Arkansas Traveler

The Arkansas Traveler or Arkansas Traveler , sometimes also Arkansaw Traveler , is a figure of American folklore and popular culture that emerged in the first half of the 19th century . The story of a well-dressed traveler on horseback, the Arkansas Traveler , who asks a settler playing the fiddle to sleep in his shabby hut, exists in numerous variations . The settler initially rejects him, referring to the cramped conditions and his poverty, and tries in vain to play a full melody on the fiddle. The traveler has the fiddle and plays the whole melody, whereupon the settler enthusiastically offers him board and lodging.

The first version of the humorous story of the Arkansas Traveler is said to come from " Colonel " Sandford "Sandy" Faulkner (1806–1874), a plantation owner and politician from Little Rock. In addition to his story, Faulkner composed the melody The Arkansas Traveler around the middle of the 19th century , which has since been underlaid with various texts. Two entertainers, Joseph Tasso from Cincinnati and Mose Case , are identified by other sources as the authors of dialogue and melody, while others attribute both creations to intangible authors of the early 19th century. A variant of the Arkansas Traveler was the State Song from 1949 to 1963 and has been the State Historical Song of the state of Arkansas since 1987 . The Arkansas Traveler was frequently performed on the vaudeville stages , and by the turn of the century numerous recordings of skits were made on phonograph cylinders and records .

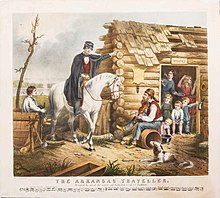

Around 1856 Edward Payson Washbourne (1831-1860) painted his painting The Arkansas Traveler , with the mounted traveler and the settler seated in front of his hut. Engraving and lithograph reproductions of this painting were sold in large numbers throughout the United States in 1859 and 1870 . The Arkansas Traveler also became known through these prints and their imitations on the covers of song collections and scores.

The couple of the Arkansas Traveler and his partner, the poor, child-rich, always drunk and stupid Hillbilly of the Ozarks , was at times viewed as a discriminatory stereotype and heavily criticized. The Arkansas Traveler always remained a positively perceived symbol of the state of Arkansas and became the namesake of newspapers, radio and television shows, a baseball team, a tomato and peach variety and an honorary title awarded by the governor.

The Arkansas Traveler Stories

A transcript of the dialogue between the Arkansas Traveler and the Settler, as it was popular at the turn of the century, is printed as an appendix to the autobiography of William F. Pope (1814–1895). Pope, who got to know Sandford Faulkner himself, gives the story of how it came about as follows:

"Colonel" Sandford C. Faulkner, a wealthy plantation owner from Chicot County , Arkansas, got lost one day in the Bayou Macon area and finally came across the ramshackle hut of a poor settler. There the conversation took place between Faulkner and the settler, who did not repair the holey roof of his hut because it was raining, and who did not repair it when the weather was fine because it did not rain in then. All Faulkner's questions about food, drink and a place for the night were rejected and, moreover, Faulkner received little meaningful answers to his questions: Where does this street go? - I don't know. When I get up in the morning, she's always here. - I just saw a horse with a broken leg. Aren't you killing horses with a broken leg here? - no We kill them with a gun.

During the conversation the settler tries to play a melody on his fiddle, but only brings out the first half. Faulkner can be given the fiddle and plays both parts, with which he inspires the settlers. He offers Faulkner the only dry place in the hut, food for his horse and plenty of his hidden whiskey.

Another variant takes place in the time before the gubernatorial elections in 1840. The later election winner Archibald Yell , the Senators William Savin Fulton and Ambrose Hundley Sevier , the later Senator Chester Ashley and "Colonel" Faulkner were on a campaign trip and had in the Boston Mountains , part of the Ozark Plateau , lost the way. At a settler's hut, Faulkner, spokesman for the tour company, asked for directions, and his companions were amused by the dialogue that followed. At the governor's inauguration ceremony and on numerous occasions until his death in 1874, Faulkner was asked to replay his conversation with the settler. He did this in the form of a dialogue in which he took on both roles and contrasted the cultured traveler with the settler who answered with a broad dialect. In his humorous rendering of the conversation, Faulkner soon included playing the fiddle, which helps the traveler gain the settler's trust and support.

In addition to "Colonel" Faulkner, the violinist, composer and orchestra director Joseph Tasso (1802–1887), who was born in Mexico to Italian parents and lives in Cincinnati , Ohio , is named as the originator of the dialogue. Tasso's real name was Marie de los Angelos José Tosso and had received his musical training at the Paris Conservatory . He is said to have presented the Arkansas Traveler as early as 1841 or 1842 in Cincinnati as a dialogue with the melody as an accompaniment and described himself as the originator of dialogue and melody. Other sources also state that the story was known in Ohio and was performed frequently, but without naming an author. The third possible author is Mose Case (around 1824-1885), an albino Afro-American entertainer from Charlestown , Indiana , who was also active as a composer and arranger . Case published several scores with accompanying dialogue text in the mid-1860s, which almost always cited him as the author of the melody and text.

Mary D. Hudgins (1901–1987), a connoisseur of the music and folklore of Arkansas, assigns all three alleged authors only the role of arranger. Both the dialogue and the melody are much older. Hudgins gives specific dates for this. The Arkansas Traveler is said to have been played at a wedding reception in Columbus , Wisconsin in 1845 . The mid-19th century magazine Spirit of the Times named the Arkansas Traveler a popular dance tune in Hot Springs , Arkansas . A dialogue-based sketch was performed in Salem , Ohio in 1852 . Long before 1855, the boatmen on the Mississippi were said to have known both the dialogue and the melody. A famous racehorse around 1840 was called the Arkansas Traveler . Hudgins thought it unlikely that Faulkner, Tasso, and Case knew each other. Due to the clear differences in the dialogues and the melodies, she assumes that all three have drawn independently of one another from an already existing source. The examples given and dated by Hudgins are not supported by sources and could only safely exclude Mose Case, born around 1824, as the author.

The story of the Arkansas Traveler was only noticed by the educated elite of the cities as an occasional performance by prominent members of society or representatives of upscale entertainment, partly because of its coarse humor. But it quickly gained great popularity among the rural population. By the mid-19th century, it was popular as a narrative and song text in Old Southwest and the Ohio Valley . As a sketch by a solo entertainer or two actors, it was performed many times in sideshow , US vaudeville , in circuses and in restaurants in the second half of the 19th century . With the invention and spread of phonographs and gramophones , it became more widespread, and a number of entertainers published the performance on phonograms.

Around the common core of the educated and wealthy traveler and the simple-minded poor settler, who are connected by their play on the fiddle, there are numerous variants that often correspond to the individual preferences of the narrator or the audience. In one story the question of the traveler whether there are Presbyterians in the area is answered , one of the woman of the house hangs up on the wall, my husband pulls everything he shoots off the skin . The juxtaposition of two protagonists with very different socio-economic status is typical of the humorous literature of the old American Southwest. The genre had its roots in the rapid and profound changes to which the population of the Wild West was subjected. In their endeavors to document the peculiarities of their homeland and their culture, the writers often created caricatures that had little reference to reality. In addition, the dialogue caricatures the division of the Arkansas Territory and the young state into an economically successful population of the lowlands with its cities and cotton plantations and the economically weak population of the mountains with their small farms.

In 1866, the American playwright Edward Spencer wrote the drama Down on the Mississippi for the popular New York actor Frank Chanfrau . The life of the protagonist Jefferson turns upside down when a stranger kidnaps his wife and daughter. After many years of searching, the wealthy Jefferson finds his daughter again and is able to defeat the stranger. Chanfrau's manager Thomas B. de Walden changed the piece by adding the story of the Arkansas Traveler as a prologue and changing the title to Kit, the Arkansas Traveler . The Settler Kit Redding became the title hero and traveler, while the original Traveler became the villain. After an initial failure, the play became extremely successful and saw countless performances in front of full houses from 1870 to the turn of the century, after Chanfrau's death in 1884, his son Henry Chanfrau took the title role. For the American genre of Border drama is Kit, the Arkansas Traveler one of the most important representatives. The material was filmed under the same title in 1914.

The Arkansas Traveler as melody and song

The melody of the Arkansas Traveler is said to be traced back to "Colonel" Faulkner, Mose Case or Joseph Tasso . The melody was first published in print in 1847 as The Arkansas Traveler and Rackinsack Waltz in an arrangement by William Cumming by publishers Peters and Webster in Louisville , Kentucky and Peters and Field in Cincinnati , Ohio . In 1851 it was called A Western Refrain , but later releases again called the tune The Arkansas Traveler . This was followed by numerous other arrangements, including one in 1930 from the music publisher G. Schirmer, Inc. published orchestration and jazz adaptations. The Arkansas Traveler is one of the most frequently listed and published tunes in American folklore.

The first printed rendition of the melody with accompanying dialogue was published between 1858 and 1863 by Mose Case, a composer and arranger popular at the time . In 1863, the same version was included in Mose Case's songbook War Songster . In December 1863 an edition was published by Oliver Ditson & Co. in Boston, in which Mose Case was named as the author. All of these editions had very little circulation. It was not until the Arkansas Traveler's Song Book , published by Dick & Fitzgerald in New York City in 1864 , in which the first five pages were taken up by Mose Case's song, that the Arkansas Traveler gained national fame. At the time, Dick & Fitzgerald published a large number of songs from the Minstrel Shows , which were sent postage free for ten cents to anywhere in the United States and contributed greatly to the spread of stereotypes, mostly racist content. Dialog, which is now available in print, was also distorted beyond recognition compared to Faulkner's version and the painting made a few years earlier. In particular, the connecting element, the common origin of the settler, traveler and narrator or painter from Arkansas, and the commonality of the actors found in playing on the fiddle, were largely lost. In the extreme, the settler was stupid and malicious and the traveler a visitor from the east who never ventured back to Arkansas.

One of the interpreters was Len Spencer , who recorded the Arkansas Traveler several times alone or with changing partners for various record producers. The publications took place between 1901 and 1919. Other interpreters were 1922 Steve Porter and Ernest Hare and 1925 Gene Austin and George Reneau as The Blue Ridge Duo with a square dance version for the Edison Record Company. A version recorded in 1922 by Eck Robertson and Henry Gilliland was one of the first 50 audio documents recorded in the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress in 2002. In 1949 the old melody and a newly written text were named State Song after Eva Mare Barnett's Arkansas song had to be replaced due to a dispute over copyright. In 1963 the disputes were resolved and Arkansas became State Song again. In 1987 it was replaced by two new songs for the 150th anniversary of the state, Arkansas became State Anthem and The Arkansas Traveler became State Historical Song.

The popular Arkansas Traveler melody is said to have been brought back to Ireland by tramps and sailors in the mid-19th century, where it was popularized as the Reel Soldier’s Joy or the ballad The Wind That Shakes the Barley . In fact, the similarity of the Arkansas Traveler is likely to be due to the fact that the composer, be it Faulkner or someone else, modified the motifs of existing Scottish and Irish folk songs.

The Arkansas Traveler in the picture

Edward Washington's painting (around 1856)

Around 1856 Edward Washbourne painted his painting The Arkansas Traveler , with which he set the story of the Arkansas Traveler in the picture. In a letter from Washington to his brother from June or July 1856, he mentions the Arkansas Traveler and states that he would like to have the picture, which was apparently already finished at that time, engraved. This only happened years later, shortly before Washington's death. In its March 31, 1860 issue, the Little Rock- published True Democrat named in an obituary for Washbourne The Arkansas Traveler a true picture from the south, by an artist from the south . A second painting by Washington, The Turn of the Tune , to which he was inspired by the great success of the Arkansas Traveler , he could no longer complete. It was on his easel at the time of his death and shows a continuation of the Arkansas Traveler , now the Traveler plays on the fiddle and the settler dances to it.

There is a series of clues as to the whereabouts of the two originals, mainly family correspondence from the Washbournes. In 1860, Edward's brother Henry wrote a letter describing the home of Cephas Washburn in Norristown . The house of the father, who died nine days before his son, was adorned with paintings by Edward draped in black crepe as a sign of mourning . The Arkansas Traveler was one of them, and the family's intention was to have the painting done again and thus ensure the old age of the widow Washburn. Oral tradition in the Washbourne family indicates that contracts for engraving and reproduction were signed in late 1860 or early 1861, but never a cent went to the family. The paintings - including the unfinished second - were sent to New York City and were lost during the Civil War of 1861-1865. In 1866, Edward's brother, Woodward Washbourne, went to Washington, DC for Indian mission affairs and tried in vain to locate the paintings on the east coast.

The Arkansas History Commission received a donation of several Washington paintings from descendants of the family in 1957. There was also a poorly restored version of the Arkansas Traveler , which is said to be the original that was believed to be lost. However, it is also believed that this painting is a copy made by Washbourne himself and left by his mother, or a copy by someone else's hand. The thesis of the foreign copyist is supported by the clear discrepancies between the painting and the first engraving, published during Washington's lifetime. A clear indication that the surviving painting in the possession of the Arkansas History Commission could not have been the model for Grozelier's engraving is the poor and distorted execution of the saddle notches on the corners of the log house, which are perfectly superimposed on the engravings lie. Washbourne, as a resident of the West, would not have painted such an inadequate rendering of a log cabin, and his artistic training enabled him to do more than the in many ways primitive style of the painting. Grozelier, on the other hand, as an engraver, was obliged to reproduce the original exactly and he barely had the ability to recognize Washington's painting as faulty and to correct the errors properly.

The art market often offers paintings with the motif of the Arkansas Traveler , some of which date from the 19th century, but are merely more or less successful copies of Washington's work. They were often painted clearly recognizable from the lithographs. Of note among the copies is a work by the painter James M. Fortenberry, which was shown as a contribution by the state of Arkansas to the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia . The painting was based on Grozelier's lithograph, which is now owned by the Arkansas Historical Society.

In the second half of the 19th century, the theme of the Arkansas Traveler was repeated and reproduced more or less modified on the covers of songbooks and scores. A sheet of music by Mose Case published around 1863 shows an Arkansas Traveler on the cover who is on foot. In 1864 Dick & Fitzgerald published the Arkansas Traveler's Song Book , the title song of which sings about a wandering Arkansas Traveler , while various motifs from Washbourn's paintings are used on the title: the raccoon skin on the hut, the empty whiskey barrel as a seat for the fiddler and the mounted traveler are obviously from Washbourne and have been modified to the extent that its copyright was preserved.

Engraving by Leopold Grozelier (1859)

As an engraving, Washington's painting was first published in 1859 by JH Bufford and Sons in Boston. Washbourne had traveled to Boston to contact the French-born lithographer Leopold Grozelier (1830-1865), who worked for Bufford and Sons. The lithograph included a dedication to Sandford Faulkner and, as part of the caption, a staff with the melody but without dialogue or lyrics. It is noticeable that the “WHISKEY” sign above the door of the hut has a mirror-inverted “S”, as is also shown on Washbourne's alleged original, and that the engraving is similar in its proportions to the painting. The rest of the representation is much finer than that of the alleged original and also more similar to the later lithographs by Currier and Ives. Only the lithographs contain the depiction of the two dogs, the combing daughter and the mother with a pipe made from a corn cob, and in contrast to the painting, the depictions appear extraordinarily lively.

The Grozelier lithographs were distributed by Washburn himself. In his estate was an extensive list of distributors throughout the United States with the number of items taken on commission. The publication of the prints in Arkansas was not only accompanied by Washington newspaper advertisements, it was also discussed in the editorial section of the newspapers. The depiction was consistently received positively and it was emphasized again and again that Sandford Faulkner and Edward Washbourne themselves come from Arkansas and that the scene depicted is an appropriate representation of Arkansas humor. Washbourne himself protested violently in 1859 against a reproduction of the story of the Arkansas Traveler in the literary monthly The Knickerbocker , in which Arkansas was presented in a strongly derogatory manner. Washington's extensive reply was printed in full.

Grozelier's lithograph has been studied in depth as the closest possible reproduction to the Washington original. The river in the background is likely the Arkansas River , and the mountains beyond are the Ouachita Mountains , which can be safely distinguished from the Ozarks . The hut is located west of Little Rock , in the area where Sandford Faulkner claims to have had his conversation with the settler, and at the same time on the route that Edward Washbourne was often on when visiting his parents in Fort Smith .

The design of the log cabin with the saddle notches as corner connectors is characteristic of the American west of the first half of the 19th century. This does not apply to the roof, which was designed as a purlin roof and indicates a Scandinavian origin. Rafter roofs without supporting purlins were common . The purlins are covered with wooden shingles , some of which are missing, apparently an allusion to the leaky roof in Faulkner's story. The door of the hut is unnaturally wide, apparently Washbourne wanted more space here to represent the large family. Windows and a fireplace cannot be seen. While windows didn't have to be present, a fireplace was essential. He must have been outside of the picture in a corner of the hut. Contrary to recent explanations, the hut is by no means an outbuilding of a larger building complex, but an independent hut, as was common during the first settlement phase and existed until the middle of the century. It included other buildings such as a toilet, a smokehouse and a grain shed, which are not shown in the picture.

Other typical objects are shown and testify to the familiarity of the painter with the living conditions of the Wild West. This includes the wooden trough for the dogs and cattle. The ashtray on which the older son is sitting held the ashes of hardwoods. Water was poured over it, which dissolved alkalis from the ashes, could be tapped from below and served as a raw material for soap production. The tree trunk to the left of the hut may have been hollowed out as a water container, as a tanning vat or as a large mortar for grinding grain. The bottle gourds in the tree are nesting aids for birds, a simple measure for pest control. Other pumpkins served as storage vessels for everyday items such as gunpowder, lead or salt. As a valuable raw material, hides were often dried on racks or on house walls. They were the material for their own clothing - the settler's hat made of raccoon skin or his moccasins made of deerskin - or they were used as objects of exchange and merchandise. The rifle by the door has a flintlock . Although the percussion lock had already been developed, weapons with flintlocks were still used in remote Arkansas until the middle of the century. They were indispensable for self-defense and for hunting. The ax next to the ash container symbolizes the second phase of settlement, the clearing of land.

The settler's family is also typical of the early southwest. Most of the families had many children and they all wore simple clothes made of Beiderwand . The household almost always included a large number of dogs. The woman's pipe, carved out of a corn cob, was an item frequently used by both sexes until the Civil War, and the fiddle was almost indispensable if one could play on it. Selling homemade whiskey was also part of everyday life. The value of the abundant grain could be increased ten to twenty times by distilling schnapps. The clothing and equipment of the traveler and the possession of a riding horse indicate that he is a member of the upper class. For someone like him to ask a poor settler for a bed for the night, a meal and food for his horse was not unusual, but an element of the reality of life in the pioneering days. The distances between the forts and the cities were great, often more than a day's ride. A traveler could assume that he would be welcome as a paying guest, and over time the usual prices for an overnight stay with or without meals and for the feed of a horse had emerged.

It was not until the early 21st century that the historian Louise Hancox of the University of Arkansas pointed out that the interpretation of the painting, which was spread by Currier and Ives in their lithographs in 1870, has since been adopted without reflection, but that a scientific analysis of the picture has not yet taken place. Hancox sees the portrayal of the Arkansas Traveler as a representation of the social hierarchy in Arkansas immediately before the American Civil War from the perspective of one of the participants. The traveler and the settler are representatives of the plantation owners and the rural settlers; they stand as actors in the center. The settler's wife is just a caricature with her pipe, the daughter combs her hair and has no relation to her surroundings and the other children are characterized by their uniform faces and the renunciation of any individuality. After all, they are still marginal figures, but the numerically and economically significant population group of slaves does not appear in the picture.

Engraving by Currier and Ives (1870)

In 1870 the Currier and Ives printer published two lithographs titled The Arkansas Traveler and The Turn of the Tune . It was The Turn of the Tune apparently stabbed after the second painting Washbournes, it seems plausible that both paintings Currier and Ives stood as a template. The prints with an accompanying score and the dialogue text of the Arkansas Traveler were sold free of charge throughout the United States at a price of 40 cents each. This made them much cheaper than Grozelier's engravings, which were still $ 2.50. They found widespread use and made a decisive contribution to the popularity of the Arkansas Traveler melody , but without mentioning Sandford Faulkner or Edward Washbourne as originators.

Broadside by Frederick W. Allsopp (around 1895)

A Broadside was published by Frederick W. Allsopp around 1895 . The melody and a full version of the dialogue are reproduced beneath a woodcut modeled after Currier and Ives' lithographs. This Broadside sold over a thousand at a low price.

criticism

The Arkansas Territory and state established in 1836 had a reputation as a wild and lawless land in the United States and abroad. A series of travelogues contributed to this around 1840. This is what British geologist George William Featherstonhaugh called Arkansas an abyss of crime and wickedness, and lamented that there were fewer than a dozen residents in Little Rock who did not walk around with two pistols and a giant hunting knife they call Bowie knives . The picture drawn by the German adventurer and writer Friedrich Gerstäcker in his novel The Regulators in Arkansas and other publications corresponded to Featherstonhaugh's portrayal and was also known in the United States. In later decades the portrayals changed, now the simple-minded hillbilly was in the foreground as a stereotype of the Arkansas resident.

The character of the Arkansas Traveler originally came from Arkansas as well as the settler, the narrator Sandford Faulkner and the painter Edward Washbourne. It was only in later publications that the character was portrayed as a civilized traveler from the east coast who had the bad luck of having to travel through backward Arkansas. This interpretation probably went back to the variant of the narrative published by Mose Case in 1863. It aroused great displeasure at the end of the century, as it spread the negative image of backward Arkansas with its stupid and backwoods hillbillys across the United States. In 1877, a commentator for the Arkansas Gazette linked the Arkansas Traveler stereotype of the Arkansas resident to listlessness, indolence, and carelessness. Former Judge William F. Pope lamented in his 1895 autobiography that many intelligent people viewed the caricature of the settler in his leaky hut and with his disgruntled fiddle as a typical representative of the Arkansas population. The widespread painting of Washington caused immeasurable damage to the good name of the state and its people. Although there are lazy and immobile characters in every community whose sole aim is to create and attract a large number of other worthless good-for-nothing, the narrator and painter have given this subject too much attention at the expense of more important things. A year later, William H. Edmonds complained in his book The Truth about Arkansas that the Arkansas Traveler had inflicted millions in economic damage on the state. In addition to these sharp critics, there were always voices that valued the Arkansas Traveler very much.

An otherwise meaningless promotional song for the state of Arkansas from around 1940 took up the motif in its first lines: The traveler no longer finds / The fiddler at a cabin door [...] And sland'rous jests are out of date / ' Bout Arkansas, Fair Arkansas. The song was part of an elaborate campaign aimed at transforming the image of Arkansas from Bear State to Wonder State . This campaign was in turn part of the Country Life Movement , which had been aiming to improve the living conditions of Americans living in the country since the early 20th century. The Country Life Movement was particularly dedicated to the remote regions of the south such as the Appalachians and the Ozarks. Despite efforts to modernize the state and cultivate its image, the Arkansas Traveler continued to exist, and comedians like Bob Burns kept it alive. Towards the end of the twentieth century, with the increasing appreciation of unspoiled nature and life in the country, the Arkansas Traveler again became a consistently positive symbol of the state of Arkansas.

The Arkansas Traveler as namesake

media

- A humorous magazine published from 1882 to 1916 first in Little Rock and from 1887 in Chicago by Opie Read was called The Arkansaw Traveler , on its cover both scenes from the prints of Currier and Ives were reproduced. The magazine saw to it that a number of stereotyped absorbing and reproducing jokes about Arkansas and its people were spread;

- In 1920, the University of Arkansas student newspaper , The University Weekly , changed its name to The Arkansas Traveler . The newspaper appears under this name several times a week to this day;

- In the mid-1920s, the Ku Klux Klan in Little Rock published a weekly called Arkansas Traveler ;

- Comedian Bob Burns has appeared as The Arkansas Traveler since the 1930s . When he received his own radio show in 1941, it was initially also called The Arkansas Traveler , but was renamed The Bob Burns Show in January 1943 ;

- A radio show on the WDET station of Wayne State University in Detroit , Michigan , which ran from 1977 to 2004 and from 2005 to 2009 and broadcast bluegrass was called Arkansas Traveler ;

- The 1992 album Arkansas Traveler by the singer-songwriter Michelle Shocked contains folk music from various countries as well as an interpretation of Arkansas Traveler

- A US western web series published in June and July 2017 is titled Arkansas Traveler .

Sports

- A well-known racehorse of the 1840s was called Arkansas Traveler ;

- The baseball team founded in 1901 Little Rock Travelers was renamed Arkansas Travelers in 1963 , the team has played in the Southern League of minor league baseball since 1964 ;

- The American professional golfer E. J. Harrison was nicknamed Arkansas Traveler ;

- In 1949, Hazel Walker and her Arkansas Travelers founded the first women's team in professional basketball. Until 1965 they played exclusively against male teams and won 80 to 85 percent of their games.

politics

- Since 1941, people in Arkansas who are not citizens of the state have been able to qualify as Arkansas Travelers . The honor is given by the governor for service to the state of Arkansas or its people. The recipient is usually honored at a public event at which the recipient is presented with an 11 ¼ × 15 ¼-inch certificate , signed by the Governor and Secretary of State of Arkansas and stamped with the Arkansas seal . President Franklin D. Roosevelt was named the first Arkansas Traveler on May 20, 1941 ;

- In the election campaign for the presidential election in the United States in 1992 and the 1996 election, a group of Arkansas-based supporters of candidate Bill Clinton , who was then governor of the state, the Arkansas Travelers , who traveled all over the United States, called themselves the Arkansas Travelers .

Others

- A Lockheed P-38 Lightning of the United States Army Air Forces was named Arkansas Traveler and was painted with the appropriate nose art ;

- A range of pleasure boats was manufactured and sold by the Southwest Manufacturing Co. of Little Rock in the mid-20th century under the brand name Arkansas Traveler ;

- A breed of chickens bred for cockfighting is called the Arkansas Traveler or Blue Montgomery Traveler ;

- One type of tomato and one type of peach are called Arkansas Traveler ;

- In 1968 The Arkansaw Traveler Folk Theater and restaurant were established in Hardy ;

- The Arkansas Traveler tartan has been the official state tartan of Arkansas since 2001. The green represents the beauty of the forests and trees of the Ozarks, where many Scottish immigrants settled, the blue symbolizes the lakes and rivers, the yellow the sunshine in spring and summer, and the red the strong blood ties with Scotland and within Arkansas.

Early Climax locomotive , designated Arkansas Traveler 65 , circa 1890

Stove tiles by Henry Chapman Mercer with the motif of the Arkansas Traveler

Lockheed P-38 Arkansas Traveler at Clastres-Saint-Simon Airfield , October 14, 1944

literature

- Benjamin A. Botkin (Ed.): A Treasury of American Folklore. Stories, Ballads, and Traditions of the People . Crown Publishers, New York 1944, pp. 321-322 and pp. 346-349.

- Sarah Brown: The Arkansas Traveler: Southwest Humor on Canvas. In: The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 1987, vol. 46, no. 4, pp. 348-375, doi: 10.2307 / 40025957

- Mose Case: Mose Case's was songster. Containing union and war songs of his own composition. Comprising a history of the rebellion, to which is added Mose's adventures in Mexico . Franklin Printing House, Buffalo, New York 1863, OCLC 58663881

- Tom Dillard: Statesmen, Scoundrels, and Eccentrics. A Gallery of Amazing Arkansans . The University of Arkansas Press, Fayetteville 2010, ISBN 978-1-55728-927-8 .

- Louise Hancox: The Redemption of the Arkansas Traveler. In: The Ozark Historical Review. Spring 2009, Vol. XXXIIX, pp. 1–30, digital version , PDF, 592 KB

- Fennimore Harrison: The Arkansas Traveler. A New Eccentric Comedy in Four Acts . New Orleans 1881, digitized

- Henry Chapman Mercer: On the Track of the Arkansas Traveler. In: The Century Magazine. March 1896, pp. 707-712, digitized

- William F. Pope: Early days in Arkansas; being for the most part of the personal recollections of an old settler . Frederick W. Allsopp, Little Rock, Arkansas 1895, digitized . As an appendix The Arkansaw Traveler as a transcript of the dialogue between the Arkansas Traveler and the settler

- The Arkansas Traveller's Songster: Containing the Celebrated Story of the Arkansas Traveler, With the Music for Violin or Piano, and also, An Extensive and Choice Collection of New and Popular Comic and Sentimental Songs . Dick & Fitzgerald, New York City 1864, Digit 1 , Digit 2

Web links

- Arkansas Traveler in The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture (English)

- Arkansas Traveler on the Arkansas Historic Museum website

Individual evidence

- ^ William F. Pope: Early days in Arkansas. Appendix on pp. 325–330-

- ^ A b William F. Pope: Early days in Arkansas. Pp. 230-233.

- ^ Margaret Smith Ross: Sandford C. Faulkner. In: The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 1955, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 301-314, JSTOR 40027531 .

- ^ A b Sarah Brown: The Arkansas Traveler. Pp. 349-350.

- ^ Henry Chapman Mercer: On the Track of the Arkansas Traveler. Pp. 711-712.

- ↑ Thomas Wilson: The Arkansas Traveler. In: Ohio Archaeological and Historical Publications. 1900, Vol. VIII, pp. 296-308, digitized ; Reprint from Fred. J. Heer, Columbus, Ohio 1900, digitized .

- ↑ a b Ophia D. Smith: Joseph Tosso, The Arkansaw Traveler. In: Ohio History Journal. 1947, Volume 56, No. 1, pp. 16-43.

- ↑ a b c d e Mary D. Hudgins: Arkansas Traveler: A Multi-Parented Wayfarer. In: The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 1971, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 145-160, doi: 10.2307 / 40038074 .

- ↑ a b c d John Minton: 78 Blues. Folksongs and Phonographs of the American South . University Press of Mississippi, Jackson 2008, ISBN 978-1-934110-19-5 , pp. 168-210.

- ^ A b Sarah Brown: The Arkansas Traveler. Pp. 352-353.

- ^ A b c Gene Bluestein: "The Arkansas Traveler" and the Strategy of American Humor. In: Western Folklore. 1962, Vol. 21, No. 3, pp. 153-160, doi: 10.2307 / 1496953 .

- ^ A b c Henry Chapman Mercer: On the Track of the Arkansas Traveler. Pp. 707-709.

- ^ Sarah Brown: The Arkansas Traveler. P. 368.

- ^ A b c William B. Worthen: Arkansas Traveler in The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture , accessed March 5, 2019.

- ^ A b c Sarah Brown: The Arkansas Traveler. Pp. 353-354.

- ^ Robert L. Morris: The Success of Kit, the Arkansas Traveler. In: The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 1963, Vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 338-350, JSTOR 40018635 .

- ↑ a b c d Background Information: The Arkansas Traveler , CyberBee website, accessed March 5, 2019.

- ^ A b Louise Hancox: The Redemption of the Arkansas Traveler. Pp. 13-14.

- ↑ The Arkansas Traveler , website of the Arkansas Secretary of State, accessed March 5, 2019.

- ^ A b Sarah Brown: The Arkansas Traveler. P. 348.

- ^ A b c Sarah Brown: The Arkansas Traveler. Pp. 356-358.

- ^ A b Tom Dillard: Statesmen, Scoundrels, and Eccentrics. A Gallery of Amazing Arkansans. Chapter Edward Payson Washbourne. Pp. 145-147.

- ↑ a b c d e f Sarah Brown: The Arkansas Traveler. Pp. 359-366.

- ^ A b c George Lankford: The Arkansas Traveler: The Making of an Icon. In: Mid-America Folklore. Spring 1982, Vol. X, No. 1, pp. 16-23, digitized .

- ↑ Frank Fellone: Things of the past , the Arkansas Democrat Gazette website, June 21, 2015. Retrieved on March 5, 2019 (with photo of the painting).

- ^ Louise Hancox: The Redemption of the Arkansas Traveler. P. 25.

- ^ George Lankford: The Arkansas Traveler: The Making of an Icon. In: Mid-America Folklore. Spring 1982, Vol. X, No. 1, pp. 16–23, to be found on p. 18 lower center, digitized .

- ^ Louise Hancox: The Redemption of the Arkansas Traveler. Pp. 15-16.

- ^ Sarah Brown: The Arkansas Traveler. P. 369.

- ^ A b Louise Hancox: The Redemption of the Arkansas Traveler. Pp. 8-11.

- ^ Louise Hancox: The Redemption of the Arkansas Traveler. Pp. 28-30.

- ^ Louise Hancox: The Redemption of the Arkansas Traveler. Pp. 26-27.

- ^ A b Sarah Brown: The Arkansas Traveler. P. 370.

- ^ Archie Green: Graphics # 67: The Visual Arkansas Traveler. In: JEMF Quarterly. Spring / Summer 1985, Vol. XXI, No. 75/76, pp. 31-46, digitized .

- ^ Robert L. Morris: Three Arkansas Travelers. In: The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 1945, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 215-230, doi: 10.2307 / 40037537 .

- ^ C. Fred Williams: The Bear State Image: Arkansas in the Nineteenth Century. In: The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 1980, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 99-111, doi: 10.2307 / 40023900 .

- ^ Henry Chapman Mercer: On the Track of the Arkansas Traveler. P. 710.

- ^ Louise Hancox: The Redemption of the Arkansas Traveler. Pp. 18-24.

- ↑ James R. Masterson: Tall Tales of Arkansaw . Chapman & Grimes, Boston 1942, p. 302.

- ^ Sarah Brown: The Arkansas Traveler. Pp. 371-372.

- ^ Robert L. Morris: Opie Read, Arkansas Journalist. In: The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 1943, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 246-254, doi: 10.2307 / 40030597 .

- ↑ A History of the Arkansas Traveler , site of the Arkansas Traveler , accessed on 5 March of 2019.

- ^ Charles C. Alexander: Defeat, Decline, Disintegration: The Ku Klux Klan in Arkansas, 1924 and After. In: The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 1963, Vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 311-331, doi: 10.2307 / 40018633 .

- ↑ Terry Turner: Arkansas Travelers (Baseball Team) in The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture , accessed March 5, 2019.

- ↑ Tom Dillard: Statesmen, Scoundrels, and Eccentrics. A Gallery of Amazing Arkansans. Chapter Hazel Walker. Pp. 216-218.

- ↑ Awards from the Secretary of State , accessed March 5, 2019.

- ↑ Sonny Rhodes: Historical Gems: History of the Arkansas Traveler , About You Online Magazine, July 1, 2016, accessed March 5, 2019.

- ^ RA Fennell: The Relation between Heredity, Sexual Activity and Training to Dominance-Subordination in Game Cocks. In: The American Naturalist. 1945, Vol. 79, No. 781, pp. 142-151, doi: 10.1086 / 281247 .

- ^ The Arkansaw Traveler Folk Theater Program , East Carolina University Digital Collections, accessed March 5, 2019.