Sea battle off Chesapeake Bay

| date | September 5, 1781 |

|---|---|

| place | Chesapeake Bay on the Virginia coast |

| output | French victory |

| consequences | Yorktown surrender |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 24 ships of the line, some frigates, 1,794 cannons, 13,000 men | 19 or 20 ships of the line, 6 frigates, 1,670 cannons, 12,000 men |

| losses | |

|

38 dead, |

90 dead, |

The naval battle of the Chesapeake Bay (also called the Battle of the Virginia Capes ) took place on September 5, 1781 between a British and a French navy during the American Revolutionary War . The battle itself was insignificant, but the consequences were of great importance. After the British lost control of the bay, they were forced to surrender at Yorktown , which ultimately ended the American War of Independence.

prehistory

In early 1781, both British forces and separatists were concentrated in Virginia. The British troops were initially led by the defector Benedict Arnold . This was replaced by General William Phillips and at the end of May by General Charles Cornwallis . In June Cornwallis went to Williamsburg , where he received a series of confusing orders from General Henry Clinton to set up a seaport to secure supplies. Cornwallis chose Yorktown as the location of the port. He moved his troops there at the end of July and began to fortify the place. Control of the Chesapeake Bay therefore became the main military objective on both sides.

On May 21st, George Washington , the commander of the Continental Army , and the Comte de Rochambeau , commander of the French Expédition Particulière , met to discuss how to proceed. The Allies considered either an attack on the main British base in New York City or against British forces in Virginia. For either option, the Americans needed the support of the French Navy. For this reason a ship was sent to Cap-Français in Haiti to meet the French Admiral de Grasse , who had been sent from France to the West Indies with a strong French fleet, and to ask him for his assistance. In addition, the allies expected an assessment of the admiral, which military goal he considered possible, with Rochambeau informing him in a personal note of his preference for the operation against Virginia. In the meantime, George Washington and Rochambeau moved their armies to White Plains to await further developments from there.

Arrival of the fleets

Admiral de Grasse reached Cap-Français on August 15 and immediately dispatched the Concorde to Newport to inform George Washington that he would sail to the Chesapeake Bay to support the operation of the allied armies there. Before he left Cap-Français with 26 ships of the line and five frigates, he took 3,200 foot troops on board. He didn't take the usual route to hide his real goal. The British Admiral George Rodney , who had followed de Grasse's course between the West Indies , was however informed of the departure of the French fleet. He believed that part of the fleet would return to Europe, so he commissioned Admiral Sir Samuel Hood with a fleet of only 14 ships of the line to track down de Grasse. Rodney, who was sick, sailed the rest of the fleet to England to recover, maintain the ships, and avoid the Atlantic hurricane season.

On August 25, Admiral Hood reached Chesapeake Bay. However, since he found no French ships, he returned to New York. Meanwhile, his colleague Admiral Thomas Graves had spent several weeks in vain tracking down a convoy organized by John Laurens to bring supplies from France to Boston. By the time Hood reached New York, Graves had already returned. This only had five usable ships of the line.

On August 27, the French admiral Comte de Barras, informed of de Grasse's planned arrival date , left the port of Newport with eight ships of the line, four frigates and 18 transports loaded with weapons and siege equipment. He chose a route that should avoid encountering British ships as much as possible. Meanwhile, Washington and Rochambeau had crossed the Hudson River on August 24th . As a ruse they had left some troops behind. They should hold off any reinforcements on their way to Cornwallis as long as possible.

On August 30th de Grasse reached the Chesapeake Bay and landed the troops to support the blockade of Cornwallis. Two British frigates patrolling the coast were caught by de Grasse in the bay and were unable to inform Graves of the real strength of the French fleet. The news of de Barra's departure led the British to conclude that the Chesapeake Bay should be their destination. On August 31, Graves and Hood combined their fleets and sailed south with 19 ships of the line. Progress was slow as, contrary to Hood's claims, some of his ships were in poor condition and needed repair en route. Graves ships were also affected, so HMS Europa had problems with the rudder. The British fleet finally arrived at Chesapeake Bay on September 5th.

Lineup

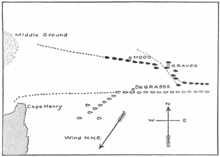

At around 9:30 am, patrol frigates from both parties discovered the enemy ships and both sides initially underestimated the size of the fleets. Both the British and French scouts believed they had Admiral de Barras' fleet in front of them. When Graves realized the real size of the French fleet, he believed he was facing the combined fleets of de Grasse and de Barras. He steered his line towards the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay.

The French ships of the line Glorieux and Vaillant and 4 of the frigates were assigned to control the mouths of the York River and the James River . Many of the anchored ships were missing officers and crew members; a total of about 90 officers and 1,800 sailors. De Grasse realized his bad position to form a ship line against the incoming tide and the given wind and land conditions. At 11:30 am, 24 ships had lifted anchor and sailed out of the bay. On some ships up to 200 men were missing, so that some could not occupy all cannons. De Grasse gave the order to form the line when leaving the bay regardless of the usual order. Since Commodore Louis Antoine de Bougainville was one of the first to leave the bay, he took command of the top management.

At about 1:00 a.m., the two fleets faced each other, but were on different courses. At about 2:00 gave Graves to the sandbar to circumvent "Middle Ground" and form a line parallel to the French ships, the command to a neck . Through this maneuver, the order of the ships reversed and the most offensive squadron of Admiral Hood was moved to the end of the line. The two lines of the ship were in such a way that the front part was within firing range and the rear part was too far away. The British line ran north of the French. As the wind was blowing from the north-northeast and the ships sailed out of the bay to the east, the ships heeled to the south. As a result, the British ships had to keep the lower gun ports closed to prevent water from entering. Only the upper battery decks could be used, while the opposing ships had all decks available. The French fleet was also outnumbered and in better condition, and had the heavier guns on board. In addition, the British ships HMS Ajax and HMS Terrible were in very poor condition at the top. At around 3:45 a.m. there was a larger gap between the French leadership and the rest of the line, which could have easily been severed by the British. However, Graves failed to take advantage of this.

To direct the British end of the line closer to the enemy, Graves gave contradicting signals, which Hood misunderstood. None of the existing options for navigating closer to the enemy made sense to the commander of the end of the line. Any course directed at the enemy limits one's firepower to the bow cannons and subjects the ship to stern fire and enfilade . Graves hoisted two signal flags: first, "line ahead" which means that you should catch up with the ship in front and then take a course parallel to the enemy; secondly, “close action”, which means that you take a direct course towards your opponent and then turn around at an appropriate distance. Hood understood the signals to mean that he should keep the battle line and so slowly get closer to the enemy. As a result, the end of the line was practically not included in the battle.

course

Around 4:00 a.m., about six hours after the first sighting, the British, who had the wind advantage , opened the battle. The HMS Intrepid was the first to open fire on the Marseillais . Very quickly the top and middle of the two lines were drawn into the battle. The French practiced their usual tactics, aiming mainly at the ship's masts and rigging to render the enemy unable to maneuver. So the first two ships, HMS Shrewsbury and HMS Intrepid, were practically impossible to maneuver and fell out of line. The other ships of Admiral Drake's squadron also suffered severe damage, but not as much as the first two. The angle of attack of the British line also played a role. The ships at the top were exposed to stern fire, while they could only fire the few bow cannons at the enemy.

The French also suffered losses. Captain de Boades on the Réfléchi was killed during the bombardment by Admiral Drake's flagship. Four ships in the French tip were shot at by seven or eight ships at close range. The Diadème , which only had four 36-pounders and nine 18-pounders ready for action, was badly hit and could only be saved by the rapid intervention of the Saint-Esprit . When HMS Princessa and the French Auguste came very close, took Louis Antoine de Bougainville a duck approximation attempt , but Drake's team managed to drive the two ships apart. However, this gave the Auguste the opportunity to put the HMS Terrible under fire. Her foremast , which was in bad shape before the battle, was hit by several cannon balls. Their pumps, which were already running at full capacity to keep the ship afloat, were severely damaged by a hit just above the waterline .

At around 5 a.m. the wind turned to the disadvantage of the British. De Grasse gave the signal that the top should sail faster so that the ships behind could intervene in the battle. Bougainville, fighting within range of the muskets , did not want to present the unprotected stern of the ship to the enemy . When he finally sailed ahead, the British interpreted this as a retreat. Instead of following him, they fell back and shot from a long distance. A French officer later said the British attacked from a distance only to later claim that they fought. Sunset finally ended the engagement as both fleets retreated from the bay on a southeast course.

Most of the two fleets were involved in the fight, but the damage on either side was negligible. The back part was as good as uninvolved. Admiral Hood reported that three of his ships had fired a few shots. The repeated confusing signals from Graves and the discrepancies in Hood's record of when which signals were transmitted immediately led to mutual accusations, written statements, and possibly an official investigation.

consequences

De Grasse led his fleet back to the bay on September 8 and blocked it. Admiral Graves broke off the chase of the French fleet on September 10 and returned to New York to have his ships repaired. In doing so, he left control of Chesapeake Bay to the French. The French fleet brought the troops of George Washington and Rochambeau from the northern bay to Williamsburg .

As insignificant as the battle as such was, it had lasting consequences. The British army under General Cornwallis could be completely enclosed on land by the Continental Army and the French and also had no more sea support. Reinforcements could no longer be landed. Likewise, the general's 5,000 soldiers could not be evacuated with the help of the fleet. In contrast, another French fleet could bring supplies and artillery. Without dominating the bay, Cornwallis would have had a chance to escape with his troops and join forces with other troops. After six weeks of containment, Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown. This decided the American War of Independence in favor of the Americans.

Order of battle

Great Britain

| Admiral Sir Thomas Graves' fleet | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ship | rank | Cannons | crew | commander | losses | Remarks | ||

| killed | wounded | All in all | ||||||

| Top management (actually end) | ||||||||

| HMS Shrewsbury | 3rd rank | 74 | 600 | Captain Mark Robinson |

14th

|

52

|

66

|

|

| HMS Intrepid | 3rd rank | 64 | 500 | Captain Anthony James Pye Molloy |

21st

|

35

|

56

|

|

| HMS Alcide | 3rd rank | 74 | 600 | Captain Charles Thompson |

2

|

18th

|

20th

|

|

| HMS Princessa | 3rd rank | 70 | 550 | Rear Admiral Francis Samuel Drake Captain Charles Knatchbull |

6th

|

11

|

17th

|

Flagship of the top management |

| HMS Ajax | 3rd rank | 74 | 600 | Captain Nicholas Charrington |

7th

|

16

|

23

|

|

| HMS Terrible | 3rd rank | 74 | 600 | Captain Hon. William Clement Finch |

4th

|

11

|

15th

|

The ship was badly damaged, which is why it was sunk after the battle. |

| center | ||||||||

| HMS Europe | 3rd rank | 64 | 500 | Captain Smith Child |

9

|

18th

|

27

|

|

| HMS Montague | 3rd rank | 74 | 600 | Captain George Bowen |

8th

|

22nd

|

30th

|

|

| HMS Royal Oak | 3rd rank | 74 | 600 | Captain John Plummer Ardesoif |

4th

|

5

|

9

|

|

| HMS London | 2nd rank | 98 | 800 | Rear Adm. Thomas Graves Capt.David Graves |

4th

|

18th

|

22nd

|

Flagship of the center |

| HMS Bedford | 3rd rank | 74 | 600 | Captain Richard Graves |

8th

|

14th

|

22nd

|

|

| HMS resolution | 3rd rank | 74 | 600 | Captain Lord Robert Manners |

3

|

16

|

19th

|

|

| HMS America | 3rd rank | 64 | 500 | Captain Samuel Thompson |

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

| End (actually top management) | ||||||||

| HMS Centaur | 3rd rank | 74 | 600 | Captain John Nicholson Inglefield |

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

| HMS Monarch | 3rd rank | 74 | 600 | Captain Francis Reynolds |

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

| HMS Barfleur | 2nd rank | 98 | 768 | Rear Admiral Sir Samuel Hood Captain Alexander Hood |

0

|

0

|

0

|

Flagship of the end |

| HMS Invincible | 3rd rank | 74 | 600 | Captain Charles Saxton |

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

| HMS Belliqueux | 3rd rank | 64 | 500 | Captain James Brine |

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

| HMS Alfred | 3rd rank | 74 | 600 | Captain William Bayne |

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

| Assigned frigates | ||||||||

| Top management | ||||||||

| HMS Fortunée | 5th rank | 40 | 300 | Captain Hugh Cloberry Christian |

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

| HMS Sibyl | 6th rank | 28 | 200 | Captain Lord Charles Fitzgerald |

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

| HMS Salamander | Fire | 8th | 45 | Commander Edward Bowater |

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

| center | ||||||||

| HMS Adamant | 4th rank | 50 | 350 | Captain Gideon Johnstone |

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

| HMS nymph | 5th rank | 36 | 240 | Captain John Ford |

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

| HMS Solebay | 6th rank | 28 | 200 | Captain Charles Holmes Everitt |

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

| The End | ||||||||

| HMS Richmond | 5th rank | 32 | 210 | Captain Charles Hudson |

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

| HMS Santa Margaritta | 5th rank | 36 | 255 | Captain Elliot Salter |

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

| Total casualties: 90 killed, 246 wounded | ||||||||

| Source: Isaac Schomberg: Naval Chronology , Volume 4, 1802, p. 377 | ||||||||

France

| Admiral Comte de Grasse's fleet | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ship | rank | Cannons | crew | commander | Remarks | |||

| Top management | ||||||||

| Pluton | 3rd rank | 74 | 700 | Capitaine François Hector d'Albert de Rions | ||||

| Bourgogne | 3rd rank | 74 | 700 | Capitaine Chevalier de Charitte | ||||

| Marseillais | 3rd rank | 74 | 700 | Capitaine Henri-César de Castellane Majastre | ||||

| Diademe | 3rd rank | 74 | 700 | Capitaine Louis-Augustin de Monteclerc | Capitaine de Monteclerc was injured | |||

| Refelchi | 3rd rank | 64 | 600 | Captain Brun de Boades | Capitaine de Boades was killed during the battle | |||

| Auguste | 2nd rank | 80 | 800 |

Commodore Louis Antoine de Bougainville Capitaine de Castellan |

Flagship of the top management | |||

| Saint-Esprit | 2nd rank | 80 | 800 | Capitaine Joseph Bernard de Chabert | Capitaine Chabert was wounded | |||

| Caton | 3rd rank | 64 | 600 | Capitaine Comte de Framond | Capitaine de Framond was injured | |||

| center | ||||||||

| César | 3rd rank | 74 | 700 | Captain Charles Régis de Coriolis d'Espinouse | ||||

| Destin | 3rd rank | 74 | 700 | Capitaine François-Louis du Maitz de Goimpy | ||||

| Ville de Paris | 1st rank | 104 | 1000 |

Lieutenant-général François Joseph Paul de Grasse Major-général Pierre de Vaugiraud Capitaine de Sainte-Césaire |

Flagship of the center | |||

| Victoire | 3rd rank | 74 | 700 | Capitaine François d'Albert de Saint-Hippolyte | ||||

| Scepter | 3rd rank | 74 | 700 | Captain Louis-Philippe de Vaudreuil | ||||

| Northumberland | 3rd rank | 74 | 700 | Capitaine Marquis de Briqueville | ||||

| Palmier | 3rd rank | 74 | 700 | Capitaine Jean-François d'Arros d'Argelos | ||||

| Solitaire | 3rd rank | 64 | 600 | Capitaine Louis-Toussaint Champion de Cicé | ||||

| Citizens | 3rd rank | 74 | 700 | Captain Comte d'Ethy | ||||

| The End | ||||||||

| Scipion | 3rd rank | 74 | 700 | Capitaine Comte de Clavel | ||||

| Magnanime | 3rd rank | 74 | 700 | Capitaine Comte Le Bègue | ||||

| Hercule | 3rd rank | 74 | 700 | Capitaine Viscount de Turpin de Breuil | ||||

| Languedoc | 2nd rank | 80 | 800 | Admiral François-Aymar de Monteil Capitaine Louis Guillaume de Parscau du Plessix |

Flagship of the end | |||

| Zélé | 3rd rank | 74 | 700 | Capitaine Chevalier de Gras-Préville | ||||

| Hector | 3rd rank | 74 | 700 | Captain Renaud d'Alleins | ||||

| Sovereign | 3rd rank | 74 | 700 | Capitaine Chevalier de Glandevès | ||||

| Poor en flûte | ||||||||

| Aigrette | frigate | 26th | 262 | Capitaine Jean-Baptiste Prevost de Sansac de Traversay | ||||

| Total casualties: 38 killed, 184 wounded | ||||||||

| Source: Onésime-Joachim Troude: Bataille navales de la France , ainé Challamel, 1867, Volume 2, pages 103-110 vol.2 | ||||||||

literature

- Michael Lee Lanning: The American Revolution 100. Naperville, 2008, pp. 49-51.

- Barbara Tuchman: The first salute. Frankfurt am Main, 1988, ISBN 3-596-15264-X , pp. 344-348.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Isaac Schomberg: Naval Chronology , Volume 4, 1802, p. 377 (online)

- ^ Yves Joseph de Kerguelen de Trémarec : Relation des combats et des événements de la guerre maritime de 1778 entre la France et l'Angleterre, mêlée de réflexions sur les manœuvres des généraux: précédée d'une adresse aux marins. sur la disposition des vaisseaux pour le combat: et terminée par un précis de la guerre présente, des causes de la destruction de la marine, et des moyens de la rétablir. , Paris 1796, pp. 213-214 ( online )