Eugène François Vidocq

Eugène François Vidocq [ øˈʒɛn fʀɑ̃ˈswa viˈdɔk ] (born July 23, 1775 in Arras , † May 11, 1857 in Paris ) was a French criminal and criminalist whose life inspired numerous writers such as Victor Hugo and Honoré de Balzac . Through his activities as the founder and first director of the Sûreté nationale, as well as the subsequent opening of a private detective agency, which was probably the first in the world, he is now considered by historians to be the "father" of modern criminology and the French police and is considered the very first detective .

Life

Eugène François Vidocq was born on the night of 23 to 24 July 1775 as the third child of the master baker Nicolas Joseph François Vidocq (1744–1799) and Henriette Françoise Vidocq (1744–1824, born Dion), who was wedded to this on September 2, 1765 ) was born in Arras on Rue du Mirroir-de-Venise (renamed Rue des Trois Visages in 1856).

Childhood and Adolescence (1775–1794)

Little is known about Vidocq's childhood. The father was educated and, since he was also a grain dealer, wealthy by the standards of the day. Vidocq had six siblings: two older brothers (one of whom had already died when Vidocq was born), two younger brothers, and two younger sisters.

Vidocq's youth were turbulent. He is described as fearless, rowdy and sly, very talented, but also very lazy. He spent a lot of time in the armory of Arras and earned the reputation of a fearsome fencer and the nickname "le Vautrin" (German wild boar ). He acquired some luxuries with petty thieves.

When he was thirteen, he stole his parents' silver dishes, but managed to get the money he received for them within a day. He was arrested three days after the theft and taken to the local Baudets Prison. It was ten days later that he found out that his own father had arranged the arrest. He was released after a total of fourteen days, but even this warning and further punishments failed to contain him.

At fourteen he stole a large amount from his family's cash box and tried to embark for America in Ostend . They cheated on him and so he ended up penniless. In order to survive, he hired himself as a juggler , working his way up from stable boy to fairground monster despite regular beatings. In this role as a Caribbean cannibal, he had to eat raw meat. He couldn't stand it for long. He switched to a group of puppeteers , but was chased out of them for bargaining with his employer's young wife. After working as a street vendor, he returned to Arras, where he begged his parents' forgiveness and was welcomed with open arms by his mother.

On March 10, 1791, he signed up to the Régiment de Bourbon and confirmed his reputation as a fearsome duelist . Within six months, he fought 15 duels, killing two men. Although he caused further trouble, he only spent a total of 14 days in prison during that time . He helped a fellow prisoner successfully escape for the first time.

After France declared war on Austria on April 20, 1792, Vidocq often had to take part in fights during the first coalition war . He took part in the Battle of Valmy in September 1792 and was promoted to Caporal der Grenadiers on November 1st . During the celebration of his promotion, he challenged a senior officer to a duel. When they wanted to put him before the court- martial, he deserted his regiment and switched to the 11 e bataillon de chasseurs ( hunters on foot ), of course without mentioning his background. On November 6, 1792 he fought under Général Dumouriez in the successful French battle at Jemappes against the Austrians. In April 1793, however, he was identified as a deserter and then followed the general when he moved to the enemy camp. After a few weeks Vidocq returned to the French camp, since he could no longer talk himself out of participating in fighting against his compatriots. A hunter friend, Capitaine, mediated for him, whereupon he was taken back to the hunters. Finally he resigned from the army after he was no longer welcomed by his comrades.

At 18 he returned to Arras and made a name for himself as a womanizer. Since his seductions often ended in duels, he found himself on January 9, 1794 in the Baudets prison, which he already knew , from which he was released on January 21.

On August 8, 1794, Vidocq, who had just turned 19, married Marie Anne Louise Chevalier, five days his senior, after pretending to be pregnant. The marriage was not happy from the start, and when Vidocq discovered that his wife was cheating on him with 14-year-old aide, Pierre Laurent Vallain, he swindled her some money and fled back to the army . They did not see each other again until 1805 because of their divorce .

Adventure Years and Prison (1795-1800)

Vidocq did not stay with the army long. In the autumn of 1794 he stayed mostly in Brussels and lived from small frauds. Then one day he came under police control, but as a deserter Vidocq had no valid papers. Posing as Mr Rousseau from Lille, he escaped while his information was being verified.

In 1795 he joined - still under the name Rousseau - the armée roulante (dt. Flying army ). This army consisted of officers who had no patent and no regiment. With the help of faked routes, ranks and uniforms, they obtained shelter and rations, but stayed far away from the battlefields. Vidocq alias Rousseau started out as a Sous-lieutenant of the hunters, but gradually promoted himself to the captain of the hussars . In this role he met a wealthy widow who took a liking to him. A superior of Vidocq made them believe that they had a young nobleman on the run in front of them. Shortly before the planned wedding, however, Vidocq got scruples and confessed. Then he left the city with a generous gift of money from her.

On March 2, 1795 he reached Paris , where he could not gain a foothold in the underworld and lost a large part of his money because of a woman. He went back north and joined a group of Bohemian gypsies , whom he in turn left for a woman - Francine Longuet - who shortly afterwards betrayed him with a soldier. He surprised and beat the two of them, whereupon the soldier sued him. Vidocq was sentenced to three months in prison in September 1795, which he was to serve at the Tour Saint-Pierre in Lille.

Vidocq was 20 and quickly adapted to prison life and customs. However, when his three months were up, he was not released. Three of his fellow prisoners had embroiled him in an escape and now he was suspected of forging documents and helping to escape. With a lot of imagination and cheek, but also thanks to the support of the now repentant Francine, he fled several times over the next few weeks, but was always quickly picked up. On one of his trips out of prison, Francine caught him with another woman, where he always hid. He went into hiding for several days and only found out later that Francine had been found injured by several knife stabs. Suddenly he was faced with an attempted murder charge, which was only dropped when Francine claimed to have inflicted the wounds on herself. His contact with Francine finally broke off when she was sentenced to half a year in prison for aiding and abetting escape. When he next met her years later, she was married.

After a long delay, the process of forging documents finally started. On December 27, 1796, Vidocq, who had always protested his innocence, and a second defendant, César Herbaux, were found guilty and each sentenced to eight years of hard labor in a bagno .

"Exhausted from all kinds of abuse, exhausted from surveillance that has doubled since my conviction, I guess I was careful not to appeal - I would have had to stay in the detention center for a few more months. What strengthened my decision was the news that the convicts were to be taken to Bicêtre immediately and from there to be attached to the main thrust for the Brest prison. I don't need to even notice that I was hoping to escape on the way. "

In Bicêtre prison , he had to wait several months for transport to the Bagno de Brest. A fellow prisoner taught him the savate fighting technique , which was often useful to him later. An attempt to escape on October 3, 1797 failed and earned him eight days in prison. The transport to Brest finally took place on November 21 . Although there was no escape on the way there, he was lucky in the Bagno itself. On February 28, 1798, he managed to escape disguised as a sailor. He was picked up again on the way because of missing papers, but while his new identity details as Auguste Duval were being checked, he stole a nun's habit in the prison hospital and escaped again with this camouflage. In Cholet he hired as drovers and found his way to Paris, Arras, Brussels, Ancer and finally Rotterdam , where he was Dutch schanghaiten . After only a brief career as a privateer , he was arrested again and taken to Douai , where he was identified as Vidocq. He was then transferred to the Bagno of Toulon , where he arrived on August 29, 1799. After a failed attempt to escape, he finally escaped again on March 6, 1800 with the help of a prostitute .

The turning point (1800-1811)

Vidocq secretly returned to Arras. His father died in 1799, so he came to live with his mother. He hid with her for almost half a year before he was recognized and fled again. Under a false identity as an Austrian, he lived for some time with a widow with whom he also moved to Rouen around 1802 . Vidocq built up a good reputation as a merchant and had his mother follow suit. Eventually his past caught up with him again, he was arrested and taken to the Louvres . There he learned that he had been sentenced to death in absentia, which he appealed on the advice of the local prosecutor. During the next five months while he waited for a result in prison, Louise Chevalier notified him of the divorce. On November 28, 1805, he finally escaped again by jumping out of a window into the passing Scarpe in an unsupervised moment . He spent the next four years on the run again.

He stayed for some time in Paris, where he witnessed the execution of César Herbaux, the man who had started his problems years earlier when he was convicted of forgery. At Vidocq, a rethinking process started for the first time. Together with his mother and a woman - he called her Annette in his memoirs - whom he still called the love of his life years later, he moved several times over the next few years. Again and again he met people from his past who blackmailed the businessman who had meanwhile gotten money.

On July 1, 1809, Vidocq was arrested again shortly before his 34th birthday. He finally decided to end his life on the fringes of society and offered his services to the police. His offer was accepted and on July 20th he was locked up in Bicêtre, where he began his work as an informant . On October 28, he continued this work in the Paris State Prison La Force . For a total of 21 months he listened to his fellow prisoners and passed on his information on falsified identities and previously unsolved crimes to the Paris police chief Jean Henry via Annette.

“I thought I could have remained a spy forever, so far from the thought of suspecting me to be a police agent. Even the door closers and guards had no idea about the mission entrusted to me. I was downright adored by the thieves, the rudest bandits respected me - these people too know a feeling that they call respect. I could count on their devotion at all times. You would have liked to walk through the fire for me. "

Eventually, Vidocq was released from prison on Henry's recommendation. In order not to cause mistrust among his fellow prisoners, an "escape" was arranged, which took place on March 25, 1811. He was not free because of that, because he was now obliged to Henry. Therefore, he continued his work for the Paris police as a secret agent . He used his contacts and the reputation of his name in the demi and underworld to gain trust, disguised himself as an escaped convict, dived into the network of helpers in the criminal scene and arrested wanted criminals, some with his own hands. His success rate was high.

The Sûreté (1811-1832)

At the end of 1811, Vidocq unofficially organized the Brigade de la Sûreté (German security brigade ). After the police ministry recognized the value of civil agents, the experiment officially became a security agency under the umbrella of the Paris police in October 1812. Vidocq was appointed their boss. On December 17, 1813, Napoleon Bonaparte finally signed a decree that turned the brigade into a state security police, which from that day called itself Sûreté nationale .

The Sûreté initially had eight, then twelve, and finally 20 employees in 1823, and in the following year was increased to 28 secret agents. In addition, there were eight people who worked in secret for the security agency, but received a license for an arcade instead of a salary . Like Vidocq himself, the majority of his subordinates came from a criminal background. Some he took out of the Bagnos for their work, such as Coco Lacour, whom he himself had brought to prison as a spy in his early days and who would later become his successor as head of the Sûreté. Vidocq described the service from that time:

“With this tiny staff, more than twelve hundred people released from penitentiaries and prisons and similar individuals had to be supervised, four to five hundred arrests carried out both in the name of the police prefect and the judicial authorities, investigations carried out, all kinds of corridors taken care of, the various night rounds so arduous in winter be made. In addition, the security brigade had to support the police commissioners with house searches and oral interrogations, visit the public meetings in and outside the city and the entrances to the theaters, the boulevards, the taverns outside the gates and all other places where bag cutters and rascals rendezvous give, monitor. "

Vidocq trained its agents personally, e.g. B. in terms of the right costumes for an order. He himself still went hunting for criminals. His memoirs contain numerous stories about how he outwitted criminals of all kinds, be it as an abandoned husband who had long since passed through his prime, or as a beggar. He didn't even shrink from simulating his own death.

But despite his position as chief of a police agency, Vidocq was still a wanted criminal. He had never fully served his conviction for forging documents and so his superiors received complaints and denunciations as well as inquiries from the Douai prison director, which were ignored. It was not until March 26, 1817, that Comte Jules Anglès , the Paris prefect of police , arranged for Vidocq's official pardon from King Louis XVIII on a petition .

In November 1820 Vidocq married again, the destitute Jeanne-Victoire Guérin, whose origin is unknown, which led to some speculation at the time. She moved to his house at 111 rue de l'Hirondelle, where Vidocq's mother and her niece, the 27-year-old Fleuride-Albertine Maniez (born March 22, 1793), also lived. In 1822 he met Honoré de Balzac , who used Vidocq as a model for several figures in his works. Vidocq's wife, who was ailing during their married life, died in a hospital less than four years after the marriage in June 1824. Six weeks later, on July 30th, his 83-year-old mother, whom he had funerally buried, also died.

Several events occurred during the 1820s that also affected the police apparatus. After the assassination of the Duc de Berry in February 1820, the previous police prefect Anglès had to resign and was replaced by the Jesuit Guy Delavau , who attached great importance to the religiosity of his subordinates. Louis XVIII died in 1824. His successor was the ultra-reactionary Karl X , who ruled repressively and for this purpose repeatedly dismissed agents from their actual activities. Finally, Police Chief Henry, who had employed Vidocq years earlier, also retired . He was followed by Parisot, who was quickly replaced by the ambitious but also very formal Marc Duplessis. The dislike between him and Vidocq was great. Duplessis repeatedly complained about the stays of Vidocq's agents in brothels and bars with a bad reputation, where they made contacts and gathered information. After Vidocq received two warnings within a very short time, he had enough. On June 20, 1827, the 52-year-old submitted his resignation:

«Depuis dix-huit ans, je sers la police avec distinction. Je n'ai jamais reçu un seul reproche de vos prédécesseurs. Je dois donc penser n'en avoir pas mérité. Depuis votre nomination à la deuxième division, voilà la deuxième fois que vous me faites l'honneur de m'en adresser en vous plaignant des agents. Suis-je le maître de les contenir hors du bureau? Non. Pour vous éviter, monsieur, la peine de m'en adresser de semblables à l'avenir, et à moi le désagrément de les recevoir, j'ai l'honneur de vous prier de vouloir bien recevoir ma démission. »

“I served the police with distinction for eighteen years. I never received a single accusation from your predecessors. So I have to believe that I never deserved one. This is the second time since you were appointed to the Second Division that you have done me the honor of reaching out and complaining about my agents. Am I their lord and master in their off-duty times? No. In order to save you, sir, the trouble of turning to me with further similar complaints in the future, and the inconvenience of maintaining them myself, I have the honor to ask you to accept my abdication. "

He then wrote his memoirs , in which he outlined the necessity and effectiveness of his security police and opposed the political police:

“Because political police means: an institution brought about by the desire to enrich itself at the expense of the state, whose unrest is constantly artificially kept in suspense. Political police is synonymous with the need to draw secret funds from the budget, with the need of certain officials to show themselves to be indispensable by showing the state in alleged danger. "

Vidocq, who was a wealthy man after retiring, became an entrepreneur. In Saint-Mande , a town north of Paris, where he married his cousin Fleuride Maniez on 28 January 1830, he founded a paper mill and turned mostly laid-off convicts - both men and women - a. This represented an outrageous scandal that led to confrontations with society. In addition, the machines cost money, the workers, who first had to be trained, needed food and clothing, and finally his customers refused to pay market prices. The company could not last long - Vidocq went bankrupt as a manufacturer in 1831 . Police Prefect Delavau and Police Chief Duplessis had to resign in his absence and abdicate Charles X during the July Revolution of 1830 . After Vidocq provided valuable tips on uncovering a break-in, the new police prefect Henri Gisquet reinstated him as head of the Sûreté.

But criticism of him and his organization grew. On June 5, 1832 his troops reportedly went before with great force against unrest that during a cholera - epidemic at the funeral of General Jean Maximilien Lamarque broke out and the throne of the "citizen king" Louis-Philippe at risk. In addition, Vidocq was suspected of having initiated the theft, the investigation of which brought him his reinstatement, to prove his indispensability. One of his agents was sentenced to two years in prison for the affair. After all, defense attorneys increasingly cited the fact that their past as criminals made him and his agents unbelievable as eyewitnesses. This finally made Vidocq's position untenable. On November 15, 1832, he resigned again on the pretext that his wife was sick.

«J'ai l'honneur de vous informer que l'état maladif de mon épouse m'oblige de rester à Saint-Mandé pour surveiller moi-même mon établissement. Cette circonstance impérieuse m'empêchera de pouvoir à l'avenir diriger les opérations de la brigade de sûreté. Je viens vous prier de vouloir bien récepter ma démission, et recevoir mes sincères remerciements pour toutes les marques de bonté dont vous avez daigné me combler. Si, dans une circonstance quelconque, j'étais assez heureux pour vous servir, vous pouvez compter sur ma fidélité et mon dévouement à toute épreuve. »

“I have the honor to inform you that my wife's sickness is forcing me to stay in Saint-Mandé to supervise my establishment myself. This urgent circumstance will prevent me from directing the operations of the security brigade in the future. I ask you to accept my abdication and to receive my sincere thanks for all the tokens of kindness with which you have been deigned to shower me. If, under any circumstance, I am happy to serve you [again], you can definitely count on my loyalty and dedication. "

On the same day, the Sûreté was dissolved and re-established. Agents with criminal records were no longer allowed. Vidocq's successor was Pierre Allard.

Le bureau des renseignements (1833–1848)

Vidocq founded Le bureau des renseignements (German news agency ) in 1833 , a company that can be classified between a detective or information bureau and a private police force and is the first company of its kind. Again he mainly hired former criminals. His troop, which initially consisted of eleven detectives, two officials and a secretary, took on the fight against faiseurs (crooks, fraudsters, bankrupts) on behalf of business and private individuals , and occasionally also used illegal means. From 1837 he was in constant disputes with the official police because of his work and vague relationships with various government agencies such as the War Ministry. On November 28, 1837, the police carried out a house search and confiscated over 3,500 files and documents. Vidocq was arrested a few days later and spent Christmas and New Years in prison. He has been charged with three crimes, namely the appropriation of money through fraudulent misrepresentation, the corruption of civil servants and the presumption of public functions. In February 1838, after hearing numerous witnesses, the responsible judge rejected all three charges and Vidocq was released again.

Vidocq's person was increasingly the subject of literature and public discussion. Balzac wrote several novels and plays in which characters based on Vidocq's model appeared.

The agency flourished, but Vidocq continued to create enemies, some of them powerful. On August 17, 1842, 75 police officers on behalf of the Paris Police Prefect Gabriel Delessert stormed his office building and arrested him and one of his agents, this time the case seemed unequivocal. He had made an unlawful arrest in an investigation into embezzlement and demanded a bill of exchange from the arrested fraudster for the money that had been fraudulent . The now 67-year-old Vidocq spent the next few months in custody in the conciergerie . The first hearings before the judge Michel Barbou, a close friend of Delessert's, did not take place until May 3, 1843. During the negotiations, Vidocq also had to account for many other cases, including the kidnapping of several women whom he allegedly brought to monasteries against their will on behalf of their families. His activity as a financier and any benefits he had derived from it were also examined. The court eventually sentenced him to five years' imprisonment and a fine of 3,000 francs . Vidocq appealed immediately and, through the intervention of political friends such as Count Gabriel de Berny and the Attorney General Franck-Carré, quickly received a new trial, this time before the presiding judge of the court royale . The trial on July 22, 1843 was a matter of minutes, and after eleven months in the conciergerie, Vidocq was a free man again.

But the damage was done. The procedure was very expensive and its reputation had been damaged, which is why business in the agency no longer ran properly. To this end, Delessert tried to have him expelled from the city as a former criminal. The attempt failed, but Vidocq considered getting rid of the agency more and more often. Only qualified and at the same time reasonably serious buyers were missing.

In the years to come, Vidocq published several small books in which he presented his life, in direct confrontation with the free descriptions that were circulating about him. He also submitted an essay in 1844 on prisons, penitentiaries and the death penalty . On the morning of September 22, 1847, his third wife, Fleuride, died after 17 years of marriage. Vidocq no longer married, but lived with partners until the end of his life.

In 1848 the February Revolution broke out in Paris , during which the “citizen king” Louis-Philippe was deposed. The Second Republic with Alphonse de Lamartine at the head of a transitional government was proclaimed. And although Vidocq had previously been proud of his receptions at court and boasted of his access to Louis-Philippe, he now offered his services directly to the new government. His task for the next few months was to monitor political opponents such as Charles-Louis-Napoléons , the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte . Meanwhile, the new government sank into chaos and violence. In the presidential election scheduled for December 10, 1848, Lamartine received fewer than 8,000 votes. Vidocq himself stood for election in the 2nd arrondissement , but received only one vote. The clear winner and thus President of the Second Republic was Charles-Louis-Napoléon, who did not respond to Vidocq's offer to work for him.

The last years (1849-1857)

Vidocq was briefly jailed one last time in 1849, but charges of fraud were dropped. He withdrew more and more into private life and mostly only took on small jobs. In the last few years of his life, he suffered massive pain from an arm that was broken in fighting and never healed properly. In addition, bad investments had cost him a large part of his wealth, which is why he had to reduce his standard of living and rent again. In August 1854 he survived the cholera despite different prognoses from his doctor . It was not until April 1857 that his condition deteriorated to such an extent that he was no longer able to get up. On May 11, 1857, Vidocq died at the age of 82 in the presence of his doctor, his lawyer and a pastor.

“Je l'aimais, je l'estimais… Je ne l'oublierai jamais, et je dirai hautement que c'était un honnête homme! »

"I liked him, I appreciated him ... I will never forget him, and I can only say he was an honest man!"

His body was taken to the Saint-Denys church , where the funeral service was held. It is not known where Vidocq is buried, so there are some rumors about it. One of them, for example, mentioned in the biography of John Philip Stead, is that his grave is in the Saint Mandé cemetery. There is a tombstone with the inscription "Vidocq 18". According to the city, however, this grave is registered on Vidocq's last wife Fleuride-Albertine Maniez.

In the end, his fortune consisted of 2907.50 francs from the sale of his goods and 867.50 francs of his pension. A total of eleven women registered as the owners of a last will that they had received for their favors instead of gifts. His remaining fortune went to Anne-Heloïse Lefèvre, with whom he had finally lived. Vidocq had no children, at least none known. Attempts at recognition by Emile-Adolphe Vidocq, the son of his first wife, who had changed his surname for this purpose, failed. Vidocq had left evidence that excluded his paternity. He was in prison at the time of conception.

Vidocq's person

Even if a large number of literary and supposedly real writings depict the life and person of Vidocq or at least lean on him, his memoirs from 1827 remain the best source for capturing his personality. His biographers agree: Vidocq was a one-dimensional person with a narrow view of life and his time.

He lived in turbulent times, the French Revolution shaped the environment of his youth, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Napoleonic wars were the reason for his entry into the army. The Restoration gave him the opportunity not only to join the Paris police, but to shape them, and the riots of 1832, and finally the February Revolution, turned society into disarray. Vidocq did not see any of this. He was only interested in his own life.

"For Vidocq, eruptions under which Europe changed national borders only exist to the extent that they help him to eat and women."

The wars were only an opportunity to go into hiding, the state existed in terms of names, passports and criminal records. Vidocq never developed any understanding of the state or society of his own. His easy way of switching sides was the logical consequence; he knew no loyalty, he felt nothing connected - not his wives, his comrades, the members of his troops or an idea.

Criminal Legacy

Vidocq is now regarded by historians as the "father" of modern criminalistics. His approach was novel and unique for the time. He is credited with introducing undercover work, ballistics tests and the file card system to the police. His work was not recognized in France for a long time due to his criminal past. In September 1905, the Sûreté Nationale exhibited a series of paintings with the former heads of the authority. The first painting in the series, however, showed Pierre Allard, whom Vidocq had proposed as his successor. The newspaper L'Exclusive reported on September 17, 1905 that when asked about the omission it had received the information that Vidocq had never been head of the Sûreté.

Redesign of the police apparatus

When Vidocq switched to the police around 1810, there were two police organizations in France: On the one hand the police politique (dt. Political police ), whose agents deal with the uncovering of conspiracies and intrigues, on the other hand the normal police, the everyday police Investigated crimes such as theft, fraud, prostitution, and murder. As early as the Middle Ages, their gendarmes wore identification insignia , from which complete uniforms had developed over time. In contrast to the covert political police, they were easy to recognize. The uniformed gendarmes could not venture into some Parisian districts for fear of assault, their possibilities in crime prevention were accordingly limited.

Vidocq persuaded his superiors to use the agents of his security brigade, which included women, in civilian clothes or disguised according to the situation. They did not attract attention and, as former criminals, knew the hiding places and methods of the criminals. Through their contacts, they sometimes learned of planned crimes and often caught the criminals in the act. Vidocq's interrogations also went differently than usual: In his memoirs, he recounts several times how he did not drive directly to prison with those who had just been arrested, but instead invited them to dinner, where he talked to them. In addition to information about other crimes, which he often received casually, this nonviolent method often resulted in confessions and the recruitment of future informants and even agents.

August Vollmer , Berkeley's first police chief and one of the leading figures in the development of the criminal investigation system in the United States , dealt primarily with the works of Vidocq and the Austrian criminologist Hans Gross as part of the police reform . His reforms were adopted by the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), of which he was president, and consequently affected J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI he headed , founded in 1908 by Bonaparte's great-nephew Charles Joseph Bonaparte . Robert Peel , who founded Scotland Yard in his capacity as British Home Secretary in 1829 , sent a commission to Paris in 1832, which discussed with Vidocq for several days. In 1843 two commissioners from Scotland Yard again traveled to Paris for further training. However, they only spent two days with Sûreté boss Allard and then went to Vidocq. For a week they accompanied him and his agents on their work.

Identification of criminals

Jürgen Thorwald certifies that Vidocq has a photographic memory in his work The Century of Detectives , which enabled him to recognize criminals who had already become conspicuous at any time, even in disguise. The biographer Samuel Edwards reports in The Vidocq Dossier of a trial against the fraudster and forger Lambert, in which he referred himself to his memory. Vidocq visited prisons regularly to memorize the detainees. His agents were also obliged to make these visits. The English police adopted this method. Up until the late 1980s, English detectives attended court hearings in order to observe spectators in the public galleries and to become aware of possible accomplices.

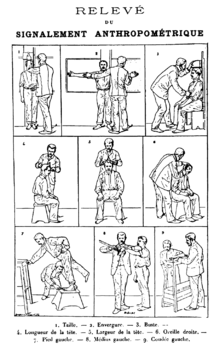

As Vidocq said at Lambert's trial, while his memory was phenomenal, he could not assume that his agents were. He therefore carefully created an index card for each person arrested, containing a description of the personnel, pseudonyms, previous convictions, the typical procedure and other information. The forger Lambert's index card contained, among other things, a handwriting sample. The index card system was not only retained by the French police, but also adopted by police units in other countries. However, it also revealed its weaknesses over the next few years. When Alphonse Bertillon came to the Sûreté as an assistant clerk in 1879, the descriptions of the criminals on the cards were no longer detailed enough to actually identify suspects with their help. This prompted Bertillon to develop an anthropometric system of personal identification, the Bertillonage . The sorting of the filing boxes, which at that time already filled several rooms, was changed to body measurements, the first of many attempts to improve the structure and structure of the sorting. With the beginning of the information age , the index cards were digitized and the index card systems were replaced by database systems. These include databases managed by the FBI such as the biometric IAFIS, an AFIS that contains all fingerprints collected in the United States, the MUPS (Missing / Unidentified Persons System) , which contains data on missing people and unidentified bodies, and the NIBRS ( National Incident Based Reporting System) , which documents criminal incidents.

Experiments - Belief in Science

A forensic science did not yet exist to Vidocq times. Despite numerous scientific treatises, the practical benefit had not yet been recognized by the police, which was not to change Vidocq either. Nevertheless, he was not as averse to experiments as his superiors and had usually set up a small laboratory in the respective office building. The Paris police archives contain a number of reports of cases which he used forensic methods decades before they were actually recognized.

- Chemical compounds

- In France in Vidocq's time there were already checks and bills of exchange . Counterfeiters bought up checks and changed them in their favor. To address the problem, Vidocq commissioned two chemists in 1817 to develop a forgery-proof paper. This paper, for which Vidocq has applied for a patent, was treated with chemicals that, if changed, would smear the ink, which could reveal counterfeit checks. According to the biographer Edwards, Vidocq made extensive use of his contacts and promoted the paper to the cheated, mostly bankers, who hired him to research the scammers. As a result, the paper was widely used. Vidocq also used it for its index cards in order to emphasize their reliability in court. He also had an ink made that could no longer be made invisible. This was used by the French government for printing banknotes from the mid-1860s.

- Crime Scene Investigations

- Louis Mathurin Moreau-Christophe , contemporary inspector general of the French prisons, describes in his book Le monde des coquins how Vidocq used traces at the crime scene to identify the perpetrator based on his knowledge of the criminals and their approach. As a specific example, Moreau-Christophe cites a burglary in the Bibliothèque Royale in 1831, during the investigation of which he was also present. Vidocq inspected a panel of the door that the perpetrator had broken open and explained that due to the method used and the perfection with which this would have been carried out, only one perpetrator could actually be considered, the thief Fossard, who is currently in the Jail. He then received from the police chief Lecrosnier, who was also present, that Fossard had broken out eight days ago. Two days later, Vidocq was able to arrest the thief who had actually committed the break-in.

- Forensics

- The index card for the thief Hotot documents one of the first cases of the conviction of a criminal through the shoe prints left on the scene. The thief he knew had caught Vidocq's attention because of his wet and mud-stained clothing. When he was called to the scene of a theft, he saw shoe prints in the garden of the house. He fetched the thief's shoes and had them compared with the tracks. Faced with the match of the prints, the thief confessed. Around 1910, the forensic pioneer Edmond Locard , director of the French police laboratory in Lyon, formulated the principle already used by Vidocq as Locard's rule : no contact without material transfer . Its use, which includes finger and shoe prints as well as tire and smoke marks, fibers, DNA residues and much more, is now a common means of convicting offenders and is carried out by experts.

- Dactyloscopy

- Fingerprints were already used as signatures by the ancient Babylonians and Native Americans of Nova Scotia . In 1684, the British botanist Nehemiah Grew first wrote a work on the patterns on the fingertips, which he presented to the Royal College of Physicians of London . In 1823 Jan Evangelista Purkyně published a work in which he wrote about the individuality of fingerprints and made a first classification. It is not known whether Vidocq read this work, but both Balzac and Hugo both left notes, according to the biographer Edwards, which indicate that he was into fingerprinting from around this time and, for that purpose, also became a Huygens - Microscope increased. Apparently he was discussing his experiments with his friends and was firmly convinced that he could use them to identify criminals. Dumas wrote that Vidocq had been looking for a physicist whom he could convince of his ideas. Meanwhile, he 'persuaded' prisoners from Bicêtre to take their fingerprints. He found that normal ink smeared during this process. His own ink was also unsuccessful, as it dried too quickly, leaving only weak marks and also stuck to the fingers of his guinea pigs for weeks. Moist clay panels produced significantly better prints, but they took up too much space in the archive rooms. By the time he left the Sûreté for the first time, Vidocq had not found a satisfactory solution for securing fingerprints and later did not pursue this project any further, as he could not convince a physicist to support him. He did not find out that Ivan Vučetić had found a suitable means with simple ink . However, he believed in the usability of fingerprints until the end of his life and discussed the subject often, including in an interview with two reporters for the London Times and the New York Post in 1845 . A year after his death, William Herschel introduced the use of fingerprints to prevent pension fraud in India. In 1888 Francis Galton published his first work on the uniqueness of fingerprints, paving the way for dactyloscopy in Europe. In 1892, a murder was first solved in Argentina with the help of this science, which is now a standard procedure.

- ballistics

- Alexandre Dumas left records describing an 1822 murder case. The Comtesse Isabelle d'Arcy, who was much younger than her husband and had cheated on him, was found shot, whereupon the police arrested the Comte d'Arcy. Vidocq had spoken to the man and was of the opinion that the 'old gentleman' did not have the personality of a murderer. He examined his dueling pistols and found that they had either not been fired or had been cleaned since then. He then persuaded a doctor to secretly remove the bullet from the nobles' heads. A simple comparison showed that the bullet was far too big to come from the Comte's pistols. Thereupon Vidocq searched the apartment of the lover of the murdered and found in it, in addition to numerous pieces of jewelry, a large pistol, which the bullets matched the size. The Comte identified the jewelry as his wife's. Vidocq also found a fence on whom the suspect had already put a ring. Faced with the evidence, the lover confessed to the murder. The first correct comparison between a weapon and a bullet was made in 1835 by Henry Goddard, a " Bow Street Runner ". On December 21, 1860, the London Times reported on a court ruling in which the murderer Thomas Richardson was sentenced to death in Lincoln for the first time using only ballistics.

In 1990 the Vidocq Society was founded in Philadelphia . Its members are forensic experts, FBI profilers , investigators from the homicide squad, scientists, psychologists and coroners who, at their monthly meetings, examine unexplained old cases from all over the world free of charge and, according to their motto, Veritas veritatum (German: truth creates truth ), try to find the respective To provide investigators with new leads.

Cultural reception

Literary

Around 1827 Vidocq wrote an autobiography about his previous life, which he wanted to publish in the summer of 1828 at the bookseller Emile Morice. The authors' friends Honoré de Balzac , Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas found the thin book too short, so Vidocq looked for a new publisher. This, Louis François L'Héritier , published the memoir in December of the same year, which with the help of some ghostwriters had grown to four volumes. The work became a bestseller and, according to biographer Samuel Edwards, sold over 50,000 times in the first year. The success stimulated imitators. In 1829 two journalists published the book Mémoires d'un forçat ou Vidocq dévoilé under the pseudonym of the criminal Malgaret , which was supposed to uncover Vidocq's alleged criminal activities. Other police officers followed Vidocq's example and wrote their own biographies over the next few years, including Police Prefect Henri Gisquet.

With his life story, Vidocq also inspired many contemporary writers, many of whom he counted among his close circle of friends. In Balzac's writings he regularly forms the model for literary figures. In the third part of Illusions perdues (1837–1843, German lost illusions ) - Souffrance de L'Inventeur (German the sufferings of the inventor ) - his experiences as a failed entrepreneur are taken up, in Gobseck (1829) Balzac first presents the policeman Corentin but the connection between Vidocq and the figure of Vautrin is most evident. This first appears in Balzac's novel Father Goriot (1834, French Le Père Goriot ), then in Illusions perdues, Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes (as the main character), La Cousine Bette, Le Contrat de mariage and is ultimately the main character in the play Vautrin from 1840. Vidocq's methods and disguises also inspire Balzac to have many other references in his work.

In Victor Hugo's Les Misérables (1862, dt. When the poor ) are modeled on the characters both Jean Valjean and Inspector Javert Vidocq; likewise the policeman Jackal from Les Mohicans de Paris (1854–1855, Ger. The Mohicans of Paris ) by Alexandre Dumas. He was the basis for Monsieur Lecoq , an inspector who starred in many of Émile Gaboriau's adventures , and for Rodolphe de Gerolstein , who did weekly justice in Eugène Sue's newspaper novels . And it can also be found in the work The Double Murder on Rue Morgue by Edgar Allan Poe and the stories Moby Dick by Herman Melville and Great Expectations by Charles Dickens , which founded the crime fiction genre .

theatre

Vidocq was - given his preference for disguises - a great friend of the theater . In the Parisians his lifetime the so-called was Boulevard du Crime (dt. Boulevard of Crime ) quite popular. There were several theaters on this street, in which crime stories were presented every evening in the form of melodramas . One of these theaters was the Théâtre de l'Ambigu-Comique , which Vidocq sponsored and supported on a large scale. According to biographer James Morton, he also submitted a piece himself, but it was never produced. He also had plans to try himself as an actor, which he never realized.

Many of his lovers were actresses, but many of his friends and acquaintances also came from the theater scene. Among them was the well-known actor Frédérick Lemaître , who, among other things, took on the leading role in the production of Balzacs Vautrin when the play was premiered on March 14, 1840 after numerous problems with censorship in the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin . He tried to match his appearance as much as possible to that of Vidocq, on whom the figure was based. Even at the premiere, there were tumults, because the chosen wig was too similar to that of King Louis-Philippe, which is why the piece was not performed a second time after a corresponding ban by the French interior minister.

But not only the works inspired by Vidocq made it onto the stage, his own life story with the memoirs as a literary model was also performed several times. Enthusiasm for Vidocq was particularly great in England. His memoirs were quickly translated into English, and just a few months later, on July 6, 1829, Vidocq! Was premiered in the Surrey Theater in London's Lambeth district . The French Police Spy took place. The 2-act melodrama, produced by Robert William Elliston , was penned by Douglas William Jerrold . Vidocq's role was taken over by TP Cooke, who also starred in Jerrold's hit Black-eyed Susan from the same year. Although the reviews u. a. were thoroughly positive in The Times , the play was performed only nine times in the first month and then canceled.

A few years after Vidocq's death, another play based on Vidocq's memoir, written by F. Marchant, was performed at the Britannia Theater in Hoxton in December 1860 under the title Vidocq or The French Jonathan Wild , which was only scheduled for a week.

In 1909 Émile Bergerat wrote the melodrama Vidocq, empereur des policiers in 5 acts and 7 scenes. The producers Hertz and Coquelin refused, whereupon Bergerat successfully sued them for 8,000 francs in damages. The play was then premiered in 1910 at the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt . Jean Kemm , who years later would also be involved in a film about Vidocq, took on the leading role.

Film adaptations

- The first film about Vidocq was made as early as 1909. On August 13, 1909, the short- silent film La Jeunesse de Vidocq ou Comment on devient policier based on Vidocq's memoirs appeared in France. Vidocq was played by Harry Baur , who also played the role in the two sequels L'Évasion de Vidocq (1910) and Vidocq (1911).

- The next silent film, Vidocq , was made under the direction of Jean Kemm in 1922 , the screenplay of which was designed by Arthur Bernède based on the memoirs. René Navarre played the main role .

- The first sound film was released in 1938. Jacques Daroy directed the film, again named after the main character, with André Brulé as Vidocq. The film , which largely deals with Vidocq's criminal career, was rather lackluster compared to contemporary crime films, but was still played outside of France.

- On 19 July 1946, the first published by Americans turned film about Vidocq - An elegant crook . George Sanders portrayed Vidocq in Douglas Sirk's film adaptation, which shows the rise of a crook in society combined with a love story. A French version of Vidocq's life story followed again in April 1948. Le Cavalier de Croix-Mort was filmed in 1947 by Lucien Ganier-Raymond with Henri Nassiet in the lead role.

- From January 7, 1967, the French TV station ORTF broadcast the first of two television series. Vidocq with Bernard Noël in the title role, 13 episodes of 26 minutes each, like all previous films in black and white. The second series Les Nouvelles Aventures de Vidocq premiered on January 5, 1971. Claude Brasseur embodies Vidocq in 13 color episodes of 55 minutes each .

- In 2001, Vidocq finally appeared as a mixture of fantasy and horror, directed by Pitof . The figure Vidocq is represented in it by Gérard Depardieu with all his peculiarities and talents relatively authentically, but the depicted events around the "alchemist" never really happened.

- In 2018 another film adaptation by Jean-François Richet with Vincent Cassel in the title role was released with Vidocq - Ruler of the Underworld .

Remarks

- ↑ The current French name is sanglier . Vautrin is a dialect term for wild boar in northern France ( Artois and Picardy ), presumably from the reflexive verb se vautrer (dt. To wallow ) derives.

Additional information

Works by Vidocq

- Mémoires de Vidocq, chef de la police de Sûreté, jusqu'en 1827. 1828 ( digitized ). German translation by Ludwig Rubiner from 1920: Landstreicherleben as full text on Wikisource (biography).

- Les voleurs. Paris 1836, Roy-Terry ( digitized , a study of thieves and swindlers).

- Dictionnaire d'Argot. 1836 ( PDF; 982 kB ; an Argot dictionary).

- Considérations sommaires sur les prisons, les bagnes et la peine de mort. 1844 ( PDF ; 208 kB; considerations on ways to reduce crime).

- Les chauffeurs du nord. 1845 (memories of his time as a gang member).

- Les vrais mystères de Paris. 1844 (novel written by Horace Raisson and Maurice Alhoy, but published under Vidocq's name for promotional reasons).

Biographies (selection)

- Samuel Edwards: The Vidocq Dossier. The story of the world's first detective . Houghton Mifflin, Boston, Mass. 1977, ISBN 0-395-25176-1 (However, this work contains many errors, some of which are very obvious).

- Louis Guyon: Biography of the Commissaires et des Officiers de Paix de la ville de Paris . Édition Goullet, Paris 1826.

- Edward A. Hodgetts: Vidocq. A Master of Crime . Selwyn & Blount, London 1928.

- Barthélemy Maurice: Vidocq. Vie et aventures . Laisné, Paris 1861.

- John Philip Stead: Vidocq. The King of Detectives ( Vidocq. Picaroon of Crime ). Union Deutsche Verlags-Gesellschaft, Stuttgart 1954.

- James Morton: The first detective. The life and revolutionary times of Vidocq; criminal, spy and private eye . Ebury Press, London 2005, ISBN 0-09-190337-8 .

- Jean Savant: La vie aventureuse de Vidocq . Librairie Hachette, Paris 1973.

About Vidocq's Impact on Criminology

- Clive Emsley, Haia Shpayer-Makov: Police Detectives in History, 1750–1950 . Ashgate Publishing, Aldershot 2006, ISBN 0-7546-3948-7 .

- Gerhard Feix : The big ear of Paris. Cases of the Sûreté . Verlag Das Neue Berlin, Berlin 1979.

- Dominique Kalifa: Naissance de la police privée. Détectives et agences de recherches en France, 1832–1942 (Civilizations et Mentalitès). Plon, Paris 2000, ISBN 2-259-18291-7 .

- Paul Metzner: Crescendo of the Virtuoso. Spectacle, skill and self-promotion in Paris during the age of revolution . University of California Press, Berkeley, Cal. 1998, ISBN 0-520-20684-3 ( ark.cdlib.org ).

- Jürgen Thorwald : Paths and adventures in criminology . Droemer Knaur, Munich 1981, ISBN 3-85886-092-1 (former title: The Century of Detectives ).

About Vidocq's impact on literature

- Paul Gerhard Buchloh , Jens P. Becker: The detective novel. Studies of the history and form of English and American detective literature . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1978, ISBN 3-534-05379-6 .

- Sandra Engelhardt: The investigators of crime in literature . Tectum Verlag, Marburg 2003, ISBN 3-8288-8560-8 .

- Régis Messac: Le "Detective Novel" et l'influence de la pensée scientifique . New edition: Les Belles Lettres, coll.Travaux , Paris 2011, ISBN 978-2-251-74246-5 (reprint of the Paris 1929 edition).

- Alma E. Murch: The development of the detective novel . P. Owen, London 1968.

- Charles J. Rzepka: Detective Fiction . Polity Press, Cambridge 2005, ISBN 0-7456-2941-5 .

- Ellen Schwarz: The fantastic detective novel. Investigation of parallels between “roman policier”, “conte fantastique” and “gothic novel” . Tectum Verlag, Marburg 2001, ISBN 3-8288-8245-5 (plus dissertation, University of Giessen 2001).

- Julian Symons : Bloody Murder. From the Detective Story to the Crime Novel; a history . Pan Books, London 1994, ISBN 0-330-33303-8 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Eugène François Vidocq in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Eugène François Vidocq in the German Digital Library

- Works by Vidocq in Project Gutenberg ( currently usually not available for users from Germany )

- Vidocq - Du Bagne à la Police de Sûreté (French)

- Vidocq. In: Arras-Online.com (Arras counts Vidocq asone of the city's most famous sons,along with Maximilien de Robespierre, who was born 17 years earlier; French)

- The Vidocq Society deals with long unsolved and complex crimes. The members are specialists from numerous areas of forensics (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jay A. Siegel: Forensic Science: The Basics. CRC Press, 2006, ISBN 0-8493-2132-8 , p. 12.

- ↑ James Andrew Conser, Gregory D. Russell: Law Enforcement in the United States. Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2005, ISBN 0-7637-8352-8 , p. 39.

- ↑ Clive Emsley, Haia Shpayer-Makov: Police Detectives in History, 1750-1950. Ashgate Publishing, 2006, ISBN 0-7546-3948-7 , p. 3.

- ↑ Mitchel P. Roth: Historical Dictionary of Law Enforcement. Greenwood Press, 2001, ISBN 0-313-30560-9 , p. 372.

- ↑ Hans-Otto Hügel: examining magistrate, thief catcher, detectives. Metzler, 1978, ISBN 3-476-00383-3 , p. 17.

- ↑ a b James Morton: The First Detective: The Life and Revolutionary Times of Vidocq: Criminal, Spy and Private Eye

- ^ Samuel Edwards: The Vidocq Dossier. Houghton Mifflin, Boston 1977.

- ^ Jean Savant: La vie aventureuse de Vidocq. Libraire Hachette 1957

- ^ John Philip Stead: Vidocq: A Biography. 4th edition. Staples Press, London 1954, p. 247.

- ↑ Finest of the Finest . Time.com (accessed September 9, 2007)

- ^ Alfred Eustace Parker: The Berkeley Police Story. Thomas, Springfield 1972, p. 53.

- ^ Athan G. Theoharis: The FBI. A Comprehensive Reference Guide. Oryx, Phoenix 1999, ISBN 0-89774-991-X , pp. 265f.

- ^ Charles J. Rzepka: Detective Fiction. Chapter 3 - From Rogues to Ratiocination

- ^ Hermann Melville: Schools and Schoolmasters . at the English-language Wikisource

- ↑ La Jeunesse de Vidocq ou Comment on devient policier (1909) in the IMDb

- ^ L'Évasion de Vidocq (1910) in the IMDb

- ^ Vidocq (1911) in the IMDb

- ^ Vidocq (1922) in the IMDb

- ↑ Vidocq (1938) in the IMDb

- ^ A Scandal in Paris (1946) in the IMDb

- ↑ Le Cavalier de Croix-Mort (1947) in the IMDb

- ^ Vidocq (1967) in the IMDb

- ↑ Les Nouvelles Aventures de Vidocq (1971) in the IMDb

- ↑ Vidocq - Ruler of the Underworld at Filmstarts.de , accessed May 27, 2019

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Vidocq, Eugène François |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French criminal, founder of modern criminalistics |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 23, 1775 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Arras |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 11, 1857 |

| Place of death | Paris |