History of Mecklenburg

The history of Mecklenburg begins with the first post-glacial settlement from around 10,000 BC. A. These hunters, fishermen and gatherers were followed by rural cultures in the 4th millennium. The state of Mecklenburg was a principality until 1918 and was ruled by the same ruling family, the Obodrites , with only a two-year break from its incorporation into the Holy Roman Empire until 1918 . Today Mecklenburg forms the western two thirds of the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania .

origin of the name

The name Mecklenburg ("Mikelenburg") appears for the first time in a document from the year 995. At that time it referred to the Slavic castle Mecklenburg (Wiligrad) in today's village of Mecklenburg near Wismar and means something like large castle ( Middle Low German "mikil" or "miekel" = large ). The name was subsequently carried over to the Slavic Abodrite princes and then to the area they ruled. Colloquially, Mecklenburg in modern times was the term used to describe the sum of all partial rulers owned by the dynasty.

Prehistory and early history

Stone, bronze and iron ages

The southwest coast of the Baltic Sea was only discovered after the end of the last great ice age and the receding of the ice border between the 10th and 8th millennium BC. It was rather sparsely populated by arctic hunters and gatherers of the Paleolithic and Mesolithic . One of the important sites of the late Paleolithic (10,000 to 8,000 BC) is likely to be on the Büdneracker von Siggelkow near Parchim . In the Mesolithic (8000 to 3000 BC) the number of find places of stone tools (stone axes, pimples, scrapers, flint flakes) and bone tools in Mecklenburg increased significantly. v. a. in Hohen Viecheln , Tribsees , Plau , Neustadt-Glewe , Dobbertin .

With a significant delay compared to the Central German area, the nomads began in what was later to become Mecklenburg around 3,000 BC. Chr. To settle down . Stone tools and large stone graves , so-called " megalithic graves ", of the Neolithic funnel cup culture, have been handed down in large numbers in Mecklenburg. At the beginning of the late Neolithic , the funnel beaker culture was replaced by the individual grave culture , which belonged to the culture group of corded ceramics .

Also the Bronze Age - in Mecklenburg around 1800 to 600 BC. BC - started reluctantly in the region. Barter must have played an increasingly important role, as the base metals had to be imported for the manufacture of tools and weapons. The metal objects such as the cult car from Peckatel were imported ready-made from the southern low mountain ranges ; only in the course of the younger Bronze Age did their own bronze foundry trade develop . Within the tribes, social classes emerged, which manifest themselves in the royal tomb of Seddin or in the construction of castles .

With the beginning of the Iron Age, the funnel beaker culture went over to the Jastorf culture . Iron was first introduced until one learned to smelt the native lawn iron ore . An important burial ground of the Jastorf culture is the cremation burial ground of Mühlen Eichsen northwest of Schwerin . About 5000 dead were buried here from the sixth BC to the first century AD.

Germanic tribes

Until the last century before our era, Germanic tribes had developed from the Jastorf culture : Lombards , Warnen , Semnones and possibly also the Saxons . In the west they belonged to the group of the Elbe Germans , east of the Warnow the Odermündungsgermanen . Roman imports from this period are well documented archaeologically.

Claudius Ptolemy mentions the rivers Chalusus, Suevus and Viadua to the east of the point where “the coast curves to the east” (inner Bay of Lübeck ) - followed by the Vistula ( Vistula ). East of the Saxones , who lived “on the neck of the Cimbrian Peninsula”, the Farodini sat by the sea from Chalusus to Suevus, then the Sidiners as far as the Viadua . Further inland, from the Elbe to the Suevus, lived the Semnones , as a sub-tribe of the Suebi, from there to the Vistula the Burguntae (Burgundians). The Viruni ( warning ?) Are mentioned as a small people between the Saxones and Semnones.

From the 4th century AD, these tribal associations took part in the migration of peoples, probably due to the deterioration in the climate, and left the Baltic coast towards the south. The apparently hardly populated area was settled by immigrating Slavs from around the 7th century .

middle Ages

Slavic time

Initially, only archaeological finds and, at the end of the 8th century, written sources from neighboring cultures provide information about the immigrating Slavs. According to this, Slavs had resided in Mecklenburg since the middle of the 7th century, from which the tribal associations of the Abodrites in western Mecklenburg and Ostholstein and the Wilzen in eastern Mecklenburg and Western Pomerania were formed. In the 10th century, the Lutizen tribal union was formed in the Wilzen area .

The Abodrites initially consisted of a large number of small tribes whose leaders allied with Charlemagne against the Saxons at the end of the 8th century , but also maintained contacts in the Scandinavian region. From the 10th century onwards, larger sub-tribes became tangible with the Wagriern in Ostholstein , the Abodrites in the narrower sense between Wismar and Schwerin, and the Kessinern between Rostock and Güstrow . While the neighboring Slavic tribes were subjugated by the East Franconian-Saxon emperors, the Abodrites maintained their ethnic identity and political independence. With the Christian Naconids, they provided one of the most powerful Slavic royal houses of that time. The Naconids resided on the eponymous Mecklenburg in today's village of Mecklenburg , which was first mentioned in a document from Otto III. from the year 995 is mentioned. An impressive earth wall still bears witness to the castle, which was built between 780 and 840. The Nakonide Gottschalk established a "modern" territorial state based on the Scandinavian-Polish model in the 11th century, but died in 1066 in a revolt of the pagan nobility. After his son Heinrich was able to expand the Abodritic territory at the beginning of the 12th century to the Oder and Spree, the Abodritic Empire split into two with the murder of his successor Knud Lavard .

In the western part with Wagria and Polabia , the Slavic rule of Pribislaw dissolved after the winter campaign of the Saxon Count Heinrich von Badide in 1138/1139. In the east, Niklot recognized the sovereignty of Lothar of Supplinburg . After his death in 1137 he ruled like a king in the Abodritenland , but became a vassal of the Saxon Duke Henry the Lion in the course of the Slavic Crusade in 1147 . By complying with his vassal obligations, Niklot preserved the political independence of the Abodritic country. It was only Niklot's open rebellion against the ban on continuing the sea war against the Danes in 1160, leading to Henry the Lion's punitive expedition and to Niklot's death. To secure his rule in the Abodritenland, Heinrich set up Saxon bases in Mecklenburg, Ilow , Schwerin , Quetzin and Malchow and ordered the reconstruction of the Slavic castle Schwerin. The attempt to settle Flemish colonists around Mecklenburg ended in 1164 with the death of the settlers and the loss of the castle to Niklot's son Pribislaw . In 1167, after further heavy fighting, Heinrich the Lion and Pribislaw settled. The Abodriten prince recognized the sovereignty of the Saxon Duke and received in return the Terra Obodritorum as a fief . Only the newly established county of Schwerin in the extreme south-west remained in Saxon hands.

Medieval country development

From 1200, the Slavic princes brought several thousand German settlers from Westphalia , Lower Saxony , Friesland and Holstein into the country. Since the second half of the 12th century, German ministerials , servants in court and administrative service, received fiefdoms with the task of colonizing Mecklenburg and redesigning it according to their experience. The farmers received tax-free hooves as a fiefdom and settled from west to east, especially in the area of the heavy soils north of the north Brandenburg ridge in areas that were previously hardly or entirely uninhabited apart from island-like settlements . The settlers measured the arable land, hoofed it and cleared the thick beech forests of the heavy terminal moraine soils . Place names with the ending "-hagen" still indicate these settlements, as the clearings were called Hagen and often bore the name of a dominant person in the clearing community. Such naming can be found in particular in the greater Rostock area , such as the places Diedrichshagen or Lambrechtshagen .

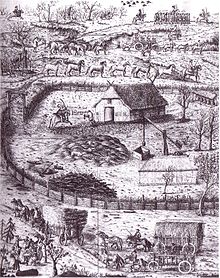

Agriculture among the Slavic tribes was less developed, was only practiced with wooden plows for centuries and had low yields, which did not lead to prosperity and tax or tribute potential for possible feudal lords. The iron plow became the most important tool of the new settlers . With the German settlers, the three-field economy with advanced agricultural technology was introduced. The villages were laid out on a large scale and according to plan. The Slavic parts of the population were included in the settlement. In the southwest of Mecklenburg and on Rügen , larger closed Slavic settlement areas were preserved for some time. Merchants and craftsmen poured into the country along with the farmers. Often the new settlements were also next to the old Slavic settlements. This is still indicated today by names such as large and small, German and Wendish or old and new.

After 1200 the settlement also took place in the wetlands, especially in the Mecklenburg Lake District , and in the hinterland. The villages were laid out on a large scale and according to plan: Anger villages with a wide space between rows of houses, mostly elongated or rectangular meadows and corridors . These settlements today point to place names ending in -busch, -dorf, -feld, -heide, -hof, -krug, -wald (e), -mühlen, -berg, -burg, -kirchen, -ade or -rode .

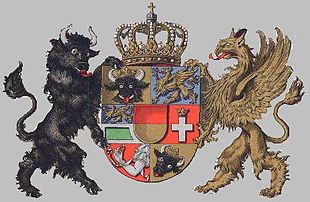

An important cultural asset that still exists today was the Low German language , which spread with the settlers in Mecklenburg, both in its Westphalian and in its northern Lower Saxon form. During this time (around 1219) the bull's head appeared for the first time as a Mecklenburg heraldic animal. Of the 56 cities in Mecklenburg, 45 were founded during the colonization period.

First division of Mecklenburg mainland (1234)

The phase of formation and development of Mecklenburg to a German territorial state took about two and a half centuries between the first Mecklenburg main state division and the time of Duke Heinrich IV. (The Fat).

After it was Pribislaw succeeded to the county Schwerin to unite all the Mecklenburg land among themselves, came in 1226 after the death of Henry Borwins II. For First Mecklenburg main division of the state . The dominions (principalities) of Mecklenburg, Werle , Parchim-Richenberg and Rostock emerged . The rule of Parchim-Richenberg only lasted until 1256. Pribislaw I. von Parchim-Richenberg came into contradiction with the Schwerin bishop Rudolf I. He had Pribislaw put under imperial ban and obtained a papal ban . Pribislaw was disempowered and the land was divided between his brothers and his brother-in-law, the Count of Schwerin . The rulership of Rostock was able to withstand the Mecklenburg power struggle with Danish help until 1312. After an unsuccessful attempt in 1299, Henry II , called the Lion , succeeded in taking the country in 1312. After the conclusion of peace in 1323 with the Danish king, he finally received the rule of Rostock from him as a fief.

On August 12, 1292, Heinrich II married Beatrix , the daughter of the Brandenburg margrave Albrecht III. who owned the Stargard reign . After his death there were inheritance disputes between Heinrich II. And the Margraves of Brandenburg. As a result, they left him - with the Wittmannsdorf Treaty of January 15, 1304 - the land as a fief. After Beatrix's death in Wismar in 1314, the ruling Brandenburg Margrave Waldemar regarded the Land of Stargard as a settled fiefdom and wanted it back. In 1315 during the North German Margrave War (1308-1317) he invaded Mecklenburg. However, Waldemar and his allies were defeated in the Battle of Gransee in August 1316 and driven out of the country. With the Templin Peace of November 25, 1317, Henry II was finally awarded the rule of Stargard as a Brandenburg fief.

During the Brandenburg Interregnum (1319–1323) Heinrich II of the Mark Brandenburg conquered the Prignitz and temporarily and partially the Uckermark . He had to give up these areas again in 1325. The War of Succession after the death of the last Rügan prince Wizlaw ended without any territorial gains. After Heinrich's death in 1329 and several years of guardianship and joint government (since 1336), his sons Albrecht II and Johann I divided their territory into the (partial) duchies of Stargard and Schwerin in 1352 .

The house of Mecklenburg was able to use the turmoil after the extinction of the Brandenburg Ascanians to consolidate its position and to achieve imperial immediacy. In 1347 Albrecht and Johann received the rule of Stargard and in 1348 also the rule of Mecklenburg from King Charles IV (the later Emperor) as an imperial fief and were now imperial princes with a simultaneous increase in rank to dukes.

In 1358 Albrecht II acquired the County of Schwerin and the Dukes of Mecklenburg relocated their residence from Mecklenburg near Wismar to the inland Schwerin Castle Island, on which the Schwerin Castle was later rebuilt .

The rule Werle lost more and more of its importance after several partitions. Only in 1425 was the rule reunited under a regent ( Wilhelm von Werle ). When he died in 1436 without a male heir, Werle fell to the Duchy of Mecklenburg. After the last regent of the partial duchy of Mecklenburg-Stargard Ulrich II died in 1471 without a male heir, all territories under Heinrich the Dicken were in the hands of a single regent and all parts of Mecklenburg's rulership, which, however, continued to function as administrative structures well into modern times lived on inside were united. The provincial estates, which had been separated up to that point, were then called to joint state parliaments. This was also retained after the later partitions.

Outwardly, there were changes to the national borders between 1276 and 1375. In 1276, Wesenberg came to the Mark Brandenburg , but around 1300 the rule of Stargard came into the hands of the Mecklenburgers. The town and state of Grabow fell to Mecklenburg in 1320 and Dömitz came to Mecklenburg in 1375 .

The state estates in Mecklenburg were formed in the 13th century, when initially the knighthood, the totality of vassals in Mecklenburg, were called together in certain matters (e.g. guardianship for minorenne monarchs). The landscape , the representation of the rural cities (cf. Landstadt in Mecklenburg ), goes back to the beginning of the 14th century, when the knighthood invited representatives of the cities to their meetings. Since the effective collection of taxes for state purposes, the revenue of which came primarily from the commercial turnover of city merchants and from the wages of free city dwellers, required the cooperation of the city tax authorities, the introduction or change of each individual tax was subject to the approval of the Mecklenburg state parliaments. The representatives sent there represented the landscape, knighthood and, since the beginning of the 15th century, also prelates , who all three together made up the estates. "Their further formation took place in the constant power struggle with the state rulers." Since the unification of Mecklenburg under Heinrich IV. The Fat in 1471, the respective estates of the three partial rulers Mecklenburg (Mecklenburg District), Wenden (Wendischer District) and Stargard (Stargard District) increasingly gathered to joint diets before they formed a union in 1523 to counteract the imminent renewed dynastic division of the country by Albrecht VII . From then on, the united states, also known as the state union, were the bond that held the Mecklenburg part-rulers together.

The prelates were representatives of the monasteries and collegiate monasteries in the country, which lost their importance in the course of the Reformation. In 1549, prelates were last called to a Landtag and were no longer recognized as eligible for a Landtag in 1552. Three monasteries (henceforth the so-called state monasteries Dobbertin , Machow and Ribnitz ) passed into the control of the knighthood and landscape as Lutheran monasteries in 1572 . Since the departure of the prelates, the knighthood and landscape formed the state estates of Mecklenburg. From 1763, the dukes in Schwerin recognized Mecklenburg-Schwerin's rural Jewry as a representative body without legislative powers but with internal autonomy, while the knighthood and landscape rejected their existence.

In the high Middle Ages, Mecklenburg was under the influence of the Hanseatic League . The Mecklenburg cities of Rostock and Wismar joined the powerful trade alliance. In addition, there was the involvement in Scandinavian politics, especially under Duke Albrecht II. His son, Albrecht III. , temporarily held the Swedish throne. In 1370 the Hanseatic League gained the upper hand after the Second Waldemark War and ended the Danish supremacy in the Baltic Sea region in the Peace of Stralsund . In 1419 the Dukes Johann IV and Albrecht V of Mecklenburg and the Council of the Hanseatic City of Rostock founded the University of Rostock as the first university in northern Germany and the entire Baltic region .

After the Peace of Wittstock on April 12, 1442, Mecklenburg finally lost control of the Uckermark to the Mark Brandenburg . In addition, the peace established the right of the Brandenburgers to contingent succession in Mecklenburg in the event of the Mecklenburg Princely House becoming extinct in the male line capable of following the throne.

Early modern age

At the end of the 15th century the outer borders of Mecklenburg were largely fixed, but the Mecklenburg sovereigns gained further territorial gains by the middle of the 17th century. New land divisions in 1520 ( Neubrandenburg house contract ), 1555 (Wismar joint agreement ) and since 1621 (Güstrow reversals and inheritance contract) again produced two (partial) duchies: Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Mecklenburg-Güstrow .

In 1523 the Mecklenburg territorial estates ( prelates , knights , cities) united to form a single body that lasted until the end of the monarchy. The estates had far-reaching privileges, such as the absolute right of tax approval, confirmed in the Sternberg Reversals in 1572 in return for assuming ducal debts. In the decades that followed, the estates were able to have more and more ducal assurances enshrined and thus expand their power at the expense of the ducal central authority. Although the estates prevented a fragmentation of Mecklenburg, they are also one of the reasons for the relative backwardness of the country in the following centuries.

reformation

From 1523 the Reformation , which was mainly driven by the reformers Joachim Slüter (Rostock) and Heinrich Never (Wismar), found its way into Mecklenburg. Here the Lutheran character was predominant. Rostock officially became Protestant as early as 1531 . As a staunch supporter of Protestantism , Johann Albrecht I, in contrast to his father Albrecht VII , resolutely advocated the introduction of the Reformation in his countries. He surrounded himself with men of Protestant sentiment and appointed Gerd Omeken to be Lutheran court preacher. He drew District Administrator Dietrich v. Maltzan, who had professed the Lutheran faith early on among the Mecklenburg nobility, to his court and also induced his uncle, Heinrich V , to campaign for the new faith. In June 1549, Johann Albrecht I enforced Lutheran doctrine for all states in the Sternberg state parliament. It was recognized as a national religion by all classes. This act can be seen as the legal introduction of the Reformation in Mecklenburg.

However, Johann Albrecht I could not turn against the Emperor Charles V alone , who wanted to prevent the recognition of Protestantism under imperial law and limit the power of the imperial estates in the Holy Roman Empire and was at the height of his power at this point. Therefore, Johann Albrecht I initially sought an alliance with the other princes of Northern Germany. As early as February 1550, he won over the Margrave Johann von Brandenburg-Küstrin to sign a defensive alliance with Duke Albrecht of Prussia , to whose daughter Anna Sophie he became engaged and whom he later married.

On May 22, 1551, he secretly formed an alliance with the other Protestant princes of Northern Germany in the Treaty of Torgau . The Treaty of Torgau formed the legal framework for the prince uprising against Emperor Charles V, in which Johann Albrecht I also participated. The Augsburg Religious Peace of 1555 secured the Protestants the desired freedom of religion and the independence of the German imperial princes. After his return from the campaign, Johann Albrecht I saw the complete implementation of the Reformation as his main task. In 1552 he dissolved almost all Mecklenburg monasteries and incorporated them into the ducal domains . The church then lost its influence. In addition, he carried out church visits , established Protestant scholarly and elementary schools and appointed Protestant theologians to the University of Rostock .

Second main division of Mecklenburg (1621)

After all parts of Mecklenburg had been reunited since 1471, the country was again divided in 1621. In the course of the second division of Mecklenburg , the (partial) duchies of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Mecklenburg-Güstrow came into being after the Fahrholz partition treaty. This subdivision already existed with a few interruptions after the death of Heinrich des Dicken in 1477 and again from 1520 (according to the Neubrandenburg house contract ), but only in the form of an allocation of offices for sole usufruct, while the state affairs remained common.

Thirty Years' War

Reasons for the involvement of Mecklenburg

The Mecklenburg dukes first tried to stay out of the beginning Thirty Years' War and to keep the peace in Mecklenburg through strict neutrality. When the imperial armies approached and the restoration of Catholicism and imperial absolutism threatened, the two dukes Adolf Friedrich von Schwerin and Johann Albrecht von Güstrow joined forces in 1625 despite imperial warnings with Braunschweig , Pomerania , Brandenburg , the free cities and Holstein under the leadership of the King Christian of Denmark formed a defensive alliance. However, the King of Denmark sought alliances with France , England and Holland against the German Emperor Ferdinand II at the same time and therefore gave the alliance a character hostile to the Emperor. Although both dukes had renounced the Danish king immediately after the battle of Lutter in 1626, they were ostracized and deposed by Emperor Ferdinand II between 1628 and 1630 and replaced as duke by his general Wallenstein . The emperor referred the complaining dukes to legal recourse.

Mecklenburg under the rule of Wallenstein

Wallenstein chose Güstrow Castle as his residence. From there he reformed the state system of the country during his short term in office (1628 to 1630). Although he left the old state constitution and its representation in place, he shaped the rest of the state system far-reaching. For the first time in the history of Mecklenburg, he separated the judiciary and administration (so-called "chamber"). He established a " cabinet government ", which he himself headed. This consisted of a cabinet for war, imperial and domestic affairs and a government chancellery for the overall direction of the government. He issued a poor welfare order and introduced the same weights and measures.

Recapture with the help of Sweden

While in exile, the Mecklenburg dukes tried to regain their lands and got in touch with their cousin, the Swedish King Gustav Adolf . He declared war on the German Emperor in 1629 and came with his war-tested army in September 1630 via Pomerania to Mecklenburg, where he conquered the cities of Marlow and Ribnitz , which were occupied by imperial troops . In February 1631 he occupied Neubrandenburg with 2,000 men and had it heavily fortified. But only a month later the imperial general Tilly besieged and stormed the city with great losses and caused a terrible bloodbath among the Swedes and the inhabitants. The city was badly destroyed.

As early as 1630, the Mecklenburg dukes were reinstated by the Swedish King Gustav Adolf and all of Wallenstein's reforms were repealed. In July 1630 the Mecklenburg dukes set out from Lübeck for Neubrandenburg using Swedish funds and troops with about 2000 men . When the city was about to be stormed, the imperial garrison surrendered against free withdrawal. The combined Mecklenburg and Swedish armies continued to take the other permanent places - cities, castles and fortresses - together. Plau Castle was handed over to the Swedish troops as early as the end of June after its imperial commander had set fire to the town for defense and half burned it down. At the end of July the army stood before Wismar , which, along with the island of Walfisch , was stubbornly held by the imperial troops. Only in January 1632, due to a lack of provisions and outside help, was the handover against withdrawal with all warlike honors. In 1631 Warnemünde was conquered by the Mecklenburgers and in October the imperial troops in Rostock surrendered after a siege lasting several weeks .

At the end of January 1632, the last imperial troops had withdrawn from Mecklenburg, and the Swedes also withdrew except for the garrisons in Wismar and Warnemünde. On February 29, 1632, the Mecklenburg dukes in Frankfurt am Main signed a firm alliance with Gustav Adolph, in which the Swedish occupation of Wismar and Warnemünde was expressly reserved. Wismar was lost to Mecklenburg before the Peace of Westphalia and became an entry and exit gate for the Swedish armed forces and the center of attraction for Sweden's enemies.

Reconciliation with the emperor and cession of territory to Sweden

With the Peace of Prague , which the Mecklenburg dukes also subsequently joined, the dukes were reconciled with the emperor in 1635, who then recognized them again as dukes. However, Mecklenburg did not take part in the war against Sweden. Nevertheless Sweden threatened Mecklenburg with war, occupied and pillaged Schwerin and took the fortresses Dömitz and Plau without a fight . The Swedish garrison at Wismar made itself felt in the surrounding area through looting and acts of violence. At Bützow and Güstrow several companies of Mecklenburg troops were easily placed under Swedish regiments.

Between 1637 and 1640 there was again frequent fighting between Swedish and imperial troops on Mecklenburg soil. In the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the Mecklenburg city of Wismar (with the Neukloster office and the island of Poel ) had to be ceded to Sweden as an imperial fiefdom, whereas the Schwerin line with the secularized dioceses of Schwerin and Ratzeburg and the Johanniterkomturei Mirow and the Güstrowsche line with the Commandery Nemerow compensated were. Wismar became the seat of the Upper Tribunal Wismar , the highest court for the Swedish territories in the empire . It was not until 1803 that Wismar, including Neukloster and the island of Poel, came back to Mecklenburg.

Effects of the war

The effects of the war in Mecklenburg were devastating. The population was reduced to one sixth (from 300,000 to approx. 50,000). Large parts of the country were devastated and atrocities were perpetrated against the population. The peasant class in particular had suffered greatly and lost most of its freedom. Towns, towns and farms had been burned to the ground or demolished for use as firewood and for building camps. The rough Swedish Field Marshal Johan Banér , used to horrors of war, described the situation in Mecklenburg in a letter from September 1638 to the Swedish Chancellor Oxenstjern as follows:

- "In Meklenburg there is nothing but sand and air, everything devastated down to the ground" -

and after the plague also broke out, which wiped out thousands in the medium-sized country towns and hundreds in the smaller ones:

- "Villages and fields are sown with creeping cattle, the houses full of dead people, the misery cannot be described."

The inhabitants of Mecklenburg had perished from sword and torture, from plague and starvation. Parts of the population were able to flee to the fortified cities of Rostock , Lübeck and Hamburg . The cities with permanent castles - Dömitz , Plau , Boizenburg - were almost completely reduced to rubble during the sieges, as were the cities of Warin , Laage , Teterow and Röbel . The Crabats (Croats) under their supreme commander Colonel Lossi and the imperial troops under Colonel Graf Götzen acted particularly brutally against the civilian population. In a daily order from 1638, in which he ordered his officers to refrain from any excesses against the population, the Swedish Field Marshal Johan Banér describes the atrocities of the Soldateska against the rural population. He reports from

- “... cruel excesses, robbery, murder, looting, burning, desecration of women and virgins, regardless of class and age, devastation of churches and God's houses, and insulting preachers and church servants, desolation of God's gifts and other barbaric ones Crudeliteten ... "

After the war, the dukes tried to rebuild the country's economy, which consisted mainly of agriculture. However, only about a quarter of the abandoned and devastated farm positions could be reoccupied and cultivated. In 1662, by order of the duke, 10 farmers were to be settled in each office and the buildings were to be erected, the fields sown and also given several years off at the lordly expense. In addition, inquiries were made for any existing children of the earlier farming families in order to bring them back to their hooves , if not amicably, at least in accordance with the right of serfdom . Numerous immigrants came from the Mark Brandenburg , Holstein and Pomerania who had lost their property there. Nevertheless, the number of former farmers could not be reached by far. The landlords could easily assert themselves against the severely decimated peasant class and worsen the peasant law. The extensive depopulation of the country led to large-scale farming - abandoned farms were confiscated by the knightly lordship and incorporated into their own property, the farmers on the occupied farm positions became dependent. In 1646 the Mecklenburg community order was enacted and expanded in 1654, it said:

- “Of peasant people and their easement and delivery.

- §1 We arrange and set after daily experience testifies that the peasants and subjects, men and women, undertook this time in many ways to join together, to betroth and free themselves, without their masters and authorities knowing and consenting, but this because according to their rulership of these Our lands and principalities, they use servants and servants with their wives and children and are therefore not capable of their own person, nor to withdraw and betroth themselves to them without their masters' approval, to some degree. That we therefore want to have completely forbidden and abolished such presumptuous, secret engagements and freedoms of the peasant people. "

The peasant class had thus largely lost its freedom and serfdom was enshrined in law . Accordingly, the farmers were no longer allowed to leave their jobs without the landlord's permission. A marriage was also only possible with the permission of the landlord.

Witch madness in Mecklenburg

In Mecklenburg the witch hunt was carried out particularly intensively. About 4000 trials of alleged witches were carried out and about 2000 death sentences passed. In the 16th century, the number of witch trials rose sharply, only to peak in the 17th century, especially before and after the Thirty Years' War. The last known witch trial in Mecklenburg was carried out in 1777.

Nordic Wars

From the second half of the 17th century, the Northern Wars were partly fought on Mecklenburg soil. In the Second Swedish-Polish War , imperial, Brandenburg and Polish soldiers marched into Mecklenburg in 1658, and until the end of the war with the Treaty of Oliva in May 1660, warlike burdens such as at the time of the Thirty Years' War occurred again.

The Güstrow line expired in 1695 with Johann Albrechts II (d. 1636) son Gustav Adolf . In the line of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Adolf Friedrich I ruled , who was constantly in conflict with the estates and all members of his family, until 1658. His son and successor Christian Ludwig lived mostly in Paris , where he converted to the Catholic denomination in 1663 and Louis XIV . related.

In the Swedish-Brandenburg War (1674–1679) , Mecklenburg was therefore occupied by Brandenburg and Danish troops despite its neutrality. In 1675 the Danes conquered Wismar, but it became Swedish again in 1680 and was expanded into a fortress. In the Great Northern War (1700–1721) there was looting by the warring parties: Sweden against Prussia, Danes, Saxons and Russians.

Third main division of Mecklenburg (1701)

In 1701 the Mecklenburg Princely House was able to agree on the principle of succession of primogeniture . Before that, after the Mecklenburg-Güstrow line had died out, Mecklenburg was once again embroiled in long-standing inheritance disputes, which were settled with the significant participation of foreign powers by the Hamburg settlement of March 8, 1701, concluded as a house contract . The agreed third division of Mecklenburg mainland again formed two limited autonomous (partial) duchies, from 1815 (partial) grand duchies: Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Mecklenburg-Strelitz . As an outward sign, the two reigning dukes (later grand dukes) of both parts of the country had absolutely identical titles, their enfeoffment was always made to the "entire hand" and their coats of arms differed only slightly. Both parts of the country were entitled to vote in the Federal Council , Schwerin with two votes, Strelitz with one vote.

Execution of the Reich and controversy for succession to the throne

In 1713 there was a conflict between Duke Karl Leopold , the regent of the Mecklenburg-Schwerin region, and the Mecklenburg Land estates, which lasted until 1717. The duke tried to enforce sovereign, absolutist sovereignty against the knighthood and against Rostock, allied with them. He called on the estates to grant him additional taxes in order to build up a standing army, then forced the Rostock council to renounce its privileges.

After complaints from the Mecklenburg estates before the head of the empire against Karl Leopold's breaches of law and autocratic efforts, Emperor Karl VI. 1717 the execution of the Reich against the Duke was imposed. The execution of the Reich execution took place in the spring of 1719. Karl Leopold initially holed up in the fortress Dömitz and soon afterwards left the country. The government in Mecklenburg-Schwerin was taken over by the Elector of Hanover and the King of Prussia. After the death of Elector Georg Ludwig von Hannover (1727), the execution of the Reich was overturned. Since the conflict initially failed to settle, Karl Leopold was finally deposed in 1728 by the Reichshofrat in Vienna in favor of his brother Christian Ludwig II .

Karl Leopold rejected every compromise proposal from Charles VI. and failed in 1733 in an attempt to regain power in Mecklenburg-Schwerin with the help of a contingent of citizens and farmers, but also with Prussian support. In 1734, Hanover occupied eight Mecklenburg offices on the pretext of covering the costs of its execution. Karl Leopold finally died on November 28, 1747 in Dömitz.

In a final surge of absolutist thirst for power in 1748, the two Mecklenburg regents, Christian Ludwig II and Adolf Friedrich III. in a secret treaty the dissolution of the Mecklenburg state as a whole. However, this project also failed due to the bitter resistance of the knighthood. When the succession to the throne suddenly occurred in 1752 in Strelitz, the situation escalated. Troops of the Schwerin Duke occupied the Strelitz part of the country in order to enforce its political independence after decoupling from the state of Mecklenburg. The outcome of the succession dispute ended this last rebellion of the prince's power in Mecklenburg and brought about the further strengthening of the estates.

Prussian annexation plans

Prussian policy towards Mecklenburg went beyond participation in the execution of the Reich and meddling in disputes about the succession to the throne. Even as Crown Prince, the later Prussian King Friedrich II had described the rounding off of Prussia by Mecklenburg as a "political necessity". In a letter to Dubislav Gneomar von Natzmer in 1731, he expressed the hope that one would “only need to wait for the ducal house to go out” and then “pocket the land without further formalities”. In his (first) Political Testament , as King in 1752, he affirmed these claims to Mecklenburg based on the Peace of Wittstock in 1442 and gave his successors instructions on what to do if he himself would no longer experience this succession.

“ Our claims to Mecklenburg are clear [...]; they are based on a hereditary brotherhood concluded between the Electors [of Brandenburg] and the Dukes of Mecklenburg; […] There are currently eight Mecklenburg princes [dukes]; the succession does not seem to be given anytime soon […] If it should arise later, I would think that one should take possession of the duchy without delay […] and defend one's rights with sword in hand; for the right of possession in the Holy Roman Empire offers a great advantage if one can get income from an acquisition in peace and quiet. "

In fact, in the Seven Years' War , after the dukes of Mecklenburg had agreed on an internal inheritance settlement in 1755 and Friedrich von Mecklenburg-Schwerin had sided with Austria, left the duchy of Austria occupied in 1757. Forced recruitment and heavy levies filled the Prussian regiments. In addition, the occupied duchy had to provide contribution money. Although the Prussian occupiers left Mecklenburg in 1762 after a peace treaty and the payment of further contributions, Frederick II adhered to the rounding claims in his (second) Political Testament of 1768.

Land constitutional comparison of inheritance

As a kind of declaration of surrender by the monarchs, Christian Ludwig II signed the Land Constitutional Hereditary Comparison (LGGEV) in 1755 . The Strelitz Duke Adolf Friedrich IV. And his mother, in their capacity as guardian of his younger siblings, ratified the large agreement in the same year.

With the state constitutional comparison of inheritance, the Mecklenburg state had received a new, rural constitution. This led to the consolidation of the political supremacy of the Mecklenburg knighthood and preserved the backwardness of the country until the end of the monarchy (1918). Both parts of the country remained part of a common state, had a common constitution in the LGGEV and were subordinate to a joint state parliament, which met annually as legislature in Sternberg or Malchin and as executive in Rostock maintained the select committee . Each of the two parts of the country, whose regents had guaranteed non-interference in the affairs of the other part of the country in house contracts, had their own government agencies and had their own publication organs for laws and ordinances. The higher appeal court (in Parchim, later in Rostock) and the state monasteries remained together. There were no border controls between the two parts of the country. Customs duties were also not levied between the parts of the country. The state constitution in Mecklenburg was in force until 1918 and gave the large landowners decisive power. At the end of the monarchy, the political system in Mecklenburg was considered the most backward in the entire German Empire.

Independence from the Imperial Jurisdiction

The Mecklenburg diplomat Ernst Friedrich Bouchholtz represented Mecklenburg at the Peace of Teschen (1779) and achieved the Privilegium de non appellando for the Dukes of Mecklenburg at this peace treaty .

Buyback of Wismar

At the end of the 18th century, it became clear to Sweden that the bridgehead function of the Wismar rule as a link between the territories of Bremen-Verden and Swedish-Western Pomerania was no longer given with the loss of Swedish ownership between the Elbe and Weser in 1715. With the Malmö pledge agreement of 1803 , Wismar, the island of Poel and the Neukloster office became Mecklenburg again, initially for 99 years, and finally with a further waiver in 1903. In this context, the Wismar Tribunal was moved to Stralsund in 1802 and then to Greifswald in 1803 .

Mecklenburg as an exchange object

After the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation , both parts of Mecklenburg joined the Rhine Confederation in 1808 . Nevertheless, on the eve of the Russian campaign , Napoleon offered the Swedish ruler Bernadotte in 1812 Mecklenburg, Stettin and the entire area between Stettin and Wolgast.

In return, Mecklenburg-Schwerin also developed ambitions for territorial expansion during this period. He was particularly interested in Swedish Pomerania, whose property they wanted to secure after joining the Rhine Confederation. The Hereditary Prince Friedrich Ludwig therefore traveled both to Paris and to the Prince's Day in Erfurt, which was convened by Napoleon. The diplomatic efforts to acquire Swedish Pomerania lasted until 1813, according to the reports of the Oberhofmeister von Lützow, who was sent to Paris.

After Napoleon's defeat in Russia, the Mecklenburg duchies joined the Russians at the same time as Prussia, but in 1813 Prussia and Russia again negotiated them as a barter. For a change of sides by the Napoleonic ally Denmark and its renunciation of Norway in favor of Sweden, Denmark was offered not only Swedish Pomerania , but also rule over both Mecklenburgs, later even Prussian Western Pomerania (acquired by Sweden in 1720) as well as Lübeck and Hamburg. Denmark, however, remained loyal to Napoleon and after his defeat in 1814 only received Swedish Pomerania as compensation for Norway, the dukes of Mecklenburg could thus remain on their thrones for another century.

From the Congress of Vienna to the end of the monarchy

At the Congress of Vienna in 1815, both parts of the country were raised to grand duchies - Mecklenburg-Schwerin on June 14, 1815, Mecklenburg-Strelitz after Prussia's influence on June 28, 1815. The state independence of Mecklenburg was preserved, the rulers of both parts of the country were now titled as identical Grand Duke of Mecklenburg and had acquired the right to address Royal Highness .

In 1820 serfdom was lifted in Mecklenburg . The rural population in particular gained personal freedom as a result. At the same time, the landowners no longer had traditional custody obligations (job security, social, health and retirement benefits) for their subjects. Many landowners then went over to a capitalist, profit-oriented economy. Countless farm workers lost their jobs, mostly also their homes, i.e. all means of livelihood in their previous hometown. Although they formally retained their right of birth acquired by birth in Mecklenburg, they were no longer able to find admission or new homes in any other place in the state, since Mecklenburg did not have the right to settle freely and the local authorities granted arbitrary relocation permits. Because of the imperfection of the laws, the peasants could not achieve real independence. Many of them were subsequently forced to emigrate.

In the course of the revolution of 1848/49, countless reform associations were formed. On the basis of general, equal but indirect elections, the first democratically elected assembly of representatives was established in the autumn of 1848. The political goal was the elimination of the survived land-class system in Mecklenburg and the introduction of a constitutional monarchy. This was only possible by abolishing the traditional division of the country into two parts of the country. In this existential situation, Mecklenburg-Strelitz left the path of democratic renewal very quickly. On October 10, 1849, a new constitutional constitution came into force for Mecklenburg-Schwerin alone , which is considered to be one of the last state constitutions of the bourgeois-democratic revolution in Germany. At the instigation of the knighthood and the arch-reactionary Strelitz Grand Duke Georg , a court decision issued as the Freienwalder arbitration on September 14, 1850 stopped all democratic developments in the state and led Mecklenburg back to the legal status before the revolution, the long-outlived state constitutional comparison of inheritance . Many of the leading Democrats were then persecuted, some sentenced to several years in prison and imprisoned. Most of them then left the country.

In the German War , both Mecklenburg Grand Duchies were allies of Prussia, but did not provide any troops worth mentioning; Strelitz delayed his mobilization until it was too late. The fact that both parts of the country - unlike many territories of the war opponents - were not annexed by Prussia in 1866, contrary to the long-cherished annexation plans since Frederick the Great, they owed the close relationship of their Grand Dukes to the Prussian King Wilhelm I : Friedrich Franz II. (Mecklenburg) was a son of Wilhelm's sister Alexandrine of Prussia (1803-1892) , who at that time still lived in the Schwerin Alexandrinen-Palais , the Strelitzer Friedrich Wilhelm II. (Mecklenburg) a direct cousin.

The constitutional question kept coming up in the years that followed. Regardless of all external developments in the empire, there were no decisive changes in the Mecklenburg constitutional system until 1918. Reich Chancellor Otto von Bismarck is credited with the remark that when the world ends, he will go to Mecklenburg, since everything will happen there 50 years later. The background to this remark was the fact that Mecklenburg remained the only territory in the German Empire without a modern constitution.

The medieval structure of the country was also evident in the land ownership: About half of the territory belonged to the Mecklenburg Princely House ( Domanium ). Most of the rest was owned by aristocratic, later increasingly also by middle-class landowners (knighthood). Both parts of the country were divided into domanial and knightly offices, the Mecklenburg state also into three knightly circles (Mecklenburg, Wenden and Stargard), of which Mecklenburg and Wenden in Rostock and Stargard in Neubrandenburg had their own state authorities.

Around 1900 more than 50% of the population was still working in agriculture. Approaches of industrialization there was in 1890 with the Neptun Shipyard in shipbuilding.

After the suicide of Adolf Friedrich VI. , the last Grand Duke from the House of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the Schwerin Grand Duke Friedrich Franz IV took over the task of administrator of the Strelitz part of the country shortly before the end of the monarchy . The negotiations now beginning about a succession to the throne in Mecklenburg-Strelitz and about its further fate were soon overtaken by the events of the November Revolution. Until the end of the monarchy in Mecklenburg and the abdication of Friedrich Franz IV. As Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and administrator of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the question of the Strelitz succession to the throne could not be resolved.

Mecklenburg in the Weimar Republic and in the time of National Socialism

It was only after the overthrow of the monarchy in 1918 that both parts of the country briefly achieved political independence as free states from 1918/19 . They maintained separate state parliaments, gave their own constitutions, but adhered to the common higher court of appeal. Mecklenburg-Strelitz, a state the size of a Prussian district, proved to be non-viable after just a few years and, from the end of the 1920s, conducted follow-up negotiations with Prussia, which were not concluded. Under National Socialist pressure, the state parliaments of both Free States under Reich Governor Friedrich Hildebrandt decided to reunite the state of Mecklenburg with effect from January 1, 1934.

1937 lost Mecklenburg by the Greater Hamburg Act , the enclaves of Mecklenburg-Strelitz in Schleswig-Holstein as the Domhof Ratzeburg and the communities Hammer, Mannhagen, Panten , Horst, forest field, in the Duchy of Lauenburg were integrated. In return, Mecklenburg received the communities of Utecht and Schattin (now part of Lüdersdorf ), which had previously belonged to Lübeck . It also received the previously Pomeranian exclave around Zettemin near Stavenhagen .

Mecklenburg in the GDR and in the Federal Republic

The state of Mecklenburg was on June 9, 1945 order of the Soviet Military Administration in Germany with the remaining in Germany part of the Prussian province of Pomerania ( Vorpommern ) and formerly the Prussian province Hannover belonging Amt Neuhaus on the Elbe to the new land Mecklenburg-Vorpommern combined. The official name of the country was changed to "Mecklenburg" on Soviet orders in 1947.

A further area adjustment took place in 1945 by changing the zone boundary between the British zone of occupation and the Soviet zone of occupation in the so-called Barber-Lyashchenko Agreement of November 13, 1945. The neighboring communities of Ratzeburg, Ziethen , Mechow , Bäk and Römnitz became the Duchy on November 26, 1945 Lauenburg struck. Until then they belonged to the Mecklenburg district of Schönberg (part of Mecklenburg-Strelitz until 1934 ) and came to the British Zone in exchange for the Lauenburg communities of Dechow , Thurow (now part of the community of Roggendorf ) and Lassahn . This change of area was retained even after German reunification in 1990.

In 1952, the state of Mecklenburg, like all other states of the German Democratic Republic, was dissolved and divided into districts : the Rostock district was formed from the coastal region , the west of Mecklenburg became the Schwerin district , and the east became the Neubrandenburg district . The latter districts also included territories of the previous state of Brandenburg. The Fürstenberger Werder with the city of Fürstenberg / Havel , reclassified from Mecklenburg to the State of Brandenburg (1946–1952) as early as 1950 , now came to the Potsdam district .

In 1990, towards the end of the GDR, newly founded, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania has been part of the Federal Republic of Germany since October 3, 1990 . The borders of 1952 were approximately restored, but essentially followed the district borders that emerged during the GDR era. The Neuhaus office moved to the state of Lower Saxony in 1993 for historical reasons , as did the Prenzlau, Templin and Perleberg districts of Brandenburg. As the capital, Schwerin prevailed against Rostock after a heated debate . A split of Vorpommern in the direction of Brandenburg as an alternative to the art state Mecklenburg-Vorpommern did not go beyond the presentation of some related initiatives.

Regents and chief officials

Dominions and (grand) duchies (1131-1918)

- 1st regent

- 2. Presidents of the Privy Council, Presidents of the Ministry

- → See the individual parts of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Mecklenburg-Strelitz .

State of Mecklenburg in the Third Reich (1934–1945)

On January 1, 1934, the Free States of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Mecklenburg-Strelitz were united under National Socialist pressure to form Mecklenburg. Friedrich Hildebrandt , NSDAP, was Reichsstatthalter and Gauleiter from 1934 to 1945 .

State of Mecklenburg in the Soviet zone of occupation (1945–1952)

From July 25, 1952 to October 3, 1990, the state of Mecklenburg was dissolved by the administrative reform of 1952 and divided into the Rostock district , the Schwerin district and the Neubrandenburg district.

See also

- Mecklenburg-Schwerin

- Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Mecklenburg coin history

- Administrative history of Mecklenburg

- List of monasteries, monasteries and commanderies in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania

literature

With the aim of completeness, all literature on Mecklenburg is listed in the state bibliography MV .

Important basic works on regional studies:

- David Franck : Old and New Mecklenburg: in it the history, services of God, laws and constitution of the Wariner, Winuler, Wenden, and Saxony, also of this country princes, bishops, nobility, cities, monasteries, scholars, Müntzen and antiquities credible historians, archival documents and many diplomats have been described in chronological order [...]. 20 volumes, Güstrow / Leipzig 1753–1758. (Individual volumes listed under: David Franck → Literature )

- Yearbook of the Association for Mecklenburg History and Archeology. Schwerin, since 1834 [ongoing, 1 year volume]

- Ernst Boll : History of Meklenburg. With special consideration of the cultural history. Reprint of the 1855 edition. [With additional supplements]. Federchen Verlag, Neubrandenburg 1995. ISBN 3-910170-18-8 .

- Karl Hegel : History of the Mecklenburg Land estates up to 1555. Adler, Rostock 1856. [Reprinted several times.]

- Otto Vitense : History of Mecklenburg. Perthes, Gotha 1920. [Reprinted several times. ISBN 3-8035-1344-8 ].

- Ground plan for the German administrative history 1815–1945 . Row B, Vol. 13: Mecklenburg. Arranged by Helge bei der Wieden. Marburg, 1976, ISBN 3-87969-128-2 .

- Hermann Heckmann (Ed.): Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. Historical regional studies of Central Germany. Central German Cultural Council Foundation, Bonn 1989, ISBN 3-8035-1314-6 .

- Wolf Karge, Hartmut Schmied, Ernst Münch: The history of Mecklenburg. Hinstorff, Rostock 1993. [Reprinted several times; 4th, exp. Edition: 2004, ISBN 978-3-356-01039-8 ].

- Biographical lexicon for Mecklenburg. Rostock; Lübeck since 1995 [ongoing]

- A millennium of Mecklenburg and Western Pomerania. Biography of a north German region in individual representations. Rostock 1995, ISBN 3-356-00623-1 .

- Gerhard Heitz , Henning Rischer: History in data. Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. Koehler & Amelang, Munich and Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-7338-0195-4 .

- Landeskundlich-historical Lexikon Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Published by the Geschichtswerkstatt Rostock eV Hinstorff, Rostock 2007, ISBN 3-356-01092-1 .

- Wolf Karge, Reno Stutz: Illustrated history of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. Rostock 2008. ISBN 978-3-356-01284-2 .

- Grete Grewolls: Who was who in Mecklenburg and Western Pomerania. The dictionary of persons . Hinstorff Verlag, Rostock 2011, ISBN 978-3-356-01301-6 .

- Michael Buddrus , Sigrid Fritzlar: State governments and ministers in Mecklenburg. A biographical lexicon. Edition Temmen, Bremen 2012, ISBN 978-3-8378-4044-5 .

- Michael Buddrus, Sigrid Fritzlar: Jews in Mecklenburg 1845-1945. Paths and fates. With the special collaboration of Ute Eichhorn, Angrit Lorenzen-Schmidt, Martin Wische. Ed .: Institute for Contemporary History Munich - Berlin, State Center for Political Education Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. Two volumes. Schwerin 2019.

Web links

- State Bibliography Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania

- Policey and Landtordenunge Johann Albrechts I Rostock 1562. ( digitized )

- Reformation and Court of Justice order our by the grace of God Johans Albrechte and Ulrichen brothers from Hertzog zu Meckelnburg. Rostock 1568. ( digitized version )

- Policey and Landtordenunge Johann Albrechts I Rostock, 1572. ( digitized )

- Carl von Lehsten: About the abolition of serfdom in Mecklenburg. Parchim 1834. ( digitized version )

- Carl Friederich Wilhelm Bollbrügge: The rural people in the Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. Statistical-cameralistic treatise on the condition and conditions of the rural population of the peasant class in Mecklenburg and on the means to secure and increase their prosperity. Güstrow 1835. ( digitized version )

- Carl von Lützow: Mecklenburg-Schwerin in 1849. Schwerin 1850. ( digitized version )

- Georg Christian Friedrich Lisch : Wallenstein's poor welfare order for Mecklenburg . 1870. ( full text )

- Traugott Mueller: Handbook of real estate in the German Empire. The Grand Duchies of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Strelitz. Berlin 1888. ( digitized version )

- Otto Grotefend: Meklenburg under Wallenstein and the reconquest of the country by the dukes. 1901. ( full text )

- Karl Wilhelm August Balck: Mecklenburg in the Thirty Years War. In: Yearbooks of the Association for Mecklenburg History and Archeology. Vol. 68 (1903), pp. 85-106. ( Full text )

- Otto Vitense : Mecklenburg and the Mecklenburgers in the great period of the German Wars of Liberation, 1813-1815. Neubrandenburg 1913. ( digitized version )

- Virtual state museum on the history of Mecklenburg

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ernst Eichler ; Werner Mühlner; Hans Walther [Hrsg.]: The names of the cities in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. Origin and meaning. Verlag Koch, 2002. ISBN 3-935319-23-1 : S 12.

- ^ Horst Keiling : Stone Age hunters and gatherers in Mecklenburg. Ed .: Museum for Pre- and Early History, Schwerin 1985. ISSN 0323-6765 .

- ↑ Horst Keiling: The cultures of the Mecklenburg Bronze Age. Ed .: Museum for Prehistory and Early History, Schwerin 1987. ISSN 0323-6765 .

- ↑ Ralf Loock: A river poses a riddle. In: Märkische Oderzeitung , April 10, 2010 ( full text , accessed June 27, 2013).

- ^ Claudius Ptolemaius: Geographia. (ancient Greek / Latin / English) digitized .

- ↑ Overview with Sebastian Brather: Archeology of the Western Slavs. Settlement, economy and society in early and high medieval East-Central Europe. ( Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde , Vol. 61). 2nd Edition. Berlin-New York 2008. Brather also points out on page 55 that there was no immigration of entire tribes or even tribal associations.

- ↑ The first mention of Slavs in the northwest is found in the Frankish imperial annals for the year 780: omnia disponens tam Saxoniam quam et Sclavos .

- ^ On the revised state of research by Torsten Kempke: Scandinavian-Slavic contacts on the southern Baltic coast in the 7th to 9th centuries. In: Ole Harck, Christian Lübke: Between Reric and Bornhöved. Relations between the Danes and their Slavic neighbors from the 9th to the 13th centuries. Contributions to an international conference, Leipzig, 4. – 6. December 1997. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2001. pp. 9-22 [here p. 10].

- ↑ First mentioned as Abodriti and Wilze in the Franconian Reichsannals for the year 789

- ↑ On these fundamentally Wolfgang Brüske, investigations on the history of the Lutizenbund. German-Wendish relations of the 10th - 12th centuries. 2nd Edition. Böhlau, Cologne a. Vienna 1983.

- ↑ Wolfgang H. Fritze: Problems of the abodritic tribal and imperial constitution and its development from a tribal state to a ruling state. In: Herbert Ludat [Hrsg.]: Settlement and constitution of the Slavs between the Elbe, Saale and Oder. W. Schmitz, Giessen 1960. pp. 141-219 [here p. 201].

- ↑ Fred Ruchhöft: From the Slavic tribal area to the German bailiwick. The development of the territories in Ostholstein, Lauenburg, Mecklenburg and Western Pomerania in the Middle Ages. (Archeology and History in the Baltic Sea Region, Volume 4). Rahden / Westf. 2008. ISBN 978-3-89646-464-4 . P. 89.

- ↑ Mecklenburgisches Urkundenbuch , Volume I, Certificate No. 22.

- ↑ Torsten Kempke: Scandinavian-Slavic contacts on the southern Baltic coast in the 7th to 9th centuries. In: Ole Harck, Christian Lübke: Between Reric and Bornhöved. Relations between the Danes and their Slavic neighbors from the 9th to the 13th centuries. Contributions to an international conference, Leipzig, 4. – 6. December 1997. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2001. pp. 9-22 [here p. 12].

- ↑ Fred Ruchhöft: From the Slavic tribal area to the German bailiwick. The development of the territories in Ostholstein, Lauenburg, Mecklenburg and Western Pomerania in the Middle Ages. (Archeology and History in the Baltic Sea Region, Volume 4). Rahden / Westf. 2008. ISBN 978-3-89646-464-4 . P. 86.

- ↑ Hans-Otto Gaethke: Duke Heinrich the Lion and the Slavs northeast of the lower Elbe. Lang, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1999. ISBN 3-631-34652-2 . P. 106 and 457. - Elżbieta Foster, Cornelia Willich: Place names and settlement development. Northern Mecklenburg in the Early and High Middle Ages. (= Research on the history and culture of Eastern Central Europe, Vol. 31). Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2007. ISBN 978-3-515-08938-8 . P. 26.

- ↑ Elżbieta Foster, Cornelia Willich: Place names and settlement development. Northern Mecklenburg in the Early and High Middle Ages. (= Research on the history and culture of Eastern Central Europe, Vol. 31). Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2007. ISBN 978-3-515-08938-8 . P. 26.

- ↑ Elżbieta Foster, Cornelia Willich: Place names and settlement development. Northern Mecklenburg in the Early and High Middle Ages. (= Research on the history and culture of Eastern Central Europe, Vol. 31) Steiner, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-515-08938-8 , p. 38.

- ^ Franz Boll : Heinrich von Mecklenburg in possession of the Land Stargard with Lychen and Wesenberg. The Wittmannsdorf Treaty. In ders .: History of the Land of Stargard up to 1471. Volume 1. Neustrelitz 1846, pp. 123–129. (Digitized version)

- ^ Georg Christian Friedrich Lisch : The Battle of Gransee in 1316 . In: Yearbooks of the Association for Mecklenburg History and Archeology, Vol. 11 (1846). P. 212 ff. ( Digitized version )

- ^ Hermann Krabbo : The transition of the state of Stargard from Brandenburg to Mecklenburg. In: Yearbooks of the Association for Mecklenburg History and Archeology. Volume 91 (1927), pp. 7-8. (Digitized version)

- ↑ a b c d e Cf. “ 3. Mecklenburg Land estates including knightly manors and rural towns ”, on: State Main Archive Schwerin: Online Find Books , accessed on February 1, 2017.

- ↑ Cf. “Mecklenburg”, in: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon : 20 vol., Leipzig and Vienna: Bibliographisches Institut, 1902–1908, Volume 13 'Lyrik - Mitterwurzer' (1906), pp. 499-508, here p. 501

- ↑ Helge bei der Wieden: Brief outline of the Mecklenburg constitutional history: six hundred years of Mecklenburg constitutions. State Center for Political Education Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Thomas Helms Verlag, Schwerin, 2001, ISBN 3-935749-07-4

- ^ Katrin Moeller: Mecklenburg - witch persecutions. In: Gudrun Gersmann; Katrin Moeller; Jürgen-Michael Schmidt [Hrsg.]: Lexicon on the history of the witch hunt at historicum.net , accessed on July 23, 2013

- ^ Helge bei der Wieden : Title and predicates of the House of Mecklenburg since the 18th century. In: Mecklenburgische Jahrbücher, Vol. 106 (1987), pp. 95-101.

- ↑ Andreas Pecar: Proceedings: Constitution and reality of life. The state constitutional inheritance comparison of 1755 in its time, Rostock 22. – 23. April 2005

- ^ Ingrid Mittenzwei : Friedrich II. Of Prussia. Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1980, p. 26.

- ↑ Ingrid Mittenzwei (ed.): Friedrich II. Of Prussia - writings and letters. P. 208f. Reclam, Leipzig 1987.

- ^ Ingrid Mittenzwei: Friedrich II. Of Prussia. Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1980, p. 118.

- ^ Ingrid Mittenzwei: Friedrich II. Of Prussia. Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1980, p. 133f.

- ↑ Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: Works, Volume 14, pp. 154-163 . Berlin 1974

- ^ Franz Mehring : On the history of Prussia. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1987, p. 189.

- ^ Michael North: History of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 3-40657-767-9 , p. 74.

- ^ Michael North: History of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 3-40657-767-9 , p. 76.

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Andreas Frost: Adolf Friedrich VI. In: Biographical Lexicon for Mecklenburg; Vol. 6. - Schmidt-Römhild, Rostock 2011, pp. 17-20 [here p. 18]. There are also numerous conspiracy theories about the circumstances of the death of the last Strelitz Grand Duke .

- ↑ "Frank's work, which is flush with the hereditary settlement in 1755, is indispensable because of its detail and many flowed from a good source documentary material for the Mecklenburg historians." (Quote from Walter Karbe of: Walter Karbe's cultural history of the country Stargard from the Ice Age to the Present. Published by Gundula Tschepego, Peter Schüßler on behalf of the city of Neustrelitz , Schwerin 2009, ISBN 978-3-940207-02-9 , p. 192.)