Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal

| Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal | |

|---|---|

|

Course of the Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal |

|

| Water code | EN : 2424 |

| location | Germany Bavaria |

| length | 172.4 km |

| Built | 1836 to 1846 (abandoned in 1950) |

| Beginning | Junction from the Danube in Kelheim |

| The End | Confluence with the Regnitz in Bamberg |

| Descent structures | 100 locks from Kelheim to Bamberg |

| Ports | Kelheim, Beilngries, Neumarkt in the Upper Palatinate, Nuremberg, Fürth, Erlangen, Forchheim, Bamberg |

| Historical precursors | Carolina fossa |

| Used river | Altmühl, Regnitz |

| Outstanding structures | Trough bridges Schwarzach-Brückkanal and Gauchsbach-Brückkanal |

| Information center, museum | Canal Museum, Burgthann |

| Kilometrage | from Kelheim km 0 to Bamberg km 172.4 |

| The Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal was the forerunner of the Main-Danube Canal. | |

| Schwarzach-Brück Canal, 2010 | |

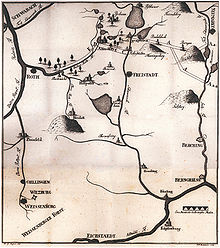

The Ludwig Canal (also Ludwigskanal was called or regional "Old Port") in the 19th and 20th centuries, a 172.4 km long waterway between the Danube at Kelheim and the Main at Bamberg . In a broader sense, the canal, built between 1836 and 1846, was part of a navigable connection between the North Sea near Rotterdam and the Black Sea near Constanța . By crossing the European main watershed , the ambitious construction project took on a special position. 100 locks, some in the Altmühl and Regnitz rivers , managed a total difference in altitude of 264 meters (80 m ascent from the Danube and 184 m descent to the Main). The successor to the canal, which was closed in 1950, is the Main-Danube Canal, which was built between 1960 and 1992 .

Between Beilngries and Nuremberg , the Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal has largely been preserved in its historical scope and with some functions. In 2018 it was named a Historic Landmark of Civil Engineering by the Federal Chamber of Engineers .

course

The Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal, which is no longer navigable except for two sections, officially began at kilometer 0 at the junction from the Danube in Kelheim. In the Lower Bavarian city there is lock 1 in a short connecting canal from the Danube to the Altmühl and at its head the former canal port. For the further course, the bed of the Altmühl was made navigable up to km 32.9 and lock 13 near Dietfurt an der Altmühl . Then the Stillwasserkanal began, which initially ran further west to Beilngries in the Ottmaringer Valley. The canal bed of the Ludwig Canal between Kelheim and Beilngries was largely built over in the 1980s and 1990s by its historical successor, the Main-Danube Canal (MDK).

Before Beilngries, the course of the old canal branches off to the north. The now largely preserved but dry canal bed follows the Main-Danube Canal and the Sulz, which runs a few kilometers to the west . A 65 km long section begins north of Beilngries, where the canal still carries water and most of the structures such as locks and bridges have been preserved. At Mühlhausen (Upper Palatinate) , the new canal leaves the route of its historic predecessor, which continues north to Neumarkt in the Upper Palatinate .

Before Neumarkt in the municipality of Sengenthal , the Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal reaches its apex position after lock 32 and a height difference of 80 meters . At 417 m above sea level NN (water level) this 24 km long part of the canal still crosses the main European watershed. At Berg bei Neumarkt in the Upper Palatinate , this section runs to the west. The following lock 33 is only at km 85.8 near Burgthann in the district of Nürnberger Land .

The Ludwig Canal reaches the city of Nuremberg via Röthenbach near Sankt Wolfgang , Wendelstein and Worzeldorf . After lock 72 (km 108.2), the canal's water disappears in an overflow structure and a pipe that leads to the Main-Danube Canal to the west. Today the canal follows a 1.5 km long avenue in Nuremberg-Gartenstadt. The canal bed was filled with earth, which is now covered by grass. The canal path and locks are still clearly visible here.

This is followed by an approximately 40 km long section, which in the 1960s was almost completely covered by the federal motorway 73 (Frankenschnellweg). Only a few remains such as boundary stones or the canal monument in Erlangen remind of the Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal that once ran here between Nuremberg and Forchheim . From Neuses an der Regnitz , the waterway followed the current course of the Main-Danube Canal. There are still some drained locks and lock keeper's houses between Forchheim and Bamberg . In Bamberg's Bug district, the Ludwig Canal merged into the Regnitz at Schleuse 99 and km 169.3 . The actual still water canal thus reached a length of 136.4 km.

The waterway followed the western arm of the Regnitz, which divides in front of Bamberg city center. After lock 100, which is still in use today, the waterway at the so-called Nonnengraben had finally reached the level of the Regnitz. This enabled the last obstacle, the Bamberg mill district, to be avoided. The difference in altitude covered from the apex to this point was 184 meters. The so-called lock 101 is also mentioned in some sources . A weir and this sluice built from 1858 onwards allowed canal ships to navigate the Regnitz up to the mouth of the Main near Bischberg .

Quick overview by location

History of Kelheim on Alt-Essing , New Essing , castle Randeck , Prunn , Riedenburg , Untereggersberg , Obereggersberg , Deising , Meihern , Muehlbach , Griesstetten , Dietfurt , Töging , Ottmaring , Beilngries , Biberbach , Plankstetten , Berching , Mulhouse , Buchberg , Neumarkt , Holzheim , Berg , Rasch , Schwarzenbach , Burgthann , Pfeifferhütte , Gugelhammer , Röthenbach , Wendelstein , Worzeldorf , Gibitzenhof , Nuremberg , Eberhardshof , Doos , Fürth , Steinach , Herboldshof , Erlangen-Eltersdorf , Bruck , Erlangen , Möhrendorf , Baiersdorf , Kersbach , Forchheim , Neuses , Altendorf , Hirschaid , Strullendorf to Bamberg

Planning and construction

prehistory

In the early days, the southern German landscape was still a wilderness that was difficult to access. For the first settlers, the rivers Altmühl and Regnitz were often the only passages. The idea of building a navigable connection between the rivers Rhine or Main and Danube was first realized during the time of the Franconian Empire . Common theories assume that Charlemagne , then still King of the Franks, had the so-called Fossa Carolina (also known as Karlsgraben) built in 793 . This connection, at that time still with dams and rollers instead of locks, connected the Altmühl with the Swabian Rezat near today's town of Treuchtlingen . However, the project could not prevail and was abandoned shortly after its construction. But there are also other theories that speak of a longer useful life. Similar projects were no longer pursued in sparsely populated Europe in the following centuries.

It was not until the 17th century, after the end of the Thirty Years' War , that ideas about creating such a waterway came back to life. In 1656, Eberhard Wasserberg from Emmerich proposed to Prince-Bishop Marquard II. Schenk von Castell of Eichstätt a "Conjunction of the Rheinstrombs Donaw River and other small waters ...". With a letter of recommendation to the mayor and council of the city of Nuremberg, this prompted them to present his idea there.

The alchemist and economic theorist Johann Joachim Becher described in his book Political Discvrs From the Real Causes of the Decline and Decline of Cities, Countries and Republics , published in 1688, a “short but thorough draft of all utilities, mediated by the union of the Rhine with the Danube Making ships available and uniting the Tauber and Wernitz ... ”.

Various proposals and projects to overcome the watershed were also made in the 18th century. In their dissertatio Historica De Danubii Et Rheni Coniunctione , published in 1720 in Regensburg , Christop Zippel and Georg Zacharias Hans suggested a revival of Charlemagne's idea. One illustration shows, among other things, the representation of a ship lift at the Fossa Carolina after the presentation of the 18th century. In 1729 Johann Georg Eckardt illustrated a similar concept in his contribution Conspectus Fossae Carolinae pro conjunctione Danubii et Rheni .

After the French Revolution and with the start of industrialization in Germany in the 19th century, there were further studies and planning. In 1801, the Nuremberg lawyer Michael Georg Regnet suggested in his work Some Pointers for Promoting the Great Project to unite the Danube with the Rhine, to create a canal in the area of the Ludwig Canal, which was later realized. Even Carl Friedrich von Wiebeking , came in 1806 after a trip to the area of Fossa Carolina to conclude a connection between Altmühl and Roth is the best solution. With the Napoleonic Wars , these and other projects took a back seat.

Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal

In the year of his accession to the throne in 1825, King Ludwig I of Bavaria commissioned the royal building officer Heinrich Freiherr von Pechmann to draw up plans for a new attempt. Von Pechmann completed the planning, in which he decided on the Kelheim-Bamberg route, as early as 1830, and in 1832 it was published.

In 1834 Ludwig I passed the law concerning the construction of a canal to connect the Danube with the Main and in 1835 an association was founded to ensure the financing of the canal project.

On July 1, 1836, the work, which was estimated to take six years, began and by the end of 1839 the earthworks were almost complete, only the larger dams had to be worked on for a long time. According to a newspaper report from the end of 1840, 90 locks had been completed, “the ship's towing paths were chaused along the entire length of the canal, the dams were broken, the banks were covered with fruit trees; all lock and canal keepers' houses were partly near completion ”.

However, from 1839 on, problems arose again and again - minor dam breaks had to be repaired. By the end of 1842, the canal had "advanced so far in most places that it appeared suitable for shipping". Nevertheless, in 1843, Pechmann was the first director of the sewer management to retire. The problems with the construction of the canal, especially the necessary demolition and reconstruction of the Schwarzach-Brück Canal, are cited as reasons for the dismissal along with disagreements with Leo von Klenze , the board member of the Supreme Building Authority. Completion was also delayed by the installation of additional weirs in the Altmühl, which was necessary due to experience after a drought in 1842 to guarantee a minimum water depth.

The king ordered the opening of shipping between Nuremberg and Bamberg for May 1843. This took place on May 6, 1843 by festively decorated ships with full cargo, which set off from Bamberg under the thunder of cannons for Nuremberg. Construction work on the southern section lasted until 1845 due to floods and geological problems.

Initially 3,000 and later 9,000 workers were employed on the project. The capital of the corporation, in which the Kingdom of Bavaria held 25%, was 10 million guilders . To sell the shares, a contract was signed with the Rothschild banking house , which promised a four percent return on the share capital from July 1, 1842 if the channel was not handed over to the public limited company in a fully operational manner by then. Thus, contrary to the planned 8 million guilders, the costs came to 17.5 million guilders.

In August 1845, the canal "in all its facilities and accessories ... was considered complete" and the Kelheim – Nuremberg route was opened. On July 2, 1846, after a total of 10 years of construction, the canal was handed over to the stock corporation and on July 15, 1846, the canal monument donated by King Ludwig I was ceremoniously unveiled on Erlanger Burgberg . The king himself, however, was not present at this ceremony. The monument was designed by Leo von Klenze, the group of figures by Ludwig Michael Schwanthaler .

The canal monument represents the union of the Main and Danube (lat. Moenus et Danubius) through an allegory of the two figures lying on top, who join hands over their sources . The inscription reads:

CONNECTED FOR SHIP TRIP,

A WORK BY CARL THE GREAT ATTEMPTED

BY LUDWIG I KOENIG VON BAYERN

AND COMPLETE

MDCCCXLVI."

Expansion and dimensions

Typical cross-section of the canal

The canal was laid out with a depth of 1.46 meters (plus 15 centimeters due to planned silting) and a width at the water level of 15.76 meters (54 Bavarian feet) and at the bottom of 9.92 meters (34 feet). Von Pechmann also chose the dimensions so that the evasive water offers as little resistance as possible to a ship. This required a ratio of almost 1: 4 between the cross-section of the canal (220 square feet ≈ 18.7 m²) and that of a ship lying in the water (57 square feet ≈ 4.80 m²).

The embankment of the canal, inclined at a good 26 °, was paved down to 4 feet from the water level in order to prevent erosion from the impact of waves. The actual canal bed was not paved or compacted. According to observations and his own experiments, von Pechmann considered it completely sufficient to add clay and street mud to the water of a holding for the first few days. The loose soil, which was even sandy over long distances, sealed off sufficiently until the opening, whereby Pechmann expected a water loss of three times the filling amount per year of shipping through seepage and evaporation.

In the deep cuts near Unterölsbach and Dörlbach, von Pechmann did without embankments and thus saved a total of a good 10 m in width. There the canal was given vertical retaining walls.

After several landslides on the northern embankment of the Dörlbach cut , the dam was extensively secured between 2008 and 2012 and opened again for cyclists and hikers in 2013.

Rule ships on the canal

The canal's standard barges at that time were around 24 meters (80 to 84 feet) long, long-timbered barges should not exceed a length of around 30 meters (100 to 104 feet). The width of the ships was limited to about 4.20 meters (14½ feet) at the surface and about 4.00 meters (14 feet) at the bottom. The maximum draft of about 1.16 meters (4 feet), which now appears small, was relatively large for the conditions at the time, given the 70 centimeters depth of the Main and Danube. The rule ships of the rivers, however, were wider than the Ludwig Canal. In Kelheim and Bamberg, the freight had to be reloaded onto the narrower ships. The barges on the Ludwig Canal could carry up to 120 tons of freight. For comparison: the ships on today's Main-Danube Canal belong to the 1200-ton class.

The towpaths along the canal were each a good 2.30 meters wide, on dams a good 2.90 meters. Along the Stillwasser Canal, there were paths on both banks, but only on one side of the Altmühl and Regnitz rivers, which are regulated by dams. At the crossings of the rivers there were ferry boats to cross over the horses.

The ships were pulled in the slack water canal usually by a horse on the rivers of up to three horses, although people were admitted ( towing ). Often the barges had a tow mast to which about 40 to 80 meters long ropes were attached. Towards the turn of the century, the importance of towpaths diminished as steam engines and propellers became more popular .

Locks

Almost two thirds of the once 100 locks are still preserved today, although some have been filled. The lock chambers were 4.67 meters (16 feet) wide and had outer gates 34.50 meters (155 feet) apart . Most of the locks had a third gate that shortened the chamber to about 28.30 meters (97 feet) and made it possible to save money on shorter ships. This third pair of gates did not exist at the locks on the Altmühl, the locks on the Regnitz near Erlangen and the lock 100 in Bamberg, because there was no need to save water.

The difference in level overcome by the locks was between 2.33 meters and 3.20 meters. Each sluice process meant an expenditure of about 10 to 15 minutes. The locks were founded on wooden piles, the walls consisted of stone from the surrounding area combined with semi-hydraulic lime. The lock gates were made of oak and were replaced by falling walls on the head of a number of preserved structures because they were dilapidated.

The smuggling

During the lock, the water balance was first created by a rack-and-pinion-driven contactor (sliding lock ) in the gate and then the gates were opened or closed with rods without having to work against the water pressure. Originally the gates were extended beyond the hinge by long beams and were thus moved as lever arms. However, the beams were sawed off soon after the opening and replaced by the bar method, although more effort was required. This is just one of several changes that were made again and again both during construction and afterwards and - according to von Pechmann's documentation - were often technically not only unnecessary, but even counterproductive. Pechmann does not name the person responsible for this, but allows it to be heard that these were colleagues sponsored "from above".

A lock filling required up to 510,000 liters of water. Since there were no savings basins , the contents of a lock chamber flowed off towards the valley with each lock. One of the main challenges of the project was therefore to supply the canal with sufficient process water without the use of pumping stations, which was still expensive at the time .

The lock keepers

There were 69 lock and canal keeper's houses along the route, which were built according to a model plan that could be adapted in detail depending on the terrain. According to Pechmann, the model plan for the one-story houses also came from him, but was corrected by the architecture committee (headed by Leo von Klenze) so that they could "look good and pleasant". The associated land was intended for growing vegetables and keeping animals for the lock keepers and overseers who lived there.

The lock keepers and their assistants were responsible for both the operation of the locks (an average of three locks) and the maintenance and care of the canal and its facilities. At the top of the hierarchy were the sewer masters who controlled and monitored everything. They also had to collect the land lease and auction the fruit from the 40,000 canal trees planted along the route.

Lock keepers' houses that have been preserved can be found in Nuremberg-Worzeldorf, Burgthann, Sengenthal, Kelheim, Forchheim ( ⊙ ), Schwarzenbruck and Bamberg , among others .

Other structures

Path and road bridges

There were almost 100 bridges over the Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal along the entire length of the canal, including the lock bridges there were 117 and 127 respectively. Around half were stone arch bridges modeled on the Sorger Bridge , the others - for cost reasons - Flat bridges with brick abutments and wooden decks that were used for smaller roads.

Most of the bridges had towpaths under the arch of the bridge. This had the advantage that the ships' draft horses did not have to be unhitched or re-harnessed. There were also nine stone arched bridges without towpaths underneath, which, to Pechmann's “astonishment and displeasure” , were built after models of the Canal du Rhône au Rhin during his absence . Two of them are still preserved, at Gugelhammer Castle and in the Nuremberg Garden City. The canal narrowed to 5.84 m wide at all bridges.

Bridging channels

Overall, the Ludwig Canal was led ten times on trough bridges , so-called bridge canals (today: canal bridges), over rivers, streets and cuttings. Originally 13 bridging channels were planned, but the three largest were replaced by high earth dams for reasons of cost. Today the two bridging canals, which are not far from each other, are over the Schwarzach (17.50 meters high, 14.60 meters span, 90 meters long) and the Gauchsbach (8.50 meters high, 11.60 meters span, 42.50 meters long) receive. The connecting road from Gösselthal to Oberndorf (Beilngries) ( 49 ° 3 ′ 19.2 ″ N , 11 ° 28 ′ 2.4 ″ E ) is spanned by a trough bridge, the Oberndorfer Aqueduct, but the canal no longer carries any water there.

The Schwarzach-Brück Canal, which carries the canal at km 95.2 between locks 59 and 60 ( 49 ° 21 ′ 19 ″ N , 11 ° 12 ′ 20 ″ E ) with a height of 17.50 meters above the river, is valid as a technical masterpiece of the project. The 90 meter long construction made of sandstone blocks grouted with sandstone powder and lime spans the Schwarzachtal with an arch of 14.60 meters span. Architecturally , von Pechmann and later the royal building officer Leo von Klenze based their plans on Roman aqueducts . However, this bridging canal also caused the biggest setback of the project when it, completed in 1841, had to be almost completely removed in 1844 after a few repair attempts.

The reason for this was the clayey earth and sand used to fill the space between the wing walls on the south side , which was produced when the canal was excavated. It swelled when it first flooded in 1843, causing cracks in the outer walls just hours later and threatening to blow them up completely. Von Pechmann had foreseen a swelling and therefore planned a connection of the walls by means of iron wall hooks for stabilization, but underestimated the forces involved. The northern abutment , founded on rock, had been filled with sand from the right bank and therefore remained undamaged. When rebuilding on the old foundations, the inside of the bridge was then left hollow and the abutments closed with vaults. While that on the north side is a small room with a pointed arch, the hall on the south side is reminiscent of a Gothic cathedral.

Larger trough bridges that no longer exist today were the Doos Brück Canal on the Nuremberg-Fürth city limits over the Pegnitz and the seven-arched Truppach Brück Canal over the Wiesent near Forchheim.

Dams and cuttings

Three dams were built to replace the trough bridges that were initially planned. The other 70 or so dams led the canal over flat terrain or protected it in the area of the Altmühl and the Regnitz from the flood that occurs almost every year. In these cases, roads and bodies of water could cross the canal using inexpensive tunnels, so-called culverts. The highest remaining dams of the canal are

- the Kettenbachdamm (18.5 meters high, 435 meters long) and the Gruberbachdamm with openings for the Kettenbach and Gruberbach near Berg near Neumarkt in the Upper Palatinate (km 76),

- The Schwarzenbachdamm (km 84.2) with a street opening , the Distellochdamm (km 84.8, 20 meters high, 319 meters long) with an opening for the Tiefenbach near Schwarzenbach and the Mühlbachdamm (km 86.7, 16 meters high, 205 meters long) ) at Burgthann.

In order to cross higher landscape sections without locks, so-called cuttings had to be created in some places. Except for the Dörlbach cut, for which a shovel excavator with steam engine drive designed by the Nuremberg machine factory Wilhelm Späth was used, the cuts were dug by hand. The deepest cuts were

- the Unterölsbach cut (23 meters deep, 580 meters long) at km 78.9,

- the Dörlbach cut (14.50 meters deep, 870 meters long) at km 82.1,

- the Buchberger cut at km 64.1.

Treidelsteine

Treidelsteine are historical milestones on the banks of the canal. The stones used to be used as a guide for hauliers and shipmen. The kilometers begin at the beginning of the canal in Kelheim and end in Bamberg. There was a large towstone every ten kilometers and a small towstone every kilometer.

Water balance

The water in the canal came mainly from the Schwarzach / Pilsach discharge at the port of Neumarkt in the Upper Palatinate. Guide ditches also carried water into the canal from the Gauchsbach near Feucht and from the Dillberg . The Pilsach-Leitgraben is the only one from which water is still continuously being discharged today, approx. 250 l per second. The entire apex position is designed almost 60 cm deeper, so that a reservoir of over 200,000 m³ of water was available.

In the still water channel, the water level could be regulated through the locks. In order to be able to let the water run off again in a controlled manner when the inflow is too high, 32 so-called forced reliefs (overflows) were installed. Excess water simply ran off through flat spots in the embankment. In addition, there were a total of 38 so-called bottom drains in order to be able to drain a section for maintenance work. The water could be drained here through openings into a stream or river. One of these bottom outlets is located between the bridge canal over the Schwarzach and the neighboring lock 59 on the south side of the bridge. Via it, water can be drained through a narrow, walled canal into the lower Schwarzach. In the area of Altmühl and Regnitz the water level could be regulated within a certain range by weirs. They were mostly located at the level of a lock and also served to protect the locks from flooding.

There were security gates in longer canal sections as well as before and after dams . In the event of a leak, for example through a breach of a dam, the gates closed automatically by the resulting flow and thus prevented the sewer from leaking. These gates were open during normal operation, but were occasionally closed by opening the downhill sluice. For example, maintenance work could be carried out when the water level was lowered. The plate gates built into the gates were used to refill an emptied canal section and to regulate the flow of water.

business

Ports and Landings

Originally, at the opening, there were 7 harbors and 15 other landing sites, called Lände, for loading and unloading the ships . The latter were, in von Pechmann's words, “formed by building a 58 m long vertical quay wall as a bank instead of the embankment, moving this a little to the rear and thereby widening the canal bed by the same amount.” Many lands were created solely at the instigation of the municipalities or companies located on the canal. Such areas were or are for example in Wendelstein , Pfeifferhütte, Rasch and Berching . No fees were charged for their use, the verbal permission of the lock or canal keeper was sufficient. The goods loaded varied depending on the region, so the Pfeifferhütte site was primarily a transhipment point for grain, while in Worzeldorf and Wendelstein, stones from the nearby quarries (see Wernloch ) and bricks were loaded primarily for transport to Nuremberg. Over time, however, the need for such lands apparently increased; the Guide to the German Waterways of 1893 already contained 37.

Ports were mostly bilateral widening of the attitude on different lengths with vertical quay walls and had storage buildings. The most important place on the canal was Nuremberg, which had the largest port (approx. 50 m × 300 m) on the Ludwig Canal.

The old canal ports of Kelheim, Beilngries, Neumarkt in der Oberpfalz, Pfeifferhütte, Wendelstein, Worzeldorf and Bamberg still exist. Old photos show how little has changed there over the years: the warehouse, lock keeper's house, harbor basin, lock and loading cranes have largely been preserved in their original condition.

Other important ports were in Fürth, Erlangen and Forchheim. For loading and unloading, mainly cranes designed and manufactured by the Späthschen Maschinenfabrik with a lifting capacity of 30 quintals were used. They are still in several places on the canal and are still used by the river management there, especially in the Neumarkt harbor. A harbor master was responsible for each port, and his function could also be assigned to a lock or canal keeper.

However, it was possible - even if it was more difficult on the sloping embankments and without cranes - to tie up at any desired point on the canal and take over or unload cargo without a special landing site. The skipper only needed to notify the Canal Directorate about this in good time, but the permit for berthing outside of the country and harbors was subject to a fee; a so-called embankment fee was charged for this.

economy

At a speed of 3 km / h for a horse-drawn ship, a journey from Kelheim to Bamberg, including 10 to 15 minutes per lock and night's rest, took about six days. It was a good two months by ship from Amsterdam to Vienna .

The operation of the canal should also be worthwhile for the investors. For this reason, fees were charged for the use of the Ludwig Canal and its ports, which were published in fee schedules. Every ship navigating the canal was subject to the canal fees, the port fees were only applicable to those who were in a port. The fee schedules were extensive and detailed. In the first fee schedule of 1843, loaded ships were divided into ten different classes according to the cargo, for which the canal fees per hundredweight and mile of the voyage amounted to 0.1 to 1.3 cruisers . For empty ships, the fees were graduated in six size classes, from 8 to 40 cruisers per mile. The minimum amount to be paid was that of an unloaded ship of the respective class, so it was also to be paid for ships loaded with little and little value. As early as 1846 there was the first reduction in fees with a consolidation to only 5 classes of goods with fees of 0.2 to 0.5 kreuzers per hundredweight, further reductions followed in 1853, 1860 and 1863. As a rough guide: in 1850 a liter of beer cost 5 kreuzers.

Loaded and unloaded ships had to pay the canal fee at the first collection point they touched for the entire stretch of canal that they covered with unchanged cargo. Ships that did not touch a collection point on their voyage paid the canal fees at the collection point closest to the point of departure before their departure.

Port fees were incurred for all ships that were in port for business. As long as a ship was loaded or busy with unloading, loading or reloading, the fees in 1843 were between 4 and 20 cruisers per day, depending on the class of ship, half of which was charged for empty ships. If a ship was only in port for the night or for less than 18 hours, there were no port fees. In addition, so-called crane fees were incurred for loading or unloading goods (staggered according to class of goods), as well as weighing fees (0.2 kreuzers per hundredweight) if the port scales were used. The work involved in loading, unloading and reloading was also calculated according to weight, unless it was done by the ship's personnel. If goods were stored on the port area (outdoors or in a warehouse), this was also charged for each month or part thereof.

In 1852 the total income amounted to 160,671 guilders, whereby the share of shipping fees was 145,849 guilders, port and wintering fees were 1,506 guilders and storage and warehouse fees were 6,583 guilders. On the expenditure side, 94,145 guilders ran up in the same year.

The planned annual transport volume on the canal was 100,000 tons, with the canal year running from March to November, with operations being shut down in winter. In the first full year of operation in 1847, a good 175,000 tonnes were transported, until 1850 the amount rose further to just under 196,000 tonnes, which, however, was already the highest. A low of 1853/54, which could be absorbed by lowering fees, was followed by another ten years of strong transport, but then a downward trend that continued until 1895 set in. With a five-year intermediate high around 1900, the amount rose again from a good 80,000 to 150,000 tons, but then fell to a good 60,000 tons by 1912. In 1925 it was around 22,000 tons and in 1940 around 35,000 tons. The freight transported consisted mainly of wood, stones, coal and agricultural products.

The business results did not run quite parallel. After initial losses, profits could be reported from 1850 to 1863, even if they were relatively small at around 50,000 guilders per year. After that you couldn't get out of the red. By 1912 there was a total loss of 2.9 million guilders. One reason for this was the several times necessary, sometimes considerable, fee reductions in order to remain competitive.

This was due to the increasing use of the railway as well as the railway line Nuremberg – Bamberg of the Ludwig-Süd-Nord-Bahn , which was built almost at the same time and runs parallel to the canal . Another important reason was that no through ship traffic between the Rhine and Danube was possible. The ships on the Rhine and Danube were too wide for the canal and the ships built especially for the canal had too great a draft for the Main and Danube.

As early as the 1890s there were ideas for a new, larger Main-Danube Canal, which Prince Ludwig of Bavaria also advocated in 1891. However, the realization should take until the second half of the 20th century.

The use of towpaths as idyllic hiking and biking trails is a development that began around the turn of the century. The hectic pace of the ever more developing industry and the rapidly growing car traffic passed the old canal almost completely. According to contemporary newspaper articles, the canal was no longer viewed by the population primarily as a traffic route, but as an excursion destination, as a place for swimming and fishing. The economic importance decreased, the recreational value increased.

In books and by contemporary witnesses, the so-called cream steamers are described as legendary, with which day trippers in local traffic were shuttled to coffee and cake in canal bars for a few pfennigs . In the 1930s, however, the National Socialists declared this passenger shipping on the Ludwig Canal an undesirable luxury and discontinued steamboat trips. One of the last uses as a waterway was in 1944, when some speedboats were transferred to the Black Sea.

Decommissioning and current use

During the Second World War there were already initial plans to open the canal and to use the bed between Forchheim and Nuremberg as a route for a Reichsautobahn . The canal and its structures were not spared during the war either - there were a few hits by the Allies and, especially in the Fürth area, bridges were still blown by the Wehrmacht towards the end . The damage caused by the Second World War on the Ludwig Canal was repaired very quickly, although after the end of the war it was not entirely clear how the canal should continue. Transport ships still drove in sections, mainly transporting building materials and rubble.

As early as 1950 the canal was finally abandoned, partially drained and, in particular, between Nuremberg and Bamberg, removed and built over. Since the 1960s, the A73 motorway has run along large parts of the old canal route here. The last major intervention was the construction of the Main-Danube Canal in the Ottmaringer Valley and Altmühltal , which destroyed the canal section including locks 2, 3, 7, 8, 9 and 15 to 21.

In the 1970s, with the entry into force of the Bavarian Monument Protection Act (1973), the sections of the canal were systematically recorded as a route monument and placed under monument protection. Since some sub-areas were still missing from the list of monuments, it was subsequently recorded in the early 1980s.

The owner of the once royal facilities is now the Free State of Bavaria, and they are managed by the regional water management authorities . The tasks of the subordinate river management companies include carrying out the necessary maintenance work on the relatively easy-to-maintain canal. This includes the transitions at the locks, the bridge canals, the renovation of the lock chambers and the replacement of the old trees on the canal. Likewise, the canal bed must be freed from accumulated aquatic plants and mud from time to time. In winter, then as now, the ice on the bridge canals has to be crushed so that the expanding ice layer does not damage the structures.

Until the early 1980s, only the most necessary maintenance work was done, since then the maintenance has become more intensive. In 1986 the Gauchsbach and Schwarzach bridges were renovated and the troughs were sealed with bitumen sheeting. Some locks are still working and have even been made functional again by installing new lock gates. These are currently (mid-2008) locks 100, 68, 58, 33, 32, 30, 26, 25, 24, 12 and 1.

In contrast to earlier times - back then, tar oil was used - no impregnating agents may be used today to protect the wood. The wood therefore ages very quickly and gates must be replaced after a maximum of 20 years. In most of the locks, the gate on the upper head was replaced by a concrete drop wall and removed from the lower head without replacement. The aforementioned security gates are still important today and are therefore regularly renewed.

The remaining sections are interesting for day-trippers and are well integrated into cycle and footpaths. The Schwarzach-Brück Canal is the start and finish point of a six-kilometer circular route laid out as a nature trail by the Nuremberg Water Management Office. The section from Worzeldorf to Neumarkt is part of the Five Rivers Cycle Route .

Most of the sections of the canal, which are still flooded today, have to struggle with sometimes massive weeds due to the shallow water depth, the high nutrient content of the water and the lack of mixing, which have to be removed at regular intervals.

The only ships that still regularly operate on the canal are two towing ships from the Nuremberg and Regensburg water management offices, which offer short trips for tourists in the spring and summer months. The Elfriede runs in a section of the apex position near Schwarzenbach, the Alma-Viktoria in the positions of locks 24 and 25 near Mühlhausen.

The Bavarian Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal Museum has been located in the south wing of Burgthann Castle since 1995 .

There are now serious plans for canal museums in other communities. One of the locations is lock 94 near Eggolsheim in the abandoned northern part .

Art on the canal

In the district of Neumarkt in the Upper Palatinate , the Kunst am Kanal project has existed since 2003 , in which three sculptures (groups) have been designed on the Ludwig Canal . These are a field of stelae between Berg and Neumarkt on the road to Beckenhof and the sky ladder south of the connecting road from the Berger district Unterölsbach to Reichenholz in the municipality of Burgthann . The wooden structure called stacking 3 on the Heinrichsburg Bridge near Berg near Neumarkt in the Upper Palatinate was destroyed on March 1, 2008 by hurricane Emma and rebuilt the following year.

See also

literature

- Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal . In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon . 4th edition. Volume 10, Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1885–1892, p. 980.

- Georg Dehio : Handbook of the German art monuments. Bavaria. Volume 1: Francs . 2nd revised and supplemented edition. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich a. a. 1999, ISBN 3-422-03051-4 , pp. 592f.

- Friedrich Birzer: The Ludwigs-Danube-Main Canal, from a building geological point of view. With 12 figs. In: Geologische Blätter für Nordost-Bayern und adjacent areas 1, 1951, 1, ISSN 0016-7797 , pp. 29–37.

- Friedrich Birzer: The canal construction attempt of Charlemagne . With 2 figs. In: Geologische Blätter für Nordost-Bayern und adjacent areas 8, 1958, 4, ISSN 0016-7797 , pp. 171–178.

- Friedrich Birzer: The dam slides on the Ludwig Canal near Ölsbach . With 5 illustrations in the text. In: Geologische Blätter für Nordost-Bayern und adjacent areas 24, 1974, 4, ISSN 0016-7797 , pp. 285-291.

- Friedrich Birzer: The Schwarzach-Brück Canal . With 6 illustrations in the text. In: Geologische Blätter für Nordost-Bayern und adjacent areas 30, 1980, 3/4, ISSN 0016-7797 , pp. 196-202.

- Bruno von Freyberg: Finds and advances in geological history during the construction of the Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal . With 4 illustrations in the text. In: Geologische Blätter für Nordost-Bayern und adjacent areas 22, 1972, 2/3, ISSN 0016-7797 , pp. 100-125.

- Stefan M. Holzer: The Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal. Federal Chamber of Engineers Berlin 2018. ISBN 978-3-941867-31-4 . Series " Landmarks of Civil Engineering " Volume 22

- W. Kanz, WA Schnitzer: Stalactite formation and water chemistry in the drainage tunnel of the Ludwig Canal near Ölsbach (p. 6634 Altdorf near Nuremberg) . With 3 illustrations and 2 tabs in the text. In: Geologische Blätter für Nordost-Bayern und adjacent areas 28, 1978, 2/3, ISSN 0016-7797 , pp. 136-146.

- Herbert Liedel, Helmut Dollhopf: The old canal then and now. Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal. Stürtz, Würzburg 1981, ISBN 3-8003-0154-7 .

- Herbert Liedel, Helmut Dollhopf: The old canal - the new canal. Loss of landscape in the Altmühltal. Stortz, Würzburg, 2nd edition 1993. ISBN 3-8003-0456-2 .

- Herbert Liedel, Helmut Dollhopf: 150 years old sewer. Tümmels, Nuremberg 1996. ISBN 3-921590-41-8 .

- Martin Eckoldt (Ed.): Rivers and canals, The history of the German waterways. DSV, Hamburg 1998, pages 458-461, ISBN 3-88412-243-6 .

cards

- Bavarian Land Surveying Office: Area map - topographic maps of Bavaria. Altmühltal Nature Park, eastern part - Parsberg, Riedenburg, Mainburg, Regensburg-West, Kelheim. Altmühl-Panoramaweg, Jakobsweg, Juraweg. With hiking trails u. Bike trails. UTM grid f. GPS. The map of the Altmühltal Nature Park. 1: 50,000. ISBN 3-86038-422-8

- Bavarian State Surveying Office: Topographic map 1: 25,000 (TK 25) ( in the order of the route from Kelheim to Bamberg ):

- 7037 Kelheim, 7036 Riedenburg, 7035 Schamhaupten, 6935 Dietfurt ad Altmühl, 6934 Beilngries, 6834 Berching, 6734 Neumarkt idOPf., 6634 Altdorf b. Nuremberg, 6633 Feucht, 6632 Schwabach, 6532 Nuremberg, 6531 Fürth, 6431 Herzogenaurach, 6331 Röttenbach, 6332 Erlangen Nord, 6232 Forchheim, 6132 Buttenheim, 6131 Bamberg Süd, 6031 Bamberg Nord.

Web links

- www.ludwig-donau-main-kanal.de , website of the Neumarkt district and the water management offices

- Hans Grüner's “The Old Canal” - richly illustrated

- Gerhard Wilhelm's channel pages

- Canal pages by André Kraut

- Course of the Ludwig Canal for Google Earth

Individual evidence

- ^ Website of the Federal Chamber of Engineers and Stefan M. Holzer: The Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal. Federal Chamber of Engineers Berlin 2018. ISBN 978-3-941867-31-4 .

- ↑ Complete course of the former canal in OpenStreetMap

- ↑ Ralf Molkenthin: Roads made of water, technical, economic and military aspects of inland navigation in Central Europe in the early and high Middle Ages . LIT Verlag, Münster 2006, ISBN 3-8258-9003-1 , p. 54-81 .

- ^ M. Eckoldt (Ed.), Rivers and Canals, The History of German Waterways, pages 451–457, DSV-Verlag 1998

- ^ Zippel, Christoph; Haas, Georg Z .: Dissertatio Historica De Danubii Et Rheni Coniunctione, A Carolo Magno Tentata. In: Bayerische StaatsBibliothek digital / Munich Digitization Center. Zippel, Christoph; Haas, Georg Z., May 15, 1720, accessed June 30, 2019 (Latin).

- ^ Heinz Zirnbauer: Rhine-Main-Danube. The story of an idea in pictures . GAA-Verlag, Nuremberg 1962.

- ↑ Michael Georg Regnet: Some pointers to the promotion of the big project to unite the Danube with the Rhine. Bauer- und Mannische Buchhandlung, Nuremberg 1801 ( online ).

- ↑ a b c exhibition catalog 1972 (PDF; 123 kB)

- ^ Heinrich Freiherr von Pechmann: The Ludwig Canal - A short description of this Canal’s . Munich 1846 (PDF; 359 kB)

- ↑ a b The Old Canal - Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal. In: nuernberginfos.de. Retrieved November 14, 2018 .

- ^ Friedrich Schultheis: The Ludwig Canal - Its origin and importance as a trade route . Nuremberg 1847, p. 42 (PDF; 706 kB)

- ↑ Annual Report 1851, p. 1 (PDF; 37 kB)

- ↑ www.beilngries.de : Gösselthal - At the entrance to the Sulztal, bordering the Rhine-Main-Danube Canal, is the idyllic hamlet of Gösselthal.

- ↑ Bottom indulgences

- ^ Canal fees from 1843

- ↑ a b Annual Report 1851 (PDF; 37 kB)

- ↑ a b Memorandum on the Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal . Munich 1914, p. 18 ff. ( Memento of February 7, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 229 kB)

- ↑ Herding Ludwig Canal press report from January 17, 2015