General German workers' association

The General German Workers 'Association ( ADAV ) was the first mass party of the German workers' movement . It was founded on May 23, 1863 in Leipzig / Kingdom of Saxony . The main founder was Ferdinand Lassalle . After his death in 1864 there were disputes about his successor. This crisis was only overcome under the chairmanship of Johann Baptist von Schweitzer from 1867. The ADAV had been in competition with the Social Democratic Workers 'Party from 1869 until the two organizations united at the Gotha Fusion Party Congress at the end of May 1875 to form the Socialist Workers' Party of Germany , the immediate forerunner of the SPD .

Prehistory and foundation

Approaches to an independent workers 'movement had already existed before the bourgeois-dominated revolution of 1848/49 , for example in the form of the League of Communists and the General Workers' Brotherhood. Both fell victim to reactionary politics after the defeat of the revolution . The Communist League was smashed by the authorities in connection with the Cologne Communist Trial; the workers' fraternization could no longer work due to the prohibition of political associations by the German Confederation in 1854. It was not until the end of the reaction era in the German states that the labor movement also opened up new opportunities for development at the beginning of the 1860s. Initially, workers' education associations emerged, partly supported by liberal and democratic politicians, especially in Saxony and some parts of Prussia . The essential impulses for founding a workers' party came from their environment.

With the support of the German National Association , a group of around fifty workers visited the World Exhibition in London in 1862 and made contact with foreign workers and political emigrants, including Karl Marx . Back in Germany, during a meeting in Leipzig, it was decided to convene a general German workers' congress. August Bebel , Friedrich Wilhelm Fritzsche and Julius Vahlteich belonged to the preparatory committee from the environment of the Leipzig Trade Educational Association . When the founding of a party became more and more apparent, Bebel withdrew from the preparations, since at that time he was still relying on cooperation with the bourgeois democrats. There were similar considerations for a congress in Berlin , Hamburg and Nuremberg . Such a meeting of Berlin workers was announced for November 1862. This did not take place, however, and the further preparations were left to the Leipzigers.

| Ferdinand Lassalle |

|---|

|

Lassalle was an active participant in the revolution of 1848/49 in the Rhineland and as such a companion of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels . Like them, he did not come from the working class , but, as a lawyer, was part of the educated middle class . Nonetheless, he came into contact with the emerging labor movement at an early stage and turned to it entirely at the beginning of the 1860s. In April 1862, he began speaking in meetings. His lecture on the special connection between the present historical period and the idea of the working class was also published as a workers' program , but was immediately confiscated by the authorities. In another lecture on the constitution , Lassalle demanded the implementation of a general, equal and direct suffrage against the background of the dissolution of the Prussian parliament in the same year . Some time later Lassalle was convicted for the first time because of this writing. Nevertheless, the speeches found an echo in the circles of the workers' education associations that were just emerging and were decisive for the Leipzig representatives to turn to Lassalle. |

This initially turned to the German National Association. Hermann Schulze-Delitzsch replied that the time was not yet ripe to accept workers into the association. He later said that they should feel like "spiritual honorary members". The committee, represented by Julius Vahlteich, Friedrich Wilhelm Fritzsche and Otto Dammer , among others, wrote a letter to the journalist Ferdinand Lassalle on February 11, 1863, to find out his opinion on the labor movement and the means it should use .

Lassalle responded to the committee on March 1, 1863 with his open letter of reply . In it he demanded programmatically:

“The working class must constitute itself as an independent political party and make universal, equal and direct suffrage the fundamental watchword and banner of this party. The representation of the working class in the legislative bodies of Germany - this is the only thing that can satisfy its legitimate interests in political terms. "

He went on to explain that the social situation of workers is determined by the ' iron wage law ', according to which real wages are just as high in the long term as is necessary to feed the required number of workers. He expected help from productive associations with the support of the state. | Ref =

Within the Leipzig committee, there were arguments mainly with liberal politicians who had previously promoted the local workers' association. In a vote, however, 1,300 people present declared themselves in favor of Lassalle's statements against 2 votes. A new committee prepared the establishment of a corresponding association. At the end of March 1863, workers' meetings took place in Hamburg , Düsseldorf , Solingen , Cologne , Barmen and Elberfeld (today both in Wuppertal ), which followed the Leipzig resolutions. Numerous other workers' associations, under the influence of the bourgeois liberals and democrats, rejected Lassalle's program.

On May 23, 1863, the General German Workers' Association was founded in the Pantheon in Leipzig by Ferdinand Lassalle and representatives from Leipzig, Hamburg, Harburg , Cologne, Düsseldorf, Elberfeld, Barmen, Solingen, Frankfurt am Main , Mainz and Dresden . Besides Vahlteich and Fritzsche, the founding members also included Theodor Yorck and Bernhard Becker . Lassalle was elected President for an initial five years. This position was significantly stronger than in the social democratic parties of the following decades, since the president had extensive freedom of action in his decisions. The approval of the 23-member board was only necessary afterwards. Here Julius Vahlteich played a prominent role as secretary. The seat of the association was Leipzig. The annual general assembly, which was made up of elected delegates, provided a certain compensation for the power of the president. However, this aspect of intra-party democracy remained of no significance until 1871. Manipulation on the part of the presidents and the board of directors also contributed to this. Since the existing association laws precluded the formation of local groups, every member had to join the central association. According to its programmatic self-image, the aim of the association was to “represent the social interests of the German working class”.

The optimistic mood of the new party was also expressed in the federal song by Georg Herwegh , which was written in the founding year and which remained an integral part of the labor movement's repertoire even after the end of the ADAV.

Man of work, woke up!

And know your power!

All wheels stand still.

When your strong arm wants it.

Your crowd of urges pale,

When you, tired of your burden,

put the plow in the corner.

When you call: it is enough!

Break the double yoke in two!

Break the misery of slavery!

Break the slavery of need!

Bread is freedom, freedom is bread!

Development until Lassalle's death

In particular, Lassalle's thesis of the iron wage law had considerable consequences for the positioning of the ADAV within the political spectrum and for its policies. It says that self-help institutions or trade unions ultimately cannot fundamentally change the social situation because wages would always remain close to the subsistence level, while the profits flow to the entrepreneurs. In Lassalle's opinion, the only way out was that the workers should become entrepreneurs themselves by setting up productive cooperatives. However, this was unthinkable without state support. Since the approval of funds for government expenditure was a matter for parliaments, the implementation of universal and equal suffrage was the central prerequisite for fundamental social changes. This position explains the relative closeness of the ADAV to the state and its reservations about recognizing the union labor movement.

For Lassalle, the main opponent of the labor movement was the liberal bourgeoisie, which betrayed the democratic demands of 1848. The labor movement has to tie in with this democratic tradition. The opposition to liberalism also meant that Lassalle did not shy away from a certain closeness to Otto von Bismarck , who at that time as Prussian Prime Minister was an opponent of the liberals in the constitutional conflict . Lassalle counted on Bismarck's support in overcoming the three-class suffrage and on state support for the establishment of productive cooperatives . In fact, Lassalle and Bismarck met several times in order - albeit in vain - to explore the possibilities of working together.

There was great concern in the liberal camp about the workers' transition to the new party. Not least for this reason, with the participation of liberal and democratic politicians, in 1863 the associations that were close to them came together in the Association of German Workers' Associations (VDAV). However, the establishment of the ADAV initially had no great response, and most of the politically interested workers remained loyal to the workers 'and workers' education associations. In view of the poor membership development of the ADAV, Lassalle expressed disappointment after a few months of existence.

“Isn't it, this apathy of the masses is desperate! Such apathy with a movement that takes place purely for them, purely in their political interest, and with the mentally immense means of agitation that have already been used and that would have had huge results with a people like the French ?! When will the dull people finally shake off their lethargy? "

In September 1863, Lassalle spoke again publicly at various meetings and also commented on the establishment of the VDAV. In this context, bloody clashes broke out in Solingen between his supporters and those of the Progress Party . As a result, he was again sentenced to prison. Despite all efforts, the ADAV initially remained largely unsuccessful in Berlin. There it had 200 members at the end of 1863, but this number subsequently fell back to 35. Marx and Engels also faced headwinds: They suspected the idea of overcoming capitalism through productive cooperatives. They particularly criticized Lassalle's attitude towards liberalism, since they were of the opinion that the labor movement had to fight the reaction together with the bourgeoisie before the workers could then go on to their own revolution . Marx warned Wilhelm Liebknecht in a letter not to get involved politically with Lassalle, but also not to speak openly against him. Opposition also came from within. Julius Vahlteich resigned from his post as secretary in January 1864 in protest against Lassalle's dictatorial behavior.

Lassalle died on August 31, 1864 after a duel. At his death, the ADAV had around 4,600 members. In the same year, the federal song of the ADAV was replaced by a workers' marseilleise, with which board member Jacob Audorf set a musical memorial to the charismatic party founder on the occasion of his funeral ceremony. On the melody of the Marseillaise he composed the refrain, which was sung for a long time:

We do not count the enemy.

Not all the dangers:

We only follow the bold path,

who led us Lassalle!

Membership structure and regional distribution

Although the paid party apparatus was small - initially only the club secretary received a salary - the ADAV nevertheless had considerable costs. The local agitation had to be paid for, as well as brochures and the party organ, the Social Democrat, cost money, although this actually did not belong to the party, but to Schweitzer. Unlike the liberal parties, these expenses could not be covered by donations from wealthy patrons. In contrast to the bourgeois dignitaries parties, the party was a member party from the start. The contribution was 2 silver groschen. With an annual income of 200 thalers that was about 0.43% of the income. For many workers, especially in the homeworking areas, this was still too high. There the fees were then reduced. For this reason, too, the party's financial situation has always remained tense.

For the centralism of the organization, not only the association laws were decisive, but also, as in the case of the strong position of the president, the political conception of Lassalle, who dismissed the bourgeois, federal association culture as "club gimmick" and relied on a "dictatorship of insight". For him, this was a prerequisite for building a strong organization. The uniformity of the party was, as the party press wrote, “the greatest gem. (...) Following a lead, they [the workers] can really gradually become master of their powerful opponents, supported by all existing institutions; maintaining uniformity, keeping the division at bay, that is the main organizational task. "

Local “communities” emerged as grassroots organizations, but taken on their own, they should not have an independent policy. Although these had a board of directors, they were headed by an authorized representative of the entire association. In practice, however, these developed a life of their own. Those local groups that emerged from the workers' association movement continued their educational work and developed their own local association culture. This included setting up auxiliary funds, holding parties and excursions or even building libraries. The personality cult around Ferdinand Lassalle became central to the cohesion, especially after his death. Overall, the ADAV showed clear signs of a social democratic milieu, albeit with local differences. Women only played a subordinate role, not just because of the restrictive association laws. Corresponding tendencies, apart from the leadership role of Countess Hatzfeldt, met with rejection from the party's male supporters.

The reasons to join the ADAV varied greatly from region to region. The radically anti-bourgeois and anti-liberal program was particularly successful among small craftsmen and in areas with anti-capitalist and democratic traditions. These included Hamburg, Harburg, Frankfurt am Main and the surrounding area. There were more social revolutionary and radical democratic tendencies within the ADAV. In contrast, Lassalle's socio-economic ideas met with approval in older industrial regions such as Saxony and in areas with a home-business structure in crisis, for example in the Ore Mountains . Also important were areas in which, as in the Bergisches Land or in the Brandenburg Sauerland, the small producers had become heavily proletarianized and a strongly polarized society had long emerged as a result of the early industrial development . In this way, the ADAV was able to build on the traditions of 1848/49 in the Rhineland and in the Bergisches Land. In these older and sometimes crisis-threatened regions, the productive cooperatives, interpreted in a socialist way, met with approval.

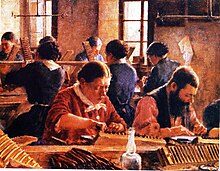

Due to the different economic structure, the members came from different strata of the emerging workforce. In the Westphalian region, it was not so much the mass workers of the new industries, such as iron production, that belonged to the ADAV, but there were many employees in industries that were still heavily crafted . In Solingen this included the knife manufacturers, in Iserlohn it was the workers in the metal goods industry. It was reported from Eschweiler that the factory workers but not the miners had joined the association. The proportion of craftsmen was also quite considerable. In Hamburg and probably elsewhere, membership was limited to traveling journeymen, while the ADAV found little support from the local journeymen and masters. The employees in the old and new home business also played a not insignificant role. In Silesia this included the weavers. In East Westphalia and parts of Saxony, the cigar workers belonged to a group that was important for the emergence of the organized labor movement. Unless the production took place in the proto-industrial home trade , the cigars were made in factories . The largely lack of machine noise made communication there easier. Despite their craft-like activity, the cigar makers lacked a corresponding social prestige. As with the founding of the workers ’brotherhood, the printers played an important role . They had a craftsmanship that went back to pre-industrial times and were relatively educated. However, their qualifications were increasingly devalued by mechanization in the printing trade, and the previous social security and almost class exclusivity were in danger. It was no coincidence that the ADAV was founded in the city of Leipzig, which was the center of publishing in Germany at that time. There, political communication was also promoted by its character as a trade fair and university city and as a traffic center.

While the older research had emphasized the importance of the craftsmen and the home traders, more recent studies come to the conclusion that in addition to these undoubtedly important groups, modern wage and factory workers were also relatively strongly represented among the members of the ADAV as early as the 1860s was.

The ADAV until the split

The internal development between 1864 and 1867 was determined by factional struggles for leadership in the ADAV. These were not so much substantive differences, but mainly purely personal quarrels. However, questions of management style played a role, as did the problem of whether the financially troubled club should be handed over to a patron in the person of Countess Hatzfeld .

The search for a new chairman was already difficult. Bernhard Becker, who was appointed by Lassalle in his will, encountered resistance from Sophie von Hatzfeldt, Lassalle's influential temporary partner. In addition, Becker had discredited himself by breaking the association's statutes. In the course of this dispute, the first split-offs occurred from Leipzig before Becker resigned.

The idea of making Karl Marx his successor was dashed by irreconcilable programmatic differences. As a result, there was a rapprochement when the inaugural address designed by Marx for the International Workers' Association also appeared several times in the new ADAV newspaper Der Social-Demokratie , published by Johann Baptist von Schweitzer . But the final break between Schweitzer on the one hand and Marx, Engels and Liebknecht on the other came in 1865 after the publication of articles that positively assessed Bismarck's policies . The attitude of the party paper towards the bourgeois parties and the personality cult around Lassalle also contributed to the distancing.

From November 30th to December 1st, 1865, the 2nd General Assembly of the ADAV took place in Frankfurt am Main. The approximately 5000 members were represented by nineteen delegates. Other sources speak of 9400 members from 67 locations. Carl Wilhelm Tölcke was unanimously elected President after the term of office had been shortened to one year. During this meeting, at the suggestion of Friedrich Wilhelm Fritzsche, the General German Cigar Workers Association was founded as the first centrally organized trade union.

In 1866, in the course of several people's assemblies in Dresden, the ADAV and the VDAV came together for the first time . August Bebel, as a representative of the workers' associations, spoke out in favor of a merging of both directions, for example on the question of electoral law. Within the ADAV, President Tölcke had to deal with a double opposition. These were the supporters of Countess Hatzfeldt, with a focus on Solingen, as well as the club newspaper behind Schweitzer and the Leipzig police, who refused to recognize Tölcke due to old prison sentences. Tölcke was unable to cope with this pressure and resigned. For this reason, an extraordinary general assembly of the ADAV took place on June 17th. At that time, the association had around 9400 members. Töclke's successor was August Perl after a fight vote . The participation of some Saxon members of the association in the founding of the Saxon People's Party met with criticism in large parts of the organization because of the People's Party's critical attitude towards Prussia. In fact, the contrast between the ADAV and the Saxon People's Party (and the later SDAP) was primarily determined by the different assessments of the national question. While the followers of Lassalle small German had set -preußisch stood Bebel and Liebknecht on the pan-German and anti-Prussian side.

At the fourth general assembly of the ADAV on December 27, 1866, there was a final break with Countess Hatzfeld, who then founded the Lassalleschen Allgemeine Deutsche Arbeitserverein (LADAV) ("Hatzfeldtians") as a spin-off in 1867 . In the majority organization, Perl was confirmed as chairman. This also gave itself a new program in which the party demanded the dissolution of every confederation of states , specifically the emerging North German Confederation , in favor of a unified state . Furthermore, the introduction of universal, equal and direct suffrage and diets for MPs were called for. The newly elected Reichstag of the North German Confederation should not only have an advisory, but a decision-making role. In addition, the establishment of free workers' associations to solve the social question was again called for.

In the elections for the constituent North German Reichstag, the Saxon People's Party and ADAV put up their own candidates. Due to the different regional focuses, however, there was hardly any direct competition, since both parties only ran for candidates in a few constituencies. While two representatives - Bebel and Reinhold Schraps from the People's Party - were also elected, the ADAV received nothing.

The Schweitzer era

At the time of the 5th General Assembly of the ADAV on 19./20. May 1867 there were sub-clubs in 45 places, which together only had about 2500 members. At this meeting Johann Baptist von Schweitzer was re-elected President with almost dictatorial powers. The latter declared that the working class should remain in "the sharpest opposition" to the reactionary powers that rule in Prussia and the North German Confederation.

In the elections for the first regular Reichstag of the North German Confederation, ADAV Schweitzer, Peter Adolf Reincke (for whom Fritzsche later took over the mandate) and, in a by-election, Wilhelm Hasenclever were elected. Friedrich Wilhelm Emil Försterling and Fritz Mende joined the LADAV . In the parliamentary negotiations, deep differences soon emerged again between Liebknecht, as the representative of the Saxon People's Party, and Schweitzer. Both were unanimous in their rejection of the internal structure of the North German Confederation. While the Greater German-minded Liebknecht completely rejected the covenant, Schweitzer was more willing to compromise. There were also major differences in the role of Parliament. For the Marxist Liebknecht, parliamentary work at this point in time beyond its contribution to agitation made no sense; rather, active cooperation would mean indirect recognition of the instruments of bourgeois class rule. Schweitzer, on the other hand, wanted to use parliament in the Lassallean sense to represent the interests of the workers, especially in the forthcoming economic legislation.

In parliament, Schweitzer made a name for himself as an advocate of a distinctly socialist position. He called for the unrestricted right of coalition , the ban on child and Sunday work , the state restriction of working hours (ten-hour day), a tightening of the state trade supervisory authority and the final ban on the truck system . A corresponding application failed in Parliament in the preliminary phase. Schweitzer did not succeed in gaining the necessary support for a contribution. Liebknecht, for example, refused to sign in order not to support the North German Confederation with what he believed was progressive legislation. In addition, a certain distance from Lassalle's ideas became clear in some parliamentary contributions by Schweitzer. In the creation of political freedom one no longer hoped for the state of Bismarck, rather the workers would have to fight for it themselves. Efforts at national level would not be enough. Only a fight in league with the workers of the other states would be successful. The demand for productive cooperatives, which was once so important, also lost its importance. The greater participation of workers in economic profits, for example through trade unions, became more important.

The ADAV's policy under Schweitzer, which went beyond Lassalle, initially led to a new internal unity. The organization became more attractive to the outside world and attracted new members. At the 7th General Assembly from 23 to 26 August 1868 in Hamburg, 36 delegates represented 83 locations. Depending on the source, the number of members varies between around 7,200 and 8,200. The most important issue was the strike and trade union issue . This became topical on the one hand through an extensive strike movement and on the other hand through the impending lifting of the coalition ban. In fact, building trade unions contradicted the principle of the “iron wage law”, according to which efforts to raise wages seemed doomed to failure. But Schweitzer was also pragmatic enough with a view to attracting new members to urge the party to take action in this regard. However, he was only able to overcome the resistance by threatening to resign. The assembly approved a motion that did not regard the strike as a suitable means of fundamentally changing the conditions of production and thus the position of the workers; nevertheless it is suitable to strengthen class consciousness, to break the patronage of the police and to eliminate individual grievances. It was decided that a general workers' congress should be convened to decide on the establishment of general unions.

The ADAV was dissolved by the Leipzig police authority on September 16, 1868, as it had founded branch associations despite the ban. The re-establishment took place on October 10, 1868 in Berlin.

The announced general workers' congress also took place in Berlin from September 26th to 29th, 1868. There were over 200 delegates from 110 locations, who together represented over 140,000 workers. It was decided to found a General German Workers' Union as a trade union umbrella organization. Its president also became Swiss. Marx immediately rejected the statutes of the organizations because they were based on the organizational principles of the ADAV. In response to the ADAV's initiative, Max Hirsch began to found the liberal Hirsch-Duncker trade associations and August Bebel also drafted a model statute for the VDAV's intended establishment of international trade unions . Probably also as a demarcation from the ADAV, the LADAV, which stated at its general assembly to organize almost 12,000 members, spoke out against strikes. Probably also because trade unions were incompatible with Lassalle's “iron wage law”, the decline of the party-affiliated trade union organization soon began. Just one year after it was founded, it dissolved in favor of a general German workers' support association. This initially had 35,000 members, but quickly lost its importance.

Reunion and internal conflicts

At the 9th general assembly of the ADAV from March 1, 1869 in Elberfeld (today in Wuppertal ) 67 delegates were present, representing 126 locations and around 12,000 members. The ADAV had thus gained around 5000 new members within a year.

Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel were also present as guests, who sharply attacked Schweitzer for his Prussian-friendly attitude. There were also clear reservations about the president within the organization itself. In the election of the board of directors, a majority of 42 delegates voted for Schweitzer, but at least 12 delegates, backed by 4,500 supporters, abstained. In response to the president's high-handed approach, his powers were severely restricted. Despite the open criticism, an agreement was reached some time later between Bebel, Liebknecht and Schweitzer not to attack each other and to support each other in the Reichstag.

In the Social Democrat of June 18, 1869, Schweitzer as ADAV President and Mende as President of the LADAV called for the reunification of both parties, which actually happened soon. A central reason for the willingness to rejoin the ADAV was the catastrophic situation of the LADAV. The club's leadership hoped that certain conditions would save Lassalle's legacy by taking this step. However, since the association was based on the statutes of 1863, it meant that the extensive powers of the president were back in force. The association was connected, among other things, with the fact that the former supporters of the LADAV enforce a declaration stating that the founding of the ADAV unions had proven to be a failure.

Parts of the ADAV protested sharply against this as a “coup d'état” against the Elberfeld resolutions and the condemnation of the unions. In this context, some leading members of the ADAV, especially Samuel Spier , Wilhelm Bracke and Theodor Yorck , called for a unification congress of the workers' movement. This call was associated with a sharp criticism of Schweitzer's policies, which were perceived as selfish. The critics left the ADAV. Most of the cigar and woodworkers followed the union leaders Fritzsche and York . Ultimately, the union with the LADAV did not pay off either, as the latter split off again in October 1869 due to disagreements about new rules of procedure.

Some time later, numerous representatives from various groups called for a unification congress. This took place from August 7th to 9th, 1869 in Eisenach . In addition to a number of former ADAV supporters and representatives of the VDAV, over 100 delegates from Schweitzer's supporters were also present. Since they did not want to join the newly founded SDAP , they were excluded from the assembly. The split-off and founding of a new competing organization led to a decline in the number of members of the ADAV. At the General Assembly of 1870 they dropped to about 8,000 and a year later there were only about 5200 paying members.

How differently ADAV and the Eisenachers faced the emerging small German empire was particularly evident at the outbreak of the Franco-German War . When the necessary war credits were approved, Bebel and Liebknecht abstained in the North German Reichstag and thus met with criticism from their own party. In contrast, Schweitzer and the former ADAV member Fritzsche clearly voted for it. However, both sides approached after the fall of Napoleon III. back to. Since the actual war goal had been achieved, both parties agreed to refuse a continuation of the fighting and the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine .

In the first elections to the Reichstag of the German Empire on March 3, 1871 , the ADAV received around 60,000 votes and the SDAP 40,000 votes. Of the representatives of the workers' parties, only Bebel and Schraps were able to maintain their seats. Schweitzer saw this as a clear election defeat and for this reason also declared his resignation. He stayed in office for a few more weeks, then withdrew completely from active politics and subsequently worked as a writer and playwright.

The time until the union of ADAV and SDAP

Wilhelm Hasenclever was elected as the new president in May 1871. The new party-owned newspaper, Der Neue Social-Demokratie, took the place of the Social Democrat , which had ceased to exist due to a decline in membership . In the following period the number of members increased again. At the General Assembly of 1872, 44 delegates represented around 7600 to 8200 members, depending on the source.

In the course of the meeting, the trade union movement was sharply criticized and an agreement with the SDAP was rejected. In contrast to the ADAV, the SDAP subsequently made active efforts to expand the unions. By the general assembly of 1873, the number of members had more than doubled to 16,000 to 19,000. The chairman Hasenclever was confirmed. Unification efforts were again rejected. Before the Reichstag election of 1874 , in which the party was able to win three seats, the two workers' parties stopped attacking each other, but the General Assembly of the ADAV of 1874 again spoke out against unification.

During parliamentary work, there were soon clear similarities between the two workers' parties on many issues. In addition, a personal relationship of trust gradually developed between the parliamentarians. Inadvertently, the state also reinforced the tendency towards unification through arrests and other measures taken by supporters of both parties. On June 8, 1874, the houses of leading politicians of the ADAV in Berlin were searched . A total of 87 ADAV supporters were arrested in the first half of 1874 and some of them, including Wilhelm Hasenclever, were sentenced to prison terms. In addition, the association in Berlin and some time later in most of the other Prussian cities was closed and dissolved on June 25th. The seat of the association has now been moved to Bremen. Not least because of the anti-social democratic measures taken by the Prussian authorities, the willingness to unite in the ADAV increased. Negotiations about this began in mid-October 1874. In January 1875, Hasenclever made it clear in an appeal to party members what conditions the ADAV imposed on an association. After that, their central demands would have to be reflected in a joint party program. He also spoke out in favor of maintaining tight management. On February 14th and 15th, members of both parties worked out the future program and organizational statute.

At a congress from 22 to 27 May 1875 in Gotha , the ADAV within the closed Gotha Program with the 1869 created SDAP the Socialist Workers Party of Germany together (SAPD), which in 1890 Social Democratic Party renamed (SPD).

On May 28, 1875, Wilhelm Hasenclever, the last president of the ADAV, who was now also a member of the board of SAP, announced the official dissolution of the ADAV.

ADAV (seat Hamburg)

An "orthodox-Lassallean" group led by CA Bräuer and J. Röthing split off from the ADAV in 1873 and was constituted in 1875 as the General German Workers' Association (Hamburg based) . The association, which probably had no more than a few hundred members, supported the Socialist Law and in 1909 joined the Reich Association against Social Democracy .

President

| Surname | Term of office | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| General German Workers' Association (ADAV) | ||

| Ferdinand Lassalle | May 23, 1863-31. August 1864 | |

| Otto Dammer | September 1st – 2nd November 1864 | Interim president |

| Bernhard Becker | November 2, 1864-21. November 1865 | |

| Friedrich Wilhelm Fritzsche | 21.-30. November 1865 | Vice President and Executive President |

| Hugo Hillmann | November 30th - December 31st December 1865 | Vice President and Executive President |

| Carl Wilhelm Tölcke | January 1, 1866-18. June 1866 | |

| August Perl | June 18, 1866–19. May 1867 | |

| Johann Baptist von Schweitzer | May 20, 1867-30. June 1871 | |

| Wilhelm Hasenclever | July 1, 1871-25. May 1875 | |

| Lassallescher General German Workers' Association (LADAV) (" Hatzfeldians ") | ||

| Friedrich Wilhelm Emil Foersterling | June 16, 1867–1868 | |

| Fritz Mende | July 5, 1868–1873 | |

Meetings of the ADAV

| date | place | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1863, May 23 | Founding meeting in Leipzig | |

| 1864, December 27-30 | 1st General Assembly in Düsseldorf | Julius Vahlteich is excluded from the party |

| 1865, November 30th to December 1st | 2nd General Assembly in Frankfurt / Main | Carl Wilhelm Tölcke is elected President |

| 1866, June 17th | 3rd General Assembly in Leipzig | Resolution: General Right to vote Main task of the ADAV; Perl becomes president |

| 1866, December 27th | 4th General Assembly in Erfurt | Break with Countess Hatzfeld |

| 1867, May 19-20 | 5th General Assembly in Braunschweig | Election of Johann Baptist von Schweitzer as President |

| 1867, November 22nd | 6th General Assembly in Berlin | Requirement: 10 hours a day |

| 1868, August 22nd to 26th | 7th General Assembly in Hamburg | Topic: strike and unions |

| 1869, March 28th to April 1st | 8th General Assembly in Elberfeld-Barmen | Limitation of the powers of the President |

| 1870, January 5th to 10th | 9th General Assembly in Berlin | |

| 1871, May 18-25 | 10th General Assembly in Berlin | Election of Wilhelm Hasenclever as President |

| 1872, May 22nd to 25th | 11th General Assembly in Berlin | Refusal to merge with SDAP |

| 1873, May 18-24 | 12th General Assembly in Berlin | Confirmation of Hassenclever in office |

| 1874, June 26th to 5th | 13th General Assembly in Hanover | Another vote against merger with SDAP |

The ADAV in historiography

Assessment of Marxist historiography

Although Marxism had prevailed in the Social Democrats, especially during the time of the Socialist Law , Ferdinand Lassalle remained extremely popular among the workers and supporters of the party. Not least because he and his successors represented opinions that did not agree with Marxism, the semi-official party historiography - for example by Franz Mehring - was critical of the founder and his party.

In view of Lassalle's continued popularity, Mehring argued that the “weaknesses” - for example, the open reply letter - existed primarily because Marx did not publish the decisive writings on many questions until after Lassalle's death. With regard to Schweitzer's policy, Mehring indicates a cautious move away from "the one-sidedness and weaknesses" of Lassalle. This probably meant a rapprochement with Marxist positions. However, for Mehring, the different positions on the German question and with regard to the assessment of parliamentarism remained dividing. Especially the statism of the ADAV judged Mehring critical. In the end, the position of the ADAV outlived itself. Behind this was the unspoken view that the Marxist position had since prevailed.

Despite all the criticism, Mehring ultimately gave a conciliatory verdict in an article in the Neue Zeit : “The German social democracy does not need to let this part of its party history, which is always very important, be ruined.” Above all because of its richness of detail, Mehring's history of German social democracy is important for the history of ADAV remains indispensable.

The criticism of Lassalle was radicalized in the 20th century by the history of communism, especially in the GDR . In the history of the German labor movement published by the Institute for Marxism-Leninism at the Central Committee of the SED , Lassalle was accused of having taken up some of Marx and Engels' ideas, but distorted them and spreading “a system of shameful opportunist ideas” in the German labor movement. Even if this work of party hagiography did everything to make the ADAV a marginal phenomenon, there was no avoiding admitting that the association was "an important link in the chain of associations that led to the emergence of the socialist labor movement", has been. Quoting Lenin , the SED saw the historical merit of the ADAV in the fact that it “turned the working class out of an appendage of the liberal bourgeoisie into an independent political party.” Nevertheless, the ADAV as a whole was - based on Karl Marx's comments in his criticism of the Gotha program - as a sectarian state socialist and class-conciliatory wrong way, and the own line of tradition (the SED) traced back to the direction around August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht.

With regard to concrete research, there has been a clear objectification and preoccupation with the topic in the GDR, especially since the 1980s. In the last years of the existence of the GDR and the turning point around 1989/90, three dissertations on ADAV were written in Leipzig, which admittedly adhered to some of the traditional basic assessments of the SED, but in some cases significantly modified them.

Research in the Federal Republic

In the Federal Republic of Germany, too, current political phenomena have shaped the attitude towards the ADAV and Lassalle. After the fall of Godesberg , the SPD used the state-affirming and social reform aspects to historically legitimize its changed position.

The development in national and later all-German research is contradicting itself. The history of the ADAV is easily accessible through Dieter Dowe's collection of key party materials and documents . However, there are gaps in the tradition of the club magazines. There are also bibliographies on the topic. In the more recent academic research in the Federal Republic of Germany, however, there are only a few monographic works that completely trace the history of the party. More recently, there is a volume published by Toni Offermann with materials on organization and social structure. The work of Arno Herzig 1979 tried a biographical approach, the development of the party to trace. This work beyond Tölcke is of great importance for the history of the party as a whole. There are also a number of local or special studies. There are also articles in anthologies and the relevant scientific journals.

The ADAV plays an important role in the presentations on the early history of the labor movement. The works of Thomas Welskopp and Christian Gotthardt from the last few decades should be mentioned above all. Both of them are primarily concerned with the emergence of local (social democratic) milieus and not so much with the organization and development of the party itself. In some overall presentations of the history of social democracy, as with Heinrich Potthoff, the history of the ADAV is essentially limited to the activities of Lassalle the much longer phase after that remains hidden. Likewise, Helga Grebing's portrayal is centered on people and ideology . If Grebing had emphasized the ideological differences between the two competing workers' parties, Potthoff argues that the similarities outweighed the majority and that the ADAV was closer to Marxism than has often been claimed. Lassalle's agitation dominates even in modern overall presentations of the history of social democracy, for example by Lehnert, while the Schweitzer era hardly plays a role. Lehnert also sees more similarities than what separates ADAV and the Eisenachers. Above all, however, he emphasizes that the importance of the ADAV lay in the separation of the labor movement from the liberal bourgeoisie.

Thomas Nipperdey emphasizes the differences between the ADAV's program and Marxism from the large overall accounts of German history that have appeared in recent decades . He too emphasizes the break with liberalism. It was something new that, based on Lassalle, a political belief emerged with which the members identified, created meaning and shaped all of life. Even Hans-Ulrich Wehler emphasizes the separation of liberalism as a result of the occurrence of the ADAV. He also emphasizes the anti-union stance and the dictatorial style of leadership within the new party. For both authors, the contrast between ADAV and the Eisenachers on the German question plays an important role.

literature

- Heinrich Laufenberg : History of the labor movement in Hamburg Altona and the surrounding area. First volume. Hamburger Buchdruckerei and Verlagsanstalt Auer & Co, Hamburg 1911, pp. 195–434

- Bert Andréas : Ferdinand Lassalle - General German Workers' Association: Bibliography of their writings and the literature on them from 1840 to 1975 . Bonn 1981, ISBN 3-87831-336-5

- Karl Ditt : The political labor movement in western Westphalia from its beginnings to the socialist law . In: Bernd Faulenbach , Günther Högl: A party in their region. On the history of the SPD in western Westphalia . Essen 1988, pp. 64-70.

- Dieter Dowe : Germany: The Rhineland and Württemberg in comparison . In: Jürgen Kocka (ed.): European workers movements in the 19th century. Germany, Austria, England and France in comparison . Göttingen 1983, ISBN 3-525-33488-5 , pp. 77-105

- Bernt Engelmann : Forward and don't forget. From the persecuted secret society to the Chancellor's party. Ways and wrong ways of the German social democracy . Munich 1984, ISBN 3-442-08953-0

- Helga Grebing : History of the German labor movement . Munich 1966.

- History of the German labor movement. Timeline. Part 1. From the beginning to 1917 . Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1965, pp. 57-106

- Arno Herzig: The General German Workers' Association in German Social Democracy - depicted on the biography of the functionary Carl Wilhelm Tölcke (1817-1893) . Berlin: Colloquium Verlag, 1979 (supplements to IWK, vol. 5), 417 pp.

- Detlef Lehnert: Social Democracy. Between protest movement and ruling party 1848-1983 . Frankfurt 1983, ISBN 3-518-11248-1

- Franz Mehring : History of the German Social Democracy. Second part. From Lassalle's 'open reply' to the Erfurt program from 1863 to 1891 . Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1960, pp. 1–370 ( Thomas Höhle , Hans Koch , Josef Schleifstein (Eds.): Franz Mehring. Collected writings . Volume 2.) First edition 1897–1898 here after the 2nd verb. u. probably printed 1903–1904 edition.

- Toni Offermann: The first German workers' party. Organization, distribution and social structure of ADAV and LADAV 1863–1871 . ISBN 3-8012-4122-X (book edition + CD-ROM)

- Toni Offermann: The regional expansion of the early German labor movement 1848 / 49-1860 / 64 . In: Geschichte und Gesellschaft Heft , 4/1987. Pp. 419-447.

- Franz Osterroth / Dieter Schuster: Chronicle of the German Social Democracy. Vol. 1: Until the end of the First World War . Bonn / Berlin 1975.

- Wilhelm Heinz Schröder : Workers 'History and Workers' Movement. Industrial work and organizational behavior in the 19th and early 20th centuries . Frankfurt 1978

- Klaus Tenfelde : The emergence of the German trade union movement. From the pre-march to the end of the socialist law . In: Ulrich Borsdorf (Hrsg.): History of the German trade unions from the beginning to 1945 . Cologne 1987, ISBN 3-7663-0861-0

- Walter Tormin : History of the German parties since 1848 . Stuttgart 1967.

- Hartmut Zwahr : The German Labor Movement in Country and Territory Comparison 1875 . In: Geschichte und Gesellschaft , No. 4 1987. pp. 448–507

- Hartmut Zwahr: On the constitution of the proletariat as a class. Structural study of the Leipzig proletariat during the industrial revolution . Munich 1981, ISBN 3-406-08410-9 ,

- Wolfgang Schröder: Leipzig - the cradle of the German labor movement. Roots and development of the workers' education association 1848/49 to 1878/81 . Karl Dietz Verlag, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-320-02214-3

Web links

- Representation of the ADAV. German Historical Museum

- ADAV / Lassalle archives in the IISG

- Ferdinand Lassalle: Open reply (PDF; 2.42 MB)

Remarks

- ↑ Chronicle, p. 21 f.

- ↑ Grebing, p. 62.

- ^ Chronicle, pp. 21-23

- ↑ Chronicle, pp. 22–24. Offermann: Labor Party . P. 72

- ↑ cit. after Grebing, p. 63.

- ^ Tormin: History of the German parties . P. 66

- ↑ a b Chronicle, p. 25f.

- ^ Grebing, p. 63.

- ↑ Recording according to the Edison method (approx. 1909) (MP3; 2.2 MB)

- ^ Offermann: Workers' Party . P. 63f.

- ^ Social Democrat of February 6, 1870. quoted in. According to Offermann: Workers' Party . P. 50.

- ^ Offermann: Workers' Party . Pp. 51-57.

- ↑ Dieter Dowe: Germany: The Rhineland and Württemberg in comparison . In: Jürgen Kocka (ed.): European workers movements in the 19th century. Germany, Austria, England and France in comparison . Göttingen 1983, ISBN 3-525-33488-5 , pp. 77-105. Toni Offermann: The regional expansion of the early German labor movement 1848 / 49-1860 / 64 . In: Geschichte und Gesellschaft , issue 4/1987, pp. 419–447. Toni Offermann: Workers' Party . P. 58f.

- ↑ Grebing, p.67. Hartmut Zwar: The German Labor Movement in Country and Territory Comparison 1875 . In: Geschichte und Gesellschaft , No. 4, 1987, pp. 448–507. Hartmut Zwar: On the constitution of the proletariat as a class. Structural study of the Leipzig proletariat during the industrial revolution , Beck, Munich 1981, ISBN 3-406-08410-9 , p. 320. The example of Westphalia: Karl Ditt: The political workers' movement in western Westphalia from the beginnings to the socialist law . In: Bernd Faulenbach, Günther Högl: A party in their region. On the history of the SPD in western Westphalia . Essen 1988. pp. 64-70. To the tobacco workers: Wilhelm Heinz Schröder: Workers 'history and workers' movement. Industrial work and organizational behavior in the 19th and early 20th centuries . Frankfurt 1978, v. a. Pp. 120–149, pp. 237–253., Offermann: Arbeiterpartei . Pp. 222-230.

- ^ Offermann: Workers' Party . P. 133.

- ^ Offermann: Workers' Party . P. 137.

- ↑ All official information from the ADAV itself on the number of members is extremely uncertain. Recent research has shown some completely different figures. Offermann: Labor Party . P. 111.

- ↑ a b c d e Offermann: Workers' Party . P. 111.

- ↑ Chronicle, pp. 26–31.

- ↑ Chronicle, p. 31 f. Offermann: Labor Party . P. 111.

- ↑ cf. from the perspective of a contemporary Marxist-oriented social democrat: Franz Mehring : German history from the end of the Middle Ages . (First time in Berlin, 1910/11) Reprinted here: Düsseldorf 1946. p.190, on the trade union question in detail: Klaus Tenfelde: The emergence of the German trade union movement. From the pre-march to the end of the socialist law . In: Ulrich Borsdorf (Hrsg.): History of the German trade unions from the beginning to 1945 . Cologne 1987, ISBN 3-7663-0861-0 , p. 100.122.

- ↑ Engelmann, p. 117. Chronicle, p. 32

- ^ Franz Mehring: German history . P. 191 f.

- ↑ Chronicle, p. 33. Engelmann, p. 118.

- ↑ Chronik, p. 34, p. 36. Engelmann, p. 122f.

- ↑ Chronicle, pp. 35–37. Engelmann, p. 126. Offermann: Workers' Party . Pp. 200-207.

- ↑ Chronicle, p. 37f. Engelmann, p. 127

- ^ Offermann: Workers' Party . P. 111

- ^ Grebing, p. 89

- ↑ Chronicle, p. 41 f.

- ↑ Chronicle, pp. 42–47

- ↑ Chronicle, pp. 47–50. Engelmann, p. 151.

- ↑ Dieter Fricke: The German labor movement 1869-1890. Your organization and activity . Leipzig 1964, p. 92f

- ^ R. Grau, E. Illgen, L. Kaulisch: Appendix . In: Institute for Marxism-Leninism at the Central Committee of the SED , History of the German Labor Movement , Biographical Lexicon, p. 507, Dietz Verlag , Berlin 1970.

- ^ Franz Mehring: German history from the end of the Middle Ages . Berlin 1910/11, pp. 176-180, 187-192

- ↑ Quoted from Offermann: Workers' Party . P. 40.

- ^ Franz Mehring: History of the German Social Democracy . Berlin 1897/98 [of which there are numerous reprints and reprints, some with different subdivisions in individual volumes].

- ↑ History of the German labor movement . Volume 1: From the beginnings of the German labor movement to the end of the 19th century . Institute for Marxism-Leninism at the Central Committee of the SED, Berlin 1966, p. 211.

- ^ Offermann: Workers' Party . P. 45.

- ^ Peter Polenz: Development and Differentiation in the General German Workers' Association 1863 to 1867 . Leipzig 1986. Christine Lasch: Development and differentiation in the general German workers' association 1868 to 1870 . Leipzig 1990. Otto Warnecke: Development and Differentiation in the General German Workers' Association 1871–1873 , 1992. (cf. Offermann: Arbeiterpartei . P. 36)

- ^ Offermann: Workers' Party . P. 46.

- ↑ Dieter Dowe (Ed.): General German Workers 'Association: Protocols and materials of the General German Workers' Association (including splinter groups) . Berlin 1980. Offermann: Workers' Party . P. 38

- ^ Bert Andréas: Ferdinand Lassalle - General German Workers' Association: Bibliography of their writings and the literature about them 1840 to 1975 . Bonn 1981, ISBN 3-87831-336-5 , holdings of the ADAV library (as of 2005) (PDF; 34 kB) Friedrich Ebert Foundation

- ↑ This statement is based on research in the KVK with the search terms ADAV and General German Workers' Association. Offermann confirms this assessment: Workers' Party . P. 40.

- ^ Toni Offermann (ed.): The first German workers' party: materials on the organization, distribution and social structure of ADAV and LADAV 1863–1871 . Dietz, Bonn 2002, ISBN 3-8012-4122-X

- ^ Arno Herzig: The General German Workers' Association in German Social Democracy; Depicted in the biography of the functionary Carl Wilhelm Tölcke . Berlin 1979

- ↑ As an example: Heinz Hümmler: Opposition to Lassalle: The revolutionary opposition in the General German Workers' Association 1862 / 63–1866 . Berlin 1963 ,. Christiane Eisenberg: Early Labor Movement and Cooperatives: Theory and Practice of Productive Cooperatives in German Social Democracy and the Trade Unions of the 1860s / 1870s . Bonn 1985. Shlomo Na'aman : The constitution of the German labor movement 1862/63: Presentation u. Documentation . Assen 1975

- ↑ about in: Arno Herzig (Hrsg.): Origin and change of the German workers' movement . Hamburg 1989

- ↑ Thomas Welskopp: The banner of brotherhood. The German Social Democracy from Vormärz to the Socialist Law . Berlin 2000. Christian Gotthardt: Industrialization, bourgeois politics and proletarian autonomy. Requirements and variants of socialist class organization in north-west Germany, 1863 to 1875 . Berlin 1992 (cf. Offermann: Arbeiterpartei . P. 35.)

- ^ Heinrich Potthoff: The social democracy from the beginning to 1945 . Bonn 1974. pp. 25-29

- ↑ Grebing: History of the German labor movement . Pp. 61-68.

- ↑ Lehnert: Social Democracy . P. 52 f.

- ↑ Thomas Nipperdey : German History 1866-1918 . Vol II: Power state before democracy . Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-44038-X SS744

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : German history of society . Volume 3, Munich 1995, p. 157 ff., P. 348