Yves Joseph de Kerguelen de Trémarec

Yves Joseph de Kerguelen de Trémarec (born February 13, 1734 in Landudal , † March 3, 1797 in Paris ) was a French naval officer , navigator and explorer. He sailed on two expeditions between 1771 and 1774 through the southern Indian Ocean to get to the presumed southern continent of Terra Australis . He discovered a group of islands on February 12, 1772, which he called La France Australe , France of the South . James Cook , who visited the islands in 1776, gave them the name Kerguelen Islands after their first discovery .

family

Kerguelen came from an old, but not very wealthy, noble family in Brittany . His parents were Guillaume-Marie de Kerguelen (1701–1750), an officer in the third infantry regiment, then called the Régiment du Piémont , and commander of a battalion of the Coast Guard Militia, and Constance-Rose Morice de Beaubois (1702–1746). He had a younger sister, Marie-Anne Catherine (1736-1810), who in 1759 married Louis-Charles Poillot de Marolles.

Officer in the French Navy

After finishing school at the Jesuit College of Quimper , he joined the royal French navy in Brest in 1750 as a midshipman , then known as the Gardes de la Marine . This training should prepare him for a career as a future officer. After just four years, and although his rank would not have allowed him to do so, he was involved as an adjutant in the remeasurement of the coast around Brest. The following year he became a member of the Académie de marine, also based in Brest .

After obtaining his officer's license , he served on various ships, including Le Prothe , Le Tigre , L'Algonkin and the frigates L'Héroine and L'Émeraude . At times he also worked as a port officer in the port of Brest in the function of a lieutenant in the artillery. In 1757 he was stationed in a garrison in Dunkirk . There he met his wife Marie-Laurence de Bonte, who came from a Flemish family. Both married in 1758. With her he should have a son, Charles Jean Yves Marie (1767–1843).

From Dunkirk he was deployed on the Sage , a ship with 56 cannons and 450 crew members, and took part with her, as on some of the previous voyages, in the clashes of the Seven Years' War in North America . Kerguelen took command of the ship in early 1761. From March to July of that year he made a trip to the West Indies , where he discovered his interest in hydrography . In 1763 he carried out maritime surveys along the Breton coast. After the previous years had taken him to various areas of the world's oceans, he was now used on land for the next time.

In June 1765, the French navy's bombardment of the pirate town of Larache on the Moroccan coast ended in disaster. The opponents took seven ships and captured 48 French, about 200 were killed. The course of the action, in which several smaller ships sailed up the Oued Loukos and came under fire there, stimulated Kerguelen to design a new type of ship, a gunboat with a shallow draft, which he called the Corvette cannonière . The first of these ships, the Lunette , took part in another war voyage against the Moroccan coast in 1767 under the command of Armand de Kersaint .

Journeys in the North Atlantic 1767–1768

In January 1767 Kerguelen was given command of the Folle , an older frigate equipped with 26 eight-pound cannons and a crew of two hundred. With this he should, at the instruction of the Minister of the Navy Praslin , head for the North Atlantic waters around Iceland , which at that time was still part of Denmark. French fishing boats caught fish that could be processed into stockfish during the summer . Kerguelen should support these fishermen and protect them from attacks, but also ensure that the fishermen comply with the regulations and, if necessary, ensure that the boats themselves are in order. The main problem was that a few years earlier the Danish krone had given a private company a monopoly on fishing off the coast of Iceland. At the same time, this was accompanied by the authorization to have foreign ships that violated this arrested. Three years earlier, they had actually confiscated two French boats and then had them sold and only compensated the owners after diplomatic intervention.

After the ship had been equipped so far, Kerguelen set sail from Brest in mid-April. His course took him past the Mizen Peninsula and the Skelligs in southwest Ireland. On May 11th, the foothills of the Hekla volcano and the Westman Islands came into view. The Folle now followed the Icelandic coast in a westerly direction and met fishermen, primarily of French and Dutch origin, at various points, without anything special having happened. On May 22nd, an approaching storm forced Kerguelen to anchor in Patriksfjord . He stayed there for a few days to explore the area. As a result of a storm on May 29th, 36 French and Dutch fishing vessels, some of them badly damaged, also entered the port. Kerguelen had his crew help repair the boats and at the same time announced that he would be staying in Patriksfjord for some time to provide further assistance if necessary.

Kerguelen was aware of three geographical descriptions of Iceland: those by Isaac de La Peyrère from 1663, Johann Anderson from 1746 and Peder Nielsen Horrebow from 1752. Since he considered these to be incomplete, incorrect and in part contradicting each other, Kerguelen used the time of his stay to in long conversations with Eggert Ólafsson (referred to as Olave in his later travelogue ), who had been living in Patriksfjord for several years and who, in Kerguelen's opinion, was highly learned, to collect further information on Icelandic nature and culture and thus in connection with his own Observations to fill the existing knowledge gaps.

On June 15, the Folle left port and continued her voyage north. His intention was to reach the North Sea along the north coast of Iceland via the island of Grímsey and the Langanes peninsula . He wanted to cross this and head for the Norwegian port of Bergen to take over provisions and have the ship repaired. At Cap Nord, one of the foothills of the Hornstrandir peninsula , which is now known as the Horn , it was over: Kerguelen was faced with an area of pack ice that he did not dare to cross with his ship, which he judged unsuitable. Fishing boats summoned to find a way through the ice could not help either, and so the Folle turned back. He visited Eldey Island , known as the Bird Island , and also picked up a number of bays on Iceland's west coast. Next targets were the Faroe had Islands, the Kerguelen on June 27 in sight. He then steered between the Orkney and Shetland archipelagos , taking up the island of Fair and finally reaching the Norwegian coast. On July 5th, the Folle anchored in the port of Bergen.

Kerguelen stayed in Bergen much longer than planned because he wanted to explore the northern sea routes to the Norwegian city on the way back to Iceland. The southerly wind required for this, however, took us until August 10th. Seven days later he reached Langanes on the north coast of Iceland. Since he only found a few French fishing boats there and there was nothing else for him to do, he began to record and describe this part of the coast and the bays and landing sites there. He also wanted to visit the island of Enchuysen east of Iceland, which was first recorded on Dutch and later on other nautical charts, and actually a phantom island , but of course could not discover it in the specified area.

When the time came at the end of August for the French fishermen to end their fishing season and set off for their home ports, the Folle's mission was also over. On the way home, Kerguelen passed the lonely Rockall rock in the sea , he included this and the nearby Helen's Reef in his report. The Folle arrived in Brest on September 9th .

For the next fishing season, Kerguelen received the same order as the year before. He asked for a more suitable ship for this and received it: the Hirondelle corvette, equipped with 16 six-pound cannons and a 120-man crew . From the first voyage he took over the first two staff officers, Ferron and Duchâtel, and Mr. Soyer de Vaucouleur and Bernard de Marigny were assigned as additional officers. As in the previous year, the drive passed Ireland west, first to the foothills of the Hekla volcano. After another visit to the island of Eldey and a stay of several days in Patriksfjord, where he again provided logistical help to French fishermen, the ship sailed to Bergen for provisions and then to the north coast of Iceland. On the way back to France, Kerguelen chose the route across the North Sea this time. He had measurements taken in the area of the Dogger Bank. After two stays in Ostend and Dunkirk , the Hirondelle reached Brest on September 29th. There were no military incidents this time either.

Kerguelen had used every opportunity available to him on the two trips to have measurements of the sea depth, the current and wind conditions as well as the geographic location, and also targeted places that he assumed were incomplete on the maps available to him or were incorrectly recorded. His work contains several engravings of coastal views as well as detailed maps of individual smaller sea areas, which he had extensively recorded; the measurements he collected led to a significant improvement in the nautical charts of the areas he traveled through. He also wrote down his observations and the results of the conversations he had with various local people, some of them supplemented by explanatory pictures: some in detail, such as his cultural studies on Iceland and Greenland or the people of the Lapps , others as brief ones Reflections such as the formation and movement of icebergs or the cause of the northern lights . Even if these were partly colored by Kerguelen's personal views, and thus did not necessarily meet scientific standards, and were also heavily based on the stories of third parties, they still offer a picture of contemporary conditions and structures and at the same time insights into the views of a scientifically interested French naval officer of the 18th century. For himself they should be the recommendation for two large-scale expeditions to the southern Indian Ocean.

First South Sea expedition 1771–1772

In 1504 Binot Paulmier de Gonneville , after drifting off with his ship at the Cape of Good Hope and losing his bearings, accidentally discovered an inhabited, hospitable area and spent some time there. On the way back he lost the logbooks with his records in a pirate attack. So it was impossible to understand where he had actually been. Since it could not be proven until 1847 that it had landed on the coast of Brazil , there was long suspicion that there might be an as yet undiscovered, habitable southern continent: a Terra Australis .

The loss of a large part of the French colonial empire as a result of the Peace of Paris in 1763 led France to increasingly look for undiscovered areas in order to establish new colonies or at least to establish trade relations. The central area of the Indian Ocean had been navigated by various, mainly Portuguese, ships since the 16th century, and neither Louis Antoine de Bougainville nor James Cook had discovered a corresponding country during their circumnavigation of the world in 1769 and 1771, respectively. In 1739 Bouvet de Lozier (1705–1786) discovered the Bouvet Island , named after him, and suspected that it could be a promontory on this same continent. All this prompted the French crown, at the suggestion of Praslin, to commission Kerguelen with an expedition in March 1771. He was supposed to cross the part of the Indian Ocean lying south of the width of the islands of Amsterdam and Saint Paul in order to find the suspected land and suitable harbors, contact the population and examine the land, especially from the point of view of starting trade with of the local population.

On May 1, 1771, the Berryer set sail under Kerguelen and his deputy Saint Aloüarn (1738–1772) from Lorient . As an astronomer, Alexis-Marie de Rochon (1741-1817) was on board, who later invented the prism named after him .

The first destination was the island of Mauritius , which at the time was still known as Île de France , whose main port, Port Louis , was reached on August 19th. Here Rochon left the group due to professional and personal differences with Kerguelen. The administrator of the island, Pierre Poivre , recommended Rochon to instead join the expedition planned by Marion du Fresnes into the South Seas. Rochon also advised Fresnes on the planning, but was not allowed to take part in the trip by the Governor des Roches, despite the intercession of Poivre and Fresnes. Rochon now undertook various exploratory trips on his own, including to Madagascar. Its failure meant that the position measurements on the further journey were subject to great inaccuracies.

The expedition exchanged the Berryer for a 24-gun flute called Fortune , which remained under Kerguelen's command, and the Gros Ventre , a 16-gun gabarre that Saint Aloüarn took over. Both ships left the Île de France on September 13, but initially pursued another order that Kerguelen had also received. In the spring of that year, the French naval officer Geron de Grenier , who himself knew the area, suggested looking for a more direct route between the Île de France and the port of Pondicherry on the south coast of India, which also belongs to France . The two ships initially headed north and also reached the island of Ceylon . However, unfavorable winds then forced Kerguelen to abandon the company. The only discovery was a sandbar near the island of Coëtivy , which was named Banc de Fortune . On December 8th, the ships returned to Port Louis.

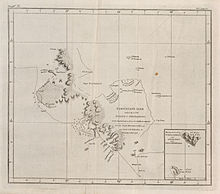

On January 16, 1772 the expedition set out again, this time in a southerly direction. Around February 1st they were able to observe birds that indicated nearby land, but they could not see it themselves. In fact, it was the Prince Edward Islands , which Marion du Fresne had (re) discovered just a few days earlier, on January 13th, but which Kerguelen's ships narrowly missed. On the later published map of the trip, this presumed island was incorrectly entered under the name Nutegat ; the nightingale island in question , on the other hand, is much further west.

On February 12, 1772 Kerguelen's ships reached a small group of rocky islands, which were christened Îles de la Fortune , and the next day a longer coast. Despite the extremely stormy weather, each of the two ships managed to set down a sloop , led by a younger officer , with the aim of getting ashore. Kerguelen then found himself unable to maintain the position with his ship in order to take up his dinghy again.

Because of the bad weather conditions, especially the thick fog, he was unable to re-establish contact with the Gros Ventre in the next few days or to find the place where he had dropped off his boat. Since there were also damage to the mast and he assumed that the Gros Ventre was adequately equipped and that Saint Aloüarn was experienced enough to continue the expedition alone, he finally set a course towards Port Louis, which he reached on March 16. After all, both captains managed to roughly map part of the southwest coast, for example from the Île de l'Ouest to the Gallieni Peninsula , and to name some bays, capes and nearby islands.

Saint Aloüarn was luckier, and so he not only took his own group under Charles Marc du Boisguehenneuc (also spelled Bois Guéhenneuc), which hoisted the French flag at the place of their landing and thus took possession of the country on behalf of France, but also that of Fortune under François Étienne de Rosily-Mesros (1748–1832) on the Gros Ventre .

After the Fortune could no longer be found, he did what had actually been agreed between him and Kerguelen for precisely this case: He sailed to an agreed meeting point at Cape Leeuwin , the southwestern tip of Australia. On March 17, he reached the adjacent Flinders Bay , but could not land there because of the bad weather and also not take a position. He therefore set course north and reached Shark Bay on March 29 , where he allowed himself and his crew, who were suffering from emaciation and scurvy , a few days to relax. On March 30, he let a team under Mengaud de la Hague go ashore and explore the surrounding area. The official ceremony for claiming the land for France took place on the offshore Dirk Hartog Island . There the French flag was hoisted and an official document and two coins were buried in a bottle.

Because Kerguelen did not appear, Saint Aloüarn finally broke off the expedition on April 8 and left Shark Bay. The Gros Ventre returned to Port Louis on September 5th via Timor Island and Batavia, today's Jakarta - which was very surprising for the administration there, as the ship had actually already been abandoned. The crew was in very bad shape, however, because Saint Aloüarn, like many others on board, had contracted a tropical fever en route . Mengaud de la Hague died on the day of his arrival, Saint Aloüarn, after a phase of recovery, on October 27, 1772 of its consequences. His travel report was sent to the crown, but the claim to property in Western Australia mentioned therein was never to be redeemed.

Second South Sea expedition 1773–1774

Meanwhile Kerguelen had returned to France and was celebrated there as the discoverer of the long sought-after southern continent, the country in which Gonneville had been so hospitable and which he called France australe , the France of the south . He described it in the most blooming colors, although he hadn't set foot there and couldn't know the report of the landing party. He was awarded the Order of Saint Louis and promoted . The latter in particular gave him some enemies in naval circles, especially those who had also hoped for promotion but had been overlooked. At the same time, allegations surfaced that he had abandoned Saint-Aloüarn and his landing party and returned to France under the pretext of a damaged ship to claim the fame of the discovery for himself.

Nevertheless, Kerguelen received the order for a second, in-depth expedition. On March 26, 1773 Kerguelen ran from Brest with the flagship Roland and the frigate L'Oiseau under Charles de Rosnevet. This time, too, the Île de France should be the first stage destination and starting point for further activities.

From there, Kerguelen should first set a course for the island of Nutegat ( i.e. the Prince Edward Islands) and find a landing site there. The next destination should be the place where Fortune and Gros Ventre lost sight of each other during the first expedition . From there, the newly discovered land should be explored and recorded. In particular, you should look for a suitable place to set up a branch and, if possible, set it up immediately. After completing this work, the expedition should then turn to the east. Between the fortieth and sixtieth degrees of latitude , she should look for more land, looking south if possible. Kerguelen should stay away from New Zealand , Van Diemens Land or any ports in the South Seas. The return journey was to take place via Buenos Aires , which at the time was still part of the Spanish colonial empire . Its Spanish governor should also support Kerguelen if necessary, which was not a problem, as Spain and France were on friendly terms with each other through the Bourbon house contracts .

The naturalist Jean-Guillaume Bruguière was on board as a biologist and pharmacologist, and a student of Jérôme Lalandes as an astronomer : Joseph Lepaute Dagelet, who would later take part in La Pérouse's circumnavigation and perish along with the other participants. Dagelet was helped by a younger student named Manche, who would throw himself overboard in a fit of madness on the return journey. The participation of the two led to significantly better measurement results than on the first trip, and incorrect coordinates from the first trip could also be corrected.

The trip was not a lucky star from the start. The expedition had to be interrupted for forty days in Cape Town, as spoiled food and rotten water had weakened the crew. On the way, the ships got caught in a storm and the Roland was damaged. On his arrival in Port Louis, Kerguelen discovered that the situation there had changed. Governor des Roches and administrator Poivre, who had actively supported his first expedition, had been replaced. Their successors, Governor d'Arsac de Ternay and administrator Maillart Du Mesle, opposed the matter and made it difficult for Kerguelen to get fresh food and to repair his damaged ships. Instead of the 34 men he had to replace for health reasons, he was only assigned sailors who were demoted or who were also in poor health. However, Ternay had gone through a change of heart when asked whether it would be worth visiting the archipelago. Shortly after taking office in 1772, he initially had the idea of equipping a ship himself, the Belle Poule , which was already on a research voyage in the Indian Ocean, and sending Kerguelen afterwards, but then employed it elsewhere. After the return of Saint Aloüarn the plan was changed. Instead, the Gros Ventre , accompanied by the Brigantine Nécessaire , was to take on this in November 1772. However, the plans were not implemented, possibly due to the somewhat surprising death of Saint Aloüarn.

On the other hand, the group was now expanded by a third ship, the corvette Dauphin under Captain Ferron, who had already served on the North Atlantic voyage under Kerguelen. Rosily-Mesros, whom Kerguelen had dropped off on the first voyage and was unable to take up again, had also heard of the new expedition and had traveled to Kerguelen on the Île de France to see him.

Despite all difficulties, Kerguelen's expedition continued. On November 27, the ships came to the place where the Prince Edward Islands were supposed to be, but could not find it due to incorrect coordinates. Since the requirement was not to dwell too long in the search, the journey was continued quickly. On December 14, 1773, the ships reached the archipelago again. A suitable landing site could not initially be found. The ships then began to explore both the coast and the offshore islands and take various measurements. A small rocky island far to the northwest was designated as a meeting point in the event that the ships should lose contact with each other, which was initially given the name Île de Réunion , but shortly afterwards was referred to as Ilot du Rendez-Vous .

The weather conditions were again difficult on most days. Despite rain, snow, hail and stormy winds, a number of islands in the north of the archipelago, including Croÿ and Roland, today summarized as Îles Nuageuses , were mapped, mapped and named by January 16 . It was not until January 6 that Rosnevet managed to drop a group by boat in a bay that is now called Baie de L'Oiseau , which also reached the beach and was able to kill a sea lion and several penguins as provisions. This time, too, it was a younger officer, Henri Pascal de Rochegude , who deposited a certificate in a bottle at the landing site and thus officially took possession of the area on behalf of France. Kerguelen himself never set foot on the islands that bear his name today.

After the inhospitable conditions finally forced Kerguelen to abandon the company, he set course for the Bay of Antongil on the island of Madagascar . There he not only replenished his supplies, but also assisted the adventurer Moritz Benjowski in his attempt to establish a base on behalf of and on behalf of France. Then the ships sailed back home. On September 8th they anchored in Brest.

After Kerguelen's return to France at the latest, it must have become clear to anyone interested that he had only discovered a barren, uninhabited group of islands - perhaps of scientific interest, but without any economic value - and that the existence of a southern France had proven to be a pipe dream. Eventually he was brought before the court-martial , abandoned part of his crew on a desert coast, hid a stowaway on board (meaning Kerguelen's sixteen-year-old lover Louise Louison Séguin, whom he had secretly had aboard), illicit trafficking on board of a warship and to have told the untruth about the nature of the discovery made on its first voyage. Incidentally, he was essentially responsible for the failure of the second expedition.

The process took place in a strongly polarizing atmosphere. Since the preferential treatment after the first voyage, he has already been criticized in naval circles. A number of those involved took the opportunity to gloss over their part in the failure of the entire idea and to blame Kerguelen as a whole. But there were also neutral or benevolent statements. Rosily Mesros, who was left behind by Kerguelen and taken up by Saint Aloüarn, who was promoted to Vice Admiral during the Napoleonic Wars and who was to receive a plaque of honor on the triumphal arch in Paris after his death , wrote a letter to support Kerguelen. Bruguière described the difficulties he faced on his journey and deplored the missed opportunities to gain further knowledge, but at the same time defended Kerguelen from unjustified accusations. The trial finally ended in a guilty verdict on May 15, 1775. Kerguelen, losing his rank, was expelled from the Navy and sentenced to six years in prison.

Later years

Kerguelen had to serve his sentence in Saumur Castle . The conditions there weren't too harsh. Kerguelen was allowed to take his servant, a ten-year-old dark-skinned boy whom he had acquired as a slave in Madagascar, to Saumur. He used the time and began to write his travel reports about the South Sea expeditions. He was released early in August 1778. He then equipped the Comtesse de Brionne in Rochefort and participated with them as a pirate , with some success, in the American War of Independence .

In 1780 he decided to give up this business and instead set out on a scientific circumnavigation of the world. He applied for and received a letter of safe conduct from the British Admiralty for the territory of the British Empire, issued June 30, 1780 and valid for four years. On July 16, 1781 he set sail from the port of Paimbœuf at the mouth of the Loire with the Liber Navigator . The very next day his ship was boarded by the Alfred , a British privateer under the captain Thomas Walker, and brought to the Irish port of Kinsale , despite the letter of safe conduct . He himself was briefly imprisoned there, but was soon able to return to France on a passenger ship. A lawsuit before a British court was unsuccessful: Kerguelen was accused of not pursuing scientific, but rather economic interests. His aim had been to deal with customs regulations with contraband on board, to have an eye on speculation and also to have planned attacks on British colonies such as St. Helena . He had thereby violated the provisions of the letter of safe conduct. The ship and the goods were confiscated.

In the period that followed, Kerguelen shifted his activities to the field of writing. In 1782 he published a work in which he presented the travel reports of his two South Sea expeditions, together with a number of other short essays, mainly dealing with topics related to seafaring. In it he described the difficulties he faced on the second trip, including the horse and rider. The book should also serve to justify the decisions he made during the trip.

Another report from the second expedition was also published in 1782, written by Pierre de Pagès (1748–1793), who had taken part in the voyage on the Roland . Although in itself very detailed, this book did not deal with Kerguelen's difficulties at any point, and his name, who was the leader of the expedition, was never mentioned. Kerguelen's name did not appear on the attached card either. Both of these met with a certain amount of astonishment outside of France. Pagès' report was translated into several languages in the following years. Kerguelen's work, on the other hand, was banned by order of the king in May of the following year and therefore remained largely unknown. Kerguelen continued, but ultimately in vain, to have his trial reopened with the aim of rehabilitation.

With the rise of the French Revolution , Kerguelen supported their ideas. Accordingly, he joined the National Guard in Quimper in 1790 . In the following years he tried harder to be accepted back into the Navy, but initially without success. His wish was not to come true until early 1793.

As a result of the revolution, although to a lesser extent than among the land troops, a number of officers of noble descent in the French navy either deserted and fled or were dismissed because of unreliability. The successors often lacked training and experience. At the beginning of the First Coalition War in 1792 this was not a major problem because the first opponents were primarily land powers, but this changed at the beginning of the following year. The execution of the former King Louis XVI. in January 1793 indirectly led to other states joining the war. These now also included designated sea powers, such as Great Britain , on which France declared war in February. Because of this fortune that was favorable for him, Kerguelen, who, because of his previous history, was not regarded as part of the Ancien Régime , but as a victim of the Ancien Régime , was reassigned to the Navy and promoted to Rear Admiral in May of the same year . Kerguelen was assigned to the squadron of Vice Admiral Morard de Galles in Brest. De Galles, although also of aristocratic origin, had agreed to serve under the new government and, with over three decades of experience at sea, had also been tasked with restructuring the Republican Navy.

During spring and summer, de Galles' fleet, including Kerguelen , gradually assembled on board the Auguste liner off the Quiberon peninsula . Their task was to prevent a suspected landing of royalist troops. In addition, it should ensure that food transports from across the Atlantic, which had crossed the ocean in convoy, could also safely reach French ports. At that time France was heavily dependent on grain deliveries, especially from the USA. The Royal Navy, in turn, had the task of preventing this and enforcing a sea blockade . The area of operation of the French ships was between the Belle-Île and the Île de Groix . Although a fleet of British ships under Lord Howe also operated off the French coast, there were no major incidents.

In the course of late summer, resentment spread among the crews of the French ships. The forced inactivity, inadequate equipment of the sailors, the food, which, although the home coast was constantly in sight, consisted primarily of salted food, which led to the spread of scurvy - a mutiny was about to break out. To avoid this, representatives of the crews and the commanding officers agreed at the end of September to return to their home port. On the 29th the ships anchored in Brest.

In this phase of the French Revolution, the young republic had to struggle with internal opponents and problems: Royalists and Girondists had recently handed over the naval port of Toulon to the British ; an economic crisis with sharply increased prices for food and everyday goods had led to the maximum laws ; the Vendée uprising was in full swing. The year of the reign of terror had begun. Against this background, Morard de Galles was removed from his position and those officers and seamen were imprisoned who were believed to be unreliable and who were held responsible for the events of Quiberon. Some were summoned to the Revolutionary Tribunal and then executed, while others were given punishments. Kerguelen was also temporarily in prison. The fact that he was in charge of the reorganization of the military ports in Brest and Cherbourg in general and the investigation of the events of Quiberon in particular, about the content of the final report and the to measures to take. Kerguelen survived this time unscathed and returned to his post in the Navy, now under Morard de Galles' successor, Vice Admiral Villaret-Joyeuse . He had received his position in November 1793, among other things, because his ship was one of the few on which no mutiny had taken place before Quiberon.

At the end of 1794 it was planned that Kerguelen should sail with a fleet of 6000 soldiers to the Île de France (Mauritius) in order to put the island in a defensible state. This project was then postponed until further notice in favor of the rebuilding of a fleet in the meanwhile recaptured port of Toulon. Kerguelen took part in various operations in 1795 without leaving a lasting impression. After a management reorganization in Brest, he was retired in 1796.

Also in 1796 Kerguelen published a two-part work which he sent to the Directory . In this he dealt on the one hand with the history of the naval war against Great Britain between 1778 and 1783 as a result of France's entry into the American War of Independence . The second part dealt with the events since 1793. In this, he criticized the decisions of the Admiralty in these years, but at the same time gave recommendations on how the French navy could find its way back to old strength and win the war. Since he was considering how a landing in England could best be accomplished, his proposals also attracted attention abroad.

Kerguelen disagreed with his departure and tried to return to active service. In the course of these efforts, after a short, serious illness, he died on March 3, 1797 in Paris.

Naming of the archipelago

Already in November 1772 was James Cook on the journey to his second circumnavigation with a stay at the Cape Colony from the local governor Joachim van Plettenberg initial information on Kerguelen discovery. Since the information with "southern latitude 48 °, same meridian as Mauritius" was not only very sparse, but also wrong, especially with regard to the longitude, Cook was unable to visit the islands during the onward journey. On the return journey in March 1775, also at the Cape, he met Jules Crozet , who had safely brought Marion du Fresne's South Sea expedition back to Mauritius after his death in New Zealand . He handed Cook a card that contained both his own and Kerguelen's first voyage discoveries.

For his third circumnavigation of the world, Cook received the explicit order from the British King to visit the islands discovered by the French. About a month after his departure Cook had luck on his first stop in August 1776 in Santa Cruz de Tenerife on Jean-Charles de Borda to meet. The crew of Borda's ship Boussole also included a helmsman who had made Kerguelen's second voyage. He was able to give more precise information about the location of the rocky island Rendez-Vous , and so Cook managed to locate the archipelago on Christmas Eve 1776. However, neither Crozet, Borda nor the helmsman had informed him that Kerguelen had made a second trip to the islands and also visited the north coast, which Cook had now also visited. Unaware of this voyage, Cook gave the corresponding sections of his coastline with his own names. The bay, which Rosnevet had also used for landing three years earlier and which he had called Baie de L'Oiseau , was named Christmas Harbor by Cook on the current occasion .

On December 27, however, a member of Cook's crew discovered the document Rochegude had left in a bottle in the bay. Cook added another entry to his own visit, sealed it, and put it back in place. Knowing that this was the island that Kerguelen had discovered before him, he gave it its name in order not to rob him of the fame of the first discovery. Cook noted in his expedition report at the same time that he might as well have called it Island of Desolation because of its sterility.

"... which, from its sterility, I should, with great propriety, call the Island of Desolation, but that I would not rob Monsieur de Kerguelen of the honor of its bearing his name."

Works

Original works

- Relation d'un voyage dans la mer du Nord en 1767-68. Amsterdam and Leipzig, 1772. Digitized at Google Books (French).

- Relation de deux voyages dans les mers australes et les Indes, faits en 1771, 1772, 1773 et 1774. Paris 1782. Available in digital form on the website of the Bavarian State Library (French).

- Mémoire sur la Marine, adressé à l'Assemblée nationale. Imprimerie de Léonard Danel, 1789. Digitized by Gallica (French).

- Relation des combats et des événements de la guerre maritime de 1778 entre la France et l'Angleterre, mêlée de réflexions sur les manœuvres des généraux: précédée d'une adresse aux marins. sur la disposition des vaisseaux pour le combat: et terminée par un précis de la guerre présente, des causes de la destruction de la marine, et des moyens de la rétablir. Paris 1796. Available in digital form on the website of the Bavarian State Library and from Gallica (French).

Translations into the German language

- Herr de Kerguelen Tremarec's description of his voyage to the North Sea which he made in 1767 and 1768 to the coasts of Iceland, Greenland, Faroe Islands, Shetland, the Orkneys and Norway. Published as the twenty-first and last volume of “General History of Travel on Water and Land, or Collection of All Travel Descriptions” . Leipzig, 1774. Digitized at the Open Library.

literature

- Isabelle Autissier: Kerguelen, le voyageur du pays de l'ombre. Paris, 2006, ISBN 2-246-67241-4 (French)

- Gracie Delépine: L'Amiral de Kerguelen et les mythes de son temps . Paris, Montreal, 1998, ISBN 978-2-7384-6680-8 (French)

- John Dunmore: French Explorers in the Pacific. Vol. 1: The Eighteenth Century. Herein the section on Kerguelen, pp. 196–249, Oxford 1965, ISBN 978-0-19-821529-5 (English)

- Marthe Emmanuel: La France et l'exploration polaire: De Verrazano a la Pérouse 1523-1788. Paris 1959, ISBN 2-7233-1203-8 (French)

- Philippe Godard: The Saint Alouarn discoveries. The Australian Association for Maritime History, Quarterly Newsletter No. 77, December 1999, p. 8 f. Digitized version ( memento from April 20, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), PDF file, 951 kB (English)

- Pétur Hreinsson: Fyrsti erlendi vísindaleiðangurinn til Íslands. Um leiðangra Kerguelen Trémarec til Íslands árin 1767 og 1768 (The first foreign scientific expeditions to Iceland. About the expeditions of Kerguelen Trémarec to Iceland in 1767 and 1768). Final thesis to obtain a Bachelor of Arts in history. Reykjavík, September 2013. Digitized at skemman.is, the joint document server of several Icelandic universities. PDF, 315 kB (Icelandic)

- Jean-Paul Morel: Les missions de Kerguelen dans l'océan India (1771-1774) . Digitized on a website about the life and work of Pierre Poivre , PDF, 194 kB (French)

- Pierre Marie François de Pagès: Voyages autour du monde, et vers les deux poles, par terre et par mer. Report of a participant in the second expedition in 1773/74, published in different editions, languages and under different titles and subtitles, for example:

- Pendant les années 1767, 1768, 1769, 1770, 1771, 1773, 1774 & 1776. Tome second, Paris 1782, p. 5 ff. Digitized at Archive.org (French)

- Travels round the world in the years 1767, 1768, 1769, 1770, 1771. (sic) Volume 3, London 1792, pp. 1-142. Digitized at Archive.org (English)

- Mr. de Pagès Königl. French ship's captains, knight of the St. Ludwig order, correspondent of the Academy of Sciences in Paris, traveling around the world and to the two Poles by land and sea in the years 1767, 1768, 1769, 1770, 1771, 1773, 1774 and 1776, Frankfurt and Leipzig 1786, pp. 459-578 Digitized at the SLUB Dresden. , Skip to the section

- Alexis – Maria de Rochon: Travels to Morocco and India from 1767 to 1773 . In: Matthias Christian Sprengel, Theophil Friedrich Ehrmann (Hrsg.): Library of the latest and most important travelogues to expand geography. Volume 10, Part 2, Weimar 1804, pp. 86 ff. Go to section .

- Biography Kerguelen-Trémarec in: Prosper Levot, A. Doneaud: Les gloires maritimes de la France. Paris 1866, pp. 258-260. Digitized at Google Books, directly to the side , alternative version on a private website (French).

Web links

- French navigators of the eightteenth century on a website about the great explorers

- Information on the first South Sea expedition on the Museum of Western Australia website

- Kerguelen in Iceland 1767 and 1768 . Exhibition from 2014 on Kerguelen's two trips to Iceland on the website of the National and University Library of Iceland (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Genealogy of the family at genea.net, accessed on October 28, 2012 (French).

- ↑ genealogy of the son at genea.net, accessed on 28 October in 2012 (French).

- ↑ See Gunlaugsson's map from 1844 and the topographic map 1: 100,000 from 1934 .

- ↑ a b Seymour Chapin: The Men from across La Manche. French Voyages 1660-1790. P. 111 f. In: Derek Howse (ed.): Background to Discovery: Pacific Exploration from Dampier to Cook. Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford 1990, ISBN 0-520-06208-6 , pp. 81-128 (English). Digitized at Google Books, right to the side

- ↑ Location of the islands on an IGN map . Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- ^ Récit de Charles Marc du Boisguehenneuc sur la prize de possession des Iles Kerguelen. In: kerguelen-voyages.com. Retrieved December 10, 2015 (French).

- ↑ a b Denis Piat, Patrick Poivre D'Arvo: Mauritius on the Spice Route, 1598-1810. Singapore 2011, ISBN 981-4260-31-2 , p. 185. Preview on Google Books , (English).

- ↑ Information about Saint Aloüarn in connection with maritime archeology on the website of the Museum of Western Australia. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ↑ Information about Saint Aloüarn as part of an exhibition about great voyages of discovery on the website of the Museum of Western Australia. Retrieved October 22, 2012.

- ↑ a b Letter from the Governor d'Arsac de Ternay to the responsible ministry dated October 19, 1772, digitized version , PDF file, 25 kB. Retrieved November 28, 2014 (French).

- ^ A b Entry Jean-Guillaume Bruguière in: David M. Damkaer: The Copepodologist's Cabinet: A Biographical and Bibliographical History. Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society. 2002, ISBN 978-0-87169-240-5 , p. 104 ff. (English)

- ↑ Comparison of previous and present names on a website about the Kerguelen Islands. Retrieved October 22, 2012.

- ^ Location of the island on the IGN topographical map . Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ↑ Location of the bay on the IGN topographic map . Retrieved October 22, 2012.

- ^ Jugement du Conseil de Guerre. In: kerguelen-voyages.com. Retrieved December 10, 2015 (French).

- ↑ Les catégories de détenus à Saumur . Article on the different categories of prisoners at Saumur Castle on a website about the city, accessed on November 2, 2012 (in French).

- ^ Condemnation of the ship "The Liber Navigator" . The Political Magazine and Parliamentary, Naval, Military, and Literary Journal, July 1782, p. 732. Digitized from Google Books, accessed October 26, 2012.

- ^ A b James Cook: A voyage to the Pacific ocean. Undertaken, by the command of His Majesty, for making discoveries in the Northern hemisphere, to determine the position and extent of the west side of North America; its distance from Asia; and the practicability of a northern passage to Europe. Performed under the direction of Captains Cook, Clerke, and Gore, in His Majesty's ships the Resolution and Discovery, in the years 1776, 1777, 1778, 1779, and 1780. Volume I, London 1784, p. 83. Digitalisat available in der Open Library, right to the side

- ↑ Johann Ludwig Wetzel: Captain Cook's third and last voyage, or story of a voyage of discovery to the calm ocean, which on the orders of Sr. Great Britain's Majesty undertook to explore the northern hemisphere more closely. Ansbach 1787, p. 120 f. German translation of Cook's travelogue, published in 1984, digitized available at the Göttingen Digitization Center .

- ^ William James: The Naval History of Great Britain, from the declaration of war by France in 1793, to the accession of George IV. New edition, Vol. I, London 1902, pp. 60 ff. (English) Digitized in the Open Library, right to the side

- ↑ James, Naval History, p. 135, directly to the side .

- ↑ On the prehistory of the naval battle on the Glorious First of June ( memento from August 1, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) on Thomas Siebe's website about the European naval wars between 1775 and 1815, accessed on November 4, 2012.

- ^ Short biography of Vice Admiral Louis Thomas Villaret-Joyeuse ( Memento of March 14, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) on Thomas Siebe's website about the European naval wars between 1775 and 1815, accessed on November 4, 2012.

- ↑ James, Naval History, p. 258, directly to the side

- ↑ Minerva , Volume IV, Hamburg 1796, p. 152 f. Digitized at Google Books, go to section

- ↑ Wetzel: Capitain Cook's third and final journey. P. 80 ff.

- ↑ Wetzel: Capitain Cook's third and final journey. Introduction, p. XXXVIII f.

- ↑ Wetzel: Capitain Cook's third and final journey. P. 95 f.

- ↑ Wetzel: Capitain Cook's third and final journey. P. 119 f.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Kerguelen de Trémarec, Yves Joseph de |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French navigator and explorer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 13, 1734 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Landudal |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 3, 1797 |

| Place of death | Paris |