Non-voters

A non-voter is a person who is entitled to vote and who does not actively participate in political elections . The term is used in common parlance and media coverage in connection with political elections. Not voting is only sanctioned in countries where voting is compulsory .

phenomenon

Non-voters in Germany

The turnout in Germany has fallen sharply differ on average since 1949 at all levels of the political system. The proportion of non-voters in local , regional, state parliament and European elections is strikingly high . In the European elections, the proportion of non-voters increased from 34.3% in 1979 to 57.0% (2004 European elections); in federal elections it even more than tripled, from 8.9% (1972) to 29.2% (2009).

| Political level | Period | Minimum (x) (year) | Maximum (x) (year) | Graphic representation (values in percent of all eligible voters) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

European elections

|

1979 to 2019 | 34.3% (1979) | 57.0% (2004) | |

Bundestag elections |

1949 to 2017 | 8.9% (1972) | 29.2% (2009) | |

State elections in Baden-Württemberg

|

1952 to 2016 | 20.0% (1972) | 46.6% (2006) | |

State elections Bavaria

|

1946 to 2018 | 17.7% (1954) | 42.9% (2003) | |

Elections to the Berlin House of Representatives

|

1946 to 2016 | 7.1% (1958) | 42.0% (2006) | |

Brandenburg state elections

|

1990 to 2019 | 32.9% (1990) | 52.1% (2014) | |

Citizenship elections Bremen

|

1947 to 2019 | 16.0% (1955) | 49.8% (2015) | |

Hamburg state elections

|

1946 to 2015 | 16.0% (1982b) | 43.1% (2015) | |

State elections in Hesse

|

1946 to 2018 | 12.3% (1978) | 39.0% (2009) | |

State elections for Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania

|

1990 to 2016 | 20.6% (1998) | 48.5% (2011) | |

State elections Lower Saxony

|

1947 to 2017 | 15.6% (1974) | 42.9% (2008) | |

State elections for North Rhine-Westphalia

|

1950 to 2017 | 13.9% (1975) | 43.3% (2000) | |

State elections for Rhineland-Palatinate

|

1947 to 2016 | 9.6% (1983) | 41.8% (2006) | |

State elections Saarland

|

1947 to 2017 | 4.3% (1947) | 44.5% (2004) | |

State elections of Saxony

|

1990 to 2019 | 27.2% (1990) | 50.8% (2014) | |

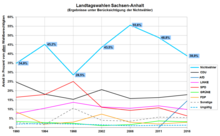

State elections for Saxony-Anhalt

|

1990 to 2016 | 28.5% (1998) | 55.6% (2006) | |

State elections for Schleswig-Holstein

|

1947 to 2017 | 15.2% (1983) | 39.9% (2012) | |

State elections Thuringia

|

1990 to 2019 | 25.2% (1994) | 47.3% (2014) | |

| (×) Proportion of non-voters in relation to all eligible voters | ||||

Non-voters in other countries

The situation in Austria can be compared to Germany. Here the percentage of non-voters in the National Council elections rose from around 9 percent in 1979 to around 21 percent in 2008.

The number of non-voters in Switzerland is significantly higher than in Germany and has been over 50 percent of all eligible voters in the National Council elections since 1979.

In France, in the so-called “banlieues” in the regional elections, non-participation has reached a rate of up to 70 percent, which is seen as an indication of the disintegration not only of the electorate but of society.

In the USA, non-voters have been well over 50 percent of all eligible voters for decades.

Possible effects

If an election is viewed as a single event, the proportion of non-voters has no discernible effect on the election result, unless changing the voter turnout or the absolute number of votes to overcome a threshold clause. If, on the other hand, one considers the migration of voters to the camp of non-voters in comparison to the last election , conclusions can be drawn in certain cases about the influence of non-voters.

According to the electoral law in force in practically all countries, mandates or seats are allocated on the basis of the valid votes cast . Failure to participate in elections reduces the reference base (valid votes) to which the relative share of a party refers. According to the rules of fractions, the denominator is initially smaller. In particular, parties with a stable core electorate benefit from the constant numerator (number of votes) in the fraction calculation.

Example 1:

Assume that party X has an almost stable voter potential of 95,000 votes. The number of valid votes cast is initially 2,000,000. Party X thus achieved 4.75% and failed because of the 5% clause.

In the next election, the number of non-voters increases. As a result, the number of valid votes cast drops to 1,800,000. Party X also loses slightly, but remains fairly stable with a total of 91,000 votes. Due to the reduced reference base, it now reaches 5.06% of the valid votes and passes the 5% hurdle.

Example 2:

In the last election, parties A and B each received 46% of the valid 2,000,000 votes. Thus, each of the two parties received 920,000 votes.

In the next election with 1,800,000 valid votes, Party A loses massively and only reaches 756,000 votes. Party B remains relatively constant and gets 918,000 votes. The percentage share of party A sinks to 42% of the valid votes while party B, despite the almost constant number of votes, achieved an absolute majority with 51%.

Example 3:

If the voters of all parties A, B and X migrate to the camp of non-voters, the effect depends on how the shares are distributed among the parties. If everyone loses the same amount, for example 20,000 votes, party X is of course at the greatest disadvantage. If, however, everyone loses the same percentage by emigration to the non-voters, this does not change the majority.

In practice there are always significant changes in the proportion of non-voters. The drastic increase in the proportion of non-voters in the Bavarian state elections in 2003 compared to 1998 contributed significantly to the fact that the CSU won a two-thirds majority of seats despite its own loss of votes. In the state elections in Baden-Württemberg in 2011 , a significant decrease in the number of non-voters compared to the previous election contributed significantly to a change in power.

Types of non-voters

The division into types of non-voters differs depending on the author. Oskar Niedermayer divides the non-voters into four groups:

- the disinterested

- the rational ones

- the protest voters

- the "technical" non-voters

According to Karl-Rudolf Korte , the discussion about the reasons for the rise in non-voters is by no means resolved. From the perspective of the increasing delegitimisation of the entire political system (see crisis thesis below), the following causes are mentioned:

- Disenchantment with parties and politics

- Dissatisfaction with the political system

- social and economic dissatisfaction

From the opposite point of view (normalization thesis, see below), increasing satisfaction is a cause of the increasing number of non-voters. A cautious division into types of non-voters is:

- disgruntled, dissatisfied non-voters

- politically unaffected non-voters

According to Thomas Kleinhenz, there is much to be said for the effect of period effects. He divides the non-voters into seven groups:

- the "marginalized"

- the "disinterested passive"

- the " sated "

- the "advancement-oriented younger"

- the "young individualist "

- the "politically active"

- the "disappointed worker"

In summary it can be said:

The largest group of non-voters is the rational , economic or periodic non -voters. According to an explanatory approach based on the premises of the rational voter , non-voters in this group only abstain from voting in individual elections and decide, depending on the situation, from election to election whether they want to participate or not - depending on the importance of the election after a cost. Weighing up benefits ( Bundestag elections, for example, much higher than European elections ). According to social psychological interpretations, they are mostly satisfied with the system, have little or no party affiliation and generally tend to change voting behavior due to cognitive dissonances . The economic non-voters are at the center of the scientific interest of electoral research.

Another group are the general non-voters who, for very different reasons, either participate in several elections in a row or never in political elections. This includes citizens who do not vote for structural opposition to the political system or for religious reasons. B. Jehovah's Witnesses (see section Relationship with the State ) or the Christadelphians . With them, not participating is a conscious decision. Their number is estimated to be very few. The basic non-voters also include all those who never cast their vote due to a lack of political interest and great distance from the political institutions. After the very weak turnout in the state elections in Saxony (August 31, 2014), Tom Strohschneider generally spoke of “Democrats on the sofa”.

Likewise, there are people who do not vote because their vote is only one of several million votes. They do not vote because they believe that their vote has no weight and therefore has no significant influence on the election result.

The avowed non-voters want to articulate political protest by abstaining from voting. They often have a strong party identification and see abstaining from voting as “abstractions” from their party. Non-voter researcher Michael Eilfort sees abstention from voting as the result of a conscious decision by politically informed and interested citizens . The non-election for reasons of political protest is sometimes also explained with the approach of the rational voter , for example if non-voters are of the opinion that with the help of their withdrawal of votes, a programmatic reorientation process can start in the “punished party” immediately after the election. “Rational” non-voters then value the expected personal benefit of such an intra-party debate higher than an otherwise customary vote for this party.

The so-called bogus non-voters , also known as technical non-voters , arise from incorrect electoral registers (e.g. people who died shortly before the election are still listed in the electoral registers), postal voting documents sent too late , illness or corresponding short-term prevention. This group is estimated at 4 to 5% of non-voters.

A study by the Bertelsmann Foundation published in September 2015 on the participation of different social milieus in the 2013 federal election shows that the participation of the social upper class is up to 40 percentage points higher than that of the socially weaker milieus. This means that the socially disadvantaged milieus are underrepresented by up to a third in the election results. Their share of non-voters is almost twice as high as their share of all eligible voters. At the same time, the socially stronger milieus are clearly overrepresented. This social split in voter turnout, the study continues, is systematically underestimated in polls on elections.

A study by DIW ( German Institute for Economic Research ) with a view to the period from 1990 to 2014 shows that voter turnout in federal, state and local elections in the new federal states is almost consistently noticeably lower than in the old federal states. In the federal elections, according to the work published in September 2015, it was always between three and eight percentage points lower in the east (excluding the state of Berlin) than in the west. The historically low voter turnout in state elections is clear. In 2014, for example, in Saxony and Brandenburg only less than 50 percent of those eligible to vote cast their votes.

Interpretation of the phenomenon

Need to explain and evaluate failure to vote

The phenomenon of not voting is assessed differently. Two opposing theses face each other. While representatives of the crisis thesis mainly want to identify disenchantment with politics , protest and a rejection of the system behind the abstention from voting , others see a longer-term normalization behind the increasing number of non-voters compared to other western democracies.

Normalization thesis

It says that the system works and that citizens are so satisfied with it that voters no longer feel they are needed in every election. In addition, the politically uninterested in Germany would now refuse to vote, as has always been the case in other democratic countries. With the decline in voter turnout, the Federal Republic is simply being gripped by a trend that began earlier in other western democracies - this way of thinking does not speak of a symptom of crisis. Social change, dealignment and increasing flexibility in voting behavior make non-voting another accepted option for swing voters.

Crisis thesis

Proponents of this thesis, on the other hand, see the decline in voter turnout as a signal of diverse political dissatisfaction and an increasing anti-party stance. According to this thesis, the development in Germany is based on the increased refusal of votes by politically interested citizens and is to be understood as a warning signal. In this way, non-voting is a consciously used means of expressing dissatisfaction and protest - the much-invoked "memo" and thus an act of political behavior.

For example, the study of non-voters in Germany found that the thesis that non-voters “rather did not vote because of a feeling of satisfaction with the political and social conditions” has been clearly refuted. On the contrary, it shows that “dissatisfaction with the way in which many political actors conduct politics today” is the main motive of non-voters to no longer take part in elections. The study Precarious Elections - Hamburg also comes to the conclusion that the lower the voter turnout, the more unequal it is. A falling voter turnout often conceals increasing social inequality in voter turnout. "The socially stronger groups of society continue to participate at a comparatively high level, while the participation rates in the socially weaker milieus collapse massively." Voter participation is becoming more socially selective and the election results are less and less socially representative in the sense that in them the views and Interests of all population groups would be expressed according to their share of the electoral population .

If, however, in a representative democracy, the will of large sections of the population is no longer articulated and no longer included in the process of political decision-making due to a lack of representatives who were elected by them, then the legitimacy of the entire political system suffers.

Need of explanation of choosing

The psychologist Thomas Grüter puts forward the thesis that in the context of the "economic theory of democracy" in the tradition of Anthony Downs (" An Economic Theory of Democracy ") it is irrational behavior for individuals to take part in elections. “From an economic point of view, there is no point in voting. You have to [...] take the time to study the election programs and go to the polling station. In return you get a tiny share of participation in the composition of parliament. The yield is therefore close to zero and - viewed rationally - does not justify any expenditure. "

It must be explained why, in view of this, citizens still take part in elections. Whether considerations of the homo oeconomicus are compensated by the fact that "the voters [...] view participation in the election as a civic duty [...] or as a social ritual whose meaning is not questioned" has not yet been researched. In theory, too, according to Grüter, there is “no model that could satisfactorily explain why people prefer a party or even vote.”

literature

- Tomas Marttila with Philipp Rhein: Why people don't vote - An empirical study on the political worlds in Munich , study (PDF; 1.25 MB) by the Institute for Sociology at the LMU Munich, November 23, 2017.

- Klaus Poier: Non-voters. A study on aspects of democracy, the extent and causes of not voting and possible counter-strategies . NWV - Neuer Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-7083-0278-8 (series of publications for public law and political science, 2).

- Norbert Kersting: Non-voters. Diagnosis and attempts at therapy . In: Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft , 14, 2004 ISSN 1430-6387 , pp. 403-427.

- Karl Asemann: Voters and non-voters in Frankfurt am Main through the ages . Election results against the background of current events and as reflected in the statistics . Citizens' Registration Office Statistics and Elections of the City of Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 2002 (materials for city observation, 10 ISSN 0945-4357 ).

- Thomas Renz: Non-voters between normalization and crisis. Interim assessment of the state of a never-ending discussion . In: ZParl , 28, 1997, pp. 572-591.

- Dag Oeing: Spain abstained from voting. The non-electorate in structural change? Profile and motives of the Spanish non-voters . Microfiche output. Tectum-Verlag, Marburg 1997, ISBN 3-89608-486-0 (Science Edition, Romance Studies series 12).

- Gisela Lermann (Ed.): Non-voters: Why I don't want to vote anymore. Voices on the current disenchantment with politics . Gisela Lermann Verlag, Mainz 1994. (With a contribution by Eckart Klaus Roloff ), ISBN 3-927223-61-1 .

- Michael Eilfort : The non-voters. Abstention from voting as a form of voting behavior . Ferdinand Schöningh Verlag, Paderborn u. a. 1994, ISBN 3-506-79324-1 (Studies on Politics, 24; also Univ. Tübingen, Diss., 1993).

Web links

- Manfred Güllner : Non-voters in Germany . (PDF) Friedrich Ebert Foundation , 2013

- Turnout and non-voters . Federal Agency for Civic Education , November 19, 2013

- Non-voters - Studies on the 2013 election . Federal Agency for Civic Education , September 16, 2013

- Study on the situation 2014/2015 (PDF) State Center for Political Education Saxony-Anhalt; accessed on October 7, 2015

- Non-voters in Germany. direct-demokratie.de; accessed on March 4, 2014

- Turnout: non-voters and protest voters . Federal Agency for Civic Education , May 20, 2009.

- Reinhard Jellen : We are not yet giving up on the ailing patient . telepolis , January 24, 2008

Individual evidence

- ^ Federal Returning Officer - Earlier European elections ( Memento from October 9, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Federal Returning Officer - Bundestag election: 2017 and earlier .

- ↑ Baden-Württemberg State Statistical Office .

- ^ Bavarian State Office for Statistics and Data Processing .

- ↑ wahlen-berlin.de and election.de .

- ↑ Statistics election results in Brandenburg .

- ↑ State Statistical Office Bremen ( Memento from February 15, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 27 kB).

- ↑ Preliminary 2015: tagesschau.de .

- ↑ achwir's homepage - elections ( memento of the original from July 6, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. and Statistics North .

- ^ State elections in Hesse 1946–2013 , Hessian State Statistical Office.

- ↑ Preliminary results 2018 .

- ↑ State Returning Officer Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania .

- ↑ State Office for Statistics and Communication Technology Lower Saxony and 2017 result.

- ^ Regional Returning Officer North Rhine-Westphalia .

- ↑ Regional Returning Officer Rhineland-Palatinate ( Memento of the original from August 26, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Regional Returning Officer - Statistical Office .

- ↑ State Statistical Office of the Free State of Saxony .

- ↑ State Returning Officer for the State Statistical Office of Saxony-Anhalt ( Memento of the original from April 2, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Statistical Office for Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein May 7, 2012 and landtagswahl-sh.de 2017 ( Memento of the original from May 7, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Thuringian State Office for Statistics .

- ↑ Luc Bronner: L'abstention en banlieue, plus grave que les émeutes? Le Monde , March 25, 2010 (French).

- ^ Analysis of the Bavarian state elections in 2003, voter migration , LMU.

- ^ Analysis of voter migration , tagesschau.de .

- ↑ Eva Marie Kogel, Romy Schwaiger: Why do so many Germans not want to vote? In: Die Welt , August 21, 2013.

- ↑ Bundestag elections “Non-voters and protest voters”. Federal Agency for Civic Education , 2002.

- ^ "Non-voters: The third strongest force" , stern.de , October 11, 2005.

- ↑ Tom Strohschneider: Democrats on the sofa. Now the non-voter is being beaten again. But who is that actually? In: Neues Deutschland , 6./7. September 2014, p. 20.

- ↑ Political inequality - new estimates show the social divide in voter turnout . In: Einwurf , 2/2015, Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- ↑ 25 years of German unity: Political orientations in East and West Germany are still different . German Institute for Economic Research , press release, September 9, 2015.

- ^ Manfred Güllner: Non-voters in Germany . (PDF) Study on behalf of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation , 2013, p. 85; accessed on February 24, 2015.

- ↑ Dräger, Vehrkamp: Precarious elections - Hamburg . (PDF) 2015, p. 7; accessed on February 24, 2015.

- ↑ Thomas Grüter: Why voting is not profitable - and why democracy works anyway . BLOG: Thought Workshop - the psychology of irrational thinking. Spectrum of Science , September 12, 2013.