German

The ethnonym German is used in a variety of ways. In terms of ethnic Germans, this is understood to be the group of people whose relatives speak German as their mother tongue and who have specific “ German cultural characteristics”. A common origin is also often postulated; a “ völkisch ” conception of the Germans sees a common descent as the primary distinguishing feature between Germans and non-Germans. In the legal sense of the Federal Republic of Germany , all German citizens , regardless of their German or other ethnic group, form the German national people . There are close interrelationships, but also potential for conflict between the various concepts, in particular between the ethnic concept, which the Germans regarded as descendants of the German-speaking part of the population in Eastern Franconia , but was later reinterpreted nationalistically , and the provisions on legal affiliation with Germany . A feature of dealing with the German ethnicity is that the conceptions of a German nation are discussed more controversially than z. B. the national conceptions of the French , Poles or Italians .

etymology

The adjective diutisc or theodisk originally meant something like “belonging to the people” or “speaking the language of the people” and has been used since the late Carolingian period to denote the non-Romance-speaking population of the Franconian Empire , but also the Anglo-Saxons . It was created to distinguish it from the Latin of the priests as well as the walhisk , the name for the novels from which the word Welsche originated.

The first evidence for the term is a passage from the Gothic translation of the Bible by Wulfila around 360. He denotes the non-Jews, the pagan peoples, with the adjective thiudisko .

The language of Germanic or old German tribes was first referred to as diutisc or theodisk in a letter from the papal nuncio Gregory of Ostia to Pope Hadrian I about two synods that had taken place in England in 786 . The letter stated literally that the council resolutions tam latine quam theodisce (“in Latin as well as in the vernacular”) were communicated “so that everyone could understand” (quo omnes intellegere potuissent) . In its ( old high ) German form diutsch or tiutsch it can first be documented in the writings Notkers des Deutschen .

It was not until the 10th century that the use of the word diutisc became common to the inhabitants of Eastern Franconia , of which the largest share in terms of area today belongs to Germany.

Grammatical and typological features

In contrast to all other national names in Indo-European languages, the word for people of German ethnicity is a substantiated adjective. For most of the other names, the name of the country is the basis of a derivation of the personal name (cf. England - English). This reflects that Germans have not founded a joint political association whose name could form the basis for the designation of nationals. The nationality designation “German” has therefore retained the blurring of the derivation from the language designation. Austrians and German-speaking Swiss would also be “Germans” in the original linguistically derived sense (German speakers), but no longer in the national sense, whereby there can be overlaps, especially when it comes to historical circumstances (for example Austria as the leading power of the German Confederation until 1866).

Due to the declination rules for adjectives , the nationality designation takes on an unusual variety of forms. Even many native speakers are unsure about the correct formation of forms: does it mean “all Germans” or “all Germans”, “we Germans” or “we Germans”? The so-called strong or weak forms are both acceptable according to the Duden. Because of the adjectival form, there is also no feminine derivation (cf. the German - the Italian or in the plural: the German women - the Italian women ).

In terms of language typology , the expression German in the original sense of "German-speaking" is a specialty, insofar as it is an asymmetrical pluricentric language with several standard varieties. “German is considered a prototypical example of a language that is supported by a pluricentric language culture” (Ludwig Eichinger). This complexity and heterogeneity is also historical and the cause of many ambiguities and misunderstandings, which are expressed, for example, in the question of whether Swiss German speak and write German or Swiss German or Swiss Standard German and to what extent the spelling rules of Federal German extend.

Germans as an ethnic group

From around the beginning of the 19th century, since the wars of freedom against Napoleonic rule , the idea of an ethnic and cultural unity among Germans has been the most important basis for German nation concepts. Since there was no German nation- state, the concept of the national community was not constituted through a state, but through ideas of cultural (especially linguistic) identity and common ancestry. This has shaped the German understanding of nationality to the present day and is expressed, for example, in the provisions on German citizenship . According to Friedrich Meinecke , such a nation is distinguished as a cultural nation from state nations on the other side, according to which the German nation is one of the first primarily culturally and ethnically conceived nations alongside the Italian one.

Ethnogenesis

The territorial-political conception of the ethnic Germans emerged at the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century. In contrast, the term “German” for people who speak German as their mother tongue has existed for much longer, although there have been various changes in meaning in the development of this adjective .

Origins

The first written records about the inhabitants of today's Germany were written by Caesar around the turn of times and concern western Germans who were settled east of the Rhine and formed into large tribes (i.e. Saxons , Thuringians , Franks , Alemanni and Baiern ) during the migration of peoples . In what is now western, central and southern Germany, before the Germanic conquest at the turn of the times, mainly Celts lived who were mentioned by Herodotus with their city of Pyrene . These were apparently assimilated or replaced relatively quickly in the areas up to the borders of the Roman Empire . Romanized Celts ( Gallo-Romans ) lived south-west of the Limes until late antiquity , but they are likely to have been increasingly interspersed with Germanic federates, especially in the border areas. After the fall of the Roman Empire , the majority of these Gallo-Romans apparently adopted the Germanic languages relatively soon , although some Romance language islands , such as Moselle Romance , survived into the high Middle Ages in the area of today's Federal Republic of Germany. Celts and Gallo-Romans in particular contributed to the emergence of the Alemanni and Bavarians. From the 7th century, Slavs increasingly immigrated to the eastern areas of former and present Germany , assimilated and thus also became an important group of ancestors of the Germans.

By conquering the Alemannic, Bavarian, Rhenish Franconian and Thuringian regions, the Salian Franks united these great tribes in a political entity. The Alemanni were partly subdued in 496 and finally in 536, the Thuringians in 531 and the Bavarians in 536. The Frisians of the north German marshland and the Saxons, on the other hand, remained largely independent for the time being and were closer to the English than to the Upper Germans for a long time. After the emigration of the Anglo-Saxons, the mainland Saxons and the sub-tribes they subjugated formed a special people with their own state institutions. Since the Merovingian era , the Saxons have been loosely dependent on the Franconian Empire, but this is usually limited to paying tribute and providing troops. It was not until its political and religious compulsory integration into the Frankish Empire of Charlemagne in 797 that it became part of the later German state association . It took even longer before Frisians living on the German North Sea coast were ready to see themselves as Germans. In 1463 there was still talk of “Freschen boden or grunt” as opposed to “Duitschen grunt”. Until well into modern times , Frisians only began to live inland, the border of their settlement areas "Germany".

The origin of Germany is ultimately based on the systematic will to conquer and the organizational skills of the Merovingian kings and Charlemagne as well as the divergence of the East Franconian and West Franconian empires . The term German , as a self-designation for the Germanic-speaking inhabitants in the old German Empire , on the other hand, only appeared in the high Middle Ages.

Middle Ages and early modern times

In the course of the high medieval settlement movement to the east , large parts of the Western Slavs , who had immigrated from the late 6th and 7th centuries to the areas largely cleared by the Germanic peoples during the migration (roughly identical to the new federal states east of the Elbe-Saale line), went , eastern Holstein, Wendland in Lower Saxony and parts of Upper Franconia and eastern Austria - see Germania Slavica ) in the German-speaking population. The last non-assimilated groups of these Slavs are the now bilingual Sorbs in Lusatia (max. 60,000) and to a certain extent also the Carinthian Slovenes in Austria, which - unlike the Sorbs - represent a direct continuation of the Slovene settlement area in today's Slovenia .

In the Holy Roman Empire , which had the addition of “German Nation” since around 1550, increasingly independent territories developed below the Empire, whose subjects also developed a corresponding identity related to the small state: Thus one fought in wars for one's prince the army of the neighboring prince, and the type of religious practice in the age of the Reformation was not determined by an all-German authority (unlike in England or France , for example ), but by the respective territorial rulers. Therefore, a German identity was naturally more limited to the linguistic and cultural area. However, this became more and more important over time, but above all due to the increased participation of the population in the written culture . Ulrich von Hutten and Martin Luther were therefore able to count on broad support with their struggle against “Welsche” church rule. In 1520 Luther addressed the Christian nobility of the “German nation” in one of his main writings .

The Baroque poets also stood up for the German language and against influences from other languages, even if Frederick the Great , for example, still preferred French culture, which gave German culture important impulses in the early modern era (model Louis XIV, Huguenots ). German culture also received important stimuli from immigrants , including the Huguenots (among whose descendants Theodor Fontane can be found). The Jewish minority also played a decisive role in German intellectual life ( Moses Mendelssohn , Heinrich Heine and others). Since Germany was not a central state like England, the Netherlands or France, the formation of a German nation took place with a delay and, to a significant extent, only took place after the conflict with the French Empire under Napoleon Bonaparte .

In the course of time, other population groups immigrated to the German-speaking area, for example in the second half of the 19th century many Poles and Masurians into the Ruhr area , and assimilated over time. On the other hand, German population groups (from Switzerland , the German Empire, etc.) also emigrated to foreign-language or overseas areas, founded their own colonies there or were assimilated by the local population.

The modern German nation

Until the end of the 18th century there was no pronounced German national consciousness. A change only brought about the national movements in the first half and the middle of the 19th century, which received a great boost after the victorious wars of liberation against Napoleonic rule. They questioned the legitimacy of the ruling dynasties and combined national unity with the demand for political participation by the people and economic liberalization.

The ethnicity , which should be the basis of the state instead of the dynasty, was mainly derived from the mother tongue in Central and Eastern Europe , as there were no nation states as objects of identification. The German national movement failed, however, after the March Revolution of 1848. It was not until 1871 that the first unified German nation-state was established with the establishment of the Reich . Its inhabitants were referred to as " Reichsdeutsche ". Other Germans mostly had their settlement areas in multiethnic states and called themselves, for example, Banat Swabians or Sudeten Germans , etc. For them, the collective term " Volksdeutsche " was mainly used in connection with National Socialism . In the full course of the DC circuit of the countries to Nazi unitary state carried out by the Law on the reorganization of the empire of 30 January 1934 Regulation of 5 February 1934, the first-time and still valid anchor of German nationality in the civil registers.

Talking by ethnic Germans has often had an anti-Semitic tendency since the beginning of the emancipation of the Jews . Although many German Jews felt they belonged to a German cultural nation and were German citizens, an understanding of a German nation with the exclusion of Jews established itself. As a reaction to the Holocaust , the question of whether they are Jewish Germans or not more Jews in Germany has been discussed among Jews living in Germany since the end of the Second World War .

According to several studies, the majority of Germans themselves say that the most decisive criterion for being German is the use of the German language . According to a study by the Berlin Institute for Empirical Integration and Migration Research, "the vast majority of the population no longer defines being German solely by origin, but by other criteria." According to this, 96.8% of the respondents were of the opinion that whoever uses German is German. Furthermore, 78.9% said that they require a German passport to be German. 37% said that someone must have German ancestors in order to be German.

Ethnic concept

Parallel to and partly interwoven with the ethnic concept, a völkisch understanding of Germanness developed from the beginning of the 19th century . Building on Novalis ' writings , Friedrich Schlegel developed the idea of a “true” nation around 1801, which would form a family-like network and thus be based on common bloodlines , i.e. common ancestry , of all nation members. Contrary to any historical knowledge, Schlegel assumed that a common language testifies to a common ancestry. Many observers still see the ethnic element as the central defining characteristic of today's German nation. The speech of Germanness carried off its historic triumph with the revolution of March 1848 ; there, however, it was understood as a plea for the unification of the empire , which then took place in 1870/71.

Newer approaches in sociology and psychology

Assimilation hypothesis and ancestry hypothesis

On the basis of the question of whether someone can become ethnically German , the supporters of the assimilation hypothesis can be distinguished from those of the ancestry hypothesis. The assimilation hypothesis states that adaptation to central cultural characteristics is important. Above all, these are the command of the German language, sometimes not belonging to Islam , the length of living in Germany and a German spouse. The parentage hypothesis, on the other hand, claims that you cannot learn to “be German”: you are therefore only “German” if your parents are German. Even Bassam Tibi , a German political scientist of Syrian origin, is to explicitly state: "An ethnic identity can not be acquired." According to a study by Tatjana Radchenko and Débora Maehler from 2010 is only true to a survey of 123 migrants and not interviewed indigenous German of Statement on: "You can never really become German."

According to a study by the Humboldt University of Berlin entitled “Germany postmigrant”, for which more than 8,200 people were surveyed, in 2014 37 percent were of the opinion that German ancestors are important in order to be German or German. Over 40 percent of the population are of the opinion that you have to speak German without an accent. 38 percent of the population say that someone who wears a headscarf cannot be German.

The thesis that supporters of the assimilation hypothesis also have problems seeing ethnic Germans in Muslims is confirmed by the “Society of Muslim Social Scientists and Humanities Scientists”: They have the impression that “any adherence to genuinely Islamic positions that is not that of Western- The framework for religiosity, integration criteria and German identity set on the occidental side can only be interpreted by the majority society as a dangerous deviation from the social consensus. "

In April 2016, the sociologist and journalist Christian Jakob claimed that “the time when 'only those of German descent can be German'” was “over”.

New Germans

The term “New Germans” is a post-modern construct to understand the identity-building processes of German nationals with a migration background as inclusion processes in principle. In the research project “ Hybrid European-Muslim Identity Models” (HEYMAT), which is headed by Naika Foroutan and Isabel Schäfer and based at the Humboldt University in Berlin, it is used for people with a Muslim migration background.

In a loss and gain. In April 2015, Felix Grigat examined the results of current studies on immigration entitled “Who belongs to the German we?”. According to the above-mentioned study by the Humboldt University, 81 percent of German nationals with a migration background said they love Germany in 2014, and 77 percent feel German as a result. Almost every second German with a migration background (47 percent) is important to be seen as German - just as much as among Germans without a migration background (47 percent).

Germanophilia

Germanophilia (from Latin Germani, “ Germanen ”, and Greek φιλία (philia), “friendship”) denotes a general affinity to German culture , history or the German people and thus the counterpart of Germanophobia . An equation of "Teutons" and "Germans" was first made in the 16th century by Johannes Turmayr, known as Aventinus. In German , however, the term mainly exists as a literal translation of the term germanophilia , which is more commonly used in English , and is used for various cultural-historical, social and literary phenomena.

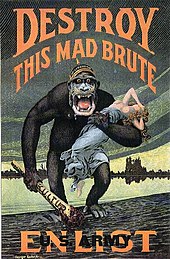

Hostility towards Germans

Anti- German hostility , Germanophobia or German hatred (French Germanophobie , English Germanophobia ) was a widespread phenomenon in the time of the imperialist conflicts between the great powers around the turn of the century (19th / 20th century) and especially during and during the persecution of Nazi violent crimes. The term was used after the Second World War a. a. used by right-wing extremist groups for historical revisionist propaganda.

The term anti- German hatred was occasionally used to describe bullying of ethnic German students by classmates with a migration background . The word experienced an intensified debate from 2009 in connection with the bullying of Muslim schoolchildren observed by Berlin teachers and academics . In 2017 the Criminological Research Institute Lower Saxony e. V. assumes that there is an issue of “hostility towards Germans” and operationalized statements to which the young people interviewed agreed, as well as the behavior they practice, which it assessed as an expression of hostility towards Germans.

The political term in Germany

Domestic law

De jure all persons are Germans who

- have German citizenship ( § 1 StAG) or

- as refugees or displaced persons of German ethnicity found admission on the territory of the German Reich within the borders of December 31, 1937 (→ status German ; Art. 116 para. 1 GG ).

The German law recognizes different terms of the "German". In the parlance of the Basic Law , according to Art. 116, not only are German citizens “Germans”, but also those who can prove their descent from German ancestors under certain circumstances (status Germans). This is important, for example, when someone in Germany asserts a civil right for himself, in particular the right to permanent residence in Germany ( freedom of movement within the meaning of Art. 11 GG ), the right to free choice of profession (Art. 12 GG) or that Right to pension payments under the Foreign Pension Act . Section 6 of the Federal Expellees Act (BVFG) defines a member of the German people as someone who "has committed himself to the German nationality in his home country, provided this commitment is confirmed by certain characteristics such as origin, language, upbringing, culture."

Special cases represent people who, as German citizens, maintained their place of residence east of the Oder-Neisse line in 1945 , and people who, according to Art. 116 (2) GG, are entitled to have their illegal expatriation for political or racial reasons during the Time of National Socialism is reversed. The descendants of both groups have a legal right to confirmation of German citizenship if they submit a corresponding application. These are mainly citizens of the Republic of Poland and Israel .

International treaties

After the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe and the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact , the Federal Republic of Germany concluded treaties through which the contracting parties undertook to protect the German minority in their national territories. These are the following contracts :

- Treaty with Poland of June 17, 1991

- Treaty with the Czech and Slovak Republics dated February 27, 1992

- Treaty with Hungary dated February 6, 1992

- Treaty with Romania of April 21, 1992.

The term “ national minority ” is to be understood in the sense of the “Framework Convention of the Council of Europe for the Protection of National Minorities”, which Germany signed on May 11, 1995. Article 3 of this convention states: “Any person belonging to a national minority has the right to choose freely whether or not to be treated as such; This decision or the exercise of the rights associated with this decision must not result in any disadvantages. "A Polish citizen of German descent has the right, for example, to decide for himself whether he would like to be classified and treated as a" German "or not, and" German language examinations ”do not take place for members of the national minority of Germans where they are recognized. However, the latter regulation does not apply to persons who are recognized as ethnic German repatriates and who wish to become German citizens .

A corresponding regulation was already agreed in the German-Danish agreement of March 29, 1955. There the Danish government declares: "The commitment to German nationality and German culture is free and may not be disputed or verified ex officio."

The Federal Republic of Germany supports German minorities in the countries with which they did the above mentioned in the 1990s. Has concluded contracts. However, only intermediary organizations are benefited. There is no direct support for individuals who belong to the German minority. Members of German minorities do not have any legal claims against the German state that go beyond the guarantees of Art. 116 GG (→ Bleibehilfen ).

Conceptual boundaries

People with German ancestry are called German descent designated (eg. As Americans of German descent) when they are generally all or part of German descent. German descent differ from ethnic Germans (ethnic Germans) in that they do not necessarily have to have preserved their German heritage, the German language and the German customs and have not only preserved in general or in part. When determining a popular ancestry from Central Europe, the number of Germans is significantly higher than when defining nationality or mother tongue and is given as up to 150 million people - including the approximately 43 million people living in the United States of Live America , attribute their main origins to German immigrants and describe themselves as German-Americans .

Persons of German nationality who have moved abroad are referred to as Germans abroad .

Deutschtum is a rather rare term for a German being, a culture of Germans, also outside of Germany (cf. Volkstum ). Thus named in 1908 General German School Association in Unit for German abroad (today at Association of German cultural relations abroad ). In this context, Deutschtümelei applies as an intrusive emphasis on something - of whatever kind - "typically German".

In connection with the terms Deutschtum and Deutschtümelei or exaggerated emphasis on the German essence , reference should be made to the origin and original meaning of the word " German " highlighted above . It was initially a delimiting term for "Celtic inhabitants of Western European areas" and - derived from this - has also assumed a historical meaning. From this point of view, the term German is best understood and judged correctly from the contrast to welsch . Seen in this way, the term “German” is a term of Germanic linguistic origin, but was initially mainly used in the Latinized form theodisca lingua as the official name of the Germanic (old Franconian) language in the empire of Charlemagne . The designation Germania is also a Roman term and not a name that the so-called peoples have given themselves. Historically, the situation of the Great Migration and the Romanization of Germania, which the Roman Empire was politically striving for, played a decisive role. The negative evaluation and meaning of the term Deutschtümelei depends on a purely demarcating attitude between these cultural and linguistic influences. The moment of demarcation and exclusion is not only evident in the pair of terms “welsch” and “German”, but also in the term “ barbarians ”. In antiquity, this was a collective term originally for all peoples who were remote from Greek and later also from Roman culture.

Geographical distribution

The majority of Germans now live in Germany, where they form the titular nation . In addition, there are other groups, especially in Europe , who consider themselves ethnically German.

Germans and non-Germans in Germany

Most of the people who are referred to as “Germans” now live in Germany , the German nation-state. After the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic , only these two states still had the word “German” or “Germany” in their state name. Art. 116 of the Basic Law includes with the term "German" more people than those with German citizenship, namely also the so-called status Germans , whose number is now assumed to be very low. When “Germans” are mentioned after German reunification , they usually mean people with German citizenship.

Not all residents of Germany are German citizens and not all German citizens are ethnic Germans. The non-existing German citizenship of a person living in the Federal Republic may only be legally asserted to defend against claims if the person concerned invokes a civil right. Otherwise, Article 3 of the Basic Law prohibits disadvantaging or preferring people on the basis of their descent and origin. In the history of the Federal Republic of Germany, a purely ethnic definition of Germans has been increasingly called into question, initially due to increasing labor migration since the 1950s. After reunification and the collapse of the Soviet Union , as the number of status Germans decreased , so did the need for a definition of Germans that went beyond the national borders of Germany , so that in the reform of German citizenship law in 2000 for the first time since the beginning of the 20th century, elements of the Birthplace principle ( ius soli ) found entry.

The rights of recognized national minorities in Germany are protected by law. This means that you decide for yourself whether you want to be treated in a certain situation as a German (by virtue of citizenship) or as a member of an ethnic or national minority (with a documented right, e.g. to the maintenance of customs or your own schools).

The relationship of the Frisians in Germany to the question of their "(non) German identity" is complicated:

“The Frisians in East Frisia are united by a feeling of shared history and culture, which is expressed in a regional identity. They do not consider themselves a national minority. The Sater Frisians consider themselves a Sater Frisian language group. The largest group of the organisationally united North Frisians - the North Frisian Association - does not see itself as a national minority either, but as a group with its own language, history and culture within Germany. The second supraregional organization, the Friisk Foriining (formerly 'Foriining for nationale friiske') sees the Frisians as an independent people and regards themselves as a national minority in Germany. Today both groups agreed on the compromise designation 'Frisian ethnic group' and are also referred to in the constitution of Schleswig-Holstein .

According to the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, the status of the Frisian ethnic group is equated with that of a national minority. This is welcomed by all Frisian associations and organizations. "

Incidentally, many sociologists do not think it makes sense to fix the origins of people with a migration background in Germany (as is done in some Eastern European countries with the help of nationality entries): "The dynamic of modern society [is] considerably more inclusive [...] than that political semantics in Germany over the past 40 years. It is known from international migration research that migrants with permanent residence status differ less and less from the autochthonous population, which is not to be understood in the sense of cultural assimilation , but in the sense that the institutions of law and the market, education and perhaps also become more indifferent to politics for origins. "

Sociological concepts of hybridity and diversity management call into question the idea that people have to be either Germans or non-Germans and "profess" one of the two. Rather, German citizens and people who have not been German citizens who have lived in Germany for a long time are often “other Germans”. This is particularly true of Muslim permanent residents of Germany.

German speakers in the closed German-speaking area outside of Germany

Citizens of Austria , Switzerland , Liechtenstein , Luxembourg and other German-speaking regions are legally not Germans, even if they speak German as their mother tongue , unless they also have German citizenship.

Austria

Parts of the 18th and 19th centuries were characterized by the escalation of the conflict between Prussians and Austrians over supremacy within the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, which resulted in German dualism . 1806 put the last Roman Emperor German , Franz II., His crown down because numerous German princes from the French Emperor Napoleon I created Confederation of the Rhine had joined. The Austrian Empire was established in 1804 when Emperor Franz II was crowned Emperor of Austria as Franz I. After Austria joined the alliance of Prussia and the Russian Empire against Napoléon in the summer of 1813 and inflicted a severe military defeat on the French emperor in the Battle of Leipzig , the foundation stone was laid for the German Confederation founded in 1815 , which in turn linked Prussia and Austria. When the establishment of a German nation-state seemed possible in the revolution of 1848 , there was heated argument about whether a Greater German solution could be found together with Austria . The Habsburg Empire also encompassed numerous areas in which Germans were only a minority, such as Bohemia and Hungary , the inclusion of which would have been in conflict with a nation-state solution. The German question was resolved in 1867 or 1870/71 by the fact that the Kingdom of Prussia first achieved a military victory over Austria , founded the North German Confederation and then implemented the solution of a largely Prussian German Empire without Austria (→ Small German Solution ). Nonetheless, alliance political connections continued to exist, as were the usual cultural connections that are common between friendly neighboring states.

After the disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy , the Republic of Austria came into being in 1918 (briefly referred to as German Austria ). There was a lot of skepticism as to the extent to which this “remnant” or “rump state” - deprived of the Hungarian agricultural and Bohemian industrial areas - was viable on its own. A merger with the Germany of the Weimar Republic was made impossible by the Treaty of Saint-Germain ( connection ban ). With its ratification in 1919, the name "German Austria" was also prohibited and changed to "Republic of Austria ".

During the time of the Austro-Fascist corporate state (1933 to 1938) - which began with the elimination of parliament and the elimination of democratic structures by Federal Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss - it was the official standpoint of those in power that Austria was the "second" - and because of the Catholic foundation - To be regarded as a “better German state”. A national awareness of one's own was only rudimentary; one felt like an Austrian, but was only vaguely demarcated from the Germans. When Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg came under increasing pressure from Germany and called a referendum on whether Austria should become part of Germany, and even intended to rely on the support of the social democrats who had been persecuted to date, the German leadership ultimately demanded that the vote be canceled. Finally, the German Wehrmacht invaded Austria. The “Anschluss” of Austria on March 13, 1938 was welcomed by numerous people, while others had to flee or were arrested. Leading representatives of the Austrian Social Democrats and the Fatherland Front , including Schuschnigg, were sent to concentration camps . The referendum originally initiated by Schuschnigg finally took place under pseudo-democratic circumstances - without voting secrecy - and led to the approval sought by the new authorities. The name of Austria was of the terms of the now Reichsgaue reshaped states repaid (as was Upper and Lower Austria to Upper and Lower Danube ). The events that followed, the Second World War and the National Socialist dictatorship , then led to an increased desire to return to an Austrian nation-state. Many Austrians were active as resistance fighters against the National Socialist regime. B. Carl Szokoll - or had to pay for their lives because of their oppositional stance - such as Franz Jägerstätter , who had already refused to integrate Austria into the neighboring country in 1938.

Immediately after the liberation of Austria and the reestablishment of the Republic of Austria, on July 10, 1945, the Austrian Citizenship Transition Act ( StGBl. No. 59/1945 ) revoked the collective naturalization of Austrian citizens in the course of the annexation of Austria to Germany . Supported by the successful history of the Second Republic, there was also a clear demarcation from the Germans. In addition to the experiences with National Socialism, the fact that Austria, as the “first victim of National Socialism”, hoped for better peace conditions against the occupying powers also contributed to this. Major Austrian politicians suffered under the National Socialist regime - such as Leopold Figl and Adolf Schärf - or had to emigrate (such as Bruno Kreisky ). Today, Austrians almost unanimously (with the exception of German national citizens who, according to empirical studies, make up less than five percent) do not describe themselves as “Germans” despite the common language - where differences in grammar, style and especially the dialects are, however; its own Austrian identity has long since become unmistakable. In the Republic of Austria, a distinction is made between German, Slovenian, Romansh, Slovak, Hungarian and Croatian speaking Austrians, and the official minority languages are regulated accordingly .

In Austria there is a German national wing, especially in the “ Third Camp ” , whose supporters see themselves as ethnic Germans .

Switzerland

The (Upper) German-speaking Swiss have in fact been politically separated from the Inner German or the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation since the Swabian War and formally since the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 . They call themselves " German Swiss " - especially as a demarcation from the French (speaking) Switzerland, Romandie - and describe their dialects to collectively as Swiss German , but they do not consider themselves at least since the late 19th century more than the German people belong: "Germans themselves were only the Reich Germans ." This attitude was strengthened by the Wilhelmine era and, above all, by the rule of National Socialism in Germany.

Liechtenstein

The Principality of Liechtenstein is the only country in the German-speaking area to exclusively use German as the official and school language.

After the end of the Holy Roman Empire, Liechtenstein became independent in 1806 and was a member of the German Confederation in the 19th century. From 1852 to 1919, Liechtenstein was economically linked to Austria by a customs treaty. After the Habsburg monarchy was dissolved, it increasingly leaned against Switzerland (Customs Treaty 1923). Using the example of the national anthem, one can see that during the First World War, the Germanness of Liechtenstein was questioned, but could also be emphatically defended by contemporaries. The anthem Oben am Deutschen Rhein , composed in the middle of the 19th century, was already widespread around 1895 and was the official national anthem from 1920 at the latest . The designation of the Rhine as German and even clear references to Germany ( “This dear homeland in the German fatherland” ) evidently did not cause any offense in the 19th century. As late as 1916, a regional poem could contain the German Rhine and the poet could call himself “a German”. Almost at the same time, however, there was also an attempt by a poet to remove German references from the hymn with the text “Oben am Junge Rhein” - this encountered resistance. From the 1930s, sometimes violent disputes between German or even National Socialist-minded Liechtensteiners and Liechtenstein national patriots over the text of the anthem have come down to us. Loyal groups used an "adjusted" text to differentiate themselves from the National Socialists and the German Reich. Despite renewed attempts at reform shortly after the end of the war, it was not until 1963 that the Landtag declared a slightly modified text without the term German to be the state anthem.

Belgium

German is one of the three official languages of Belgium and is spoken as a mother tongue in the east of the country, mainly in the cantons of Eupen and Sankt Vith . German enjoys its official status in the German-speaking Community , which consists of the parts of New Belgium that belonged to Germany (or the Rhine Province ) until 1920 , with the exception of the municipalities of Malmedy and Weismes ( Canton Malmedy ), where the majority already existed before it was incorporated into Belgium French was spoken. In addition, there are places in Belgium where German was spoken before 1920 (old Belgium). They are outside the German-speaking community of Belgium and the only official and teaching language is French. These are two separate regions: Old Belgium South (the Areler Land ) in the extreme south-east of the country; it includes the city of Arel and a few surrounding villages, as well as Alt-Belgium-Nord (the area around the places Bleiberg - Welkenraedt - Baelen , all three are west or northwest of Eupen).

Luxembourg

German is the official language alongside Luxembourgish and French and is one of the three administrative and judicial languages of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg .

South Tyrol (Italy)

South Tyrol had to be ceded by Austria to Italy in 1919 through the Treaty of Saint-Germain . Fascist Italy from 1922 onwards suppressed the non-Italian population, their language and culture and pursued a rigorous policy of Italianization . The "annexation" of Austria to the German Reich resulted in an agreement between Hitler and Mussolini . In October 1939, the German residents (at that time 80% of the population) and the Ladins had to choose between staying in their homeland when giving up their German or Ladin first and last names, their language and culture ( Dableiber ) or they opted , i.e. H. Emigration and settlement in Germany or the areas occupied by German during World War II as well as acceptance of German citizenship ( optanten ). Although 86% of those eligible to vote - only men were eligible to vote and, if necessary, voted for their families - for resettlement, only 72,000 of these actually emigrated. In 1946, South Tyrol was formally granted autonomy , which, however, was not fully implemented until the 2nd Statute of Autonomy in 1972. Today, after a low point in the 1950s, around 69% of the population are Germans again.

In the Italian provinces of Trentino and Vicenza south of the Alps there are still around 1000 Cimbri , speakers of the southernmost German dialect, Cimbrian .

Denmark

For Denmark see German minority in Denmark .

France

German minorities outside the closed German-speaking area

Individuals who feel they belong to German culture but come from German settlement areas outside of Germany are sometimes referred to as ethnic Germans - for example by the associations of expellees . Spätaussiedler belonging to this group ( § 4 BVFG), who left the successor states of the Soviet Union after December 31, 1992 in order to settle in Germany within six months, have a limited right to be granted German citizenship . If they have not met this claim, they are not legally considered to be Germans despite their German ethnicity.

German-speaking minorities live in Poland (→ German minority in Poland , especially in Upper Silesia ), the Czech Republic , Slovakia , Hungary ( Hungarian-Germans ) and Romania ( Romanian- Germans ), and outside Europe in Israel , Namibia , Brazil (→ German-Brazilian ), Chile (→ Germans in Chile ) and in the USA (→ German-American ). There is also a smaller group of German immigrants in Turkey called Bosporus Germans .

Assimilation took place to varying degrees in the emigrant groups: many immigrants have adapted completely to the culture of the host country and, in some cases, have also changed their names accordingly (e.g. Schmidt in Smith), others consider, in a more or less intensive form, cultural and folkloric traditions. The Second World War in particular contributed to the fact that many Germans distanced themselves from the German mother country. In contrast, the Amish , the old-order Mennonites and the Hutterites in the United States and Canada , as well as conservative old colonial Mennonites in Latin America , remained tied to tradition . These groups comprise more than half a million people.

There were different waves of emigration to the USA. In the 18th century, many Germans settled in New York and Pennsylvania , including in particular Germantown and the area around Lancaster (Pennsylvania) . In the mid-19th century, the Midwest was a particularly popular destination. Among the cities, Cincinnati , St. Louis , Chicago and Milwaukee were the preferred locations, but many rural areas from Ohio to Illinois to North Dakota were also preferred by the more agriculturally interested emigrants.

The part already 800 years ago ( Cimbrians , Saxons , Zipser , a Baltic German ) or much later ( Danube Swabians , Bukovina German , Volga German , Black Sea German ) for East-Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkan expatriate Germans had their cultural identity partly preserved, but for the most Partly mixed with the respective local population. After the end of the Second World War, almost all of them were deported, expelled , fled or emigrated in the following period. Only in Poland, Hungary, Russia ( Russian-Germans ), Kazakhstan , Kyrgyzstan , in rapidly decreasing numbers in Romania and in small numbers also in the Czech Republic and the republics of the former Yugoslavia ( Yugoslav Germans ) are there still minorities (according to their own understanding) , some of which are descended from medieval or modern German emigrants .

The German communities that emigrated around the Second World War developed their identity mainly in Brazil (area around Blumenau and around Novo Hamburgo in Rio Grande do Sul ), Argentina ( Misiones , Crespo , Coronel Suárez , Bariloche , Villa General Belgrano ), Chile (for example Areas around Valdivia , Osorno , Puerto Varas and Puerto Montt ), Paraguay (including Mennonites in the Gran Chaco and Swabia in the Itapúa department ) and Namibia. There are also German-language newspapers (e.g. the Allgemeine Zeitung in Namibia), schools and a more or less lively cultural life.

See also

- Anti-German

- German in other languages (list of names of the German language in other languages)

- Herb (ethnophaulism) ("Krauts")

literature

- What is German? Questions about the self-image of a brooding nation . Catalog volume for the exhibition of the same name by the Germanisches Nationalmuseum Nürnberg, Verlag des Germanisches Nationalmuseums, 2006.

- Heinrich Beck, Dieter Geuenich, Heiko Steuer , Dietrich Hakelberg (eds.): On the history of the equation "Germanic - German". Language and names, history and institutions , supplementary volumes to the Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, Bd. 34. Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-11-017536-3 .

( Contents of the volume ; review by Gregor Hufenreuter in: Historische Literatur , review magazine by H-Soz-u-Kult. Steiner, Stuttgart July 22, 2004, ISSN 1611-9509 .) - Michael Gehler / Thomas Fischer (eds.): Door to door. Comparative aspects to Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Austria and Germany . Vienna 2014.

- Michael Gehler / Hinnerk Meyer (eds.): Germany, the West and European parliamentarism. Hildesheim 2012.

- Dieter Geuenich : Germanico = Tedesco? Come gli antichi Germani sono diventati gli antenati dei Tedeschi di oggi. In: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries 86 (2006), pp. 41–63 ( online ) (German: 'Germanic = German? How the ancient Germanic people became the ancestors of today's Germans').

- Holm Arno Leonhardt: German organizational talent. On the economic historical roots of a national stereotype. In: Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie 59 (2015), no. 1, pp. 51–64.

- Herfried Münkler / Marina Münkler : The new Germans: A country ahead of its future. Rowohlt, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-87134-167-0 .

- Dominik Nagl: Borderline cases - citizenship, racism and national identity under German colonial rule . Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-631-56458-5 . ( Table of contents )

- Hermann Weisert: How long have you been talking about Germans? In: Blätter für deutsche Landesgeschichte , Vol. 133, 1997, pp. 131–168.

- Peter Watson : The German Genius. A spiritual and cultural history from Bach to Benedict XVI . 3. Edition. C. Bertelsmann, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-570-01085-3 (English: The German Genius . Translated by Yvonne Badal).

Web links

- Judgment of the Federal Constitutional Court on the “Confession of German Volkstum” from December 16, 1981

- Judgment of the Federal Administrative Court on the "Confession of German Volkstum" of November 13, 2003 (PDF; 94 kB)

- Page no longer available , search in web archives: judgment of the Federal Administrative Court on the meaning of nationality entries from May 3, 2007 (PDF; 41 kB)

- Wolfgang Kaschuba: German We-Images after 1945: Ethnic Patriotism as Collective Memory? (PDF; 180 kB)

- Georg Hansen: The ethnicization of German citizenship law and its suitability in the EU (PDF; 187 kB)

- Matthias Kulinna: Ethnomarketing in Germany. The construction of ethnicity by marketing actors. Frankfurt 2007, dissertation at Faculty 11 Geosciences / Geography at Goethe University Frankfurt am Main , 278 pages (PDF; 2.7 MB)

- Berlin Institute for Empirical Integration and Migration Research at the Humboldt University of Berlin (BIM): Germany postmigrant I - society, religion, identity. First results (2014) and BIM: Germany postmigrant II - attitudes of adolescents and young adults towards society, religion and identity (2015)

Individual evidence

- ↑ The “German cultural characteristics” do not follow a general definition. Even people whose last name is clearly Scandinavian (e.g. Peter Harry Carstensen ), Romansh (e.g. Jürgen Dubois ) or Slavic (e.g. Willy Millowitsch ) are or were considered to be German, without it being possible to determine precisely From what point in time and through what cultural characteristics the families in question “switched” from non-German ethnic groups to German ethnic groups.

- ↑ Cf. Theodor Schweisfurth , Völkerrecht , Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2006, chap. 1 § 3.I Rn. 25 .

- ↑ þiudisko

- ↑ Hagen Schulze: Little German History , dtv, 7th edition 2005, p. 19.

- ↑ Onion fish: We Germans or we Germans? In: Spiegel Online . March 2, 2005, accessed January 26, 2016 .

- ↑ Grammar in Questions and Answers. In: hypermedia.ids-mannheim.de. Retrieved January 26, 2016 .

- ↑ Ludwig M. Eichinger: OPUS 4 - The German considered as a pluricentric language. Institute for German Language (IDS), August 6, 2015, accessed on February 8, 2016 .

- ↑ Gerhard Stickel (Ed.): Varieties of German: Regional and Colloquial Languages (= Institute for German Language Yearbook 1996). de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1997.

- ↑ Peter Wiesinger: 'Nation' and 'Language' in Austria. In: Andreas Gardt (ed.): Nation and Language. The discussion of their relationship in past and present , de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2000, pp. 525–562.

- ^ Helmut Spiekermann: Regional standardization, national destandardization. In: Ludwig M. Eichinger / Werner Kallmeyer (eds.): Standard Variation. How much variation can the German language tolerate? (= Institute for German Language Yearbook 2004), de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, pp. 100–125.

- ↑ See Peter Glanninger, Racism and Right-Wing Extremism. Racist argumentation patterns and their historical lines of development. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-631-57501-7 , p. 148.

- ↑ See Erwin Allesch, in: Dieter C. Umbach / Thomas Clemens (eds.), Basic Law. Staff commentary , Vol. I, 2002, Art. 16, Rn. 1.

- ^ Rogers Brubaker: Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany , Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts) 1992.

- ↑ Dieter Gosewinkel: Naturalization and Exclusion. The nationalization of citizenship from the German Confederation to the Federal Republic of Germany (= Critical Studies in History , Vol. 150), 2nd edition, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 3-525-35165-8 , p. 424 .

- ^ Hajo van Lengen: Settlement area of the Frisians in northwestern Lower Saxony with today's administrative boundaries. Definition of the settlement area of the Frisians in north-western Lower Saxony (with the exception of the Sater Frisians), which enables the Federal Government to describe and map this settlement area for the purpose of applying the Framework Convention of the Council of Europe for the Protection of National Minorities with the help of administrative boundaries ( PDF ), Report by the “Feriening Frysk Underwiis” for the Federal Ministry of the Interior , 2011, p. 7.

- ↑ Hans Kohn (1951): The Eve of German Nationalism (1789-1812). In: Journal of the History of Ideas. Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 256-284, here p. 257 ( JSTOR 2707517 ).

- ↑ When are immigrants Germans? According to the survey, language should decide - survey on immigration: German is whoever speaks German. In: Spiegel Online . November 30, 2014, accessed July 23, 2016 .

- ^ Hans Kohn: Romanticism and the Rise of German Nationalism. In: The Review of Politics , Vol. 12, No. 4, 1950, pp. 443-472, 459 f. ( JSTOR 1404884 ).

- ^ Hans Kohn: Romanticism and the Rise of German Nationalism. In: The Review of Politics , Vol. 12, No. 4, 1950, pp. 443-472, 460.

- ↑ Stefan Senders (1996): “Laws of Belonging: Legal Dimensions of National Inclusion in Germany.” New German Critique , pp. 147–176, esp. P. 175.

- ↑ Karl Haenchen: Kaiser Wilhelm I. Report on the Berlin March Revolution in 1848. In: White sheets . Monthly for history, tradition and state , ed. by Karl Ludwig Frhr. von und zu Guttenberg, Bad Neustadt / Saale 1934–1943, March 1938, p. 69 (PDF) ( Memento from January 19, 2012 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Michael Mäs / Kurt Mühler / Karl-Dieter Opp: When are you German? Empirical results of a factorial survey. Cologne Journal for Sociology and Social Psychology 57, 2005, pp. 112-134.

- ↑ Bassam Tibi: Leitkultur as a consensus of values. Review of a failed German debate , in: From Politics and Contemporary History 1–2 / 2001.

- ↑ Tatjana Radchenko / Débora Maehler: Still a foreigner or already a German? Influential factors on self-assessment and perception of others by migrants. Conclusion of the 47th congress of the German Society for Psychology , September 26-30, 2010 in Bremen; University of Cologne, 2010.

- ^ A b Felix Grigat: Loss and Gain. Results of current studies on immigration ( Memento from January 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), Research & Teaching , April 2015.

- ^ Society of Muslim social and humanities scholars: Islam in Germany. Future opportunities of our political culture. Joint conference of the Institute for Cultural Studies and the Center for Turkish Studies. 28-29 May 1998 .

- ↑ Christian Jakob: Those who stay. Refugees are changing Germany . In: From Politics and Contemporary History 14–15 / 2016, April 4, 2016, p. 14 ( online ).

- ^ New German , hybrid European-Muslim identity models, projects & associations: Heymat, Humboldt University in Berlin

- ↑ Germanophilia. (No longer available online.) Wissen Media Verlag, June 7, 2010, archived from the original on December 1, 2011 ; Retrieved July 15, 2011 .

- ↑ Johannes Aventinus: Chronica of the origin, act and come of the ancient Germans. Nuremberg 1541.

- ↑ Helmut Wurm: The importance of ancient reports about the Germanic peoples for German nationalism and Germanophile anthropology in Germany in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In: Würzburger medical historical reports , Vol. 14, 1996, pp. 369-401, here p. 376.

- ↑ See in particular on “Prejudices on the inter-ethnic level” Susanne Janssen, Vom Zarenreich in den American Westen: Germans in Russia and Russian Germans in the USA (1871–1928) (= studies on the history, politics and society of North America; vol . 3). Lit Verlag, Münster 1997, ISBN 3-8258-3292-9 , p. 243 .

- ↑ Eike Sanders and Rona Torenz: How anti- German are German schools? In: sächsische.de . January 26, 2011, accessed November 4, 2019 .

- ↑ Katja Füchsel and Werner van Bebber: “Civilizational standards no longer apply”. In: Der Tagesspiegel . November 23, 2006, accessed on October 26, 2019 (interview with the judges Kirsten Heisig and Günter Räcke).

- ↑ Silke Mertins: Religious Mobbing: The researcher Susanne Schröter shows the influence of political Islam in Germany and warns against playing it down. Tip from “Books on Sunday”. In: NZZ am Sonntag. August 24, 2019, accessed October 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Andrea Posor, Christian Meyer: German hostility in schools. Education and Science Union , Landesverband Berlin (GEW Berlin), 2009, accessed on October 26, 2019 .

- ^ Marie Christine Bergmann, Dirk Baier, Florian Rehbein and Thomas Mößle: Young people in Lower Saxony. Results of the Lower Saxony Survey 2013 and 2015. In: Research report no. 131. Kriminologisches Forschungsinstitut Niedersachsen eV, 2017, pp. 39–44 , accessed on October 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany Warsaw: Leaflet on determining German citizenship (PDF)

- ^ Ofer Aderet: German citizenship , Haaretz from July 25, 2007; printed at haGalil.com ( online ).

- ↑ Answer of the federal government to the minor question of the MP Ulla Jelpke and the parliamentary group of the PDS - Printed matter 14/4006 - Promotion of German minorities in Eastern Europe since 1991/1992 ( PDF )

- ^ Council of Europe: Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities

- ^ German-Danish agreement of March 29, 1955 . Section II / 1, p. 4 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Answer of the Federal Government to the minor question of the MP Ulla Jelpke and the parliamentary group of the PDS, printed matter 14/4006 - Promotion of German minorities in Eastern Europe since 1991/1992 ( PDF )

- ^ Deutschtümelei according to Mackensen - Large German Dictionary. 1977.

- ^ Günther Drosdowski: Etymology. Dictionary of origin of the German language - The history of German words and foreign words from their origins to the present. Volume 7, 2nd edition, Dudenverlag, Mannheim 1997 (keyword “deutsch”, p. 123; keyword “welsch”, p. 808).

- ^ Tillmann Bendikowski : The day on which Germany came into being. The story of the Varus Battle. C. Bertelsmann, 2008, ISBN 978-3-570-01097-6 (index on "Barbaren" and "Welsch", pp. 7, 23, 48, 51, 53, 56, 68, 97, 109, 122, 133 , 136, 146, 175 f., 201, 217; the book has set itself the task of freeing the assessment of historical events from all "German messiness").

- ↑ On the regulatory concept of the nation state, see Hans F. Zacher , Social inclusion and exclusion in the sign of nationalization and internationalization , in: Hans Günter Hockerts (Ed.): Coordinates of German History in the Epoch of the East-West Conflict , Oldenbourg, Munich 2004 ( Schriften des Historisches Kolleg: Kolloquien ; 55), ISBN 3-486-56768-3 , pp. 103–152, here pp. 105 f., 141 with further evidence: The constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany as a nation state, but “only with acceptance of Contradictions ”, as well as the character of the united Germany as a nation state.

- ↑ Federal Ministry of the Interior: Second report by the Federal Republic of Germany in accordance with Article 25, Paragraph 2 of the Framework Convention of the Council of Europe for the Protection of National Minorities , 2004, p. 19 Rn. 48 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Armin Nassehi: The double visibility of immigrants. A Critique of the Current Immigration Drama . In: Berliner Republik 1/2001.

- ↑ Naika Foroutan, Isabel Schäfer: Hybrid Identities - Muslim Migrants in Germany and Europe . In: From Politics and Contemporary History , issue 5/2009 from January 26, 2009 ( online ).

- ↑ Branko Tošović: Burgenland Croatian , February 23 2016th

- ↑ Minorities in Austria: Ethnic Minorities - The Austrian Ethnic Groups ( Memento from May 7, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), Initiative Minorities

- ↑ 2nd Austrian report in accordance with Article 25, Paragraph 2 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities , Vienna, September 2006 ( Memento of August 21, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF).

- ↑ Quoted from Helmut Berschin , Concept of Germany in Linguistic Change , in: Werner Weidenfeld , Karl-Rudolf Korte (Ed.): Handbook on German Unity, 1949–1989–1999 , Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 1999, ISBN 3 -593-36240-6 , pp. 217-225, here p. 219 .

- ↑ Christa Dürscheid , Martin Businger (Ed.): Swiss Standard German. Contributions to variety linguistics. Gunter Narr Verlag, Tübingen 2006, ISBN 3-8233-6225-9 , p. 7.

- ^ Josef Frommelt: The Liechtenstein national anthem. Origin, introduction, changes. In: Yearbook of the Historical Association for the Principality of Liechtenstein 104 (2005), pp. 39–45.

- ^ A b Society for Threatened Peoples : Endangered Diversity - Small Languages Without a Future. About the situation of the language minorities in the EU. An overview of the GfbV-Südtirol , November 8, 2000 (section “Belgium - a model with white spots”) .

- ↑ Article 3 of the Loi du 24 février 1984 sur le régime des langues , described and explained by Jacques Leclerc , Luxembourg , in: L'aménagement linguistique dans le monde , Québec, CEFAN, Université Laval, December 13, 2015.