Antonio Foscarini

Antonio Foscarini (* 1570 in Venice ; † April 22, 1622 ibid) belonged to the Venetian nobility and was ambassador to Paris and London . He was the third son of Nicolò di Alvise of the family branch of San Polo and Maria Barbarigo di Antonio. In 1622 he was sentenced to death by the Council of Ten for high treason and executed.

Ten months later, however, he was rehabilitated by the same council , of which the European courts were expressly informed. Venetian historiography celebrated this revision of its own death sentence as an expression of the victory of the sense of justice over the raison d'être . The background, however, seems to be formed by factional struggles, which were extremely explosive before the conflict between church and state, as well as between Protestantism and Catholicism at the beginning of the Thirty Years War . The fact that an art-loving Spanish noblewoman played a role that was difficult to interpret in Venice made the event even more significant for the Venice myth .

Origin and early political career

Antonio Foscarini was the third son of Nicolò di Alvise of the family branch of San Polo and Maria Barbarigo di Antonio. The couple married in 1556. They had three sons, Antonio was the youngest, and three daughters. The eldest son was Alvise (1560-1617), he married Lucrezia Gradenigo. The middle son, Girolamo (1561–1580), died early. The daughters were Caterina, who married Lorenzo Priuli in 1583; Agnesina, who successively married Marco Priuli, Leonardo Molin and Luca Contarini; finally Lucia, who went to the monastery. During the war over Cyprus (1570–71), the Foscarini lost considerable parts of their property, so that the parents could only provide material security for their sons. Antonio Foscarini's father Nicolò died in 1575, his brother Girolamo in 1580, and his mother died in 1582, probably by her own hand.

Antonio went to Padua , a time that gave birth to a number of friendships that accompanied his life. From 1590 he ran the house with his remaining brother Alvise, but in 1592 the two shared the still considerable fortune of around 70,000 ducats by mutual agreement . This fortune included estates in Padovano, Mestrino, Veronese and some properties in Venice, including the family home in San Polo. From 1595 he had a seat in the Grand Council. In September 1597 he was appointed Savio agli Ordini selected which he at the lowest level to the central body of the power College reached. There he gained insight into the struggles and lines of conflict between conservatives and innovators, two groups within the nobility that were increasingly facing each other. He himself became a supporter of the innovator Paolo Sarpi .

Diplomatic career

Foscarini began his political career as an envoy to the court of Henry IV of France in 1601. In this capacity he witnessed the marriage between the king and Maria de 'Medici . He was elected again on May 26, 1607 to the Ambasciatore ordinario in Francia , but did not take up this position as ambassador to France until February of the next year.

In July 1610 he was appointed Ambasciatore ordinario in Inghilterra , that is, ambassador to England , but he also took up this position late on May 4th of the following year.

Not only did these delays appear as allegations against him during his two trials, but it was also found that he was otherwise not behaving appropriately. He was often poorly dressed - a reproach that was of no small importance in the class society . He also made no secret of his opposition to the Pope and the Jesuit order . At the same time he was considered stingy.

First arrest

Foscarini's secretary, Giulio Muscorno, denounced him to the Council of Ten in February 1615 . He accused Foscarini of selling secrets to the political opponent Spain . Muscorno was allowed to return to Venice in March. From April to June he was replaced by Giovanni Rizzardo, who was given the secret assignment to collect evidence against Foscarini. Foscarini returned to Venice in December, where he was imprisoned on arrival. Only after three years was he released without being charged, and on July 30, 1618 even formally acquitted of all guilt. His successor as ambassador to England, Gregorio Barbarigo and his secretary Lionello, searched in vain for evidence in London between January 1616 and June 1617. In 1620 Foscarini even became a senator.

The Countess of Arundel and the Second Arrest

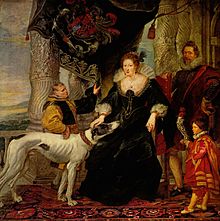

In 1621 Alatheia Talbot , Countess of Arundel , reached Venice. She was the granddaughter of Elizabeth of Hardwick , goddaughter of Queen Elizabeth I , and the wife of Thomas Howard , the twenty-first Earl of Arundel , a leading figure in the court of King James I of England. During her stay, Countess Arundel lived in the Palazzo Mocenigo on the Grand Canal . Foscarini knew the art-loving couple from London and visited them in Venice in the Mocenigo Palace.

On April 8, 1622, Foscarini was arrested while leaving the Senate. The Council of Ten accused him of having met with ministers from foreign powers, both in Venice and outside, and of having betrayed the most intimate secrets of the republic to them in words and in writing for money. This happened in the house inhabited by the Arundels, where Foscarini entrusted secrets to the secretary of Emperor Ferdinand II and the Pope's nuncio . The agents of the State Inquisition Domenico and Girolomo Vano were the main witnesses. These in turn had received their information from Gian Battista, the servant of the Spanish ambassador.

Sir Henry Wotton , England's ambassador to Venice, wrote to Arundel that the Senate would declare her an undesirable person . She should therefore leave the city immediately. Instead, she rushed to the ambassador and informed him that she wanted an audience with Doge Antonio Priuli . She threatened to have the ambassador, whom she suspected of being involved in the action of the Council of Ten, recalled. In fact, not only was she allowed to see the doge, but the doge said that no one would banish her. In addition, the Doge promised her that he would restore the honor of Foscarini by writing to London. Six months later she left Venice with gifts from the Doge.

On April 22nd, Foscarini was sentenced. He was strangled in prison and hung upside down between the pillars in the piazzetta , as is customary in high treason . He hung on one leg from morning to dusk, his face scratched because his body had been dragged across the floor.

rehabilitation

At the same time, one of the inquisitors, who mistrusted the Spanish servant, had another questioning and he confessed that he had never seen Foscarini in the house of the Spanish ambassador. Girolamo - he had received wages for services not mentioned on May 23rd - and Domenico Vano were summoned and questioned in August. The two confessed to having discredited Foscarini on false accusations, but the brief court records do not reveal why they did so or who might have caused them to do so.

Between the sentencing and the execution of the two Vano, the nephews Foscarinis, Nicolò and Girolamo Foscarini tried to get an interrogation to uncover who might be behind it, but the Council of Ten refused. The English ambassador pondered whether this was done because the statements of convicts were of no value or for reasons of state.

On January 16, 1623 Antonio Foscarini was acquitted of all guilt by the Council of Ten, after the same council had found him guilty of high treason ten months earlier and sentenced him to death.

The prosecutors at the time had to appear before the State Inquisition and the Council of Ten. The latter publicly acknowledged his error. Copies of the corresponding letters were sent to Foscarini's family and to all European courts. Venice thus underpinned its reputation for inexorable justice, even against its own people.

Foscarini was exhumed and given a state funeral . In the Church of San Stae on the Grand Canal, there is now a statue of the executed man in the Foscarini Chapel. The Doge Marco Foscarini (1762–1763), a descendant of Antonio's brother Alvise, expressly praised the Council of Ten for revoking their own judgment.

backgrounds

Antonio Foscarini was a supporter of the so-called Giovani , a group in the Venetian nobility with sympathy for the Protestant rulers who supported them during the Thirty Years War. When Foscarini was ambassador in London, he made friends with Sir Henry Wotton (who later became the English ambassador to Venice) and operated a formal alliance with England.

In addition, Venice had drawn conclusions in a legal dispute since 1605 and banished Theatines , Capuchins and Jesuits from its dominion. In return, the Pope had imposed the interdict on Venice on April 17, 1606 . Although this was lifted in 1607, the Jesuits were not allowed to return. The republic ostentatiously placed itself above the Pope in church matters. In addition, Venice mistrusted the Jesuit order, which was strongly tied to Spanish interests, and also viewed Spain, which was in league with Florence , Milan and Naples , as an overpowering factor that could unfavorably shift the unstable balance of power in Italy. Besides Venice, only Savoy was not subject to Spanish domination. The leader of the anti-papal group, which did not want to grant the Pope privileges in secular matters, was Paolo Sarpi .

The opponents of the Giovani , the young, were the Vecchi , the ancients, also called Papalisti , so called supporters of the Pope. Their conflict was an important backdrop to Foscarini's conviction. The boys dominated until the death of Doge Leonardo Donà (1606–1612) , but until 1631 they only had a temporary influence.

The Habsburgs, as leaders of the Counter-Reformation forces, for their part, embroiled Venice in a war led by Archduke Ferdinand , which resulted in the Peace of Madrid in 1617 . However, the Spanish viceroy in Naples , the Duke of Osuna , refused to lay down his arms. While his ships attacked Venetian traders in the Adriatic , rumors were circulating in Venice that the Spanish embassy formed a core of supporters against the city. Numerous Venetians threatened the embassy and the courts sentenced over a hundred men for treason. Three Spaniards were immediately executed.

Conversely, this attempted coup led to a strong anti-Spanish stance even among the pro-papal groups in Venice. It is telling that Giambattista Bragadino, a member of the impoverished nobility, the so-called Barnabotti , was also executed after he had to admit to having had contact with the Spanish ambassador. This and the crowds in front of the embassy caused the Spanish ambassador, the Marquis of Bedmar, to leave the city headlong.

It was in this atmosphere that Antonio Foscarini was denounced by his secretary Giulio Muscarno. Foscarini was arrested in 1615. Only after three years was he acquitted because he had apparently not sold any information to the Spaniards. Muscarno was stripped of his office and sentenced to two years in prison.

It cannot be decided whether it was Foscarini's previous indictment, his Protestant inclination, the personal hatred of his secretary Muscarno, or the deep-seated fear of the intrigues of Spain that led to the renewed denunciation in 1622.

The Council of Ten had been responsible for issues of high treason since 1310 . The composition of the Council of Ten is known for both important dates, the day of conviction (April 22, 1622) and that of rehabilitation (January 16, 1623). This council of ten, in which his six councilors sat next to the doge, consisted essentially of ten senators, even if a total of 17 men took part in its meetings. These appointed three trustees of the state or Avogadori di Commun , one of which had to be a council of the Doge, the other two were elected by the senators. The three Avogadori had numerous informers, informers and henchmen , their own cash register and they did not have to keep records. The ten senators in the council were only elected for one year by the Senate, but their terms of office were not identical, so that there was never a completely newly elected council of ten. On the contrary, its composition changed only every month.

In 1622 the Council of Ten was chaired by the Doge Antonio Priuli , who may have been a papalista . In any case, part of the family fortune was based on church sources of income. His two sons were priests, his seven daughters lived in monasteries , and his brother and uncle were bishops. Another papalista could have been Alvise Contarini , as well as Francesco Molin and Battista Nani . It cannot be established whether there were any other papalisti on the Council of Ten.

In 1623 the chairmen ( Capi ) were completely different, namely Anzolo da Mosto, Marcantonio Mocenigo and Nicolò Contarini . Contarini was, after Sarpi, one of the leading figures of the Giovani , Mocenigo supported him. Only Battista Nani, who was the third to sign the rehabilitation, was not one of them. On the contrary, Nani had been on the Council of Ten at the 1622 conviction, but he was one of the four who voted for imprisonment rather than execution.

Vincenzo Dandolo, who, like Nani, was present at both sessions, had meanwhile voted for the strongest condemnation. In 1623, however, he also voted for rehabilitation. He had known Contarini for a long time and probably owed him his seat in the Senate. They also fought together in the Gradisca War from 1615 to 1617.

However, it is not clear whether the fight between Giovani and Papalisti was the reason why Foscarini was executed and rehabilitated. In any case, Foscarini was so discredited in 1622 that Paolo Sarpi publicly rejected the 100 ducats from Foscarini's inheritance, which he had provided for Sarpi's prayers in his will on the evening before his execution. It is unclear whether Sarpi now found him guilty and therefore rejected the inheritance, or whether he saw himself and his group in danger.

Venice's semi-official historiography interpreted events in its own way. The revocation of one's own judgment was interpreted as a special sign of the Venetian sense of justice, which itself triumphs over the raison d'etre. The opponents of the Venetian constitution, however, interpreted these events - especially from the 18th century - as typical of the oppressive, secretive, decadent state, but especially of the cruel and treacherous Council of Ten.

It was probably not so much the Council of Ten that brought about the restoration of Antonio Foscarini's reputation for reasons of justice, but rather the idiosyncratic approach of the Venetian constitution that institutionalized the constant exchange of members in the Council of Ten. This enabled the Giovani to carry out rehabilitation at the moment of a favorable composition.

literature

- Jonathan Walker: Antonio Foscarini in the City of Crossed Destinies , in: Rethinking History , Volume 5, Issue 2, 2001, pp. 305–334.

- Murray Brown: The Myth of Antonio Foscarini's Exoneration , in: Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Reforme. Société Canadienne d'Études de la Renaissance 25/3 (2001) 25-42.

- Ida von Reinsberg-Düringsfeld : Antonio Foscarini , 4 vols., Stuttgart 1850.

See also

Remarks

- ↑ Further details from Jonathan Walker: Antonio Foscarini in the City of Crossed Destinies . In: Rethinking History . Volume 5, 2001, pp. 305-334.

- ↑ Samuele Romanin : Storia Documentata di Venezia , 10 volumes, Venice: P. Naratovich 1858, Bd. 7, p. 196. He dates this event to the year 1622 because it dates more veneto , that is, according to the Venetian calendar. In Venice, the new year didn't start until March 1st.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Foscarini, Antonio |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Venetian nobleman and ambassador |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1570 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Venice |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 22, 1622 |

| Place of death | Venice |