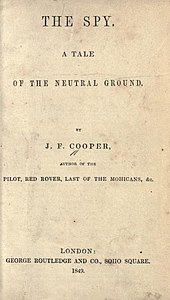

The Spy: a Tale of the Neutral Ground

The Spy: a Tale of the Neutral Ground is the title of the second novel by the American writer James Fenimore Cooper . The work, published by Wiley & Halsted in 1821 , is considered the first novel in American literature to be set in the United States and to achieve international recognition at the same time.

content

During the American Revolutionary War , Mr. Wharton withdrew from New York to his estate in Westchester County with his two daughters Sarah and Frances, the sister of his late wife, Jeanette Peyton, and his black servant Caesar Thompson . The Locusts estate is located in no man's land (English Neutral Ground ) between the front lines of the British Army in the south and the Continental Army commanded by George Washington in the north.

During a night storm, a plainclothes stranger who calls himself "Mr. Harper ”, admission to the Whartons. During a conversation between Harper and Mr. Wharton, his son Henry, who is serving in the British Army, appears, who has made his way through the American lines in disguise for his family, but is recognized by Harper as a British officer. In addition, the peddler Harvey Birch appears, who lives not far from the Whartons with his old father and his housekeeper and who is widely believed to be a British spy.

When the weather improves, Harper travels on. Before leaving, however, he offered Henry his help in gratitude for the Whartons' hospitality should Henry ever be in danger. A short time later, a Continental Army cavalry unit under the command of Captain Lawton arrived at the Whartons' estate. Lawton sees through Henry's disguise and arrests him as a supposed British spy. Fearing a possible conviction and execution, Henry's sister, Frances Lawton, asks Major Peyton Dunwoodie - a childhood friend of Henry's - for the release of her brother. However, when Dunwoodie finds a permit issued by General George Washington with Henry, he feels bound by his duty and defies Frances' urging.

When British troops reach The Locusts , Henry takes advantage of the general confusion and flees. He warns his superior Colonel Wellmere about the Americans led by Major Dunwoodie, who ignores all warnings and forces a fight. With the brave efforts of Captain Lawton, the Americans win the battle and capture both Henry and Colonel Wellmere, who was injured in battle. When Lawton also tries to capture Harvey Birch, who had watched the battle from a hill, he falls from his horse, but is spared by Birch.

One of the following nights, Birch is captured by a gang of outlaws in his father's house, the property is set on fire, and Birch is handed over to Captain Lawton as a British spy. Birch swallows a letter exonerating himself so as not to reveal the identity of his secret client. He is put in prison, but is able to escape wearing women's clothes that same night. The next morning, Birch warns Major Dunwoodie of the United States of any dangers the Whartons may face.

In the meantime, Mr. Wharton's older daughter Sarah, who is sympathetic to the British, has given her consent to the wounded British Colonel Wellmere to marry. During the hastily arranged ceremony, however, Harvey Birch appears and informs those present that Wellmere is actually already married in his English homeland. Sarah then goes into shock and Wellmere flees after a duel with Captain Lawton, through which Lawton tries to restore Sarah's honor. Shortly afterwards, The Locusts , the Whartons 'estate, is burned to the ground by the gang of outlaws who had also infected the Birchs' house. Captain Lawton saves Frances from the flames and Harvey Birch saves her sister Sarah. In gratitude for his own sparing in the past battle and the rescue of Sarah, Lawton lets the alleged spy Birch run instead of arresting him.

Days later, the Wharton family reached a Continental Army camp with some belongings, where Henry Wharton was awaiting trial and possible execution. In the course of his hearing, Henry pointed out that he snuck through enemy lines out of love for his family and not out of base motives. Due to his acquaintance with Harvey Birch, however, Henry is sentenced to death by hanging and the execution is scheduled for the next day.

The following night Henry manages to escape with the help of Birch. Frances suspects her brother and Birch to be in a nearby mountain hut, but to her surprise initially only finds Mr. Harper there. After describing all the events to Harper, Harper assures her that nothing will happen to Henry and sends her back to the American troops' camp. A little later Major Dunwoodie received a letter from General Washington in which the latter ordered Dunwoodie to refrain from pursuing Henry. With the help of Birch, he reached the city of New York and thus freedom. Frances and Major Dunwoodie marry, but their joy is overshadowed by the death of Captain Lawton in a battle with the British.

In September 1781, a meeting between Birch and General Washington took place at the headquarters of the Continental Army, during which it became clear that the mysterious "Mr. Harper ”was the commander in chief of the American troops himself. Washington offers Birch money for his services, but Birch refuses, on the grounds of his conscientiousness and patriotism. Fully aware that he would be branded as a British spy and traitor to the American cause for the rest of his life, Birch Washington promises secrecy until his death.

Thirty-two years later, during the British-American War , Captain Wharton Dunwoodie, son of Major Peyton Dunwoodie and Frances, meets an old peddler who informs him of British troop movements. When the peddler dies during a battle against the British, Captain Dunwoodie finds a letter from General Washington in his clothes, in which the latter thanks Harvey Birch for his loyal service and praises him as a loyal and courageous patriot.

Background: an American novel

While James Fenimore Cooper was finishing his first novel Precaution in 1820, he began working on The Spy . While Precaution follows the pattern of English social novels and imitates Jane Austen's late work Persuasion , Cooper set the plot of The Spy in Westchester County , where he had lived with his family since 1817 and which had been the site of numerous military conflicts during the American Revolutionary War. Up to this point in time, the common idea was that the audience could only be won over by romantic characters and locations, as offered by the English novels with their noble heroes living in castles and country estates. The English cleric and writer Sydney Smith summed up this notion in Edinburgh Review when he asked his readers “Who in the world reads an American book?” Alan Taylor points out in his introduction to the 2019 in the Library of America 's new edition of The Spy pointed out that English novels were more popular with American audiences at the time because the still young American society was still unsure of its own tastes and was culturally trapped in its self-image as colonists. Cooper himself remarked dryly that a murder committed in a castle is more interesting than one that is committed in a corn field.

For an American author there are several reasons to set the plot of a novel in his home country and even more reasons against it, wrote Cooper in the preface to the first edition of The Spy . It would suggest that the reader is confronted with a new and unused scenery. In this way, Cooper continues, the chance that the novel will gain attention in Europe increases. In addition, the national feeling of the American public secures sales opportunities in its home market. And last but not least, it is easier for an author to describe places and people whom he knows from first-hand experience and not just as a traveler. Cooper's biographer James Grossman sees this attempt at justification as the author's fear that his work might fail the audience. Indeed, before the work was published in December 1821, Cooper knew that the task of attracting an American audience to American etiquette and settings would be "arduous," according to a letter to his publisher.

When the novel was finally published by Wiley & Halsted at the end of 1821, Cooper's fears turned out to be unfounded. The Spy was immediately enthusiastically received by the audience . The American critics, on the other hand, discussed the work either with mild sympathy or with caution. Grossman attributes this to the uncertainties about the motherland. As a now independent nation, they wanted to escape the influence of British culture, but at the same time also wanted to impress the established literary critics in Great Britain. Before being judged by British reviewers, according to Grossman, in America there was no way of knowing whether the native author had produced a good work. The reluctance of the American reviewers turned out to be unfounded: despite some criticism of the portrayal of the character Colonel Wellmeres, the British reviewers gave The Spy a positive review and translations of the novel in French, German, Spanish, Italian, Russian, Swedish, and Danish appeared as a result and Dutch. This made Cooper's The Spy the first novel in American literature to be set in the United States and to gain international recognition at the same time.

literature

- Text output

- James Fenimore Cooper: two novels of the American Revolution - The Spy; Lionel Lincoln , ed. by Alan Taylor, New York 2019 (also Library of America, vol. 312)

- The Spy , Dt. by Helga Schulz, 2 vols., Berlin [u. a.] 1989, ISBN 3-351-01506-2

- Secondary literature

- Alan Taylor: Introduction , in: James Fenimore Cooper: two novels of the American Revolution - The Spy; Lionel Lincoln , New York 2019, pp. Xiii – xxi

- Section “James Fenimore Cooper”, in: Brett F. Woods: Neutral Ground: A Political History of Espionage Fiction , New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-87586-534-8 , pp. 16-22

- Lance Schachterle: Cooper's Revisions for His First Major Novel, The Spy (1821–31) , in: Hugh C. MacDougall (Ed.), James Fenimore Cooper: His Country and His Art, Papers from the 1999 Cooper Seminar (No. 12 ), Oneonta, New York 1999, pp. 88-107

- Dave McTiernan: The Novel as “Neutral Ground”: Genre and Ideology in Cooper's The Spy , in: Studies in American Fiction 25, 1 (1997), pp. 3-20

- Bruce Rosenberg: The Neutral Ground: The André Affair and the Background of Cooper's “The Spy” , Westport 1994

- T. Hugh Crawford: Cooper's Spy and the Theater of Honor , in: American Literature 63, 3 (1991), pp. 405-419

- John McBride: Cooper's The Spy on the French Stage , in: University of Tennessee Studies in Humanities 1 (1956), pp. 35-42

- Chapter "An American Scott: Imitation as Exploration and Criticism", in: George Dekker: James Fenimore Cooper: The Novelist , London 1967, pp. 20-42

- James Grossman: James Fenimore Cooper. A Biographical and Critical Study , Stanford, CA 1949, pp. 21-29

Remarks

- ↑ Dave McTiernan: The Novel as “Neutral Ground”: Genre and Ideology in Cooper's The Spy , in: Studies in American Fiction 25, 1 (1997), pp. 3–20, here p. 4.

- ↑ James Grossman: James Fenimore Cooper. A Biographical and Critical Study , Stanford, CA 1949, p. 17. McTiernan, The Novel as “Neutral Ground” , p. 4 also points out the similarity with the novels of the English writer Amelia Opie .

- ↑ See Alan Taylor, Introduction , in: James Fenimore Cooper: two novels of the American Revolution - The Spy; Lionel Lincoln , New York 2019, pp. Xiii – xxi, here p. Xv.

- ^ "In the four quarters of the globe, who reads an American book?", Sydney Smith: Rev. [iew] of Statistical Annals of the United States, by Adam Seybert , in: Edinburgh Review 33 (1820), p. 69 –80, here quoted from The Works of the Rev. Sydney Smith, including his contributions to the Edinburgh Review , 2 vols., London 1859, vol. 1, p. 292.

- ↑ “[…] English novels were cheaper and more fashionable for Americans, who still felt insecure about their own tastes and dismissive of native authors. Culturally they remained colonists. ", Taylor, Introduction , pp. Xvf.

- ↑ Steinbrink quotes Cooper with the words "[murder] is more interesting in a castle than in a cornfield" in: Jeffrey Steinbrink, Cooper's Romance of the Revolution: Lionel Lincoln and the Lessons of Failure , in: Early American Literature, Volume 2, P. 337, here cited from Taylor, Introduction , p. Xv.

- ↑ “There are several reasons why an American, who writes a novel, should choose his own country for the scene of the story - and there are more against it.”, Preface , in: James Fenimore Cooper: two novels of the American Revolution - The Spy; Lionel Lincoln , ed. by Alan Taylor, New York 2019, p. 3.

- ↑ "[...] the ground is untrodden, and will have all the charms of novelty.", Preface , p. 3.

- ^ "The very singularity of the circumstances, gives the book some small chance of being noticed abroad [...]", Preface , p. 3.

- ^ "Then, the patriotic ardor of the country, will insure a sale to the most humble attempts to give notoriety to any things national [...]", Preface , p. 3.

- ↑ "And lastly, an Author may be fairly supposed to be better able to delineate character, and to describe scenes, where he is familiar with both, than in countries where he has been nothing more than a traveler.", Preface , p. 3.

- ^ Grossman, James Fenimore Cooper , p. 24.

- ↑ "The task of making American Manners and American Scenes interesting to an American reader is an arduous one.", James Franklin Beard (Ed.), The Letters and Journals of James Fenimore Cooper , Cambridge 1960, Volume 1, p. 44, quoted here from McTiernan, The Novel as “Neutral Ground” , p. 5f.

- ^ Grossman, James Fenimore Cooper , p. 28.

- ↑ "[...] the self-contious clamor for a national literature arose as much from a desire to impress England as to escape her influence, so that until the English reviewrs had spoken one had no way of knowing how well a native writer had done his work. ”Grossman, James Fenimore Cooper , p. 28.

- ^ Grossman, James Fenimore Cooper , p. 29.