History of the German Social Democracy

bottom row: Carl Wilhelm Tölcke , Ferdinand Lassalle for the ADAV)

The history of German social democracy goes back to the first half of the 19th century. During this time, early socialist- oriented exile organizations emerged - especially in France, England and Switzerland; and in the wake of the bourgeois March Revolution in 1848 with the General German Workers 'Brotherhood , the first supra-regional organization of the workers' movement in the states of the former German Confederation , which initiated the development of both the trade unions and the socialist parties in the German-speaking area.

After the end of the reaction era that followed the revolution of 1848/49 , social democratic parties began to form in the 1860s, establishing the tradition of the current SPD . On May 23, 1863, the General German Workers' Association (ADAV) was founded in Leipzig , initially headed by Ferdinand Lassalle . In addition, the Eisenach direction emerged from the middle / end of the 1860s , mainly shaped by August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht (1866 Saxon People's Party , 1869 Social Democratic Workers' Party SDAP). Both directions had conflicts with regard to the trade union question and the form of the emerging German nation-state, but merged in 1875, four years after the establishment of the German Empire in 1871 , to form the Socialist Workers' Party (SAP).

The "Law against the Public Dangerous Endeavors of Social Democracy" ( Socialist Law ), initiated by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck in 1878, amounted to a party ban, as a result of which the workers' movement was massively hindered until the end of the 1880s. After the law was repealed, the SAP was renamed the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) in 1890 . Under this name it developed into a mass party in terms of membership numbers and election results in the following years . After the Reichstag election in 1912 , the SPD formed the strongest parliamentary group in the Reichstag for the first time, ahead of the Center Party . However, it remained in the opposition until the October reform of 1918 - almost until the end of the First World War - since in the German Empire the government appointed by the monarch (from 1888 Wilhelm II. ) Did not need a majority in parliament because it only required the German Kaiser was responsible to.

Over the years there have been various currents and wings in social democracy, which have also led to secession. With the exception of the Communist Party (KPD), all the parties that had split off dissolved after a while, joined the KPD or returned to the SPD.

At the beginning of the party's history, radical democratic currents dominated under the influence of the ideas of Ferdinand Lassalle. Its cooperative orientation, which was later subordinated to a more union-oriented orientation, had a particular effect . In the longer term, Marxism prevailed. The transformation started by the end of the 1890s with the inner-Party revisionism debate in which at reforms were oriented implementation attempts of Marxist content meaning. After the death of August Bebel in 1913, the revolutionary wing of the party, which dominated the first decades, fell into a minority position.

Marx's analysis of the social and economic social conditions as well as their historical development, and the revolutionary concepts of action derived from it, shaped social democracy ideologically into the second half of the 20th century.

During the First World War , the opponents of the war-approving truce policy around Hugo Haase and Georg Ledebour formed the Social Democratic Working Group (SAG) in the SPD parliamentary group from the end of 1915 . Three months later, in March 1916, they were excluded from the SPD and in 1917 they founded the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD). After this split off, the remaining SPD operated under the name of the Majority Social Democratic Party of Germany (MSPD) for the next four to five years . From the left-wing revolutionary wing of the USPD, the Spartakusbund , after the November Revolution , on the initiative of Karl Liebknecht , Rosa Luxemburg a . a. in January 1919 the KPD emerged, which the left majority of the USPD also joined in 1920 (see VKPD ). Most of the remaining USPD turned back to the SPD in 1922. The USPD existed as a small splinter party until 1931.

During the Weimar Republic , the SPD was one of the parties that supported the new form of government of a pluralistic democracy. Between 1919 and 1925, Friedrich Ebert was the first democratically elected Reich President. In the first two years of the republic and then again from 1928 to 1930, it was the leading ruling party in the Reich in alternating coalitions with Reich Chancellors Friedrich Ebert, Philipp Scheidemann , Gustav Bauer and Hermann Müller . Between 1921 and 1923 she was involved in other constellations with cabinet members (ministers) in four other Reich governments. In the final phase of the republic the party was largely on the defensive; not least because it has not been able to develop a viable concept for the presidential cabinets since Heinrich Brüning and was also divided within the party in dealing with the political extremes that had increased. During this phase she was also increasingly attacked by the KPD, which she described as " social-fascist " and "traitors of the working class". In 1931, with the founding of the Socialist Workers' Party, there was another split on the left. As the global economic crisis wore on , the SPD had no majority-capable concepts to oppose the radical left and right wing parties and their populist- oriented promises of solutions.

After the beginning of the National Socialist dictatorship , the SPD was the only party in the Reichstag that rejected the Enabling Act after the KPD had already been banned by the Reichstag Fire Ordinance. As a result, the SPD was banned and the unions were smashed. Numerous members went into exile; others who had remained in the country saw themselves largely exposed to persecution, were temporarily imprisoned or held for years in concentration camps, where not a few Social Democrats were also murdered.

Leading social democrats who fled abroad formed the SOPADE in Prague in 1933, the most important exile organization of the SPD until the Second World War , mainly due to the publication of their reports on Germany . As a result of the “ smashing of the rest of the Czech Republic ”, it moved first to Paris in 1939 and then to Lisbon in 1940, where it effectively dissolved. As the successor to SOPADE, the German Labor Delegation in the USA and the Union of German Socialist Organizations in Great Britain established themselves as important exile organizations of German social democracy during the Nazi dictatorship.

Immediately after the end of World War II, the SPD was reorganized ideologically and organizationally largely based on the model of the Weimar period in the four zones of occupation . While there was a reorganization in the office of the Western Zones under Kurt Schumacher , in 1946 in the Soviet-occupied zone the union of the SPD and the KPD in the newly founded SED was carried out under partly repressive pressure from the CPSU leadership and influential KPD functionaries . The Stalinization of the following years removed the remnants of social democratic organizations and politics, which in the subsequent GDR became almost insignificant. In the western zones - from 1949 the Federal Republic of Germany - the SPD under the leadership of Kurt Schumacher strictly refused to merge with the KPD.

Domestically, the SPD , which was considered to be “ progressive ” or tended to be “ left ”, was the most influential opposition faction in the Bundestag from 1949 to 1966, behind the more “ conservative ” or moderately “ right ” party alliance of the CDU and CSU as the second strongest party political force , the highest federal republican parliament.

With the Godesberg program of 1959, the SPD largely turned away from Marxism. It no longer defined itself as a class party, but as a people 's party . This change, which implied a turning point in terms of content , initially made it possible in 1966 to join the CDU-led first grand coalition under Federal Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger , and from 1969 the first social-liberal coalition in post-war German history to be agreed at the federal level - now under the SPD leadership - with Willy Brandt as head of government. In the period that followed, his Ostpolitik in particular , but in some cases also in his own party, initiated internally controversial measures such as the radical decree with lasting political changes. Under Helmut Schmidt , Brandt's successor in the Chancellery, the political scope became narrower. The party came under increasing pressure due to domestic and foreign political crises. In view of the left-wing terrorism of the RAF (cf. Deutscher Herbst ), the conservative side called for a more rigorous approach to internal security. From the left wing of the party - reinforced by the New Social Movements that emerged in the wake of the student movement at the end of the 1960s - the energy policy and, above all, the approval of NATO's double decision were heavily criticized. After the break of the social-liberal coalition in 1982, a period of opposition marked by internal party crises began.

After German reunification in 1989/90 , the SPD's hopes of building on old electoral successes in the new federal states during the Weimar Republic were not fulfilled for the time being. There, the PDS, which emerged from the former GDR state party SED, was able to assert itself as a significant competing force against the SPD - albeit weakened - despite strong slumps shortly after the fall of the Wall , after the PDS distanced itself from the line of the SED and its former leadership excluded from the renewed party.

In 1998, after 16 years, the SPD's second opposition period in the history of the Federal Republic ended with the start of a red-green coalition under Gerhard Schröder as Federal Chancellor. Schröder's turn towards a more economically liberal policy in association with the British Labor government under Tony Blair (see: Schröder-Blair paper ), especially the Agenda 2010 , met with less and less approval from voters and his own supporters - a tendency that in January 2005 led to the split-off of part of the union-related left wing in the WASG . The new elections initiated by the government itself again resulted in a grand coalition of CDU / CSU and SPD in autumn 2005 . In the 2009 Bundestag election it became clear that the trend of voter emigration had continued. With 23% - a landslide loss of 11 percentage points compared to the election four years earlier - the SPD received its worst result at federal level since the Federal Republic was founded and had to switch back to the opposition bank after 11 years in government or government participation. A significant part of their former voters had migrated to the stronger party Die Linke (which was newly constituted in 2007 as a result of the merger of the WASG with the PDS) or to the camp of non-voters .

Emergence of the social democratic parties

First approaches in the pre-March period and the revolution of 1848/49

(Painting by J. Marx from 1889)

The social democratic movement in Germany has roots that go back to the Vormärz and the revolution of 1848/49 . Ideologically, the early French socialism of Charles Fourier , Auguste Blanqui or Henri de Saint-Simon initially played an important role. In addition, there were ideas from the emerging radical democratic currents of the pre-March opposition.

The first organizational approaches were the foreign associations of German craftsmen and political emigrants. These include the German People's Association, founded in Paris in 1832, renamed the Union of Outlaws in 1834 , and the secret society of Young Germany, founded in Bern in the same year . Influenced by Wilhelm Weitling , the Union of the Just split off from the Union of Outlaws in 1836 , although its focus shifted more and more to London in the 1840s. Under the influence of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels , he renamed himself the League of Communists . Marx and Engels wrote the Communist Manifesto for him in 1848 . During the revolution, the alliance was temporarily dissolved, and after it was re-established, ideological conflicts and divisions arose. After the Cologne communist trial, it ceased to exist. In Germany itself, during the revolution, Stephan Born , the General German Workers' Brotherhood, formed the first nationwide organization that already had many of the characteristics of a modern party and was also active in trade unions . After the revolution, the workers' brotherhood fell victim to the reaction policy in the German Confederation .

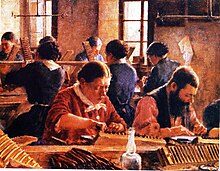

Social base

The organized political labor movement since the 1860s often followed the traditions of 1848/49 in terms of personnel. It was predominantly urban. Its core were not unskilled factory workers, but skilled craftsmen, workers with craft training and increasingly skilled workers. Sectors such as tobacco workers or book printers, in which manual work processes played a considerable role, were important. On the other hand, unskilled workers in new mass professions such as mining or the iron and steel industry were relatively weakly represented. Last but not least, the connection between the workers and parts of the urban anti-feudal and radical-democratic intellectuals was of great importance. From the beginning, social democracy was also a movement that was predominantly successful in Protestant regions. In Catholic Germany, the Kulturkampf in particular created a milieu that also included workers .

General German workers' association since 1863

A restart of political life, not only in Prussia, began in 1858 with the so-called New Era , i.e. H. the liberal turn in Prussian domestic politics, possible. Crafts and workers' training associations emerged, often supported by liberal or democratic-minded citizens. It soon became clear that some of the members also wanted to represent social and political interests. When it became clear that this was not possible within the framework of the liberal German National Association , a Central Committee established in Leipzig approached the author Ferdinand Lassalle in 1863 to appoint a general German workers' congress . Under his decisive leadership, the General German Workers 'Association (ADAV) was established on May 23, 1863 as the first German workers' party. The club managed to win a significant number of supporters in some areas, but contrary to Lassalle's expectations, it did not develop into a mass movement. After the early death of the founder, the organization split. Only under the leadership of Johann Baptist von Schweitzer did a consolidation come about from 1867.

The direction of Eisenach

After the founding of the ADAV, the Association of German Workers 'Associations (VDAV) was founded under the main leadership of the National Association to bind workers' associations to the civic camp . However, it did not succeed in preventing some of the members from becoming politicized. In addition, with the establishment of trade union organizations, economic advocacy began to gain in importance. Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel gained influence during the association day . Under the chairmanship of Bebel, the General Assembly of the Association decided in 1868 to join the International Workers' Association (in short: Internationale , in later historiography also referred to as the First International ). The still liberal-minded clubs then split off. The Saxon People's Party was founded in 1866, also with significant participation by Bebel and Liebknecht . This originally aimed at an alliance of bourgeois democrats and workers. After the success of the bourgeoisie largely failed to materialize, the workers increasingly dominated there too. On August 8, 1869, the Association of German Workers 'Associations, the Saxon People's Party and groups split off from the ADAV merged in Eisenach to form the Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP).

The programmatic basis of the new party was the Eisenach program . This program took over the statutes of the International Workers' Association with only a few minor changes. In addition, it also took up concepts from the Lassallean followers. The question of voting rights was brought to the fore and the demand for workers' associations was adopted. The party's aim was to establish a free people's state. In order to abolish class rule, it relied on overcoming the mode of production based on the wage system through cooperative work. She also supported the internationalist standpoint of the International Workers' Association.

From competition to association

ADAV and SDAP fought each other in the following years and differed opinions on the German question , for example . While the ADAV was oriented towards small German , the SDAP stood on the side of the greater German . There were also ideological differences. The iron wage law , which goes back to Lassalle, led to a pronounced statism and an attitude critical of the union at the ADAV . On the other hand, the SDAP was positive about the union idea, but refused to cooperate with the existing state. The contrasts lost their significance after the establishment of the Empire in 1871. At the same time, the anti-social democratic measures of the state in the Tessendorf era brought both parties closer together. This finally led to the merger to form the Socialist Workers' Party of Germany (SAP) at the unification party conference, which took place in Gotha from May 22nd to 27th, 1875 .

The Socialist Workers' Party of Germany from 1875

Program

The Gothaer program negotiated before the unification includes program components from both predecessor organizations. The phrase "transforming work equipment into the common good of society" came from representatives of the SDAP, while the demand for the establishment of socialist productive cooperatives was based on Lassalle's ideas. The majority of the short-term goals came from the Eisenach program. In contrast, the disqualification of the opponents as a reactionary mass and the demand for the breaking of the iron wage law were again ideas of the ADAV. The commitment to strive for a free state and a socialist society with all legal means was also due to the threatened and in some cases already implemented state repression measures.

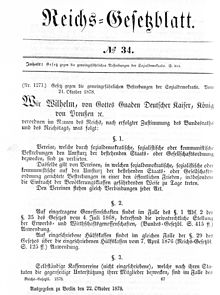

Social democracy under the Socialist Law 1878–1890

Ever since Bebel and Liebknecht openly committed to the revolutionary Commune , which had been proclaimed in Paris during the Franco-German War of 1870/71, the Social Democrats were considered enemies of the state. Its leading representatives, but also ordinary members, were exposed to various forms of persecution. Bebel and Liebknecht, for example, were sentenced to two years imprisonment each in a high treason trial in 1872. However, these measures did not weaken the social democratic movement. In the Reichstag elections of 1877 the united party got over 9% of the vote. Two assassinations carried out by individual perpetrators on Kaiser Wilhelm I in May and June of 1878 gave Bismarck the occasion for a now more aggressive anti-social democratic policy. The pro-government press did everything to bring the assassins closer to the Social Democrats. After the first attempt to introduce an exceptional law failed due to the resistance of the majority in the Reichstag, the second assassination attempt, in which the monarch was seriously injured, and the subsequent dissolution of parliament to the readiness of most of the national liberals, the To agree to socialist law.

The law made it possible to prohibit associations, meetings, pamphlets and money collections. Violations could result in fines or imprisonment. Residence bans could also be issued or a minor state of siege imposed on certain areas . However, the law was limited in time and therefore had to be repeatedly confirmed by parliament. The first confirmation followed in 1881. The law was subsequently extended several times.

The Socialist Workers' Party was effectively forced into illegality for twelve years. In addition to other social democratic publications, the official party organ, the Vorwärts , was banned as well as public appearances or meetings of the party. The law was not only directed against the SAPD itself, other workers' organizations such as the trade unions were also dissolved. Only the members of the state parliaments and the Reichstag faction of the SAPD retained their mandates or could continue to run for elections as individual candidates in the constituencies. Many party members were forced to emigrate or were expelled from their places of residence. However, in the course of the anti-social-democratic repression measures, the party was forced to gradually get rid of its left, social-revolutionary and tending to anarchist wing. In 1880, its most important representatives - Johann Most and Wilhelm Hasselmann - who had temporarily also belonged to the Reichstag faction of the SAPD (Most from 1874 to 1877, Hasselmann until 1880), were excluded from the party.

Since party conferences were no longer possible in Germany, secret SAPD conferences took place in neighboring countries. This happened around August 1880 at Wyden Castle in the canton of Zurich . There the party decided to delete the word “legal” from the party program, as this was now pointless. The party is now striving by all means to achieve its goals. A similar congress was held in Copenhagen in 1883 . A spectacular climax of the anti-social democratic measures was the secret society trial that took place between July 26th and August 4th 1886 before the district court of Freiberg in Saxony . Leading party members were charged, accused by the prosecution of being involved in a secret association. She viewed the Wyden and Copenhagen Congresses as such. Ignaz Auer , August Bebel, Karl Frohme , Karl Ulrich , Louis Viereck and Georg von Vollmar were each nine months; a number of other defendants were sentenced to six months in prison each. This process will be followed by several other legal proceedings against participants in the two congresses. In Frankfurt alone, 35 defendants were sentenced to up to one year in prison. In Magdeburg there were 51 convicts in 1887.

Limits of the Law

seated, seen from the left: Georg Schumacher , Friedrich Harm , August Bebel , Heinrich Meister and Karl Frohme . Standing: Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Dietz , August Kühn , Wilhelm Liebknecht , Karl Grillenberger , and Paul Singer

With the exception legislation, the state ultimately did not succeed in permanently weakening the social democratic movement. Rather, the party members kept in contact with one another on an informal level and in cover clubs. The funerals of prominent party members regularly became the occasion for mass gatherings, which made the continued existence of the movement clear to the outside world. In 1879, 30,000 workers took part in August Geib's funeral in Hamburg. The Rote Feldpost , headed by Joseph Belli and Julius Motteler , smuggled agitation pamphlets and, above all, the newspaper Sozialdemokrat, which had been published in Zurich since 1879 , and whose editor-in-chief was Georg von Vollmar. Employees included Karl Kautsky and Eduard Bernstein . The handling of the Socialist Law varied between states and over time. While in southern Germany the milder practice enabled the publication of the theoretical journal Die Neue Zeit from 1883 , in Prussia the persecution practice, which had also become milder there since 1881, was sharpened again from 1886.

The results of the Reichstag elections in particular showed the limited effect of the Socialist Law. The new social security schemes , which also aimed to win workers over to the state, were not very successful in this regard. Although the SAP's share of the vote in the Reichstag elections of 1881 fell to 6.1%, it rose again to over 9% in the Reichstag elections of 1884 . The success also resulted in a significant increase in group members. In the next few years, the fraction's own weight became apparent for the first time. Members of the party's leading group such as Bebel, Friedrich Engels and Bernstein warned of “parliamentary illusions” and the parliamentary group, which had shown greater willingness to compromise on some issues with other parties, managed to limit the influence again. One reason was that the party was able to increase slightly to over 10% in the Reichstag election of 1887 , but since it had lost in some runoff elections, it had fewer members. At a new foreign congress in October 1887 in St. Gallen, August Bebel finally succeeded in asserting his leadership role in the party and parliamentary group, which he was to maintain until his death. On the international level, the Second International was founded at an international workers' congress in Paris between July 14 and 20, 1889 , and despite the persecution, the SAP was considered the most influential socialist party . In Germany, support for the Socialist Law waned more and more, and when the government submitted a new, now indefinite law towards the end of 1889, the proposal was rejected by the Reichstag with a clear majority on January 25, 1890. Even before the exemption law finally expired, the SAP received almost 20% of the votes in the Reichstag election of 1890 , making it the strongest party in terms of number of voters. However, the constituency division ensured that this was not fully reflected in the number of seats. When the Socialist Law finally expired on October 1, 1890, the authorities had banned 155 periodical and 1200 non-periodical publications, pronounced 900 expulsions and sentenced 1,500 people to a total of 1,000 years in prison.

Rise to the mass party

Social base

The end of the 1880s was not only a turning point in terms of organization. During this time there was also a generation change. More important than the old artisan workers were now the professionally well-qualified, advancement-oriented wage workers in industry as the mass base of the movement. However, most of the politically active still had a technical background. The active members often came from the building trade in the broadest sense. The book printers remained important. This social basis meant that bourgeois values played no small role in the social democratic movement. Guiding principles were discipline, eagerness to learn, orientation towards the middle-class family and the corresponding sexuality, belief in progress and growth orientation. Jürgen Kocka speaks of a bridgehead for middle class in the lower class . But he also draws attention to the fact that the anti-bourgeois ideology was not just mere rhetoric. The socialist labor movement was rooted in milieus of life and experience, which set narrow limits to the ambitions for bourgeoisie.

Party organization

Lecturer Rosa Luxemburg (standing fourth from left), August Bebel (standing fifth from left), Friedrich Ebert (left in the 3rd bank of the right bank row)

After the Socialist Act was repealed in autumn 1890, the party changed its name to the Social Democratic Party of Germany at the party congress in Halle . In addition, a new organizational statute was adopted. The party was built on a shop steward system for legal reasons. The organizational basis was mostly formed by workers' electoral associations at the electoral district level. If an electoral district extended over several municipalities, local associations could be founded among them. These associations formed districts and organizations at the level of the member states of the German Reich. The highest organ of the party was the party congress, which also elected the partially remunerated board of twelve people. The board was newly elected at the annual party congress. In practice, however, the members were mostly confirmed in their office. Together with the control commission, the executive board formed the party leadership. Both the executive board and the Reichstag parliamentary group had to carry out the instructions of the party congresses and to give an account. The seat of the party was Berlin. Organ of the party became the Berliner Volksblatt , that a short time later the title Vorwärts - Berliner Volkszeitung. Central organ of the Social Democratic Party of Germany . In addition to various other resolutions, May 1st was declared a permanent holiday for the workers and the party congress instructed the executive committee to develop a new party program.

For reasons of association law, there were no permanent party memberships or contributions in the 1890s. The party initially remained financially dependent on the sale of magazines and other printed matter. But the adherents' ties to their party were substantial. According to the new organizational statute of 1905, the SPD, unlike most other German parties, became a regular member party. A pronounced party life with regular meetings and a ritualized socialist festival calendar tied the members to the party. Their number has been known more precisely since around 1906. The party had about 384,000 members at that time, its number had grown to over a million by 1914.

The increase in membership led to the expansion of the full-time party apparatus from around 1903. There was criticism of this development early on. But given the large number of members, the apparatus was rather small. For the time before the First World War, one cannot speak of a “calcified bureaucracy”, as the paid functionaries were on average around thirty-five years old. Like being an editor in a party newspaper, the position of party secretary was often the only way to earn a living for particularly active members who could no longer find employment in the private sector or in the public service. From 1906 until the beginning of the First World War, the Reich Party School ensured a certain professionalization of the functionaries .

A social democratic milieu emerges

After the Socialist Law expired, the free trade unions affiliated with the party began to reorganize. An umbrella organization was established in 1890 with the General Commission chaired by Carl Legien . The number of union members rose significantly faster than that of party members in the following decades, which gave the union officials considerable political weight. The number of members in the free trade unions was about 300,000 in 1890, in 1913 it was 2.5 million. This made the free unions by far the strongest unions in the empire.

In addition to the party and trade unions, a socialist cooperative and consumer association system ( Centralverband Deutscher Konsumvereine ) formed the third pillar of the socialist workers' movement. In 1911 there were over 1,100 local consumer cooperatives with a total of 1.3 million members.

In addition, a wide-ranging social democratic association developed, starting with the workers' education clubs , through workers ' choirs, clubs of workers' gymnasts and cyclists to free thinkers and cremation clubs. Overall, an organizational system was created that reached from the cradle to the grave. For several years now, research has been speaking of a social democratic milieu in this context . Although the origins reached back to the development phase of the social democratic movement, it now experienced its characteristic form.

Social democracy in the Reichstag elections from 1893 to 1912

| Share of votes and number of seats of the Social Democrats in the Reichstag elections 1871–1912 |

||

|---|---|---|

| year | Share of votes | Seats |

| ADAV together with SDAP | ||

| Reichstag election 1871 | 3.2% | 2 |

| Reichstag election 1874 | 6.8% | 9 |

| SAP | ||

| Reichstag election 1877 | 9.1% | 12 |

| Reichstag election 1878 | 7.6% | 9 |

| Reichstag election 1881 | 6.1% | 12 |

| Reichstag election 1884 | 9.7% | 24 |

| Reichstag election 1887 | 10.1% | 11 |

| SPD | ||

| Reichstag election 1890 | 19.8% | 35 |

| Reichstag election 1893 | 23.3% | 44 |

| Reichstag election 1898 | 27.2% | 56 |

| Reichstag election 1903 | 31.7% | 81 |

| Reichstag election 1907 | 28.9% | 43 |

| Reichstag election 1912 | 34.8% | 110 |

The upswing in social democracy was reflected not least in the results of the elections. In the Reichstag elections of 1893, 1898 and 1903 the party was able to increase its share of the vote. In 1893 it was 23.3%, in 1903 it was over 31%. The special circumstances of the Reichstag election of 1907 (the Hottentot elections ) with their nationalistic undertones and the formation of the Bülow bloc led to slight losses in the proportion of votes. The party suffered a deep slump because of the runoff agreements between the bourgeois parties in the Reichstag mandates. The number of group members almost halved from 81 to 43. However, this slump proved to be temporary; In 1912 the SPD received almost 35% of the vote and had 110 members of the Reichstag. However, these successes were not evenly distributed across the empire. The electoral success depended on the one hand on the social structure; in large and industrial cities the success of the party was many times greater than in the country. Another important factor was the denominational structure. The SPD was strong, especially in predominantly Protestant areas, regardless of the personal attitude of the voters. She found it difficult to gain a foothold in Catholic regions. In the heavily industrialized Rhineland, in the Ruhr area, in the Saar district and in Upper Silesia, many workers remained integrated into the Catholic milieu and voted for the Center Party. In the Protestant part of Germany, too, there was still a considerable number of workers' voters who voted for one of the bourgeois parties.

Internal and programmatic development

It is true that over time the SPD has become a social and political factor that should not be underestimated. Their integration into the existing state and social order remained limited. Even after the Socialist Law expired, the state and the groups that supported it continued to reject the Social Democrats. At times, as in 1894 with the overturn bill or in 1899 with the prison bill, new exceptional laws were planned. With the exception of the Lex Arons , these failed because of the majority in the Reichstag, but just as the establishment of the Reich Association against Social Democracy (1904) strengthened the Social Democrats in their fundamental opposition .

Erfurt program

Inside the party, during the Socialist Law, Marxism prevailed as the dominant ideology over other political ideas, such as those of Lassalle. The official course of the SPD was formulated in 1891 by the Erfurt program adopted at the party congress in Erfurt . Karl Kautsky mainly shaped the basic part, while Eduard Bernstein was responsible for the practical part. This last part with the demands for a democratization of society as a whole and social reforms was formulated more clearly than in the previous programs, but did not differ fundamentally from them. In contrast, the first part, which also contained a sketchy analysis of society, was more clearly oriented towards Marxism than it used to be. The program culminated in the formulation:

“ The Social Democratic Party of Germany is not fighting for new class privileges and privileges, but for the abolition of class rule and classes themselves and for equal rights and obligations for all regardless of gender or origin. Proceeding from these views, it fights in today's society not only the exploitation and oppression of wage workers, but every kind of exploitation and oppression, whether it is directed against a class, a party, a gender or a race. "

"The Young" and the Reformism Controversy

The enforcement of Marxism did not mean an end to internal pluralism or disputes over the right course. Without the pressure of persecution on the one hand and the increase in membership numbers on the other, different currents developed within the party. The party leadership was fundamentally criticized from two sides. In the early 1890s, the left opposition came from the so-called "boys". These criticized, for example, the behavior of the party leadership on May 1, 1890, for not having called for work stoppages to enforce the eight-hour day. Other criticism was directed against the still strong position of the Reichstag faction and the reformists. Because their goals could not be achieved within the SPD, some of the young split off and founded the Association of Independent Socialists, which soon turned to anarchist tendencies under the influence of Gustav Landauer . On the other side of the inner-party spectrum were the reformist forces, particularly from southern Germany. As early as 1891, Georg von Vollmar called for a reform policy based on the existing state and social order and for cooperation with all progressive forces. “The open hand for good will, the fist for bad.” As early as the early 1890s, the Bavarian parliamentary group approved the upcoming budget and the reformists pushed for an agricultural program to broaden the electorate base. Both met fierce opposition from within the party as a whole during the so-called reformism dispute. Ultimately, Karl Kautsky prevailed with his strictly Marxist stance. One consequence of the decision was that the party's electoral potential narrowed more and more to the industrial workers. Agitation in rural regions, on the other hand, was neglected.

The revisionism dispute

Partly following on from the older discussion, partly based on his own theoretical considerations, Eduard Bernstein sparked the revisionism dispute in the party in the second half of the 1890s . A central starting point was the thesis that economic and political developments would by no means automatically lead to the collapse of the system. In view of the social differentiation, Bernstein was also skeptical of the simple reduction of society to the contrast between capital and labor. Instead, he too sought an alliance with the progressive forces of the bourgeoisie. “Its influence would be much greater than it is today if social democracy found the courage to emancipate itself from the phraseology that is actually out of date and seem to want what it really is today: a democratic-socialist reform party . “Ignaz Auer spoke in many respects for the party leadership as a whole when he recognized the character of a social democratic reform party, but with a view to the unity of the party warned against destroying the ideological hopes for the future, which are important for the identity of the party members. "My dear Ede, what you ask for, you don't say something like that, you do something like that." Rosa Luxemburg formulated the decisive opposite position to Bernstein . She did not defend the secret revisionism of the party leadership, but called for a revision of the party line in the direction of revolutionary activism. She rejected reform work in the existing system, as this would only prolong the survival of the bourgeois system. In particular, the functionaries of the strengthened trade union movement resisted this leftist position. Carl Legien said in 1899, “We unionized workers in particular do not want the so-called Kladderadatsch to take place. (…) We wish the state of calm development. ”More important than theoretical considerations for this group was the further expansion of the organization. Both the revolutionary and the reformist perspective were entirely coherent in themselves, but did not correspond to the political reality in the empire. A well-organized state, which could fall back on the army if necessary, stood against a possible attempted violent overthrow. On the other hand, alliances with other parties opposed the deeply rooted anti-social-democratic attitude in large parts of the bourgeoisie. The end of the ultimately fruitless debate came at the party congress of 1903, when it decided, including the revisionists, to continue the "previous tried and tested tactics based on the class struggle."

Mass strike debate and Mannheim agreement

Triggered in particular by the strike of the miners in the Ruhr mining industry and the Russian Revolution in 1905, disputes arose over whether a general strike, as it had already been used in other European countries to enforce political demands, also in Germany, for example in the fight against the Prussian Three-tier voting should be adopted. The opponents in the mass strike debate were the free trade unions or the trade union wing in the SPD on the one hand and a remarkable coalition of the party executive, revisionists and leftists. The trade unions completely opposed political strikes. The trade union congress of 1905 decided by a broad majority: “ The general strike, as it is being represented by anarchists and people without any experience in the field of economic struggle, is considered by the congress to be out of the question; He warns the workers not to allow themselves to be deterred from the daily work to strengthen the workers' organizations by taking up and disseminating such ideas . ”In contrast, the SPD party congress passed a motion in the same year in which the mass strike was seen as an effective means of struggle fend off possible political attacks on the working class. On the other hand, it is an offensive means of liberating the working class.

In order to avoid the break between trade unions and the party, both sides sought a compromise. At the Mannheim party congress in 1906 it was decided that a mass strike without the support of the trade unions could have no prospect of success. This ultimately meant the end of the political concept of a mass strike for Germany. In the so-called Mannheim Agreement, the role of trade unions and the party was redefined. The organizational weight of the unions that had meanwhile acquired forced the SPD to revise the old idea of the unions as a recruiting school for the party and to grant them equal status. " In order to bring about a uniform approach to actions that affect the interests of the trade unions and the party alike, the central managements of the two organizations should seek to come to an understanding ." The question of the mass strike was also the subject of the 1907 International Socialist Congress in Stuttgart. While the French Jean Jaurès spoke out in favor, the German representatives were negative. At the local level, disappointment with the outcome of the debate led to the emergence of the Bremen left-wing radicals .

The social democracy before the beginning of the First World War

In the last few years before the beginning of the First World War, at the party congress of 1910 there was yet another conflict between the southern German reformers and the party majority over approval of the state budgets. However, resistance to cooperation with the bourgeois parties also gradually began to crumble in the Reich Party. Despite criticism from within the party, run-off agreements were concluded with the left-wing liberals before the Reichstag elections of 1912, which greatly contributed to the SPD's great electoral success. Within the SPD, this policy met with decided rejection from the left wing. Outside the party, the conservative forces once again intensified their anti-social-democratic efforts, for example in the form of a cartel of the creative classes . The pressure from the governmental state ultimately prevented positive integration into the existing state and intensified negative integration into a separate social-democratic milieu. In the party itself, after the death of August Bebel, who had shaped the social democratic movement since the 1860s, there was a generation change. The new party leadership was formed by Hugo Haase (from 1911) and Friedrich Ebert (from 1913). Both were not counted among the revisionists or the left wing, but represented the centrist executive line, although there were clear differences between them. The party hoped that both sides would continue the course between the reformist and revolutionary wings.

First World War, division and revolution

Decision for the war credits

When the political situation came to a head in the July crisis in 1914 after the assassination of the Austrian heir to the throne, the SPD called for peace demonstrations without this having had any impact on events. The attitudes of the leading party members to a possible war varied. For the radical left around Rosa Luxemburg it was an inevitable consequence of the imperialist contradictions and an active peace policy was therefore illusory. Overall, there were only a few convinced pacifists in the party leadership. Like Kautsky, Bernstein, Haase and Kurt Eisner, these came from various inner-party camps. A large part of the SPD leadership was convinced by the Reich leadership that Germany was in a defensive war against Tsarist Russia and its allies. The central touchstone for the party's attitude to war was the approval of war credits by the Reichstag parliamentary group. Even before the vote, the right wing decided in favor of acceptance, not least under the impression that the free trade unions had already agreed to the economic truce . In order not to jeopardize the unity of the party, the more left-wing MPs also agreed to the loans, albeit heavily criticized by the union's revolutionaries . In a statement of August 4, 1914, it was said: “Today we did not decide for or against the war, but on the question of the means necessary for the defense of the country.” The right-wing group members added the sentence: “We leave in the hour of danger do not abandon the fatherland. ”On the extreme right of the SPD, the so-called Lensch-Cunow-Haenisch group even raised something like a social-democratic variant of the bourgeois war goal demands.

Party split

However, parts of the party soon realized that the defensive war thesis was wrong. When new war credits became necessary in December 1914, Karl Liebknecht voted openly against the faction majority. As a result, Otto Rühle also joined. Both were then expelled from the parliamentary group. Tensions within the party grew when Bernstein, Haase and Kautsky published a manifesto in 1915 under the title The Commandment of the Hour , which, in view of the annexation plans of the economy, government and parts of civil society, called for an end to war support. As a result, politicians from the more right wing like Eduard David began to think openly about excluding the critics. In December 1915, only 66 voted for and 44 against new loans. In March 1916, opponents of the war, including party leader Haase, were finally expelled from the parliamentary group. These joined together to form the Social Democratic Working Group , but the majority did not intend to split the party . A Reich conference with delegates from both sides in September was supposed to sound out possibilities for agreement. There the opposition made up about 40% of the delegates. However, this failed because of the uncompromising attitude of the majority. In addition, with the Russian February Revolution of 1917, one of the leading arguments for war that was decisive for social democracy no longer existed. In April 1917 the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) was founded in Gotha with Hugo Haase as chairman. It was also joined by Kautsky and Bernstein, the two former opponents of the revisionism dispute.

As early as 1916, the left-wing revolutionary Spartakusbund was founded as a group international under the leadership of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg . The party historian Franz Mehring also joined her. The Spartacus League itself became part of the USPD. He formed the left wing of the party, but continued to pursue an independent policy.

The foundation took place in a heated environment. In April 1917, politically motivated strikes against war and hunger broke out in the USPD strongholds in Berlin and Leipzig. But they also made it clear that the position of the MSPD had lost more and more support in the social democratic electorate. The latter was therefore ultimately forced to correct its attitude. Although she adhered to the principle of national defense, she also pleaded for a quick peace agreement. Not least because of fear of a revolution in their own country, a peace resolution was passed in the Reichstag in July 1917 with the votes of the MSPD, the center and the left-wing liberals . In the run-up, an intergroup of the three parties was established, which formed the nucleus of the later Weimar coalition .

In January 1918 there were protests and strikes by numerous workers against the tough peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk , which revolutionary Russia under Lenin had to conclude. Linked to this were domestic political demands for peace and reforms. Representatives of both social democratic parties joined the strike leadership. These included Ebert, Philipp Scheidemann and Otto Braun on the MSPD side and Haase, Wilhelm Dittmann and Georg Ledebour on the USPD side . They wanted to bring the movement back under control and prevent possible radicalization.

Social Democracy in the November Revolution of 1918

In October 1918, the MSPD, with its representatives Gustav Bauer and Philipp Scheidemann, joined the newly formed government of Max von Baden , which, with the October reforms, carried out approaches to parliamentarization. Although the USPD strongly opposed the support of an imperial government, it did not rely on revolutionary change either, but pleaded for the election of a national assembly . All considerations were initially rendered superfluous by the November Revolution, which spread out from Kiel over the entire Reich . Initially, the workers 'and soldiers' councils , which were formed almost everywhere, were the bearers of the movement. The radical left (Spartakusbund and others) had limited influence in these organizations. Most of the members were close to the Social Democrats (both directions) and the trade unions. The main aim of the councils was not to establish sovereignty based on the Russian model, but rather to end the war, secure the supply situation, disempower military rule and democratize the state.

On November 9, 1918, in order to contain the movement, Max von Baden enforced the abdication of Wilhelm II and formally commissioned Friedrich Ebert with the office of Reich Chancellor against the constitution. Philipp Scheidemann proclaimed the republic against Ebert's will, who was still trying to follow a strict legality course: “The old and the rotten, the monarchy collapsed. Long live the new, long live the German republic! ”At almost the same time, Karl Liebknecht proclaimed the socialist republic.

The MSPD and the USPD formed the Council of People's Representatives on November 10th . Ebert, Scheidemann and Otto Landsberg for the MSPD and Haase, Dittmann and Emil Barth for the USPD were involved. In order to win the USPD into government participation, the MSPD had to expressly recognize the revolutionary foundations of the political new beginning. The Council of People's Representatives announced that political power was in the hands of the workers 'and soldiers' councils and that they should meet for a general assembly as soon as possible.

However, the MSPD resolutely opposed any form of council rule and warned against Bolshevization. The party therefore fought against the staunch left, although their actual support was limited. Against the background of feared further radicalization and the fear of the collapse of the state organization, the MSPD refrained from implementing further reform steps in the first phase of the revolution. Instead, there were agreements between the Supreme Army Command under General Wilhelm Groener and Friedrich Ebert ( Ebert-Groener Pact ). Even declared opponents of the revolution remained in their posts in the government apparatus. The compromise with the old forces meant that they could hold their own. After the consolidation of the situation, later democratization and republicanization, especially of the military, was hardly possible.

The announced meeting of the workers' councils took place as the so-called Reichsrätekongress in mid-December 1918. The majority of the delegates of almost 60% were close to the MSPD. Despite some more far-reaching decisions such as the socialization of industry, the assembly essentially supported Ebert's policy and, against the will of the USPD, which wanted to convene a national assembly as late as possible in order to still be able to create facts according to revolutionary law by then, the election date was set to 19 January 1919. This was not acceptable to the radical wing of the USPD, which was oriented towards the October Revolution. Not least for this reason, at the turn of the year 1918/19, the KPD split off as an independent party from the USPD.

There were violent conflicts between the USPD and the MSPD over the competences of the central council decided by the Reichsrätekongress . The coalition finally failed because of the question of the deployment of the military at Christmas 1918. After the USPD left the government, Gustav Noske (MSPD) joined the committee. During the so-called Spartacus uprising in January 1919, Noske took on the task of suppressing the uprising with the words: “Someone has to do the bloodhound.” Although there were republican protection troops at that time, he resorted to Freikorps . They brutally suppressed the uprising, and their officers, who were close to the extreme right, also ordered the murder of numerous politicians and supporters of the KPD - probably with the tolerance of Noske and others. Among these were Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht.

In the election for the German National Assembly , the hopes of the Social Democrats for an absolute majority and thus a large amount of political freedom to make decisions were not fulfilled. The MSPD came in at 37.9% and the USPD at 7.6%. Together this was 45.5%. Instead of the hoped-for workers' government, the MSPD, the Catholic Center Party and the left-liberal DDP formed the so-called Weimar Coalition .

Social democracy and political radicalization 1919/1920

The Weimar National Assembly voted on 11 February 1919 the former Chancellor Friedrich Ebert provisionally Reich President . This was the first time that a Social Democrat was German head of state. Ebert kept the office until his death in 1925. Phillipp Scheidemann took over the position of Chancellor. Otto Wels and Hermann Müller took over the chairmanship of the SPD .

Not least the violent crackdown on the left opposition in late 1918 and early 1919 led to a radicalization of the workers 'and soldiers' councils. In the spring of 1919 there were strike movements, especially in the Ruhr area and Central Germany, in which, in addition to the enforcement of wage demands, the announced socialization of the economy was demanded. In some federal states ( Bavaria , Bremen ), council republics emerged, which were finally dissolved by the government led by the majority Social Democrats with the regular military and voluntary corps.

| Share of votes of the SPD in the election to the National Assembly in 1919 and in the Reichstag elections 1920–1933 |

||

|---|---|---|

| year | be right | |

| Election to the German National Assembly in 1919 | 37.9% | |

| Reichstag election 1920 | 21.7% | |

| Reichstag election May 1924 | 20.5% | |

| Reichstag election December 1924 | 26% | |

| Reichstag election 1928 | 29.8% | |

| Reichstag election 1930 | 24.5% | |

| Reichstag election July 1932 | 21.6% | |

| Reichstag election November 1932 | 20.4% | |

| Reichstag election in March 1933 | 18.3% | |

One consequence of the shift to the left in the working population was that the USPD received influx not only from disappointed members of the MSPD, but also from many previously unorganized workers. The membership grew from 300,000 in March to 700,000 in November 1919. However, this success masked the internal tensions between their left and right wings.

The MSPD faced the question of whether to accept the Versailles Treaty in government . Reich Chancellor Scheidemann, who was unable to assert himself with this stance and therefore resigned, was strictly against it. Ultimately, the majority of the parliamentary group in the Reichstag was forced to approve for lack of alternatives. The political right took advantage of this decision in the following years for propaganda purposes and defamed the SPD as a “ November criminal ”. Scheidemann's successor as head of government was Gustav Bauer (June 21, 1919 to March 27, 1920). In March 1920 the existence of the republic was threatened for the first time from the right by the Kapp Putsch . However, the putschists failed because of the general strike by the unions. The hopes of a workers' government , which were at times renewed by the trade unions , were of course not fulfilled. In the Ruhr area, partly left-wing socialist , partly communist-oriented workers continued the strike that developed into the so-called Ruhr uprising . With the help of troops that had recently been on the side of Kapp, the new government under Hermann Müller had the uprising broken by force.

The Kapp Putsch and the Reichstag elections of June 1920 represent a deep turning point in several respects. The initial revolutionary phase of the republic came to an end. In the Reichstag election, the MSPD lost significantly (21.7%), while the USPD (18.8%) was almost on par. This once again confirmed the left swing in the social democratic camp. Since there was a clear shift to the right in the bourgeois camp, the Weimar coalition had lost its majority and the SPD became an opposition party. The year 1920 was also a turning point for the social democratic movement because the majority of the USPD decided to convert to the Communist International and to merge with the KPD at its party congress . Only since then has it been a mass party. The rest of the USPD initially remained independent; in the following years it was crushed between the MSPD and the KPD.

Social democracy in the Weimar Republic

In the years following the end of social democratic political dominance, the SPD only took part in coalition governments led by other parties until 1924. It was only in 1928 and until 1930 that she once again appointed Chancellor Hermann Müller. In the final phase of the republic she was again in the opposition.

Expansion and limits of the socialist milieu

The continuing importance of the pre-war structures is supported by the fact that the number and scope of socialist subsidiary organizations increased significantly after the First World War. In many cases, social democrats and communists were represented together in them for a long time. However, there is the thesis in research that the binding effect of these organizations has waned in the face of competing leisure activities such as cinema, radio or mass sports events. Numerous organizations were only founded after 1919. These included the Arbeiterwohlfahrt , the Jusos , the Socialist Workers' Youth (SAJ), the Kinderfreunde , the Arbeiter-Radio-Bund Deutschland , but also organizations for teachers, lawyers, tradespeople, vegetarians and numerous other groups. The old organizations expanded significantly. The Workers' Gymnastics and Sports Association grew from 120,000 to 570,000 members. The proletarian freethinker association rose from 6,500 to 600,000 members. Geographically, the club system now also reached places where it was not yet represented before the war. However, there were still big differences between town and country or between Catholic and Protestant regions. The development was also irregular in terms of time. The hyperinflation plunged the organizations into a deep crisis, but they were mostly able to recover by 1926 and grew rapidly in the following years before another slump occurred with the global economic crisis. At the end of the republic, the competition between the SPD and KPD also affected the organizations in different ways. Despite all the external similarity, the demarcation from the bourgeois associations remained large. The socialist and Marxist view of the world remained strong. Overall, there have been attempts to soften the socialist milieu, but these tendencies have remained limited. Even during the republic, social democratic families and neighborhoods ensured that the milieu was reproduced alongside the associations. However, there were considerable differences in ties, which is also reflected in the fluctuations in club life. In addition, there were numerically rather insignificant currents that were somewhat remote from the classic working class environment, but were of importance for later development. This included, for example, religious socialism , some of whose supporters were organized in the League of Religious Socialists in Germany .

Politics in the municipalities and in the states

In the Weimar Republic, politics did not only take place at the national level. In the municipal area, social democrats were able to take on political responsibility after the end of the three-class franchise in Prussia and comparable restrictions in other countries. Depending on the electoral structure, the political significance in the countries varied.

In Prussia, which is by far the largest country, the SPD under Prime Minister Otto Braun was able to maintain its political supremacy into the final phase of the republic. Between 1919 and 1932 the SPD provided the government with brief interruptions and shaped it as a leader. Politicians like Carl Severing built the former authoritarian state with republican reforms in the police and administration into a democratic bulwark of Prussia against the extreme right and left. Although the reforms of what contemporaries referred to as the Braun-Severing system had clear limits, they had changed Prussia significantly. With the so-called Prussian strike in 1932, social democratic supremacy also ended in this country.

Another example of the sometimes strong power of the SPD in the federal states is Saxony, where the SPD consistently had the strongest parliamentary group and never fell below the 30% mark. In contrast to this, it was often the strongest or second strongest force in Württemberg , for example , but had not been part of the government since 1923. In neighboring Baden , the SPD managed to participate in a Weimar coalition from 1918 to 1930 and beyond with the center and DVP until 1932. In the People's State of Hesse , the SPD ruled at the head of a Weimar coalition from 1918 to 1933. In Bavaria, however, the government lasted SPD in various coalitions only from November 1918 to March 1920.

The development up to the crisis years 1923/24

As early as 1921, the SPD returned to government in a coalition government under the center chancellor Joseph Wirth . At its Görlitz party congress in the same year, the SPD adopted a new program. The Görlitz program expressly committed itself to the Weimar Republic. "They regarded the democratic republic as the irrevocable given by the historical development of government, any attack on them as an attack on the right to life of the people." The program included Ideologically still some Marxist elements - it kept as fixed in the class struggle concept - but it was clearly more revisionist than the Erfurt program. In retrospect, it is important because the party no longer only focused on the industrial workers, but saw itself in the manner of a people's party as the party of the working people in town and country .

| Social democratic participation in the Reich government (“R” for government) 1918–1933 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Art | cabinet | Duration |

| October 3, 1918– November 9, 1918 | R participation | Baden cabinet | 1.2 months |

| November 10, 1918– February 13, 1919 | R-Chair | Council of People's Representatives | 3 months |

| February 13, 1919– June 20, 1919 | R-Chair | Scheidemann cabinet | 4.2 months |

| 06/21/1919– 03/27/1920 | R-Chair | Cabinet peasant | 9.2 months |

| 03/27/1920– 06/21/1920 | R-Chair | Cabinet Müller I | 2.8 months |

| May 10, 1921– October 22, 1921 | R participation | Cabinet Wirth I. | 5.4 months |

| October 26, 1921– November 14, 1922 | R participation | Cabinet Wirth II | 12.6 months |

| August 13, 1923-04 October 1923 | R participation | Cabinet Stresemann I | 1.7 months |

| October 6, 1923– November 23, 1923 | R participation | Cabinet Stresemann II | 1.5 months |

| 06/28/1928– 03/27/1930 | R-Chair | Cabinet Müller II | 21 months |

The hope of gaining new electorate was not entirely unrealistic, as immediately after the end of the war, social democracy was able to attract not a few farm workers in eastern Germany, but also small and medium-sized civil servants and employees. In the medium term it was only able to bind these groups to a small extent, and the SPD remained essentially a classic workers' party. This was also due to the fact that the popular party revisionist course in the party was soon no longer capable of receiving a majority. The reason for this was that the majority of the rest of the USPD returned to the SPD in 1922, which they significantly strengthened their left wing. The reunification meant a considerable strengthening of the party. It now had 1.2 million members and held 36% of the seats in the Reichstag. The hope for calm political development after the end of the revolutionary years was not fulfilled. The political murders from the right of Matthias Erzberger and in 1922 of Walther Rathenau led to the convergence of the democratic parties, before the state fell into another deep existential crisis in 1923. The occupation of the Ruhr led to violent protests across all party lines . The costs of the passive resistance announced by the government were also the last trigger for a hyperinflationary development up to the almost complete depreciation of the German currency. After a short time in the opposition, the SPD returned to the government under Chancellor Gustav Stresemann because its leadership was of the opinion that the crisis could only be overcome on the basis of a broad alliance. The different behavior of the government, on the one hand the execution of the Reich against the social democratic-communist coalition government in Saxony and on the other hand the acceptance of the anti-republican regime in Bavaria, led to the exit of the SPD from the Reich government.

The threat to the republic from the right led to the establishment of the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold as an organization to protect the republic in early 1924 . Although officially non-partisan, the great majority of the members of the SPD were close.

The stabilization policy, partly with the consent of the SPD, was bought at the price of a massive lowering of real wages and the abolition of key achievements of the revolution such as the restriction of the eight-hour day or the end of institutionalized cooperation between trade unions and employers in the central working group . The SPD as the state party of the first Weimar years was (not really rightly) assigned a high degree of responsibility by the voters for the social hardship during and after the inflation. The workers' voters often went over to the KPD. Whereas in 1920 both social democratic parties still got over 40% of the voters, in the first Reichstag election in 1924 it was only 20.5%. In contrast, the KPD's share increased significantly from 2.1% in 1920 to 12.6%. The outcome of the elections in December 1924 , when the KPD suffered losses mainly in favor of the SPD , shows how dependent the will of the electorate was on the current situation . Taken together, the camp of the labor parties (USPD, MSPD, KPD) lost considerable support from 1919 (45.5%) to December 1924 (34.9%).

Social democracy in the middle phase of the republic

The party was no longer needed for the formation of a government, and so the bourgeois parties together with the center dominated politics in the following years. The election of the Reich President , which became necessary after the death of Friedrich Ebert, was characteristic of the change in the political climate . The first ballot brought a 29% share of the vote for the SPD candidate Otto Braun . However, in the second ballot, not the SPD-supported candidate Wilhelm Marx , but Paul von Hindenburg - a representative of the German Empire - was elected.

The loss of government responsibility in the Reich, but also the integration of the former USPD members, led to the tradition of a solidarity community of industrial workers prevailing again in the party. This is clearly reflected in the Heidelberg program of 1925, which was largely based on the Erfurt program and the Marxist positions of the prewar period. There it says: “The transformation of capitalist production into socialist production operated for and through society will have the effect that the development and increase of the productive forces will become a source of the highest welfare and all-round perfection. Only then will society rise from submission to blind economic power and from general disunity to free self-government in harmonious solidarity. ”In the field of international politics, the party called for the creation of the United States of Europe and a European economic unit. The withdrawal to the target group of industrial workers was not only for ideological reasons. Rather, this was also a reaction to the fact that the party had not succeeded in binding the farm workers, employees and civil servants who had been won over immediately after the November Revolution. The founding of the Old Social Democratic Party of Saxony (ASPS, later ASPD) in March 1926 by 23 members of the Saxon state parliament excluded from the party and belonging to the right wing of the party did not weaken the SPD outside of Saxony.

Even if the impetus for the referendum on the princely fortunes in 1926 came from the KPD, the SPD also showed itself capable of campaigning. For the political left, this movement was a great success. The 14.5 million yes votes were 4 million more than the SPD and KPD achieved in the last Reichstag election. The recovery of the SPD was impressively confirmed in the Reichstag election of 1928, when the SPD gained considerably and received almost 30% of the votes. In doing so, she succeeded in penetrating the camp of Catholic workers to an appreciable extent, most of whom had previously voted for the center. The Müller II cabinet under Reich Chancellor Hermann Müller emerged from the elections . This grand coalition was riddled with potential ruptures from the start. There were great social and economic differences between the SPD and the DVP, which is strongly influenced by industrial interests. The relationship to the center, which after the elections was oriented more to the right, was also problematic. Even within the SPD there were quite a few who refused to participate in government again and warned against the necessary compromise decisions. The conflict over the ironclad A became an acid test. While the SPD had fought against this project during the election campaign, the social democratic wing of government was now forced to give its approval for various reasons, which led to considerable protests within the party. The first tensions between the coalition partners broke out with the great lockout in the dry iron dispute . From the left the SPD was defamed as social fascists by the KPD, which at that time was in its so-called ultra-left phase, and the communists intensified the separation and establishment of their own organizations in the trade unions and socialist associations. The KPD was strengthened by the violent smashing of a forbidden May demonstration ( Blutmai ) on the orders of the Social Democratic Berlin Police President Karl Zörgiebel in 1929. In March 1930, the cabinet broke up in the dispute between the SPD and DVP over different attitudes to unemployment insurance.

The SPD on the defensive since 1930

The end of the Müller government also meant the end of the parliamentary system of government. Even his successor Heinrich Brüning ultimately relied on the authority of the Reich President and Article 48 of the Reich Constitution.

The end of the republic was shaped economically by the effects of the global economic crisis , which, unlike earlier economic fluctuations such as 1925/26, could not be overcome after a few months, but plunged the economy into a crisis for years. This led to a massive increase in the unemployed and widespread social hardship.

Nevertheless, Brüning's deflationary policy, which was associated with massive austerity measures, was essentially supported by the SPD, even though it pushed for a fairer distribution of the burdens. The dissolution of the Reichstag and the new elections in 1930 weakened the moderate parties and strengthened the radicals; the Social Democrats lost over 15% of their votes. The NSDAP , which had previously been little more than a splinter party, was able to establish itself as the second strongest political force with over 18% of the vote.

In the years that followed, the SPD was increasingly on the defensive. She opted for a long-term tolerance of the Brüning Presidential Cabinet (“constructive opposition ”) in order to prevent further early elections after the shock of 1930. The party hoped to prevent the NSDAP from drawing closer to Brüning or from governing beyond the constitution. This compromise policy was not attractive to its own supporters, but also to potential voters. In view of the social hardship, younger workers in particular went over to the KPD or, to a certain extent, the NSDAP.

After all, the SPD, together with the free trade unions and the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold, tried since 1931 to oppose a republican-oriented protection formation to the SA and the Red Front Fighters League of the KPD with the Iron Front . As impressive as the mass marches were, the organization had little influence on developments.

Inner criticism and new organizations

For many members, but also in large parts of the left-wing public, the party leadership's policies met with sharp criticism. There were also calls for a united front between the SPD and KPD and for overcoming the split in the Marxist labor movement.

The policies of the grand coalition had already met with severe criticism from the party's left wing. These tendencies intensified against the background of the policy of tolerance. Eventually, the left protagonists Max Seydewitz and Kurt Rosenfeld were expelled from the party. Together with other critics, the Socialist Workers' Party (SAP; partly also called SAPD) was founded in 1931 , in which the USPD, which had previously existed as a small party, was merged under its last chairman Theodor Liebknecht . The goal of SAP was to create a unified revolutionary organization on a national and international basis. The new party clearly distinguished itself from the SPD and the KPD. The party had several priorities, for example in Leipzig, Dresden or Breslau. She also received support from left-wing intellectuals such as Albert Einstein and Lion Feuchtwanger . It was successful in parts of the socialist youth movement. Herbert Frahm (later Willy Brandt ) came from this environment. The party exerted a certain attraction on members of left factions like the USPD and KPO . However, it did not succeed in winning over the left wing of the SPD as a whole, nor in gaining any significant influence among the voters. In the Reichstag elections of July 1932 it only got 0.2% of the vote.

Within the SPD, the party's course was also criticized by the so-called New Right, which later included a number of influential younger functionaries and members of parliament ( Carlo Mierendorff , Julius Leber , Theodor Haubach , Kurt Schumacher ). These demanded that the party should again become a power factor outside of the parliamentary stage. Above all, it should not only take a defensive position, but aggressively spread a socialist vision for the state, economy and society. The party leadership saw this as an attack on tried and tested ideology and tactics as well as youthful arrogance. Internal criticism hardly changed the party's course.

Social democracy at the end of the republic

The presidential election of 1932 shows how far the policy of tolerance went . From the beginning, the SPD renounced its own candidate and, out of fear of a Reich President Adolf Hitler , spoke out in favor of the re-election of the more anti-republican Paul von Hindenburg. After his re-election, the extremely conservative Franz von Papen was appointed Reich Chancellor, from whom no return to the parliamentary system was to be expected. Rather, he made sure that the SPD lost one of its last influential political positions. In 1930 the DNVP and KPD submitted a joint motion of no confidence in the Prussian parliament, in 1931 the Stahlhelm tried to push through a referendum to remove the government in Prussia with the support of the NSDAP , DNVP, DVP and KPD. In the state elections on April 24, 1932, the Prussian government coalition around Otto Braun lost its parliamentary majority and has only been in office since then. Von Papen took advantage of this situation on July 20, 1932, during the so-called Prussian strike . The government was deposed, and von Papen appointed himself State Commissioner in Prussia. A possible general strike like the one in the Kapp Putsch in 1920 was out of the question because of unemployment. While there was great willingness in parts of the Iron Front to take action against the Prussian strike, even with force if necessary, the party leadership refrained from taking this step.

In addition to the ongoing social hardship, the disappointment with the indecisive behavior of the party leadership meant that the SPD continued to lose weight in the two Reichstag elections of 1932. In the July election , it was slightly more than 21% behind the NSDAP. The NSDAP lost in the November election. But the SPD again suffered slight losses, which mainly benefited the KPD. At almost 17%, this was only just behind the SPD.