chief in Mogilew .

Together with Trotsky, Krylenko prevented loyal troops of the Provisional Government led by Kerensky and Pyotr Krasnov from recapturing Petrograd.

Red Army

Several days before Duchonin's murder, on October 25, 1917, he was appointed People's Commissar of the remaining Russian armed forces by the 2nd All-Russian Congress, along with Dybenko and Nikolai Podwoiski . In this capacity he drove the revolutionary upheaval of the structure by approving and promoting the formation of committees, the abolition of military ranks, and the election of officers . However, his position remained that of an estate administrator, because on January 29, 1918 he had to order the complete demobilization of the old army .

After this was done, Krylenko switched to the apparatus under Leon Trotsky , who had been used to form a Red Army . His organizational talent is said to have lagged far behind his rhetorical skills. Here, too, he continued to pursue his idea of an armed force that was led according to " revolutionary " and not according to classic military principles. Enemy troops were to be induced to defeat by propaganda . However, this strategy turned out to be a disaster for the newly formed Russian troops. In February 1918 the German army started Operation Faustschlag . The collapse of the Red Army became evident when the armed forces of the Central Powers captured Minsk and Kiev within a week . This induced Lenin and the Central Committee to conclude the peace negotiations in the peace of Brest-Litovsk .

Leon Trotsky now pursued the further development of the Soviet army on the premises of regular military systems and with the help of officers from the old army of the tsar . On March 4, 1918, he created a Supreme Military Command, headed by the former Chief of Staff of the Tsarist Northern Front, Mikhail Bontsch-Brujewitsch . However, this made Krylenko redundant in the military organization and had to look for another field of activity. On March 13th he was appointed to the People's Commissariat for Justice.

Soviet judicial apparatus

From 1918 to 1922 he acted as chairman of the nationwide revolutionary tribunals of the “ All-Russian Central Executive Committee ” and was also a member of the public prosecutor's office. On June 23, 1918, in connection with the verdict against Captain Alexei Shchastny , he declared that he was not sentenced to “death” but “to shooting ”, which did not stand in the way of the abolition of the death penalty . In 1919 he formally abolished the possibility of the Cheka executing people without judgment.

After 1922 he was appointed Deputy People's Commissar for Justice of the RSFSR . From 1931 he headed this commissariat and became attorney general. He served as the lead prosecutor in various show trials in the 1920s - such as the Shakhty trial - and 1930s in the Soviet Union. From 1927 to 1934 he was a member of the Central Control Commission of the KPR (B) .

In general, it can be summarized that a large part of the early development of the Soviet judicial system and Soviet criminal law was significantly influenced by Krylenko. Thus he is an important reference person when looking at Soviet history (not just in relation to the judiciary) up to the thirties. Krylenko is also very important as a source of the trials in which he participated as the main prosecutor, as he had the corresponding minutes published in his position as People's Commissar for Justice. This is especially true of the trials from the period of the Russian Civil War and the early twenties, for which his publications are practically the only reference. His role is discussed in great detail by Alexander Solzhenitsyn .

Sports official

In chess , Krylenko was a player in the 1st category, which corresponds to an Elo rating of 2000 by today's standards. As a high state official he promoted the development of the Soviet chess school , giving the game a political dimension: Soviet chess should prove to be superior to the “bourgeois” European chess masters. To this end, he popularized chess as a mass sport; a tournament with 1,300 participants took place in Leningrad in 1926. Krylenko also made sure that tournaments were held outside the traditional chess strongholds of Moscow and Leningrad and that talent was promoted. He acted as editor of the popular chess magazine 64, which appeared from August 1924, and was instrumental in the organization of the chess tournaments "Moscow 1925", for which he provided a budget of 30,000 rubles , "Moscow 1935" and "Moscow 1936". Almost all world-class players of the time, with the exception of Alexander Alekhine , who was considered undesirable in the Soviet Union , were invited to these tournaments . Krylenko particularly sponsored the young Mikhail Botvinnik , for whom he organized a competition against Salo Flohr as early as 1933 . Botvinnik himself reports in his autobiography that Krylenko tried (albeit in vain) in 1935 to manipulate a game result in Botvinnik's favor. After Krylenko's execution , his name could not be mentioned for years. It was only during the thaw , in the course of his rehabilitation, that his services to the Soviet chess game were recognized again.

Krylenko was an avid mountaineer who made several expeditions to the Pamir Mountains . In 1935 he was awarded the title of Master of Sports for this.

Theoretician of the Soviet judicial system

In the 1920s and 30s, in his role in the Soviet judicial system at the time, Krylenko wrote a number of books and articles in which he theorized that under socialist law political and non-criminal considerations would play a decisive role in judging guilt, innocence or punishment . He theorized that the confession provides the ultimate proof of the guilt of the accused and that the exact definition of criminal acts and a correspondingly precise judgment (so-called system of "dosing") are unnecessary in socialism. He introduced these views in two bills, 1930 and 1934.

Furthermore, he went into the work From the penal institution to the reformatory and educational institution about the character and transformation of the Soviet penal institutions into reformatory institutions, which, in contrast to capitalist prisons, would lead to a cleansing of the prisoners into happy working people. This book is examined in great detail by Alexander Solzhenitsyn in his work The Archipelago GULAG , albeit not from a neutral point of view, with regard to the discrepancy between theory and practical implementation. It should be noted that in addition to his legal work, Krylenko also had a great influence on the character of the Soviet judicial system in the form of his writings.

Despite his quite influential position, his conclusions and theories have not been accepted without criticism. Some Soviet lawyers, like Andrei Vyshinsky , contradicted Krylenko's statements. It has been argued that Krylenko's imprecise definitions of crime and his refusal to define punishment more precisely, created arbitrariness and instability within the penal system, thus countering the interests of the Soviet state. The debate lasted until 1935 and was not ended.

Victims of the Stalin Purges

After the assassination attempt on Kirov on December 1, 1934 and the beginning of the Great Terror , Krylenko gradually lost his influence on the Soviet judiciary to Vyshinsky. He was already a prosecutor in the first two Moscow trials against old Bolsheviks in August 1936 and January 1937. Krylenko's confidante, the Marxist theorist Yevgeny Paschukanis , was suspected of criticism at the end of 1936, arrested in January 1937 and shot in November of the same year. Shortly after his arrest, Krylenko had to practice “self-criticism” and publicly declare that Vyshinsky and his other critics were right.

Since he held the post of People's Commissar for Justice for the entire Soviet Union from July 20, 1936, Krylenko was not yet affected by the first phase of the Great Terror. At the beginning of 1938 this changed suddenly. In the first meeting of the reorganized Presidium of the Supreme Soviet in January 1938, the Presidium member Mir Jafar Abbasovich Bagirov attacked him publicly:

“Comrade Krylenko is only concerned with the affairs of his commissariat. But running the Justice Department takes great initiative and a serious, disciplined attitude. Meanwhile, Comrade Krylenko spent much of the time climbing and traveling, and now playing chess. […]

We should know what we are dealing with in the case of Comrade Krylenko - the Minister of Justice? or a climber? I don't know what Comrade Krylenko himself thinks about it, but he is without a doubt a poor people's commissar. I am sure that Comrade Molotov will take this into account when proposing candidates for the new Council of People's Commissars of the Supreme Soviet. "

Just two days later, Krylenko was replaced by Nikolai Rytschkow and arrested 12 days later by the NKVD . After three days in NKVD detention and the associated torture, he “confessed” to being an “underminer” under Article 58 of the Soviet Criminal Code since 1930 . On April 3, he expanded his confession and now declared that he had been an enemy of Lenin even before the revolution . When he was last questioned on June 28, 1938, he confessed to having recruited thirty employees for his anti-Soviet organization in the Justice Department.

Krylenko was by a Military Collegium of the Supreme Court on 29 July 1938 sentenced to death . The trial lasted 20 minutes - enough time for Krylenko to revoke his forced confessions. He was found guilty and was to be shot immediately . Krylenko was rehabilitated by the Soviet government in the course of de-Stalinization in 1955.

Krylenko's wife, the old Bolshevik Elena Rosmirowitsch , survived the purges through inconspicuous behavior as an employee of the party archives. His sister Elena married the US author Max Eastman and emigrated with him to the USA .

Quotes

“We don't even want to talk about individual personal losses […] In our time, when struggle is the main content of our lives, we have somehow got used not to consider such irretrievable losses […] The Supreme Revolutionary Tribunal has a weighty word speak [...] The judicial retribution must be carried out with the utmost severity! [...] We didn't come here for fun! "

“The Russian intelligentsia, which faced the acid test of the revolution with the slogans of popular power, emerged as an ally of the black generals and as a mercenary and docile agent of European imperialism. The intelligence has sullied and betrayed its own flags. "

"The verdict cannot be anything other than death by shooting for everyone without exception!"

literature

- Evan Mawdsley : The Russian Civil War ; Birlinn Ltd., Edinburgh, 2005; ISBN 1843410249

- Alexander Solzhenitsyn : The GULAG Archipelago , Scherz Verlag, Bern 1974

- Arthur Ransome : Russia in 1919 ; Kessinger Publishing, 2004, ISBN 1419167170

- Hiroshi Oda: Criminal Law Reform in the Soviet Union under Stalin ; in: Ferdinand Joseph Maria Feldbrugg (Ed.): The Distinctiveness of Soviet Law ; Dordrecht, The Netherlands, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1987, ISBN 9024735769

- Donald D. Barry, Yuri Feofanov: Politics and Justice in Russia: Major Trials of the Post-Stalin Era ; New York, ME Sharpe, 1996, ISBN 156324344X

- DJ Richards: Soviet chess ; Clarendon Press, Oxford 1965

- Andrew Soltis: Soviet chess 1917-1991 ; McFarland & Company, Jefferson 2000, ISBN 0786406763

Web links

- Literature by and about Nikolai Wassiljewitsch Krylenko in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Nikolai Wassiljewitsch Krylenko in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Biography in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia (Russian)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Solzhenitsyn, Gulag Archipelago Part 1

- ↑ Arthur Ransome. Russia in 1919 , Kessinger Publishing, 2004, ISBN 1-4191-6717-0 , p. 46

- ↑ Крыленко, Николай Васильевич: За пиађь лет (1918–1922) . transl .: NW Krylenko; In five years 1918–1922 . Speeches of indictment at the most important trials of the Moscow and Supreme Revolutionary Tribunals; Moscow / Petrograd 1923

- ^ DJ Richards: Soviet chess , Clarendon Press, Oxford 1965; Andrew Soltis: Soviet chess 1917-1991 , McFarland, Jefferson 2000.

- ↑ Hiroshi Oda: Criminal Law Reform in the Soviet Union under Stalin. In: The Distinctiveness of Soviet Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Dordrecht, 1987, ISBN 90-247-3576-9 , pp. 90-92

- ^ Roy Medvedev : New Pages from the Political Biography of Stalin. Published in: Robert C. Tucker (Ed.): Stalinism: Essays in Historical Interpretation. WW Norton & Co, 1977. New edition: Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick (New Jersey), 1999, ISBN 0-7658-0483-2 , p. 217.

- ↑ Donald D. Barry, Yuri Feofanov: Politics and Justice in Russia: Major Trials of the Post-Stalin Era. ME Sharpe, New York, 1996, ISBN 1-56324-344-X , p. 233.

- ↑ Barbara Evans Clements. Bolshevik Women. Cambridge University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-521-59920-2 , p. 287.

- ^ Richard Kennedy: Dreams in the Mirror: A Biography of EE Cummings . WW Norton & Co., New York, 2nd edition, 1980, ISBN 0-87140-155-X , p. 382.

- ↑ northwest Krylenko: Za Pjat 'let ; Moscow / Petrograd 1923, p. 458

- ↑ northwest Krylenko: Za Pjat 'let ; Moscow / Petrograd 1923, p. 48

- ↑ northwest Krylenko: Za Pjat 'let ; Moscow / Petrograd 1923, p. 326

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Krylenko, Nikolai Wassiljewitsch |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Крыленко, Николай Васильевич (Russian); Krylenko, Nikolaj Vasil'evič (scientific transliteration) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian-Soviet revolutionary and politician (Bolsheviks) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 14, 1885 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Bechtejewo |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 29, 1938 |

| Place of death | Moscow |