Foreign policy of the North German Confederation

The foreign policy of the North German Confederation , the first German nation-state, was determined primarily by Prussia . Prussia was not only by far the largest member state in the North German Confederation ; In spring 1870 the Prussian Foreign Office was elevated to the Foreign Office of the North German Confederation. The most important politician of the federal government was Otto von Bismarck , the Prussian Prime Minister and Foreign Minister .

From the founding in 1867 to the merging of the larger German Empire on January 1, 1871, the relationship with the southern German states and France was decisive. Bismarck tried to bind Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden and the Grand Duchy of Hesse closer to the federal government. But he was reluctant to ignite a real popular movement in the south, also because he then feared a strengthening of the liberal national movement.

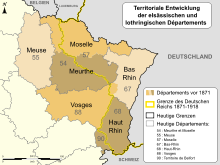

France's Emperor Napoleon III. until 1866 had been benevolent to the Prussian cause. After the federal founding, however, diplomatic crises quickly developed. A kind of cold war arose between northern Germany and the French Empire. In July 1870 one of the diplomatic crises, the question of the Spanish succession to the throne , led to the Franco-Prussian War . During the war the southern states joined the north and Alsace-Lorraine was annexed. With the constitution of the German Confederation of January 1, 1871, the North German Confederation ended.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Since 1867 Otto von Bismarck was the North German Chancellor, appointed by King Wilhelm, the holder of the Federal Presidium . First he set up a Federal Chancellery . The liberals in the Reichstag also called for further federal authorities, while Bismarck wanted to prevent regular ministries or even a collegial government. After all, the Prussian Foreign Ministry was transferred to the federal government as the Foreign Office on January 1, 1870.

Similar to 1848/49 , the question arose whether only the North German Confederation could appoint and receive envoys. The opinion prevailed that the individual states continued to retain their own legation rights. Because of the cost alone, there were fewer and fewer such ambassadors over time. The legation law of the individual states remained of little importance in practice.

Situation after the foundation of the federal government

Relationship to the southern German states

The Peace of Prague of August 23, 1866 ended the war between Prussia and Austria. The contract provided for the possibility that

- Prussia and the other states north of the Main unite: The North German Confederation was founded on July 1, 1867 as a federal state ;

- and that the southern German states form a federation of states , a southern German federation .

The northern German federal state and the southern German confederation could have worked together in another federation. This further federation would have served the military protection of the southern states, as a replacement for the German federation. Due to disagreement in and among the southern German states, the southern league did not come about. Instead, Prussia signed individual treaties with the respective southern states, the so-called protective and defensive alliances .

Bismarck considered making the German Customs Union an instrument of German unity. At a meeting in 1867, the Zollverein was reinforced by new institutions: a Federal Customs Council and a Customs Parliament. The change came into effect on January 1, 1868. In that year, the southern German members of the Customs Parliament were elected, while the northern German members were the members of the northern German Reichstag . The Zollverein standardized trade policy in almost all of Germany and in this way prepared German unity. Bismarck was disappointed, however, by the outcome of the southern German customs parliamentary election in 1868 , as it was mainly Prussia's opponents who were elected.

In February 1870 there was a memorable incident in the Reichstag: With the Lasker interpellation , the National Liberals had called for liberal and nationally conscious Baden to be included in the federal government. This would put pressure on the other southern states. Chancellor Bismarck replied sharply dismissively that the time was not ripe for this and that he or the Federal Presidium would not allow himself to be pushed. Ultimately, Bismarck feared that such accession would have strengthened the liberals and called for a more liberal constitution.

Austria-Hungary

The multiethnic Austria was only partially able to act after the defeat of 1866, the Compromise with Hungary of 1867 was not a satisfactory solution: The understanding between the Germans and the Hungarians came at the expense of the Slavs; Even the Germans disagreed among themselves on how to proceed after the defeat.

Emperor Franz Joseph appointed Friedrich Ferdinand von Beust as Chancellor, the former Saxon minister and opponent of Bismarck. Despite the dissolution of the German Confederation, the Austrian leadership strove to regain more influence in southern Germany. In addition, Austria's position in Central Europe was to be expanded with the help of alliances. After Prussia showed no interest in cooperation, Austria-Hungary turned to France. However, this met with reluctance from many southern Germans and German-Austrians, only the Czechs had sympathy for France. The Hungarians strictly rejected a "re-entry into Germany".

The Austro-Hungarian dual monarchy sought an alliance with France and Italy from 1868 to 1870 . It did not materialize because of different goals: France primarily sought support against Prussia, but Austria-Hungary against Russia.

France

The foreign policy of the French emperor Napoleon III. was sometimes changeable and is interpreted differently today. Within his Napoleonic reasons of state, the pursuit of prestige, power and indirect influence, he tried to activate the nationality principle and thus to use the favorable situation in which France had found itself since the Crimean War . In his propaganda he presented this as a policy of unifying a modern, nation-state Europe. Napoleon thought of the liberation of the peoples in the Balkans from foreign Ottoman rule, of a re-established Poland, of a new order in Italy and Germany - as long as this served French interests. Critics in France themselves feared the momentum of unleashed nationalities.

During the Crimean War he wanted to see Germany divided into three parts, in the Italian War he thought of dividing Austria, with which he ultimately came to terms. Napoleon learned that Prussia and the German Confederation had stood in his way during this time. Around 1860 he began to try to get closer to Prussia politically and economically. The French press described Prussia as a modern liberal constitutional state. This was directed against Austria-Hungary, which was seen as an arch enemy with hegemonic aspirations.

Napoleon favored the German War of 1866 in order to weaken the German Confederation (founded against France) and the two German great powers. Similar to what he had planned for Italy in 1860, he thought of a Germany divided into three parts: In a secret treaty with Austria he had stipulated that Austria-Hungary could only implement a new order with French consent. At best, Prussia was supposed to expand into northern Germany. Last but not least, Napoleon relied on the German medium-sized states. Since he was assuming a victory for the Austrian central states, he refrained from making concrete agreements with Prussia. After Prussia's victory, Napoleon, cheated of his hopes, had to accept the new situation, as French troops were still in Mexico and Algeria. Intervening would also have contradicted the propagated principle of nationality.

Napoleon then sought a compromise or even an alliance with Prussia in order to withdraw it from Russian influence. Public opinion, however, remained hostile to Prussia and expected at least the acquisition of smaller Prussian territories (borders of 1814) in view of the great annexations of Prussia in northern Germany. The connections between northern and southern Germany, namely the protective and defensive alliances and the customs parliament, appeared to many French as crossing the Main line, as established by the Peace of Prague. Napoleon's great power policy had failed. In the years to come, France did not succeed in forging an alliance directed against northern Germany. The emperor saw his "crisis-prone system" more and more criticized by public opinion. Konrad Canis: “Apparently, many of the politically ambitious French were not only convinced that their state was rightly dominant in Europe, but also demanded to assert it aggressively. The unstable regime was unable to escape this pressure. "

Russia

The Russian Empire had had good connections with the Kingdom of Prussia for a long time . Not only had Prussia remained neutral in the Crimean War, it was on Russia's side in 1863 when Russia put down the Polish uprising . As a result, any intervention by the Western powers, which Russia had feared, became completely impossible. The Russian benevolence that Bismarck enjoyed in the years that followed was also due to the fact that Russia considered Prussia weak.

Bismarck's aggressive policy in the German Confederation in 1866 was sharply criticized by the Russian Foreign Minister Gorchakov. Gorchakov wanted a European congress that would have solved the Veneto and Schleswig-Holstein questions. Prussia and Italy agreed to the proposal, while Austria-Hungary rejected it if Veneto had been on the agenda. Therefore, Russia was only briefly upset about the all too brash Prussia.

Russia also criticized the annexation of northern German states by Prussia , and it would have objected if Prussia had extended its power to southern Germany. Russia offered Prussia to keep Austria-Hungary in check with Russian troops at the border in the event of a French attack on Prussia. Behind this, however, was the Russian goal of dominating Central and Eastern Europe again, thanks in part to the Prussian-Austrian rivalry. However, from Russia's point of view, because of its expansion into Asia, tensions with Great Britain grew, and in the Balkans and the Mediterranean, Austria-Hungary was also the main opponent. In the spring of 1868, King Wilhelm and Tsar Alexander made an agreement: the federal states assured each other of support if Austria and France jointly attacked Prussia or Russia.

This agreement, which was not officially made, but was nonetheless very binding, was a masterpiece by Bismarck. Prussia was no longer perceived as secondary by Russia, while Russia was in a weak position. But Bismarck was also lucky that in the first half of 1870 Russian policy in the Balkans and the Middle East was cautious, an exception in that era.

Great Britain

Great Britain was not fundamentally against German unification. Despite differing views on the way there, both major parties at times even welcomed the fact that a unified economic area without customs barriers would emerge in central Europe. They also wanted a counterweight for France and Russia. Because of domestic and world political problems in the 1860s, there was no interest in London in interfering, especially in Central Europe.

For British Prime Minister Palmerston, Prussia was only on a par with France after 1866. British Prime Minister Palmerston saw Prussia as a secondary counterweight to France, the main rival on the continent. "Central Europe no longer represented the power-political vacuum that was one of the conditions for the balance of powers on the continent," said Konrad Canis.

But while Britain had few points of friction with Prussia, there was even more with France. In the summer of 1866 it was assumed that Napoleon III. wanted to enlarge his territory, in 1867 there was the Luxembourg crisis and in the following year the Belgian railways. British-French relations reached a low point. Above all, however, the British Empire caused great concern for London: So far, global “ Pax Britannica ” and parliamentarism seemed to complement and promote each other. "Now the relationship between democracy and empire [...] has become a cardinal problem in British history," says Klaus Hildebrand . A policy of non-intervention in Europe was not only popular: those responsible feared a chain reaction with threats to Britain's position as a world power.

Foreign policy crises and issues

Luxembourg Crisis 1867

After 1866, the German Confederation no longer existed, so that Luxembourg was no longer a member of any confederation. His Grand Duke was, in a personal union , the King of the Netherlands. In this situation France tried to annex the area. King-Grand Duke Wilhelm III. was ready to cede the Grand Duchy to France in exchange for money. Napoleon III believed in agreement with Prussia that he could take over Belgium and Luxembourg , as the price for his goodwill towards the Prussian expansion of power.

But Bismarck was afraid of public opinion in Germany, which would have seen the sale of Luxembourg as a betrayal of the national cause. He worked on Wilhelm III. to withdraw the offer. In France, people were outraged, the country mobilized its troops. Finally, the crisis was resolved by an international conference in London : the powers confirmed the situation and the neutrality of Luxembourg.

Belgian railway crisis 1868/1869

At the end of 1868 a French railway company , the Ostbahngesellschaft, planned to take over two financially troubled Belgian companies. The Belgian government blocked the sale through a new law that required government approval. They feared economic penetration by France. The new law outraged the French government, which required the Belgian government to give its approval. She suspected the North German Confederation of secretly preventing the acquisition.

Negotiations took place in Paris in March and April 1869. The French side insisted on their position, while Belgium was only prepared to compromise. Great Britain exerted increasing pressure on France and eventually threatened a British-Prussian alliance. Napoleon gave in and negotiated the compromise.

Imperial plan 1870

On the occasion of the establishment of the new office, Bismarck considered giving the Prussian king (the “ Federal Presidium ”) an imperial title. The king had no actual official designation for the representation of the federation vis-à-vis foreign countries, as head of the North German Confederation. The king would have refused to call himself the "President" of the North German Confederation, even if even conservative politicians sometimes used the term. Above all, however, Bismarck wanted to upgrade King Wilhelm internationally and thus bring momentum to the German question.

Bismarck was already exploring abroad and in southern Germany how an imperial title would be accepted there. The reactions were rather negative, and King Wilhelm was against a newly invented imperial title. Finally, the imperial plan was overshadowed by the crisis in the course of the Spanish succession . During the war against France, the Federal Council and the Reichstag approved a constitutional amendment that gave the Federal Presidium (the Prussian King) the title of “ German Emperor ”.

Succession to the Spanish throne 1870

In 1868 the Spanish Queen Isabella II was deposed. The revolutionary transitional regime looked across Europe for a suitable new king for Spain. After several rejections, the regime turned (again) to Leopold von Hohenzollern , a relative of the Prussian King Wilhelm. Bismarck persuaded Leopold to run for office despite the politically uneasy situation in Spain. Bismarck wanted to achieve a diplomatic victory against France, which rejected a Hohenzollern prince as Spanish king.

After the candidacy became known on July 2, 1870, the French government threatened war. Leopold withdrew his readiness. The imperial government, through its ambassador, insolently demanded that the Prussian king, the head of the House of Hohenzollern, exclude a candidate for Hohenzollern forever. King Wilhelm was against war, but refused to give such a guarantee. Bismarck published Wilhelm's reaction to the French ambassador in terms that made the rejection look very harsh.

Franco-German War 1870/1871

Outbreak of war

Bismarck's press release on the conversation between Wilhelm and the ambassador led to great outrage in Germany and France. The French declaration of war on Prussia followed on July 19, 1870. The Federal Constitution brought a state of war to all of Northern Germany.

In southern Germany, even after the declaration of war against the north, people remained skeptical, but they became convinced that only a victorious war and German unity would provide security from France. Such an external threat was absent in 1849 when Prussia first attempted a nation-state. The protective and defensive alliances with Prussia obliged the southern states to provide assistance in every war. In theory, they could have delayed the start of the war by asking who the attacker was. But some of the politicians in the southern states initiated appropriate measures such as mobilizations and war credits in parliament before the declaration of war.

The French government assumed that Denmark and Austria-Hungary wanted revenge for their war defeats of 1864 and 1866 and would enter the war of their own accord. Italy would later join France to thank them for help in previous years. Russia would remain neutral in order to prevent a united Germany. After the Triple Alliance negotiations, Napoleon believed that Italy and Austria-Hungary were morally obliged to help. In fact, France remained isolated during the war. His reason for war, the insulted honor of the nation, was hardly recognized in Europe.

Austria-Hungary and Russia

Great Britain and Russia would have liked to act as mediators. However, Bismarck had plans published in London according to which Napoleon wanted to occupy Belgium. The Tsar threatened Austria-Hungary with intervention should it support France, while his Prime Minister Gorchakov leaned towards France. Both countries still misjudged Prussia as a secondary power along with Austria-Hungary behind the three dominant great powers Russia, Great Britain and France. They liked a lasting rivalry between France and Prussia and also a weakening of France. This explains their inaction, but they wanted only a short war with minor consequences.

After the outbreak of war, the Austrian emperor and Chancellor Beust hoped to regain a little more influence in southern Germany. Instead of offering to France, it was decided to wait for French victories first. In the event of a French occupation of southern Germany, Austria-Hungary could either have negotiated a liberation with France, or liberated the south militarily with Prussia. In any case, few expected a Prussian victory, the greater the feeling of powerlessness and despair later on. Unexpectedly, southern Germany was not occupied; rather, its governments and people joined Prussia, and in Austria the German speakers showed solidarity with the German national movement. If the Viennese leadership had decided to support France or Germany, one would have to reckon with conflicts between the German-speaking and the pro-French Hungarians and Slavs. In Vienna they feared that France would stir up the Romanians in the Danube principalities. The situation there was already troubled. This could have resulted in a Russian attack, affecting the willingness of Hungarians to work towards Austria-Hungary joining the war on the French side. After all, intervention in France's favor could have led to a two-front war against Prussia and Russia. Austria-Hungary, however, was in any case incapable of waging war because of its military and financial weakness.

With reference to the new republic in France, Russia and Austria-Hungary, Bismarck tried to win sympathy for his own, conservative-monarchical cause. Another moment, however, was more effective for Russian neutrality. Russia was still subject to the terms of the Peace of Paris of 1856. With Bismarck's diplomatic support, the tsar canceled the clauses on the neutralization of the Black Sea on October 31, which had forbidden Russia to have its own battle fleet there.

After the Russian advance, a rethink also began in Austria-Hungary. The annexations in Austria-Hungary were not popular, but Beust assumed that, like the annexation of southern Germany to the north, they could no longer be prevented. With a friendly relationship with Prussia, Austria-Hungary would be able to exercise influence, at least in details.

Great Britain

After the outbreak of war, Bismarck benefited from tense British-French relations. He was angry about British protection for French citizens in northern Germany, since he was more or less confronted with a fait accompli in July 1870. In addition, the British Foreign Office took over the diplomatic business of France in Berlin and, conversely, wanted to do the same in Paris. Bismarck was suspicious of this interference and instead let the United States do the job.

The Chancellor was also annoyed by the decision of the British government that its citizens could trade with both war opponents. Had the French blockade of the Baltic Sea been successful, this seemingly impartial stance would have helped the French alone. And while overseas trade remained banned, the French were able to rent British ships in Britain to supply themselves with British goods such as coal and ammunition. Despite requests from Bismarck and even King Wilhelm, Great Britain stuck to this practice. London replied that otherwise the French would turn to America and British industry would be ruined.

Britain recognized that France had acted aggressively and declared war. However, it tried not to annoy either of the two war opponents unnecessarily. A commitment on the continent should be avoided, at least for now. Last but not least, Belgian neutrality was important for London, which he had only secured through a treaty with Prussia in August 1870, and shortly afterwards with France. This obvious equality also angered Bismarck, since France had finally started the war and had already looked at Belgium (and Luxembourg) in previous years.

Other countries

Since the beginning of the war, Italy's Foreign Minister Visconti-Venosta has made vigorous efforts to form a “ League of Neutrals ” in order to prevent the war from spreading to all of Europe. His King Viktor Emanuel II, on the other hand, was strongly pro-French and would have loved to lead Italy to war. The king reported to the Austrian ambassador about a with Napoleon III. Negotiated plan: Austria-Hungary and Italy should act as mediators. After Prussia had rejected unacceptable demands, the Triple Alliance plan of 1869 would come into play. Viktor Emanuel had to accept, however, that the majority of the cabinet offered resistance. It was only after the Prussian victory at Spicheren on August 6 that the tendency towards neutrality prevailed in Italy. Support for French policy would have made it even more difficult for the moderates in Paris to assert themselves against the warring party and to advocate a reasonable compromise with Prussia.

Denmark had been strongly anti-Prussian since the defeat of 1864 at the latest. The dynasties of Denmark and Russia were closely related, which tended to damage the Prussian cause. In addition to the Tsarina, a sister of the Danish king, the Dane Jules Hansen in Paris was anxious to influence opinions about Prussia. The PR consultant Hansen stood on the side of the French government and wanted to torpedo the Prussian-Russian agreement.

Alsace-Lorraine

In the first weeks of the war, the Germans saw that military successes were bought with great losses. All the more, they demanded greater security from France. Moving the border to the west was only enforceable if France was inflicted a complete military defeat. A short war thus became impossible, because the new French regime would have risked its own end if it had accepted the German demands.

Only a small minority, including the socialists around August Bebel , spoke out against annexations . Otherwise all classes and political directions were in favor of the integration of Alsace and Lorraine, above all the liberals. Bismarck believed that the lust for power and arrogance were peculiar to the French national character, and that France would seek revenge anyway. Therefore Alsace and Lorraine were to serve as cover to make the future attack more difficult. Wetzel emphasizes that Bismarck went to war with no intention of annexation, that he improvised, had to take public opinion into account and in doing so made a political cost-benefit calculation without changing his personal opinion. As with the colonies, he only saw in retrospect that the acquisition of the territory was not worth it.

Bismarck correctly estimated that the loss gave France an impetus, but only an additional one. However, he was also aware that the annexation signaled a threatening claim by Germany to great powers such as England and Russia. In Italy, the USA and other countries, too, the annexation plan caused a clear change in sentiment to Germany's disadvantage. Canis points out that a victorious France would certainly have demanded the Rhine border. At that time it was unimaginable that the winner would not have asked for any areas.

On September 1, 1870, the Battle of Sedan took place. Napoleon III was captured and had to surrender . Many soldiers came into German captivity , and a large part of the war material also fell into German hands. However, on September 4, a National Defense Government was formed in Paris . It was uncertain whether and how the new government would continue the war. Many French did not yet consider their country defeated. In any case, the new government refused a swift armistice, as requested by Bismarck. She kept Napoleon III. for the perpetrator of the war. After its departure, France should get a “just” peace without annexations and war reparations. The new leaders of France held onto this with almost religious certainty for the next three months, until they had to realize that Napoleon's bitter defeat was theirs too.

Transition to the German Empire in 1870

The southern German states, under the influence of popular opinion, joined the war on the northern German side. Soon the question arose whether they should join the North German Confederation. Bismarck did not succeed in working towards a common accession. During the separate negotiations with the southern German states, it also seemed at times that Bavaria might not join and would only be linked to northern Germany and the other southern states via a separate federation.

Finally, however, all four southern states joined on January 1, 1871, in the case of Bavaria at least retrospectively in January. On this day the new constitution of the German Confederation came into force. In this way the German Empire came into being , with essentially unchanged constitution and political system.

supporting documents

- ^ Heinrich Lutz: Foreign policy tendencies of the Habsburg monarchy from 1866 to 1870: "Re-entry in Germany" and consolidation as a European power in the alliance with France. In: Eberhard Kolb (Hrsg.): Europe before the war of 1870. Power constellation - areas of conflict - outbreak of war. R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, pp. 1-16, here pp. 1, 4/5.

- ^ Heinrich Lutz: Foreign policy tendencies of the Habsburg monarchy from 1866 to 1870: "Re-entry in Germany" and consolidation as a European power in the alliance with France. In: Eberhard Kolb (Hrsg.): Europe before the war of 1870. Power constellation - areas of conflict - outbreak of war. R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, pp. 1-16, here p. 5.

- ↑ Wilfried Radewahn: European questions and conflict zones in the calculation of French foreign policy before the war of 1870. In: Eberhard Kolb (ed.): Europe before the war of 1870. Power constellation - conflict fields - outbreak of war . R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, pp. 33-64, here pp. 35-37.

- ↑ Wilfried Radewahn: European questions and conflict zones in the calculation of French foreign policy before the war of 1870. In: Eberhard Kolb (ed.): Europe before the war of 1870. Power constellation - conflict fields - outbreak of war . R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, pp. 33-64, here pp. 37-39.

- ↑ Wilfried Radewahn: European questions and conflict zones in the calculation of French foreign policy before the war of 1870. In: Eberhard Kolb (ed.): Europe before the war of 1870. Power constellation - conflict fields - outbreak of war . R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, pp. 33-64, here pp. 40-43.

- ↑ Wilfried Radewahn: European questions and conflict zones in the calculation of French foreign policy before the war of 1870. In: Eberhard Kolb (ed.): Europe before the war of 1870. Power constellation - conflict fields - outbreak of war . R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, pp. 33-64, here pp. 43/44.

- ↑ Konrad Canis: Bismarck's Foreign Policy 1870 to 1890. Rise and Danger , Paderborn [u. a.]: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2004, p. 36.

- ↑ Konrad Canis: Bismarck's Foreign Policy 1870 to 1890. Rise and Danger , Paderborn [u. a.]: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2004, p. 29.

- ↑ Eberhard Kolb: Russia and the founding of the North German Confederation . In: Richard Dietrich (ed.): Europe and the North German Confederation . Berlin: Haude and Spenersche Verlagbuchhandlung, 1968, pp. 183–220, here pp. 196, 198/199.

- ↑ Konrad Canis: Bismarck's Foreign Policy 1870 to 1890. Rise and Danger , Paderborn [u. a.]: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2004, p. 35.

- ↑ Eberhard Kolb: Russia and the founding of the North German Confederation . In: Richard Dietrich (ed.): Europe and the North German Confederation . Berlin: Haude and Spenersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1968, pp. 183–220, here p. 210.

- ^ David Wetzel: A Duel of Nations. Germany, France and the Diplomacy of the War 1870–1871. The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison / London 2012, pp. 33/34.

- ↑ Klaus Hildebrand: No intervention. The Pax Britannica and Prussia 1865/66 - 1869/70. An investigation into English world politics in the 19th century. R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1997, pp. 383-385.

- ↑ Konrad Canis: Bismarck's Foreign Policy 1870 to 1890. Rise and Danger , Paderborn [u. a.]: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2004, pp. 29/30.

- ^ David Wetzel: A Duel of Nations. Germany, France and the Diplomacy of the War 1870–1871. The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison / London 2012, p. 36.

- ↑ Klaus Hildebrand: No intervention. The Pax Britannica and Prussia 1865/66 - 1869/70. An investigation into English world politics in the 19th century. R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1997, pp. 386/387.

- ^ David Wetzel: A Duel of Nations. Germany, France and the Diplomacy of the War 1870–1871. The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison / London 2012, pp. 34/35.

- ↑ Klaus Hildebrand: No intervention. The Pax Britannica and Prussia 1865/66 - 1869/70. An investigation into English world politics in the 19th century. R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1997, p. 335.

- ^ Heinz Günther Sasse: The establishment of the Foreign Office 1870/71. In: Foreign Office (Ed.): 100 Years of Foreign Office 1870–1970, Bonn 1970, pp. 9–22, here p. 16.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber : German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 721/722.

- ↑ Konrad Canis: Bismarck's Foreign Policy 1870 to 1890. Rise and Danger , Paderborn [u. a.]: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2004, p. 42.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 722/723.

- ^ Geoffrey Wawro: The Franco-Prussian War. The German Conquest of France in 1870–1871. Oxford University Press, Oxford [u. a.] 2003, p. 36.

- ↑ Konrad Canis: Bismarck's Foreign Policy 1870 to 1890. Rise and Danger , Paderborn [u. a.]: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2004, pp. 44/45.

- ↑ Konrad Canis: Bismarck's Foreign Policy 1870 to 1890. Rise and Danger , Paderborn [u. a.]: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2004, p. 46.

- ↑ Konrad Canis: Bismarck's Foreign Policy 1870 to 1890. Rise and Danger , Paderborn [u. a.]: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2004, p. 45.

- ^ David Wetzel: A Duel of Nations. Germany, France and the Diplomacy of the War 1870–1871. The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison / London 2012, pp. 45/46.

- ↑ Konrad Canis: Bismarck's Foreign Policy 1870 to 1890. Rise and Danger , Paderborn [u. a.]: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2004, pp. 45/46.

- ↑ Konrad Canis: Bismarck's Foreign Policy 1870 to 1890. Rise and Danger , Paderborn [u. a.]: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2004, pp. 51/52.

- ↑ Konrad Canis: Bismarck's Foreign Policy 1870 to 1890. Rise and Danger , Paderborn [u. a.]: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2004, p. 52.

- ^ David Wetzel: A Duel of Nations. Germany, France and the Diplomacy of the War 1870–1871. The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison / London 2012, pp. 35/36.

- ^ David Wetzel: A Duel of Nations. Germany, France and the Diplomacy of the War 1870–1871. The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison / London 2012, pp. 36/37.

- ^ David Wetzel: A Duel of Nations. Germany, France and the Diplomacy of the War 1870–1871. The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison / London 2012, pp. 38/39.

- ^ David Wetzel: A Duel of Nations. Germany, France and the Diplomacy of the War 1870–1871. The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison / London 2012, pp. 44, 46/47.

- ^ David Wetzel: A Duel of Nations. Germany, France and the Diplomacy of the War 1870–1871. The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison / London 2012, pp. 39/40.

- ↑ Konrad Canis: Bismarck's Foreign Policy 1870 to 1890. Rise and Danger , Paderborn [u. a.]: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2004, p. 47.

- ↑ Konrad Canis: Bismarck's Foreign Policy 1870 to 1890. Rise and Danger , Paderborn [u. a.]: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2004, p. 48.

- ^ David Wetzel: A Duel of Nations. Germany, France and the Diplomacy of the War 1870–1871. The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison / London 2012, pp. 74/75.

- ↑ Konrad Canis: Bismarck's Foreign Policy 1870 to 1890. Rise and Danger , Paderborn [u. a.]: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2004, p. 49.

- ^ Wolfgang Altgeld: The German Empire in the Italian judgment 1871–1945 . In: Klaus Hildebrandt (ed.): The German Empire in the Judgment of the Great Powers and European Neighbors (1871–1945) , R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1995, pp. 107–122, here pp. 110/111.

- ↑ John Gerow Gazley: American Opinion of German Unification, 1848-1871 . Diss. Columbia University, New York 1926, pp. 511-513.

- ↑ Konrad Canis: Bismarck's Foreign Policy 1870 to 1890. Rise and Danger , Paderborn [u. a.]: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2004, p. 48.

- ^ David Wetzel: A Duel of Nations. Germany, France and the Diplomacy of the War 1870–1871. The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison / London 2012, pp. 83-87, 100/101.