Temporary employment

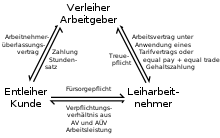

Temporary employment (short: ANÜ ; also: temporary work ) occurs when employees (temporary workers) are made available by an employer (lender) to a third party (hirer) for a fee for a limited period of time. The lender assumes the rights and obligations of the employer.

Further synonyms are temporary work , employee leasing , personnel leasing and temporary work .

Legal basis

The legal basis for the activities of the lender is in Germany the Employment Act (AÜG) in Austria , the Personnel Leasing Act (AÜG). These laws serve to implement the European Directive 2008/104 / EC Temporary Agency Work. Art. 19ff apply in Switzerland. AVG (Employment Agency Act).

history

The origin of the temporary employment lies in the USA . The lawyers Elmer L. Winter and Aaron Scheinfeld needed a secretary to prepare a legal document . When looking for a competent employee, it became clear to them that the new typist could only get a contract for a short time. From this and from the fact that no one from another company was available to them at short notice, they developed an idea: the principle of temporary employment. As early as 1948 they founded the company Manpower Inc. in Milwaukee . This concept experienced a rapid upswing in the USA. The expansion continued in Europe . 1956 opened offices in Paris and London .

General

Temporary workers

The temporary worker is in an employment relationship with the lender. This compared with the applicable employment contracts , collective agreements and statutory employment rights. The temporary employment relationship is subject to the same protection against dismissal as any other employment relationship. His performance does not provide the temporary worker with the lender, but the borrower. The right to issue instructions is transferred to the borrower, who bears joint responsibility for occupational safety . Only the lender may punish behavior in breach of instructions and obligations.

Lender

The contract between the temporary worker and the lender is an employment contract with all rights and obligations. The difference is that the employer is entitled to leave the employee to a third party ( Section 613 sentence 2 BGB ). The contractual relationship between the lender and the borrower is regulated by an employee leasing contract (AÜV). The lender (as a rule) does not guarantee the quality of the work done and no liability for any loss of work. The liability of the lender towards the borrower is limited from the point of view of a fault in selection to the fact that the temporary worker corresponds to the requested qualification. The lender remains jointly responsible for compliance with the accident prevention regulations and other regulations on occupational safety, even in the event of any other regulation in the internal relationship with the borrower. In the case of commercial leasing, an hourly rate is usually agreed between the lender and the hirer for the working time to be performed, which is not identical to the employee's wages. In engineering jobs, three times the gross wage of the temporary worker is common. Young engineers generate a turnover of € 10,000 / month for the rental company.

In his article "Hartz and more - To reduce unemployment through temporary work", Wolfgang Ochel explained in 2003 how rental companies calculate the hourly rate for temporary workers in Germany:

| Hourly rate calculation | to hum |

|---|---|

| + Rental fee |

€ 14.00

|

| - Gross hourly wage of the temporary worker (formerly wage group 1) |

€ 6.50

|

| - Social security share of the lender |

€ 1.34

|

| - Other imputed costs (vacation, illness, etc. of the employee) |

€ 1.63

|

| - Other internal costs (personnel costs for "internal" employees, office, etc.) |

€ 3.69

|

| = Income of the lender (before taxes) |

€ 0.84

|

This calculation scheme of the IFO Institute from 2003 shows that the calculation factor on the gross hourly wage of the lender is around 2.0. If you multiply the gross hourly wage by this calculation factor, you get the rental fee for the rental company. The yield decreases for the lender when work protective clothing is required (eg. B. safety shoes , Blaumann , goggles , etc.) or if the rental term of the temporary employee is not 100% (eg., By order-free periods etc.). On the other hand, it increases the longer the working time in the same position, because the greatest costs arise in recruiting and placement.

The figures from this calculation example are now outdated (see section on remuneration ), so that one can effectively assume a surcharge of around 170–190% for the calculation rates (as of 2014).

Borrower

The hirer uses the labor of the temporary worker without resulting in any claims under labor law, as there are no direct contractual ties to the temporary worker. If the contract on the leasing of workers between the lender and the borrower is ineffective, this leads to the fact that an employment relationship between the temporary worker and the borrower comes about through legal fiction ( § 10 AÜG). In the context of "subsidiary liability" the borrower is liable according to § 28e Abs. 2 SGB IV and § 150 Abs. 3 SGB VII for the social security contributions not paid by the lender despite a reminder to the social insurance carriers ( health insurances , professional associations ) and according to § 42d Abs. 6 EStG for unpaid income tax .

The hirer employs temporary workers in order to meet its labor needs during peaks in demand or long-term absence due to illness. This gives him the opportunity to have a smaller permanent workforce and thus reduce his entrepreneurial risk in the event of a bad order situation. In Germany, a hirer benefits indirectly when the collective agreements for temporary work - as in most cases - provide for lower wages than the collective agreements that apply to the hirer's industry. The applicability of such collective agreements was limited in time with the new version of § 8 AÜG that came into effect on April 1, 2017 .

Temporary employment in Germany

Development of the framework

The term temporary work comes from the beginnings of the industry in Germany. In October 1960, Günter Bindan founded the first German temporary employment agency under his name in Bremen . When the AÜG was introduced in 1972, the maximum leasing period for temporary workers was limited to three months. In 1982 temporary work in the construction industry was essentially banned, in 1985 the maximum duration of employment was extended to six months and subsequently gradually to 24 months.

On January 1, 2003, the then Federal Minister for Economics and Labor in the Schröder government , Wolfgang Clement , repealed several legal framework conditions for temporary work from the Temporary Employment Act (AÜG) without replacement in the course of Agenda 2010 for the purpose of “ making the labor market more flexible ” . A new principle of equal treatment was introduced to compensate for the abolition of the restriction on the maximum lease period, the ban on fixed-term contracts, the ban on reinstatement and the ban on synchronization. With this, temporary workers should be formally equated with permanent employees with regard to wages, vacation and working hours (so-called equal pay and equal treatment). However, the Minister Wolfgang Clement waived a legally immovable stipulation and added the restrictive wording "A collective agreement can permit deviating regulations" to the legal text.

On February 24, 2003, the collective bargaining association CGZP concluded the first deviating nationwide collective bargaining agreement for temporary employment agencies with the Northern Bavarian Temporary Employment Agency (INZ). This affected around 40 member companies with around 10,000 employees. The wage level was 40% below what the Bundesverband Zeitarbeit BZA had already negotiated with the DGB . As a result, the BZA did not sign the agreement, but subsequently negotiated wages with the DGB , which in the lowest wage group were a third lower than the statutory minimum wage in the main construction trade . This established low wages in the temporary work sector and the companies began to no longer use temporary workers only to cushion peak orders, but to lay off permanent staff and employ temporary workers on a permanent basis. There was also an increase in the incentives not to directly hire staff made redundant for operational reasons , but only as temporary workers (“ revolving door effect ”). After the number of temporary workers had remained almost unchanged since 2000, it almost tripled between 2003 and 2011.

As a result, the employers 'associations INZ and MVZ merged to form the employers' association of medium-sized personnel service providers (AMP), which continued the collective bargaining partnership with the CGZP. In addition, the CGZP had concluded numerous company collective agreements. There were no collective agreements with the other two employers' associations, the Federal Association of Temporary Employment, Personal Services (BZA) and the Association of German Temporary Employment Companies (iGZ). The Federal Labor Court ruled in several decisions from December 2010 that the CGZP was not eligible for tariffs from the start . The now void collective agreements concluded with the CGZP applied to around 1,600 companies with a total of over 280,000 employees, who now also had a retrospective statutory right to equal pay and equal treatment. The temporary employment agencies had to retrospectively pay the social security contributions for the wage difference of the last four years.

At the joint proposal of BAP, iGZ and the DGB trade unions , the Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs set a generally binding lower wage limit (minimum wage) for temporary work by ordinance pursuant to Section 3a AÜG, which has been binding since January 1, 2012. The minimum wage must also be paid by hirers who are based abroad if they hire temporary workers for work in Germany.

Overview

| October 1960: | The logistics manager Günter Bindan makes itself independent and based in Bremen under his name the first German temporary employment agency. |

| April 4, 1967: | The Federal Constitutional Court declares the extension of the state employment agency monopoly to include commercial temporary employment as unconstitutional and thus enables legal temporary employment by private individuals |

| August 7, 1972: | First regulation of temporary employment in Germany through the passing of the Temporary Employment Act (AÜG) |

| January 1, 1982: | Prohibition of commercial leasing in construction companies for work that is usually performed by workers |

| May 1, 1985: | Extension of the maximum permitted lease period from 3 to 6 months |

| January 1, 1994: | Extension of the maximum permitted lease period from 6 to 9 months |

| April 1, 1997: | Extension of the maximum permitted lease period from 9 to 12 months Approval of the synchronization of initial assignment and employment contract (restriction of the prohibition of synchronization to repeated synchronization) Approval of reinstatement after 3 months of relaxation of the prohibition of time limits |

| January 1, 2002: | Extension of the maximum permitted lease period from 12 to 24 months |

| January 1, 2003: | Elimination of the time limit on the leasing period Elimination of the special prohibition of time limits, the prohibition of reinstatement and the prohibition of synchronization Relaxation of the ban on leasing in the construction industry in the case of leasing between companies in the construction industry Inclusion of the principle of equal pay in the AÜG with an opening clause for collective agreements that deviate from this obligation of the federal government to the detriment of the employee for work, to set up at least one personnel service agency for "placement-oriented temporary employment" in each employment office district |

| February 23, 2003: | Collective bargaining agreement between the Northern Bavarian Temporary Employment Agency (INZ) and the collective bargaining association of the Christian Temporary Employment Unions and PSA (CGZP). This was the first industry-wide collective agreement in the field of temporary employment agencies. The temporary employment industry was only familiar with a few in-house collective agreements, such as the one agreed in 2000 between Randstad and the DAG and ÖTV unions. The conclusion of this collective agreement prevented the principle of “Equal Pay - Equal Treatment” (ie the same payment and treatment as in the hiring company), which would otherwise have applied from January 1, 2004. Up to the aforementioned point in time, the wages and working conditions of temporary workers were not set by collective agreements. |

| May 6, 2003: | Collective agreement between the Mittelstandsvereinigung Zeitarbeit e. V. (MVZ) and the collective bargaining community of the Christian labor unions temporary work and PSA (CGZP) |

| May 29, 2003: | iGZ collective bargaining commission and DGB trade unions sign a wage /, framework /, shell and employment security collective agreement. |

| July 22, 2003: | BZA and DGB unions conclude a general collective agreement. |

| December 31, 2005: | Elimination of the obligation of the Federal Employment Service to set up at least one personnel service agency in each employment office district . |

| April 14, 2011: | The employers' association of medium-sized personnel service providers e. V. (AMP) and Federal Association of Temporary Employment Personnel Services e. V. (BZA) merge to form the "Federal Employers' Association of Personnel Service Providers" (BAP) |

| April 30, 2011: | Entry into force of the legal regulation, which enables the introduction of a generally binding minimum wage ( lower wage limit ) in the field of temporary employment ( § 3a AÜG). |

| Dec. 1, 2011: | Important changes to the AÜG come into effect, including the extension of the scope of the AÜG to non-commercial temporary employment |

| January 1, 2012: | Entry into force of a minimum wage of € 7.89 in the west, € 7.01 in the east based on a statutory ordinance of the BMAS |

| November 1, 2012: | For the first time, temporary workers have to be paid industry surcharges based on a collective agreement if they are assigned to the metal, electrical and chemical industries . The surcharges are staggered in 5 stages according to the leasing period and depending on the pay group between 10% after 6 weeks and 50% after 9 months |

| January 1, 2013: | Industry surcharges in the rubber industry from 4% after six weeks to 16% after nine months. In the plastics industry there are different surcharges, depending on the tariff group. These range in pay groups 1 and 2 from 7% to 25%, in the third and fourth from 4% to 15% and in the fifth from 3% to 10%, but these are also based on the length of work. |

| February 1, 2013: | The BAP (Federal Employers' Association of Personnel Service Providers) terminates the collective agreements with the Christian trade unions |

| April 1, 2013: | Sector surcharges in the rail transport sector , these are also staggered differently according to the duration of use and tariff group. The tariff groups 6 to 9 must also come away empty-handed here. The wood and plastic processing industry has to pay surcharges: from 7% after six weeks and up to 31% after nine months. The textile processing industry also grants surcharges: from 5% after six weeks to 25% after nine months. |

| April 1, 2017 : | Reintroduction of a statutory maximum leasing period of 18 months. Express prohibition of chain leasing . |

After the ban on synchronization (also: ban on synchronization), the employment of an employee is now permitted for just a single leasing to a hirer. The Part-Time and Temporary Employment Act must be observed, a limitation (synchronization) of the assignment on the grounds of “temporary need at the customer” is not permitted according to the case law of the BAG . Thereafter, the employee can be dismissed in compliance with the statutory notice period and in compliance with the Employment Protection Act. The same employee can be re-employed at a later date by lifting the re-employment ban.

Development of the number of employees

The number of temporary workers changed little overall from 2010 to 2014, increased from 2013 to 2015, partly also for statistical reasons (see below), and it fell slightly from 2011 to 2013. Before that, it had risen for years, aided by the deregulation of Agenda 2010 , interrupted only by the effects of the financial crisis in 2009. However, the absolute figures are only of limited significance for the political classification; the ratio to the total number of employees or the ratio in particular would be much more important for new hires. Interestingly, the absolute figures are given a lot of attention in federal politics, s. small request (18/7483) from March 3, 2016 including press coverage.

The following list shows the absolute figures determined by the Federal Employment Agency as of June 30th and December 31st.

(As of March 14, 2016)

| year | June 30th | December 31 | Remarks |

| 1996 | 177.935 | - | - |

| 1997 | 212,664 | - | - |

| 1998 | 252,895 | 232.242 | - |

| 1999 | 286.394 | 286,362 | - |

| 2000 | 339.022 | 337.845 | - |

| 2001 | 357.264 | 302.907 | - |

| 2002 | 326.295 | 308,534 | - |

| 2003 | 327.331 | 327,789 | - |

| 2004 | 399.789 | 389.090 | - |

| 2005 | 453.389 | 464,539 | - |

| 2006 | 598.284 | 631.076 | - |

| 2007 | 731.152 | 721.345 | - |

| 2008 | 794.363 | 673,768 | - |

| 2009 | 609.720 | 632.377 | - |

| 2010 | 806.123 | 823.509 | - |

| 2011 | 909.545 | 871.726 | - |

| 2012 | 908.113 | 822.379 | - |

| 2013 | 851.818 | 814.580 | (according to old statistical data basis) |

| 2013 | 867,535 | 853.215 | (according to the new statistical data basis, see text) |

| 2014 | 912,519 | 883.165 | (Number for June 2014 according to old statistics: approx. 882,000) |

| 2015 | 961.162 | 949.227 | - |

Change in statistics: According to the Federal Employment Agency, the current figures have been recorded as part of a “personal identification of temporary workers” in the “social security notification procedure”. It says in particular: "The changes mean that the number of temporary workers from the new temporary employment statistics (June 2014: 913,000) is around 3.5 percent higher than the number from the previous statistics according to the temporary employment law (882,000)."

A significant part of the temporary work is located in the commercial sector. The unskilled laborers without further details of their activity represented the largest group in December 2012 with 302,178 employees. The service professions followed in second place with 161,953 employees. Men are clearly in the majority when it comes to temporary employment contracts: As of December 31, 2013, only 30% of the employees recorded were women.

According to the Federal Government, an annual average of at least 52,000 employees in the temporary employment sector received top-up unemployment benefit II , including around 43,000 full-time employees (excluding trainees).

In 2019, the media reported that there was an increasing number of temporary work in the care of the elderly , which was particularly attractive for employees because temporary workers were given a say in their work assignments and, for example, they could refuse night and weekend shifts. In addition, temporary workers would be paid better than the permanent staff. According to figures from the Federal Employment Agency (BA), a total of 2% of those employed in nursing were temporary workers in 2018 . The number of temporary workers employed in geriatric care increased from 8,000 to 12,000 between 2014 and 2018. In nursing, the proportion rose from 12,000 to 18,000 temporary workers over the same period. A Federal Council initiative called for a ban on temporary work in the field of care, which u. a. The reason given was to prevent the recruitment of skilled workers by temporary employment agencies.

Permission requirement

In Germany, entrepreneurs who want to operate temporary workers need a permit from the Federal Employment Agency ( Section 1 AÜG). The permit can be refused or revoked if the requirements according to § 3 or § 5 AÜG are met. The permit requirement has also been in effect since December 1, 2011 if the leasing of workers is not commercial within the meaning of trade law, so that, for example, intra-group personnel service companies that lease temporary workers to other group companies at cost price also require a permit.

Temporary employees are exempt from the permit requirement

- between employers in the same branch of industry to avoid short-time work or layoffs, if a collective agreement applicable to the borrower and lender provides for this,

- between group companies within the meaning of Section 18 of the German Stock Corporation Act , if the employee is not hired and employed for the purpose of leasing,

- between employers if the leasing only occurs occasionally and the employee is not hired and employed for the purpose of leasing, or

- abroad if the temporary worker is hired out in a German-foreign joint venture established on the basis of international agreements in which the hirer is involved,

- An employer with fewer than 50 employees who, in order to avoid short-time work or layoffs, hires an employee who is not hired and employed for the purpose of leasing for a period of twelve months, if he has previously notified the Federal Employment Agency in writing of the leasing (PDF ), § 1a Abs. 1 AÜG.

Concealed temporary employment

An unauthorized temporary employment is called a concealed temporary employment. It exists when one or more of the following points are met:

- The lender does not have a permit for temporary employment.

- The actual temporary employment is defined as a work contract to circumvent the social protection of foreign workers.

- The employee activity is declared as self-employed in order to avoid additional wage taxes and formalities under labor law (see bogus self-employment ).

The concealed leasing of employees is illegal, and thus the contracts between the hirer and the lender as well as between the lender and the employee are ineffective ( Section 9 No. 1 AÜG). Instead, an employment contract is faked between the hirer and the employee, whereby both the hirer and the lender are jointly and severally liable for the payment obligations ( Section 10 (1), sentence 1 AÜG).

Principle of equal treatment and exceptions

In Article 5 (1) subpar. 1 of the European Temporary Agency Work Directive , the principle is laid down that the essential terms and conditions of employment of temporary workers during their assignment to a hirer must at least correspond to those that would apply to them if they had been hired directly by the hirer for the same job ( so-called equal pay and equal treatment, Section 9 No. 2 and No. 2a AÜG). However, Article 5 (3) of the Temporary Agency Work Directive contains an opening clause that allows for deviations from the principle of equal treatment to the detriment of temporary workers in collective agreements. This is possible under German law (Section 9 No. 2 AÜG) and has led to the exception being the rule in Germany.

Collective agreements

In Germany there are two valid collective agreements for the temporary work sector that have been concluded between the following collective bargaining parties:

- Federal Employers' Association of Personnel Service Providers V. (BAP) and the DGB trade unions

- Association German temporary employment agency e. V. (iGZ) and the DGB unions

In addition to the remuneration set out in these collective agreements, since November 1, 2012, industry surcharges have been applied between the IG for companies in the metal and electrical industry and the chemical industry, and since January 1, 2013 in the plastics processing industry and in the rubber industry Metall and IG Bergbau, Chemie, Energie and the aforementioned employers' associations have agreed collective agreements on industry surcharges. The rail transport sector, the textile and clothing industry and the wood and plastic processing industry followed on April 1, 2013. The paper, cardboard and plastics processing industry joined them on May 1, 2013. The industry surcharge in the printing industry since July 1, 2013 ends this series for the time being. The amount of the surcharge is staggered and depends on the duration of the assignment with the borrower.

If the employee is hired out for activities for which a minimum wage applies, the temporary employee is to be paid at least this minimum wage in accordance with Section 8 (3) of the Posted Workers Act .

Collective agreements that had been concluded on the employee side by the collective bargaining community of Christian Unions for Temporary Work and Personnel Service Agencies (CGZP) were null and void from the start because the CGZP was not eligible for collective bargaining .

Temporary employment in practice

working time

The collective agreements of the DGB trade unions with the Association of German Temporary Employment Companies (iGZ) and the Federal Association of Temporary Employment Personnel Services (BZA) provide for 35 hours of weekly working time. Through an additional agreement, e.g. B. in the context of a part-time employment, can be deviated from. By deducting public holidays, an "individual regular monthly working time" is formed for each month:

- With 20 working days, the monthly working time is 140 hours.

- With 21 working days, the monthly working time is 147 hours.

- With 22 working days, the monthly working time is 154 hours.

- With 23 working days, the monthly working time is 161 hours.

This corresponds to an average monthly working time of 151.67 hours (35 hours / week * 52/12).

For the temporary worker, however, the working time regulation in the company of the hirer is decisive. Is there z. B. worked 40 hours per week, the temporary worker also has to work 40 hours, but he is only paid 35 hours for the week in question. All hours that are worked beyond the weekly working time of 35 hours are credited to a working time account . Overtime that goes beyond the assumed 40 working hours per week and which the temporary worker may be contractually obliged to do are also credited to the working time account, but the surcharges are paid in the month in which they are incurred. Public holidays are set with the average earnings and the average working hours of the last three months billed in accordance with the iGZ-DGB collective wage agreement, Section 6a. The same applies to the continued payment of wages during vacation and illness.

Working time account

For the leasing company, the working time account is an important element in order to be able to use temporary workers according to the workload in the hiring company. Since the employee has to apply to the employer to reduce the working time account, while overtime can be ordered by the employer, the company mainly benefits from the working time account . This means that time accounts can be built up to a maximum over months, with only the overtime allowance being paid out in each month. The employee only receives the remaining benefit for the hours worked at the time of the later time off or when the hours are paid out at the end of the employment relationship. According to the iGZ tariffs, the working time account may contain up to 150 plus hours and a maximum of 21 minus hours, with the BZA tariffs even 200 plus hours are permitted. Only the hours exceeding 150 plus hours must be insured against insolvency. The number of possible minus hours is not limited here. To safeguard employment , the working time account can even include up to 230 plus hours in individual cases in the event of seasonal fluctuations.

Plus and minus hours

Overtime hours beyond the regular monthly working hours are credited to the working time account as plus hours. Minus hours are deducted from the working time account if the employee has worked less than the regular working time per month. For days on which there is no work with a hirer, the regular daily wage is paid (e.g. for 7 hours at 35 h / week) without any minus hours being transferred to the time account.

The LAG Hessen: judgment of April 28, 2016 - 9 Sa 1287/15 -

Der zwischen dem Bundesarbeitgeberverband der Personaldienstleister e.V. (BAP) - vormals Bundesverband Zeitarbeit Personal-Dienstleistungen e. V. (BZA) - und den Mitgliedsgewerkschaften des DGB abgeschlossene Manteltarifvertrag Zeitarbeit vom 22. Juli 2003 berechtigt den Arbeitgeber nicht, verleihfreie Zeiten (Nichteinsatzzeiten) einseitig als Abzugsposition im Arbeitszeitkonto des Arbeitnehmers zu verbuchen. Diese Zeiten sind keine „Minusstunden“ im Sinne des MTV. Der Arbeitgeber kann die verleihfreie Zeit auch nicht einseitig zur Nichtarbeitszeit (Freizeit) machen.

The basis for this is Section 11 Paragraph 4 Clause 2 and 3 AÜG, which confirms Section 615 Clause 1 BGB for temporary employment. The widespread practice of deducting hours from the temporary worker's working time account for days of non-use is illegal, as the right to remuneration must not be restricted by employment or collective agreements.

Compensation of the working time account

Lt. The IGZ's collective bargaining agreement allows the employer to arrange two working days of time off per month at a date of his choice, if there are enough extra hours available. The temporary worker is also entitled to two freely available working days in compensation, but must apply to the employer for this and have it approved in advance. For urgent operational reasons, he or she can reject the requested time off. If the temporary worker becomes incapable of working for the periods of time off, the hours requested will still be deducted from the working time account.

When the temporary employee leaves, positive working time credit is paid out, negative working time credit is offset against remuneration claims.

Such a set-off does not stand up to judicial review. To this the

LAG Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania:

Judgment of 03/26/2008 - 2 Sa 314/07 - dejure.org

A negative work credit on a work account is not to be compensated by the employee when leaving, despite a corresponding agreement, if the negative credit has arisen due to a lack of work.

The temporary worker can also compensate for a negative time credit through rework. An employment contract can stipulate that a certain amount of overtime is paid every month instead of being credited to the working time account. For this, however, the temporary worker has to pay higher wage tax. A violation of the obligation to continue paying wages (vacation, illness, public holidays) constitutes a so-called refusal (see legal basis) and can lead to the withdrawal of the permit after a report to the state employment office.

Notice periods

The collective agreements provide for relatively short notice periods .

- BZA collective agreement: During the first two weeks of the employment relationship, the notice period between the employer and the temporary worker can be reduced to one day. Thereafter, the employment relationship can be terminated in the first three months of the probationary period with one week's notice. Only after the three months have expired does the statutory notice period of two weeks under Section 622 (3) BGB apply during the remaining probationary period of six months . It should be noted that the short notice periods also apply to temporary employment.

- IGZ collective agreement: In the first four weeks of the probationary period, the employment relationship can be terminated with a notice period of two working days. The notice period is one week from the fifth week to the end of the second month, and two weeks from the third month to the sixth month of the employment relationship. From the seventh month of the employment relationship, the statutory notice periods apply. These statutory notice periods apply on both sides. The probationary period and notice periods apply equally to fixed-term employment.

Social selection

The principles of social selection also apply to the termination of employees at the agency. The temporary workers remain members of the agency's business even during their work with the hirer. The lender may have to replace an employee with one of the other hired workers who are less socially protected. As a rule, he cannot plead that he does not have to make a social selection, because the hirer reserves the right to make a final decision as to which employee should be employed with him. If necessary, the lender must make the social selection before sending the profiles of its employees to other companies when filling positions. In this case, it must send the borrowers the profiles of the more socially protected candidates.

Reward

The remuneration is based on the salary group according to the activity that the temporary worker is to perform (note job description) if the temporary employment agency is bound by a collective agreement. A categorization when hiring requires that the temporary worker actually has the qualification. A later “downgrading” is only possible if it subsequently turns out that the temporary worker is demonstrably unable to provide the service corresponding to the qualification. If the temporary worker is scheduled in a follow-up assignment at a higher qualification level, assignment-related, i.e. H. through an additional agreement to the employment contract, an upgrade can be made for the duration of the assignment.

Some companies reimburse the cost of travel and accommodation, as well as additional meals (also known as "release"). The collective bargaining agreements of the BZA-DGB trade unions allowed cash wages to be converted until mid-2010 : up to 25% of the collective wage could be offset against travel expenses and additional meals.

Example: Standard wage € 7.89 per hour, non-tariff allowance related to the assignment € 0.62, hourly wage therefore € 8.51 per hour, reduction of 25% (for travel expenses, additional meals) to € 6.39 per hour. The temporary worker receives € 8.51 per hour, € 2 of which is fare and additional meals, possibly exempt from tax and social security. After the end of the assignment, however, the temporary worker only receives the collective wage of € 7.89. The additional meal expenses can only be paid out in the first 3 months (non-tariff / regulated by law) of each assignment free of social insurance. This cash conversion is no longer possible since the new agreement came into force on July 1, 2010.

From July 1, 2010, the lowest collective wage (salary group 1) (BZA, iGZ) rose from € 7.38 to € 7.60 in the west and to € 6.65 in the east. From May 1, 2011, the minimum wage increased to € 7.79 and on November 1, 2011 to € 7.89. This was agreed by the DGB trade unions and the employers' association BZA in March 2010. Various clauses that previously allowed falling below the lowest collective wage have been deleted. As part of the changes to the collective agreement of September 17, 2013, the minimum wage was raised to € 8.19 (West) and € 7.50 (East). Further increases took place on January 1, 2014 (€ 8.50 west / € 7.86 east) and on April 1, 2015 (€ 8.80 west / € 8.20 east). From June 2016 it rose to 9.00 (West) and 8.50 euros (East).

In addition to wage increases, the November 2016 collective bargaining agreement is also intended to bring east-west wages into line by April 1, 2021 and a clearer difference to the minimum wage.

| east | west | comment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 07/01/2010 | € 6.65 | 7.60 € | |

| 05/01/2011 | € 6.89 | € 7.79 | |

| 11/01/2011 | € 7.01 | € 7.89 | |

| 11/01/2012 | € 7.50 | € 8.19 | |

| 01/01/2014 | € 7.86 | € 8.50 | |

| 04/01/2015 | € 8.20 | € 8.80 | |

| 06/01/2016 | € 8.50 | € 9.00 | |

| 01/01/2017 | € 8.84 | Adjustment to the general statutory minimum wage | |

| 03/01/2017 | € 8.91 | € 9.23 | |

| 04/01/2018 | € 9.27 | € 9.48 | |

| 01/01/2019 | € 9.49 | ||

| 04/01/2019 | € 9.79 | ||

| October 01, 2019 | € 9.66 | € 9.96 |

When working within the framework of a work contract, the customer cannot necessarily stipulate a collectively agreed remuneration for the contractor - apart from the statutory minimum wage - so that, due to the competitive situation of the temporary employment agencies, the payment can often be worse than in the case of employment within the framework of the temporary employment of the customer . Often the income for comparable activities in the context of temporary work is lower than in a permanent position at the customer.

Continued employment with the borrower

The lender can also act as a recruiter . If the temporary worker is to be permanently employed by the hirer, he will be placed by the lender. For this, the lender can charge a placement fee (usually 10% to 30% of the future gross annual salary) from the new employer. It is also customary to take over the temporary worker free of charge after a specified leasing period, i. d. R. 6 months. This, as well as the amount and due date of remuneration, is regulated in the employee leasing contract (AÜV) in individual contracts. Agreements according to which the temporary worker has to pay a placement fee to the lender are ineffective according to Section 9 (5) AÜG.

Tax law

Temporary workers typically have an external activity in the tax law sense (former term: assignment change activity). This applies even if the employee has worked for a certain hirer for years, because a temporary worker cannot be prepared from the outset that he will be employed with a certain hirer on a permanent basis. Temporary workers can therefore deduct additional expenses for trips to the hirer's business premises and for their meals in the amount of certain lump sums as income-related expenses from their taxable income. However, subsistence costs are only deductible for three months per deployment location ( Section 9 (4a ) of the Income Tax Act ). Compensation paid by the employer for travel expenses and meals is tax-free, provided that it does not exceed the expenses that can be deducted as income-related expenses according to Section 9 of the Income Tax Act.

Political Debate in Germany

While the FDP and CDU / CSU advocate temporary work in its current form in Germany, the Left Party rejects temporary work. The SPD and Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen, on the other hand, want to hold on to temporary work, but abuses are to be ended there and the implementation of equal working conditions and equal pay for permanent staff and temporary workers should be achieved. They achieved this with the new regulation of temporary work and work contracts, which the Bundestag passed on Friday, October 21, 2016 with the votes of the Union and the SPD. The change in law came into force on April 1, 2017.

Work contracts as a substitute for temporary work

On December 14, 2010, the Federal Labor Court declared all collective agreements negotiated by the collective bargaining community of Christian Unions for Temporary Work and Personnel Service Agencies (CGZP) since 2003 in the context of temporary employment to be invalid. With the decision, the court gave temporary workers the opportunity to sue for the same wages for the same work . After this court ruling, Siemens' interest shifted from using temporary workers back to concluding work contracts . This enables Siemens to bypass the works council in the case of co-determination rights. Since the end of 2011, this change in strategy has been accompanied by a broad political debate about the “abuse” of contracts for work and services. What is new about this development is that work contracts are no longer just a matter of multiple disadvantaged groups of employees ( unskilled , women or migrants ), but are also finding their way into core areas of industrial production that for a long time were considered by the public to be relatively well protected "high-wage sectors".

The market for temporary work and personnel services in Germany

Temporary employment is represented in all branches of the economy and with all qualifications . According to Section 1b AÜG, there is a sectoral ban on the provision of commercial workers in companies in the construction industry .

The German agency and temporary employment market is highly fragmented. There are just over 11,500 temporary employment agencies in Germany, which employ around 2% of the working population. This corresponds to around 900,000 temporary workers (November 2010). According to the World Association of Temporary Employment (CIETT), it is around 2.5% in the Netherlands , around 5% in the UK and around 2.1% in France .

In Germany, the domestic sales of the five largest personnel service providers in 2006 were over 3.2 billion euros. The industry giants Randstad , Adecco , Persona service and Manpower share around 30% of the market.

In 2013, the following providers largely determined the German market for temporary employment:

| rank | Companies | Sales in Germany in million euros | Number of temporary workers in Germany |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Randstad Germany 1) | 1,949.3 | 55,000 |

| 2 | Adecco Germany 2) | 1,629.3 | 37,300 |

| 3 | Persona Service Verwaltungs AG | 709.5 | 19,000 |

| 4th | Autovision temporary work 4) *) | 618.0 | 11,200 |

| 5 | ManpowerGroup Germany 3) | 590.2 | 19,958 |

| 6th | IK Hofmann | 578.0 | 17.114 |

| 7th | Dekra work | 318.0 | 8,743 |

| 8th | 7S Group | 294.5 | 7,261 |

| 9 | ZAG temporary employment company | 270.0 | 10,000 |

| 10 | Orizon | 261.6 | 7.139 |

- *) Data partially estimated

- 1) Revenues including Gulp, Randstad Financial Services, Randstad Outsourcing, Randstad Professionals, Randstad Sourceright and Tempo-Team Personnel Services.

- 2) Revenues of the Adecco Group companies in 2014: Adecco Personaldienstleistungen GmbH: € 511.8 million, DIS AG: € 491.4 million, Tuja Group: € 626.1 million

- 3) Including sales of Vivento IS, the joint ventures Bankpower and AviationPower as well as other subsidiaries

- 4) Changes in the internal employee structure as a result of the transfer of the company on January 1, 2014. Before that, the number of temporary workers at Autovision GmbH and Wolfsburg AG

Until mid-2012 there was a continuously high demand for temporary workers, then the decline in gross domestic product (GDP) from 3.0 percent (2011) to 0.7 percent caused a decline in sales for some companies and the introduction of industry surcharges Decline in profits. As early as the 2000s, new business-to-business services in the area of recruiting or the outsourcing of entire business processes were created . If the coordinating activities also take place in the client's premises, this is called on-site management ; A personnel service provider, as a so-called master vendor, can distribute the personnel requirements to other personnel companies. Companies with an extensive need for temporary workers who are provided by several companies are now making use of the "Managed Service Providing" service, in which a temporary employment agency primarily acts as an organizer of the temporary workers required, compares offers and deployment concepts and, so to speak, acts as the hiring company Consultant is available for optimized use. The general acceptance of the industry is also reflected in the recognition of an independent occupational profile in accordance with the Vocational Training Act (BBiG), with the training course "clerk for personnel services".

Temporary employment in Austria

The supply of labor to third parties governs Personnel Leasing Act (AÜG) of 1988. The charge relating to the employee during the transfer, has become the collective agreement to align provisions of the Staff term industry. The employee must not be “worse off” than the permanent staff.

Austrian definitions (according to AÜG):

-

§ 3. (1) The provision of workers is the provision of workers for work to third parties.

- (2) The subcontractor is whoever contractually obliges workers to perform work on third parties.

- (3) Employer is someone who uses temporary workers to perform work for in-house tasks.

A transfer to striking companies is prohibited by law (§ 9 AÜG).

Figures on temporary employment in Austria

The Federal Ministry of Economics and Labor collects annual statistical data on temporary employment. As of July 29, 2005, there were a total of 46,679 leased employees with 12,300 employees. Of these 46,679 employees, 9,670 (20.7%) were hired for up to one month and 12,385 (26.5%) for 12 months. 50.5% of the employees were left for up to 6 months, 40.4% for 6 months.

As of July 31, 2010, there were a total of 66,054 leased employees with 2,082 employees.

Temporary employment in Switzerland

In Switzerland, the provision of workers is regulated in the Employment Placement Act (AVG). Instead of temporary work and temporary workers, the terms temporary work and temporary workers are used. Temporary workers are employed at the same wages as permanent employees. If an industry has a collective labor agreement (GAV), the wages contained therein apply. If there is no collective agreement, the wages customary for the location and the industry must be paid. In general, temporary work has a better reputation in Switzerland than in neighboring countries. The main reason for this is the lack of “ general suspicion ”: In Switzerland there is no legal protection against dismissal and there are far fewer restrictions on fixed-term employment contracts; temporary agency work is therefore not suspected of attempting to circumvent such regulations. In addition, the collective employment contract for personnel leasing (GAV) provides for 1% of the total wages to be paid into an education fund, from which the temporary worker receives further training measures after a certain period of employment.

Lenders who break the law can expect heavy fines and / or the withdrawal of their license.

Temporary employment in the Netherlands

In the Netherlands, for example, there is “Werkland”, a temporary employment agency in Rotterdam for those who are particularly difficult to place. She pays the minimum wage and receives money from the city - instead of social assistance that goes directly to those affected.

criticism

Social problems

The union side argues that fewer temporary jobs are created than regular jobs are being replaced, as employers can use workers more efficiently. This thesis is controversial. On the other hand, it is undisputed that temporary work will lower the general wage level. However, one should note here that 1.8% of all employees in Germany are employed as temporary workers. Temporary workers form an ever-increasing part of the so-called top - ups , those workers who are dependent on state benefits despite full-time employment.

Social problems

Many employees suffer from their role as external workers, as they are only insufficiently integrated into the social structure of the user company. Causes for this include a. the time limit and the competitive behavior of regular employees who, for example, are afraid of being replaced by external workers. In many cases, the operational integration of temporary workers is even deliberately prevented by the line manager . In some companies it is common to give temporary workers different colored work clothes and not to provide a changing room in order to make them aware of their lower status and to prevent their integration into the hiring company. Invitations to external events such as Christmas parties are a rarity. It was also reported that conversations with permanent employees “are not welcome” and conversations with temporary workers about the company situation constitute grounds for termination without notice . It also happens that certain privileges such as discounts in company canteens are not granted. The changing locations limit the possibility of social relationships .

The financial crisis that began in 2007 exacerbated the differences between employees in precarious employment relationships and permanent employees .

Problems in the borrower's company

Due to the limited working hours, temporary workers only identify with the company to a limited extent. They also have to be trained for the job and do not have the same routine as regular workers. Also, contrary to the often propagated sticking effect , temporary work actually rarely proves to be a stepping stone into a regular job. According to an IAB study, only a small proportion of previously unemployed people succeed in making the move from temporary work to conventional employment for a period of two years after being hired out. Instead of a takeover rate of around 30%, a value of 7% is now considered realistic.

Other disadvantages for temporary workers

According to an IAB study from 2011, temporary workers earn on average between 20 and 25 percent less than regular employees for the same work. A few cases are known in the media in which temporary employment agencies systematically and sometimes unnoticed breach employment and collective bargaining agreements by employees. For example, some cases of wage dumping are known where the relatively low minimum wage of 7.80 euros, which was decided by the unions of the German Federation of Trade Unions with the temporary employment agencies, is well undercut. The then Federal Labor Minister Ursula von der Leyen criticized the possible abuse of temporary work to lower wages. According to this, some companies use temporary work to permanently reduce wage costs for employees. She emphasized that it was unacceptable for employees of temporary employment agencies to get lower wages for the same work in the long term. It became known, for example, that the Schlecker discounter , after some branches were closed, hired a number of saleswomen through an affiliated rental company at significantly worse terms in newly opened shops. Similar cases are currently cropping up in the freight forwarding business and in the elderly care and waste management sectors . It is also criticized that the responsible Federal Employment Agency has inadequate controls on temporary employment agencies. The continuous qualified in-company training and further education by the actual employer often does not take place sufficiently during the assignment, so that later dismissals due to lack of employment and insufficient qualification of the employee with subsequent unemployment due to lack of professional skills can occur.

Differentiation from the contract for work and services

In the case of a contract for work and services , a third-party deployment of personnel can also occur, in that the contractor performs the promised work with his own employees in the customer's company. In contrast to a lender, however, the contractor determines the type and sequence of the work himself and he assigns the work himself. Its employees are not organizationally integrated into the work processes or the production process of the ordering company. In contrast to temporary employment, the right to issue instructions for employees working in the customer's company remains with the employer, who as a contractor also bears the entrepreneurial risk and the warranty obligation. The service contract procedure is also used for rack jobbing .

Differentiation from the agency principle

In contrast to the employer principle in Germany, in which the personnel service provider takes care of all employer obligations and risks, such as B. assumes the continued payment of wages when not employed, employees in other countries z. B. in France often deployed or mediated according to the agency principle. Neither protection against dismissal nor continued payment of wages apply, but the employees deployed receive at least the same wages as the employees in the companies in which they are deployed.

See also

literature

- Seigis, M. Christian: Temporary workers in the social offside - temporary employment in Germany . Tectum Verlag, Marburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-8288-2679-3 .

- Ricarda C. Bouncke: The new role of temporary work in Germany . R. Hampp, Mehring 2012.

- Ulrich Bretschneider: Calculation in temporary work . Aumann, Coburg 2011

- Marijan Misetic: “Generation 50plus and temporary work”. Facts and practical experience . Edition Aumann, 2011, ISBN 978-3-942230-70-4 .

- Sonja Elghahwagi: temporary employment. Basics, development, goals. Vdm Verlag Dr. Müller, 2006, ISBN 3-86550-155-9 .

- Marc A. Fischer: Critical evaluation of temporary work . GRIN Verlag , 2013, ISBN 978-3-656-40300-5 .

- Anke Freckmann: temporary employment. 2nd Edition. Verlag Recht und Wirtschaft, 2005, ISBN 3-8005-4221-8 .

- Joachim Gutmann, Martina Kollig: Temporary work. How to optimize the use of personnel. Verlag Haufe, Freiburg 2004, ISBN 3-448-06201-4 .

- Joachim Gutmann, Stefan Kilian: Temporary work. 2nd Edition. Haufe, Freiburg / Brsg. 2011.

- Steffen Hillebrecht: Management of personnel service companies. 2nd Edition. Wiesbaden 2014, ISBN 978-3-658-05884-5 .

- Rainer Moitz: Handbook for personnel service clerks . 3. Edition. VRPM, Troisdorf 2013.

- Wolfram Wassermann, Wolfgang Rudolph: Temporary work as an object of employee participation . Working paper 148, Hans Boeckler Foundation. boeckler.de (PDF; 543 kB)

- Wolfgang Ochel: Hartz and more - To reduce unemployment through temporary work. In: ifo Schnelldienst . 2003-2056. Vintage. cesifo-group.de (PDF)

- Markus-Oliver Schwaab , Ariane Durian: Temporary work - opportunities - experiences - challenges . Gabler Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-8349-1277-0 .

- Marc Tobias Rosenau, Ulrich Mosch: New regulations for temporary work. In: NJW -Special. 08/2011, 242

- Guido Zeppenfeld, Holger Faust: Temporary work according to the CGZP decision of the BAG. In: NJW . 23/2011, 1643

- Ricardo Büttner , Stefan Pennartz: Electronic job market platform: Perspectives in temporary work, labor and labor law . 66 (5), May 2011, pp. 292-293.

TV talk shows and reports

- on the matter of Baden-Württemberg !: Temporary work at Amazon and Co - curse or blessing? , with Ariane Durian (Chairwoman of the Association of German Temporary Employment Companies ), SWR , 17:47 min., German first broadcast on February 28, 2013 at 8:15 pm on SWR television in Baden-Württemberg .

- “The Federal Employment Agency is increasingly placing unemployed people in temporary work - good for the statistics, but not always good for job seekers. Placement rates and a booming temporary employment industry are fueling this development. ”Plusminus, broadcast on March 13, 2012.

- Temporary agency workers tricked: the total failure of the Federal Employment Agency . ( Memento from July 7, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Monitor, broadcast on July 4, 2013.

Web links

- Link catalog on the subject of temporary employment at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Information from the Federal Employment Agency 2007/2008 on the subject of temporary work to download as PDF ( memento from October 31, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Further information on the rights and obligations of temporary workers in Austria

- Thomas Blanke: What changes to the German law does the implementation of the EU directive on temporary work require - with a focus on the principle of equal treatment and deviations in accordance with Art. 5 of the EU Directive? Legal opinion on behalf of the DGB, April 2010.

- Hajo Holst, Oliver Nachtwey, Klaus Dörre: Functional change in temporary work. 2009 study . (PDF; 2.6 MB) Otto Brenner Foundation, archived from the original onJanuary 22, 2013.

Individual evidence

- ↑ IFO Schnelldienst 1/2003 - 56th year, p. 3 Fig. 1

- ↑ see also S. Hillebrecht: Management of personnel services. Wiesbaden 2014, p. 102ff., More detailed U. Brettschneider: Calculation in temporary work. Coburg 2010.

- ^ S. Hillebrecht: Management of personnel service companies . Wiesbaden 2014, p. 104.

- ↑ Federal Government: Answer of the Federal Government to Small Inquiry - Printed matter 19/4046 . Ed .: German Bundestag. Berlin August 27, 2018, p. 26 ( bundestag.de [PDF] table for question 7: Number of registered jobs according to selected characteristics).

- ^ Foundation of the Günter Bindan company

- ↑ Roman Milenski: temporary - opportunity or precariousness? GRIN Verlag, 2010, p. 22.

- ↑ Ansgar Mayer: Small, cheeky and very clever. In: The time. May 22, 2003.

- ^ Peter Thelen: Judges declare collective agreements on temporary work to be ineffective. In: Handelsblatt . December 8, 2009, accessed July 31, 2013.

- ^ First collective agreements for temporary work , SoZ , May 2003, p. 5, accessed on July 31, 2013.

- ^ Christian Plöger: IG Metall defames unpleasant competition , impulse.de from February 26, 2003, accessed on July 31, 2013.

- ↑ Temporary work: Every third position for temporary workers ( Memento from January 4, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) ingenieur.de from July 30, 2010, accessed on July 31, 2013.

- ↑ Horst Gobrecht: Equal pay for equal work - and bye! , dkp-online.de of June 13, 2003, accessed on July 31, 2013.

- ↑ DGB welcomes collective agreement on temporary work , AP report on faz.net from May 28, 2013, accessed on July 31, 2013.

- ↑ Von der Leyen wants to take action against abuse. In: Handelsblatt . March 25, 2012, accessed August 1, 2013.

- ↑ Karin Finkenzeller: For a few euros less , Die Zeit from October 15, 2010, accessed on August 1, 2013.

- ↑ a b Federal Labor Court, decision of December 14, 2010, 1 ABR 19/10

- ↑ a b Landesarbeitsgericht Berlin-Brandenburg, decision of January 9, 2012, 24 TaBv 1285/11

- ↑ a b Federal Labor Court, decision of July 24, 2012, 1 AZB 47/11, paragraph 12

- ↑ Stefan Schulte: Many temporary employment agencies are threatened with bankruptcy. The West, December 14, 2010, accessed December 14, 2010 .

- ↑ Annelie Buntenbach, Invalid dumping tariffs in temporary work: employers threaten back payments of wages and social contributions, SozSich 2010, 110f.

- ^ German statutory accident insurance: Top social insurance organizations on the incapacity of the CGZP ( Memento of May 24, 2011 in the Internet Archive ). Press release of March 18, 2011. Accessed March 18, 2011.

- ↑ a b First ordinance on a lower wage limit in temporary employment

- ^ Foundation of the Günter Bindan company

- ↑ Rainer Bindan: My father the temporary work pioneer. ( Memento from May 17, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF)

- ↑ BVerfG, judgment of April 4, 1967, Az. 1 BvR 84/65, BVerfGE 21, 261 .

- ↑ Employee Leasing Act of August 7, 1972, Federal Law Gazette I, p. 1393.

- ↑ Art. 1 § 1 No. 2 of the law on the consolidation of employment promotion (Arbeitsförderungs-Konsolidierungsgesetz - AFKG -) of December 22, 1981 ( Federal Law Gazette I, p. 1497 ).

- ↑ Art. 8 Para. 1 No. 2 of the Employment Promotion Act 1985 (BeschFG 1985) of April 26, 1985 ( Federal Law Gazette I, p. 710, 715 ).

- ↑ Art. 2 No. 1d of the First Law for the Implementation of the Savings, Consolidation and Growth Program (1. SKWPG) of December 21, 1993 ( Federal Law Gazette I, pp. 2353, 2362 ).

- ↑ Art. 63 No. 7 of the Employment Promotion Reform Act (Arbeitsförderungs-Reformgesetz - AFRG) of March 24, 1997 ( Federal Law Gazette I p. 594, 714 ).

- ↑ Art. 7 No. 1 of the law on the reform of labor market policy instruments (JobAQTIVGesetz) of December 10, 2001 ( Federal Law Gazette I p. 3443, 3463 ).

- ↑ Art. 6 of the First Law for Modern Services on the Labor Market of December 23, 2002 ( Federal Law Gazette I p. 4607, 4617 ); ( Hartz I )

- ↑ Art. 1 No. 6 of the First Law for Modern Services on the Labor Market of December 23, 2002 ( Federal Law Gazette I p. 4607, 4609 ).

- ↑ Amendment to § 37c SGB III

- ↑ BAP press release

- ↑ a b Article 1 of the First Act to amend the Temporary Employment Act - Prevention of abuse of temporary employment

- ↑ On August 8, 2011, the BMAS collective bargaining committee unanimously approved the proposal by BAP, iGZ and DGB unions. The Federal Cabinet passed a resolution on the relevant ordinance on December 13, 2011. Comes into force on January 1, 2012 Press report , BAP press release on December 8, 2011.

- ↑ Collective agreement on branch surcharges for temporary workers in the metal and electrical industry of March 22, 2012 between IG Metall, BPA and IGZ

- ↑ Sector surcharges in the chemical industry

- ↑ Temporary employment tariffs with surcharges for the metal and electrical industry (PDF; 151 kB)

- ↑ Temporary employment in the chemical industry

- ↑ Sector surcharges in the rubber industry

- ↑ ( page no longer available , search in web archives )

- ↑ Termination of collective agreements with Christian trade unions ( Memento from April 12, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Sector surcharges in rail transport (PDF; 671 kB)

- ↑ Surcharges in the textile and clothing industry (PDF; 565 kB)

- ↑ Changes to the AÜG from April 1, 2017

- ↑ Oliver Hahn in DATEV magazine : Ban on leasing chains, monthly issue 06/2017, loaded on March 16, 2018.

- ↑ bundestag.de

- ↑ Temporary employment. In: statistik.arbeitsagentur.de. Retrieved September 26, 2019 .

- ↑ Graphic: Development of temporary work , from: Numbers and facts: The social situation in Germany , online offer of the Federal Agency for Civic Education / bpb (2008)

- ↑ Method report of the statistics of the Federal Employment Agency (PDF)

- ↑ Answer of the Federal Government of August 29, 2012 to a small request from MPs Beate Müller-Gemmeke and others, Bundestag printed matter 17/10473 (PDF; 113 kB), p. 6.

- ↑ Temporary work in nursing - light or shadow? In: Careloop. August 6, 2020, accessed on August 7, 2020 (German).

- ↑ Tina Groll: Last way out, temporary work. In: zeit.de. November 26, 2019, accessed November 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Hannes Heine: Senator Kalayci wants to ban temporary work in nursing. In: tagesspiegel.de. October 28, 2019, accessed November 30, 2019 .

- ↑ The scope of the AÜG has been expanded by the First Act amending the Temporary Employment Act - Prevention of abuse of temporary employment

- ↑ justiz.nrw.de LAG Baden-Württemberg · Judgment of December 3, 2014 · Az. 4 Sa 41/14

- ↑ Collective agreement on industry supplements for temporary workers in the metal and electrical industry of March 22, 2012.

- ↑ Collective agreement on industry supplements for temporary workers in the chemical industry ( Memento of December 12, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 3.5 MB)

- ↑ Collective agreement on industry surcharges for temporary workers in the plastics processing industry ( Memento of October 23, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 182 kB)

- ↑ Collective agreement on industry supplements in the rubber industry ( Memento from October 23, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 183 kB)

- ↑ BZA / DGB collective agreement. ( Memento from January 17, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 243 kB)

- ↑ General collective agreement for temporary work , on dgb.de, accessed on October 13, 2018.

- ↑ Federal Labor Court, judgment of June 20, 2013, 2 AZR 271/12, paragraph 19

- ↑ Lübeck Labor Court, judgment of September 4, 2013; Az. 5 Ca 1244/13; Labor law decisions 04/2013, p. 167.

- ^ Eva Roth: Two new collective agreements agreed - wage increase in temporary work. In: fr.de. March 10, 2010, accessed September 19, 2019 .

- ^ Eva Roth: Commentary on collective agreements ( Memento from August 4, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) In: Frankfurter Rundschau. March 10, 2010.

- ↑ BAP / DGB collective bargaining agreement ( Memento from February 10, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (personaldienstleister.de, PDF)

- ↑ Tariff information for temporary work / agency work with tariff table and pay groups. (No longer available online.) DGB Federal Board, archived from the original on January 9, 2017 ; accessed on January 9, 2017 .

- ^ Judgment of the Federal Fiscal Court of June 17, 2010, VI R 35/08

- ↑ Michael Schlecht: Stop wage dumping through temporary work. In: die-linke.de. March 22, 2011, accessed May 26, 2019 .

- ↑ Green delegates booing Palmer's temporary work plans away , n-tv

- ↑ SPD wants to curb abuse in temporary work , Bundestag.de

- ^ Claudia Heine: German Bundestag - New regulations on contracts for work and temporary work decided. Retrieved March 26, 2019 .

- ↑ CGZP collective agreements for temporary work invalid: Information for employees on dgb.de, May 31, 2011.

- ↑ Siemens leverages temporary work agreement from Gudrun Bayer on nordbayern.de , as of March 29, 2010.

- ↑ Contracts for work and services - it can be even cheaper “The rules for temporary work have become stricter. Companies from trade and industry know how to bypass them. ”By Massimo Bognanni and Johannes Pennekamp on zeit.de , as of December 8, 2011.

- ↑ Participation in the use of work contractors - works council and work contracts. In: dgb.de October 7, 2013, accessed on July 15, 2020.

- ↑ Position paper of the DGB Federal Executive Committee against the improper use of contracts for work and services ( PDF , 66 kB), as of December 30, 2013.

- ^ Philipp Lorig: Work contracts - The new wage dumping strategy ?! Study on behalf of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. Berlin 2012, pp. 5-6.

- ↑ It is permitted between companies in the construction industry and other companies if these companies determine this by collective agreements that have been declared generally binding, or between companies in the construction industry if the leasing company has demonstrably been covered by the same framework and social security collective agreements for at least three years or their generally binding nature becomes. “Construction business” within the meaning of § 1b AÜG are companies that are listed in § 1 of the Construction Ordinance, but not for companies within the meaning of the negative catalog according to § 2 BaubetrV.

- ↑ OLG Dresden, decision of January 27, 2003 , Az.Ss (OWi) 412/02

- ↑ IW study on temporary employment. (PDF; 2 MB)

- ↑ Lünendonk - Leading temporary employment and personnel service companies in Germany 2010. (PDF; 201 kB)

- ↑ Lünendonk List 2015 "Leading Temporary Employment and Personnel Service Companies in Germany" (PDF)

- ↑ Lünendonk topic dossier "Sector surcharge tariffs are changing temporary work in Germany" (PDF; 3.5 MB)

- ^ Reference to on-site management activity since 2003 on franz-.wach.de, accessed on September 17, 2019.

- ↑ Note on master vendor activity since 2007 on franz-.wach.de, accessed on September 17, 2019.

- ↑ On-Site-Management / Master-Vendor-Contract on haufe.de, accessed on April 17, 2014.

- ^ S. Hillebrecht: Management of personnel service companies . Wiesbaden, 2014, p. 83.

- ^ S. Hillebrecht: Management of personnel service companies . Wiesbaden 2014, p. 83.

- ↑ see Rainer Moitz: Handbook for personnel service salespeople, Troisdorf 2013, Johannes Beste u. a .: Personnel services clerks, 1st year of training, Cologne: Bildungsverlag eins 2012.

- ↑ Survey on the reference date of temporary employment. (PDF; 31 kB) (No longer available online.) Bmask.gv.at, archived from the original on January 31, 2012 ; Retrieved August 18, 2011 .

- ↑ Commercial labor leasing in Austria in 2010. (PDF; 45.4 kB) In: akupav.eipi.at. Archived from the original on January 31, 2012 ; accessed on April 14, 2019 .

- ^ S. Hillebrecht: Management of personnel service companies . Wiesbaden 2014, p. 106.

- ↑ Andreas Ross: Unemployed in Rotterdam - Anyone can do something. In: faz.net . February 15, 2010, accessed August 10, 2020.

- ↑ Markus Breitscheidel: Poor through work. An undercover report. Econ, Berlin 2008.

- ↑ Johannes Giesecke, Philip Wotschack: Flexibility in times of crisis: losers are young and low-skilled employees. WZB 2009, WZBrief work June 2009

- ↑ Ulrike Meyer-Timpe: Temporary work: worker on call . In: Die Zeit No. 18, April 26, 2007, p. 23.

- ↑ Tobias Schormann: Temporary work - using the "sticking effect" . In: Hamburger Abendblatt, August 17, 2010.

- ↑ Karin Finkenzeller: Temporary Workers: For a few euros less . In: Die Zeit No. 42, October 14, 2010.

- ↑ Labor market: what is the pay? In: focus.de . February 24, 2011, accessed February 28, 2020.

- ↑ Temporary work: 2.71 euros wages: "This is slavery" , Süddeutsche.de

- ↑ Life as a temporary worker: If the probationary period lasts forever , Spiegel Online

- ↑ Temporary work: Von der Leyen wants to take action against abuse , handelsblatt.com

- ^ Wage dumping with temporary work: The Schlecker Principle Stern.de

- ↑ wage dumping in temporary workers: Boom business hours working out of control , Süddeutsche.de

- ↑ Questionable quota: why job centers push temporary work . Plusminus, broadcast on March 13, 2013, online at mediathek.daserste.de.