Tomba Regolini-Galassi

The Tomba Regolini-Galassi was found in 1836 in Cerveteri , the ancient Caere , and is located in the Sorbo necropolis southwest of the ancient city. The grave was untouched and was relatively well documented for the time. The burial contained a rich collection of gold objects that are now kept in the Museo Gregoriano Etrusco , part of the Vatican Museums . The grave is dated to the middle of the 7th century BC. And was named after Alessandro Regolini and Vicenzo Galassi, who found several tombs in the necropolis. Today the Tomba Regolini-Galassi is the only preserved and accessible tomb of the Sorbo necropolis, which, with its occupancy, dates from the Villanova culture of the 9th and 8th centuries BC. And of the 7th century BC The oldest cemetery in Caeres was the subsequent " orientalizing style ".

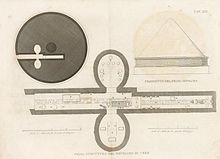

Grave complex

The tombs of the Tomba Regolini-Galassi were located under a tumulus 48 meters in diameter. The corridor-shaped grave complex was 37 meters long. About half of this was taken up by a 1.80 meter wide drom , which provided access to the actual burial chamber. This chamber was closed by a low wall, but had an opening in the upper area, which was probably used for the performance of grave rituals. At the end of the drom, just before the main chamber wall, an oval side chamber opened on both sides. The chamber on the right as seen from the entrance contained a large ash urn with the remains of an individual and some grave goods , while the left chamber contained grave goods, but no burial.

The lower part of the entire complex was carved into the existing tuff , the upper part was built up from ashlars and covered with a cantilever vault . When the grave was opened, the ceiling collapsed and destroyed some of the finds, most of which came from the actual burial chamber.

It was the grave of a woman whose skeleton was no longer preserved. She once lay on a kind of death bed, the floor was raised in the middle of the room. In the antechamber was a bronze bed with a skeleton. The right side niche contained an urn. The tumulus itself contained five subsequent burials in its peripheral area, which made its use up to the first half of the 5th century BC. Prove.

Grave goods

The find is mainly famous for the rich gold jewelry. A large gold brooch emerges from the grave, which is one of the most famous works of Etruscan goldsmithing. The fibula consists of a gold plate on which five lions are depicted. In the lower part there is a semicircular sheet of gold on which there are rows of griffins. Between these two gold plates are two elongated gold tubes decorated with a zigzag pattern. There is a needle on the back of the fibula. The function of the fibula is the subject of controversy, and the size of the fibula in particular is exceptional. Another unusual piece of jewelry from the grave is a large pectoral made of sheet gold, on which various animals are depicted. Two gold bracelets are granulated and show different rows of female figures.

Other objects come from the grave. These include golden plates that are decorated with Egyptian motifs. One of them is well preserved and shows two lions attacking a bull in the center. In the surrounding decorative band you can see a lion and an antelope hunt. The landscape is indicated by the depiction of palm trees, sycamores and papyrus. In the outer band there are four groups of chariots with soldiers. The plate has a hole in the middle and was probably once nailed to the wall of the burial chamber. Comparable plates were found in different places in the Mediterranean. They were probably produced in the Levant. There are various bronze vessels as well as the remains of a bed and a chariot. One of the bronze vessels is a cauldron that was found in the burial chamber. The basin is about 37.5 cm in diameter and decorated with six lion head protomes . The pool wall shows incised lions and cattle. The lion protomes look inward. Comparable protomes come from the realm of Urartu . This is where the vessel may have been made. Another cauldron, also decorated with lion head protomes, seems to be a local work. Here the lions look outwards. The inventory includes a situla made of silver , which shows various animals and plants in three registers in openwork. The vessel once had a wooden core.

The name of the buried woman was found six times on a set of silver vessels in the grave inventory : Larthia ; the extension Larthia Velthurus is also on a bowl - one of the earliest evidence of a gentile name , which in this case is derived from a personal name Velthur .

The interpretation of the grave finds is difficult because the old excavation report does not provide many details and the location of many objects within the grave is uncertain. A woman was buried in the inner burial chamber. While the urn burial in the side chamber probably belongs to a man. The gifts in the antechamber probably belonged to the woman and were used for funeral ceremonies before they were placed in the grave. Her body may first have been laid out on the bed that was found in the antechamber, before it was then transferred to the burial chamber on the chariot in a funeral procession. After the funeral ceremony, all objects used ended up in the grave complex. The bronze cauldrons in the antechamber are probably from a banquet. Such boilers are typical of the Eastern Mediterranean and their adoption is further evidence of the strong oriental influences that Italy was exposed to at that time.

literature

- Luigi Pareti: La tomba Regolini-Galassi del Museo gregoriano etrusco e la civiltà dell'Italia centrale nel sec. 7 AC Pontificia Accademia Romana di Archeologia, Vatican City 1947 ( online ).

- Corinna Riva: The Urbanization of Etruria, Funerary Practices and Social Change, 700-600 BC , Cambridge University Press, New York 2010, ISBN 9780521514477 .

- Maurizio Sannibale: The Etruscan Princess of the Regolini Galassi Tomb. In: Nikolaos Chr. Stampolidis (ed.): 'Princesses' of the Mediterranean in the Dawn of History. Exhibition catalog Athens 2012. Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens 2012, pp. 306–321 ( online ).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Luigi Pareti: La tomba Regolini-Galassi del Museo gregoriano etrusco e la civiltà dell'Italia centrale nel sec. 7 AC Pontificia Accademia Romana di Archeologia, Vatican City 1947.

- ↑ Mark Cartwright: Regolini-Galassi Tomb Regolini-Galassi Tomb. Ancient History Encyclopedia, February 23, 2017, accessed June 20, 2017.

- ^ Luigi Pareti: La tomba Regolini-Galassi del Museo gregoriano etrusco e la civiltà dell'Italia centrale nel sec. 7 AC Pontificia Accademia Romana di Archeologia, Vatican City 1947, plates 1–2.

- ^ Richard Daniel de Puma: Gold and Ivory. In: LN Thomson de Grummond, Lisa C. Pieraccini (eds.): Caere. University of Texas Press, Austin 2016, ISBN 978-1-4773-0843-1 , pp. 197-199.

- ^ Richard Daniel de Puma: Gold and Ivory. In: L N. Thomson de Grummond, Lisa C. Pieraccini (eds.): Caere. University of Texas Press, Austin 2016, ISBN 978-1-4773-0843-1 , pp. 196-197.

- ↑ Maurizio Sannibale: Bowl with Egyptianizing motifs. In: Joan Aruz, Sarah Graff, Yelena Rakic (Eds.): Assyria to Iberia: At the Dawn of the Classical Age. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York / New Haven 2014, ISBN 978-0-300-20808-5 , pp. 322–323, no. 193.

- ^ Riva: The Urbanization of Etruria , 152

- ↑ Riva: The Urbanization of Etruria , 142–146

Coordinates: 41 ° 59 ′ 33 " N , 12 ° 5 ′ 51.9" E