Social market economy

The social market economy is a societal and economic policy model with the aim of " combining free initiative on the basis of a competitive economy with social progress that is guaranteed by economic performance".

The term social market economy goes back to Alfred Müller-Armack , who saw it as an Irish formula, the meaning of which is to "combine the principle of freedom in the market with that of social equality". The concept is based on ideas that were developed in the 1930s and 1940s with quite different emphasis. Ordoliberalism stands out from this historical background , in particular Walter Eucken , Franz Böhm , Alexander Rustow and Wilhelm Röpke . Compared to ordoliberal ideas, the concept is characterized by greater pragmatism, for example in economic and social policy .

Social market economy has established itself as the name for the economic order of the Federal Republic of Germany , the Republic of Austria and Switzerland . The social market economy was agreed in the State Treaty of 1990 between the Federal Republic and the GDR as a common economic order for the monetary, economic and social union and is propagated as an “export hit”. According to the Lisbon Treaty, the European Union is striving for a “competitive social market economy” with full employment and social progress. In the international context, the economic order is sometimes referred to as Rhenish capitalism . The term is partly in need of interpretation and is sometimes also viewed as a political catchphrase because of its ambiguity .

term

Emergence

Alfred Müller-Armack chose this combination of words for the first time in 1946 in his work "Economic Control and Market Economy", which was finally published in 1947. He designed the social market economy as a “third form” alongside a purely liberal market economy and state economic control. For the economic order of Germany, which was destroyed by the war, the market should be embedded as a “supporting structure” in “a consciously controlled and socially controlled market economy”. The attempt to "combine the principle of freedom on the market with that of social equilibrium" was what Müller-Armack described as an " Irish formula".

Distribution by the CDU

At first the term was hardly used. It was not until 1949 that the term became known to a wider public as the self-designation of the economic policy of Ludwig Erhard and the CDU through the Düsseldorf guiding principles ( CDU program for the 1949 federal election ). The new economic policy catchphrase “social market economy”, which the CDU placed in opposition to “unsocial planned economy”, was initially controversial. From the social democratic and trade union side, but also from the workers' wing of the CDU, the combination of words was criticized as a euphemism and a purely propagandistic catchphrase. The entrepreneurial and economic liberal side feared that the attribute “social” would arouse expectations that would run counter to economic progress or German competitiveness. The diverse language criticism, however, could not prevent the political success of the catchphrase, with which election campaigns were contested and won, especially in the 1950s.

In West Germany , the term was raised to the guideline of government policy in 1949–1966 and again in 1982–1998 and later promoted as an “export hit”.

Takeover by the SPD and wide acceptance

The SPD initially consistently avoided the use of this flag word and propagated the competitive term of “ democratic socialism ”. In 1949 she even spoke of the “meaningless word of the social market economy” in her election call. With the Godesberg program of 1959 in particular, however, the SPD increasingly adopted elements of the social market economy. The SPD has only been using the term in its programmatic writings since the 1990s. The German Federation of Trade Unions has only used it since its Dresden basic program of 1996. A positive reference to the social market economy has since been widespread across political borders.

Spectrum of meaning

The broad social reference to the term social market economy does not mean that everyone agrees on what is meant by social market economy.

Many scientific and political publications assume an actual original meaning. Reference is often made to the origins of the history of ideas, the currency union, the political / corporatist reactions to the Korean boom and the socio-political course of the 1950s. Just as many publications assume a plurality of justifiable meanings that exist in parallel and / or in chronological order without any actual meaning being discernible. Finally, the evaluation is also represented as an empty formula with no real meaning.

Authors such as B. Knut Borchardt , Roland Sturm and Martin Nonhoff emphasize the open, dynamic character of a compromise formula and argue that “social market economy” cannot be reduced to an actual meaning. Rather, it should be thought of as the continuously evolving result of a dynamic process. Due to the plurality of origins - Müller-Armack's original conception in "Economic Control and Market Economy", Erhard's ideas and those of the CDU in the Düsseldorf guiding principles - a definitive justification of the origin is not possible. The possible predecessors of the conception of the social market economy are by no means congruent with each other, but “full of points of friction and formidable contrasts”. According to this, “social market economy” is not only a political and politically interpreted term in its present form, but also according to its original interpretation.

According to Hans-Hermann Hartwich, there is a self-contained, theoretical concept of a “social market economy” that has been mixed up with a “popular but completely non-binding idea of a social market economy” through a political discourse shaped by election campaigns . The result is not an empty formula, but something new.

According to Dieter Cassel and Siegfried Rauhut, there is an origin meaning. The social market economy, however, is "largely discredited and degenerated into an empty formula ". You plead for a return to such an original meaning.

Name for the economic order of the Federal Republic of Germany

Since the 1950s, the term social market economy has also become a term for the real economic order of the Federal Republic of Germany. In practice, however, the economic policy of the various federal governments was based on changing political objectives.

Most authors assume that the social market economy has continued to develop since 1948 without the fundamental characteristics of the economic system having changed. Others are of the opinion that the real economic order no longer corresponds to Ludwig Erhard's ideas since 1957 or since the 1960s .

According to Michael Spangenberger , it has been possible to "internationalize the content of the social market economy in the concept of 'Rhenish capitalism'". In order to differentiate the corporative or coordinated market economy that emerged in the countries bordering the Rhine as well as Scandinavia and Japan from the Anglo-Saxon economic systems, Michel Albert introduced the term " Rhenish capitalism " in 1991 , assigning the social market economy to Rhenish capitalism. Gerhard Willke sees the social market economy or the synonymous Rhenish capitalism as a model of capitalism that is characterized by a moderate degree of regulation. He contrasts this with the alternative capitalism models of the poorly regulated free market economy on the one hand and the highly regulated managed economy on the other hand and comes to the conclusion that efficiency, prosperity and quality of life are highest in the capitalism model of the social market economy. For Herbert Giersch , the social market economy or Rhenish capitalism, which he attributes “a touch of communitarianism ”, was symbolized in the 1950s and 60s by personalities such as Konrad Adenauer or leading representatives of Deutschland AG such as Hermann Josef Abs . In contrast, he sees Erhard, Eucken and Hayek , whom he identifies with a “pure capitalism” or a “neoliberal market economy”. Even Manfred G. Schmidt sees the economic system of the Federal Republic of Germany marktwirtschaft foreign features, particularly in terms of the average government expenditure ratio and an average density of economic regulation, which therefore differed from the original model of the social market economy. He suspects that for many observers the term “social market economy” is not sufficiently selective and that they would prefer terms such as “organized”, “German” or “Rhenish capitalism” to describe the economic order. Gero Thalemann, on the other hand, after a thorough empirical examination of the basic values and goals, comes to the conclusion that the social market economy for the German economy can generally be viewed as a "realized concept".

The concept and characteristics of the social market economy

The social market economy tries to combine the advantages of a free market economy , in particular a high efficiency and supply of goods, with the welfare state as a corrective, which is supposed to prevent possible negative effects of market processes. Its design elements include free pricing for goods and services on the market, private ownership of means of production and the pursuit of profit as an incentive to perform. By creating a legal framework, personal freedoms such as trade , consumption , contract , occupation and freedom of association are to be guaranteed. At the same time, state competition policy should secure competition and prevent private market power (monopolies, cartels) if possible. The basic idea is that the market economy can only develop its prosperity-enhancing and coordinating function if it is committed to competition through a strict state regulatory policy . The state should supplement and correct market events by actively intervening in the economy (for example through social policy , economic policy or labor market policy measures) if this is deemed necessary in the general interest. The socio-politically oriented correction of market incomes should, however, be limited to the extent that the functionality of a competitive economy is not impaired and the individual responsibility and initiative of the citizens must not be paralyzed by a supply state, but the specific demarcation remains open. “Even the criterion of market conformity proposed for the special case of procedural policy measures, however, still needs to be interpreted in individual cases”. Müller-Armack is usually named as the originator of the concept, Erhard's merit lies in the economic policy implementation of the social market economy in the post-war period .

Authorship of the concept of the social market economy

In the opinion of Otto Schlecht , who had worked in the Federal Ministry of Economics since 1953, alongside Walter Eucken and Ludwig Erhard, especially Alexander Rustow, Wilhelm Röpke, Franz Böhm, Friedrich A. Lutz , Leonhard Miksch and Fritz W. Meyer were the intellectual fathers of the social market economy call. Special mention should also be made of Alfred Müller-Armack, who expanded and supplemented the world of the ordoliberals and Ludwig Erhard. According to Hans-Rudolf Peters , who worked in the Federal Ministry of Economics from 1959 to 1974, the theoretical model of the social market economy was mainly designed by Alfred Müller-Armack. Müller-Armack's concept of the social market economy, however, remains rather nebulous. Although the conceptual part “market economy” is relatively precisely defined due to the advance work of ordoliberalism, the social conceptual part lacks a solid theoretical foundation. According to Peters, Erhard and Müller-Armack were in agreement on questions of competition policy; as far as the type and scope of the social tasks are concerned, however, “fundamental” differences of opinion can be identified. Erhard was basically more of an ordoliberal than a social market economist, because he was convinced that market-based prosperity would shrink social problems to a minimum for all. Müller-Armack himself was of the opinion that the overall economic concept of the social market economy was primarily developed by Ludwig Erhard.

On the other hand, a number of authors deny a theoretical contribution by Ludwig Erhard to the social market economy. The text War Financing and Debt Consolidation (1944), in which Erhard describes the design of a post-war order, is rated by the Erhard biographer Volker Hentschel as a “rough sketch”. According to Uwe Fuhrmann, Erhard was an advocate of the "free market economy" and thus contradicted Müller-Armack's dualistic conception, which understood economic and social policy as two equally weighted targets.

Alfred Müller-Armack

Alfred Müller-Armack deserves special mention as the spiritual father of a socially structured market economy, who from 1952 as head of the policy department of the Federal Ministry of Economics and from 1958 at the same time as state secretary as a colleague of Ludwig Erhard not only coined the term social market economy, but also - with others - systematically developed the concept. Müller-Armack developed the theoretical basis of his concept when the “Research Center for General and Textile Market Economy” at the University of Münster was relocated to the Sacred Heart Monastery in Vreden from 1943 due to the war .

Müller-Armack had deliberately left the exact design of the model of the social market economy open because he was of the opinion that framework conditions can change and that an economic system must adapt dynamically to them: "Our theory is abstract, it can only be publicly implemented when it gets a concrete meaning and shows the man on the street that it is good for him. ”This legitimation function explains why there is no closed theory of the social market economy, but rather a program that has grown in individual steps. This evolutionary-compromising basic structure of the Müller-Armack approach necessarily led to tensions in relation to the ordoliberal theory in the course of time.

Shaped by Christian social doctrine and Wicksell's business cycle theory , he most clearly represented the idea of state influence on the results of the market economy. Müller-Armack saw the social market economy as a third form besides the purely liberal market economy and the steering economy : “We speak of 'social market economy' to characterize this third form of economic policy. This means that the market economy seems necessary to us as the supporting framework of the future economic order, only that this should not be a liberal market economy left to its own devices, but a consciously controlled and socially controlled market economy ”. Müller-Armack was concerned with an “ institutional anchoring of their dual principle in the economic order”, which he understood as “bringing the diverging objectives of social security and economic freedom to a new kind of balance”. The trend-setting purpose of the social market economy is to "combine the principle of freedom in the market with the principle of social equality". He called the social market economy an Irish (peace-making) formula that tries to "bring the ideals of justice, freedom and economic growth into a reasonable balance."

According to Karl Georg Zinn, Müller-Armack is closer to the teachings of Wilhelm Röpke and Alexander Rüstow than to those of the purist Eucken, who is a purist of order theory. He gave “social policy and state economic and structural policy a far greater weight than Eucken, for whom social policy seemed necessary at best as a minimal program against extreme grievances and considered economic policy to be simply superfluous, even harmful, because an ideal market economy like him In his order theory, he meant that he would have no more cyclical business cycles and crises at all. ”The following table compares the concepts of ordoliberalism and Alfred Müller-Armack's central economic policy idea of the social market economy based on the work of Josef Schmid:

| Ordoliberalism (Eucken) | Social market economy (Müller-Armack) |

|---|---|

| Pure regulatory policy | Regulatory and process policy |

| Qualitative economic policy | Also quantitative economic policy |

| Strictly scientific concept with clear theoretical boundaries | Pragmatic approach; soft demarcation; Individual decisions |

| Deriving all problem solutions from maintaining order | Furthermore, the need for state intervention to create social equilibrium or to correct market results |

| “Correct” economic policy removes the need for social policy | Separate areas of economic and social policy; Attempt to balance "freedom" and "(social) security" |

| Static concept | Continuous development; Adaptation to new challenges |

Müller-Armack advocates “social interventions” by the state, provided that they are “subject to the principle of market conformity”, which means that only those political measures are taken “that secure the social purpose without interfering with the market apparatus”. Ingo Pies comes to the opinion that, according to Müller-Armack, it can be stated very precisely what politics should not do. But in a positive sense, this principle can only guide the choice of the method of political intervention, not the degree of its application. Heiko Körner takes the view that Müller-Armack made "no concrete statements about the principles and elements of a 'market-compliant social policy'" and that "every interpreter of this 'open-ended model' weighting according to his interests and political preferences" in the area of tension between economic efficiency on the one hand and social justice on the other hand. Nonetheless, Müller-Armack “theoretically” considered the greatest conceivable redistribution of income possible, “without coming into conflict with the rules of the market”.

When Müller-Armack propagated a second - socio-political - phase of the social market economy at the end of the 1950s, he had an expansion of social policy beyond its traditional core with regard to the provision of public goods in the areas of education and health, urban planning and energy and environmental issues as well further questions in mind. In 1975, Müller-Armack formulated a haunting criticism of the advance of democratic socialism, an interventionism that burdens the economic and political framework of the social market economy, in which a number of individual measures are used to bring about a fundamental change that is directed against the core of the market economy. Among these anti-market regulations, Müller-Armack includes parity co-determination and the demand for a redistribution of assets .

Leonhard Miksch

Less well known is the role of the social democrat and ordoliberal Eucken student Leonhard Miksch in the emergence of the social market economy. With his habilitation thesis “Competition as a task” (1937), in which he declared the competition a “state event”, he was “a representative of the Freiburg School and ordoliberalism in the narrower sense”. A few months after he was appointed institutional successor to Walter Euckens at Freiburg University, he died at the age of 49.

From the beginning of 1948 Miksch Erhard was the closest employee in the Frankfurt Economic Council (the predecessor of Müller-Armack, so to speak) as head of the department for “Basic pricing issues and business administration”. Long before Erhard he used the term “social market economy”: at the end of 1947 in a specialist journal and in January 1948 in an internal memorandum “in which he made the linguistic change from the 'free' to the 'social' market economy”, while Erhard continued until the middle 1948 spoke of "free market economy" or simply of "market economy".

Above all, it was Miksch, "who became the pioneer of the price-political support of the currency reform and who gave Erhard's ideas". He “drafted the first principles of economic policy for the transition period following the currency reform”. Because, according to Gerold Ambrosius , "the draft of the 'guiding principles law' [...] almost literally agreed with Miksch's 'principles' [...]". Therefore, according to Ambrosius, "it is not without irony that the bill of all things, which was to have a decisive influence on the further development of the western zone and the federal republic under Christian-Democratic leadership as well as the economic program of the Union, was drafted by a social democrat" ⸮

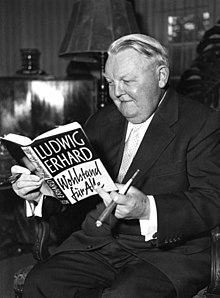

Ludwig Erhard

Ludwig Erhard , who is usually seen as the executor of the social market economy, took the view: "The freer the economy, the more social it is." For Erhard, maintaining free competition was one of the most important tasks of the state based on a free social order. Free competition is the best way to create wealth across societies. As a result, in a market economy that is properly managed in terms of regulatory policy, the need for traditional social policy is decreasing due to increasing prosperity. His vision was the utopia of a depoletarianized society of property citizens who no longer needed social security.

Erhard was much more committed to the liberal and market economy component than the creators of the theoretical concept of the social market economy. However, Erhard used the integration effect in favor of an overall market economy, which could be achieved with this label in a controversial political environment after the Second World War. For Erhard, freedom was superior to all forms of state control and tutelage and, moreover, indivisible. And according to Hans-Rudolf Peters, Erhard was skeptical of collective compulsory insurance because of his liberal approach . But he did see that society had to "draw limits or set rules through social, economic and financial policy measures".

With the concept of people's capitalism, he tried to create a freer and more equal society. Erhard justified his idea of the broad accumulation of wealth as follows: "If a concentration of the means of production is inevitable with the development of modern technology, then this process must be countered by a conscious and active will to a broad, but genuine co-ownership of that economic productive capital." Individual attempts to put the concept of people's capitalism into practice were largely ineffective. Since 1957, the social market economy has been reinterpreted from Erhard's interpretation of national capitalism to a market economy with an independent welfare state. Only then did the term social market economy become the central consensus and peace formula of the middle way (for details see section “ Setting the course for social policy ”).

Securing the value of money was also of great importance to him, in particular through an independent central bank . For Erhard, the social market economy was inconceivable without a consistent policy of price level stability . Only this policy would ensure that individual sections of the population do not enrich themselves at the expense of others. In order to guarantee the efficient use of productive capital, liability also belongs in addition to the right to private property. The owners of productive capital should not only appropriate the profits, but should also bear full liability for wrong decisions made.

When the trade unions were still calling for a comprehensive "reorganization of the economy" (Munich basic program of 1949) with the core element of economic co-determination, Erhard declared in 1949 that a clear dividing line had to be drawn: participation was an element of the free market economy, whereas co-determination was part of it Area of planned economy. Adenauer, who at that time was wrestling with the trade unions for a codetermination regulation, also demanded by the Allies, immediately took this statement as an opportunity to request Erhard by telegraph "not to comment publicly on the question of the employee's codetermination right".

In the opinion of Kurt H. Biedenkopf , the actual political development took a different direction in all respects than Erhard wanted during the reign of the Union. the restriction of the state propagated by Erhard could not be realized politically. In 1974 Ludwig Erhard declared that the era of the social market economy had long since ended and that he saw current politics as far removed from his ideas of freedom and personal responsibility.

Theoretical foundations

Conceptually, the social market economy is based u. a. to ideas that were developed by a number of scientists in the 1930s and 40s with different accentuations and subsumed under the - now ambiguous - expression neoliberalism . For Germany, the Freiburg School (see Ordoliberalism ) played a special role in this direction . The social market economy is a. based on these ideas, but at least sets different accents through greater pragmatism , for example with regard to process-political influencing of economic policy and a stronger emphasis on social policy.

Catholic social doctrine or, more generally, Christian social ethics can be seen as a further important influence on the conception of the social market economy . Their reception can be seen in particular in Müller-Armack, Röpke and Rüstow. This applies, for example, to the anthropological foundation, where the influence of Christian social teaching leads to the image of the socially bound person appearing alongside the individualistic, liberal image of man. The social market economy is indirectly influenced by the “Protestant deep grammar of ordoliberalism” ( Jähnichen ). The concept of the social market economy also included preparatory work by the Freiburg Circle , in which Erwin von Beckerath , Walter Eucken and Franz Böhm also took part in members of the Confessing Church such as Helmut Thielicke and - on occasion - Dietrich Bonhoeffer .

It is controversial to what extent Franz Oppenheimer's "liberal socialism" , with whom Erhard studied in Frankfurt and which had a strong influence on him, can be seen as a further influence on the development of the social market economy.

Walter Eucken

Walter Eucken is considered to be the most important thought leader in the social market economy . As early as 1942, Walter Eucken called for the total restructuring of the economic system. He turned against a completely free economy ( laissez-faire ) and against the so-called night watchman state , as well as against a state-controlled economy .

“[It] is a great task to give this new industrialized economy [...] a functioning and humane economic order. […] [F] inoperative and humane means: In it, the shortage of goods […] should be overcome as far as possible and continuously. And at the same time a self-responsible life should be possible in this order. "

Eucken developed the basic principles of a competitive order that guarantees efficiency and freedom through the unhindered action of the competitive process. For Eucken, the constituent principles of the competition order are a functioning price system, the primacy of currency policy, free access to the markets, private ownership of means of production, freedom of contract, the principle of liability and a constancy of economic policy. A policy geared towards this must take into account the togetherness of the constitutive principles of such a competitive order, as well as the interdependence of the economic order with other areas of life.

According to Eucken, there are areas in which the constituent principles of the competition order are not sufficient to keep the competition order functional. He names social policy, efficiency-related monopoly positions, income distribution , labor markets and environmental problems. The last four areas mentioned coincide with the regulatory principles elaborated by Eucken. However, the measures required to enforce the regulatory principles must not be implemented through a selective economic policy, but must be based on the principles of the economic constitution.

Eucken explicitly devoted a great deal of space to the social question . For Eucken there is no conflict of goals between freedom on the one hand and social security and social justice on the other, since freedom is the prerequisite for security and justice. For Eucken, correctly understood social policy is saved in a regulatory policy. Before the state takes action, politics should give individuals the opportunity to secure themselves. Efficiency-related monopoly positions are to be prevented by an independent cartel office . The distribution of income resulting from competition needs a regulatory correction for households with low incomes, for example through income taxation with a progressive rate profile . There may be a need for regulatory action on the labor market if wages fall below the subsistence level and if you are unemployed. These problems can be largely solved through optimal competition on the supply and demand side. In certain circumstances, however, minimum wages are advocated. Eucken demanded the disempowerment of the employers 'and workers' associations, which dominated the labor market and thereby restricted competition. However, unions played an important role in balancing out the inequality of the market positions of workers and employers. In environmental policy , government intervention is seen as necessary to limit external effects .

For Eucken, the most important economic and political task of the state was to prevent the concentration of economic power through monopolies, cartels and other forms of market domination. State monopoly power was just as problematic.

Wilhelm Röpke and Alexander Rustow

The advocates of sociologically shaped neoliberalism demanded that social and socio-political goals be pursued in addition to the task of guaranteeing functioning competition. According to Gero Thalemann, they saw this as an obligation of the state to intervene actively, but in conformity with the market, in the market economy.

According to Röpke and Riistow's conviction, a market economy cannot survive if it does not exist on an ethical and moral basis that the market does not create itself. Röpke names human qualities such as self-discipline, honesty, fairness and moderation. These are imparted in human society and in the family. With the formula “market economy is not everything”, Röpke warned of the threat of competition degenerating if one neglected the anthropological-sociological framework.

The concept of vital politics was developed by Alexander Rustow and Wilhelm Röpke. The core idea is that the market forces must be given a life-orientated regulatory policy. It cannot be an automatic consequence of the free market, but it is an ethical prerequisite for a legitimate market economy. In the 1960s, Müller-Armack stated that there was still a lot of catching up to do in the area of vitality politics.

Other influences

Discussion about the relationship to the Austrian school

According to Gerhard Stapelfeldt , Müller-Armack referred mainly to Walter Eucken and Friedrich August von Hayek, that is, to the neoliberalism of the Austrian school of marginal utility theory and to ordoliberalism, a variation of neoliberalism. Ingo Pies is also of the opinion that Müller-Armack was influenced by Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich August von Hayek , among many others, in the conception of the social market economy , referring to a letter from Müller-Armack. Christian Watrin writes: “Alfred Müller-Armack developed his conception using approaches that can already be found in Alexander Rustow [Free Economy - Strong State, 1933]. At the same time, his considerations include the works of the Freiburg circles [Walter Eucken, Adolf Lampe, Constantin von Dietze] […], the works of emigrants, among them especially Röpke [Die Gesellschaftskrisis der Gegenwart, 1943], the Misessche Interventionism Critique (1929), but also Hayek's The Path to Servitude (1945). ”In Knut Borchardt's view, it is precisely with regard to this open approach of the social market economy that the agreement with Friedrich August von Hayek's ideas is mostly underestimated. In a birthday eulogy, Erhard stated that "without Walter Eucken, Franz Böhm, Wilhelm Röpke, Alexander Rustow, FA von Hayek, Alfred Müller-Armack and many others who thought and argued with them", his own contribution to the foundation of the social market economy would hardly be possible would have been. The Erhard biographer Christoph Heusgen particularly praised the three main representatives of neoliberalism Hayek, Röpke and Eucken as spiritual sources of Erhard's ideas and deeds.

Kathrin Meier-Rust comes to the conclusion that the theories of the old and palaeoliberals von Mises and von Hayek are incompatible with those of the neoliberals (in the historical sense) such as Eucken, Rustow and Röpke. She refers to a letter by Rüstow to Röpke, in which the latter wrote that the old liberals “have so much to be reproached for, [we] have such a different spirit from theirs that it would be a completely wrong tactic [...] with the reputation of the To blotch insanity, obsolescence and playfulness, which is rightly attached to them. No dog will eat these yesterday's hands anymore, and rightly so. "Hayek and" his master Mises should be put in the museum in spirit as one of the last surviving specimens of that otherwise extinct class of liberals who conjured up the current catastrophe. " Sybille Tönnies also sees the incompatibility. According to Gero Thalemann, Müller-Armack's ideas are not compatible with those of Hayek, since Müller-Armack assumed that the market economy alone would not be able to guarantee social justice. Hayek, on the other hand, was of the opinion that a policy of distributive justice would destroy the rule of law . Unlike Hayek, who resolutely rejected any application of the concept of justice to evaluate concrete distribution results (e.g. the demand for a more equitable distribution of income), according to Wilga Föste, the pioneers of the social market economy explicitly referred to the concept of social justice in connection with the question of distribution , where they associated the concept primarily with the idea of commutative exchange justice. Joachim Starbatty concludes from the consensual stance towards a socio-political overload of the social market economy that the regulatory differences between Hayek and the other representatives of the social market economy were not as serious as the occasional regulatory clash of arms might lead one to believe. The differences between Hayek and the representatives of the social market economy only begin where the latter see a need for redistribution. As an example, Starbatty quotes Walter Eucken with the sentence “The inequality of incomes means that luxury products are already produced when the urgent needs of households with low incomes still require satisfaction. So here the distribution that takes place in the competitive order needs to be corrected. ”According to Reinhard Zintl, however, it was important for Hayek that the redistribution was not about correcting supposed injustices in the competitive process, but about collective responsibility. According to Zintl, the scope of what is politically considered necessary could legitimately be far above the physical subsistence level for Hayek in prosperous societies. Another difference to the ideas of the Austrian School around Mises and Hayek is that they trusted the competition of individuals as a discovery process far more than the state framework. The state played a much lesser role for them as a standard.

Hayek felt pronounced sympathy for the achievements of Ludwig Erhard in the "restoration of a free society in Germany", but was by no means on the line of the pioneers of the social market economy such as Eucken or Müller-Armack and in open dispute with Röpke and Rüstow. Martin Nonhoff , Alan O. Ebenstein, Ralf Ptak, Reinhard Zintl, Chíaki Nishiyama, Kurt R. Leube and many others quote Hayek as saying that he regretted speaking about the social market economy, although some of his friends succeeded in doing so, thanks using this language to make the kind of liberal social order he advocates appealing to wider circles. According to Martin Nonhoff, Hayek's preferred order is a spontaneous economic order, i.e. one that is as free as possible from any state control or discipline. On the other hand, Oswald von Nell-Breuning emphasized that “the commitment to the 'social market economy' always goes hand in hand with the conviction that it is possible and necessary to steer the economy,” says Martin Nonhoff. He concludes from this that “the conglomerate of possible predecessors of the conception of the social market economy” is not only full of points of friction, but also full of formidable contradictions that make the search for an actual meaning of the “social market economy” fail because of its historical origins. According to Otto Schlecht , Hayek does not deny that the state has an important role to play in every economic and social system. However, Hayek simply denied that there could be a social market economy at all, because a social market economy is not a market economy. According to Ralf Ptak , Hayek's criticism of the term “social market economy” should not be interpreted as a rejection of the ordoliberal approach, rather Hayek was concerned that this use of language could lead to an inflation of the welfare state . According to Josef Drexl, however, Hayek considered the welfare state and thus also the social market economy of German characteristics to be a mish-mash of inconsistent goals. The welfare state collides with one of Hayek's basic ideas, namely the spontaneous order according to which the result of economic activity cannot be assessed as such and therefore should not be predetermined by welfare state policy. For Ludwig Erhard, “nothing was more anti-social than the welfare state […], which relaxes human responsibility and lets individual performance decline.” According to Harald Jung, however, the conception of the social market economy (by Müller-Armack) cannot be used in any case Claim the rejection of social justice as a normative target in the sense of Hayek.

According to a personal memory by Joachim Starbatty , there was an opportunity at a colloquium in Cologne at which Müller-Armack and Hayek “arm in arm” criticized the “socio-political overload” of the social market economy, which was pursued by all parties . Starbatty concluded from the observation that the regulatory differences "between Müller-Armack, Ludwig Erhard, Walter Eucken, Alexander Rustow and Franz Böhm on the one hand, and Friedrich August von Hayek on the other hand were not as serious as the occasional din of gunfire might lead us to believe."

Friedrich Kießling and Bernhard Rieger emphasize an increasing alienation, which was also evident in the Mont Pelerin Society , where two wings were formed. The radicalizing American wing around von Hayek, von Mises and Friedman advocated an “adjective-free” market economy without state intervention . In contrast, there was the German wing, mainly represented by Rustow, Röpke and Müller-Armack, who advocated the social market economy and more active responsibility for the state as a comprehensive social, vital and social policy. These accused the American wing of betrayal of the actual goals of neoliberalism and emphasized the dangers of a morally "blunted and naked economism ".

Discussion about the relationship to socialism

The liberal socialist Franz Oppenheimer is counted among the pioneers of the social market economy. The founding fathers of the social market economy, Ludwig Erhard and Walter Eucken, were among his students. Franz Böhm and Alexander Rustow also belonged to his discussion group. Unlike Oppenheimer, Ludwig Erhard could not imagine an economy without private property. But of the values of Erhard's “social liberalism”, competition, social responsibility, the fight against cartels and monopolies, the dismantling of trade barriers, the free movement of money and capital and the idea of a united Europe (the “Europe of the free and Same ”) can be traced back to Oppenheimer's influence. According to a statement by Erhard, the accent has shifted from “liberal socialism” to “social liberalism”. Ludwig Erhard declared in a commemorative speech (1964): “Something impressed me so deeply that I cannot lose it, namely the examination of the socio-political questions of our time. He recognized "capitalism" as the principle that leads to inequality, indeed that actually establishes inequality, although nothing was further from him than a dreary leveling out. On the other hand, he hated communism because it inevitably leads to bondage. There must be a way - a third way - that means a happy synthesis, a way out. I tried, almost in accordance with his mandate, in the social market economy to try to show a not sentimental but a realistic path ”. According to Volker Hentschel, liberal socialism and the social market economy are "fundamentally different things in terms of their intellectual origins and were not communicated with one another by Erhard's economic policy concept." Bernhard Vogt sees Franz Oppenheimer as perhaps the most important thought leader in the social market economy.

According to Werner Abelshauser , in contrast to Erhard, Müller-Armack saw a meaningful connection between an active social or socialist economic policy and a market economy. Ralf Ptak sees a clear opposite position to socialism: “With the activation of the old neoliberal thesis of the unstoppable transformational character of the welfare state, the aggressive position against socialism and a renewed emphasis on regulatory principles, the social market economy was conceptually reverted to its origins by Müller-Armack Neoliberalism returned. The enemy image of socialism primarily meant democratic socialism in the form of Western European social democracy and the emerging Eurocommunism. ”Müller-Armack, who in 1947 wanted to combine“ more socialism with more freedom ”, later distinguished himself more clearly from liberal socialism. Müller-Armack was nevertheless associated with a concept of liberal socialism, similar to the ideas of Gerhard Weisser . According to the Müller-Armack biographer Rolf Kowitz, this was an assumption that was based on the ongoing discrediting of Manchester liberalism, which would not have allowed a combination of the terms “market economy” and “social” historically. These conceptual difficulties still existed in 1955, so that Müller-Armack felt compelled to clearly distinguish himself from Weisser: “The social market economy is primarily a market economy and therefore not to be confused with liberal socialism, with the primary systems of attachment with interspersed economic freedom. There are big differences. "

The concept under discussion

Hans-Rudolf Peters criticizes: “The concept of the social market economy invites, due to its extensive lack of contours and flexibility in the social part, to socio-political abuse for election opportunistic purposes and to capture votes and can thus lead to a creeping socialization, which ultimately destroys the foundations of the market economy. "Ludwig Erhard recognized" the dangers of an overflowing welfare state "early and clearly; renouncing the popular political slogan social market economy for its regulatory policy would have "certainly created more clarity".

Heinz Grossekettler is of the opinion that the expression social market economy is often understood as a market economy with a strong redistributive component. But this was not what their theoretical founders had in mind.

Ralf Ptak is of the opinion that the attacks on Müller-Armack only masked the “real strategic dilemma of German neoliberalism” in the debate on the post-war development of the social market economy. “On the one hand, the extraordinary growth period of the post-war period should be emphasized as a result of the economic policy of the social market economy, which is then interpreted as largely identical to the regulatory principles of the 'new' liberalism. On the other hand, it is necessary to condemn the factual development of the Federal Republic towards a welfare state as the beginning of the economic decline that was initiated by the inconsistent regulatory policy of a compromise-oriented social market economy ”. “The fact is, however, that both Müller-Armack's conception of the social market economy and the economic policy based on it moved precisely between these two poles”.

Friedhelm Hengsbach is of the opinion that “the radical market reference point of the conception” of the social market economy is the “ideal-typical construction of the perfect market ”. The imagination of the invisible hand , of the signaling apparatus of moving prices, of rational decisions of sovereign consumers and of markets that are freed from power under the discovery process of competition delights the reader. But it also proves that the conception of the model is not based on practical research, but on a derivation from a priori premises, i.e. is a pure construct. This makes it almost inevitable that the term social market economy degenerates into a “political battle formula”. He refers to the political initiatives of a “new social market economy”, which selectively pick out individual components of the original and historically enriched conception in order to fight against political opponents with them.

Social market economy as the economic order of the Federal Republic of Germany

General design features

Flexibility and continuity

According to Abelshauser, the social market economy is characterized by three peculiarities, despite the economic policy flexibility shown in practice, which distinguish it from the arbitrariness of rapidly changing models of economic policy.

- Far more than other economic systems, it uses the symbiosis between the market and the state to make competition functional and socially beneficial.

- It supports a strategy of productive regulatory policy. In addition to foreign trade, infrastructure policy in the broadest sense, regional development policy and a job-oriented education and training policy are a task of the state as an important immaterial production factor. At the same time, it also ensures that growing government responsibilities do not inevitably lead to increasing government spending (the share of government spending - excluding social security - has remained relatively stable between 20 and 25% since the end of the First World War).

- It is specifically tailored to the needs of the social system of production as it has developed in Germany (association coordination, co-determination, dual vocational training, etc.).

Social partnership

As a model corresponding to the social-Irish character of the social market economy, the ordoliberals, as well as Christian social doctrine, saw the idea of social partnership in the 1950s , which was later implemented in various legal works. It is now considered an essential element of the social market economy.

Ludwig Erhard, on the other hand, repeatedly criticized the “so-called social partners” who struggled for the distribution of the national product, which he saw threatened the common good. According to Tim Schanetzky, this shows Erhard's exaggeration of the state as the guardian of the common good and its distrust of “group egoisms”.

The regulations on collective bargaining autonomy and company co-determination that existed in the Weimar Republic were repealed by the National Socialists in 1933. The administration of the bizone had already restored collective bargaining autonomy with the collective bargaining act . This regulation was adopted by the Adenauer government. In his government declaration of September 20, 1949, Konrad Adenauer made it clear that in order to achieve the social market economy, a contemporary reorganization of the legal relationships between employers and employees would have to be achieved. Another element of the social partnership was the Works Constitution Act of October 11, 1952, which regulated the co-determination of employee representatives in personal, economic and social matters. In the 1970s, the social-liberal government adopted even more extensive regulations to humanize work processes with the amendment of the Works Constitution Act of 1972 and the Codetermination Act of 1976.

The trade unions initially tried to combat the social market economy in the founding phase and sought a different economic order. In the practice of the social market economy, however, it has been possible to involve the trade unions in the economic-political processes precisely through the possibilities of co-determination. Conversely, the trade unions in the social partnership have helped shape the social market economy. Continued payment of wages in the event of illness, social plans, extended participation rights and minimum wages are among the social achievements that contributed to the general popularity of the social market economy.

In an article for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , the labor lawyer and publicist Bernd Rüthers sums up : “My thesis: the social market economy and social partnership belong together. One is a necessary basis for the other. ” Karl-Heinz Paqué considers collective bargaining autonomy and the welfare state to be“ constitutive elements ”and“ pillars of the social market economy ”. According to Birger Priddat , co-determination as a core element of the social partnership binds the partners to the purpose of the cooperation: "Maintaining a social market economy".

The President of the Confederation of German Employers' Associations , Ingo Kramer, said on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the Codetermination Act of 1976: "Codetermination is an expression of the German understanding of social partnership within the framework of the social market economy, which is a foundation of our social system."

Germany AG

The Germany AG was based on the organizational structure of the double joint stock companies whose operational management is governed by the Board, Policy and important personnel decisions but like the board. This double structure enabled strategic networks, institutionalized communicative networks of leading players from business, politics and science who are closely connected in corporate management. Since bank representatives on the supervisory board were able to better control the company, on the other hand, long-term stability of the financing by a house bank or by the shareholders represented by the bank is ensured. As a result, investors until the end of the 1980s were less oriented towards the principle of short-term shareholder value , but rather behaved like shareholders in a family company , whose investment motive is not short-term earnings, but rather the optimization of long-term profit by increasing the value of "their" company. As a result, large-scale industry in West Germany was given a perspective geared more towards long-term sustainability until the early 1990s.

Further design features

General design features of the social market economy as the economic order of the Federal Republic of Germany are above all the free price formation for goods and services, the pursuit of profit as a performance incentive, an independent central bank , collective bargaining , an active state economic, economic, tax and educational policy and a social network that protects against economic hardship when self-sufficiency is not possible.

State economic policy is carried out on the one hand through regulatory policy and on the other hand through process policy . The regulatory policy aims to set a legal and institutional framework for market processes and to correct market deficiencies . The process policy aims at a stability policy in the sense of the magic square and a correction of the income and wealth distribution as well as the distribution of opportunities in Germany via tax rates and socially differentiated state benefits as well as labor and social legislation.

development

prehistory

In the immediate post-war period, public service approaches were quite popular among the population . However, hesitant approaches were blocked by the USA. Socialist rhetoric also shaped the party programs of the SPD, which strived for "liberal socialism", and the CDU, which propagated "Christian socialism". In retrospect, the impression arose that in the post-war period the free market economy was opposed to the central administration economy. In fact, the positions of the experts and political parties were closer together. Laissez-faire liberalism had been completely discredited since the Great Depression (1929) . However, approaches that are skeptical of the market economy have hardly played a role since the global economic crisis was overcome. As early as the mid-1930s, the regulatory alternative in Germany had narrowed to the alternatives between a “controlled market economy” of reform-liberal origin and the “market-based management economy” of the Keynesian type . The social market economy is by no means a spontaneous idea of the post-war period, but the result of a social learning process that was initiated by the global economic crisis of the 1930s.

Phase of dominance of ordoliberalism (1948–1966)

Setting the course for economic policy

In the time of need after the Second World War, the management system , which had its origins in the war economy, was continued almost unchanged. Planning and steering the economy were then used as a makeshift solution in order to get economic life going again in the first place. In the "era of 1000 calories" (actually: 1000 kcal), nutrition policy control was literally essential for survival for large parts of the population. As Bavarian Minister of Economic Affairs, Ludwig Erhard wrote that the regulation of management and price monitoring could not be dispensed with as long as the disparity between disposable purchasing power and consumption-ready national product persisted.

Unlike the housing infrastructure, Germany's industrial fabric was not significantly destroyed by the Second World War and the reparations. The gross fixed assets had fallen to the level of 1936 by 1948, although the majority of these were relatively new, less than 10 years old systems. Industrial production, however, only reached less than half of the 1936 value. In 1947, measures were taken in the American and British occupation zones to restore the war-torn transport infrastructure. Production rose from autumn 1947 onwards, but the population's supply situation did not improve, as large quantities of stock were produced in anticipation of a currency reform. As director of the two-zone economic council, Erhard ordered a staggered release of prices on June 20, 1948 in direct connection with the currency reform by the Allies . According to the “guiding principle law” drawn up by the ordoliberal Leonhard Miksch , first the prices for consumer goods and later the prices for industrial goods, heating and food were released. Shortly after monetary union, the shop windows were suddenly full, as the hoarded goods could now be exchanged for stable money. This amazed contemporaries so much that many saw the monetary union as the real spark for the economic miracle . In fact, the currency reform was necessary, but it should be put into perspective that the dynamic economic upswing actually began in 1947 (from January 1947 to July 1948, industrial production rose from 34% to 57% from the level of 1936, from the currency reform to the founding industrial production rose to 86% in the Federal Republic). When the prices were released, the so-called breakthrough crisis arose. The cost of living rose faster than hourly wages and unemployment rose from 3.2% in early 1950 to 12.2%. The social component of the social market economy at this time consisted essentially of the already existing system of social insurance, which, according to Henry C. Wallich, made the situation “just about socially acceptable”. The situation on the labor market eased in the wake of the global economic boom following the Korean War. However, the Allied High Commission demanded that Germany make its contribution to Western defense readiness by preferentially expanding the free steel production capacities. This embarrassed Ludwig Erhard, who had meanwhile dismantled the planning staff in the Federal Ministry of Economics. In this situation, the central business associations and the trade unions took the initiative and (in agreement with the Federal Minister of Economics) formed a purchasing cartel that steered raw materials away from the consumer goods industry and towards heavy industry. In this way they filled the steering loophole that Erhard's economic policy had deliberately left and strengthened their influence considerably. This fundamentally changed the framework conditions for the social market economy; the Korean crisis accelerated the renaissance of the corporate market economy.

After the establishment of the Federal Republic of Germany, further important regulatory decisions were made. So z. B. the anchoring of collective bargaining autonomy through the Collective Bargaining Act of 1949 and the regulation of company co-determination (in social and personal questions) and participation (in economic questions) of employees through the Works Constitution Act (1952). The trade union conception for the reorganization of the economy with its core element of economic co-determination and the ordoliberal conception of the social market economy were diametrically opposed in the first decade of the Federal Republic. The Bundesbank Act of 1957 gave the Deutsche Bundesbank price level stability as its most important goal. However, participation in the Bretton Woods system from 1949 to 1973 meant that the Deutsche Bundesbank often had to buy foreign currency to support the fixed exchange rates , which increased the money supply and thus inflation, but at the same time led to an undervaluation of the DM and thus to it favorable export conditions. Price level stability only had a real priority from 1973 onwards. The chronic undervaluation of the D-Mark up until 1973 contributed greatly to the rise of the German automotive industry.

The creation of perfect competition by fighting market power was a central concern of the ordoliberals, which Miksch also represented in the Federal Ministry of Economics. However, the resistance of German industry to the first drafts of competition law was rigorous and successful. It was not only borne by the self-interest of the corporations, but also by the real danger that the radical suppression of the economic concentration process through a strict competition policy would have endangered the international competitiveness of German industry compared to large foreign corporations due to the economies of scale . The “naive” idea of the ordoliberal economic utopia of a market economy made up of small and medium-sized enterprises was seen as a threat to the German export economy and the economic recovery as a whole. In 1958 the law against restraints of competition was finally passed and the Federal Cartel Office was founded to serve the model of free competition. Cartels were banned in principle, but exceptions were made for conditions, discounts, foreign, structural crisis, export and rationalization cartels. However, this was far from ordoliberal ideas. Franz Böhm publicly acknowledged the defeat in what, according to ordoliberal ideas, should have become the core element of the German economic order. In 1949, Miksch told Walter Eucken : “We now have to seriously consider moving away from the current government course. The Adenauer cabinet turns out to be more and more of an interest government. Agricultural and heavy industrial influences have combined. We can no longer watch. It will be said later that it was our ideas. "

Setting the course for social policy

In the early days of the social market economy, the existing social safety net continued to exist, which essentially consisted of the system of German social insurance that had been founded by Bismarck in the 1880s and since then has been expanded in various ways. With a social benefit quota of 15%, Germany belonged to the top group of European countries. The decision on how to shape the social dimension of the social market economy was initiated on the question of pension reform. The funded statutory pension insurance had largely been devalued by hyperinflation and silent war financing . In order to secure the livelihood of the pensioners, the pension insurance had to be put on a new basis. People's capitalism, the conversion to a welfare state based on the British-Scandinavian model and the more efficient design of the Bismarck social insurance towards a modern welfare state were up for discussion.

According to Erhard, a properly ordered market economy should promise prosperity for everyone . With what is known as popular capitalism , broad wealth accumulation should be promoted. His goal was the utopia of a depoletarianized society of property citizens who no longer need social security. After Lutz Leisering and Werner Abelshauser, Erhard developed the concept of people's capitalism as a counter-concept to the Bismarckian welfare state . However, according to Hans Günter Hockerts , the fact that Erhard did not fundamentally reject the pension reform in the cabinet deliberations speaks against this view . Although he rejected the link between the pension and the development of collective wages, he was in favor of a significant increase in the pension level and the alignment of the pension with the development of productivity. Marc Hansmann, on the other hand, sees "bitter resistance" that Erhard put up against the pension reform. According to Michael Gehler , Erhard preferred mandatory private insurance. Efforts to build wealth on a broad basis, e.g. B. through "people's shares", however, were not able to advance popular capitalism in practice. In 1974 Willy Brandt remarked “that the“ people's capitalism ”that Ludwig Erhard raved about was a dream; the "people's share" will not be noted in social history as a successful experiment. "

The insight into the inadequacy of the distribution of income and wealth resulting from the market mechanism spoke against popular capitalism. The trend towards an unequal distribution of income and wealth was palpable as early as the 1950s. Despite the rhetoric of wealth policy, the claims from statutory pension insurance remained more important than any other source of income for employees' old-age provision, and the volume of statutory pension insurance by far exceeded the volume of wealth accumulation by private households. The high conversion costs spoke against the conversion to a welfare state in the Beveridge system . The pension reform of 1957 showed that the German Bismarckian social insurance tradition had prevailed both against more comprehensive Beveridge systems based on the principle of citizenship and against Ludwig Erhard's shrunken version of welfare state intervention. As a result of the pension reform, the old-age pension was no longer regarded as an allowance for maintenance, but as a replacement for wages. The standard pension should now comprise 60% of the current average wage of all insured persons (in 1956 it was only 34.5%). Like no other event, the pension reform has restored the confidence of the German citizens in the welfare state and permanently strengthened social peace. The formula social market economy has been reinterpreted since 1957 from Erhard's interpretation of national capitalism to a market economy with an independent welfare state. Only then did the term social market economy become the central consensus and peace formula of the middle way.

Economic miracle

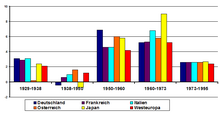

The period between the end of the Second World War and the first oil crisis was characterized by high economic growth rates and high income increases ( post-war boom ). At the same time, the income levels of the Western European countries and the USA became more similar. Unemployment fell, there was relative price stability and employee incomes rose. The message “Prosperity for all” given by Erhard as a goal seemed achievable in the foreseeable future. However , Erhard himself rejected the much-cited expression " economic miracle ". In Germany, the post-war boom was for a long time viewed as a specifically German development and the reasons for the boom were therefore only sought in German economic policy. In the 1970s, a connection to the war damage was established (reconstruction thesis). In the late 1970s, economic historians discovered that an outstanding post-war boom had occurred across Western Europe and Japan. The thesis was put forward that the economies that had the relatively lowest productivity after 1945 produced the highest productivity gains and the highest economic growth until the 1970s (catch-up thesis). The interpretation of the post-war boom is still not entirely uniform among economic historians and economists. However, the view has largely gained acceptance that the reconstruction effect played a major role until the end of the 1950s and the catch-up effect until the beginning of the 1970s.

Herbert Giersch , Karl-Heinz Paqué and Holger Schmieding explain the German post-war boom with the ordoliberal regulatory policy. The upswing was initiated by a market economy shock therapy as part of the currency reform. A cautious monetary and fiscal policy led to persistent current account surpluses. The growth of the 1950s was driven by the spontaneous market forces of a deregulated economy and ample corporate profits. Increasing regulation, higher taxes and rising costs would then have slowed growth from the 1960s onwards. Against this point of view, for example Werner Abelshauser or Mark Spoerer object that a West German special development is postulated, but does not correspond to the facts. There was not only a German economic miracle, but also z. B. a French. French economic growth in the 1950s to 1970s was almost parallel to that in Germany, although the social market economy in Germany and the more interventionist planification in France represented the strongest economic and political contradictions in Western Europe. This suggests that the various economic policy concepts have little practical importance as long as property rights and a minimum of competition are guaranteed. According to Thomas Bittner , French economic policy did not follow a closed concept. The policy recommendations of the concept of the social market economy are also imprecise, so that a theoretically well-founded overall regulatory concept is missing in both countries. According to Bittner, due to considerable research gaps, it is still not possible to assess whether and to what extent the conceptions of the social market economy on the one hand and planification on the other hand contributed to the high economic growth of the post-war period in Western Europe.

The reconstruction thesis was developed in rejection of a specifically German interpretation. According to the explanatory approach developed in the 1970s by Franz Jánossy , Werner Abelshauser and Knut Borchardt in particular , productivity growth remained far below the potential production potential of the German and European economies due to the effects of the First and Second World Wars and the intervening global economic crisis. Abelshauser was able to show, following contemporary work, that the extent to which German industry was destroyed in the war had been greatly overestimated in literature. While the Allies had succeeded in destroying entire cities, the targeted destruction of industrial facilities had hardly succeeded. In spite of all the destruction, there was therefore a significant amount of intact capital stock, highly qualified human capital, and tried and tested corporate organization methods. Therefore, after the end of the war, there was particularly high potential for growth. Due to the falling marginal return on capital, the growth effect of investments was particularly high at the beginning of the reconstruction and then declined as the economy approached the long-term growth trend. The Marshall Plan is not considered to be of great importance for the West German reconstruction, since the aid started too late and had only a small volume compared to the total investment. A “mythical exaggeration” of the currency reform is also rejected. The reconstruction process began a year before the currency reform with a strong expansion of production, which was the decisive prerequisite for the success of the currency reform. A comparison of economic growth rates reveals that countries that had suffered considerable war damage and a tough occupation regime recorded particularly high growth rates after the Second World War. In addition to Germany, Austria, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands and France experienced rapid catch-up growth of (on average) 7–9% annually between 1945 and 1960. Countries less severely affected by the war or neutral countries experienced economic growth of “only” 3–4%. According to Ludger Lindlar, the reconstruction thesis therefore offers an explanation for the above-average growth rates of the 1950s. But only the catch-up thesis can explain the high growth in the 1960s.

The catch- up thesis put forward by economic historians Angus Maddison and Moses Abramovitz in 1979 is represented today by numerous economists (including William J. Baumol , Alexander Gerschenkron , Robert J. Barro and Gottfried Bombach ). The catch-up thesis indicates that by 1950 the USA had achieved a clear productivity lead over the European economies. After the war, the European economy started a catch- up process and benefited from the catch-up effect . European companies were able to follow the example of American companies. Figuratively speaking, the catching-up process took place in the slipstream of the leading USA and thus allowed a higher pace. After the productivity level of the American economy had been reached and the catching-up process had come to an end, the Western European economy stepped out of the slipstream at the beginning of the 1970s, so that growth rates as high as in the 1950s and 60s were no longer possible. The catch-up thesis can be the different high growth rates z. B. between the USA and Great Britain on the one hand and Germany or France on the other. According to an analysis by Steven Broadberry , z. For example, Germany has a strong productivity growth potential by reducing low-productive sectors such as agriculture in favor of high-productivity sectors such as industrial production. There was no such potential for the more industrialized Great Britain. While only 5% of the working population in Great Britain worked in the agricultural sector in 1950, it was 24% in Germany. According to an econometric analysis by Ludger Lindlar, the catch-up thesis for the period from 1950 to 1973 offers a conclusive and empirically well-supported explanation for the rapid productivity growth in Western Europe and Japan.

End of the ordoliberal phase

In 1954, Ludwig Erhard remarked to Chancellor Adenauer that it was becoming increasingly difficult to brand the political opponent SPD as a planned economy party, since their economic criticism concentrated almost entirely on the lack of economic security. However, he was convinced that an economic policy based on the economic theory of ordoliberalism would be able to overcome economic cycles. But even among Ludwig Erhard's partisans, there was some criticism of the abstinence in planning and economic policy. Alfred Müller-Armack had called for a second phase of the social market economy in which economic policy should play a certain role.

In the mid-1960s there were increasing signs that the boom during the reconstruction phase was coming to an end. The growth rates were still relatively high, but in retrospect it was clear that the growth had decreased from cycle to cycle. At the end of 1966, the Federal Republic was confronted with its first slight recession, which, however, hit the “economic miracle” completely unprepared. Erhard was criticized for the first time not only by the opposition, but also by the business press and the Advisory Council for the first time because of his economic policy. The crisis had far more serious political than economic consequences, it led to the end of the Erhard era.

Global control phase (1967–1982)

The second phase of the social market economy began in the mid-1960s, in which economic and socio-political ideas of democratic socialism shaped the design of this economic order. This design was also associated with the concept of the social market economy in public opinion.

The Stability Act of 1967, which resulted in a change of course towards an active economic policy , was of great importance . The then Minister of Economics, Karl Schiller, described it as the “procedural constitution”, which supplements the “regulatory constitution” of the Cartel Act. He saw this as a “symbiosis of the Freiburg imperative and the Keynesian message”. In practice, the post-Keynesian concept of global control should permanently dampen economic fluctuations. The concept was initially extremely successful in terms of employment policy. Full employment was restored and maintained until the mid-1970s. However, the problem of monetary stability came to the fore. The oil crises of the 1970s increased price pressures from imported inflation. Economic growth has also cooled down worldwide since the 1970s. This made fine-tuning the economy more and more difficult. The concept of wanting to completely smooth out economic fluctuations is now largely regarded as outdated. According to the majority view, economic policy in the form of post-Keynesian fiscal policy is still necessary in the "Keynesian situation" of a more severe economic crisis (such as the financial and economic crisis since 2007 ), since monetarist monetary policy and automatic stabilizers reach their limits in the liquidity trap situation . The economic policy objective set by the Stability Act, to observe the requirements of economic equilibrium and to align economic policy with the magic square, has remained permanent .

The Co-Determination Act of 1976 introduced an extended co-determination compared to the Works Constitution Act of 1952. In companies and groups with more than 2000 employees, the supervisory board has since been made up of equal numbers of representatives from the shareholders and employees. In the event of a tie in votes, however, the vote of the chairman of the supervisory board (provided by the employer) is decisive. The Codetermination Act should serve to humanize the world of work, in that not only the interests of the shareholders but also the interests of the employees are heard. Right from the start, codetermination in Germany aimed to reduce transaction costs . In-house transaction costs are lower, the more pronounced the possibility of trusting cooperation is, while on the other hand the transaction costs are higher, the more cooperation is only possible with the help of formal rules and coercive measures. Long-term stable and low-conflict working relationships enable companies to invest in the training and further qualification of their employees on a long-term basis. This is one of the prerequisites for entrepreneurial success, especially under the conditions of the rapid increase in intangible value creation in the post-industrial society or the knowledge society , because intangible value creation is based i. d. Usually on specific knowledge that is not easy to replace and the productive implementation of which is not easy to control. At the same time, companies have a greater incentive to make cost-intensive investments, which is strengthening Germany as a location, especially in times of structural change. Precisely because of the continuous advancement of the division of labor and immaterial production, which fundamentally increase transaction costs, the co-determination institution has also been able to thrive in practice. According to Jürgen Schrempp , codetermination is part of the German model that prevents short-term profit maximization at the expense of necessary investments in the future.

In social policy there was a further expansion of the welfare state. The pension reform of 1972 extended insurance coverage to larger parts of the population such as the self-employed, students, housewives, farmers and the disabled. Critics saw this as a further decoupling of the contributions from the benefits and, in general, a dilution of the insurance character.

Phase of dominance of regulatory policy and offer orientation (1983–1989)

The turning point of 1982/83 had the goal of ending the demand policy of the 1960s and 70s and moving to a supply policy that was supposed to restore full employment. She followed the international trend ( Reagonomics , Thatcherism and the “politique de rigueur” by François Mitterrand ). The Deutsche Bundesbank and later the European Central Bank pursued a restrictive interpretation of monetarist monetary policy more decisively and for longer than other central banks, but the restrictive monetary policy was nowhere successful. In practice, the federal government pursued a policy mix that still included a certain control of economic development through fiscal policy. The intended cut in subsidies remained rhetoric, and social spending continued to expand after initial cuts. Tax cuts reduced the tax burden by a total of DM 63 billion , but had no significant impact on investment and economic growth. Unemployment has fallen somewhat in the wake of the global economic recovery since 1983, but then rose to new record levels in the 1990s. The growing unemployment trend observed since the 1970s remained unbroken.

German Unity (1990)

The social market economy was defined in the Treaty on Monetary, Economic and Social Union of May 18, 1990 as the common economic order of reunified Germany. It was determined in the State Treaty in particular by private property, performance competition, free price formation and, in principle, full freedom of movement for labor, capital, goods and services (Article 1 paragraph 3).