Exiles

History refers to the mostly Protestant religious refugees of the 16th – 18th centuries as exiles . Century, who were driven from their homeland because of their religious beliefs.

Origin of the term

The word is derived from the present participle exulans of the verb exulare (originally: exsulare ), which was formed for the noun exsul for exile . This in turn arose from ex for out of ... and solum for soil or land . Exiles are literally those “living outside their country”. Exilant, on the other hand, is a newer word creation derived from exile (from Latin exsilium , also from exul ).

Historical background

Flight and expulsion for religious reasons had occurred again and again in the West since Christianity became the state religion in the Roman Empire in the 4th century . In the high and late Middle Ages in particular , entire population groups such as the Cathars and Waldensians in southern France or the Hussites in Bohemia saw themselves as heretics . Even the crusade was preached against the Cathars , which ended with their almost complete annihilation.

For the first time since late antiquity, the Reformation in the 16th century created a situation in Europe in which large numbers of princes could profess a denomination that deviated from Catholicism . Previously, if there was usually only the choice between adaptation or annihilation for people of different faiths, they could now count on more or less benevolent acceptance into territories whose sovereign shared or tolerated their confession.

In the Augsburg Religious Peace of 1555, the possibility of emigration was even given a legal basis. According to the principle of cuius regio, eius religio , the ius reformandi stipulated that the sovereigns had the right to determine the denomination of their subjects. The princes, however, granted the Catholic and Lutheran subjects who did not want to convert to their denomination the ius emigrandi , the free right of deduction, in return for a withholding tax.

The ius emigrandi was only a weak outlet in the face of the pressure that the ius reformandi could exert on the conscience of the subjects. After all, Catholics and Lutherans at least now had the right to emigrate to countries of their faith. In this case, they no longer had to fear being prosecuted for violating their subject obligations. Reformed and Anabaptists like the Mennonites were initially exempt from this rule. They continued to be persecuted and driven out by both Catholic and Protestant princes of different faiths. The persecution of the Mennonites "with fire and sword" was even expressly prescribed by several Reichstag resolutions. Over time, however, these resolutions were hardly implemented by a growing number of territories.

It was not until the Peace of Westphalia that the Reformed also achieved equality under imperial law with Catholics and Lutherans. In addition to the right to unhindered emigration, the members of the now three officially recognized denominations had the right since 1648 to practice their faith privately on the territory of a sovereign of a different faith. The Anabaptists and Mennonites were still denied this equality.

In Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, only the residents of Poland and Transylvania enjoyed complete religious tolerance . All other monarchies, especially the Catholic countries Spain and France , took rigorous action against people of different faiths. In England, the civil rights of Catholics were restricted, as was the largely more tolerant Netherlands .

The main streams of exiles

All of this has led to a growing flow of exiles across Europe and the Mediterranean region since the beginning of the 16th century. After the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, Spanish Jews sought refuge in various European states and in the Ottoman Empire . After the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, French Huguenots fled to England, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Germany; they are also referred to as refugees (from the French refuge = refuge). Prussia in particular benefited from the edict of Potsdam by Elector Friedrich Wilhelm von Brandenburg , which resulted in a strong wave of French refugees.

In order to avoid depopulation, the Habsburg Monarchy pursued a policy of suppression after the Peasant Wars, which was only relaxed with the Theresian-Josephine reforms . In addition to the peasantry, the miners and trades in particular were Protestant; they provided an economic basis for the monarchy with salt mining in the Salzkammergut and the iron industry near the Erzberg . Forced conversions and crypto-Protestantism were predominant here. Exceptions were made by the policy of suppression in settlements on the military border with the Ottoman Empire ( Croatia , Slavonia , Banat , Transylvania ), where there was largely religious freedom , also out of consideration for the local Orthodox Christians and Muslims loyal to the emperor. The proportion of the Protestant population in these areas was in the low percentage range.

But Protestants also had to flee in large numbers from the countries of the Habsburgs : In Austria under the Enns (Lower Austria) and above the Enns ( Upper Austria ) as well as in Styria , Carinthia and Carniola , from the end of the 16th century to the 1670s Years, in several waves, forced well over 100,000 Protestants to emigrate. After the urban bourgeoisie, the multipliers of the Protestant denomination (pastors, teachers) and the nobility, after the Thirty Years' War it was mainly the rural population who were affected by expulsions. The names and fates of those affected have now been documented in a large number of publications. Mostly on the way via Regensburg , the expellees moved to the war-depopulated parts of Franconia and Swabia , settled here and contributed to the economic and cultural recovery. Numerous family stories can still be traced back to their exuberant origins.

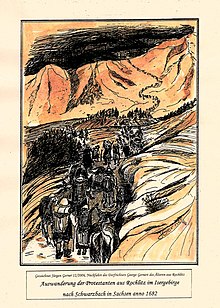

Many Austrian exiles can also be found in Brandenburg and Sweden . The Bohemian Brothers and other German-speaking Protestant Bohemians from the dominions of Friedland, Starkenbach, Harrach, Rochlitz , Hohenelbe, Arnau and Northern Bohemia emigrated to the neighboring Saxony or the Mark Brandenburg . The loss of population due to emigration in Bohemia was 150,000 exiles, which corresponds to 36,000 families. After 1680, Catholic repression led to the nightly exiles of entire Protestant villages. The escape movement created a national disaster. There were repatriation orders from Vienna and Prague and letters of justification from Saxony , which reflected the obscure social conditions. The exiles of the Protestant community of Rochlitz an der Iser on July 15, 1682 in the Bautzen Queiskreis , which the village judge George Gernert led, is a well-documented example.

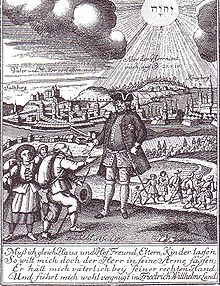

Most of the Salzburg exiles , who were expelled from their homeland in 1731 as a result of the emigration patent granted by Prince Archbishop Leopold Anton von Firmian , found acceptance in West and East Prussia . Another part was under the reign of Charles VI. and Maria Theresa deported to Transylvania (see Landler and Transmigration ). According to the tolerance patent of 1781 it was possible to migrate within the hereditary lands if no tolerance community was approved. How some of the persecuted saw their situation themselves is described in the poem of a Protestant expelled from the Prince Archbishopric of Salzburg :

" I am a poor Exulant ,

so I have to write me.

I am being driven out of the fatherland to

drive God's word.

But I know very well,

Lord Jesus mine,

it was the same for you,

now I am to be your successor,

make it Lord according to your desire! "

While some exiles tried to settle as close as possible to their former homeland , many also emigrated overseas. For example, some Moravian Brethren founded settlements and mission stations between Greenland and South America . Palatine Mennonites and Amish went to Pennsylvania , where their descendants still live today. Mennonites from the Vistula Delta and Pietist groups in turn accepted the invitation of Tsarina Catherine the Great and settled in the areas newly conquered by Russia on the lower Volga .

Emergence of refugee cities and villages

Especially after the devastation of the Thirty Years' War , more and more sovereigns recognized the economic opportunities that resulted from taking in exiles. In the 18th century, King Friedrich II of Prussia laid the foundation for successful internal colonization with edicts and decrees aimed at increasing the population. He called around 60,000 settlers to his country and had around 900 colonist villages built. An expression of this attitude, which is more oriented towards considerations of utility than principle tolerance, is his well-known saying:

"All religions are the same and good, if the people, if they profess, are honest people, and if Turks and pagans came and wanted to poop the country, then we wanted to build them mosques and churches."

As early as the 17th century, some early Enlightenment thinkers had recognized from comparing the Netherlands with Spain that there were connections between religious tolerance and the prosperity of a country on the one hand and between intolerance and economic decline on the other.

There was a simple reason for this: Those who left their homeland for religious reasons had to be able to afford it economically. So mostly those fled who could turn their property into money or who could carry their capital with them in the form of knowledge or manual skills. So it happened that in many cases the exiles soon shaped the economy of their receiving areas and contributed significantly to their prosperity. One example of this is the Musikwinkel in Vogtland , which was settled by Bohemian musical instrument makers.

In Germany in particular, a series of exile cities emerged - mostly on the initiative of the sovereigns - in which refugees of one or more denominations were accepted. A particularly striking example of this is the founding of the city of Neuwied am Rhein , where there was extensive religious freedom for all confessions.

The Neuwied example

The reformed county of Wied was largely impoverished during the Thirty Years' War . Count Friedrich III promised himself from participating in the Rhine trade . zu Wied economic impetus. Therefore, in 1653 he had the new Neuwied residence founded on the narrow Rhine front of his county . In order to attract more residents to the slowly growing and topographically unfavorable settlement, he granted it a town charter privilege in 1662, which guaranteed the residents numerous freedoms - above all the right to extensive religious freedom and civil law equality regardless of their religious affiliation . In the rest of the county, however, only the Reformed Confession was allowed.

This privilege, supported by regular recruitment measures, allowed the population of the young city to grow steadily after 1662. Therefore, the successors of Friedrich III. his policy of religious tolerance in Neuwied. Groups willing to move in received concessions to settle in the context of the Wiedischen Peuplierungspolitik . This meant that they were no longer dependent on the benevolent tolerance of the ruling Princely House, but could instead sue their religious and civil rights in subject trials before the Imperial Court of Justice or the Imperial Court Council . This was an important concession, especially for members of religious communities not recognized under imperial law. Under Friedrich's grandson, Prince Johann Friedrich Alexander zu Wied-Neuwied , members of seven different religious communities lived permanently in Neuwied in the 18th century: Calvinists , who also included the count's house, Lutherans , Catholics , Mennonites , Moravians , inspired people and Jews . At times also had Quakers and French Huguenots settled in the city.

After Neuwied, too, the exiles often brought new branches of industry and skills with them, which brought the town to an economic boom. The furniture from the manufactory of Herrnhuter Abraham and David Roentgen or the artistic clocks from Peter Kinzing were in demand at the royal courts all over Europe .

Since the middle of the 18th century Neuwied has been considered a prime example of a religious sanctuary in the enlightened world . A visitor to the city wrote in a travelogue in 1792: “Anyone who doubts the consequences of the tolerance should come here and be ashamed of their petty beliefs. The confessors of the most diverse religious systems live happily side by side here, and industry and trade flourish under their hands. "

Further examples of refugee settlements

- Bohemian-Rixdorf

- gain

- Estherwalde , Polish Wola Augustowska bei Giebułtów (German Gebhardsdorf )

- Friedrichstadt

- Georgenfeld

- Glückstadt

- Hanau (founded in Hanauer Neustadt in 1597 for religious refugees)

- Herrnhut

- Johanngeorgenstadt

- Karlshafen

- Klingenthal

- Markneukirchen

- Neu-Isenburg

- City of Neusalza

- Nowawes (see also Babelsberg and Potsdam )

- Sprottischwaldau , Polish Szprotawka

- Wain

In some refugee settlements , the exile communities built their own churches, the exile churches ; Sometimes the receiving sovereign or the receiving city had a church for their new citizens built.

literature

- Hans R. Guggisberg (ed.): Religious tolerance. Documents on the history of a claim . Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1984 (modern times under construction. Presentation and documentation, vol. 4)

- Erich Hassinger: Economic motives and arguments for religious tolerance in the 16th and 17th centuries . in: Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte 49 (1958), pp. 226–245

- H. Kamen: Intolerance and Tolerance between Reformation and Enlightenment . Munich 1967

- Helmut Kiesel: Problem and justification of tolerance in the 18th century , in: Festschrift for Ernst Walter Zeeden. Münster 1960 (Reformation history studies and texts; Suppl. Vol. 2), pp. 370–385

- Harm Klueting : Catholic Denominational Migration , in: European History Online , ed. from the Institute for European History (Mainz) , 2012 Accessed on: December 17, 2012.

- Heinrich Lutz (ed.): History of tolerance and religious freedom . Darmstadt 1977 (Paths of Research, Vol. 246)

- Vera von der Osten-Sacken: Forced and self-chosen exile in Lutheranism. Bartholomäus Gernhard's work «De Exiliis» (1575) , in: Henning P. Jürgens, Thomas Weller (Ed.): Religion and mobility, interactions between spatial mobility and religious identity formation in early modern Europe. Colloquium of the Institute for European History from February 12 to 14, 2009, Göttingen 2010, (VIEG supplement 81) pp. 41–58.

- Vera von der Osten-Sacken: Exul Christi: Denominational migration and its theological interpretation in strict Lutheranism between 1548 and 1618 , in: European History Online , ed. from the Institute for European History (Mainz) , 2013, accessed on August 29, 2013.

- Hermann Schempp: Community settlements on a religious and ideological basis . Tubingen 1969.

- Werner Wilhelm Schnabel: Upper Austrian Protestants in Regensburg. Materials on Civil Immigration in the First Third of the 17th Century. In: Communications from the Upper Austrian Provincial Archives. Vol. 16, Linz 1990, pp. 65-133, online (PDF) in the forum OoeGeschichte.at.

- Werner Wilhelm Schnabel: Austrian exiles in Upper German imperial cities. On the migration of ruling classes in the 17th century (= series of publications on Bavarian national history, 101). Munich 1992.

- Werner Wilhelm Schnabel: Austrian religious refugees in Franconia. Integration and assimilation of exiles in the 17th century . In: Hans Hopfinger, Horst Kopp (ed.): Effects of migrations on receiving societies. Lectures of the 13th interdisciplinary colloquium in the central institute . Neustadt / A. 1996 (Writings of the Central Institute for Franconian Regional Studies and General Regional Research at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, 34), pp. 161–173.

- Werner Wilhelm Schnabel: Exulantenlieder. About the constitution and consolidation of self and external images with literary means . In: Mirosława Czarnecka, Thomas Borgstedt, Tomasz Jabłecki (eds.): Early modern stereotypes. On the productivity and restrictiveness of social ideational patterns. 5th Annual Meeting of the International Andreas Gryphius Society Wrocław October 8-11, 2008 . Bern u. a. 2010 (Yearbook for International German Studies, Series A - Congress Reports, 99), pp. 317–353.

- Alexander Schunka: Lutheran Denominational Migration , in: European History Online , ed. from the Institute for European History (Mainz) , 2012, accessed on: June 6, 2012.

- Wilfried Ströhm: The Moravian Brethren in the urban fabric of Neuwied . Boppard 1988

- George Turner: We take home with us, A contribution to the emigration of Salzburg Protestants in 1732, their settlement in East Prussia and their expulsion in 1944/45 . Berlin 2008

- Stefan Volk: Peuplication and religious tolerance. Neuwied from the middle of the 17th to the middle of the 18th century , in: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter 55 (1991), pp. 205–231

- Wulf Wäntig: Borderline experiences. Bohemian exiles in the 17th century . Constance 2007

- Ernst Walter Zeeden: The Age of Faith Struggles . Munich 1983 (Gebhardt Handbook of German History, Vol. 9)

- George Gernert : History of the Rochlitz religious refugees from the Jizera Mountains 1682

See also

- Moravian Brethren

- Mennonite emigration

- Round church "To the Prince of Peace"

- History of violin making in Klingenthal

- Zillertal inclinants

Web links

- Exile Research Society for Family Research in Franconia eV

- Names of exiles in the Weißenburg area Stadtwiki Weißenburg

- Family names of the Salzburg emigrants Salzburg WIKI

-

The story of an exile family from their point of view: 1652 flight and expulsion from Austria.

- Monuments for exiles www.pfaenders.com

- Digitization of the so-called Bergmann's collection of exiles

- Danièle Tosato-Rigo: Protestant religious refugees. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- History of Joseph Schaitberger from the perspective of his descendants in the USA (Engl.)

- North Bohemian exiles from Platten, 1653: http://www.im-vertrauen-bauen.de/fileadmin/portal/www.im-vertrauen-bauen.de/pool/15_Rathe.pdf

Individual evidence

- ^ Werner Wilhelm Schnabel: Austrian exiles in Upper German imperial cities. On the migration of ruling classes in the 17th century . Munich 1992 (series of publications on Bavarian national history, 101).

- ^ Eberhard Krauß: Exiles from the western Waldviertel in Franconia (approx. 1627-1670). A family and church history investigation . Nuremberg 1997 (sources and research on Franconian family history, 5); Friedrich Krauss: Exiles in the Evangelical Lutheran Church. Deanery Feuchtwangen. A family history investigation . Nuremberg 1999 (sources and research on Franconian family history, 6); Konrad Barthel: Exiles and immigrants in the Evangelical Lutheran Deanery Altdorf near Nuremberg from 1626 to 1699 (including the Evangelical parish Fischbach, which belonged to the Dean's office until 1972) . Nuremberg 2000 (sources and research on Franconian family history, 7); Manfred Enzner: Exiles from the southern Waldviertel in Franconia. An investigation into the history of families and manors . Nuremberg 2001 (sources and research on Franconian family history, 8); Gerhard Beck: Austrian exiles in the Evangelical Luth. Deanery areas Oettingen and Heidenheim . Nürnberg 2002 (sources and research on Franconian family history, 10); Eberhard Krauss, Friedrich Krauss: Exiles in Evang.-Luth. Deanery Ansbach. A family history investigation . Nuremberg 2004 (sources and research on Franconian family history, 13); Manfred Enzner, Eberhard Krauss: Exiles from the Lower Austrian Eisenwurzen in Franconia. A family and church history investigation . Nuremberg 2005 (sources and research on Franconian family history, 14); Eberhard Krauss: Exiles in the Evangelical Luth. Deanery Leutershausen. A family history investigation . Nuremberg 2006 (sources and research on Franconian family history, 15); Eberhard Krauss: Exiles in the Evangelical Luth. Deanery District Nuremberg. A family history investigation . Nuremberg 2006 (sources and research on Franconian family history, 16); Eberhard Krauss: Exiles in the Evangelical Luth. Deanery Windsbach in the 17th century. A family history investigation . Nuremberg 2007 (sources and research on Franconian family history, 19); Manfred Enzner, Eberhard Krauss: exiles in the imperial city of Regensburg. A family history investigation . Nuremberg 2008 (sources and research on Franconian family history, 20); Eberhard Krauss: Exiles from the Upper Austrian Mühlviertel in Franconia . Nuremberg 2010 (sources and research on Franconian family history, 23); Eberhard Krauss: Exiles in the Evangelical Luth. Deanery Markt Erlbach . Nuremberg 2011 (sources and research on Franconian family history, 26); Eberhard Krauss: Exiles in the earlier Evangelical Lutheran. Deanery Markt Erlbach in the 17th century . Nuremberg 2011 (sources and research on Franconian family history, 26); Karl Heinz Keller, Werner Wilhelm Schnabel, Wilhelm Veeh (arr.): Carinthian migrants of the 16th and 17th centuries. A personal history index . Nuremberg 2011 (gff digital - series B: personal history databases, 1); Eberhard Krauss: Exiles in the Evangelical Luth. Deanery Neustadt an der Aisch . Nuremberg 2012 (sources and research on Franconian family history, 27); Eberhard Krauss: Exiles in the Evangelical Luth. Deanery Wassertrüdingen. Nuremberg 2014 (sources and research on Franconian family history, 28).

- ^ Herbert Patzelt (contributions from Hans Pichler, Josef Purmann): The old home, Tschermna, The story of a village in the foothills of the Giant Mountains . In: Heimatkreis Hohenelbe / Riesengebirge e. V. (Ed.): Local books . tape 12 . Benedict Press, Münsterschwarzbach Abtei 2008, p. 106 .

- ^ Sources on the history of the Starkenbach rule in the Riesengebirge in the 17th century by Fanz Donth, Hans H.Donth, Munich -Collegium Carolinum, Verlag Robert Lerche on p. 378 ff., 389-403 (Nath.Müller; Gernert) and Bergmann- List in the Dresden State Archives ; as an internet list of the University of Munich

- ↑ Stefan Volk: Peuplication and religious tolerance. Neuwied from the middle of the 17th to the middle of the 18th century , in: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter 55 (1991), pp. 205–231

- ↑ cit. according to Stefan Volk: Peuplication and religious tolerance. Neuwied from the middle of the 17th to the middle of the 18th century , in: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter 55 (1991), p. 205

- ^ History of Gebhardsdorf in the Queiskreis, State Archive Saxony Bautzen, tax recession

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: Business in the early modern period. Munich 1990. pp. 10, 33, 37, 44

- ↑ Documents from the Grünberg City Archives in Poland, Sprottau Stadtgemeinde Sprottischwaldau, http://wiki-de.genealogy.net/Sprottischwaldau