Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway

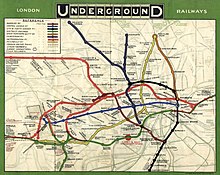

The Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway (CCE & HR, also known as the Hampstead Tube ) was a predecessor of today's London Underground , the underground railway of the British capital London . The mostly underground route now forms the Charing Cross branch of the Northern Line through the West End .

The plans to build a low-lying tube track go back to 1891. However, the promoters could not raise enough financial resources, so that the start of construction was delayed by more than ten years. In 1900, CCE & HR became a subsidiary of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) holding company controlled by the American financier Charles Tyson Yerkes . Within a short time, Yerkes and other (mostly foreign) investors were able to raise the necessary funds.

When it opened in 1907, the CCE & HR was 12.34 kilometers long and had 16 stations. The route ran from Charing Cross in the south via Euston Station to Archway and Golders Green in the north. After the opening of extensions to Edgware and Kennington , the route length grew to 22.84 km, with a total of 23 stations. In the mid-1920s, connecting lines to the City and South London Railway were opened and both lines were merged to form what would later become the Northern Line. In 1933, all private underground rail companies became public property.

founding

First plans (1891-1893)

On November 27, 1891, the London Gazette reported that a private initiative for the construction of the Hampstead, St Pancras & Charing Cross Railway (HStP & CCR) would be presented to the British Parliament (by law, Parliament had to approve all privately financed rail projects ). A completely subterranean railway was planned from Heath Street in Hampstead via Camden Town , Tottenham Court Road and Charing Cross Road to Agar Street at the western end of Strand Street in Charing Cross . A branch line should open up the Euston , St Pancras and King's Cross stations . While no decision had been made as to whether the trains should be pulled by cables or powered by electricity, a power station was planned on Chalk Farm Road, near Chalk Farm (now Primrose Hill) station on the London and North Western Railway , where the required coal could be delivered.

The promoters of HStP & CCR were inspired by the success of the City and South London Railway (C & SLR), the world's first tube-type underground railway. This was opened in November 1890 and had high passenger numbers from the start. Three similar legislative proposals for underground railways were tabled for consideration during the 1892 parliamentary session. A Joint Committee was then formed from members of the House of Commons and the House of Lords in order to be able to discuss the petitions quickly. The commission obtained information on various aspects of the construction and operation of tube railways and made recommendations on tunnel diameters, drive types and the granting of rights of way. They approved the proposed route, but prohibited the construction of the branch line beyond Euston Station. After parliamentary deliberations and the change in the company's name, the Act came into effect on August 24, 1893 as the Charing Cross, Euston, and Hampstead Railway Act, 1893 .

Search for capital (1893–1903)

Although the company now had permission to build the railway, it lacked the capital to finance the construction work. In addition to CCE & HR, four other subway companies were looking for investors - the Baker Street & Waterloo Railway (BS&WR), the Waterloo & City Railway (W&CR), the Great Northern & City Railway (GN&CR) and Central London Railway (CLR). Only the shortest line, the W&CR, easily raised the capital it needed, with the London and South Western Railway behind it with its guaranteed dividends . The other companies, on the other hand, could not find any investors during the entire 1890s, as the financial market showed no interest.

Like most laws of this type, the 1893 Act included time limits for expropriating land and raising capital (the time limits ensured that unused permits expired quickly and thus did not block future projects unnecessarily). For this reason, the CCE & HR submitted several renewal requests. Parliament granted extensions of deadlines with the Charing Cross Euston and Hampstead Railway Acts of 1897, 1898, 1900 and 1902.

In 1897 a construction company was named, but due to the lack of finances it could not carry out any work. Finally, foreign investors came to the aid of CCE & HR. The American financier Charles Tyson Yerkes , who had built a lucrative tram network in Chicago in the 1880s and 1890s , saw the opportunity to make similarly profitable investments in London. In September 1900 he took over the CCE & HR for 100,000 pounds and acquired with the support of other donors more underground societies.

With CCE & HR and the other companies under his control, Yerkes set up the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL, also known as the Underground Group ) holding company to raise funds and electrify the existing steam-powered Metropolitan District Railway . The share capital of UERL was 5 million pounds, with the majority of the shares was owned by foreign investors. More share subscriptions followed, raising a total of £ 18 million. As with many of Yerkes' ventures in the United States , the UERL's financial structure was extremely complex and relied on novel funding models that relied on future revenues (over-inflated passenger estimates meant that many investors did not get the expected profits).

Route selection (1893–1903)

When CCE & HR was still looking for capital, it developed its route planning further. On November 24, 1894, they announced a legislative initiative that would allow the purchase of additional land for stations at Charing Cross, Oxford Street, and Euston and Camden Town. Parliament approved the initiative on July 20, 1894 as the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway Act, 1894 . As part of the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway Act, 1898 , Parliament approved the relocation of the southern terminus from Agar Street to Craven Street on the south side of Charing Cross station on July 25, 1898 .

Another legislative initiative of the CCE & HR followed on November 22nd, 1998, it provided for an extension and a change to the already approved route. The extension was a branch line from Camden Town to Kentish Town station of the Midland Railway . Behind this new terminus, an above-ground depot was planned on a vacant lot . The change affected the route between Mornington Crescent and Warren Street . In this section, the route should not take the most direct route, but rather, swiveling a little to the east, it should also open up Euston station . It was also planned to purchase land on Cranbourn Street for a new station building ( Leicester Square ). Parliament approved the changes and the corresponding Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway Act, 1899 , came into effect on August 9, 1899.

On November 23, 1900, the CCE & HR announced the most far-reaching change to the route and submitted two bills to parliament. The first proposal provided for the extension of the railway from Hampstead north to Golders Green , the purchase of land for the station construction and the construction of a depot at Golders Green. Small adjustments to the already approved route were also proposed. The second template involved two extensions, north from Kentish Town to Highgate, south from Charing Cross via Parliament Square to Victoria Station . With the construction of the extension to Golders Green, the underground would leave the built-up area and advance into sparsely populated, agricultural areas. The reason for the project change was Yerkes' intention to sell the land he had recently acquired and parceled out around the planned terminus as soon as the subway was in operation and prices rose sharply.

As in 1892, both chambers of parliament formed a joint commission chaired by Lord Windsor , since in addition to the initiatives of the CCE & HR there were seven other projects for parliamentary deliberation (none of which was ultimately implemented). When the commission submitted its report, the parliamentary session was almost over and the promoters were asked to resubmit their initiatives with a view to the next parliamentary session in 1902. The CCE & HR did so in November 1901 and presented an additional initiative. This suggested a changed route to Golders Green, and a short extension was planned under Charing Cross station to Victoria Embankment , where a transfer to the existing station of the Metropolitan District Railway was to be created.

A newly formed joint commission, this time chaired by Lord Ribblesdale , re-examined the initiatives submitted. She described the sections that dealt with the proposed extensions to Highgate and Victoria Station as not compliant with the requirements of the parliamentary rules of procedure and deleted them without replacement.

Hampstead Heath controversy

A controversial part of the CCE & HR's plans was the extension of the route to Golders Green. The route of the planned subway ran under Hampstead Heath ; the fear of possible negative effects on the environment in this heathland led to the formation of a protest movement. The Hampstead Heath Protection Society believed that the tunnels would draw water out of the ground and that the vibrations from the passing trains would damage the trees. Based on the concerns of the Society, the Times published an alarming article on December 25, 1900:

“A great tube laid under the heath will, of course, act as a drain; and it is quite likely that the grass and gorse and trees on the Heath will suffer from the loss of moisture ... Moreover, it seems to be established beyond question that the trains passing along these deep-laid tubes shake the earth to its surface, and the constant jar and quiver will probably have a serious effect upon the trees by loosening their roots. "

"A large pipe laid under the heather will of course act like a drain, and it is quite likely that the grass and gorse and trees in the heather will suffer from moisture loss ... Besides, it seems beyond a doubt that that the trains running in these deep tubes will shake the earth to the surface, and the constant tremors and tremors are likely to have serious effects on the trees as their roots will loosen. "

In fact, the tunnels were supposed to run more than 60 meters below the surface, deeper than any other on the London Underground network. During the presentation to the parliamentary commission, the consultant of CCE & HR firmly rejected the objections and stated that the layer of clay to be pierced was almost less sensitive than granite. He found the fear that the trains would make the trees tremble so ridiculous that he advised the Commission not to waste their time on such questions.

A second railway company, the Edgware and Hampstead Railway (E&HR), was also planning a tunnel under Hampstead Heath. E&HR wanted to establish a connection to CCE & HR in Hampstead. In order not to have to build too many tunnels underneath the heath, both companies agreed that E&HR should link up with CCE & HR in Golders Green.

The affected borough council, the Metropolitan Borough of Hampstead , had originally spoken out against the subway line, but agreed on the condition that an additional station be built between Hampstead and Golders Green to allow visitors to Hampstead Heath access. This station should be built on the northern edge of the heather at North End and also develop a planned housing estate. When Parliament was convinced that the underground would not damage the heather, the various legislative initiatives of the CCE & HR came into effect jointly on November 18, 1902 as the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway Act, 1902 , those of the E&HR on the same day as Edgware and Hampstead Railway Act, 1902 .

Construction work and opening (1902–1907)

In July 1902, when the financing was secured and the definitive route was determined, CCE & HR began demolition and preparation work. The company released another legislative initiative to expropriate additional homes for the establishment of stations and to take over the E&HR. They also renounced the no longer necessary section from Kentish Town to the planned depot near Highgate Road. This bill was approved as the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway Act, 1903 on July 21, 1903 .

The shield driving of the tunnel tubes began in September 1903. The station buildings were designed by the architect Leslie Green in a uniform style. The two-story steel frame constructions were clad with red, glazed terracotta bricks and had semicircular windows on the upper floor. Three stations deviated from this uniform design: Golders Green station was made of bricks, Tottenham Court Road was underground and only accessible via a pedestrian underpass, and the entrance to Charing Cross station was an annex to the station concourse. Each station was equipped with two or four elevators of Otis Elevator Company appointed and an emergency staircase.

As construction progressed, the CCE & HR presented further initiatives to Parliament. The Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway Act, 1904 , approved July 22, 1904, allowed the Company to purchase additional land for the station on Tottenham Court Road, build Mornington Crescent station, and make minimal changes at Charing Cross to undertake. The Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway Act, 1905 came into force on August 4, 1905. This gave CCE & HR permission to use the entire forecourt of Charing Cross station for excavation work instead of just part of it as before.

In 1904, conservationists bought building land near the North End to add to the parkland of Hampstead Heath. As a result of this measure, the forecasts for the number of passengers who would use this station in the future had to be adjusted downwards. The CCE & HR had the platforms and part of the access tunnels completed by the end of 1906, but before the elevator shaft and the station building were built, the builders finally decided not to open this station.

The tunnel bores were completed in December 1905, after which work concentrated on completing the station building, laying the rails and setting up the signaling system. As a subsidiary of the UERL Holding, CCE & HR obtained electrical energy from the Group's own coal-fired power station, the Lots Road Power Station in Chelsea , which was originally built to electrify the steam-powered Metropolitan District Railway. The UERL therefore decided not to build the planned Chalk Farm power station. The southernmost section of the approved route between Charing Cross and Embankment was also not built for the time being.

The official opening of the CCE & HR took place on June 22, 1907 by David Lloyd George , the then President of the Board of Trade and later Prime Minister. It was free to use for the rest of the day. From the beginning, the new line was generally known under the short name Hampstead Tube or Hampstead Railway and appeared on route network maps.

The stations Charing Cross , Leicester Square , Oxford Street (now Tottenham Court Road ), Tottenham Court Road (now Goodge Street ), Euston Street (now Warren Street ), Euston , Mornington Crescent and Camden Town were put into operation on the main branch . The Chalk Farm , Belsize Park , Hampstead and Golders Green stations were added on the western branch, and South Kentish Town (closed in 1924), Kentish Town , Tufnell Park and Highgate (now Archway ) on the eastern branch .

Cooperation and Consolidation (1907-1910)

Between 1890 and 1907 no fewer than seven new underground lines with more than 70 stations were built in the London area. There were also the Metropolitan Railway and the Metropolitan District Railway , which had been founded decades earlier. The individual companies competed with each other and were also in competition with electric trams and buses. In several cases, passenger estimates before the opening had proven too optimistic. The resulting lower income made it difficult for companies to repay the borrowed capital and distribute dividends to shareholders. The UERL had also massively overestimated the passenger forecasts. In the first twelve months of operation, only 25 million passengers were carried on the Hampstead Railway, instead of the 50 million calculated during the planning phase.

In an effort to work together to improve their tense situation, most of London's underground rail companies began to coordinate fares. In addition to the UERL companies, these were the Central London Railway , the City and South London Railway and the Great Northern & City Railway . From 1908 they began to market themselves together as "underground". The Metropolitan Railway and the Waterloo & City Railway (owned by the London and South Western Railway ) were not involved in this cooperation .

The UERL companies continued to be separate legal entities with their own management and a separate shareholder and dividend structure. This resulted in an unnecessarily high administrative burden. To streamline administration and save costs, the UERL introduced a bill in November 1909 to merge the Hampstead Railway, Piccadilly Railway and Bakerloo Railway into a single company called the London Electric Railway (LER); however, the lines retained their names. The law came into force on July 26, 1910 as the London Electric Railway Amalgamation Act, 1910 . The merger came about through the transfer of assets from CCE & HR and BS&WR to GNP & BR and renaming of GNP & BR to London Electric Railway.

Extensions

| Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extension of the route in 1926 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Embankment (1910-1914)

In November 1910, the LER published a legislative initiative to reactivate the permit, unused since 1902, to build the extension from Charing Cross to Embankment. This extension was to run on a single track in a loop under the Thames and connect the ends of the two existing tunnels. A single-track station with a side platform was also planned, which would create a transfer option to the BS&WR and MDR stations. Parliament approved the project and the London Electric Railway Act, 1911 , went into effect on June 2, 1911. The new Charing Cross (Embankment) station opened on April 6, 1914.

Hendon and Edgware (1902-1924)

In the decade after the Edgware and Hampstead Railway (E&HR) was approved to operate the Edgware-Hampstead line, the company sought funding and revised its plans in coordination with the plans of CCE & HR and a third rail company, the Watford and Edgware Railway (W&ER), who planned a connection to Watford .

After the Watford and Edgware Railway Act was passed in 1906 , W&ER briefly took over the authority to build the line from Golders Green to Edgware. Since they could still not raise enough funds, the W&ER sought a formal merger with E&HR in 1906, with the intention of building the entire line between Golders Green and Watford as a branch line. But the parliament rejected the corresponding legislative initiative and the E&HR continued to exist for the time being.

In 1905, 1909, and 1912, Parliament passed laws that allowed the society to extend deadlines, changed the route, granted building permits for viaducts and a tunnel, and allowed the relocation and closure of intersecting roads. The intention was that CCE & HR should provide and operate the trains. With the entry into force of the London Electric Railway Act in 1912 , E&HR finally became part of LER in the UELR Holding.

No immediate effort has been made to begin construction. After the outbreak of World War I, they had to be postponed indefinitely, as wartime economic measures made the construction of the railway line impossible. Parliament granted the LER a one-year delay from 1916 to 1922 and finally set August 7, 1924 as the latest date for the execution of expropriations. Although the permits were still valid, the UERL was unable to raise the funds. The construction costs had increased significantly in the war years and the income did not cover the costs for the capital repayment. The project finally came to fruition when the Trade Facilities Act of 1921 came into force, which allowed the UK Treasury to provide loans for public works construction projects as a measure to reduce unemployment. With this support, the UERL now had enough capital and began construction work on the extension to Edgware.

The ground-breaking ceremony took place on June 12, 1922. The extension led through an agricultural area, so it was possible to achieve most of it above ground and at significantly lower costs. A viaduct spanned the valley of the River Brent and a short tunnel crossed Hyde Hill in Hendon . The station buildings designed by Stanley Heaps were created in a suburban pavilion style. The first section with the stations Brent (now Brent Cross) and Hendon Central was opened on November 19, 1923. The second section with the stations Colindale , Burnt Oak and Edgware followed on October 27, 1924.

The new route had a strong influence on the neighboring towns. For example, the original center of Hendon was moved more than a kilometer towards the route, so that numerous commercial buildings and even a passage were built on the previously unused ground. The significance of this new settlement focus was underpinned once again by the name of the station as Hendon Central. The better connection to London resulted in a greatly accelerated settlement development. Two years after opening, the population at the endpoint Edgware had already doubled, which was a great success for the line, as the majority of the people who moved in were potential passengers due to the low level of motorization of the population. Another success was the development of residential areas far away from the route by connecting lines, of which in Edgware alone thousands of people were transported to the trains shortly after the opening. Due to the success in terms of traffic, settlement and urban planning, the extension to Edgware is regarded as a model project for similar route extensions and as a showpiece of the Underground.

From Waterloo to Kennington (1922-1926)

On November 21, 1922, the LER published a legislative initiative for the parliamentary session of 1923. It included the proposal to extend the route of the CCE & HR from its southern terminus via Waterloo station to Kennington station, where a link with the route of the C & SLR should be created . The law went into effect as the London Electric Railway Act, 1923 on August 2, 1923. The underground part of the former CCE & HR terminus has been rebuilt and the single-track loop closed. In Kennington, two additional platforms were built, immediately south of them the link with the C & SLR line, which has existed since 1890. The extension opened on September 13, 1926.

Transfer to public ownership (1924–1933)

Despite improvements in other parts of the subway network, the individual companies continued to struggle to make a profit. Since the UERL had been owned by the highly profitable London General Omnibus Company (LGCO) since 1912 , it was able to use the profits of the bus company, which had almost a monopoly, to cross-subsidize the operation of the deficit subways. Due to the competition from numerous small bus companies at the beginning of the 1920s, LGOC's profits fell, which had a negative effect on the profitability of the entire holding.

The chairman of the UERL, Lord Ashfield , tried to convince the government to regulate local public transport in the London area. From 1923 onwards, several corresponding bills were drawn up. The main actors in the debate about the degree of regulation were Lord Ashfield and Herbert Stanley Morrison , Labor MPs for London County Council and later Secretary of State. Ashfield sought to protect the UERL from competition and control the London County Council's tram network; Morrison, on the other hand, wanted to place the entire transport system under state control. After numerous unsuccessful attempts, at the end of 1930 a template was introduced which provided for the creation of the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB). This public company was supposed to take control of the UERL, the Metropolitan Railway and all bus and tram lines in an area known as the London Transport Passenger Area (roughly equivalent to today's Greater London with smaller adjacent areas). The LPTB was a compromise - public ownership, but not complete nationalization - and began operating on July 1, 1933. On that day, all subway companies were liquidated .

The search for a suitable name for the combined routes of the CCE & HR and the C & SLR proved to be a challenge for the LPTB. Until 1933 the name Edgware, Morden & Highgate Line was in use, until 1936 Morden-Edgware Line . In 1937 the term Northern Line was introduced, in view of the (ultimately unfinished) Northern Heights Project .

→ For the history of the line after 1933, see Northern Line

literature

- Antony Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes . Capital Transport, London 2005, ISBN 1-85414-293-3 .

- JE Connor: London's Disused Underground Stations . Capital Transport, London 1999, ISBN 1-85414-250-X .

- Douglas Rose: The London Underground, A Diagramatic History . Capital Transport, London 1999, ISBN 1-85414-219-4 .

- John R. Day, John Reed: The Story of London's Underground . Capital Transport, London 2008, ISBN 978-1-85414-316-7 .

- Christian Wolmar : The Subterranean Railway: How the London Underground Was Built and How It Changed the City Forever . Atlantic Books, London 2005, ISBN 1-84354-023-1 .

- Tony Beard: By Tube Beyond Edgware . Capital Transport, London 2002, ISBN 1-85414-246-1 .

- Davis Bownes: Underground-How the tube shaped London . Penguin Books, London 2012, ISBN 978-1-84614-462-2 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Route length according to Clive's Underground Line Guides, Northern line, layout

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 26226, HMSO, London, November 24, 1891, pp. 6324–6326 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ^ Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. P. 58.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 26435, HMSO, London, August 25, 1883, p. 4825 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ^ Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. Pp. 57, 112.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 26859, HMSO, London, June 4, 1897, p. 3128 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ a b London Gazette . No. 26990, HMSO, London, July 26, 1898, p. 4506 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 27197, HMSO, London, May 29, 1900, p. 3404 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ a b London Gazette . No. 27497, HMSO, London, November 21, 1902, p. 7533 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. P. 184.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. P. 118.

- ↑ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. Pp. 170-172.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 26461, HMSO, London, November 24, 1893, pp. 6859-6860 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 26535, HMSO, London, November 24, 1894, p. 4214 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 27025, HMSO, London, November 22, 1898, pp. 7134–7136 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 27107, HMSO, London, August 11, 1899, pp. 5011-5012 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 27249, HMSO, London, November 23, 1900, pp. 7613-7616 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ^ London Gazette (Supplement). No. 27249, HMSO, London, November 23, 1900, pp. 7491-7493 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ^ Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. Pp. 93, 111.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 27379, HMSO, London, November 22, 1901, pp. 7732-7734 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ^ Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. P. 131.

- ^ A b Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. P. 137.

- ^ The Tunnel Under Hampstead Heath , The Times , December 25, 1900, quoted in: Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. Pp. 184-185.

- ↑ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. Pp. 184-185.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. P. 138.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 27497, HMSO, London, November 21, 1902, pp. 7642-7644 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 27580, HMSO, London, July 24, 1903, p. 4668 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ a b Wolmar, The Subterranean Railway , p. 185

- ↑ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. P. 188.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 27618, HMSO, London, November 20, 1903, pp. 7195–7196 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ^ London Gazette (Supplement). No. 27699, HMSO, London, July 24, 1903, pp. 4827-4828 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 27737, HMSO, London, November 22, 1904, pp. 7774-7776 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 27825, HMSO, London, August 8, 1905, pp. 5447–5448 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ Connor: London's Disused Underground Stations. Pp. 14-17.

- ↑ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. P. 186.

- ↑ Network plan from 1910

- ↑ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. P. 171.

- ↑ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. P. 191.

- ↑ Badsey-Ellis, London's Lost Tube Schemes , pp. 282-283

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 28402, HMSO, London, July 29, 1910, pp. 5497-5498 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 28311, HMSO, London, November 23, 1909, pp. 8816-8818 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 28439, HMSO, London, November 22, 1910, pp. 8408-8411 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 28500, HMSO, London, June 2, 1911, p. 4175 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 27938, HMSO, London, August 7, 1906, pp. 5453-5454 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ^ Beard: By Tube Beyond Edgware. Pp. 11-15.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 27825, HMSO, London, August 8, 1905, p. 5477 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 28300, HMSO, London, August 22, 1909, p. 7747 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ a b London Gazette . No. 28634, HMSO, London, August 9, 1912, pp. 5915–5916 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 32753, HMSO, London, October 6, 1922, p. 7072 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. Pp. 220-221.

- ↑ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. P. 222.

- ↑ Bowness: How the tube shaped London. Pp. 110-114.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 32769, HMSO, London, November 21, 1912, pp. 8230-8233 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 32850, HMSO, London, November 21, 1912, p. 5322 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. P. 204.

- ↑ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. Pp. 259-262.

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 33668, HMSO, London, November 9, 1930, pp. 7905-7907 ( PDF , accessed October 2, 2013, English).

- ↑ Wolmar: The Subterranean Railway. P. 266.

- ↑ Network plans from 1933 ( Memento from August 19, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), 1936 ( Memento from June 22, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) and 1939 ( Memento from August 19, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) with different line names

Remarks

- ^ Yerkes' consortium bought the CCE & HR (September 1900), the Metropolitan District Railway (March 1901), the Brompton and Piccadilly Circus Railway and the Great Northern and Strand Railway (both September 1901) and the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway (March 1902) . Badsey-Ellis: London's Lost Tube Schemes. P. 118.

- ↑ Before the subway was built, the land around Golders Green was worth around £ 200 to £ 300 per acre , but after construction began the price rose to £ 600 to £ 700. Wolmar, The Subterranean Railway , pp. 172-173, pp. 187

- ↑ In the order of their opening these were: City and South London Railway (1890), Waterloo & City Railway (1898), Central London Railway (1900), Great Northern & City Railway (1904), Baker Street & Waterloo Railway (1906) , Great Northern, Piccadilly & Brompton Railway (1906) and CCE & HR (1907).

- ↑ The station parts of the B & SWR, the CCE & HR and the MDR initially had different names ( Embankment , Charing Cross (Embankment) and Charing Cross ). It was not until May 9, 1915 that they were given the uniform name Embankment .