Ludwig III. (Bavaria)

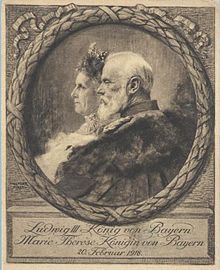

Ludwig III, King of Bavaria (born January 7, 1845 in Munich ; † October 18, 1921 at Nádasdy Castle in Sárvár , Hungary ), was Prince Regent from 1912 and the last King of Bavaria from 1913 to 1918 . With its over the November Revolution just before the end of the First World War took place deposition 738-year-long reign ended on November 7, 1918 Wittelsbach - Dynasty over Bavaria.

Early years

Ludwig was born in Munich in the electoral rooms of the Munich residence as the eldest son of the future Prince Regent Luitpold and Princess Auguste Ferdinande of Habsburg-Tuscany . On the day of his birth he was baptized in the throne room of the Munich Residenz in the name of his grandfather, King Ludwig I , who took over the sponsorship. His siblings were Leopold (1846–1930), Therese (1850–1925) and Arnulf (1852–1907). Through his grandmother Maria Anna , Ludwig, whose family of the Pfalz-Birkenfeld sideline belonged to the Wittelsbach family, also descended from the Bavarian prince-elector line of the Wittelsbach family.

From 1852 to 1863 the artillery officer Ferdinand Ritter von Malaisé acted as his tutor and tutor, supported from 1855 by Heinrich von Vallade . A visit to Greece with his brother Leopold was canceled in early 1862 after the first riots had broken out. A few years later, Ludwig renounced his claims to the Greek throne in favor of his brother, after his uncle Otto of Greece had abdicated anyway.

Ludwig studied philosophy, law, history and economics at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich in 1864/65 . For his studies, he attended public courses at Munich University and did not, as usual, have professors come to his home for private lessons.

In 1866 he took part in the war against Prussia . In the Main Campaign he was wounded as his father's orderly officer on July 25, 1866 near Helmstadt , which contributed to the fact that he was rather averse to the military.

Ludwig married Marie Therese , Archduchess of Austria-Este and Princess of Modena, in Vienna on February 20, 1868 . In the same year he took over the honorary presidency in the central committee of the agricultural association.

Since June 23, 1863, Ludwig was a member of the Chamber of Imperial Councils . In 1870 he voted as a member of the Reichsrat to accept the November Treaties . In 1871 he ran unsuccessfully for the Bavarian Patriot Party in the first Reichstag elections .

In 1875 Ludwig bought Leutstetten Castle and turned it into an agricultural model estate. Otherwise Ludwig was very economical and a rather hesitant person who thought about all his actions and did not come to decisions easily. Unlike his father and grandfather, Ludwig was not very interested in art.

Heir to the throne

Due to the childlessness of the sons of his uncle Maximilians II and the beginning of his father's reign in 1886 it was clear early on that Ludwig, or his descendants, would inherit the crown of Bavaria. In 1887 Ludwig moved into the Wittelsbacher Palais . He continued to devote himself to the study of agriculture, promoting the canal system, and participating in a variety of public affairs, excelling as a speaker. Martha Schad , however, quotes a letter in her book Bayerns Königinnen in which Ludwig confesses to his future wife that he is not a great speaker and that he hates public lectures.

In 1896 he was made an honorary member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences . In the same year there was an uproar in Moscow when Ludwig refused to be welcomed merely as a member of the "retinue" of Prince Heinrich of Prussia and the "accompanying German princes" at the tsar's coronation celebrations . In 1901 he was promoted to Dr. ing. from the Technical University and Dr. oecon. of the University of Munich. In 1906 he campaigned for the Bavarian electoral law reform, which SPD founder August Bebel praised: "If the German people were allowed to choose the Kaiser from one of the German princes, they would probably have chosen the Wittelsbacher Ludwig and not the Prussian Wilhelm I. "

Prince Regent of Bavaria

After the death of his father Luitpold, Ludwig succeeded him on December 12, 1912 as Prince Regent of Bavaria. At that time, the nominal king was his cousin Otto I , who had been insane since his youth and was incapable of governing when he ascended the throne in 1886 .

As early as autumn 1912, the Council of Ministers was discussing a proclamation of the king for Ludwig, but exploratory talks revealed that the majority of the center faction would not support the necessary constitutional amendment.

In October 1913, the topic came back on the agenda after extracts of a legal opinion written by Karl von Unzner became known, which declared the current reign to be unconstitutional by a proclamation. A change in the Bavarian constitution , which the center was now ready to adopt, finally created the fundamental possibility of ending the reign in the event of a long-term illness of the king and allowing the next Wittelsbacher to ascend to the Bavarian throne. Contrary to what is often claimed, the initiative for this constitutional amendment did not come from Prince Regent Ludwig, but from his ministers, particularly Finance Minister Georg Ritter von Breunig . After the Council of State and the two chambers of parliament had given their approval, the law to end the reign came into force on November 4, 1913. On November 5, 1913, Prince Regent Ludwig declared in a declaration signed by the Bavarian ministers that his reign was over and the throne was "finished", with which Otto lost his royal rights. On the same day he was named Ludwig III. proclaimed King of Bavaria. Since the title and dignity of King Otto were not affected, there were two kings in Bavaria until Otto's death.

Even the “Prince Regent's Time”, as the reign of his father Prince Luitpolds is often referred to, is considered to be an era of gradual subordination of Bavarian interests to those of the Reich due to Luitpold's political passivity. In connection with the unfortunate end of the previous rule of King Ludwig II, this break in the Bavarian monarchy had an even stronger effect. The constitutional amendment of 1913 finally brought in the opinion of historians the decisive break in the continuity of the kingdom, especially since this change from the parliament had been granted as a representation of the people and thus indirectly already a step away from the constitutional towards parliamentary monarchy meant. Ludwig III. however, he tried to reassert Bavarian interests as king.

King of Bavaria

Start of government and political priorities

On November 8, 1913, the new king took the oath. On November 12th, he drove from the residence to the service in the Frauenkirche in an eight-horse gilded coronation carriage. For January 1914, Ludwig then scheduled an audience and a dinner for the diplomatic corps from Munich and Berlin. This led to resentment with Kaiser Wilhelm II in Berlin, although Bavaria still had foreign policy competences .

As a king, he went for a walk in Munich without hesitation and met his middle-class friends in a bar on Türkenstrasse . Even after his accession to the throne, Ludwig's passion remained with agriculture, so that people spoke of the “Millibauer” (high German: dairy farmer) on the throne (albeit with respectful affection). The affable and unpretentious manner had quickly made Ludwig the most popular Wittelsbach prince. However, this changed after his accession to the throne, because in the eyes of many contemporaries he now lacked the charisma as a wise monarch and father figure. However, he took the numerous caricatures in this context with humor.

Ludwig's short term in office was strongly influenced by Catholicism . He was close to the center . Its social policy was based strongly on the encyclical Rerum Novarum , which was published in 1891 by Pope Leo XIII. had been announced. With the approval of the Holy See , he founded the festival of the " Patrona Bavariae " in Munich on May 14, 1916, which was celebrated in all Bavarian dioceses in the following years . The Freising Bishops' Conference then decided in 1970 to set the festival date as the beginning of the month of Mary on May 1st. In addition, Ludwig actively campaigned for the expansion of the Ludwig-Donau-Main Canal . On April 14, 1914, Ludwig received the Austro-Hungarian heir to the throne, Franz Ferdinand, as a state guest in Munich, shortly before his assassination led to disaster. While Lower Franconia celebrated its 100th anniversary in Bavaria on June 28, 1914, King Ludwig received a telegram there in Würzburg : The Austrian heir to the throne, Franz Ferdinand, had been assassinated in Sarajevo .

First world war and war aims

When the First World War broke out in late July 1914, Ludwig sent a declaration of solidarity to Kaiser Wilhelm II. With the declaration of a state of war, the framework conditions for Bavaria's military independence changed fundamentally. The army previously sworn in on the Bavarian king was now subordinate to the German Kaiser. However, an official determination of the state of war by the Bavarian king was necessary and since this official Bavarian announcement for the declaration of the state of war by the emperor on July 31 was still missing, the corresponding extra sheets of the Munich newspapers had to be removed from the notice boards. On August 1, 1914, Ludwig III. at the side of his wife from the balcony of the Wittelsbacher Palais from the mobilization known.

A few days later, he expressed that he expected the territorial expansion of Bavaria as the result of a victorious war. Shortly after the outbreak of war, Bavaria in particular stood out among the German federal states in requests for compensation in the event of possible acquisitions by the German Empire. First of all, Ludwig III. the realm of Alsace bordering on the Bavarian Palatinate , later he even cherished great Bavarian dreams of the Rhineland and Belgium and even the Dutch mouth of the Rhine. This happened even though the Belgian queen was a Wittelsbacher at the time. During the World War Ludwig continued to make a name for himself through annexionist demands, which again aimed primarily at Alsace and even parts of Belgium with Antwerp , in order to connect southern Germany to world trade by owning the port city. On June 6, 1915, on the so-called Canal Day, the annual meeting of the Bavarian Canal Association founded in 1891, he demanded direct access from the Rhine to the sea. At the request of the Reich government, the speech on June 8th was only published in the Bayerische Staatszeitung in a weakened form so as not to upset the neutral Netherlands. Ludwig justified this claim with the aim to compensate for Prussian acquisitions and with historical rights of the Wittelsbachers in these areas. This " New Burgundy ", which had already been a political game of thought under the Bavarian Electors Max Emanuel and Karl Theodor in the 18th century, failed because of the rejection of the Chancellor and Prussia, but also because of the other federal states. Bavaria could not even finally secure the acquisition, even of parts, of Alsace in various division projects. Ludwig dropped the demand for the annexation of parts of Belgium in 1916, but still demanded the annexation of Alsace to Bavaria. However, these demands are not only attributable to Ludwig, since z. B. Large parts of the Center Party harbored similar plans. The reason for this lies not least in the fact that in the wake of a German victory a further expansion of Prussian dominance in the empire was feared. The attempt was made to counteract this through independent Bavarian territorial claims. In addition, Bavaria was involved in the war at the highest level and with all its resources. Ludwig's son, the Bavarian Crown Prince Rupprecht , was one of the commanders on the Western Front, while Ludwig's brother Leopold of Bavaria acted as Commander-in-Chief in the East . The replacement of Erich von Falkenhayn by Erich Ludendorff and Paul von Hindenburg on August 29, 1916 (3rd OHL ) brought about a change in the OHL's policy towards the Bavarian War Ministry and Bavarian economy: the Hindenburg program was announced on August 31, 1916 which required drastic measures to increase economic strength. This program set up by Hindenburg and Ludendorff now corresponded to a military dictatorship.

After the Bavarian State Minister for Foreign Affairs and Chairman of the Council of Ministers Georg von Hertling succeeded Reich Chancellor Georg Michaelis in November 1917 , the king did not appoint another central politician, but rather Otto von Dandl , who was independent from the party, as Bavaria's new head of government. Meanwhile, in Munich in June 1916, as a result of the scarce food rationing, the first of a series of hunger demonstrations that never ended until 1918 took place. Negative reports from vacationers at the front worsened the mood. On January 28, 1918, the first strike against the war took place in Bavaria , which was followed by others.

Ludwig III, King of Bavaria (portrait by Walther Firle , oil on cardboard, 1914)

The postage stamp with a stamp of the People's State of Bavaria - after Ludwig's deposition

Attempts at reform and overthrow

During the war, the king became increasingly unpopular. His attitude was perceived as too “ friendly to the Prussians ”. In the course of the worsening food shortage Ludwig was even rumored to be wrongly accused of selling the goods produced on his estate at overpriced prices and only wanting to increase his profit. In February 1918, on the occasion of their golden wedding anniversary, the royal couple donated 10 million marks for charitable purposes. On August 15, 1918, after the German offensive in the West had finally failed, the Bavarian Council of Ministers under Dandl asked the Reich leadership to seek a mutual agreement. The Bavarian Crown Prince also pushed for peace. Now King Ludwig III was also. for the first time for peace negotiations. The more the situation of the population had deteriorated, the more blame was sought "above", whereby this "above" was personalized on the one hand and meant king and queen ("Millibauer", "Topfenresel"), and on the other hand focused on Prussia. Ludwig III. was already seen as an obstacle to a peace process, after all, even during the First World War, he had pursued interest politics in his own favor. In October 1918 Munich became increasingly turbulent and political events both in beer cellars and in the open air were very popular.

Discussed since September 1917, an extensive constitutional reform was concluded on November 2, 1918 through an agreement between the royal state government and all parliamentary groups, which included the introduction of proportional representation . King Ludwig III. agreed on the same day to convert the constitutional into a parliamentary monarchy . The proclamation of the republic only five days later, however, came first.

For the first time on November 3, 1918, on the initiative of the USPD, a good thousand people came together on Theresienwiese to demonstrate for peace and to demand the release of imprisoned strike leaders. In order not to endanger the transition to the parliamentary monarchy in Bavaria, King Ludwig III. the police to restrain, although there were indications of an attempted coup by the USPD.

In the course of the November Revolution , Kurt Eisner proclaimed the Free State of Bavaria on November 8, 1918 and declared Ludwig deposed as king. This made the Bavarian monarch the first German federal prince whom the revolution had driven from his throne. The support of the monarchy had dwindled to such an extent that all Munich barracks, police stations and newspapers were taken by the rebels without resistance.

Despite the long fermenting dissatisfaction among the largely needy population, the rebellion caught the king completely unprepared. He is said to have found out about the outbreak of the revolution from a passerby on November 7th during his daily afternoon stroll in the English Garden . On his return to the residence, he found it largely abandoned by the staff and guards. At around 7 p.m., the first demonstrators appeared in front of the royal residence. Philipp von Hellingrath , the Bavarian Minister of War , had to admit that there were no more troops available in Munich to defend the monarchy. External help could not be expected, as reports of unrest were also available elsewhere. In view of the precarious situation for the king, Ludwig III. by Otto von Dandl and Interior Minister Friedrich von Brettreich temporary escape recommended. Since the king's safety could no longer be guaranteed, his ministers made him leave with the rest of the court in automobiles to Wildenwart Castle in Chiemgau . Together with his seriously ill wife, three daughters, the Hereditary Prince Albrecht and a small court , the king left Munich around 11 p.m. in civilian clothes. The destination of the three rental cars with the refugees was Wildenwart Castle on Chiemsee , but later the entourage had to flee further to the Hintersee in Ramsau near Berchtesgaden . When the king's security seemed threatened here too, it was finally decided to leave Bavaria and seek refuge in Anif Castle near Salzburg in Austria . The Anifer Castle was owned by the Bavarian Imperial Councilor Ernst Graf von Moy, who was absent at the time . In diary entries the daughters of the king, especially Princess Wiltrud, describe the escape of the royal family and the months after in many details.

On November 12, 1918, Dandl, who had been deposed by the revolutionary government on November 8, came to Anif accompanied by an officer sent by Eisner. Ludwig then released the Bavarian officials and soldiers from their oath of loyalty with the Anifer Declaration and thus ensured the continuation of the administration, but refused to abdicate.

Last years

However, the revolutionary government interpreted the Anifer declaration published on November 13 as an abdication and allowed the former king to stay in Bavaria. As "support" he received 600,000 marks. The monarchist officials in the judiciary and bureaucracy essentially retained their positions and acted on hold.

The engagement of his daughter Gundelinde to Count Johann Georg von Preysing-Lichtenegg-Moos on November 24, 1918 was a joy after Ludwig renounced the government. Shortly after Ludwig's temporary return to Bavaria, however, his wife Marie Therese died on February 3, 1919 at Wildenwart Castle .

On February 21, 1919, Kurt Eisner was murdered by the aristocrat Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley , so that Ludwig, who subsequently expected an anti-royalist act of revenge, left Bavaria in a hurry to go to Kufstein . Ludwig then lived first in Tyrol and Liechtenstein and then in exile in Zizers in Switzerland .

In April 1920 he returned to Bavaria, where he lived again at Wildenwart Castle and occasionally went on trips to Lenggries and Berchtesgaden . Ludwig is said to have assured visitors at the time that he would be ready at any time if the people called him. Ludwig's name day on August 25, 1921 was celebrated with great interest from the population and regional politicians. Ludwig, who had been suffering from gastric bleeding for a long time, died on October 18, 1921, during a trip to his Nádasdy castle in Hungary.

burial

After Ludwig's death in Hungary on October 18, 1921, his body was transported eleven days later by train. Thousands of people paid homage to the dead king, the coffin was brought to Wildenwart with a four-in-hand horse and accompanied by numerous club delegations. The last Bavarian royal couple was laid out there until they were transferred to Munich on November 4, 1921. Then was transferred to the two coffins in the Ludwig church in Munich.

As a state funeral did not seem feasible out of consideration for the Reich government , the Bavarian state government entrusted the organization of the funeral to Gustav Ritter von Kahr, the regional president of Upper Bavaria, as a private person. The state government had Kahr assured it that the proclamation of the monarchy was not planned. She acted with the consent of Crown Prince Rupprecht , who only wanted to assert his rights in a legal way.

On November 5, 1921, the funeral procession moved in the traditional ceremonial of the monarchy with the coffins of the royal couple on the six-horse court mourning wagon from the Ludwigskirche to the Frauenkirche . Archbishop Michael von Faulhaber celebrated the funeral service , the funeral speech contained a commitment to the monarchy and divine right. Ludwig was buried with his wife in the Wittelsbach family crypt in the Frauenkirche. After the Second World War, the lower church of the Munich women's cathedral was redesigned by Cardinal Faulhaber. The coffins of the Wittelsbachers buried there were transferred to new wall niches and walled behind grave slabs.

His heart was buried separately and is located in the Chapel of Grace in Altötting .

Awards (selection)

- Order of Hubert (Grand Master)

- House Knight Order of St. George (Grand Master)

- Austrian Military Merit Cross 1st Class on June 13, 1915

Honors

- Dr. rer. pole. hc ( Munich 1872)

- Dr. rer. techn. eh ( TH Munich 1901)

- Honorary member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences (1896)

- Colonel of the Imperial and Royal Infantry Regiment "Rupprecht Crown Prince of Bavaria" No. 43

Numerous regiments, buildings, streets and squares were named after him . In addition, Georg Fürst dedicated the military march "King Ludwig III."

Ancestors and descendants

ancestors

progeny

Ludwig III. married Archduchess Marie Therese of Austria-Este (1849-1919), daughter of Archduke Ferdinand of Austria-Modena and his wife Archduchess Elisabeth Franziska Maria of Austria on February 20, 1868 in Vienna . The marriage had thirteen children:

- Rupprecht (1869–1955), Crown Prince

- ⚭ 1900 Duchess Marie Gabriele in Bavaria (1878–1912)

- ⚭ 1921 Princess Antonia of Luxembourg and Nassau (1899–1954)

- Adelgunde (1870–1958) ⚭ 1915 Prince Wilhelm von Hohenzollern (1864–1927)

- Maria (1872–1954) ⚭ 1897 Ferdinand Duke of Calabria (1869–1960)

- Karl (1874–1927)

- Franz (1875–1957) ⚭ 1912 Princess Isabella von Croy (1890–1982)

- Mathilde (1877–1906) ⚭ 1900 Prince Ludwig Gaston of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1870–1942)

- Wolfgang (1879–1895)

- Hildegard (1881–1948)

- Notburga (* / † 1883)

- Wiltrud Marie Alix (1884–1975) ⚭ 1924 Duke Wilhelm II of Urach (1864–1928)

- Helmtrud (1886–1977)

- Dietlinde (1888-1889)

- Gundelinde (1891–1983) ⚭ 1919 Count Johann Georg von Preysing-Lichtenegg-Moos (1887–1924)

literature

- Alfons Beckenbauer: Ludwig III. of Bavaria 1845–1921. A king in search of his people. Pustet, Regensburg 1987, ISBN 3-7917-1130-X .

- Heinrich Biron: Ludwig III. (= Kingdom of Bavaria series ). TR Verlagsunion, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8058-3769-0 .

- Christiane Böhm (ed.): Just under chandeliers ... The revolution of 1918/1919 from the perspective of the Bavarian royal daughters . Edition Luftschiffer, Munich 2018. ISBN 978-3-944936-52-9 .

- Herbert Eulenberg : The last Wittelsbacher. Phaidon Verlag, Vienna 1929, pp. 264-304.

- Hubert Glaser : Ludwig II. And Ludwig III. - contrasts and continuities . In: Journal for Bavarian State History . tape 59 , 1996, pp. 1-14 . ( Digitized version [accessed on October 23, 2013]).

- Ulrike Leutheusser, Hermann Rumschöttel (ed.): King Ludwig III. and the end of the monarchy in Bavaria. Allitera, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-86906-619-6 .

- Stefan März : The Wittelsbach House in the First World War: Chance and collapse of monarchical rule . Pustet, Regensburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-7917-2497-3 .

- Stefan March: Ludwig III .: Bavaria's last king . Pustet, Regensburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-2603-8 .

- Hans Reidelbach : Character traits and anecdotes from the life of the Bavarian kings Max Josef I., Ludwig I. and Max II. Munich 1895.

- Eberhard Straub : The Wittelsbacher . Siedler, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-88680-467-4 .

- Wolfgang Zorn: Ludwig III .. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 15, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-428-00196-6 , pp. 379-381 ( digitized version ).

Web links

- Literature by and about Ludwig III. in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Ludwig III. in the press kit 20th Century of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Local news. Hof-Nachrichten .. In: Badener Bezirks-Blatt , September 23, 1882, p. 5 (online at ANNO ).

- Locales. In the Weilburg…. In: Badener Bezirks-Blatt , October 14, 1882, p. 2 (online at ANNO ).

- Locales. Hofnachricht .. In: Badener Bezirks-Blatt , October 31, 1882, p. 2 (online at ANNO ).

- tz.de : King Ludwig III .: That was Bavaria's last Kini. Interview with historian Stefan März.

- Armin Greune: Ludwig III., The last Bavarian king . Süddeutsche Zeitung , online version from May 19, 2018, accessed on May 21, 2018.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Traunsteiner Tagblatt, YEAR 2012 NUMBER 46, Bavaria's last king was on the throne for only six years

- ↑ - German protected areas Ludwig III.

- ↑ Schmid, Alois, Weigand, Katharina (ed.): The rulers of Bavaria . CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 978-3-406-54468-2 , p. 384 .

- ↑ Norbert Lewandowski, Gregor M. Schmid: The Wittelsbach House - the family that invented Bavaria: stories, traditions, fates, scandals . Stiebner, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-8307-1060-8 , pp. 211 .

- ↑ Dieter Albrecht : The time of the Prince Regent 1886–1912 / 13. In: Alois Schmid (Ed.): Handbook of Bavarian History . founded by Max Spindler. 2nd completely revised edition. tape 4 . The new Bavaria. From 1800 to the present. First part of the volume. State and politics. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-50451-5 , p. 411 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b Albrecht: Prince Regent Time . Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-50451-5 , p. 412 (1047 p., Limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Supreme declaration on the reign of November 5, 1913.

- ^ House of Bavarian History (HdbG - The Popularity of King Ludwig III.)

- ↑ historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de (Foreign legations in Munich)

- ^ House of Bavarian History (HdbG - The Popularity of King Ludwig III.)

- ↑ Karl-Heinz Janßen : Power and delusion. War target policy of the German federal states 1914/18. Göttingen 1963, p. 26 ff.

- ↑ Everyday Life in World War I - Selected Aspects . City Archives Augsburg; Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ House of Bavarian History (HdbG - The Popularity of King Ludwig III.)

- ^ Stefan March: Ludwig III .: Bavaria's last king. 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-2603-8 .

- ↑ a b E. Ursel: The Bavarian rulers from Ludwig I to Ludwig III. in the judgment of the press after her death . Volumes 10–12 - Volume 11 of contributions to a historical structural analysis of Bavaria in the industrial age. Duncker & Humblot, 1974, ISBN 3-428-03160-1 , p. 168, books.google.de

- ↑ 36th Landtag of the Kingdom of Bavaria (1912–1918)

- ^ House of Bavarian History : Caricature "Majestät, gengs S 'heim, Revolution is!"

- ↑ When the king ripped out. Contemporary history in Martin Irl's archive: Bavaria lost its ruler 90 years ago . In: OberpfalzNetz.de , November 21, 2008

- ↑ Christiane Böhm (ed.): Just under chandeliers ... The revolution of 1918/1919 from the perspective of the Bavarian royal daughters . Munich 2018.

- ↑ Florian Sepp: Anifer declaration, 12./13. November 1918. In: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns . November 12, 2015, accessed December 23, 2015 .

- ↑ The history of the Posthotel Kassl on the hotel's website, see section “King Ludwig III v. Bavaria on his flight to Hungary ”.

- ↑ AZ Press Reader, Ludwig III .: A King reenacted

- ^ Stefan March : The House of Wittelsbach in the First World War: Chance and collapse of monarchical rule . Pustet, Regensburg 2013, p. 525.

- ↑ Dieter J. Weiß : Burial of Ludwig III., Munich, November 5, 1921. In: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns . April 5, 2017, accessed March 10, 2018 .

- ^ In addition, the review by Rainer Blasius : Ludwig der Energiellose. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. November 18, 2014, p. 8.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Luitpold |

Prince Regent of Bavaria December 13, 1912–4. November 1913 |

- |

| Otto I. |

November 5, 1913–8. November 1918 |

(End of the monarchy) |

| Otto I. |

Head of the Wittelsbach House 1913–1921 |

Rupprecht |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ludwig III. |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Ludwig III. from Bavaria |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Bavarian prince, regent and last Bavarian king |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 7, 1845 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Munich |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 18, 1921 |

| Place of death | Nádasdy Castle , Sárvár , Hungary |