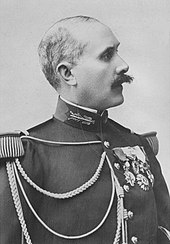

Armand du Paty de Clam

Armand Auguste Charles Ferdinand Marie Mercier du Paty de Clam (born February 21, 1853 in Paris - † September 3, 1916 ), usually listed in the literature as Armand du Paty de Clam, was a French professional soldier who played a key role in the Dreyfus Affair was involved.

Life

Armand du Paty de Clam was a graduate of the Saint-Cyr Military School and the École d'état major . During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 he joined the army at the age of seventeen. He was appointed major in 1890 and appointed to the General Staff as an officer in 1894. There he became deputy head of the Troisième Bureau, one of the four departments in the War Ministry. Armand du Paty de Clam's historical significance lies in his role during the Dreyfus Affair. This began when, on September 25, 1894, the cleaning lady Marie Bastian stole a torn and unsigned letter from the wastebasket of the German military attaché Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen and delivered it along with other fragments of paper to the French intelligence service, which regularly paid her for such services .

The letter, the so-called bordereau , was a letter accompanying a delivery of five secret documents to Schwartzkoppen. The betrayal of secrets was not particularly serious, but for the intelligence service the letter was evidence that an officer of the General Staff was delivering information to foreign powers. On the basis of a superficial comparison of manuscripts, the Jewish artillery captain Alfred Dreyfus was suspected to be the culprit . Paty de Clam was commissioned by the then Minister of War, Auguste Mercier, to carry out the preliminary investigation.

On October 15, Dreyfus was summoned to the Chief of Staff under a pretext and asked by Paty de Clam to handwrite the sentences he said. These were words and scraps of sentences from the intercepted bordereau. After the dictation, Dreyfus was arrested and taken to Cherche-Midi prison. Dreyfus's house was searched immediately afterwards. Paty de Clam informed Alfred Dreyfus' wife Lucie that her husband had been arrested, but refused to give her any further information. He also warned her not to tell anyone about the arrest and threatened that such information would have serious consequences for her husband. It was not until October 28 that she was allowed to notify the other family members of the arrest.

Armand du Paty de Clam came to the conclusion in the course of his preliminary investigation that the evidence would not be sufficient to convict Alfred Dreyfus. Apart from the bordereau and the inconclusive manuscript comparisons, there was no further evidence. There was also no motive for treason by Alfred Dreyfus. Lack of money - one of the classic reasons for treason - did not apply to the wealthy Dreyfus. He had neither women's stories nor gambling debts, but was happily married and the father of two young children. Paty de Clam came to the conclusion at the end of October that the evidence would not be sufficient to obtain a conviction of Alfred Dreyfus in court.

Just two days after Paty de Clam informed Chief of Staff Raoul Le Mouton de Boisdeffre that he had doubts that the lawsuit would be successful, an informant from the War Department released details of the case to the press. War Minister Mercier was now in a difficult position. Had he ordered Dreyfus to be released, the nationalist and anti-Semitic press would have accused him of failure and a lack of hardship towards a Jew. If, on the other hand, Dreyfus were acquitted in a trial, he would have been accused of having made reckless and dishonorable accusations against an officer in the French army and of risking a crisis with Germany. Mercier would then probably have had to resign. At a special session of the Cabinet, Mercier showed the ministers a copy of the bordereau, which he claimed was clearly written by Dreyfus. The ministers agreed to initiate an investigation into Dreyfus. The case was thus handed over to General Saussier, who on November 3rd entrusted Captain Bexon d'Ormescheville with the further preliminary investigation. He was an exam judge at the Premier conseil de guerre in Paris. However, Du Paty was still preoccupied with the case. Together with Major Hubert Henry he prepared a secret dossier in which the following was put together:

- Schwartzkoppen's fragmentary memorandum to the General Staff in Berlin, in which he obviously weighs up the advantages and disadvantages of working with an unnamed French officer who offered his services as an agent.

- A letter from the Italian military attaché Alessandro Panizzardi, which he had written to his close friend Schwartzkoppen on February 16, from which it can be read that Schwartzkoppen passed on espionage material to Panizzardi.

- A letter from Panizzardi to Schwartzkoppen, in which he wrote that "cette canaille de D" (this Kanaille D.) had given him plans for a military facility in Nice so that he could forward them to Schwartzkoppen. This reference, which Major Hubert Henry , who was involved in the compilation of the secret dossier, knew very well, to a cartographer from the War Department who had been selling plans of military facilities to the two military attachés for years.

- A message from the Marquis de Val Carlos to Major Hubert Henry, in which he pointed out that Schwartzkoppen had a French officer as an agent.

Jean Sandherr, the head of the intelligence service, also instructed Paty de Clam to prepare a comment for the secret dossier that would establish a link between these documents and Dreyfus.

During the trial of Dreyfus before the court martial , the judging officers were illegally transmitted this secret file without the knowledge of the accused or his lawyer. The judges ultimately passed their verdict under the influence of this secret material.

When Jean Sandherr's successor in the post of head of the intelligence service, Lieutenant Colonel Marie-Georges Picquart , was able to identify the actual traitor Ferdinand Walsin-Esterházy by chance in 1896 , Paty de Clam was involved in the cover-up attempts. This included warnings to Esterhazy and other forgeries that were supposed to ensure that Alfred Dreyfus' error of justice was not discovered. After the affair was cleared up, Paty de Clam was arrested like Major Hubert Henry. While Henry committed suicide in the cell after confessing his forgeries, Paty de Clam was released for lack of evidence. In 1905 he retired. In 1914 he returned to active service and fought in a regiment commanded by his son Charles du Paty de Clam during the First World War. In 1916 he succumbed to a war wound. His son became head of the Vichy Department of Jewish Affairs in 1943 .

literature

- Louis Begley : The Dreyfus Case: Devil's Island, Guantánamo, History's Nightmare. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 2009, ISBN 978-3-518-42062-1 .

- Léon Blum : Summoning the Shadows. The Dreyfus Affair. From the French with an introduction and a note by Joachim Kalka. Berenberg, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-937834-07-9 .

- Ruth Harris: The Man on Devil's Island - Alfred Dreyfus and the Affair that divided France. Penguin Books, London 2011, ISBN 978-0-14-101477-7 .

- Elke-Vera Kotowski , Julius H. Schoeps (Eds.): J'accuse…! …I accuse! About the Dreyfus affair. A documentation. Catalog accompanying the traveling exhibition in Germany May to November 2005. Published on behalf of the Moses Mendelssohn Center . Verlag für Berlin-Brandenburg, Potsdam 2005, ISBN 3-935035-76-4 .

- George Whyte : The Dreyfus Affair. The power of prejudice. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2010, ISBN 978-3-631-60218-8 .

Single receipts

- ↑ Kotowski et al., P. 30

- ↑ Whyte, pp. 40-41

- ↑ Whyte, S: 45

- ↑ Begley, p. 24

- ↑ Begley, p. 25

- ↑ Whyte, pp. 45-47

- ↑ Whyte, p. 18

- ^ Harris, p. 30

- ↑ Begley, p. 26

- ↑ Whyte, pp. 51-52

- ↑ Whyte, p. 52

- ↑ Whyte, p. 573

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | You Paty de Clam, Armand |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Du Paty de Clam, Armand Auguste Charles Ferdinand Marie Mercier (full name); You, Armand (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French professional soldier |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 21, 1853 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Paris |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 3, 1916 |