Freiburg Minster

The Freiburg Cathedral (or Cathedral of Our Lady ) is in the Romanesque style , begun and largely in the style of Gothic and late Gothic consummate Roman Catholic parish church of Freiburg . It was built from around 1200 to 1513. Since Freiburg became a bishopric ( Archdiocese of Freiburg ) in 1827 , the church is formally a cathedral today , but is traditionally referred to as " Münster " and not as "cathedral". The Münster parish belongs to the pastoral care unit Freiburg Mitte in the dean's office in Freiburg .

In 1869, the art historian Jacob Burckhardt said in a lecture series about the 116 meter high tower in comparison with Basel and Strasbourg : And Freiburg will probably remain the most beautiful tower on earth . From this the often heard, but not quite literal quote about the most beautiful tower in Christianity developed . Art historians from all over the world praise the Freiburg Minster of Our Lady with the prominent west tower as an architectural masterpiece of the Gothic.

history

Building history

The first Freiburg church building, the "Konradinische" church, named after the city founder Konrad I von Zähringen , came from the founding phase of the city around 1120–1140. Only remains of the foundation remain from this first building .

While the Zähringen dukes were traditionally buried in the St. Peter monastery founded by Berthold II of Zähringen (1078–1111) in the Black Forest , Berthold V († 1218) wanted to create an appropriate burial place in Freiburg. In place of the Konradin parish church from 1120/30, a collegiate church in the late Romanesque style was to emerge based on the model of the Basel Minster . It is likely that the new church, begun around 1200, was planned as a gallery basilica with a double tower facade ; the openings of the galleries are still visible today on the west wall of the crossing . From these late Romanesque beginnings, the transept and the basement of the side towers, the so-called "Hahnentürme", have been preserved, which were topped up with openwork spiers during the Gothic construction phase.

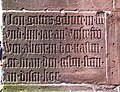

From around 1230, construction continued in the new French Gothic style with the nave and the dominant west tower. This was completed as early as 1330 and has the earliest Gothic tracery turret helmet . The city council then decided to replace the late Romanesque choir with a much larger choir with an ambulatory and chapel wreath, and commissioned Johann von Gmünd to carry out the work. An inscription on the north portal announces the laying of the foundation stone on March 24, 1354: From the birth of god MCCCLIIII jar to our frowen evening in the uasten, the first stone was laid at disen kor , but the construction of the minster hardly made any progress from around 1375/80 to 1471, so that the city council complained in 1475: we have a choir that cosstlich rheppt before zydten from our front and by a hundred years has confessed unußbuven . The vault of the new choir was not closed until 1510 (date in the choir vault): Ludwigck Horneck von Hornberg bricked up the last stone in the vault, got syß praised . The consecration of the new cathedral choir was carried out by the Constance Auxiliary Bishop on December 5, 1513, after the Constance Bishop Hugo von Hohenlandenberg had already celebrated an "intermediate consecration" in the presence of King Maximilian on the occasion of the Diet of Freiburg in 1498 . The king donated stained glass for the choir to take care of his personal life . The chapel wreath of the high choir could not be completed until 1536, marking the completion of the cathedral building. Later additions were occasionally added, for example the Renaissance vestibule on the south facade of the Romanesque transept in the 16th century and the supporting strut attachments around the high choir in the 19th and 20th centuries, which are not necessary for statics.

While the building is still referred to as a parish church ("ecclesia parochialis") in a Latin document dated May 27, 1298, the name "Münster" appears for the first time on December 24, 1356 in a document from the Countess Palatine Klara von Tübingen , daughter of the 9 Count Friedrich von Freiburg, who died November 1356 : "zuo Friburg in the minster" . So the name that had become the name of large churches was taken over for the Gothic extension.

The cathedral as an outstanding architectural monument of the city was depicted again and again in the fine arts, for the first time in the Margarita philosophica by Gregor Reisch (1504) and then especially in the Cosmographia by Sebastian Münster (1549), on the two Freiburg views of Gregorius Sickinger (1589), in the Thesaurus philopoliticus by Daniel Meisner and Eberhard Kieser (1623) and in the Topographia Germaniae by Matthäus Merian (1644). Subsequently, the number of graphic representations and paintings with the motif of the minster became unmanageable.

The minster remained largely undestroyed during World War II , although the surrounding buildings had been reduced to rubble by the bombing of November 27, 1944 by the Royal Air Force. Only the roof was damaged, but with the support of the Berlin army services, the Basel monument conservator and young people from the Münster parish, it was completely closed again by winter 1945/46. The medieval stained glass windows were also preserved because they were relocated in time for the bombing raids. Further windows and stone figures, which were replaced with restored copies in the building, can be seen in the Augustinian Museum in Freiburg .

In 2011 the exterior lighting of the minster was switched to LED . As part of the “Communities in a new light” competition, the Federal Ministry of Education and Research paid the costs of 750,000 euros. However, the lamps were too weak and fragile. Therefore, they were exchanged again at the beginning of 2017 for 330,000 euros.

In 2018, the city acquired a previously unknown medieval architectural drawing of the cathedral tower from a British art dealer. The drawing comes from a time, around 100 years after the tower was completed, when the cathedral was not being built. In addition, the present portal vestibule cannot be seen on it, but a different figure hall. The drawing will later be on view in the Augustinian Museum, but only two hours a week because of its sensitivity to light.

Legal situation

In terms of the legal situation, the Freiburg Minster is a specialty. From the beginning, the cathedral did not belong to the church.

The Zähringer Berthold V. initiated the construction of today's minster around 1200. As patron saint and main financier, the cathedral was subordinate to him. After the death of the founder, rights and obligations were initially transferred to his heirs, the Counts of Freiburg . But after the counts no longer fulfilled their obligations from the middle of the 13th century due to a lack of money, the citizens took over responsibility for building the cathedral and set up many foundations. In 1295 there was the first reference to the cathedral factory fund. The “ fabrica ecclesiae ” itself is mentioned for the first time in 1314: this legal institution encompasses the cathedral building and the fund intended for its maintenance. This "fabrica ecclesiae" was subordinate to the city council, which appointed minster caretakers who, with a large number of employees, ensured the new buildings, renovations and repairs.

In 1464 the Münster parish became a benefice of the university founded by the Habsburgs in 1457 . However, this did not mean that the assets of the Münsterfabrik were included - it remained independent and was still subject to construction.

The transfer of the city of Freiburg to the Grand Duchy of Baden in 1805 brought about a new legal situation. The entire church property was placed under state administration. In 1813 the university's patronage was canceled.

After the archbishopric of Freiburg was founded in 1821/27 and the cathedral was elevated to the status of cathedral of the archbishop of Freiburg, a new legal situation arose. In addition to the cathedral factory fund, the cathedral factory fund has existed since then, which is primarily responsible for the needs of cathedral services. The responsibilities are exactly divided, so the two institutions are not seen in a mixed bag.

The question of ownership was finally settled in 1901 in a contract between the city of Freiburg, the Archbishop's Ordinariate and the Catholic Foundation Council of the Münster parish. The minster therefore belongs to the minster factory fund and it is also responsible for building construction. The city has been granted some usage rights to the tower (e.g. ringing the bells on New Year's Day, etc.) and the square.

The Freiburg Minster Construction Association , established in 1890 out of the urgent need to renovate the minster, operates the minster construction hut and is responsible for the maintenance of the exterior of the minster. He does not own the building. The cathedral factory fund or the cathedral factory fund is responsible for the interior, the vestibule, the bells and the organ. This division of labor was established in 1891 by a decree of the Archbishop's Ordinariate and continues to this day.

architecture

Longhouse

The new construction of the minster began around 1200 in a late Romanesque architectural style. The oldest construction phases still preserved from this time are in the eastern part of the minster. The original plans envisaged a Romanesque three-aisled church with a transept and a polygonal choir. The re-planning of the nave took place around 1220 to 1230 - at a time when the architectural style on the Upper Rhine was changing from late Romanesque to early Gothic. This development was shaped on the Upper Rhine by the Strasbourg Cathedral , which set new standards in this area.

The nave has the structure typical of the High Gothic: one nave yoke corresponds to one side aisle yoke. Bundle pillars serve as load-bearing supports.

The artistic design of the east yokes was still quite modest and errors in the construction and statics of the building were certainly made in ignorance of the new architecture. Nonetheless, the importance of the Ostjoche in terms of architectural history should be emphasized, as they embody the transition from late Romanesque to high-Gothic architectural styles in the region.

The two east bays that were already standing were rebuilt from the 1930s onwards. The statics of the structure was significantly improved by raising the buttresses and using buttresses that were led over the roof and connected to the upper aisle of the central nave. The master, who completed the construction of the eastern bays, is said to have carried out the planning for the west bays of the nave and for the impressive Gothic west tower.

The four western nave bays built afterwards, which with their proportions connect seamlessly to the east bays, are characterized by a much more delicate design. Characteristic are the fine details of the forms, especially the window tracery, as well as the clear structure of the building elements, such as “plinths, bases, services with capitals”. The southern lamb portal , the design of which is based on the blind arcades on the inner west wall of the aisles, is of particular importance .

The nave was painted in the Middle Ages. When the gray paint applied in the course of the Baroque era in 1792 was removed in the 19th century, these paintings were largely destroyed. Some fragments of the medieval painting can still be seen. In 1955, a depiction of Sts. Was on the east wall of the south aisle. Martin from the 15th century detached and preserved. Today it is kept in St. Martin's Church .

tower

The striking tower of the cathedral, once referred to by the Swiss art historian Jacob Burckhardt as the “most beautiful tower on earth” (see above), is 116 meters high and offers a viewing platform at a height of 70 meters. After the completion of the 116 m high west tower around 1330, the Freiburg Minster was one of the tallest church buildings for over a century and thus also one of the tallest buildings in the world at that time. Almost at the same time, around 1333, the 123-meter-high crossing tower of Salisbury Cathedral was completed, followed by the 125-meter-high double-tower facade of St. Mary's Church in Lübeck around 1350 .

So far, a "two-master theory" had been assumed for the planning and construction history of the Freiburg cathedral tower, according to which a first conservative tower builder planned a simple, rather block-like tower and only an innovative second master made the transition to the tower octagon and above all the famous tracery turret helmet. Today, after examining the medieval tower drawings that have been preserved, the planning history of the cathedral tower is more differentiated, as the various re-plans were limited to the mezzanine floor. The crucial tower elements, however, the octagonal floor and above all the openwork tracery helmet, were part of the Freiburg planning from the start. The second in the series of preserved tower cracks can be attributed to Erwin von Steinbach's hand. This confirms the tradition written down in 1724, which ascribes the Strasbourg master an essential part of the Freiburg tower planning: “And Ervinus von Steinbach is said to have finished the cathedral in Strasbourg this year, and also made the rift to this (ie Thann) as well zu Freyburg. ”Another medieval tower crack in Freiburg was discovered in 2016.

At the foot of the tower the building is almost square in plan; the walls are massive and have almost no breakthroughs. The tower is surrounded by the twelve- sided star gallery approximately above the first third of the total height . The tower continues as an octagon above the gallery. The octagonal part merges into the so-called lantern , which is also accessible. At this height the tower has already been broken through many times; of its eight high pointed arch windows, four give a view to the outside. The also octagonal, filigree and multiple openwork spire is located above the lantern. The costal arches are covered with crabs . The tower gains its expressiveness through the architecturally perfect, playful transitions from the square to the twelve-sided to the octagonal shape in the spire to the finial on the highest point. The main building material used was sandstone , which was mainly quarried on the Lorettoberg in the Middle Ages .

It is the only Gothic church tower of this kind in Germany that was completed in the Middle Ages (around 1330) and has since survived almost miraculously, including the bombing of November 27, 1944, which destroyed the houses in the immediate vicinity of the tower . However, the building was badly affected by the vibrations. The fact that the filigree spire survived the vibrations is attributed to the iron anchors embedded in lead, which serve to connect the individual segments of the spire. The weather vane with the sun and crescent moon over the finial as the top of the tower is also unique for the period of construction ; it symbolizes the rule of Christ by day and night. There is much to suggest that the motif of this weather vane, made of fire-gilded copper sheet and renewed in 1861, was invented in Freiburg and then spread from here.

At the foot of the tower, to the left of the first portal arch, medieval dimensions (length, bread size, grain size and others) are carved (13th and 14th centuries). Attaching them to the church should give these measurements special legitimacy . An inscription also gives the dates for the two city fairs .

The tower also contains a large tower clock by Jean-Baptiste Schwilgué from 1851. It still runs, but no longer drives the pointer on the large outer dial and no longer strikes the bells. The tower also contains a Schwilgué control clock, which was installed for the tower guard in the same year .

In terms of art history, the Freiburg cathedral tower, which was completed in the Middle Ages, is of great importance as an architectural model, as it was copied in the 19th century as a model for a large number of neo-Gothic tower completions or newly built church towers. The church tower of the Mülhausen Evangelical St. Stephen's Church (97 meters), built between 1859 and 1866, is very close by . The tower of the Evangelical Reformed Church in Warsaw (built 1866–1880 by Adolf Loewe) was also modeled on the tower of the Freiburg Minster. This also served as a model for the new tower of the Lambertikirche in Münster , which was built in 1888/89 in place of an older tower that had become dilapidated.

Even Reinhold Schneider sat with his Sonnet The tower of Freiburg Minster selbigem a literary monument. It contains u. a. the line “You will not fall, my beloved tower.” What is remarkable is that Schneider wrote it months before the bombing, in which the tower was hardly damaged.

The tower helmet from February 2006 was scaffolded for renovation for twelve years. In August 2016, the scaffolding was dismantled to a third. The spire was exposed a year earlier. The work on the tower helmet was completed in May 2018. The scaffolding was then dismantled by the end of August. From 2017 to 2018 the wood in the tower and bell room was renovated. Therefore the tower was closed to visitors. After mid-August 2018, the tower could be seen again without scaffolding, except for the construction elevator on the north side. However, the scaffolding in the tower had to be dismantled. The spire couldn't support the outer scaffolding itself. After a total of 200,000 working hours, the end of this work as well as the reopening of the visitor platform and the tower room was celebrated in mid-October 2018. A zero euro note was issued on this occasion. The cleaning of the figures in the portal vestibule had also been completed by then. The redesign of the tower room was with the I NTERNATIONAL Design Award of Baden-Württemberg "Focus Special" in the Public Design / Interior Design and the Iconic Award 2019 from the German Design Council awarded.

Choir

The choir with a chapel wreath , whose characteristic spur-shaped appearance was developed from a simple geometric process, is the main work of the master builder Johann von Gmünd , who comes from the Parler family . Contrary to older research opinions, the choir was planned from the beginning with a basilical cross-section and not as a hall choir. After the long interruption in construction from around 1370 to 1471, the sections that were subsequently built were given a late Gothic look with reticulated vaults and curved tracery based on plans by the builder Hans Niesenberger and his successors. To support the completion of the choir, Pope Sixtus IV granted an indulgence , which the Freiburg theology professor Johann Pfeffer took in 1482 on the occasion of his treatise "Tractatus de materiis diversis indulgentiarum" on indulgence.

The cathedral choir has been renovated since 2014. The neo-Gothic buttress toppers had to be replaced over several decades because they crumbled and there was a risk of stone detachment. Rainwater and pollutants (pigeon droppings) have broken down the sandstone. The new pillars are made from Neckar valley red sandstone .

Furnishing

Interior

Choir room

The most important inventory is the high altar by Hans Baldung Grien. The high altar, painted from 1512 to 1516, is a winged altar that shows four Christmas pictures with the themes of the Annunciation , Visitation , Nativity and Flight into Egypt during the Christmas season . The rest of the year you can see the coronation of Mary in the middle , surrounded by the twelve apostles , six each on a folding wing, with Peter and Paul clearly in the foreground on one of the wings. The crucifixion of Christ is painted on the back, which can only be seen when visiting the chapel wreath. Here Hans Baldung portrayed himself in one of the farmhands.

Since 2003, during Lent , the choir has been draped again with the Lenten cloth from 1612, which hides the high altar behind it. This 1014 × 1225 cm, the largest surviving piece of this type in Europe, has been restored and provided with a supporting fabric . It weighs over a ton .

In the choir is the tomb of Franz Christoph von Rodt (1671–1743), a Habsburg general and commander of the Breisach Fortress, created by the sculptor Johann Christian Wentzinger between 1743 and 1745 . In the barrier system between the inner choir and the ambulatory there are four Zähringer picture plates by Franz Anton Xaver Hauser in niches framed by keel arches.

The redesign of the chancel ( altar , ambo , bishop's cathedra and choir stalls ) by the Münstertal artist Franz Gutmann , which was completed in December 2006, was controversial . The simple redesign, especially the planned removal of the altar of Anne and the Three Kings and the position of the bishopric, initially provoked violent protests from the population and the faithful. On Sunday, December 10th, 2006, Archbishop Robert Zollitsch consecrated the new altar.

Since December 2009, the oldest work of art in the cathedral has been hanging in the chancel, a late Romanesque monumental cross, the so-called Böcklin cross, which was made from oak around 1200 and covered with silver plates. It is 2.63 meters high and 1.45 meters wide and previously had its place in one of the choir chapels. Originally the cross, possibly donated by Duke Berthold V , was hung as a triumphal cross with reference to the duke's grave, as indicated by the remains of a hanging device on the cross.

Chapel wreath

A chapel wreath with eleven chapels is arranged around the high choir , most of which are named after the founder families and some of them contain high-ranking works of art. These are (from south to north): The Stürtzel Chapel with the Holy Helper altar and a baptismal font by Joseph Hörr (basin) and Anton Xaver Hauser (cover with Anabaptist group) based on a design or model by Wentzinger (1768), the university chapel with the side wings of one Altars created for the Basel Charterhouse by Hans Holbein the Younger (1525–28, Oberried Altar), the Lichtenfels-Krozingen Chapel with the Annunciation altar from 1615, the Schnewlin Chapel with the Schnewlin Altar created in 1515 by Hans Wydyz (group of figures "Rest on der Flucht ”) and a pupil Hans Baldung Griens (wing). The southern and northern imperial chapels are arranged at the apex of the choir; From here you can see the back of the high altar by Hans Baldung, with a crucifixion, the town and university patrons and the cathedral caretakers and conductors who organized and supervised the construction. This is followed by the Villinger-Böcklin Chapel, the Sother Chapel with an altar from around 1500, the Locherer Chapel with an altar by Hans Sixt von Staufen (1521–1524) showing a Madonna in a protective cloak, and finally the Blumenegg Chapel.

window

The stained glass windows come from all the construction periods of the cathedral. In the Romanesque transept you can see stained glass windows from this construction period (around 1220–1260). Most of the Gothic windows in the nave were donated by the craft guilds , as indicated by symbols such as pretzels, boots, etc. (around 1330). Emperor Maximilian donated the so-called imperial windows in the high choir. After the Gothic construction period, a number of the medieval windows were removed because - in keeping with the times - they wanted more light in the church. As a result, some of the valuable stained glass were irretrievably lost. Around 1900 the glass artist Fritz Geiges took care of the preservation and restoration of the windows on behalf of the Freiburg Minster Association, but with results that experts criticized already at the time. In addition to good copies that replace the originals, some of which are in the museum, in the Münster today, he also added missing parts in existing windows or brought their motifs into new contexts. Geiges provided additions to medieval windows with artificial aging in order to imitate lost parts. He also created new "medieval" windows in the historicizing style of his time. The windows of the minster were removed during the Second World War. They were therefore not exposed to the air pressure and fragments during the bombing raid on November 27, 1944 and were preserved.

The restoration of the Peter and Paul Chapel in 2017/18 in the northern transept of the Freiburg Minster contains only part of the original glazing of the chapel (around 1345/50). The medieval glazing was expanded in the 19th century. Here, too, Fritz Geiges reinserted the upper figure fields and the tracery panes with the addition of reconstructions.

The west window in the Michael's Chapel and the south rosette by Valentin Peter Feuerstein date from the 20th century . The Freiburg artist Hans-Günther van Look created a window showing Edith Stein at the beginning of the 21st century and designed six medallions with "holy women" in the round window of the south transept, which corresponded to the medallions in the opposite "window of mercy" correspond from the Middle Ages.

Rood screen

In 1579 Hans Beringer was commissioned to create a new rood screen, which was removed in 1790 and rebuilt as a music tribune in the transepts.

Portal porch

The Gothic portal hall of the west tower (around 1300) shows a representation of the Last Judgment in the tympanum , which is expanded to include scenes from the life of Jesus (birth and passion). The focus is on Christ as a merciful judge. The archivolts show important figures of the Old Covenant and thus point to the continuity of the Old and New Testaments. The portal wall is occupied by a cycle of Mary, in the center of which there is a magnificent representation of the Virgin Mary in front of the pillar of the portal. The sculptures of the five foolish and five wise virgins , as they are presented in terms of motif and style on the Strasbourg cathedral, are also part of the rich figural decoration of the vestibule . They are supplemented by a depiction of the prince of the world , who, as a tempter, should be particularly noticeable as a warning to the believer leaving the church. During the renovation and cleaning of the figures, the state of the previous renovation from the 1990s was consciously restored, for which the Freiburg glass painter and artist Fritz Geiges was responsible at the time. In 2018 the figures were cleaned again.

City cartridge

Inside and on the exterior of the Freiburg Minster, but also on the Münsterplatz as well as in the city's museums and archives, there are still numerous depictions of the city's patron saint : St. George, Bishop Lambert of Liège and the catacomb saint and martyr Alexander, George ab superseded representations in the 17th century. Examples of the knight Georg as the city's oldest patron can be found on one of the south-west buttresses of the cathedral and on the Georgsbrunnen in the south-west corner of the Münsterplatz. In addition, the town patrons Ritter Georg and Bishop Lambert - with the Madonna as the cathedral patroness - are shown at the fish fountain in front of the Kornhaus on the northwest side of the Münsterplatz, here together with the four church teachers . Not only is the large number of depictions as sculptures and goldsmiths' work, on paintings and glass windows, woodcuts and copperplate engravings, but also the fact that some depictions were created by important artists, including Hans Baldung Grien (St. George on the back of the high altar ). Also on the so-called patronage columns in front of the main portal are statues of the city patron Lambert and Alexander with the Virgin Mary as patroness of the cathedral in the middle. These three figure columns were donated in 1719 by the three United States of the Upper Austria : the prelate , the knight and the collegiate of the Breisgau cities of Freiburg im Breisgau , Altbreisach , Neuenburg am Rhein and Waldshut and have been restored several times since then, most recently in 2016/2017. The figure of Lambertus had to be completely redone.

Cameras and screens

Since 2013, the cathedral has been equipped with five permanently installed cameras. Since then, selected church services have been broadcast both on the Internet and via two screens in each of the aisles. The Archdiocese has invested a six-figure sum in the technology, which also includes a control room in the tower with four large screens, a control unit and a mixer for the sound. There are also text overlays such as B. the song numbers. In 2018, the archbishopric stopped the live broadcast for a few months due to the new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the resulting law on church data protection (KDG). After a solution had been found, namely to inform the worshipers about the broadcast, the broadcast could be resumed on Assumption 2018.

Since August 2018 there have been ten more cameras in the Münster, which, together with the TV cameras, serve to secure evidence in the event of theft and damage to property. The closed system was expanded for 5000 euros. The recordings are kept for 48 hours and are only accessible to a few employees. There were two major thefts. While the heraldic cartouche of the Lambertus column in front of the minster, stolen in 2017, reappeared, an almost 200-year-old figure of the Apostle Paul from the St. Anne's Altar has been missing since 2018.

Organs

The Freiburg Minster is also known for its organ system . The four-part system, consisting of the Marien organ in the north transept, the Langschif organ ( swallow's nest organ ), the Michael’s organ on the gallery under the tower (Michael’s chapel) and the choir organ, is one of the largest organs in Germany and the world with 144 stops on four manuals and pedal . The organs come from various organ builders ( Rieger , Marcussen , Späth and Fischer & Krämer ) from 1964 to 1966, partially renewed and rebuilt in 1990 and 2001. At the end of 2008, the Michael’s organ was replaced by a new one by the organ builder Metzler from Dietikon near Zurich. Another phase of renovation began in 2017, initially with the St. Mary's Organ. This was followed by a new construction of the choir organ, which sounded for the first time at Easter 2019.

Bells

The cathedral bell consists of 19 bells . With a total weight of around 25 tons, the Freiburg cathedral bell is one of the largest cathedral bell rings in Germany.

The oldest bell in the ring is the Hosanna from 1258, which is also one of the oldest surviving bells of this size. According to the foundation, it is held on Thursday evenings after the Angelus to commemorate Christ's agony on the Mount of Olives, on Fridays at eleven o'clock to commemorate the crucifixion of Christ (popularly also Knöpfleglocke - then it was supposedly time to put the water on for the Knöpfle , a spaetzle variant ), on Saturday evenings in prayer for the dead of the week and on November 27th, the anniversary of the bombing and destruction of the city in 1944. In the past it was also used as the fire and storm bell and was rung to call a court assembly. The inscription on the bell reads:

- ANNO DOMINI M C C L VII I XV KLAS AVGVSTI STRVCTA EST CAMPANA - O REX GLORIE VENI CVM PACE - ME RESONANTE PIA POPVLO SVCVRRE MARIA

- (The bell was poured on July 18, 1258. - O King of Glory, come in peace. - If I sound pious, rush to the aid of the people, Mary).

The late medieval baptismal bell hangs in the roof turret above the south transept . Until 1841/43, for almost 600 years, the Hosanna was the largest bell in the minster. During these years, a new bell in line with contemporary tastes was cast by the Rosenlächer bell foundry from Constance. The ten bells had the tones b 0 , d 1 , f 1 , gb 1 , a 1 , b 1 , des 2 , d 2 , f 2 and b 2 . Since then, the hosanna has only been rung individually, as it was a quarter tone too low in contrast to the mood of the other bells. The festive bells consisted of the tones b 0 , d 1 , f 1 , g 1 and b 1 ; the g 1 bell was added in 1950.

Although the bells that were hung before the war had survived the bombing raids and had not been forced to be melted down, Friedrich Wilhelm Schilling cast 15 new bells for the west tower in Heidelberg in 1959. Johannes Wittekind, head of the bell inspection of the Archdiocese of Freiburg, says that those responsible for the diocese paid homage to a “new view of bell music” after the war. Back then, people “wanted away from the chordal and towards more melodic sounds”. The Hosanna, now the third largest bell, was rung individually. In 2008, after six years of work, the renovation of the belfry, the oldest of which was made of fir wood, was completed in 1290/91. As a result of the redistribution of the bells, the Hosanna , whose 750th anniversary was celebrated in the same year, can also be rung together with the other bells. The vesper bell, cast in 1606, and the silver bell from the 13th century were also hung in the west tower so that they could be rung after a successful restoration. In 2017–2018 the belfry was restored again.

In 2016, 15 new clappers were forged by the company Edelstahl Rosswag in Pfinztal for the bells, which were replaced in December 2016.

| No. |

Surname |

Casting year |

Foundry, casting location |

Diameter (mm) |

Mass (kg) |

Chime |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Christ | 1959 | Friedrich Wilhelm Schilling, Heidelberg |

2133 | 6856 | g 0 |

| 2 | Peter | 1774 | 3917 | b 0 | ||

| 3 | Paul | 1566 | 2644 | c 1 | ||

| 4th | Maria | 1490 | 2290 | d 1 | ||

| 5 | Hosanna | 1258 | anonymous | 1610 | 3290 | it 1 |

| 6th | Joseph | 1959 | Friedrich Wilhelm Schilling, Heidelberg |

1242 | 1354 | f 1 |

| 7th | Nicholas | 1095 | 958 | g 1 | ||

| 8th | John | 1081 | 913 | a 1 | ||

| 9 | James | 1022 | 803 | b 1 | ||

| 10 | Konrad | 903 | 560 | c 2 | ||

| 11 | Bernhard | 798 | 381 | d 2 | ||

| 12 | Lambert and Alexander | 670 | 212 | f 2 | ||

| 13 | Michael | 594 | 149 | g 2 | ||

| 14th | Guardian Angel | 575 | 130 | a 2 | ||

| 15th | Odilia | 505 | 112 | c 3 | ||

| 16 | Magnificat | 456 | 79 | d 3 | ||

| 17th | Vesper bells | 1606 | Hans Ulrich Bintzlin, Breisach | 510 | 70 | h 2 |

| 18th | Silver bells | 13th century | anonymous | 352 | 33 | f 3 |

| 19th | Baptismal bell | 13./14. Century | anonymous | 550 | 95 | a 2 |

Monument preservation

Towards the end of the 19th century, the ominous state of construction of the Freiburg Minster was not hidden from the city of Freiburg and its citizens, but at the same time personal commitment to the Minster and the financial donations from Freiburg had reached a low point. An expert commission officially determined the damage in 1889.

Since the then owner of the Freiburg minster - the minster factory, a medieval foundation - could not raise the financial means, Lord Mayor Otto Winterer made an urgent appeal to the citizens to found an association to save the minster. Winterer deliberately countered the increased call for church funding and the public sector to maintain the building with the idea of a development association. In 1890, the Freiburg Minster Building Association was founded to preserve the minster . The association has to raise several million euros a year to secure and maintain the Freiburg Cathedral. The current cathedral builder is the architect Yvonne Faller. The chairman of the association is Sven von Ungern-Sternberg .

Since 2011 there has been a project to extract stones for restoration from a reopened quarry near Emmendingen , near the former Tennenbach monastery . The stones for building the cathedral came from there in the Middle Ages.

Physics in the Freiburg Minster

Two brass points are embedded in the floor below the bell tower. From a geometrical point of view, the larger one is located directly vertically below the top of the bell tower. The smaller point is where an object would hit if dropped directly from the top of the tower. The difference between the geometric point and the point of impact is a consequence of the earth's rotation , with Coriolis force (deflection to the east) and centrifugal force (deflection to the south) acting on the falling body. At about 3.2 centimeters, the specified difference is too large compared to the result of an exact calculation (1.84 centimeters).

various

In 2019 the archdiocese spread the April Fool's joke that an old brook had been exposed in the cathedral .

The west tower of the minster (view from the west) is depicted on the right of the commemorative coin 900 years of Freiburg .

literature

Specialist literature

Periodicals

- Münsterbauverein Freiburg i. Br. (Ed.): Freiburg Cathedral Papers. Half-year publication for the history and art of the Freiburg Minster , Vol. 1–15, Freiburg 1905–1919.

- Münsterblatt. Annual publication of the Freiburg Minster Association. Vol. 1, 1994 ff. (Appears once a year)

- Books and essays

- Friedrich Kempf (architect) | Friedrich Kempf: The Freiburg Minster. His building and art maintenance . In: Badische home 1, 1914, pp 1-88, ( Digitalisat the UB Heidelberg ).

- Friedrich Kempf: The Freiburg Minster . Braun, Karlsruhe 1926.

- Hans Jantzen : The Münster to Freiburg . Verlag August Hopfer, Burg near Magdeburg 1929.

- Fritz Geiges : The medieval window decorations of the Freiburg Minster. Its history, the causes of its disintegration and the measures taken to restore it; at the same time a contribution to the history of the building itself . Freiburg 1931/33, ( digitized version ).

- Volker Osteneck: The Romanesque components of the Freiburg Minster and their stylistic prerequisites . Hanstein, Cologne / Bonn 1973.

- Anton Legner (ed.): The Parler and the beautiful style 1350-1400 . Cologne 1978. Volume 1, pp. 293-302.

- Ingeborg Krummer-Schroth : Glass paintings from the Freiburg Minster . Rombach, Freiburg 1967; 2nd edition 1978.

- Reinhard Liess : The Rahnsche Riss A of the Freiburg cathedral tower and its Strasbourg origin . In: Journal of the German Association for Art Science 45, Issue 1/2, 1991, pp. 7–66.

- Wolf Hart, Ernst Adam: The artistic equipment of the Freiburg Minster. Rombach, Freiburg 1981, ISBN 3-7930-0269-1 ; 2nd Edition. Freiburg 1999.

- Wolf Hart: The sculptures of the Freiburg Minster. Rombach, Freiburg 1975; 3rd edition Freiburg 1999.

- Wolf Hart, Ernst Adam: The Freiburg Minster . Rombach, Freiburg i. Br. 1978, ISBN 3-7930-0311-6 ; 2nd edition 1999.

- Rüdiger Becksmann: To secure and restore the medieval stained glass in the Freiburg Minster. In: Denkmalpflege in Baden-Württemberg 1980, 9th year, issue 1, pp. 1–6, ( digitized UB Heidelberg).

- Georg Schelbert: To the beginnings of the Gothic choir of the Freiburg Minster. New observations on the sacristy and Alexander chapel. In: architectura 26 (1996), pp. 125–143, ( digital copy from Heidelberg University Library).

- Heike Köster: The gargoyles on Freiburg Cathedral . Edited by the Freiburg Minster Construction Association. Kunstverlag Fink, Lindenberg 1997, ISBN 978-3-931820-43-5 .

- Thomas Flum: The late Gothic choir of the Freiburg Minster. Building history and structure. Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, Berlin 2001, ISBN 978-3-87157-189-3 , ( dissertation from the University of Freiburg ).

- Thomas HT Wieners: Self-Representation on the Way to Salvation. Church foundations using the example of the Freiburg Minster. In: Sönke Lorenz , Thomas Zotz (Hrsg.): Late Middle Ages on the Upper Rhine. Everyday life, crafts and trade 1350–1525. Part 2. Jan Thorbecke Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, pp. 465-472, ISBN 978-3-7995-0208-5 .

- Markus Aronica: From the devil to the judge of the world - an introduction to the image program of the portal hall in the Freiburg cathedral tower . Promo-Verlag, Freiburg i. Br. 2004; 3rd edition 2010, ISBN 978-3-923288-74-8 .

- Wolfgang Hug : Beautiful women from the Freiburg Minster. Portraits from eight centuries . Herder, Freiburg i. Br. 2004, ISBN 978-3-451-28311-6 .

- Dagmar Zimdars (Red.): “Noble folds, painted adventurously ...” The tower porch of the Freiburg Minster - investigation and preservation of the polychromy . Published by the Baden-Württemberg State Monuments Office . Theiss, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 978-3-8062-1944-9 , table of contents.

- Heike Mittmann: The stained glass windows of the Freiburg Minster . Edited by the Freiburg Minster Construction Association. Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 2005, ISBN 978-3-7954-1717-8 .

- Rüdiger Becksmann : The medieval glass paintings in Freiburg i. Br. (= Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi , Germany II, 2.) Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-87157-226-5 .

- Yvonne Faller, Heike Mittmann, Stephanie Zumbrink, Wolfgang Stopfel: The Freiburg Minster. Edited by the Freiburg Minster Construction Association. Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-7954-1685-0 .

- Guido Linke: Freiburg Cathedral: Gothic sculptures in the tower porch . Edited by the Freiburg Minster Construction Association. Rombach, Freiburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-7930-5082-7 .

- Heike Mittmann: Freiburg Minster: The choir chapels - history and furnishings. Rombach, Freiburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7930-5102-2 , table of contents.

- Michael Bachmann : The Freiburg Minster and its Jews. Historical, iconographic and hermeneutic observations . Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2017, ISBN 978-3-7954-3262-1 .

Art and church guides

- Friedrich Kempf, Karl Schuster : The Freiburg Cathedral. A guide for locals and foreigners . Herder, Freiburg 1906, ( digitized from Heidelberg University Library).

- Josef Marmon : Our dear women Münster zu Freiburg im Breisgau , 1878, digitized from Google books .

- Julius Baum : Twelve German cathedrals from the Middle Ages . Atlantis Verlag, Zurich 1955.

- Ernst Adam: The Freiburg Minster. Müller and Schindler, Stuttgart 1968; 3rd edition 1981.

- Konrad Kunze : Heaven in stone. The Freiburg Minster. The meaning of medieval church buildings. Herder, Freiburg 1980; 14th edition 2014, ISBN 978-3-451-33409-2 .

- Wolfgang Hug : The Freiburg Minster. Art - history - world of belief. 2nd Edition. Buchheim-Druck, March-Buchheim 1995, ISBN 3-924870-06-3 .

- Hermann Gombert : The Minster of Freiburg im Breisgau. 5th edition. Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 1997, ISBN 3-7954-0593-9 .

- Peter Kalchthaler : Munster of our Dear Lady (62), Munsterplatz. In: ders., Freiburg and its buildings. An art-historical city tour. 4th edition. Promo-Verlag, Freiburg 2006, ISBN 978-3-923288-45-8 , pp. 238–248, table of contents.

- Heike Mittmann: The cathedral in Freiburg im Breisgau . Edited by the Freiburg Minster Construction Association. 9th, updated edition, Kunstverlag Josef Fink, Lindenberg 2018, ISBN 978-3-933784-26-1 .

Web links

- freiburgermuenster.info - Archbishop's Cathedral Parish Office

- Freiburg Minster Construction Association

- The organs in the Freiburg Minster

- The bells in the Freiburg Minster

- The stained glass windows in Freiburg Minster , April 2009

- Information about the minster, tower, altar, market

- Interview with the minster builder Yvonne Faller. In: Monuments Online, December 2007

- Interview with the minster builder Yvonne Faller. In: Monuments Online, October 2018

- University of Konstanz to the Holy Sepulcher Chapel (approx. 1330)

- 3D model of the Freiburg Minster

Videos

- The west tower of the Freiburg Minster. In: State Office for Monument Preservation Baden-Württemberg , March 24, 2017, 8:40 min.

- Evening show: New organ for Freiburg Cathedral. In: SWR / ARD Mediathek , November 16, 1965, 4:53 min., Accessed on May 14, 2020.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ursula Saß: "The most beautiful tower in Christendom" / "The most beautiful tower on earth" - Jacob Burckardt and the Freiburg Minster. In: Münsterblatt 2007, No. 14, p. 31.

- ^ Freiburg im Breisgau. The city and its buildings . Wikisource.

- ^ Hans W. Hubert: The Minster Bertolds V. (1186-1218), building design and level of demands in a supra-regional comparison . In: The Zähringer, rank and rule around 1200 . Conference proceedings. (= Publication by the Alemannic Institute , No. 85.) Thorbecke-Verlag, Ostfildern.

- ↑ Peter Paul Albert : Documents and Regesta on the history of the Freiburg Minster. In: Freiburger Münsterblätter 5, 1909, No. 155, p. 31.

- ↑ Freiburg City Archives, Missives 4, location 7, fol. IV., After Thomas Flum: The late Gothic choir of the Freiburg Minster. Building history and structure . Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, Berlin 2001, p. 165.

- ↑ Münster calculations, based on Thomas Flum: The late Gothic choir of the Freiburg Minster. Building history and structure . Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, Berlin 2001, p. 142.

- ^ Henrich Schreiber: The Münster to Freiburg. (= Monuments of German architecture of the Middle Ages on the Upper Rhine . Volume 2, 2). Enclosures p. 22 ( digitized version ).

- ^ A b Yvonne Faller, Stephanie Zumbrink: December 5, 1513. The new cathedral choir is consecrated. In: For year and day. Freiburg's history in the Middle Ages. Rombach, Freiburg i. Br. 2013, ISBN 978-3-7930-5100-8 , pp. 187ff.

- ^ Peter Kalchthaler: Small Freiburg city history . Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2006.

- ^ Hans Georg Wehrens: Freiburg im Breisgau 1504 - 1803. Woodcuts and copper engravings . Herder, Freiburg i. Br. 2004, pp. 23, 45, 63, 106 and 118.

- ^ Freiburg city administration: Freiburg after the war - time of need and awakening , May 13, 2014; Münsterbauverein Freiburg: History of Münsterbau: Preserving the heritage. ( Memento from September 7, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Heiko Haumann , Dagmar Rübsam, Thomas Schnabel, Gerd R. Ueberschär : Swastika over the town hall. From the dissolution of the Weimar Republic to the end of the Second World War (1930–1945). In: History of the City of Freiburg. Volume 3: From the rule of Baden to the present , Theiss, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 978-3-8062-0857-3 , p. 365.

- ↑ Photonics: Municipalities in a New Light. In: The Federal Government . July 15, 2013, accessed May 14, 2020 .

- ↑ Sina Gesell: Enlightenment: 119 new LED spotlights illuminate the cathedral at night. ( Memento from June 16, 2017 in the Internet Archive ). In: Badische Zeitung , April 14, 2017.

- ^ Frank Zimmermann: So far unknown architectural drawing of the Freiburg cathedral tower surfaced. In: Badische Zeitung. November 28, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2018 .

- ^ A b Wolf Hart: The Freiburg Minster . Rombach, Freiburg i. Br. 1978, ISBN 3-7930-0311-6 , pp. 27f.

- ^ A b c Wolf Hart: The Freiburg Minster . Rombach, Freiburg i. Br. 1978, ISBN 3-7930-0311-6 , pp. 40f.

- ^ Wolf Hart: The Freiburg Minster . Rombach, Freiburg i. Br. 1978, ISBN 3-7930-0311-6 , p. 35.

- ^ Wolf Hart: The Freiburg Minster . Rombach, Freiburg i. Br. 1978, ISBN 3-7930-0311-6 , p. 39.

- ^ A b Wolf Hart: The Freiburg Minster . Rombach, Freiburg i. Br. 1978, ISBN 3-7930-0311-6 , p. 41f.

- ^ Wolf Hart: The Freiburg Minster . Rombach, Freiburg i. Br. 1978, ISBN 3-7930-0311-6 , p. 42.

- ^ Wolf Hart: The Freiburg Minster . Rombach, Freiburg i. Br. 1978, ISBN 3-7930-0311-6 , p. 43.

- ^ The construction of the west tower (graphic: Münsterbauverein). ( Memento from July 30, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ). In: freiburgermuenster.info .

-

↑ Johann Josef Böker and Anne-Christine Brehm: The Gothic architectural drawings of the Freiburg cathedral tower . In: Freiburger Münsterbauverein (Hrsg.): The Freiburg Minster . Verlag Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 2011, pp. 323–327, ISBN 978-3-7954-1685-0 ;

Johann Josef Böker, Anne-Christine Brehm, Julian Hanschke and Jean-Sébastien Sauvé: The architecture of the Gothic: The Rhineland . Müry Salzmann Verlag, Salzburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-99014-064-2 , No. 24;

Johann Josef Böker: A newly found construction plan of the Freiburg cathedral tower . In: Insitu - Zeitschrift für Architekturgeschichte , 2018, No. 1, ISSN 1866-959X , pp. 25–36. - ↑ See also Hans W. Hubert: Gotische Bauplanung; The minster tower - plan drawings; Master Erwin and Freiburg ?; Four cracks for the cathedral tower , in: Baustelle Gotik. The Freiburg Minster . Catalog Augustinermuseum, Petersberg 2013, pp. 110–117.

- ↑ Annales or annual stories of the Baarfüseren zu Thann etc. by Malachias Tschamser 1724 . Kolmar 1864.

- ^ Johann Josef Böker: A newly found construction plan of the Freiburg cathedral tower. In: Insitu - Journal for Architectural History 10, 2018.

- ^ Konrad Kunze: Heaven in Stone - The Freiburg Minster . 13th edition, Herder, Freiburg i. Br. 2007, ISBN 978-3-451-33409-2 , p. 26.

- ↑ Text of the funfair inscription on the southern buttress of the tower vestibule : one note will be given the next day before and one day after St. Niclaus Kilwi • and the other on the next day and week after every holy day and note one day before and one after. For further meaning see Hermann Flamm: The fair inscription in the tower porch of the Freiburg Minster. In: Freiburger Münsterblätter 6, 1910, pp. 50–51, ( digitized version of Heidelberg University Library).

- ↑ Klaus Hemmerle interprets: Reinhold Schneider, Der Turm des Freiburger Münsters. In: klaus-hemmerle.de , accessed on May 14, 2020.

- ↑ Julia Littmann: Landmark: Münsterturm renovation will take until the end of 2016. ( Memento from March 25, 2013 in the Internet Archive ). In: Badische Zeitung , February 23, 2015.

- ↑ Julia Littmann: Barrier: Dismantling of the scaffolding on the minster tower helmet much shorter than planned. ( Memento from August 19, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: Badische Zeitung , August 19, 2016.

- ↑ Joachim Röderer: Unveiled. After twelve years, the Freiburg cathedral tower will soon be without scaffolding. In: Badische Zeitung. April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018 .

- ^ A b Freiburg: Freiburg Minster: Wood is being renovated in the Minster Tower at a height of 43 meters. ( Memento from January 16, 2017 in the Internet Archive ). In: Badische Zeitung , January 13, 2017, with photo series.

- ^ Fabian Vögtle: Cathedral tower closed until autumn. Renovation of the tower room and stairwell more expensive than expected. ( Memento from January 18, 2018 in the Internet Archive ). In: Badische Zeitung , January 17, 2018.

- ↑ Joachim Röderer: After twelve years, the scaffolding on the cathedral tower will be dismantled. In: Badische Zeitung , May 29, 2018, accessed on May 14, 2020, only the beginning of the article (registration required).

- ↑ diezwei: Something else. In: Badische Zeitung. October 12, 2018, accessed October 13, 2018 .

- ↑ Dismantling the scaffolding on the spire. In: Freiburg Minster Construction Association. Retrieved May 14, 2020 .

- ↑ Anika Maldacker: The scaffolding of the cathedral tower is loose - after twelve years. In: Badische Zeitung. August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 25, 2018 . Only beginning of article (registration required).

- ^ BZ editorial team: Award for the design of Freiburg's highest workplace. ( Memento of November 13, 2019 in the Internet Archive ). In: Badische Zeitung , November 13, 2019.

- ^ Georg Schelbert: To the beginnings of the Gothic choir of the Freiburg Minster. New observations on the sacristy and Alexander chapel. In: architectura 26, 1996, pp. 125–143, ( digital copy from Heidelberg University Library); Thomas Flum: The late Gothic choir of the Freiburg Minster. Building history and structure. Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, Berlin 2001, pp. 18–38.

- ^ Anne-Christine Brehm: Hans Niesenberger of Graz. A late Gothic architect on the Upper Rhine. Schwabe, Basel 2013; Thomas Flum: The late Gothic choir of the Freiburg Minster. Building history and structure. Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, Berlin 2001, pp. 47–84.

- ^ Johann Pfeffer : Tractatus de materiis diversis indulgentiarum , Basel 1482, ( digitized version of the TU Darmstadt ).

- ↑ "Another 500 Years". The late Gothic cathedral high choir is being renovated. ( Memento of March 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: Badische Zeitung , July 4, 2015, with a photo gallery of the construction site , photos by Michael Bamberger and Paula Kowaltschik.

- ↑ Fridolin Keck (Ed.): The Freiburg Fastentuch 1612–2012. Herder, Freiburg i. Br. 2012, ISBN 978-3-451-30589-4 .

- ^ Rudolf Reinhardt : Maximilian Christoph v. Rodt. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 16, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-428-00197-4 , p. 506 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Karl Schmid, Hans Schadek (Ed.): Die Zähringer. Volume 2: Impulse and Effect. Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1986, ISBN 3-7995-7041-1 , p. 219.

- ^ Cathedral chapter and cathedral parish Freiburg (ed.): Identity in Transition - The redesign of the sanctuary in the Cathedral of Our Lady of Freiburg . Kunstverlag Fink, Lindenberg 2007, ISBN 978-3-89870-407-6 .

- ^ Rolf-Dieter Blumer, Daniela Straub, Dagmar Zimdars: Restored and hung. The Freiburg Böcklinkreuz. In: Preservation of monuments in Baden-Württemberg. 39th year 2010, issue 2, pp. 67-72 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Karl Schuster: On the building history of the Freiburg Minster in the 18th century In: Freiburger Münsterblätter. 5, 1909, p. 6 ( digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de ).

- ↑ Sibylle Large: The Shrine and wings painting of Schnewlin-altar in the cathedral. Studies on the Baldung workshop and on Hans Leu the Elder. J. In: Journal of the German Association for Art Science 45, 1991, pp. 88–130.

- ^ Karl Schuster: The rood screen in the Freiburg cathedral. In: Freiburg Cathedral Papers. 1, 1905, pp. 45-62 ( digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de ).

- ↑ Dagmar Zimdars (Red.): "Noble folds, painted adventurously ...": the tower porch of the Freiburg Minster. Investigation and conservation of polychromy . Theiss, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8062-1944-3 .

- ^ Hans Georg Wehrens: The city patron of Freiburg im Breisgau . In: Journal of the Breisgau history association “Schau-ins-Land” 126, 2007, pp. 39–68 ( dl.ub.uni-freiburg.de ) with addendum 130, 2011, pp. 67–69; Hans Georg Wehrens: The city patron of Freiburg im Breisgau . Promo Verlag, Freiburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-923288-60-1 .

- ↑ Hans Georg Wehrens: The three patronage columns in front of the main portal of the Freiburg Minster . In: Münsterblatt - annual publication of the Freiburger Münsterbauverein eV , No. 23, 2016, pp. 5–18.

- ↑ JVx: cathedral minister Wolfgang Gaber has blessed the patronage columns. In: Badische Zeitung. July 11, 2017. Retrieved July 11, 2017 .

- ↑ Text & Video: Joachim Röderer: Freiburger Münster-TV goes on air - Gänswein live. In: Badische Zeitung. August 15, 2013, accessed August 12, 2018 . Only beginning of article (registration required).

- ↑ Joachim Röderer: Archdiocese stops live streams from the Freiburg Minster - because of data protection. In: Badische Zeitung. May 25, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018 .

- ↑ KNA : concerns dispelled: Archdiocese of Freiburg is streaming again from the minster. In: Badische Zeitung. August 2, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018 .

- ↑ Archbishopric Freiburg is broadcasting live again. In: Archdiocese of Freiburg . August 2, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018 .

- ↑ Fabian Vögtle: The Freiburg Minster is now completely video-monitored. In: Badische Zeitung. August 9, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018 .

- ↑ Johannes Adam: Classic: A sounding feast for the eyes. In: Badische Zeitung. February 17, 2017. Retrieved February 17, 2017 .

- ↑ Johannes Adam: Quality from Switzerland: The Freiburg cathedral gets a new choir organ. In: Badische Zeitung. March 28, 2018, accessed October 20, 2018 . Only beginning of article (registration).

- ↑ Kurt Kramer : The Hosanna and the Bells of the Freiburg Minster. History and stories . Kevelaer 2008; Kurt Kramer: The bell and its ringing. 3. Edition. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 1990, p. 51, Kurt Kramer u. a .: The German bell landscapes. Baden-Hohenzollern. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 1990, p. 46.

- ^ Hosanna bell in the Freiburg Minster, inscription panel - Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved May 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Jehl: Freiburg: Wrought: All 15 bells of Freiburg Minster received new clapper. In: Badische Zeitung. August 15, 2016. Retrieved August 15, 2016 .

- ↑ New clappers for the bells. In: freiburgermuenster.info , 2016.

- ↑ organs and committees. In: Münsterbauverein Freiburg .

- ^ Marius Alexander: Emmendingen: Stones from Tennenbach for the cathedral. In: Badische Zeitung. November 21, 2012, accessed May 14, 2020 . Only beginning of article (registration required).

- ^ Jürgen Giesen: Physics and Astronomy. Freiburg Minster. In: jgiesen.de , 2016.

- ↑ News from the Münsterbächle. In: Archdiocese of Freiburg . Retrieved May 10, 2019 .

- ↑ Christopher Ziedler: 900 years of Freiburg. This is the official commemorative coin for Freiburg's city anniversary. In: Badische Zeitung , September 5, 2018, only beginning of article (registration required).

Coordinates: 47 ° 59 ′ 44 ″ N , 7 ° 51 ′ 8 ″ E