Aachen thermal springs

The over 30 thermal springs in Aachen are among the most productive thermal springs in Germany; they come to the surface in two headwaters in the Aachen city area. The thermal water flow in Aachen city center is 500 m long, a maximum of 50 m wide and is characterized by numerous spring headings, four of which are still accessible today, two of which are managed.

The thermal water flow from Burtscheid - a district of Aachen today - is 2200 meters long and is characterized by numerous upstream springs, which are concentrated in a lower and an upper group of springs. Eleven sources are still accessible there, four of which are still in use today. They are up about 72 ° C together with the thermal springs of Karlovy Vary to the heißesten sources in Central Europe .

The thermal springs have been used for healing purposes since the Roman settlement. They formed one of the essential factors for the political and economic development of Aachen, in particular the spa and bathing sector , the cloth and needle industry, and mineral water production .

Geographical location

The city of Aachen lies in a morphological basin . A large part of the catchment area of the thermal springs is geodetically in the area of the High Fens and the Aachen Forest, morphologically about 200 to 300 meters higher than the source points of the Aachen city center, so that the springs flow artesically . Only by constantly pumping out the main springs can the warm spring water be prevented from flowing off above ground and - as in earlier times - forming numerous warm ponds, ponds and swamps in the city.

Geology of the Aachen and Burtscheider thermal springs

The Aachen and Burtscheid thermal springs are bound to limestone stretches of the frasnium that emerge on the surface along large tectonic thrust orbits - the Aachen and Burtscheid thrusts. The thrusts occurred during the folding of the Variscan Mountains in the Upper Carboniferous .

While in Burtscheid the springs emerge in pure frasnium limestone, the springs in Aachen city center are concentrated on limestone banks in the marl slates of the frasnium, which are only a few meters thick . The approximately 50 square kilometers large catchment area of the thermal water extends mainly south of Aachen to the northern slope of the High Fens and takes up large parts of the Aachen forest in the west. A small proportion of the thermal water is also formed north of the Aachen thrust. The border of the northern catchment area is roughly the line Lousberg - Laurensberg . The rainwater that seeps away in these areas sinks to great depths of around 3000 to 4000 meters and is heated to around 130 ° C.

| parameter | unit | Rosenquelle (AC) |

Snake spring |

|---|---|---|---|

| sodium | mg / l | 1170 | 1100 |

| potassium | mg / l | 59.0 | 48.0 |

| ammonium | mg / l | 2.38 | 0.99 |

| Calcium | mg / l | 73.5 | 70.8 |

| magnesium | mg / l | 9.63 | 10.3 |

| Manganese , total | mg / l | 0.13 | <0.1 |

| Iron , total | mg / l | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| chloride | mg / l | 1020 | 1390 |

| fluoride | mg / l | 6.12 | 3.2 |

| nitrate | mg / l | <0.5 | <0.5 |

| nitrite | mg / l | <0.01 | 0.035 |

| sulfate | mg / l | 253 | 252 |

| Hydrogen phosphate | mg / l | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| Hydrogen carbonate | mg / l | 851 | 802 |

| Silica | mg / l | 56.0 | 47.3 |

| DOC | mg / l | 8.94 | 2.40 |

| Carbon dioxide | mg / l | 224 | 48.0 |

| Hydrogen sulfide | mg / l | 2.50 | <0.1 |

| Hydrogen sulfide (HS - ) | mg / l | 1.39 | <0.1 |

| arsenic | mg / l | 0.058 | 0.015 |

| Boric acid | mg / l | 5.44 | 4.88 |

| lithium | mg / l | 3.09 | 3.58 |

| oxygen | mg / l | 7.8 | 7.9 |

| Hydrocarbons | mg / l | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| Dry residue , 180 ° C | mg / l | 3550 | 3330 |

| hardness | ° dH | 12.46 | 12.26 |

In crevices and fissures of the limestone, it rises rapidly according to the steep strata in the area of the thrust orbit and flows out at the surface at up to 74 ° C in Burtscheid and around 50 ° C in Aachen. The karst crevices in the limestones widen into the 10–30 centimeter wide spring hoses typical of the region , the ascent tracks for the thermal water. During its underground passage, the former rainwater absorbs large amounts of dissolved salts and minerals from the rock formations stored in the underground. According to isotope studies, the age of the thermal waters in the Aachen area is assumed to be a few thousand to 10,000 years.

In the past, numerous earthquakes that recur in the area have partially affected the spring discharge and spring temperature - mostly for a short time. In numerous writings it is reported that smaller springs in the area of the lower Aachen spring group dried up after the great earthquake of February 18 and 19, 1756 and that the city officially had to defend itself in March 1756 against rumors about the complete drying up of the springs.

With a daily productivity of 3.5 million liters, the Aachen thermal springs are the most productive thermal springs in Germany, with the Burtscheider springs alone having a discharge of 2.2 million liters per day.

Physicochemical properties of the Aachen and Burtscheider thermal water

The Aachen and Burtscheider thermal springs are among the sulfur and fluoride containing sodium chloride hydrogen carbonate thermal baths . The Aacheners differ from the Burtscheider thermal waters both chemically and physically.

Due to the main direction of flow of the thermal water from the southwest, the hottest spring headings are in the southwest of the respective source line. The temperature decreases within the spring range to the northwest. The Burtscheider thermal springs are up to 74 ° C on average, around 20 ° C warmer than the springs in Aachen city center.

The characteristic smell that made Aachen thermal water famous is due to the increased sulfur content, especially hydrogen sulfide and other organic sulfur compounds. The Burtscheider thermal water - especially that of the upper spring group - is poorer in organic sulfur compounds and therefore more odorless due to its higher temperature . It is characterized by a high total mineralization of in part over 4500 milligrams per liter (Landesbadquelle / Schwertbadquelle).

The Aachen and Burtscheider thermal waters are said to have healing effects that are attributed to the high temperature and the ingredients. In addition to the high mineral content, the thermal waters contain numerous trace elements such as lithium , boron , fluorine and arsenic . From today's perspective, medically indicated use and consumption of small amounts is recommended.

The natural mineral water was the end of 2009 (for filling Aachener Kaiserbrunnen processed) so that the statutory provisions of the Mineral and Table Water Regulation corresponds, so the water was suitable for everyday consumption. The thermal water from Aachen and Burtscheid is one of the mineral waters with the highest fluoride content in Germany.

History of swimming pools in Aachen and Burtscheid

The earliest reliable references to the use of Aachen thermal springs can be found in the buildings of the Romans. Up to 6500 year old flint tools found near the sources, intensive Neolithic flint quarrying on the nearby Lousberg , Neolithic settlement remains in the city center and Bronze Age barrows in the Aachen forest allow conclusions to be drawn about a much earlier - if not continuous - settlement of the Region too. About a century before Christ, the area between the Rhine and Maas was the settlement area of the Eburones , a Celtic - Germanic tribe. A sanctuary of the Celtic god Grannus could have been located here at this time .

Roman consecration stones and coins as well as a statue from the first and second centuries AD, which were found in the area of a bathhouse in Burtscheid, suggest that a spa and medicinal bath also existed in Burtscheid in Roman times.

Development of the Aachen spa and bathing system

Roman time

The establishment of an important Roman vicus away from the major Roman traffic routes can be traced back to the existence of the hot springs in Aachen and Burtscheid. The Roman development in the vicinity of the thermal springs began after dendrochronological studies between 2 BC and 12 AD. The hot springs were exposed in the following period, the less productive ones were plugged with clay, stones and a kind of cement , so that the spring outlets were concentrated on only three productive springs - the Münster spring, the Quirinus spring and the Kaiser spring. In the middle of the 1st century, especially after the Batavian uprising in 69/70 AD, the construction of a spa began with the help of the Legio VI Pia Fidelis and the Legio XXX Ulpia Victrix with the construction of the thermal baths on the Büchel, which were fed by the Kaiserquelle.

A consecration stone from the second to third centuries found in 1974 during construction work in the area of the former thermal baths , donated by a Roman woman out of gratitude for her healing, is the oldest written testimony that reports on buildings in Aachen. The inscription on the stone, which could only be translated in recent years, reads:

"The deified emperors in honor of the (now ruling) imperial house (built) Iulia Tiberina, wife of Quintus Iulius (?) Avus, centurion of the 20th Legion Valeria Victrix , these temples of the Mater Deum and Isis at their own expense due to a vow, that they (herewith) gladly and because the goddesses deserve it. "

The Quirinus spring, probably the first thermal spring to be used by the Romans, fed a spring sanctuary at the end of the first century . The Bücheltherme, which was constantly expanded to a floor area of 2500 square meters, was in operation until at least the third quarter of the fourth century before the bathing pools were filled with rubble.

Probably in the last quarter of the first century AD, a second thermal bath was built in the area of today's Aachen Cathedral . The origin of the thermal water for the so-called Münstertherme has not yet been finally clarified. However, there are increasing indications that there was a supply of thermal water from the area of the Quirinus springs. Another theory assumes that there was a spring near the Anna or Hungarian chapel of the cathedral, but this has not yet been proven. The Münstertherme was probably also given up at the end of the fourth to the beginning of the fifth century. Building complexes, which are interpreted as accommodation houses and public buildings, complemented the thermal baths. Medical devices found in the immediate vicinity of the Elisengarten show the presence of an ophthalmologist in the immediate vicinity of the baths. During excavations that took place in the Elisengarten in 2008/2009, the remains of a Roman settlement were found that are connected to the nearby thermal baths.

To cool the hot thermal water, fresh water was fed into the city center from the area around Aachen via a system of water pipes made of baked clay or wood. Such lines have been dug up several times during construction work in the city center. The replica of a Roman portico with Corinthian capitals near where the original was found at the court is reminiscent of the old Roman bathing district in downtown Aachen.

Carolingian period to the late Middle Ages

After the Romans withdrew from the Rhineland in the first half of the fourth century, the thermal baths gradually fell into disrepair. An early Christian church was probably built in the area of the Münstertherme . The building material from the ruins of Roman Aachen was often used for other buildings in the city. In the following years the pagan temples, idols and votive stones were almost completely destroyed. For almost four centuries there is no reliable evidence of the use of the thermal springs. In 765 King Pippin the Younger spent Christmas and the following Easter in Aachen for the first time and bathed in the remains of the Roman thermal baths. In the period that followed, Pippin and his son Charlemagne visited Aachen several times at Christmas and Easter. Emperor Karl had the Palatine Chapel built over the ruins of the Münstertherme . At this point at the latest, the Münsterquelle was finally closed. The former bathing pools at the Büchel have been modernized. At the time of Charlemagne, according to reports from his biographer Einhard, the communal pools for over 100 people were one of the focal points of social and political life.

In 880/881 the Vikings destroyed a large part of the bathing facilities. Until the middle of the 13th century, the springs were in royal property and were leased. In addition to the rent, a campfire tax had to be paid for the use of the hot springs , as it was assumed that the hot water was heated by a fire inside the earth. The remains of the Carolingian thermal baths and the springs at the Büchel passed into the possession of the city of Aachen as fiefdoms in 1266 . The hearth tax was abolished by Richard of Cornwall as one of the few taxes in the empire. In 1295, in the immediate vicinity of the Quirinus spring, the Blasiusspital was built, which had a primitive bathing department and used the hot thermal water to heal the sick. The thermal baths were used by numerous pilgrims throughout the Middle Ages , and the baths were only closed during the plague epidemics (including 1349). From the 14th century, the hot water was also used in wool sinks, which were made near the Büchel. During the construction of the city wall at the end of the 12th century, several thermal spring precursors were discovered about 250 meters northeast of the Kaiserquelle, which were initially used as wool rinsing (compen) . In 1486 the first bathhouse was built in the new spring district with the Corneliusbad, which was followed by numerous others over the years.

The heyday of the Aachen bathing industry

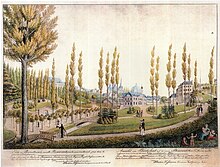

After the almost complete destruction of downtown Aachen by a devastating city fire in 1656, Franciscus Blondel's initiative began to plan one of the most modern bathing and health resorts of its time. A completely new spa center was built in the Komphausbadstrasse area with numerous public drinking fountains , gardens, spa hotels, hostels and new baths. The new bathing facilities included the Rosenbad, Corneliusbad and Karlsbad, which were later merged into the Herrenbad complex. The social focus was initially the Alte Redoute Aachen , which was replaced in 1786 by the Neue Redoute (today: Altes Kurhaus Aachen ) with a magnificent ballroom.

The French Revolution and subsequently the Napoleonic rule in the Rhineland led to a collapse in bathing life in Aachen and Burtscheid. The baths were used by the military for the medical rehabilitation of wounded and sick soldiers. After numerous stays with Empress Josephine and numerous family members of Napoléon , it was decided in 1811 to reconstruct and modernize the spa districts. For this, the bath houses and hot springs were on November 22, 1811 nationalized . A thermal palace was to be built in the area of today's city theater and the spa district was to be significantly enlarged. Financial bottlenecks and the end of French rule in Aachen prevented extensive expansion and new construction. Only the Kaiserquelle and the Rosenquelle were redesigned; the imperial bath was slightly rebuilt.

In 1818, the baths and springs nationalized by Napoléon were returned to the city of Aachen. In the period that followed, there was brisk construction activity in the spa districts on Büchel and Komphausbadstrasse, and numerous pools were given luxurious guest rooms with individual thermal baths.

In 1827 a new promenade was opened, with the rotunda of the Elisenbrunnen as the center, which was built according to designs by Johann Peter Cremer and Karl Friedrich Schinkel . In 1830, when the Theaterstrasse was built, a cold spring was discovered that carried mineral water containing iron . The spring was later expanded accordingly, sold as Leuchtenrathsches Heilwasser and a spa hotel was built. As the spring's replenishment rate was too low, the only hotel built on a cold mineral spring had to close again after twenty years.

In the 19th century, Aachen was a center for the treatment of the consequences of widespread syphilis . Due to the sulphurous thermal waters, which were used at the same time as the smear treatment containing mercury , this was better tolerated by the patients. Aachen's reputation as a syphilis bath led to a decline in wealthy spa guests, who increasingly preferred the fashionable baths in Wiesbaden , Bad Ems and Karlsbad .

In 1854 one of the city's most important sources of income, the casino, was closed at the behest of King Friedrich Wilhelm IV . In addition to the financial loss, the number of guests also fell by almost 50% within a year.

At the end of the 19th century, Aachen's importance as the center of European bathing culture continued to decline. Reasons for this were, in addition to the strong competition from other bathing resorts in Central Europe and the reputation as a syphilis bath, above all the increasing industrialization and the isolated spa and bathing districts in the city center.

At the beginning of the 20th century, attempts were made to revitalize the spa with a new urban planning concept. The Kurhaus on Komphausbadstrasse was extended and enlarged, and a change in the street layout created a connection to spacious, newly laid out parks.

In 1913 it was decided to build a new spa district on Monheimsallee . In addition to a new spa house , which also housed the Aachen casino after the Second World War , and a sophisticated hotel - the Quellenhof - a drinking and foyer and a spa center were built and an extensive park, part of today's Aachen City Garden , was laid out. The thermal water was led from the rose spring into the new spa district via a 600 meter long pipe. The First World War and the early 1920s - especially the Belgian occupation - were economically and politically difficult times for spa and bathing.

At the end of the 1920s, increased efforts were made to revive Aachen's tourist importance as a rheumatic bath. Renowned Aachen artists, including Jupp Wiertz , designed advertising posters for tourism.

The Second World War led to the complete cessation of the spa and bathing operations; individual bathhouses were initially used as military hospitals . Numerous air raids destroyed 90% of the spa and bathing facilities and spa hotels in downtown Aachen.

Spa and baths in Aachen after the Second World War

After the Second World War there were numerous plans to revive the spa business. A terraced park was to be created between the spa districts of Monheimsallee and Komphausbadstrasse, which would harmoniously connect the two spa districts.

The least destroyed bath in the city center, the Queen of Hungary bathhouse , was able to resume operation at the end of 1945, fed with thermal water from the Kaiserquelle. Due to the lack of fuel, the decision was made in 1948 to also supply the Elisabethhalle swimming pool not far from the Elisengarten with thermal water from the Kaiserquelle. From August 20, 1949, the first rheumatism cures could be carried out again on a small scale in the Badehotel Quellenhof. From May 1952, the spa business was resumed in the Corneliusbad on Komphausbadstrasse. The bathing facilities of the Rosenbad, Quirinusbad, Komphausbad and Neubbad, which were badly damaged or destroyed during the war, were not rebuilt. Numerous traditional locations for baths, spa hotels and drinking fountains gave way to modern uses such as department stores and parking garages.

The badly damaged Kaiserbad was demolished 15 years after the war, the spring system was renovated and replaced by a modern low-rise building.

In 1961 the Corneliusbad, the last spa in Komphausbadstrasse, was closed; In 1973 the Hungarian baths at Büchel were closed and the Roman baths were rebuilt (1973–1976) at the same location. Due to the decline in visitor numbers, the Kaiserbad was finally closed on February 23, 1984. With the closure of the Römerbad thermal baths on December 31, 1996 and the thermal swimming pool in the Quellenhof on December 30, 2000, an era of almost 2000 years of bathing tradition in Aachen city center came to an end.

On February 9, 2001, a spacious, modern thermal bath facility, the Carolus Thermen , was opened on the edge of the city garden, which continues the long Aachen bathing tradition from a modern point of view. The thermal water area of the leisure facility is supplied with water from the rose spring, which is brought in via an underground pipe.

History of the Burtscheid baths

The beginnings of the Burtscheid bathing industry

The thermal springs in Burtscheid - like the hot springs in the city center - have been used since the Romans occupied the Rhineland. In a wooded valley over 15 large hot springs rose over a distance of 300 m. The thermal springs of Burtscheid were already used in spa facilities by private individuals as early as the 1st and 2nd centuries. A nymphaeum was probably built in the vicinity of the springs out of gratitude for healing and recovery . In the area of today's sword bath, a woman's statue and an Apollo stone were discovered from the 1st and 2nd centuries , which could probably have served to decorate the spring sanctuary.

After the Romans left, these sanctuaries were also destroyed. The use of the hot springs was revived by monks from the Burtscheid Monastery , which was built here in 997. Reports of numerous bathing establishments run by monks have come down to us from the 11th and 12th centuries. In 1220, the Burtscheid Abbey was taken over by Cistercian women, some of whom also managed the thermal springs. In 1222, the Cistercian monk Caesarius von Heisterbach describes a bathing basin into which the thermal water of the Heißenstein springs (today: Landesbadquellen) was channeled and was mainly used by the poor. In the 14th century, numerous bathhouses were built in the Burtscheider Valley (1382 bathhouse Büdde , 1388 Schwertbad ), which often had their own thermal spring.

In addition to its use as a spa treatment, the thermal water from Burtscheid was used to bleach and rinse wool and cloth in wool rinses. Due to the high temperature of some thermal springs, the water could contain a. Scalded chickens and pigs or boiled eggs (cooking fountain) . The excess thermal water was discharged via the warm brook and supplied the surrounding ponds ( warm ponds ) with tempered water, so that continuous fish farming was possible. At the same time, the permanently warm, open waters in Burtscheid were the reason for the malaria epidemics that recurred until the middle of the 19th century and became known in the region as Burtscheid fever .

While the bathing and spa facilities in Aachen were constantly modernized in the 17th and 18th centuries, the situation in Burtscheid was more rural. In 1688 Franciscus Blondel describes 13 bathhouses with communal pools in Burtscheid. The bathing pools of the poor were mostly in the open air.

Like the Aachen springs, the Burtscheider thermal springs were nationalized by Napoléon Bonaparte in 1811. In 1818 all springs and bathhouses were sold to private individuals, only the Johannisbad found no buyer and was transferred to the poor institution.

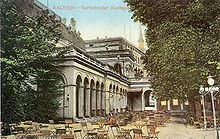

The heyday of the Burtscheid spa system

In the period that followed, the baths were modernized, a spa promenade and a spa park laid out (1858), drinking fountains (1854) and a glamorous spa house (1889) built. At the end of the 19th century, Burtscheid had eleven modern bathing hotels, most of them with their own thermal springs. In the Frankenberg quarter , in the area of the lower spring group, the Luisen- und Schlossbad were built in 1882 , which used the thermal water of the Mephisto spring. At the same time, Burtscheid developed into a center for the cloth and needle industry. At the end of the 19th century, the spa industry was in strong competition with advancing industrialization . Since 1840 the Burtscheid railway viaduct has separated the spa district in Burtscheid from the up-and-coming Frankenberg district.

Since the beginning of the 19th century, Burtscheid has also been a health resort for patients who were dependent on the help of charitable associations. From 1835 onwards, the association for the support of unprofitable foreigners who needed a well or bath at the mineral springs in Aachen and Burtscheid took on the care of the patients and from the middle of the 19th century enabled a spa stay in the association's own Krebs and Michaelsbad. From 1907 to 1912, a health clinic of the State Insurance Institution of the Rhine Province (Landesbad) was built near the Burtscheider market . In order to ensure that the up to 360 patients are supplied with thermal water, all thermal water advances in a vault in the area of the state spa have been rebuilt. The so-called state bath springs have supplied the health clinic of the state insurance company, the sword bath , the gold mill and prince bath, as well as the new bath and the cancer bath with thermal water since the beginning of the 20th century . Almost all Burtscheider bathing hotels had their own thermal springs, some of which were sometimes sent as mineral water.

Development of the Burtscheid spa system after the Second World War

The Burtscheid baths were also badly damaged in the Second World War. Of the eight baths that still existed at the beginning of the war, all in the area of the spa garden were completely destroyed; the state, gold mill, prince and sword bath badly damaged. In December 1947, the spa in Burtscheid began with only one guest in the Schwertbad. In 1948 cures could be carried out again in the Prinzenbad and Goldmühlenbad. After extensive reconstruction work, the state spa resumed operation in 1949. In the period that followed, the Burtscheider health clinics were renovated several times and adapted to the therapeutic requirements. Large thermal baths were built. In the area of the former spa garden, another rehabilitation facility, the rose clinic, was created in 1963–1967, which uses the thermal water from the rose spring as a cure product. In 2000, the Goldmühlen- und Prinzenbad closed the spa due to economic difficulties. Today, diseases of the musculoskeletal system are primarily treated in Burtscheid and rehabilitation after operations or accidents are carried out.

Healing indications

In ancient times the thermal water was used unsystematically as panaceum , as a panacea. It was used for general strengthening and rehabilitation after wounds and injuries. At the same time, the thermal bath was primarily a social meeting place until the early Middle Ages .

In the Middle Ages, the bathers made the first medical, albeit little scientifically founded, application of spa treatments and minor surgical interventions such as bloodletting and cupping .

Since the Baroque era , people began to use thermal water based on symptoms. In Aachen, the spa doctor Franciscus Blondel wrote a comprehensive medical paper on the use of Aachen and Burtscheider thermal water in 1688. Blondel developed the thermal water shower therapy for the treatment of rheumatic complaints and improved the technical implementation of steam baths . According to Blondel, diseases of the musculoskeletal system, skin diseases and the consequences of strokes were to be cured with thermal water applications. However, he also described contraindications such as high blood pressure and acute jaundice . In the 17th and 18th centuries, the following diseases were mainly treated:

- Rheumatic diseases, osteoarthritis and gout

- Rehabilitation after strokes, paralysis

- Skin diseases

- Stomach , kidney , gallbladder , spleen and liver ailments

- Melancholy & nervous disorders

- Metal poisoning

- syphilis

- Sterility & Women's Ailments

- scurvy

- asthma

- Emaciation , dizziness and ringing in the ears

In addition to the steam and shower baths and the spa treatment, Aachen thermal water has also been used as a drinking treatment since the Middle Ages .

Important spa doctors and pharmacists, such as Johann Peter Joseph Monheim and Gerhard Reumont and his son Alexander Reumont , have been systematically investigating the healing properties of thermal springs since the beginning of the 19th century. At this time, too, the focus was on the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, gout, osteoarthritis and skin conditions such as psoriasis and eczema . In the 19th century, Aachen gained supraregional importance in the treatment of syphilis and heavy metal poisoning, since the heavy metals (mercury ointment was used to treat syphilis until 1910) could not accumulate in the body as much due to the simultaneous use of drinking cures.

The focus of today's therapeutic applications is in the area of inflammatory and degenerative diseases of the musculoskeletal system, wear diseases, gout and osteoporosis as well as rehabilitation after accidents and operations.

Use of Aachen thermal water then and now

In the past, most of the thermal water was used as a cure and remedy . In the middle of the 19th century, with the construction of numerous bathing houses and hotels, the demand had risen to such an extent that the demand could only be met to a limited extent.

In addition to being used as a drinking cure, the mineralized thermal water was used for spa cures , thermal water showers and steam baths. Today the thermal water is still used in three health clinics in Aachen for therapeutic purposes. In addition, the Rosenquelle in Aachen supplies the Carolus Thermen, built in 2001, with thermal water.

The shipping of Aachen thermal water in bottles and barrels has been known at least since the end of the 17th century. In order to achieve the desired therapeutic effect, the spa doctors and pharmacists recommended that the mineral water be reheated before use. The transport of barrels with mineral water from the Kaiserquelle to the Russian border is documented. In 1700, the city of Aachen imposed an export ban on mineral water, which was tightened in 1723 because unsanitary filling methods damaged the reputation of the thermal water. Around 1830, the shipping of Aachen mineral water was again restricted because it was feared that this could reduce the number of guests. In 1884 the Kaiserbrunnen Aktiengesellschaft was founded by a Hamburg shipowner who also had the mineral water from the Kaiserquelle poured on the liner vessels operated by Norddeutscher Lloyd and the Hamburg-American Packetfahrt-Actien Gesellschaft (HAPAG). On December 31, 2009, Kaiserbrunnen Aktiengesellschaft ceased operations as the last bottling facility for Aachen mineral water.

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were also several smaller companies that bottled mineral water from Aachen and Burtscheid. In addition to the mineral water from the Kaiser spring, the Burtscheid mineral water from the Mephisto spring was also bottled until the end of 2009 . In addition, thermal salt and spring sulfur, which was used to produce artificial mineral water , were sold in the past .

At public fountains on Burtscheider Markt, on Friedrich-Wilhelm-Platz ("Faulbrunnen") and in Elisengarten , thermal water from the Kaiserquelle was sometimes given to the population free of charge. The use of the Elisen and Victoria fountain and the foyer on Monheimsallee, however, was chargeable. Some spa hotels, such as B. the Rosenbad in Burtscheid, the in-house springs (Rethel and Fastrada spring) have filled and shipped for guests for " follow-up treatment ". Two public fountains - the Elisenbrunnen and the Thermalbrunnen Burtscheid - are still operated today as drinking fountains with thermal water, other fountains use the hot water to maintain operation during periods of frost.

A small proportion of Aachen thermal water is used today as an additive for cosmetics .

The sources of the Aachen thermal water train

Upper Aachen source group

The Upper Spring Group includes all thermal water advances in the Aachen city center, which are concentrated between the cathedral and the Büchel. The last thermal water bath in the city center was given up in 1996. Until the end of 2009, only the water from the Kaiserquelle was used to produce mineral water.

Fountains under the Aachen Cathedral

The exact location of the thermal spring pre-eruptions below the Aachen Cathedral is unknown today. They are suspected based on the archaeological finds in the area between the Anna Chapel and the Hungarian Chapel. During excavation work in the area of the octagon in the past, groundwater with a temperature of over 20 ° C was found in the area of the foundation. During the most recent excavations, a thermal spring that was already sealed in Roman times was found. It is not known whether the spring pre-excavations were used to supply the Münsterthermen. According to the evaluation of recent archaeological investigations, it is assumed that the Roman Büchelthermen were supplied with thermal water from the Quirinus spring. Corresponding water pipes with thermal sinter deposits underpin this thesis. After the Romans withdrew, the Münstertherme fell into disrepair with the fountains.

Quirinus sources

The Quirinus springs at the court, which are built over today, are in the immediate vicinity of the Kaiserquelle. From the past up to five spring pre-eruptions have been known since Roman times, which fed a large and probably several smaller pools. In Carolingian times, the Quirinus springs - together with the Kaiserquelle - were probably used for Charlemagne's bathing pool. In 1295, the first hospital with therapeutic bathing departments, the Blasiusspital, was built over the head of the spring, which was primarily set up to provide medical care for the numerous pilgrims . In addition, the thermal water from these springs was used to supply numerous steam and shower baths in the spa hotels at the court, such as the Quirinus bath, the small bath or the bath of the Queen of Hungary . The spring temperature of the thermal springs built over today was 45 to 50 ° C in the middle of the 19th century. With a mineral content of 4 g / l, the Quirinus springs were as highly mineralized as the Kaiser spring. In 1962, the 5.0 x 3.1 m spring chamber, which was laid out in Roman times, was filled with concrete in order to increase the performance of the neighboring Kaiserquelle.

Kaiserquelle

With a current discharge of approx. 12 m³ / h, the Kaiserquelle is one of the strongest springs in the Aachen city center and has demonstrably been used for the Büchelthermen since Roman times.

The thermal water of the Kaiserquelle is 52 ° C and has a mineral content of 4.3 g / l. The spring water was still used by Kaiserbrunnen AG for the production of mineral water until the end of 2009 .

In the past, the Kaiserquelle has supplied numerous bathing pools, bathing houses and hotels with thermal water. In addition to the Roman Bücheltherme, this spring probably also fed the bathhouse of Charlemagne with a 14 x 9 m basin. In the Middle Ages, the Königsbad was built over the Kaiserquelle. In addition, the source supplied the surrounding bathhouses Neubad, Badhaus zur Queen of Hungary and the Imperial Bath, which was later rebuilt several times and which had steam baths and magnificent individual baths as early as 1829. At the end of the 19th century, the water and the warm exhaust air from the Kaiserquelle were used to heat the corridors and bath cells of the Kaiserbad.

A small proportion of the thermal water from the Kaiserquelle is constantly fed via a pipe to the Elisenbrunnen and feeds the drinking fountain there.

Since 2012, the thermal water of the Kaiserquelle has been placed under the protection of the Medicines Act. In addition to some structural changes in the basement of the Kaiserquelle and the designation of three protection zones, this has the consequence that the actual spring chamber can no longer be entered.

Nikolausquelle

The version of the Nikolausquelle is on the Büchel and is no longer used today. From old records it is known that the Nikolausquelle was 50 to 52 ° C warm in the middle of the 19th century and was mineralized similar to the Kaiserquelle. In the past, the thermal water of the Nikolausquelle was used as a fountain on the Büchel, for thermal water showers in the Dreikönigsbad (from 1823/24 Neubad) and for a short time as a supply line for the Kaiserbad. By pumping the thermal water from the immediately adjacent Kaiserquelle, the temperature of the spring has decreased to 31 ° C. The mineral content of the now unused spring is 3.9 g / l.

Great monarch

The version of the source of the former Hotel Großer Monarch is located in the area of a parking lot at the Büchel and is no longer used today. In the past, the spring partially supplied the hotel's baths. The Great Monarch is severely affected by the promotion of the neighboring Rosen- und Kaiserquelle . At the beginning of the 20th century, the spring still carried heavily mineralized thermal water with 41 ° C, today it is only around 20 ° C to 26 ° C warm and the thermal water is heavily diluted with groundwater close to the surface.

Lower Aachen source group

The thermal water springs of the lower group of springs were discovered during the construction of the inner city wall in 1171–1178 and were initially used as a woolen sink, washing facility and poor bath. In 1486 the first privately operated bathhouse, the Corneliusbad, was built. After the city fire in 1656, the city decided to build an urban bathing district in the area of Komphausbadstrasse with a spa promenade. In 1680, the cloth-making industry lost the rights to use the thermal springs because they wanted to prevent the spa guests from being bothered by acrid smells. The Komphausbad or the so-called poor bath , which existed as a communal bath until 1912, was fed from the overflow of all thermal springs in the lower group of springs .

Rosenquelle in Aachen

The thermal water of the rose spring in Komphausbadstrasse has been proven to have been used in the rose bath since 1632. Rebuilt after the city fire of 1656, at the time of the French occupation of Aachen, on the orders of Napoléon, the numerous springs were collected in a large spring chamber. Numerous secondary sources were suppressed by Napoléon's civil engineer Bélu from 1808 to 1811. In the course of this extensive construction work, a total of 14 primary springs were discovered in the area of the Rosenbad. Since the beginning of the 19th century, the mineral content of 4.0 to 4.2 g / l and the temperature of the spring water of 45–48 ° C has hardly changed. In addition to the bathing facilities in the Rosenbad, the thermal water from the Rosenquelle also supplied a public drinking fountain in the immediate vicinity. Today the spring has a discharge of about 43 m³ / h. A large part of the thermal water from the Rosenquelle is fed into the Carolus Thermen via a pipe ; only a small proportion of the thermal water is used in cosmetics production.

Marienquelle

The Marienquelle - sometimes referred to as the drinking spring - is located in the immediate vicinity of the early spring of the rose spring and was used at times to supply the drinking fountain on the promenade. Mineral content and temperature are strongly influenced by the extraction of the neighboring rose spring. The temperature of the Marienquelle is given in historical records as 46 to 47 ° C. Today the spring is no longer used.

Cornelius Spring

The Cornelius spring consists of a large number of spring pre-eruptions, which had an average mineral content of 3.7 g / l and were 45-46 ° C warm. In 1486 the first bathhouse in the area of the lower group of springs was built above this thermal spring. In the 18th century, the spring precursors fed three bathing pools, which were named paradise , purgatory and hell according to their temperature .

In 1762 Casanova stayed as a guest in the Corneliusbad. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the thermal water from the Cornelius spring was pumped to the drinking fountain on the promenade when the fountain was in use. In the past, the Corneliusbad was rebuilt several times and combined with the Karlsbad as the Herrenbad. The building was destroyed in the Second World War and later demolished; the thermal spring is now overbuilt and unused.

Karlsquelle

Not far from the Rosen and Marienquelle is the Karlsquelle, which is now also overbuilt and unused. It has been supplying the bathing and thermal shower facilities of the Karls- and Herrenbad since the 17th century. In 1870 the Charles Spring had a temperature of 44.5 ° C. In addition, the hotels received thermal water from the Cornelius spring as a cure in order to meet the needs of the guests.

The sources of the Burtscheid thermal water train

The Upper Burtscheider Source Group

Similar to the thermal water springs in Aachen city center, the Burtscheider thermal springs are divided into an upper and lower spring group. The Upper Spring Group is concentrated in the center of Burtscheid and is characterized by hot, low-sulfur thermal springs. The thermal springs of the Lower Spring Group are located in the Frankenberg Quarter and are 25-30 ° C cooler.

Johannisbadquelle

The 62 ° C warm Johannis spring rises near the warm brook in Mühlenbend . In the 17th century the spring fed the women's bath, in which the nuns of the nearby Burtscheid Abbey bathed. After the decline of the abbey and the nationalization of the Burtscheider baths by Napoléon in 1811, the spring stream supplied the Johannis bath. In 1818, when all Burtscheider baths were to be given back into private hands, there was no buyer, so the Johannisbad was left to the poor institution. In 1832, a bathing hotel was built on the property, which had five bathing rooms and a steam bath and which obtained thermal water from the Johannis and Steinbad springs. In 1900 the hotel was demolished and the spring was built over.

Wollbrüh- or Steinbadquelle

The thermal spring, which has a temperature of over 70 ° C, is one of a series of early spring in the former Mühlenbend parcel . Today it is built over and is located directly in front of the rheumatism clinic. In the Middle Ages, the spring supplied the stone bath and was converted into a wool sink after the baths were closed. From the middle of the 19th century, the water from the spring was to be fed to the Victoria fountain in the Burtscheider Kurpark via iron pipes . However, this project had to be discontinued after a short period of operation due to corrosion of the pipes.

Landesbadquellen

Between 1907 and 1912, the state bath was built in place of a cloth factory in Mühlenbend. The worm was channeled in the area of the foundations. The Landesbad uses thermal water that is collected from eleven spring precursors of the Mühlenbend, including the so-called "hottest spring", in a collecting basin with a diameter of 13 m. Individual springs are among the hottest thermal springs in Central Europe at 74 ° C. The total mineralization of the thermal water of the state bath springs is 4.3 to 4.4 g / l. The thermal water reservoir has numerous Burtscheider baths, u. a. supplies the sword, gold mill, prince, cancer and new bath with spring water. Before therapeutic use, some of the thermal water had to be cooled to a tolerable temperature in cooling towers and open pools.

After being damaged by bombs, the building had to be renovated and reopened in 1949. The rheumatism clinic housed in the building had modern therapeutic facilities, especially for the rehabilitation of joint problems. In 2013 the clinic was sold to a group of investors who want to build modern apartments in parts of the building. Another part of the building is used by the SALVEA group, together with the neighboring Schwertbad. In August 2017, the management of the Schwertbad-Klinik and the Aachen-based energy supplier STAWAG announced that they wanted to use the thermal water of the Landesbadquelle to supply heat to the new buildings to be built by 2022.

Today the quarries of the Landesbadquelle have a total discharge of approx. 60 m³ / h. In addition to the on-site balneological use, the public drinking fountain ( market fountain ) is also supplied from the state bath springs.

Snake bath springs

The Schlangenbad, which was demolished in 1897, was partially located on the property of the Rheumatism Clinic and already had bathing cabins and steam baths in 1829, which were supplied with thermal water from the Schlangenbadquelle and two other springs that were fed from the Mühlenbend . At that time, the Schlangenbadquelle emerged directly below the dining room of the bathing hotel and was used as a drinking fountain on site until 1897. With 65–70 ° C and a total mineralization of 4.4 g / l, the Schlangenbad spring was one of the hottest and most mineral-rich springs in Burtscheid. Today the Schlangenbad spring is approx. 15-20 ° C cooler and is no longer used. It is located under a concrete cover directly in front of the entrance to the former rheumatism clinic.

Schwertbadquelle

The Schwertbad is probably the oldest bathhouse in Germany. Finds of Roman votive stones and statues on the property are evidence of a bathing culture that is almost 2000 years old. The bathing pools and shower facilities of the Schwertbad were fed by hot springs of over 70 ° C, which arise in the Mühlenbend corridor . The Schwertbad also has its own thermal spring at 67 ° C with a total mineralization of 4.3 g / l, which arises between the facade of the bath and the rheumatism clinic. The current spring discharge is around 1.2 m³ / h. After the building was partially destroyed in 1944, the Schwertbad was reopened for spa operations in 1947. The Schwertbad currently has a modern thermal swimming pool, which is mainly fed with thermal water from the state spa springs.

Großbadquelle

The 71 ° C large bath spring rises directly on the square in front of the Schwertbad and fed the large bath, which was located there until 1832, with thermal water. In 1851 the vault of the Großbadquelle collapsed. In the course of the redesign of the Burtscheider market, the building was demolished in 1890. The thermal water of the Großbadquelle supplied a public thermal water fountain on the Burtscheider market, the so-called crinoline . Since the beginning of the 1950s, the spring has been built over as part of road redevelopment work.

Cooking fountain

The Kochbrunnen is located on Dammstrasse in front of the Neubad and was also called the Heisse Born buysen dem Driesch or warm puddle in the past . At the beginning of the 19th century, the hot, gaseous spring was provided with a wooden frame, but it fell into disrepair rather quickly. In 1865 the spring basin of the Kochbrunnen was provided with an oval stone frame, which below the spring water level had an inlet to the neighboring Krebsbad and Neubad. The name Kochbrunnen goes back to the fact that in past centuries poultry and pigs were scalded in this fountain and eggs were boiled - mostly to entertain the spa guests.

As a result of the construction of the Burtscheid sewer system in 1903, the thermal water level in the well and the temperature fell from 72 ° C (1886) to approx. 44 ° C (2007). The source is unused today. As part of a thermal water route Aachen project , experiments at the Am Höfling primary school in 2008 showed that the temperature today is no longer sufficient to boil eggs.

Neubad and Drieschbad springs

In the course of the amalgamation of the old town hall with the outdated Drieschbad, three spring precursors were developed in 1883, but they could only cover part of the thermal water requirement for the new bath. The new bath springs were 61–63 ° C and their bedding was severely affected by the sewer system implemented in 1903 . The necessary thermal water was supplied from the nearby boiling well. After severe war damage, the new bath was partially demolished and the springs built over.

Cancer bath springs

The Krebsbad springs arise on the right side of the warm brook below the church of St. Michael . The cancer bath was first mentioned at the end of the 17th century in the description of the bath by Franciscus Blondel . In the first half of the 18th century, the bath and the bath vault were rebuilt by the city architect Laurenz Mefferdatis and were very popular with spa guests in the period that followed. Frederick the Great stayed in this bathhouse in 1742. In 1829 the Krebsbad had two steam rooms and eight shower rooms. In 1835 the Krebsbad was taken over by the association for the support of unprofitable foreigners who needed a well or bath at the mineral springs in Aachen and Burtscheid . In 1886 the Krebsbad was demolished because it was in disrepair and replaced by a new building in 1887. The less productive 62–78 ° C hot spring precursors of the Krebbad were also supplemented by thermal water that was supplied from the boiling well. In 1903 the Krebsbadquelle was artificially deepened. From 1904, thermal water from the Wollbrühquelle was also supplied to supply the pool . In 1928 the Krebsbadquellen poured only 3.8 m³ of thermal water a day. Today the sources are unused.

Michaelsquelle

The today 32 ° C warm, unused Michaelsquelle rises in the garden between the Dammstrasse and the church St. Michael . In the Middle Ages, the spring supplied numerous smaller bathhouses. At the beginning of the 19th century, after the baths were closed, it was only used as a wool brewing source and washing source. The Michaelsbad was rebuilt from 1880 to 1882 by the association for the support of unprofitable foreigners who needed a well or bath at the mineral springs in Aachen and Burtscheid and the spring water for the baths was raised by means of a gas-powered pump. The individual small springs that were combined to form the Michaelsquelle were between 56 and 64 ° C in 1886. The Michaelsquelle was one of the most productive springs in the Dammstrasse with a filling of 120 m³ on the day 1928.

Rosenquelle (Burtscheid)

With a spring discharge of around 14 m³ / h, the rose spring is one of the most productive springs in Burtscheid and is still used today for therapeutic purposes in the rose clinic. Today's rose spring brings together two large, 57 and 66 ° C warm and several smaller spring precursors. It had been supplying the Rosenbad for at least the 17th century, which in the 19th century was the largest bathing hotel in Burtscheid with several shower, gas and steam baths. Most of the rooms had their own bathroom cabinet since the middle of the 19th century. A special feature of the rose bath was a thermal water shower with a height of 13 m, which was used to treat joint problems. In order to meet the water requirements of the bathing hotel, the main spring was deepened in 1866 and thermal water from the nearby Krebsbad spring was temporarily used.

In addition to being used as a spa treatment, the water from the rose spring was poured in a drinking fountain and, from 1867, warmed the promenade floor. The less productive rose spring, which before the Second World War was known as the Fastrada spring z. Some of it was bottled and sold to hotel guests, was on a vacant lot between Michaelsbad and Rosenbad. The most abundant spring of the rose bath with a pouring of 200 m³ a day, which was occasionally marketed as the Rethel source, originated in the courtyard of the rose bath. The Rosenbad was completely destroyed by twelve bomb hits during World War II. In 1961 the rose spring was redrafted 25 m north of the Rethel spring.

A donation from AMW Projekt Norbert Hermann in the amount of 70,000 € made it possible in 2013 that the entrance area of the Rosenquelle can be redesigned and partially made accessible to the public.

Carlsbad springs

The Carlsbad springs were discovered during construction work in 1844. Seven spring pre-eruptions with 52–65 ° C warm thermal water are located on the property of the Karlsbad - also called "Schmetzbad", which was built between 1844 and 1848 on the edge of the Burtscheid spa park. The daily spring discharge of the Karlsbad springs was 120 m³ in 1928. The building, which had been rebuilt several times, was completely destroyed in the war and subsequently demolished. The sources are no longer accessible today.

Victoria Spring

The numerous unmounted spring precursors in the lower field flowed into trenches and pits outside of the residential buildings in the late Middle Ages. The so-called poor baths developed out of these warm pools under the open sky . In 1688 Blondel reported on catastrophic hygienic conditions, as cattle were to be found in the ponds alongside people. The rich Victoria spring was discovered in 1609 when a karst crevice was uncovered. In 1831 the Victoria fountain was built over the 54–60 ° C hot spring, which formed the center of the newly created Burtscheider Promenade . The spring catchment had to be expanded as early as 1854, as the spring water level fell due to the pumping of thermal water from the neighboring Karlsbad springs. From 1889 the water from the Victoria spring fed the drinking fountain in the foyer of the Kurhaus. With a daily pouring of 170 m³ after the Rethel spring (Rosenquelle II), the Victoria spring was one of the most abundant thermal water advances in Dammstrasse. After the Kurhaus, which was destroyed in the war, was torn down, the spring was sealed and is no longer used today.

The lower Burtscheider source group

In the area northeast of the railway viaduct in Frankenberger Viertel, a group of Quellvorbrüchen which about 30 are and unlike the sources in Burtscheid ° C cooler at the shore of the warm stream and Gilles creek as concentrating pond sources flew out. As early as 1829, Monheim mentioned that these springs are exposed to strong temperature fluctuations and changes in mineralization due to mixing with rainwater. Most of the springs are unused today, only the Mephisto spring was bottled by the mineral water industry until the end of 2009.

Snake spring

The source rises in the bank area of the Warm Bach, at the end of today's Römerweg. The spring was taken in 1874 and at that time had a temperature of 38–39 ° C. The source temperature currently fluctuates between 26 and 31 ° C. The total mineralization of the spring is 3.6 g / l and is still monitored at regular intervals today.

Smallpox (smallpox)

Located in the immediate vicinity of the snake spring, the spring has a similar overall mineralization. The spring was also taken in 1874. The name of the spring is derived from the use of the thermal water in the past to treat skin rashes. In this source, too, a decrease in temperature from 45 ° C (1810), over 37 ° C (1822) to the current 27–32 ° C can be observed over the last 200 years.

Source below smallpox

Located a few meters northeast of Pockenpützchen, this spring was also only caught in 1874 and at that time had a spring temperature of 38–39 ° C. Today this spring is also approx. 10 ° C cooler and has a total mineralization of 3.5–3.6 g / l.

Mephisto spring (concentration shaft)

The source shaft of the Mephisto spring was built in the run-up to the construction of the Schloss- and Luisenbad from 1872 to 1874. At that time it supplied the bathing hall of the castle baths and the baths of the Luisenbad with 38–40 ° C warm thermal water, which could be lifted out of the shaft by means of pumping stations if required. Today the Mephisto spring has a spring discharge of around 5 m³ / h, a temperature of 38 ° C and a total mineralization of 3.9 g / l and was bottled as mineral water by Mephisto Getränke GmbH until the end of 2009.

Garden spring

The garden spring rises in the immediate south-eastern bank area of the Gillesbach in today's Schlossstrasse. As a result of the construction work in connection with the development of the Frankenberger Quarter and the construction of the concentration shaft, the spring discharge has changed significantly. The 38–40 ° C warm garden spring today has a total mineralization of 4 g / l and is no longer used.

Meadow spring

The meadow spring rises on the northeast bank of the now canalized Gillesbach and is the northeasternmost source of the Burtscheider thermal water train. In the past it was only used as a house well for the surrounding houses. The spring had a temperature of 28–29 ° C at the beginning of the 19th century. Today it is no longer used.

Smaller, temporarily used sources

In Burtscheid there are numerous smaller, less productive thermal water springs that were only used temporarily in the past. These include near the Burtscheider market, the Kleinheiß, St. Sebastianusquelle and the Großheißquelle. In the past, they supplied, among other things, numerous running fountains on the market, which are now built over. In the 17th century, near the abbey gate, there was the women's bath, which was used by the abbesses of the Burtscheider monastery and fed from their own spring.

During the construction of the Burtscheid railway viaduct, a thermal water inlet with a temperature of 40 ° C was exposed in the area of the foundation of a pillar, which had to be laboriously sealed in order not to endanger the structure. To the south-east of the springs of today's rheumatism clinic, a smaller thermal spring was used for the bath salt and drinking salt production of Aachen's natural spring production at the beginning of the 20th century .

Furthermore, numerous smaller, 30–35 ° C warm springs are known in the bank area of the former warm brook in the Frankenberg district, none of which are accessible today.

Aachen thermal water route

In cooperation with the community foundation Lebensraum Aachen , an initiative was founded at the end of 2007 to draw attention to the existence and importance of the Aachen and Burtscheider thermal springs.

In addition to the identification of now invisible, mostly overbuilt sources, u. a. the former Prunkbad Fürstenbad from the Kaiserbad Aachen, which was preserved when the Kaiserbad was demolished and was transferred to the Burtscheider Kurpark Terraces in 1964, was made accessible to the public again for cabaret events. Educational projects accompany various activities, an interactive information column, which is set up alternately at different, mainly tourist locations, provides information about Aachen thermal springs and the spa culture. Sponsorships for individual sources and additional road signs are given. The aim of the initiative is to merge the individual locations of former bathhouses and springs into a thermal water route. The public is informed about the sources and spa facilities that were once important for urban development in various activities, such as the day of the open monument and the geotope .

In the next few years it is planned to bring the thermal springs back to life in various locations and to commemorate the almost 2000 years of use of the springs. Until the closure of the city history collection of the city of Aachen, Frankenberg Castle, in 2010, numerous exhibits related to the history of the baths in Aachen could be viewed there.

Geocaching routes already lead along the thermal water route in Aachen and in Burtscheid.

In 2013, a donation made it possible to build the new spring building of the Rosenquelle Burtscheid in the spa gardens. The building was realized according to a design by the architecture firm frey architekten . In a media station, the Aachen thermal water route provides information about the thermal springs of Burtscheid and the bathing culture of past centuries.

Famous spa guests

- 765 ff. King Pippin the Younger

- 768 ff., Emperor Charlemagne

- 1065 King Henry IV.

- 1190 Gottfried von Viterbo (around 1125–1191 / 92), imperial chaplain to Friedrich Barbarossas

- 1333 Francesco Petrarca (1304–1374) writer, historian

- 1431 Ludwig I (Hesse) , Landgrave of Hesse

- 1435 Pius II , Pope Nicholas V , Pope

- 1520 Albrecht Dürer , painter

- 1585 Nuncio Johannes Franz Bonomi

- 1680 Johann Wilhelm von der Pfalz , called Jan Wellem, elector and wife Maria Anna Josepha, Archduchess of Austria

- 1698 Anna Maria Luisa de 'Medici , Grand Duchess of Toscana, second wife of Johann Wilhelm von der Pfalz

- 1717 Tsar Peter the Great

- 1736 Karl Ludwig von Pöllnitz (1692–1775), writer and adventure traveler

- 1737 Georg Friedrich Handel , composer

- 1742 Friedrich II. (Prussia) , monarch

- 1746 Karl Josef Batthyány , Field Marshal General

- 1747 Karl Theodor (Palatinate and Bavaria) , elector

- 1762, 1767, 1783 Giacomo Casanova (1725–1798), writer and adventurer

- 1780 Gustav III. (Sweden) , monarch (incognito)

- 1789, 1790 George Augustus Eliott, 1st Baron Heathfield , British general, Gibraltar; Death during the cure at Gut Kalkofen

- 1791 August Ferdinand of Prussia with wife Luise, (incognito)

- 1792, 1802 Gottfried Herder , poet

- 1799, 1815, 1818 Ernst Moritz Arndt , poet

- 1804 Joséphine de Beauharnais , Empress, wife of Napoleon

- 1804, 1811 Napoleon Bonaparte

- 1809, 1810, 1811 Laetitia Ramolino , Napoleon's mother, Pauline Bonaparte , Napoleon's sister

- 1812 Hortense de Beauharnais , Napoleon's stepdaughter

- 1814 Field Marshal General August Neidhardt von Gneisenau

- 1814 General Carl von Clausewitz

- 1814–1815 Max von Schenkendorf , writer

- 1815 Field Marshal General Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher

- 1815 Friedrich Carl von Savigny , crown syndic, founder of the historical school of law

- 1817 King Friedrich Wilhelm III. (Prussia)

- 1818 Tsar Alexander I of Russia

- 1821 King Wilhelm I.

- 1823,1828 Johanna Schopenhauer , writer

- 1827 Achim von Arnim , writer

- 1850 Maximilian II (Bavaria)

- 1855 Prince Konstantin (Hohenzollern-Hechingen)

- 1856 Giacomo Meyerbeer , composer

- 1857 Franz Liszt , composer

- 1870; 1896 Friedrich von Esmarch , founder of the Samaritan system

- 1872 King Charles XV. (Sweden)

- 1880 Queen Marie Henriette of Belgium , Archduchess of Austria

- 1894 Lord Frederick Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts , Lord of Kandahar, Pretoria and Waterford, Field Marshal

- 1907 Sultan Ali Ben Hammud Ben Muhammed of Zanzibar

Eminent scientists and spa doctors

Only through the systematic research and description of the Aachen and Burtscheid thermal springs did the city gain the reputation of one of the most important centers of European bathing culture in the 19th century. In addition to physicians and spa doctors, numerous geologists have researched the origin and composition of the Aachen thermal springs in the past.

The first honorary citizenship was 1870 a. a. Awarded to the geologist Ernst Heinrich von Dechen by the city of Aachen for his services to optimize the output of the Kaiserquelle .

The most important pioneers of research into the Aachen thermal springs include:

- Franciscus Blondel , bath doctor (1613–1703)

- Gerhard Reumont , Badeinspector (1765–1829)

- Carl Georg Theodor Kortum , doctor (1765–1847)

- Friedrich von Hövel , politician and scientist (1766–1826)

- Johann Peter Joseph Monheim , pharmacist and chemist (1786–1855)

- Ernst Heinrich von Dechen , geologist and professor of mining science (1800–1889)

- Justus von Liebig , chemist, (1803–1873)

- Alexander Reumont , spa doctor (1817–1887)

- Bernhard Maximilian Lersch , spa doctor (1817–1902)

- Ignaz Beissel , geologist (1820–1887)

Legends and stories

Numerous legends have grown up around the hot springs since the very beginning. The most famous mythical creature, the Bahkauv (Bach calf), is a memorial in Aachen city center. The Bahkauv is said to have lived in the sewers ( Kolbert ) of the thermal pools and to have frightened and stolen revelers returning home at night. Even in the time of King Pippin, a monster is said to have lived in the Kaiserquelle. During his morning bath, the king is said to have surprised the monster one day and killed it with a sword after a fight. The whole bath is said to have been stained with the monster's blood. This legend is now associated with a red-colored microbe that occurs mainly in warmer water. The story that Emperor Karl's horse shied away from riding in a swampy area and that Karl then discovered the hot springs is one of the many legends.

In addition to legends, numerous tragedies and stories are associated with the thermal springs and baths. On July 6, 1790, George Augustus Eliott, 1st Baron Heathfield, the former governor and defender of Gibraltar , died at his residence at Gut Kalkofen after excessive internal use of thermal water. Already at that time, numerous spa doctors warned that drinking six to a maximum of 18 liters of well water, which was common at the time, could damage the health of the spa guests.

On May 7, 1836, the composer Norbert Burgmüller drowned in the Quirinusbad at the age of 26 as a result of an epileptic attack . His close friend Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy composed the Funeral March in A minor, op.103 , for his funeral .

In the same year, the 21-year-old Otto von Bismarck began his legal clerkship in Aachen. In 1837 the young Bismarck fell in love with the then 17-year-old English Isabella Loraine-Smith, who was in Aachen for a cure. From July to September 1837 Bismarck accompanied Isabella and her family on a trip through Germany; In doing so, he exceeded the granted leave and did not seek an extension. He gambled away large sums of money in the Wiesbaden casino , was persecuted by creditors in Aachen and applied for a transfer to the Potsdam Regional Council (which was also granted).

In October 1922 the future world chess champion Alexander Alekhine attempted a suicide in the foyer of the Cornelius baths ; Bath doctors quickly intervened and saved his life.

literature

- Alexander, Beissel, Brandis, Goldstein, Mayer, Rademaker, Schumacher, Thissen: Aachen as a health resort . Ed .: City administration Aachen. Carl Mayer , Aachen 1889 ( Internet Archive [accessed January 12, 2016]).

- Ignaz Beissel: The Aachener Sattel and the thermal springs that break out of the same . J. A. Mayer, Aachen 1886.

- Ignaz Beissel: The bathing and spa life of Aachen and the former Burtscheid in its historical development . In: Festschrift for the 72nd Assembly of German Naturalists and Doctors . Julius Springer, Berlin 1900, p. 81-117 .

- Franciscus Blondel : Detailed explanation and apparent miracle effect of their holy bath and drinking waters in Aach . Aachen 1688 ( MDZ-Munich [accessed on August 9, 2015]).

- Bruno Bousack: Hot springs - history and stories from Aachen . Meyer & Meyer, Aachen 1996, ISBN 3-89124-317-0 .

- Hans Breddin: New findings on the geology of the Aachen thermal springs . In: Geological communications . tape 1 , 1963, p. 211-237 .

- Hans Christ: The Carolingian thermal bath of the Aachen Palatinate . In: Germania . tape 36 , 1958, pp. 119-132 .

- Heinz Cüpper, Walter Sage, Gustl Strunk-Lichtenberg, Erich Meuthen, Leo Hugot, Joachim Kramer, Matthias Untermann, Walter Sölter , Dorothea Haupt: Aqvae Granni - Contributions to the archeology of Aachen (= Rhenish excavations. Volume 22 ). Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1982, ISBN 3-7927-0313-0 .

- Wilhelm Hofmann: The urban development of the bathing districts in Aachen and Burtscheid . In: Aachen contributions for building history and local art . tape 3 , 1953, pp. 180-248 .

- Friedrich von Hövel: A contribution to the knowledge of the mountains from which the hot springs in Aachen and Burtscheid emerge . In: Niederrheinische und Westfälische Blätter . tape 3 , 1803, pp. 43-61 .

- Christoph Keller: Archaeological research in Aachen (= Rhenish excavations. Volume 55 ). Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2004, ISBN 3-8053-3407-9 .

- Carl Georg Theodor Kortum : Complete physical-medical treatise on the warm mineral springs and baths in Aachen and Burtscheid . Heinrich Blothe, Dortmund 1789 ( GDZ Göttingen [accessed on August 15, 2015]).

- Bernhard Maximilian Lersch : The Burtscheider thermal baths in Aachen . M. Urlich's son, 1862.

- Justus von Liebig : Chemical investigation of the sulfur sources in Aachen . Anton Jakob Mayer , Aachen and Leipzig 1851 ( MDZ Munich [accessed on August 9, 2015]).

- Juliano de Assis Mendonça: History of the public limited company for spa and bathing operations in the city of Aachen 1914-1933 . In: Aachen studies on economic and social history . tape 9 . Aachen 2012, ISBN 978-3-8440-1520-1 .

- Joseph Ferdinand Michels: Treatise on the usability of the in the kaiserl. mineral waters located in the free imperial city of Aachen, in which it is shown the advantages with which they are used in various cases, with more than a hundred remarkable medical histories . F. N. Bourell, Cologne 1785.

- Johann Peter Joseph Monheim : The healing springs of Aachen, Burtscheid, Spaa, Malmedy and Heilstein, in their historical, geognostic, physical and medical relationships . Jacob Anton Mayer , Aachen and Leipzig 1829 ( MDZ-Munich [accessed on August 9, 2015]).

- Johannes Pommerening: Hydrogeology, hydrochemistry and genesis of the Aachen thermal springs . In: Communications on engineering geology and hydrogeology . tape 50 , 1993, ISSN 0341-3853 .

- Gérard Reumont : Aachen and its healing springs . A paperback for bathers. La Ruelle , Aachen 1828 ( MDZ-Munich [accessed on August 9, 2015]).

- Carl Rhoen : The Roman thermal baths in Aachen. An archaeological-topographical representation . Cremer'sche Buchhandlung, Aachen 1890.

- Manfred Vigener: Living water - the Aachen and Burtscheider thermal springs . Ecology Center Aachen V., Aachen 2000, ISBN 3-00-005619-X .

- Friedrich Wilhelm Leopold Zitterland: Instructions for well guests to successfully use the healing springs in Aachen and Burtscheid . J. J. Beaufort, 1830.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Leopold Zitterland: Aachen's hot springs - A manual for doctors, as well as an indispensable adviser for well guests . J. A. Mayer, 1836.

Web links

- Aachen thermal springs. City of Aachen, accessed on January 28, 2012 .

- Rita Mielke: bathing history. City of Aachen, accessed on January 28, 2012 .

- Aachen thermal water route. Civic Foundation Thermal Water Route Aachen , accessed on January 28, 2012 .

- Thermal water route Aachen - back to the sources. (PDF file; 742 kB) Accessed January 28, 2012 .

- Thermal springs. Community foundation Lebensraum Aachen , accessed on January 12, 2016 .

- Carolus Thermen - Bad Aachen - bathing tradition, history. Carolus Thermen Bad Aachen, accessed on January 12, 2016 .

- Bad Aachen - Enjoy the flow of the springs. Kur- und Badegesellschaft mbH, accessed on January 12, 2016 .

Individual evidence

- ^ J. Pommerening: Hydrogeology, hydrochemistry and genesis of the Aachen thermal springs . Aachen 1993, p. 153-154 .

- ↑ Friedrich Wilhelm Leopold Zitterland: Aachen's hot springs - A manual for doctors, as well as an indispensable adviser for well guests . Aachen 1836, p. 315 .

- ↑ Aachen thermal water route. (PDF; 1.0 MB) Retrieved February 1, 2012 .

- ↑ Christoph Keller: Archaeological research in Aachen . Mainz 2004, p. 28-31 .

- ↑ Andreas Schaub explains the archaeological findings at the court Archeology at the court. (MP3; 1.5 MB) City of Aachen, accessed on July 3, 2009 .

- ↑ Andreas Schaub explains the archaeological window in Aachen Cathedral Archeology in Aachen Cathedral. (MP3; 1.0 MB) City of Aachen, accessed on July 3, 2009 .

- ^ Andreas Schaub, Klaus Scherberich, Karl Leo Noethlichs, Raban von Haehling: Kelten, Römer, Merowinger . In: Thomas R. Kraus (Ed. For the city of Aachen and the Aachener Geschichtsverein eV): Aachen. From the beginning to the present . Volume I: From the natural foundations - from prehistory to the Carolingians . Aachen 2011, ISBN 978-3-875-19251-3 , p. 382ff.

- ↑ Andreas Schaub explains the archaeological window in the Elisengarten Archeology in the Elisengarten. (MP3; 1.4 MB) City of Aachen, accessed on July 3, 2009 .

- ^ Leo Hugot : Excavations and research in Aachen (= Rhenish excavations. Volume 22 ). Cologne 1982, p. 115-173 .

- ^ Wilhelm Mummenhoff: The years 1251–1530. Aachen 2003, p. 41.

- ^ Egon Schmitz-Cliever : The medicine in Aachen . Aachen 1963, p. 118-122 .

- ↑ Franciscus Blondel: Detailed explanation and apparent miracle effect of their Heylsamen bath and drinking water in Aach . Aachen 1688, p. 8 .

- ↑ Thomas R. Kraus: On the way to modernity - Aachen in the French time 1792/93, 1794-1814 . Aachen 1994, p. 610 .

- ↑ Leopold Zitterland: The newly discovered iron springs from Aachen and Burtscheid together with a message about the extraction of the thermal salts itself . JA Mayer, Aachen 1831.

- ↑ Alexander Reumont : The Aachen sulfur thermal baths in syphilitic forms of disease . Enke, Erlangen 1859 ( MDZ-Munich [accessed on August 9, 2015]).

- ^ Adam C. Oellers, Roland Rappmann, Anke Volkmer, Uwe Eichholz: The femme fatale at the pace of the big city - the master designer Jupp Wiertz 1888–1939 . Aachen 2004, p. 22 .

- ^ Wilhelm Hofmann: The urban development of the bathing districts in Aachen and Burtscheid . Ed .: Albert Huyskens (= The old Aachen - its destruction and its reconstruction ). Mainz 1953, p. 233-235 .

- ^ Walter Sölter: Roman sites in Aachen-Burtscheid (= Rhenish excavations. Volume 22 ). Cologne 1982, p. 205-213 .

- ^ Franz K. Wehsarg: Bad Aachen - Burtscheid . Stuttgart - New York 1979, p. 13 .

- ↑ Alexander Reumont: The thermal baths of Aachen and Burtscheid - according to occurrence, effects and type of application . Aachen 1885, p. 190-254 .

- ↑ Alexander Reumont: Bath salts for preparing the Aachen baths. In: The thermal baths of Aachen and Burtscheid - According to occurrence, effects and type of application. Aachen 1885, pp. 254-255.

- ↑ Ignaz Beissel: The Aachen saddle and the thermal springs that break out of the same. Aachen 1886, p. 211.

- ^ Andreas Schaub, Klaus Scherberich, Karl Leo Noethlichs, Raban von Haehling: Kelten, Römer, Merowinger . In: Thomas R. Kraus (Ed. For the city of Aachen and the Aachener Geschichtsverein eV): Aachen. From the beginning to the present . Volume I: From the natural foundations - from prehistory to the Carolingians. Aachen 2011, ISBN 978-3-875-19251-3 , p. 338

- ^ Wilhelm Mummenhoff: Regesten der Reichsstadt Aachen I. Aachen 1937/1961, p. 289.

- ^ Johann Peter Joseph Monheim : The healing springs of Aachen, Burtscheid, Spaa, Malmedy and Heilstein in their historical, geognostic, physical, chemical and medical relationships. Aachen and Leipzig 1829, p. 169 ( online ).

- ↑ Ignaz Beissel: The Aachen saddle and the thermal springs that break out of the same. Aachen 1886, p. 214.

- ↑ Bernhard Maximilian Lerch: About the productivity of the Aachen thermal springs. Aachen 1887, p. 7.

- ↑ Ignaz Beissel. The Aachener Sattel and the thermal springs that break out of the same. Aachen 1886, p. 217.

- ↑ Ignaz Beissel: The Aachen saddle and the thermal springs that break out of the same. Aachen 1886, p. 190.

- ↑ Bernhard Maximilian Lerch: Monographic sketch of the Burtscheider thermal baths. Aachen 1862, pp. 59-62.

- ^ Stephan Mohne and Oliver Schmetz: Schwertbad wants a new building on Jägerstrasse . In: Aachener Zeitung . ( aachener-zeitung.de [accessed on May 11, 2017]).

- ^ Stephan Mohne and Oliver Schmetz: Landesbadquelle is becoming a modern energy supplier . In: Aachener Zeitung . ( aachener-zeitung.de [accessed on March 27, 2018]).

- ↑ Ignaz Beissel. The Aachener Sattel and the thermal springs that break out of the same. Aachen 1886, p. 191.

- ↑ A. Pauels: Under eagle and swan - The chronicle of the mayor's office Burtscheid for the years 1814–1886. Aachen 1997, p. 244.

- ^ Johann Peter Joseph Monheim: The healing springs of Aachen, Burtscheid, Spaa, Malmedy and Heilstein in their historical, geognostic, physical, chemical and medical relationships. Aachen and Leipzig 1829, p. 226 ( online ).

- ↑ Ignaz Beissel: The Aachen saddle and the thermal springs that break out of the same. Aachen 1886, p. 194.

- ↑ Albert Huyskens: Hundred Years of Association for the Support of Unprofitable External Wells or Bathers at the Mineral Springs of Aachen and Burtscheid - Festschrift on May 10, 1935 . Aachen 1935, p. 31 .

- ^ Johann Peter Joseph Monheim: The healing springs of Aachen, Burtscheid, Spaa, Malmedy and Heilstein in their historical, geognostic, physical, chemical and medical relationships. Aachen and Leipzig 1829, p. 227 ( online ).

- ↑ Council Information System Acceptance of a Donation , accessed on March 25, 2013.

- ↑ Rosenquelle Burtscheid. City of Aachen , facility management, accessed on November 3, 2013 .

- ↑ Bernhard Maximilian Lerch: Monographic sketch of the Burtscheider thermal baths. Aachen 1862, p. 68.

- ↑ Ludwig Engels: From Alt-Burtscheid. From the Burtscheider baths in earlier times. In: Echo der Gegenwart , 4th edition (December 4, 1926).

- ^ Niels Peter Hamberg: Analysis of the Victoria fountain. Aachen 1862, p. 2.

- ↑ Ignaz Beissel: The Aachen saddle and the thermal springs that break out of the same. Aachen 1886, p. 199.

- ↑ Bernhard Maximilian Lerch: Monographic sketch of the Burtscheider thermal baths. Aachen 1862, p. 70.

- ↑ Ignaz Beissel: The Aachen saddle and the thermal springs that break out of the same. Aachen 1886, p. 200.

- ↑ Bernhard Maximilian Lerch: Monographic sketch of the Burtscheider thermal baths. Aachen 1862, p. 63.

- ↑ Ignaz Beissel: The Aachen saddle and the thermal springs that break out of the same. Aachen 1886, p. 197.

- ↑ Bernhard Maximilian Lerch: Monographic sketch of the Burtscheider thermal baths. Aachen 1862, p. 71.

- ^ Johann Peter Joseph Monheim: The healing springs of Aachen, Burtscheid, Spaa, Malmedy and Heilstein in their historical, geognostic, physical, chemical and medical relationships. Aachen and Leipzig 1829, p. 225.

- ↑ Aachen thermal water route - back to the sources. (PDF file; 759 kB) bs.xq-intern.de, accessed on February 25, 2012 .