Alfredus House

The Alfredushaus in Essen's old town was the club house of the Christian workers' association founded in 1870 . The association had a variety of functions for its members, in particular it served to represent the interests of their employers and state institutions. The building was primarily a workers' hospice , i.e. a sleeping quarters , and a meeting place. From 1897 to 1912 the People's Office was also set up there to help workers apply for the new Bismarck social legislation benefits . This was the first of its kind in Germany, which was soon followed by many others. Due to financial disagreements and, above all, political pressure, the association, which was close to the center , was dissolved in 1935. The house near the production facilities of the Krupp cast steel factory fell victim to Allied bombs in World War II .

The name Alfredushaus was chosen both in honor of the founder of the Abbey and City of Essen, Altfrid , and the founding son and owner of the Krupp company, Alfried Krupp , who died in 1887, ten years before moving into the house. The Latinized form of the word has been in line with contemporary tastes since humanism .

Church history environment

The Ruhr area is and was divided in many ways. For example, both parts of the Rhineland and Westphalia are part of it, two large areas in Germany that are characterized by quite different mentalities. It is also divided from a denominational point of view: Places that belonged to Kurköln or Vest Recklinghausen until secularization were traditionally Catholic, the lands of the Duchies of Berg and Jülich , which fell to Prussia in the 17th century , were dominated by Protestants. Industrialization did not change this character, even if it resulted in a faster mixing of denominations.

In the second half of the 19th century, the Catholic Church was in tune with the times: it channeled the sense of justice of broad sections of the population against the revolutionary ideas of 1789, but on the other hand it promoted their modern democratic demands. The Catholic association system can be used as an example. The Alfredushaus with all its activities shows this in an exemplary manner.

Catholic associations in the Rhineland

Many social innovations of this time come from the working class milieu with a Christian character, such as the founding of Christian trade unions or the Catholic workers' associations, whose predecessors, the Pius clubs , were formed with the events of the 1848 revolution. Since the end of the 1860s, referring to the ideas of the Bishop of Mainz, Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler , the first workers' associations emerged in Aachen, Elberfeld, Essen and Krefeld, which were headed by the spiritual president on the Lower Rhine. With 4,000 members, the Essen association was by far the strongest. In the Ruhr area, the workers' associations emerged as miners' associations with which the miners reacted to the loss of identity caused by the miners' union reform of 1854.

Initially based on religious motives, the associations quickly became politicized due to mass poverty ( pauperism ) to which a large part of their members was exposed through no fault of their own. Particularly socially committed priests were so quickly defamed as "red chaplains" by conservative church circles.

The first “mass strike”, which lasted from June 16 to July 28, 1872 and in which 26,000 miners went on strike, was organized by the associations. It is interesting to note that this strike did not pass into the eastern - that is, Protestant - district because the mine owners knew how to ostracize the rebels as "Jesuit strikers" in front of their own workers. This shows that denominational ties still outweighed membership of a common workforce.

In this early period, the club members were not only exposed to the mistrust of their bourgeois Catholics, they also had to deal with the state organs: In August 1874, the mayor of Essen, Gustav Hache, banned the workers' association "temporarily" until a judicial decision was made. Several members of the association were reported after house searches for violating the association law, but were acquitted in both the first and second instance.

In the opinion of the chief judge in the Hammer Trial in 1874, the "associations in the municipalities of the district were to be viewed as special associations, as branch associations of the Christian workers' association in Essen". Accordingly, the Essen association can be viewed as a kind of umbrella organization for the other Catholic workers' associations in Essen. An examination of this fact is no longer possible today, mainly because the associations avoided an entry in the association register because of the culture war (see below). The legal inability of the association was accepted.

| founding | designation | Number of members | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 1907 | 1908 | ||

| 1870 | CAV Essen old town | 1370 | 1047 | 900 |

| 1873 | KAV Rellinghausen | 150 | 158 | 155 |

| 1876 | CAV Rüttenscheid | nv | 500 | 480 |

| 1883 | KAV Holsterhausen | 106 | nv | nv |

| 1889 | KAV Altendorf | 560 | 1479 | 1539 |

| 1891 | KAV Huttrop (1) | 190 | - | - |

| 1893 | KAV St. Marien (Segeroth) | 310 | 371 | 457 |

| 1902 | KAV Holsterhausen (St. Mariae Conception) | - | 417 | 596 |

| 1905 | KAV Frohnhausen | - | 326 | 386 |

| 1906 | KAV Holsterhausen (St. Mariae Birth) | - | 385 | 539 |

| 1907 | KAV St. Andreas (Rüttenscheid) | - | 102 | 112 |

| 1907 | KAV Bergerhausen | - | 139 | 125 |

| total | 2686 | 4924 | 5189 | |

|

CAV = Christian workers 'association, KAV = Catholic workers' association;

(1)Huttrop was excluded in 1907 because the West German workers newspaper was not launched

|

||||

Dr. Franz Fink took over the management of the Essen Christian Workers' Association on March 1, 1901 and was amazed to find that there were no documents from his predecessor, Pastor Drießen, on resolutions, correspondence, contracts and so on. He replied: "For fear of harm, which makes one wise, as I was told, every suggestion on my part for written records was stubbornly rejected." What was meant was the time of conflict between the Kulturkampf and the clashes with the police and the judiciary. The subsequent period is documented again, but there are only a few primary sources for the early years.

At this climax of the Kulturkampf, a delegate from Essen to the General Assembly of the Socialist General Workers' Association in Berlin should be quoted: “ Priests are the most dangerous enemies of our cause, they come up with our program at the crucial moment and say: we want the same thing, religion just has to be preserved. "

The Essen association was one of the few who called themselves “Christian” rather than “Catholic”. Probably the idea was to be open to Christians of other denominations as well. However, this should have been difficult due to some paragraphs of the statutes:

"§ 3 Means to achieve this purpose

1.) Celebration of communion on two days to be specified, [...]

§ 5 Organization of the association

Management of the association: The association is headed by a Catholic clergyman appointed by the spiritual authority. [...] "

Catholic associations vs. Socialists

First of all, a brief consideration of the term “ socialism ” is necessary. As a counter-movement to capitalism and liberalism , he wanted to enforce social justice for the weakest sections of the population. These goals should also be achieved through class struggle or a revolution . After the first mergers in workers 'or trade associations in the middle of the century, Ferdinand Lassalle founded the General German Workers' Association (ADAV) as the first political party. This was united in 1875 with the Social Democratic Workers 'Party founded by Bebel and Liebknecht in 1869 to form the Socialist Workers' Party and in 1890 renamed the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), which still exists today. (Main article → History of the German workers' associations )

The party's actions were very aggressive and polarizing, which led to controversy with the Christian workers' associations. The conflicts were exacerbated because the Christian associations accepted state authorities, while the majority of the Marxist-oriented socialists wanted to force an overthrow.

The influx of Christian social groups (Catholics) can be explained by the mentality of the miners who, in the first generation, had to change their small-scale agricultural way of life to monotonous “colliery times”. She continued to cultivate her piece of land, her handful of chickens and the goat behind the house. In 1878, the SPD's predecessor, the Socialist Workers 'Party, had around 30 groups of workers with a total of around 2,300 members, while the Christian-oriented workers' associations had almost 230 groups with 46,000 members. The Catholic associations represented and dominated the workforce in the 1870s.

Associated with this, however, were reprisals such as the Krupp threat in 1878 to terminate all club members. Such and similar measures were always the result of demands for wage increases, reduced working hours, rest days and the like. or the prohibition of school-age children from factory work.

Political demands and their implementation

The issue of child labor has been a political issue for a long time that has caused displeasure. The Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs was unable to enforce its intention to reduce child labor in order to enforce compulsory schooling. It was not until 1837, when a Barmer factory owner again called for child labor to be restricted, that unexpected support came from the military , who were concerned about the health of the conscripts. So child labor could be prohibited for less than nine years old in 1839 and for more than nine years of school age will be set at ten hours, including breaks. In 1853 the minimum age was increased to 12 years, and for those under 14 it was reduced to six hours a day. Only now was a state factory inspection introduced to check compliance with the regulations. Further reforms in the Prussian trade law (1845 and 1849) resulted in the participation of workers in the local trade council, the invalidity of contracts on Sunday work and other health regulations.

From today's perspective, the achievements represented a continuous improvement in employee rights: The Health Insurance Act followed in 1883 , the Accident Insurance Act in 1884 , the Old Age and Disability Insurance Act in 1889, and finally the Employees Insurance Act in 1911 .

social environment

In the second half of the 19th century, the city of Essen was roughly the size of today's district I. The five districts of the north, east, south-east, south and west are grouped around the city center (old town) . The address of the Alfredushaus was Frohnhauser Strasse, which, towards today's Frohnhausen district , cut the west quarter almost centrally from east to west in two halves. In 1896 the population passed the 100,000 mark; Essen became a big city .

Urban development

| Districts | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 | 1925 | 1939 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | in 1000 | % | in 1000 | % | in 1000 | % | in 1000 | % | in 1000 | |

| City center | 14.7 | 18.7 | 12.8 | 10.8 | 10.2 | 2.5 | 7.7 | 1.6 | 7.7 | 1.1 |

| West quarter | - | - | 22.7 | 19.1 | 18.9 | 6.4 | 13.7 | 2.9 | 12.7 | 1.9 |

| other districts | - | - | 83.4 | 70.1 | 105.2 | 35.7 | 105.0 | 22.3 | 100.2 | 15.1 |

| Old town as a whole | 78.7 | 100.0 | 118.9 | 100.0 | 134.3 | 45.6 | 126.4 | 26.9 | 120.6 | 18.1 |

| other parts of the city | - | - | - | - | 160.4 | 54.4 | 344.1 | 73.1 | 546.1 | 81.9 |

| Food overall | 78.7 | 100.0 | 118.9 | 100.0 | 294.7 | 100.0 | 470.5 | 100.0 | 666.7 | 100.0 |

The table shows the population development of the city of Essen from 1890 to the census on May 17, 1939. The city center and Westviertel districts were of particular importance for most of the facilities located in the Alfredushaus. What is striking is the shrinking proportion of the resident population of these two districts in the city as a whole, which is almost insignificant.

“The area of the parish was bordered in the north by Limbecker Chaussee and Limbecker Strasse , in the east by the axis Lindenallee, Maxstrasse and Selmastrasse, in the south by the Bergisch-Märkische Railway to the city limits [...] In the official activities of Pastor Fink A shadow was already falling, which in the following time became more and more intense: the number of souls in the parish decreased. As a result of the expansion of the Krupp factory , entire streets were closed. Kanonenstrasse, Grüner Weg, half of Kniestrasse, half of the Westend Colony, parts of Frohnhauser Strasse and Schwanenkampstrasse, which all the active parishioners of St. Joseph had counted, disappeared ”. The map from the late 1920s clearly shows that at least two thirds of the municipality is already occupied by industrial areas.

In a report from 1937, the pastor wrote that the church, consecrated in 1869, was in the wrong place, too close to the Krupp factory. The number of souls has decreased from 8,000 when it was founded to three and a half thousand. In addition to the expansion of the factories, he mentioned, among other things, the conversion of living space into offices and business premises, road widening and breakthroughs as well as a lack of acceptance - i.e. vacancies - in old-style apartments without comfort. At the end of the Second World War , almost the entire district was destroyed, including the church, the tower of which was blown up in January 1957. The community still had around 200 people who were housed in seven houses. The community was dissolved.

Housing conditions

The living and working conditions of the early industrial era were shaped by rapidly growing employment and, consequently, population numbers. Statistically speaking, there were almost six residents per apartment in the city center. With a higher number of children then than today, this value does not seem excessively high. However, if you also consider the size of the apartment, the cramped living conditions quickly become clear: The number of rooms (including kitchen and attic) from 1900 and 1910 in the city of Essen is compared as an example. It is noticeable that the number of small apartments has decreased in these ten years. While the one-room apartments in 1900 had a share of 4 percent, in 1910 they were only just under 2 percent, while in 1900 the largest share with 35.5 percent was in the two-room apartments, in 1910 this shifted to the Three-room apartments with a 32.2 percent share.

For all major German cities of that time, nine tenths of the population lived in rented apartments. Some of these citizens even took in strangers with whom they shared a room and bed.

In this recording of people, the room tenants are to be distinguished from the sleepers . Room tenants had their own room, which they usually locked and where they could stay or receive visitors. “A sleeper has a place to sleep and accommodation for the night in a room that he often shares with other sleepers or members of the host family. He generally has his own bed, his own towel and usually his own washing dishes. Every four to six weeks she receives clean bedclothes, every week a clean towel. ”The occupancy number can be found in the table.

| Number People in a room | Number Sleeping people |

|---|---|

| in a group of four | 1042 |

| five people | 360 |

| to six | 198 |

| to seven | 94 |

| to eight | 64 |

| to nine | 24 |

The statistical figures from 1900 do not reveal the extent to which several sleepers share a bed. Although banned for a long time, house inspections repeatedly found that sleepers of different sexes shared a bedroom.

| Districts | Households December 1900 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| without resident | Room tenants | Sleeping people | both | All in all | ||

| City center | 1,673 | 240 | 194 | 8th | 2.115 | |

| East quarter | 4,397 | 345 | 406 | 16 | 5,164 | |

| North quarter | 5,732 | 122 | 764 | 3 | 6,621 | |

| West quarter | 3,493 | 199 | 616 | 14th | 4,322 | |

| Südviertel | 3,255 | 469 | 151 | 17th | 3,892 | |

| Southeast quarter | 1,412 | 27 | 81 | 1 | 1,521 | |

| Sum city of Essen | 19,962 | 1402 | 2212 | 59 | 23,635 | |

| Altendorf | 12,428 | 175 | 387 | 9 | 12,999 | |

| Total food | 32,390 | 1577 | 2599 | 68 | 36,634 | |

The author of this statistical report, Otto Ludwig Wiedfeldt , even before his time as city councilor, devotes himself in the final chapter in detail to the requirements to improve the standard of the so-called after - tenants in terms of financial, moral and hygienic conditions. His recommendation were English-style public lodging houses .

The oldest private dormitory in Essen, the Krupp'sche Menage , was built in 1856. Initially designed for 200 people, the number of residents was over 1,000 in 1900. The accommodation including lunch and dinner was 24 marks. “At these prices, the menage can only exist without direct loss if there is strong participation (mandatory logging in for unskilled unmarried workers without an attachment); the company waives interest and amortization ”.

Single homes for women had existed in Essen for a number of years and had had a positive effect on the sleeping space for this group of people. The problem was the growing number of male sleep-seekers. A larger number of private providers were out of the question, as no return could be generated in the foreseeable future and the impairments within the apartment were usually viewed as too great. The city administration and also non-profit organizations saw their duty to provide relief.

This gives the main reasons that led to the establishment of the workers' hospice Alfredushaus in 1897 .

Tasks of the association

There were 27 years between the founding of the association and the move into an own club house. Only on February 2, 1897 could it finally be opened.

The idea of founding the association is primarily based on the idea of caring for the non-resident Christian workers who eke out their lives in sometimes inhumane conditions. One of the main initiators was Mathias Wiese , who was one of the founders of the Essen Center Party in 1870, the year in which the Christian Workers' Association was founded. Incidentally, in 1870 the foundation stone was laid for Villa Hügel , the Krupp private residence in Essen-Kettwig .

His financial independence as an entrepreneur made it possible for Wiese to risk state reprisals because he was subjected to police summons and house searches . The religious-charitable starting point, as it was the focus of German Catholicism in the 1850s, changed at the beginning of the 1860s. Above all, the Mainz Bishop von Ketteler, who in his speeches and writings spoke out in favor of a union organization of the workers based on the English model, was the driving force behind many committed Catholics like Wiese . Wiese himself was a committed member of the "Standing Section for Social Issues", which was first set up on the 1869 Catholic Day in Düsseldorf. This circle had the goal of founding Christian-social associations for the betterment of the working class. The association was founded by Kaplan Klausmann on Mariä Lichtmess in 1870. The statutes wrote about the reasons:

Ҥ1 The main purpose of the association is the religious and moral improvement of the working class, based on the idea that the social question can only be solved through Christianity. Another purpose of the association is the material improvement of the working class; Among other things, the association members who have come into poverty through no fault of their own are to be supported, as far as the association's treasury allows.

§2 We strive for this purpose: a) through pleasant and useful entertainment, through public lectures on non-profit and social issues at least once a month, through reading appropriate writings, singing and through the enjoyment of happy Christian company; b) through mutual and helpful intercourse in civil life. "

And in § 9 it said: "The Praeses should always be a Catholic clergyman."

The time before the Alfredus house

In the early years the Christian Workers' Association was very popular. As early as 1874 it had 3,000 members. That year Kaplan Klausmann was transferred to Cologne. He was succeeded as president of the association Kaplan Laaf, who was previously in Aachen and there as an employee of Kaplan Kronenberg in 1869 co-founded the “workers' association of St. Paul”. Laaf came at a difficult time: On August 4th, the Essener Blätter published a letter from the Lord Mayor with the message that the “Christian workers' association will be temporarily closed pending a judicial decision”. In addition, elsewhere on the same sheet of paper there are reports of house searches in the chaplain’s apartment and in the club premises of the Christian Workers’s Association: “All documents and books relating to the association, such as lists of members and minutes, etc., were seized. The lockers in the club's premises were opened by a locksmith requisitioned by the police. "

Another, politically less dangerous paper has survived to this day: the policy of the fire insurance company Rhineland . With their help, it is still possible today to determine the changing club premises for the period before moving into your own house. This policy lists the items that are insured. In the period from 1882 to 1892 the association resided at Steeler Strasse 10. The workers' association had two rooms, of which the larger was called the "theater hall". According to the insurance policy, the smaller one contained four cupboards, two desks, a theater cloakroom, books, song books and a violin as well as six flags. The owner of the house was the widow Kratz, who ran the hotel-restaurant "Kaiser Friedrich" in the neighboring house No. 8.

From 1892 to October 1895, the location at Kastanienallee 95 was held, where Carl Rothe ran the inn and restaurant “Zur Rothenburg”. The 25th anniversary celebrations took place there in May 1895. The last domicile before moving to his own “Alfredushaus” was at Varnhorster Strasse 7 with the religion teacher Josef Prill. Presumably this was a temporary solution until the club's own house was completed.

In the Alfredus house

For better management of the house and probably also because of questions of liability , the "Alfredushaus Aktien-Gesellschaft" was founded in advance - more precisely on June 19, 1896. The initiator was the religious teacher Carl Oberdörfer, who in May 1896 called for the establishment of a workers' hospice and for enough space to be created for the people's office. He did not fail to refer to the workers 'hospices that had been successfully established by Catholic workers' associations in the Rhineland over the past ten years: “These companies are very profitable.” - “Should you be inclined to invest in one or more shares in the company , we ask you to fill out the attached subscription form and send it back to the address below within 8 days. The Christian workers' association will make it their business to reward your kindness with gratitude and do everything possible to be able to grant you the 4% interest specified in the statutes.

God bless the Christian work! The preparatory committee, religion teachers Oberdörfer, z. Z. President of the Christian Workers' Association ”.

| Occupational group | number | composition |

|---|---|---|

| Workers | 4th | Disabled people, factory workers, pensioners |

| Master d. Craft | 9 | Bakers, plumbers, saddlers, locksmiths, butchers, watchmakers |

| Merchant | 13 | various |

| Teacher | 5 | Teacher, religious and senior teacher, rector |

| Entrepreneur | 6th | Building contractor, brewery owner |

| other jobs | 8th | Pharmacist, architect, court taxator, photographer, legal counsel, rendant |

The share capital amounted to 50,000 marks in denominations of 200 marks. According to the law of the General German Commercial Code (ADHGB) at the time , a denomination of 1,000 marks was provided for stock companies, but lower amounts were permitted for non-profit companies under certain conditions, but at least 200 marks. The shares had to be made out in the name of the owner and could only be sold with the consent of the company. It was also possible that several people shared a share, even if it was then issued to a bearer. As a start-up for this project, the workers' association participated in the stock corporation with a "larger amount". The notarial articles of association lists 45 names, 38 of which became shareholders, the management board consisted of ten people, the supervisory board was four people. The founders - all men - give a representative cross-section of the social stratification of the active club members (see table).

In 1897 the young company acquired the houses at Frohnhauser Strasse 19 and 21. The larger of the two, No. 19, was a new building from 1891, which was planned from the outset as a restaurant and equipped with a large hall in the rear part of the building meetings had occasionally been held before. The property went through the block and bordered the parish garden on Ottilienstraße opposite the St. Josef Church.

Even before the company was founded, successful talks had been held with the Rheinische Girozentrale and Provinzialbank , Düsseldorf (predecessor of the Westdeutsche Landesbank ), which made the remaining assets available at a favorable interest rate.

The workers' hospice and clubhouse are presented in detail in the partnership agreement. The so-called economist - nowadays probably referred to as the managing director - occupies the central figure of the company. As a hospice, the house was something like a hotel. According to § 2 of the partnership agreement, the purpose of the company was u. a .: "3. The procurement of the means and all the conditions for the management of these two, which, as far as they required a license are to be made on behalf of the Company by an economist ... "

This must have been a major mistake in the company's structure that led to the early financial difficulties. Outside of sales requiring a license, the shareholder should hardly have had the opportunity to generate his own sales. The management board's control over this man, as he is called elsewhere in the business papers, castellan , was very limited. After all, all board members were volunteers and each had their own business. In 1901 the castellan was replaced by an independent tenant. 1901 was also the year in which the community Frohnhausen , previously part of the independent mayor's office Altendorf, which with around 66,000 inhabitants was the largest Prussian rural community, was incorporated into the city of Essen.

The economic situation of the company was overwhelming in the first few years (until around 1913) and was mainly caused by the high level of borrowing when it was founded. In addition, constant police checks were obstacles that hindered the business.

Overall, the Aflredushaus had AG loan record in the amount of 200,000 marks; a considerable amount of money required for interest and repayment. The regularity of these payments left a lot to be desired and despite repeated reminders from the financial institution and many promises made by the debtor, little changed in the period up to 1913. It amazes the long-suffering of the believer. An early bankruptcy could only be prevented through the generosity of the friends and patrons of the Alfredus House .

The association reached one of several low points with a letter from the State Insurance Company of the Rhine Province of April 25, 1905 to Pastor Dr. Franz Fink, the president of the workers' association:

“We are informed by the General Praeses of the Catholic Journeyman's Associations in Cologne that your Reverend is particularly interested in social affairs, especially those of the Catholic workers' associations. We sincerely ask you to subject the following matter to a pleasant examination: […] The capital and interest rates are to be paid semi-annually on June 30th and December 31st of each year. In the past few years, however, the capital and interest rates have rarely been received on schedule, despite the fact that a delay of more than 1 month after the due date requires termination and immediate repayment of the capital. The threat of dismissal had to be used repeatedly. A personal consultation and inspection by a member of our board of directors on September 1, 1902 did not result in any change, despite the acceptance and also led to the unpleasant perception that the hospice was neglected and unclean, necessary repairs were not carried out, the hospice was operating in the most usual manner, etc.

The capital and interest rate of a total of 4,562.59 marks due on December 31, 1904, was also not received. The repeated reminders on this side, in which the capital termination was promised, even went unanswered. A visit then on March 24, 1905 by a local board member under the guidance of the chairman, Mr. Nürnberg, unfortunately revealed an extraordinary neglect, an increased need for repair of the buildings, utility rooms, the inventory, uncleanliness, etc. The economy operated in the hospice (beer, liqueur, etc. ) and the dormitory rental is leased to the caretaker for 1,000 marks a month, the utility rooms are on the ground floor, completely gave the impression of a normal economy with standing beer, etc. The chairman, Mr. Nuremberg, promised to send in the due rate immediately; as this had not yet been received on March 29th, we felt compelled to terminate the capital and on March 30th commissioned the lawyer Hennecke in Essen with the immediate execution . [...] "

The installment was then paid immediately and a guarantee from the Nuremberg Management Board was offered, but the insurance company considered it to be insufficient. Instead, they proposed that a more efficient association such as the parish join as guarantor.

The various police authorities, the regulatory police, the construction police, the trade police and other administrative authorities, tasks that were all carried out by the police at the time , were often present in the Alfredushaus on the official side. In 1902, according to a note from the Darmstädter Police Commissioner, the economic area was changed in an inadmissible manner. By setting up a tall bottle cabinet and a second bar table, as well as removing tables and chairs, a large part of the guest room had been changed into a standing beer hall (schnapps hall). The landlord did not respond to the initially verbal request to restore the old building condition. Only the threat of a possible closure of the restaurant within 14 days brought about the compromise to re-seat the dining room and to put the counter so close to the window that street sales became possible.

The economic reports of the early years chronically run through the undercrowding of the hospice and the landlord's complaint that he is no longer able to pay rent. In the opinion of the Executive Board, the large hall was also underutilized. Subsequent renovation work did not help much.

Workers hospice

One of the main reasons for buying the house was to set up a workers' hospice. In this way, the church was able to influence parts of the workforce with regard to the “dangers to religion and morality, especially for single, unmarried workers who had moved in from outside. ... All too often a social-democratic family that has broken down with faith and morality also offers him accommodation. The sad conditions that result for the family cannot be described here - only reference should be made to the surprisingly large number of divorces in a city, which is explained in the boarder system. "This actually correct description of the condition states the living conditions in Essen's old town (cf. . Chapter. Housing ). There were contradicting opinions on this matter: “If you believe the writings of bourgeois reformers, it is a question of a single sin babel and the loss of all culture. As a rule, however - as far as autobiographies, reports and interviews can be found, this kind of coexistence seems to have been possible without too much problems. "

In the cover letter to the city of Essen for a liquor license application on January 15, 1897, among other things, it says: “The importance of such a company, especially in the part of the city that is mainly inhabited by workers, should be obvious. It is in the moral as well as in the social interest to limit the boarding system as much as possible with its many dangers and pernicious consequences for family life. In the house mentioned, 100 workers are supposed to receive board and lodging, a larger number besides these daily lunch and dinner. In particular, we would like to draw your attention to the fact that with this undertaking, the large hall at Frohnhauser Strasse 19 will forever be withdrawn from all use of social democratic and similar agitation.

About a year after the house opened, a detailed article appeared on the Alfredushaus workers' home , as it was now called. The rapporteur cannot hide his amazement at the establishment:

“The house is initially the home of the Christian workers' association in Essen, which holds its fortnightly meetings there, for which the large hall with its magnificent ceiling light is all too suitable. But the hall is not welcome to the workers' association alone, but to all other larger Catholic corporations. A large hall serves as a dining room, and we have heard that around 200 workers are supposed to have an excellent lunch there every day at cheap prices. Next to it is the business room for the young people who have board and lodging in the home. Next to it is the library and study for the young, unmarried workers. Here you have the opportunity to read completely different Catholic newspapers, which the management of the People's Office, which is known to be in the annex building of the house, makes available free of charge. The facility here is remarkable: every young man has his own lockable compartment in which he can keep his utensils. Large work tables and a large library cabinet complete the furniture.

The beds are on the 2nd and 3rd floors. We were surprised by the great cleanliness. Iron patent beds with good bedding, a wardrobe, tables and chairs for everyone - a student in the city of museums couldn't ask for a better one. A separate room serves as a washroom and toilet room with beautiful faience basins, water pipes and a towel cabinet for everyone. The whole house was pleasantly warmed by a well-functioning steam heater.

With such an arrangement it is of course inevitable that the house will succeed. The management is subordinate to the workers' president Kaplan Boventer, who visibly tries to create a pleasant house for the young people. From last year's annual report it can be seen that the expectations of the shareholders have not been disappointed. The percentage promised when the house was founded has not only been reached, but exceeded. For the further development of the house it would certainly be desirable if more Catholic citizens turned their attention to it. [...] With that, he would not only have the prospect of having invested his money well, but also the knowledge that he was at the service of a useful cause. "

This optimistic assessment of the company's economic situation should soon be refuted. The sleeping places mentioned in the newspaper article were not accepted as expected. As early as 1905, offices for the Christian trade unions were set up on the third floor. The importance of the house as a bedroom will have steadily declined from the beginning. In the photo of the house from before 1910, there is no mention of the hospice. Whether it still existed at that point can no longer be estimated from the sources. The occupancy figures given in the Essen address books on a given date only permit limited conclusions to be drawn about the lodging guests present during the year. But the occupancy numbers continued to decline here as well: 1900: 40 people, 1901: 19, 1902: 12 and 1903: 6. In the years that followed, no people were recorded in the address books. This facility will no longer have existed by 1912 at the latest.

The decline was foreseeable: On the one hand, the Krupp company (see above) was very active in housing construction. The workers there paid 80 pfennigs a day for board and lodging, and 1.60 marks per day in the Alfredus house. Nevertheless, the house did not cover its costs, especially caused by mismanagement (see above).

People's Office

“It is advisable to meet facilities at industrial sites which are supposed to give the workers advice and information on how to effectively protect their rights. Such facilities should, if possible, be based on existing associations, possibly based on existing organizations ”. The Katholikentag in Koblenz in 1890 also dealt with questions about the new socio-political legislation. In the same year in which this report on the results of an event was created, the People's Office Association and the first People's Office in Germany opened in Essen , the establishment of which served as a model for many who followed. In 1897 the club's headquarters changed to the Alfredushaus. The activity was financed by association contributions.

During this period, the number of inquiries rose from 1,528 to 22,823 and the number of pleadings from 367 to 5,580.

The Essener Volkszeitung wrote about the general assembly that took place on December 18, 1899: “The People's Office primarily represents the people in their legal claims, which they make on society in economic terms; Secondly, it takes care of the poorest, who, beyond the scope of legal claims, are dependent on Christian charity. The People's Office introduces the numerous, not easily understandable provisions into practical life and makes a powerful contribution to balancing out social differences. It goes without saying that from this point of view his work must appear socially reconciling ”.

The diverse work that the People's Office carried out for its members is exemplified by a report in the Essener People's newspaper from February 1902, to which workers are entitled to pensions in the event of industrial accidents.

The office was in Frohnhauser Strasse 21 and consisted of the manager's room, the office, which also housed the registry, and the waiting room, in which newspapers were displayed. By a decision of the board of directors, poor people from the Essen city area were allowed to use the office's help without payment. This corresponded to the wish of Pope Leo XIII. , who in his well-known encyclical u. a. had called for the expansion of welfare institutions . The Essenes were particularly pleased that he mentioned the people's offices.

With the changes to the division in the Alfredushaus, the people's office operated from 1912 at Jägerstraße 16, which was also in the municipality of St. Josef , from 1928 the office then moved to Hindenburgstraße 52, the private home of the then head Blum.

Catholic Workers' Secretariat

In 1908 at the latest, the Catholic Workers' Secretariat , founded on November 1, 1903, also moved into the Alfredushaus, after it had previously been located at 19 Vereinsstrasse. This secretariat is to be understood as an umbrella organization for all Catholic associations. His tasks were correspondingly diverse. Internally, services with professional competence, training and representation rights were important for its members; externally, the organization knew how to assert its influence on local politics, commercial jurisdiction, administration and other institutions. Its head was Christian Kloft , from 1919 a member of the constituent Prussian state assembly and then (1921–1932) a member of the Prussian state parliament for the Center Party for three legislative periods .

The aforementioned right of representation also included the negotiation of collective agreements , which was first concluded with the building trades in September 1903. The Mayor of Essen, Erich Zweigert , had a great deal of self-interest in the collective bargaining of the secretariat, as in the past municipal buildings had repeatedly not been completed on time because wage wars had broken out in the construction industry . He suggested that the parties to the collective bargaining meet in November 1904 for a meeting under his leadership in the town hall in order to find a mutually viable solution. In addition to some city officials, the committee was made up of two representatives each from the employees and the employers. In addition, one representative each from the Christian trade unions (represented by Christian Kloft) and the trade union cartel were at the negotiating table. This occupation makes it clear what position the Catholic Workers' Secretariat already had shortly after it was founded.

In a new collective bargaining dispute in the bricklaying trade due to a breach of contract by the employer in the summer of 1905, Zweigert applied to the liberally dominated city council for 20,000 marks to be made available to support construction workers in need. Against the resistance, the city councilors reached Dr. Johannes Bell and Kloft transferred the application to the social commission, which then took place under the direction of the alderman Otto Wiedfeldt . On August 31 of the same year, the application was approved and the industrial peace restored. Triggered by this conflict, the Unification Office was founded in Essen in 1905, which consisted of five members from each of the two collective bargaining parties as well as the impartial assessors Otto Knaudt, smelter at Krupp, and Christian Kloft. Its scope covered 36 cities and towns in the industrial district.

Christian unions

The foundation for the founding of Christian unions outside of mining was laid at Whitsun 1899 in Mainz . At the congress that met there, the advocates of politically neutral, interdenominational trade unions, whose task it should be to represent the economic interests of workers, prevailed. The first union for the construction and woodworkers was founded in December 1899, that for the metalworkers followed in May 1900. The first local group was constituted in Essen-Altendorf , in 1901 in Essen-Stadt and in Bergeborbeck . The reason for the delay in relation to the construction and woodworkers was the "patriarchal system that existed among the metalworkers, which, combined with the welfare institutions, had prevailed in Essen for many years. Added to this was the fear of harm in the employment relationship caused by previous events "

In addition to the union secretariat described above, the following unions were also located in the Alfredushaus:

- Christian Social Metal Workers Association of Germany, Essen Paying Office (from 1910: Christian Metal Workers Association of Germany), Managing Director: Heinrich Hirtsiefer

- Central Association of Christian Builders, Essen Pay Office, with the sections

- Section of the Krupp masons

- Section of the construction workers

- Section of the roofer,

- Section of the cleaner

- Section of the stone workers

- Section of the carpenters

- Only the two sections of plasterers and tilers had other offices and meeting rooms.

- Home workers union, Essen local association

- Central Association of Christian Woodworkers

From 1918 the trade union secretariat was renamed the union cartel of the Christian unions for Essen and the surrounding area . The first secretary had been Heinrich Strunk since 1912 and now called himself antitrust secretary, while Christian Kloft was chairman until 1919.

From 1919 the seat of the cartel is at Limbecker Platz 26. The district association of the food and luxury food industry workers and the trade association of German bricklayers stayed in the Alfredushaus until 1928. The reasons for moving out are not known, as the meetings continued to be held at Frohnhauser Strasse 19 until the “bitter end” in 1933 .

The Alfredus House as an economic factor

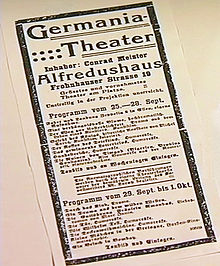

From 1909 the landlord, Conrad Meister, opened a cinema in the great hall that he called the Germania Theater . Approval took place on April 2, 1909 and was set to 488 seats. At a time when electrical lighting was still in its infancy, Meister also applied for the operation of a "power supply system" in order to be independent of the public supply. This movie was on April 5, 1923, during the Ruhr struggle , communists stole the box office. People were not harmed. The Germania Theater closed in the spring of 1932 and, after extensive renovations, was reopened as City on August 27 of the same year by City-Theater GmbH .

Since January 1896, before the founding of Alfredushaus AG , one of four Essen branches of the Kaiser's coffee shop in Viersen had been located in the neighboring house No. 21 . In July 1910, the business moved to house number 23. After this long rental period, there was a period of frequent changes: First, the hairdresser Lüttkemeyer is listed in the Essen address books as the tenant, followed by a rubber sole branch from 1916. The independent businessman Wittemeier then ran his business there until 1928, before Conrad Meister ran a liquor business there until 1932. With the change of ownership of the cinema in the great hall of house no.19, the entrance was moved to house number 21 because the trade supervisory authority found the old entrance between no.17 and no.19 to be too narrow for fire safety reasons.

The last general assembly took place on July 23, 1935. In it, the "conversion of the stock corporation by transferring the assets to the main shareholder [...] and approval of the conversion balance sheet " was resolved: "After a previous discussion and resolution, the assets of the Alfredushaus corporation including the debts were transferred to the main shareholder restaurateur Conrad Meister in Essen under liquidation. "The dissolution of the company was also made easier by the new commercial code , after the stock corporations were considered too small and anonymous and were no longer sought:" In order to facilitate the abandonment of anonymous forms of capital for entrepreneurial responsibility in appropriate cases, the Reich government has the following law decided [...] "This conversion rule is incompatible with the currently valid conversion law to be confused.

The house and the neighboring houses had not survived the destruction of the Second World War around the Krupp factory premises. Today there is a modern administration building there.

literature

There are still some files about the Alfredushaus in municipal and state archives. With the assumption of office by President Dr. Fink - as described in the chapter on Catholic associations in the Rhineland - papers on business transactions were archived again. There are also numerous newspaper articles in the Essener Volkszeitung as well as a number of event advertisements in the same.

Secondary literature is far less available. An attempt was made to collect all available sources under individual references . The most important work is undoubtedly:

- Friedrich Lantermann: Reports and contributions of the department for social and universal church tasks . Issue 29. Episcopal General Vicariate Essen, Essen 1996.

All other works devote only short passages or a small mention to the subject.

Individual evidence

- ↑ compare this: without author: "Our position on the miners' union reform", presumably. Ed .: Union of Christian Miners in Germany, Essen, approx. 1911, p. 4 and Gerhard Pomykaj: Miners' Movement and Social Democracy on the Ruhr before and after the strike of 1889 (PDF; 725 kB)

- ↑ According to the mass strike debate, this strike is unlikely to have been a mass strike. The term mass strike was adopted from the source given.

- ↑ Vera Bücker: Catholicism in the Ruhr area: http://www.kirche-im-ruhrgebiet.de/KIR/04%20Katholizismus%20im%20Ruhrgebiet.pdf

- ↑ a b Report by the Catholic workers secretary in Essen-Ruhr. 'Der Volksfreund' GmbH, formerly. FJ Halbeisen, Essen 1909, p. 5.

- ^ A b c d e f g Friedrich Lantermann: Reports and contributions. of the department for social and universal church tasks, Episcopal General Vicariate Essen, volume 29, Essen 1996.

- ↑ a b quoted from Heiner Budde, "Die Roten Kapläne", Cologne 1978, pp. 3 and 7

- ↑ Essener People's Newspaper of December 2, 1935.

- ↑ Josef Weier: The rise and fall of the parish of St. Joseph. In Das Münster am Hellweg, issue 1/2 1980, pp. 79f. Weier writes (footnote 219) about the figure of 8,000 parishioners mentioned in the report: The number is incorrect. The maximum number of souls in the parish of St. Joseph was 5927; see Handbook of the Archdiocese of Cologne, 19th edition Cologne 1905, p. 21.

- ^ Wilhelm Lucke: St. Josephskirche Essen-Altstadt, your becoming-work-offense. In: Das Münster am Hellweg, bulletin of the Association for the Preservation of the Essen Minster (Münsterbauverein e.V.), issue 7/1957, p. 85.

- ^ Statistics of the city of Essen; Statistical years 1900 and 1910, Jhrg. 3–41, p. 26.

- ↑ a b c City of Essen, Contributions to the statistics of the city of Essen, volume 7, The after-rental system in the city of Essen after recording on December 1, 1900. Edited by the statistical office on behalf of the mayor. Essen 1902, p. 20ff.

- ↑ without author: Welfare institutions of the cast steel factory von Fried. Krupp zu Essen ad Ruhr, 3rd edition 1902, Volume I, p. 28ff .; quoted from 'Statistics of the City of Essen'

- ↑ http://www.digitalis.uni-koeln.de/Krupp/krupp148-157.pdf House rules for the menage.

- ↑ Michaela Bachem-Rehm: WIESE, Mathias. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 27, Bautz, Nordhausen 2007, ISBN 978-3-88309-393-2 , Sp. 1541-1547.

- ^ Emil Ritter: The Catholic Social Movement and the People's Association. Cologne 1954, p. 73f.

- ^ Report on the Catholic Workers' Secretariat in Essen, Essen 1909, p. 8.

- ↑ Münster archive, files of the association (B641.3)

- ↑ Main State Archives Düsseldorf, RGNr. 243/96

- ↑ Münsterarchiv B 641.3 (F 6), accessed May 13, 1896.

- ↑ Franz-Josef Brüggemeier , Lutz Niethammer : Sleepers, Schnapps Casinos and Heavy Industrial Colony, Aspects of the Workers Housing Issue in the Ruhr Area before World War I. In: factory, factory, after work. Contributions to social history in the industrial age. Ed. by Jürgen Reulecke and Wolfhard Weber, Wuppertal 1978, p. 153.

- ↑ City of Essen, inventory XIV, No. 409, p. 50f

- ↑ without author: Welfare institutions of the cast steel factory von Fried. Croup to eat a. d. Ruhr, 3rd edition 1902, Volume I, p. 28.

- Jump up ↑ without author: Report of the Catholic Workers' Secretariat in Essen Ruhr, Essen 1909, p. 58.

- ^ Thomas Weber: Germany. The order of legal advice in Germany after 1945: from the Legal Advice Abuse Act to the Legal Services Act. Verlag Mohr Siebeck, 2010, ISBN 978-3-16-150378-8 , p. 186.

- ^ Frank Bajohr : Between Krupp and Commune. Social democracy, workers and city administration in Essen before the First World War. Essen 1988, ISBN 3-88474-122-5 , p. 31ff.

- ^ Annual report of the People's Office from 1897/98

- ↑ Essener People's Newspaper of December 19, 1899.

- ↑ Essen People's Newspaper. February 18, 1902.

- ^ Klaus Rohe: The Ruhr area social democracy in the Wilhelminian Empire and its political and cultural context. In: Gerhard Ritter (Hrsg.): The rise of the German labor movement. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 1990, p. 319f.

- ^ Address books of the city of Essen

- ↑ Müsterarchiv B 641.3 (F22)

- ^ Essen address books 1908, SI / 68

- ^ Contributions to the history of the city and monastery of Essen, 1958, pp. 25f.

- ↑ a b Report of the Catholic Workers' Secretariat in Essen-Ruhr: 'Der Volksfreund' GmbH, formerly FJ Halbeisen, Essen 1909, p. 20ff.

- ↑ Michael Schäfer: Heinrich Imbusch. Christian union leader and resistance fighter, Munich 1990, p. 25.

- ↑ Address books of the city of Essen, various years

- ↑ City of Essen: 15869, house files Frohnhauser Straße 19–21, Volume 1 (1867–1928), application for permission to install a cinematograph, pag. 216

- ^ Friedrich Lantermann: Essen cinema theater. From the beginnings to 1939, in: Contributions to the history of the city and monastery of Essen, edited. from the Historical Association for City and Monastery Essen eV 104th issue, 1991/1992, p. 229, note 136

- ↑ Essener People's Newspaper, August 27, 1932.

- ↑ Kaiser's coffee shop (ed.): 1880–1980 - 100 years of Kaiser's (anniversary publication)

- ^ Letter from Kaiser's in the possession of the author

- ↑ Münster archive, files of the association B 641.7 (F 19) Schäfer letter to Kaplan Plog dated June 24, 1929.

- ↑ RGBl. I / 569 of July 5, 1934, preamble, quoted from HGB, text edition with references and index, C. H. Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Munich and Berlin 1952, p. 664.

Coordinates: 51 ° 27 ′ 22 ″ N , 7 ° 0 ′ 15 ″ E