Klaus Mann

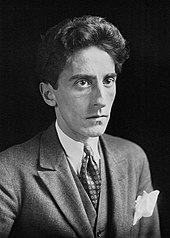

Klaus Heinrich Thomas Mann (born November 18, 1906 in Munich , † May 21, 1949 in Cannes , France ) was a German-speaking writer . Thomas Mann's eldest son began his literary career during the Weimar Republic as an outsider, as he dealt with topics in his early work that were considered taboo at the time . After his emigration from Germany in 1933, a major reorientation took place in the subject matter of his works: Klaus Mann became a combative writer against National Socialism . As an exile , he took American citizenship in 1943 . The rediscovery of his work in Germany did not take place until many years after his death. Today, Klaus Mann is considered to be one of the most important representatives of German-language exile literature after 1933.

Life

family

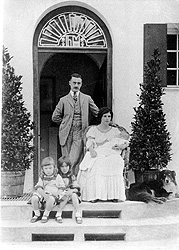

Klaus Mann was born as the second child and eldest son of Thomas Mann and his wife Katia in an upper-class family in Munich. His father had married the only daughter of the wealthy Pringsheim family from Munich and had already achieved great literary recognition with his novel Buddenbrooks . In the Mann family , Klaus Mann was called "Eissi" (or "Aissi"), originally a nickname of his older sister Erika for Klaus, which was later used in correspondence and Thomas Mann's diary.

Klaus Mann described his ancestry as “the bitterest problem of my life”, since his work as a writer was measured throughout his life by the work of his famous father, whose popularity on the other hand meant “that my name and the fame of my father, which one also means when one he thinks it made my first start easier. […] I have not yet found my impartial reader. ” Klaus Mann submitted his first publication at the age of 18 in 1924 in the weekly newspaper Die Weltbühne , however, under a pseudonym.

The relationship with his distant father was always ambivalent . Early on in his diary he complained that “Z.'s [Thomas Manns] are completely cold towards me.” However, Thomas Mann, who was called “magician” in the family, stated shortly after the death of his son Klaus:

- "How many speediness and lightness may be detrimental to his work, I seriously believe that he belonged to the most talented of his generation, was perhaps the most talented."

With his mother Katia Mann, called "Mielein", and especially with his sister Erika (called "Eri" in the family circle), however, he had a close relationship of trust, which can be seen in the numerous letters he wrote to her until his death .

Childhood and youth

Klaus Mann was born in Munich's Schwabing district, from 1910 the family lived at Mauerkircherstraße 13 in Bogenhausen in two connected four-room apartments to accommodate the family of six with the siblings Erika, Klaus, Golo and Monika as well as the house staff. In 1914 the family moved into the house called Poschi at Poschingerstraße 1 in Herzogpark.

The family mainly spent the summer months in the country house near Bad Tölz, built in 1908 . However, his father sold the Tölzer summer house during the war in 1917 in favor of a war loan. Elisabeth (“Medi”) was born in April 1918 and the sixth child of the Mann family, Michael (“Bibi”), was born a year later . Klaus Mann described the latest addition to the family in his second autobiography: "In view of the tiny creatures, we felt quite worthy and superior, almost like uncle and aunt."

In Klaus Mann's parents' house there were diverse cultural stimuli. Writers like Bruno Frank , Hugo von Hofmannsthal , Jakob Wassermann and Gerhart Hauptmann were guests, as well as the publisher Thomas Manns, Samuel Fischer . Neighbor Bruno Walter was general music director of Munich and introduced Klaus and his siblings to classical music and opera . Their parents read to them from world literature, and later their father recited from his own works. At the age of twelve, Klaus Mann read a book every day according to his own reports. His favorite authors at the age of sixteen were already discerning writers:

- "The four stars that dominated my sky at this time and to whom I still like to confide myself today shine in undiminished glory: Socrates , Nietzsche , Novalis and Walt Whitman ."

He also felt close to the poet Stefan George : “My youth revered the Templar in Stefan George, whose mission and deed he describes in the poem. Since the black wave of nihilism threatens to engulf our culture, [...] he comes on the scene - the militant seer and inspired knight. ”Later, however, he rejected the nationalist cult that was driven around the poet. The works of his father and those of his uncle Heinrich Mann , who would become one of his literary and political role models, also had a strong influence on his later writing.

From 1912 to 1914 Klaus Mann and his sister Erika attended a private school, the institute of Ernestine Ebermayer , and then the Bogenhausen elementary school for two years. Together with his sister and Ricki Hallgarten , the son of a Jewish intellectual family from the neighborhood, he founded an ensemble in 1919 that was named Laienbund Deutscher Mimiker . Other players in addition to the younger siblings Golo and Monika were friends of the neighboring children. The group existed for three years and staged eight performances, including Klaus Mann's play Ritter Blaubart from 1921. The performances took place in private; Those involved attached great importance to professionalism, for example having a make- up artist put on them . At that time he wanted to be an actor and wrote many exercise books with plays and verse. He confided in his diary: "I must, must, must become famous."

After elementary school, Klaus Mann switched to the Wilhelmsgymnasium in Munich. He was a mediocre to poor student and only performed very well at essay writing. He felt the school was "dull and meaningless - an annoying necessity". Outside of school, he stood out as the head of the notorious "Herzogpark gang" in the residential area through ambitious and sometimes malicious pranks. It consisted of the original members of the Mimiker , which, in addition to Ricki Hallgarten, also included Gretel and Lotte Walter, daughters of Bruno Walter. His parents then decided to go to boarding school . From April to July 1922 he and his sister Erika attended the Bergschule Hochwaldhausen , a reform school in the high Vogelsberg in Upper Hesse . Since the upper classes were dissolved because of the "anarchist" disobedience of the older students, Erika Mann returned to Munich, while Klaus introduced himself in Salem . There he made the impression of a "complacent, early matured and capable boy", and the free school community of the Odenwald School in Ober-Hambach by the reform pedagogue Paul Geheeb was recommended to his parents .

He attended the Odenwald School from September 1922 to June 1923 and left it at his own request, despite many positive experiences and new friendships, for example the one with Oda Schottmüller . There is some evidence that this is where he had his first homoerotic encounters. In his second autobiography he wrote that he fell in love with his classmate Uto Gartmann at the Odenwald School: “His forehead was smooth and cool. He was lonely and clueless about animals and angels. I wrote on a scrap of paper: 'I love you'. ”At the Odenwald School, he developed the self-image of an artist and an emotional outsider. This feeling is expressed, for example, in his letter to the esteemed founder and headmaster Paul Geheeb, to whom he wrote in parting: “I will be a stranger everywhere. A person of my kind is always lonely everywhere. ”Despite his sudden departure, he remained connected to the Odenwald School and its director. He initially returned to his parents' house and received private lessons in preparation for his Abitur, which he broke off in early 1924.

During the economic and political crisis of 1923, the year of inflation , the young generation had the feeling that they were losing their feet, the values of their fathers no longer mattered. In order to suppress the feeling of belonging to a "lost generation", Klaus Mann often stayed in cabarets and bars in Berlin and Munich and described his experiences in his diary:

- “Since the Schwabing pubs and studios didn't seem attractive to us, we formed our own little bohemian , a lively, if somewhat childish, circle. A young man named Theo [Theo Lücke, a young punter] financed our escapades; It was he who introduced us to the expensive restaurants and dancing, which until then we had only looked longingly from the outside. […] Theo arranged masked balls, sleigh rides at night, luxurious weekends in Garmisch or at Tegernsee. "

From Easter 1924 Klaus Mann spent several weeks with Alexander von Bernus , a friend of his father's, in the Neuburg Abbey near Heidelberg , where he worked on the volume of novels Before Life , on cabaret songs and poems. At the beginning of September, Klaus Mann followed his sister Erika to Berlin. At the age of 18 he got his first permanent job as a theater critic at 12 Uhr Blatt , but he only stayed a few months. From then on he lived as a freelance writer and lived without a permanent place of residence.

First successes

In June 1924 Klaus Mann became engaged to his childhood friend Pamela Wedekind , the older daughter of the playwright Frank Wedekind , who also had a close relationship with his sister Erika. The engagement was broken up in January 1928. Pamela Wedekind married Carl Sternheim in 1930 , the father of their mutual friend Dorothea Sternheim , known as "Mopsa".

His first play Anja and Esther , in which he dealt with topics from his boarding school, was premiered on October 20, 1925 in Munich and on October 22 at the Hamburger Kammerspiele . In Hamburg, Klaus and Erika Mann, Pamela Wedekind and Gustaf Gründgens appeared in the leading roles . “From the shores of the North Sea to Vienna, Prague and Budapest there was a big noise in the forest of leaves: poet children play theater!” The play was viewed as a scandal by the public because it addressed the lesbian love of two women. Despite all the criticism, "the poet children played in front of full houses."

Klaus Mann's first book was published in 1925, the volume of short stories Before Life , which was published by the Enoch brothers. In the same year he publicly acknowledged his homosexuality when he published the novel Der pious dance , which is considered one of the first so-called homosexual novels in German literature. It was created after his first major trip abroad in the spring of 1925, which had taken him to England, Paris , Marseille , Tunisia and back via Palermo , Naples and Rome . In the same year his father published the essay On Marriage , which described homoeroticism as "nonsense" and "curse". Thomas Mann was referring to his own homosexual tendencies, which he did not allow himself to act out and did not make public during his lifetime. The openly lived homosexual relationships of his children were tolerated by him, among other things, it was common for Klaus Mann to bring his partner into the parental home.

Klaus Mann led a restless life without a center of life. In 1925 he stayed frequently in Paris, where he met many French writers such as Jean Cocteau , whose work Les Enfants terribles he dramatized in 1930 under the title Geschwister . The poet André Gide , whom he saw as a kind of superfather, became his intellectual and moral model; However, the emotional closeness that was shown to him was not reciprocated by him. René Crevel , a surrealist writer, became his friend, and it was through Crevel that Mann met the Parisian surrealists. The initial sympathy for the artistic movement turned into aversion, which was reflected in the essays The Avant-garde - Yesterday and Today (1941) and Surrealist Circus (1943); The main reasons for this were the dogged communist politicization and the “leader cult” around André Breton , with which Mann connected the Crevel suicide in 1935.

Erika Mann married Gründgens on July 24, 1926. In 1927 Klaus Mann premiered his play Revue zu Vieren at the Leipziger Schauspielhaus under the direction of Gründgens and with the same cast as Anja and Esther and then went on tour with Erika and Pamela Wedekind. Due to the bad reviews, Gründgens feared for his reputation, played with the world premiere in Hamburg and Berlin, but did not join the tour from Cottbus to Copenhagen . Then the estrangement between Klaus Mann and Gründgens began.

In the essay Today and Tomorrow. Regarding the situation of the young, intellectual Europe , which appeared in 1927, Klaus Mann described his conviction that Europe must meet its peaceful and social obligations together. After his erotic topics, in which he had expressed “the love of the body”, there were self-critical comments for the first time that he had not followed the “social obligation” enough so far. He called for a policy of understanding, because this was the lesson from the bitter "error" of 1914, when most "intellectuals" fell into "triumphant madness instead of cursing it." In his essay he referred to Heinrich Mann's dictatorship Reason , Coudenhove-Kalergi Paneuropean concept and Ernst Bloch's socialist ideas of the spirit of utopia .

Together with his sister Erika, Klaus Mann set out on October 7, 1927, on a world tour lasting several months until July 1928, both of which led around the globe via the USA including Hawaii , Japan , Korea and the Soviet Union . Through their international acquaintances and the fame of their father, they gained access to many celebrities in the cultural scene such as Emil Jannings and Upton Sinclair . They also gave themselves the pseudonym The Literary Mann Twins and presented themselves as twins in order to attract further attention. Klaus and Erika Mann tried to finance their living by giving lectures, but the income was too low and after the trip they had high debts, which were paid by Thomas Mann after he had received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929 . The joint report on the world tour was published under the title All Around in 1929.

In 1929, Klaus Mann's Alexander appeared. A novel of utopia in which he traced the life story of Alexander the great . Compared to his first novel The Pious Dance , the language appears more functional, more concise. However, Mann remained a representative of the traditional, narrative writing style. Although he counted himself to a "lost generation", he did not follow the example of the American writers of the "lost generation " such as Gertrude Stein , Sherwood Anderson and Ernest Hemingway , who expressed themselves in short, simply formulated sentences.

The artist marriage of Erika Mann and Gustaf Gründgens did not last; on January 9, 1929 the divorce took place . Klaus Mann later used Gründgens as a template for his novel Mephisto , which appeared in Amsterdam in 1936 and which in 1971 led to a literary scandal in the Federal Republic of Germany due to the ban on republication, the so-called Mephisto decision .

In early 1930 Klaus and Erika Mann went on a trip to North Africa. In the city of Fez in Morocco, both of them had their first contact with the “magic herb hashish” through their guide. It was to become a “horror trip” for the siblings, which Klaus Mann later described in detail in his second autobiography. His drug use, from which he was never to be free, began at the end of 1929. He took morphine , as he told his sister. It is believed that Mopsa Sternheim's friend and later husband Rudolph von Ripper introduced him to drugs.

Harbingers of the Third Reich

The world economic crisis of 1929 helped the NSDAP to break through; In the Reichstag elections of September 14, 1930, the party received a huge increase in votes and was able to increase its seats in parliament from 12 to 107. Klaus Mann then publicly commented on current politics for the first time in a lecture to the Wiener Kulturbund in the autumn of 1930: "Anyone who was apathetic in politics until yesterday was shaken by the result of our Reichstag elections."

In the spring of 1932, his first autobiography , entitled Kind of this time , dedicated to Ricki Hallgarten, was published. It spanned the years 1906 to 1924. In the few months before Hitler came to power , the book found a wide readership, as the literary self-portrait of a famous son became a prominent figure Family with its anecdotes and revelations satisfied the curiosity of the reading public. Child this time was banned in 1933.

Also in 1932 the novel Treffpunkt im Infinite was published, it describes the life of young artists and intellectuals in Berlin and Paris immediately before Hitler came to power. In the stylized figure of the careerist, the protagonist Gregor Gregori is largely identical to that of Hendrik Höfgen in Mann's later novel Mephisto .

Klaus and Erika Mann, Ricki Hallgarten and their mutual friend Annemarie Schwarzenbach had planned a trip to Persia by car in the same year . On the eve of the trip, on May 5, 1932, Ricki Hallgarten shot himself in his house in Utting am Ammersee . A little later, Klaus Mann wrote his literary memorial for his childhood friend, the sensitive essay Ricki Hallgarten - Radicalism of the Heart .

European exile

With Hitler's appointment as Reich Chancellor, Klaus Mann became an active opponent of National Socialism and was involved in the cabaret Die Pfeffermühle , founded by Erika in early 1933 , which acted against National Socialism with its political-satirical program. To avoid arrest, he left Germany on March 13, 1933 and fled into exile in Paris . For him and his siblings, his parents' temporary residence in Sanary-sur-Mer became a meeting point with other German-speaking emigrants, such as Hermann Kesten and Franz and Alma Werfel . Other places during the first phase of emigration were Amsterdam and Küsnacht near Zurich, where the parents had rented a house.

On May 9, 1933, he wrote a letter to the once revered writer Gottfried Benn denouncing his positive attitude towards National Socialism. He accused Benn of making his name, once the epitome of the highest level, available to those "whose level of sophistication is absolutely unprecedented in European history and whose moral impurity the world turns away in disgust." Benn countered with an open "answer." die literary emigrants ”, which was broadcast by the Berliner Rundfunk and then printed on May 25 by the“ Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung ”, in which he denied emigrants the right to assess the situation in Germany accurately. Benn later admitted his wrong path and wrote in his book Doppelleben about the then twenty-seven year old, published in 1950, that he had "judged the situation more correctly, foresaw the development of things exactly, he was more clear-cut than me."

Mann's novel Der pious dance , like other of his works, was one of the books that were publicly burned by the National Socialists between May 10 and June 21, 1933 . In his diary on May 11th, he commented ironically: “So yesterday my books were publicly burned in all German cities; in Munich on the Königsplatz. Barbarism down to the infantile. But honor me. "

In August 1934, Klaus Mann attended the 1st All Union Congress of Soviet Writers in Moscow as a guest, but was the only invited writer to be more distant towards socialist teaching, unlike Willi Bredel , Oskar Maria Graf and Ernst Toller, for example . In September 1934 he signed an appeal against the reintegration of the autonomous Saar area into the German Reich . He was then expatriated at the beginning of November and initially had to travel as a stateless person with a Dutch alien passport. Mann remembers that the writer Leonhard Frank and the director Erwin Piscator were expatriated at the same time as he was.

As early as September 1933, Klaus Mann published the monthly literary magazine The Collection at Querido Verlag in Amsterdam. His friend Fritz H. Landshoff headed the newly founded German-language department of the Dutch publishing house, where many German exiles had their books published. According to Mann, after the death of Ricki Hallgarten, Landshoff was “the most beautiful human relationship I owe to those first years of exile.” Contributions to the magazine Die Sammlung were written by his uncle Heinrich Mann , Oskar Maria Graf, André Gide and Aldous Huxley , Heinrich Eduard Jacob and Else Lasker-Schüler . In August 1935, the collection had to be discontinued due to insufficient subscriber numbers despite financial support from Annemarie Schwarzenbach and Fritz Landshoff; Klaus Mann worked for months without pay. Some authors such as Stefan Zweig , Robert Musil , Alfred Döblin and his father Thomas Mann had refused to help or later distanced themselves from the magazine because the texts seemed too political to them and they feared disadvantages for their own work in Germany for this reason. The publisher Gottfried Bermann Fischer, for example, argued that anyone who wanted to continue to see their books published in Germany should not work on a magazine such as the collection that was banned in the Reich .

In the following years, Klaus Mann led an emigre life with alternating stays in Amsterdam and Paris, Switzerland , Czechoslovakia , Hungary and the USA. During this time three of his most important works were published: Flight to the North (1934), the Tchaikovsky novel Symphonie Pathétique (1935) and Mephisto (1936). The change of his former brother-in-law Gustaf Gründgens to a careerist as protégé Hermann Göring and cultural representative of the Third Reich had horrified him and inspired him to what is probably his most famous work. The protagonist Hendrik Höfgen as a follower resembles Diederich Heßling from Heinrich Mann's work Der Untertan , a 1918 satire on the Wilhelmine epoch . Klaus Mann had reread this novel while Mephisto was being written and recognized the terrifying, prophetic topicality of the work.

After his German citizenship was withdrawn , he - like other members of the Mann family - became a citizen of Czechoslovakia in 1937. Erika Mann had married the writer WH Auden as a second marriage in 1935 and thus obtained British citizenship. In Budapest Klaus Mann learned in the summer of 1937, shortly before his first opiates withdrawal, his perennial American partner, the film and literary critic Thomas Quinn Curtiss know, he in the same year Vergittertes window dedicated, an amendment to King Ludwig II of Bavaria. . His second withdrawal attempt took place in Zurich in April 1938. During the Spanish Civil War , he worked as a reporter for the Paris daily newspaper in June and July 1938 .

American exile

A year before the Second World War , he emigrated in September 1938 - like his parents - to the USA, which his sister Erika Mann had chosen as exile in 1937. Incest rumors arose about his siblings and denunciations of his homosexual relationships. From 1940 Klaus and Erika Mann's telephone and mail contacts were monitored by FBI officials , as both were suspected of being supporters of communism . It was not until 1948 that it became known that the FBI was keeping files on them.

Klaus Mann was often a guest at his parents' house in Princeton , and like Erika and other exiles, he often stayed in the "Hotel Bedford" in Manhattan , New York . Up to 1941, like Erika, he mainly went on lecture tours as a “lecturer” in various American cities in order to draw attention to what was happening in National Socialist Germany. Escape to Life appeared in 1939 . German culture in exile about personalities from the German cultural and intellectual scene in exile such as Albert Einstein , whose photo on the Rockefeller Center was the frontispiece . The title became a great journalistic success. Like The Other Germany , published in 1940, it emerged from a collaboration with Erika Mann. The first manuscript, which he wrote entirely in English and completed in August 1940, was Distinguished Visitors ; He portrayed famous European personalities such as Chateaubriand , Sarah Bernhardt , Antonín Dvořák , Eleonora Duse and Georges Clemenceau and reported on their experiences with the continent of America. The work did not find a publisher during its lifetime and was only published in a German translation in 1992.

Klaus Mann was editor of the anti-fascist magazine Decision from January 1941 to February 1942 . A Review of Free Culture . However, there were again too few subscribers for Decision , and despite intensive efforts, the magazine had to be discontinued after a year. He felt the failure of his project as a bitter defeat. In the summer of 1941, he attempted suicide for the first time. Christopher Lazare, the editor of Decision , was able to prevent the suicide.

Erika Mann was now working quite successfully at the BBC and lived with the doctor and writer Martin Gumpert . Klaus Mann wrote about Gumpert in his 1939 novel, Der Vulkan. A novel among emigrants when Professor Abel made a souvenir. 1942 his second autobiography was published The Turning Point (dt. The turning point ), written in English and later translated for a German edition. Klaus Mann was able to complete the German manuscript shortly before his death in April 1949. The autobiography Der Wendpunkt is, however, according to its own information in the post-comment of the German edition, not identical to the American edition; The turning point is more extensive and ends with a letter dated September 28, 1945, while The Turning Point concludes with a diary entry from June 1942. Some details from the American edition are not included in the turning point , which the German reader believes were unnecessary.

After the publication of the Turning Point , Klaus Mann began with a study on André Gide, André Gide and the Crisis of Modern Thought (German: André Gide and the crisis of modern thought ). This was followed by work on Heart of Europe , an anthology of European literature , together with Hermann Kesten . Both titles were published in 1943.

In the US Army

At the end of 1941, Klaus Mann joined the US Army in order to overcome his personal crisis and depression, to reduce debts and to fight even more actively against National Socialism. However, the draft after his voluntary report was delayed because of an unhealed syphilis and investigations by the FBI against him until December 14, 1942. He was shocked to learn about the racism in the American army in dealing with their colored soldiers, because they were called " nigger ”referred to and lived in a special district of the camp,“ a kind of black ghetto. ”He was stationed at Camp Ritchie for about a month in the spring of 1943 and was promoted to staff sergeant ; there he met Hans Habe and his friend Thomas Quinn Curtiss, among others . Like his comrades, Mann was then not allowed to leave the troop transport to land in Sicily ( Operation Husky ) in May 1943 , because at that time he had not yet been granted American citizenship.

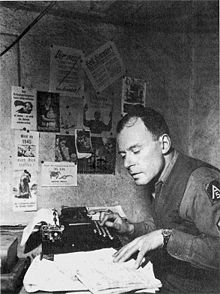

He received the "naturalization" on September 25, 1943, thus Klaus Mann was a citizen of the USA and left on December 24, 1943 with a troop transport of the 5th US Army . He was stationed first in North Africa , then in Italy . There he wrote, among other things, propaganda texts for the Allied forces. His application for release from the Army in August 1944 in order to be able to serve as a civilian with the Psychological Warfare Division , a subunit of the intelligence service OSS , in a liberated post-war Germany, was rejected, however, the current war situation did not permit a transfer to civilian status. As a German-speaking US Army soldier, one of his duties was to interrogate German prisoners of war , including hardened SS officers as well as unscrupulous, opportunistic or frightened young men in Wehrmacht uniforms ; many of them still clung to the military catalog of virtues. Then he evaluated the minutes of the conversation in order to find the right arguments for his educational work. It was encouraging for Klaus Mann when he met a prisoner like the Munich actor Hans Reiser , whom he considered an “anti-Nazi” and with whom he exchanged heartfelt letters after the war. From 1945 he published weekly articles in the Roman edition of the American army newspaper The Stars and Stripes .

Klaus Mann became Special Rapporteur for the Stars and Stripes in Germany after the end of the war . In this capacity he visited Munich at the beginning of May 1945, where he inspected the bombed-out family home and learned that the SS had set up a home for Lebensborn in the villa . In Augsburg, he and other journalists interviewed the Nazi politician Hermann Göring, who was awaiting trial . He visited and interviewed the non-emigrated composers Franz Lehár and Richard Strauss , the philosopher Karl Jaspers and the actor Emil Jannings, who was still known to him from the prewar period, and conducted an interview with Winifred Wagner in Bayreuth . In Prague he interviewed the Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš , whom he also knew from earlier times; Beneš had made him, his parents and siblings (with the exception of the British Erika) and Heinrich Mann citizens of Czechoslovakia after their expatriation.

On September 28, he was honored from the American Army. This was followed by changing stays in Rome, Amsterdam, New York and California. In autumn 1945, his first project after the war as a freelance writer was working on the script of Roberto Rossellini's neorealist film Paisà . However, the episode The Chaplain , which he wrote, was implemented very differently and his name was not mentioned in the opening credits of the film.

In 1945/46 he wrote the drama The Seventh Angel , a play that criticized belief in spirits and spiritism, but which was never performed.

Post War and Death

Klaus Mann could no longer feel at home in Germany; he recognized early on the prevailing atmosphere of repression. In an English-language lecture in 1947 he resignedly formulated:

“Yes, I felt a stranger in my former fatherland. There was an abyss which separated me from those who used to be my countrymen. Wherever I went in Germany, the […] nostalgic leitmotiv followed me: 'You can't go home again!' ”

“Yes, I felt like a stranger in my homeland. An abyss separated me from my former countrymen. Wherever I was in Germany, the [...] nostalgic leitmotif accompanied me: 'There is no return!' "

From 1948 Klaus Mann lived again in Pacific Palisades , California, in the house of his father , on whom he was financially dependent. He attempted suicide on July 11th, which the public learned about. He left home and stayed with various friends. In August his friend Fritz Landshoff got him a job as a lecturer at the Bermann-Fischer / Querido publishing house in Amsterdam, which merged in 1948, but where he only stayed for a few months. Increasingly he had writing difficulties. As he told his friend Herbert Schlueter, he found writing “more difficult than in the brisk childhood days. At that time I had 'a' language in which I was able to express myself very quickly; now I falter in two tongues. I will probably never be 'completely' at home in English as I 'was' in German - but probably no longer 'am' […] ”. He feared that he would no longer be in demand as an author. He was discouraged by the refusal of Georg Jacobi, managing director of Langenscheidt Verlag , to publish a contractually agreed new edition of the Mephisto , on the grounds: "Because Mr. Gründgens is already playing a very important role here."

He began his diary for 1949 with the words: “I am not going to continue these notes. I do not wish to survive this year ”-“ I will not continue these notes. I do not wish to survive this year. ”He suffered another serious disappointment in the spring, because he received from Querido Verlag, which was under Gottfried Bermann Fischer's direction after the merger , for the publication of the recently completed, revised and expanded version of the turning point in German , only evasive letters. In fact, Der Wendpunkt only appeared posthumously in Germany in 1952 at the urging of Thomas Mann.

At the beginning of April he moved to the “Pavillon Madrid” guest house (avenue du Parc de Madrid) in Cannes to work on his last, unfinished novel, The Last Day , which deals with the subject of suicide as a reaction to an imperfect world. From May 5th to May 15th he spent a few days on a detox in a clinic in Nice . On May 21, 1949, he died in Cannes after an overdose of sleeping pills . The day before he had written letters to Hermann Kesten and his mother and sister, in which he reported writing difficulties, money problems and depressing rainy weather. At the same time he mentioned planned activities for the summer. An interplay of various circumstances and causes such as the latent wish for death, political and personal disappointments and current external circumstances drove Klaus Mann to commit suicide.

Klaus Mann was buried in Cannes on the Cimetière du Grand Jas . His brother Michael was the only member of the family to attend the funeral. At the grave he played a largo by Benedetto Marcello on his viola . His parents and Erika were on a European lecture tour in Stockholm when the news of his death reached them. Together they decided not to break off the trip, but to stay away from social events. Erika Mann had a quote from the Gospel of Luke chiseled in his gravestone : “For Whosoever Will Save His Life Shall Lose It. But Whosoever Will Lose His Life […] The Same Shall Find It.” - “Because whoever wants to keep his life will lose it; but whoever loses his life […] will get it. ”Klaus Mann chose these words as the motto of his last novel The Last Day , which only exists as a fragment . A year later, the book Klaus Mann zum Gedächtnis was published by Erika Mann, with a foreword by his father and contributions from friends, including Max Brod , Lion Feuchtwanger and Hermann Kesten.

plant

Klaus Mann's biographer and chronicler Uwe Naumann remarks in the foreword of his photo and documentary volume There is no peace until the end of Klaus Mann's opposing facets: “In some respects he was ahead of his time by breaking conventions and rules. […] As modern and up-to-date as it is on the one hand, it was also firmly attached to many traditions. In some ways, Klaus Mann was and remained a 19th-century descendant. [...] The stylistic means, for example, which Klaus Mann used in his literary works, were often astonishingly conventional; and the verbose pathos found in many of his writings is now rather alien to us who were born later. It was not his business to formulate laconically; and it would not even have occurred to him to see something out of date in it ”. Naumann points out that Klaus Mann's printed writings comprise over 9,000 printed pages.

The plays

The theater performances of the “Lay Association of German Mimikers” from 1919 already bear witness to Klaus Mann's enthusiasm for the theater and his joy in presenting himself to the audience. Theater fascinated him because he saw a close connection between exhibitionism and artistic talent, “the deep pleasure of every artistic person in scandal, in self-disclosure; the mania of confession, ”as he wrote in childhood at that time . In total, Klaus Mann wrote six plays, which were rarely or never performed. However, his novel Mephisto , who viewed a theatrical subject critically, became very well known.

Mann's first published literary works include the pieces Anja and Esther (1925) and Revue zu Vieren (1926); both pieces show puberty problems and the desperate search for orientation. The performances attracted a lot of public attention and led to scandals, as the representation of homosexual and other unusual love relationships provoked the conservative public. Despite the bad reviews, Klaus Mann was “welcome as an advertisement” in the press. Both Anja and Esther and Revue zu Vieren show a pathetic way of expression and a not fully developed dramaturgy. Anja and Esther were ridiculed as a curiosity, while Revue zu Fieren was sharply criticized.

Across from China , his third play, which premiered in Bochum in 1930, is set in an American college and processed travel impressions from all around . The fourth play, Siblings , is a dramatization based on motifs from Cocteau's novel Les Enfants terribles . Siblings , which has an incest theme as content, turned out to be a successful adaptation of the Cocteau novel; however, this performance also became a scandal. The tenor of the criticism: The piece is “a work that is certainly felt to be real privately”, but it represents an “extravagant individual case”, not a social symptom. The Athens stage manuscript , written under the pseudonym Vincenz Hofer, was available as a stage manuscript at the end of 1932, but was no longer performed shortly before the seizure of power. Ten years later Mann conceived his last play under the title The Dead Don't Care ; he revised it in 1946 and named it The Seventh Angel . It was never performed either, but was given in a preliminary reading in Hamburg on the occasion of Mann's 100th birthday in early 2007.

Novels, autobiographies, short stories

Klaus Mann wrote seven novels and two autobiographies. Hermann Kesten made the appropriate remark that Klaus Mann often revealed more about himself in his novels than in his autobiographies. In fact, the autobiographies Kind This Time and The Turning Point [...] are to be read primarily as literary texts. […] The final chapter of the turning point, for example, […] by no means contains real letters, but fictitious correspondence: literarily reshaped texts that were created years after the specified letter dates.

The first book publication, which appeared in 1925, was the title Before Life , a volume with short stories. In the same year Der pious dance followed , published by Enoch Verlag in Hamburg, one of the first novels with autobiographical homosexual references. According to the travel book Rundherum, which was written together with Erika Mann in 1929, Alexander became in the same year . Novel der Utopie published, both first published by S. Fischer Verlag , the publisher of his father Thomas Mann. In 1932 Treffpunkt im Infinite was published , a novel in which he first used the technique of the stream of consciousness , inspired by James Joyce and Virginia Woolf . The first novel published in exile near Querido, Amsterdam, was Escape to the North in 1934 , followed by the Tchaikovsky novel Symphonie Pathétique (1935). His most famous novel Mephisto. A career novel followed a year later. At the same time as Escape to Life , his last novel was published in 1939, the émigré novel Der Vulkan . The stories like Before Life are today in the anthology Maskenscherz. The early stories contain, the late ones, in which, for example, the barred window was recorded, can be found in Speed. The stories from exile .

Binding of the first edition by Querido Verlag , Amsterdam 1934

Essays

The essays from the literary journals Die Sammlung and Decision as well as speeches and reviews as well as previously unpublished texts were summarized from 1992 onwards in the anthologies Die neue Eltern , Zahnärzte und Künstler , Das Wunder von Madrid , Zweimal Deutschland and Auf Lost Posten . The topics range from literary portraits and anti-fascist texts to political and aesthetic debates.

His last essay Europe's Search for a New Credo appeared a few weeks after his death in mid-June in the New York magazine “Tomorrow”, a month later in Erika Mann's translation under the title The Visitation of the European Spirit in the Zurich “Neue Rundschau”. There he stated the "permanent crisis of the century" that shook civilization to its foundations and called on intellectuals and artists to commit suicide together:

“Hundreds, even thousands, of intellectuals should do what Virginia Woolf , Ernst Toller , Stefan Zweig , Jan Masaryk did. A wave of suicide, to which the most eminent and celebrated spirits fell victim, would startle the peoples out of their lethargy, so that they would understand the deadly seriousness of the affliction that man has brought upon himself through his stupidity and selfishness [.] "

Diaries, letters

The existence of his diaries was not known until 1989. The six-volume edition, which was published in excerpts for the first time by Eberhard Spangenberg and taken over by Rowohlt Verlag, has been available in closed form since 1991. It not only offers informative information about Klaus Mann, but also bears testimony to literary and contemporary history up to the middle of the 20th century. In the diaries - unlike in his autobiographies - Klaus Mann noted the impressions of people, books and events openly and ruthlessly, they are therefore of great documentary value. They also provide undisguised information about his love life, the drug addiction, the one that can hardly be controlled Death wish, his hopes, dreams and nightmares and the difficult relationship with his father.

In the publication by Klaus Mann - Letters and Answers 1922–1949 , 362 letters from Klaus Mann and 99 answers in correspondence with family and friends document Klaus Mann in the context of his time and personality; an example is the correspondence with other writers such as Lion Feuchtwanger , Hermann Hesse and Stefan Zweig. The heart of the correspondence, however, is the correspondence with the father, Thomas Mann.

reception

"You know, Papa, geniuses never have brilliant sons, so you're not a genius."

Effect during lifetime

When the friendship with Klaus Mann still existed, Gustaf Gründgens wrote in Der Freihafen around 1925 : “The younger generation has found its poet in Klaus Mann. This should be noted above all. [...] Above all, one must love the poet of these people, who sends his characters so animated and painful through the exciting play [ Anja and Esther ] and does not - like most prophets today - leave them in the middle of a mess, but with a helpful hand leads to clarity. And that is the essence of Klaus Mann: He is not only a portrayal of the new youth, he is perhaps called to become their guide. "

Literary contemporaries in Germany did not spare criticism of Klaus Mann's early works, in which he wanted to portray himself as the spokesman for the youth: "A drama by Bronnen , a novel by Klaus Mann - they are like each other like a burst sewer pipe", Die joked Nice literature . Axel Eggebrecht described him as the leader of a “group of impotent but arrogant boys” and advised “ to leave us alone for five years.” Bertolt Brecht called “Kläuschen” a “quiet child who is back in the Blessed Grandpa's rectum is playing ”, and Kurt Tucholsky said:“ Klaus Mann sprained his arm while he was writing his hundredth advertisement and is therefore unable to speak for the next few weeks. ”Even when Klaus Mann was one of the first to tread the anti-fascist path , the critical voices did not fall silent. So far, little practiced in self-criticism, Mann took some reproaches to heart and learned in the next few years to formulate more consistently and theoretically more soundly.

Klaus Mann's first autobiography from the spring of 1932, child of that time - the author was just 25 years old - describes the period from 1906 to 1926. This work takes a step in the change of the author from a young dandy to a socially critical writer. The novel Meeting Point in Infinity , also published in 1932, was shaped by this new approach. The influence of modern novels like those of James Joyce , André Gide and Virginia Woolf influenced Mann to create this novel with different parallel storylines. This makes it one of the first modern educational and development novels in the German-speaking world, alongside Alfred Döblin's Berlin Alexanderplatz (1929) and Hans Henny Jahnn's Perrudja (1929).

The writer Oskar Maria Graf met Klaus Mann in 1934 at the 1st All Union Congress in Moscow and described him in his work Journey to the Soviet Union 1934 : “Clean, as if peeled from the egg, casual, elegantly dressed, slim and slim, so to speak, with a clever one , classy face, with nervous movements and a remarkably quick pronunciation. Everything about him seemed a little mannered, but it was dampened by a shrewd taste. The whole person had something restless, overheated intellectual and, above all, something strangely youthful. ”He was rather critical of Mann's works:“ What I had read of him so far betrayed the unprocessed style tradition that he had from his father and partly from Heinrich Mann had taken over, everything was still little original, flawless, but seedless. Only in the lightly written travel book All around have I found a hint of independence so far ”.

On the publication of Mann's novel The Volcano. The novel among emigrants in 1939, which the author considered his best book, was written by Stefan Zweig , who also lived in exile: “Dear Klaus Mann, I still have a personal feeling about this book - as if you were immunizing yourself with it and thereby yourself and saved. If I read correctly, you wrote it against an earlier self, against inner insecurities, despair, dangers: this explains its violence to me. It is not a book that has been observed, [...] but one that has been suffered. You can feel it. "

Klaus Mann was one of the few German emigrants who wrote larger works in English in exile. His first English stories were revised linguistically and stylistically by his friend Christopher Isherwood . After the work Distinguished Visitors , which was not published during his lifetime , he wrote his second autobiography The Turning Point entirely in English. The title refers to Mann's view that every person has the opportunity at certain points in life to decide for one or the other and thus to give his life a decisive turn. In his life it was the change from an aesthetically playful to a politically committed author. The American press received the Turning Point benevolently, as The New York Herald Tribune wrote in October 1942: “If you didn't occasionally fall into an inappropriate slang phrase in the polished prose, if you didn't taste a hint of German in its transcendentalism , The Turning Point would definitely have loved it may have been written by an American writer who had spent the twenties in Paris to return home to social awareness and the anti-fascist front. This is a kind of testimony to the international way of seeing, the overcoming of national borders, which the author declares in the final pages of the book to be the only goal that counts. "However, the sales figures did not correspond to the brilliant reviews, they could" no buyers for this Win a book, ”as Thomas Mann wrote regretfully to Curt Riess .

Klaus Mann - a modern author

Due to the strong influence of Thomas Mann on Gottfried Bermann Fischer, Thomas Mann's publisher, Der Wendpunkt was first published posthumously in 1952 by S. Fischer Verlag . This autobiography is an important contemporary document about the literary and art scene in Germany in the 1920s and the life of German intellectuals during exile in World War II.

The rediscovery of Klaus Mann after the Second World War is due to his sister Erika. She found the publisher in Berthold Spangenberg and in Martin Gregor-Dellin the editor for the republication of the first Klaus Mann work edition in separate editions in the Nymphenburger Verlagshandlung , from 1974 in the edition spangenberg in the Heinrich Ellermann publishing house . The new editions appeared between 1963 and 1992. The first volume was published in autumn 1963, 34 years after it was first published by Alexander. Novel of utopia . Rowohlt Verlag later continued this task. Public recognition of his achievements did not take place until after 1981, when Mephisto appeared in a new edition in West Germany, despite the still existing printing ban, and half a million copies were printed within two years. Today the novel is part of classic school reading. The successful new edition was preceded in 1979 by the dramatized version by Ariane Mnouchkine at the Théâtre du Soleil in Paris , followed by the film adaptation of Mephisto by István Szabó in 1981 ; both adaptations were very successful. In the meantime, all of Klaus Mann's literary work and almost all of his private correspondence and personal notes have been published.

Uwe Naumann , publisher of numerous first editions from the estate of Klaus Mann and biographer, wrote for the 100th anniversary of the author in the period November 16, 2006: "When Klaus Mann exacerbated in the spring of 1949 and lonely took his own life, he could hardly dream let that he would become a cult figure decades later, especially for young people. Where does the fascination come from? Klaus Mann once said of one of his fictional characters, the actress Sonja in Treffpunkt im Unendlichen (1932), that she was condemned to go skinless through this bustle , through the at once gruesome and alluring life of the big cities. The characterization also fits himself: he has lived his life strangely unhoused and unprotected, constantly on the move and wandering restlessly. The turning point ends with the following sentences: There is no rest until the end. And then? There is also a question mark at the end. Perhaps it is precisely the turmoil and fragility of its existence that defines its astonishing modernity. "

On the occasion of Klaus Mann's 100th birthday, the media scientist and author Heribert Hoven summed up under the heading “What remains of Klaus Mann”: […] “He represents the typical intellectual of the first half of the last century like few people. To this day, his experience is sorely lacking. They can, however, be obtained from his posthumous work, which Rowohlt Verlag has excellently edited. We missed his voice during the democratic new beginning in post-war Germany. In Adenauer's Greisenstaat and beyond, he would certainly have developed his fighter nature against the philistine idyll and for a bourgeoisie that is at home in the world. It was especially absent in the 1960s, when an idealistic youth once again put taboos and world revolution on the agenda. "

criticism

Klaus Mann was often criticized for his fast writing speed. This resulted in numerous careless mistakes in some works. For example, it was one of Hermann Hesse's criticisms of the novel Treffpunkt im Infinite that the protagonist Sebastian lived in hotel room number eleven, shortly afterwards it was number twelve. Thomas Mann commented on his son's writing speed that he had worked “too lightly and too quickly”, “which explains the various stains and negligence in his books”.

In his work, the focus of which is his novels Symphonie Pathétique , Mephisto and Der Vulkan , there are often autobiographical references, which earned him the accusation of exhibitionism . Marcel Reich-Ranicki wrote: “In everything that Klaus Mann has written, it is noticeable how strong his need to make confessions and confessions was from his early youth, how much he felt repeatedly urged to self-observation, self-analysis and self-expression. […] Almost all of his novels and short stories contain clear and usually only fleetingly disguised contributions to his autoportraits. [...] he apparently never had any reservations about projecting his own worries and complexes into the characters of his heroes without further ado ”.

In her biography about Klaus Mann, Nicole Schaenzler emphasizes his fears of attachment: "The many failed (love) relationships and obvious partner misconduct on the one hand, the devoted, sometimes with great effort, occupied with people like André Gide, René Crevel and - particularly serious - how one's own father consistently kept their distance, on the other hand - behind this there is also the drama of a deeply fearful person who has experienced affection and love above all ex negativo. Anyone who finds himself in such a vicious circle of conflicting feelings of longing and defense, who fears the abandonment of his inner being so much that he prefers not to get involved in a deeper relationship, will sooner or later avoid a real emotional commitment to the only possible (life) strategy. This pattern of behavior undoubtedly arises from the - unconscious - fear of being misunderstood, hurt and betrayed. [...] It is quite possible that this (self-) destructive avoidance strategy was not least the consequence of early childhood experiences and a difficult parent-son constellation. "

Klaus Mann's suicide

From his earliest youth, Klaus Mann was dominated by a feeling of loneliness and a longing for death. Death was aestheticized and glorified by him in private records and in his work. Reich-Ranicki attributes this to personal circumstances, because “[he] was homosexual. He was addicted. He was the son of Thomas Mann. So he was beaten three times. "

Other attempts at explanation see Klaus Mann's longing for death and thus his suicide especially in external circumstances, wrote Kurt Sontheimer on August 11, 1990 in Die Welt : “Klaus Mann said goodbye to the intellectual struggles of his time through his suicide - too early. But in his person he has given a great example of faith in the European spirit, which can be an example for us today. "

Heinrich Mann also summed up that his nephew Klaus was “killed by this epoch”, and Thomas Mann's conclusion was: “He certainly died on his own hand and not to pose as a victim of the times. But it was to a large extent. "

Golo Mann emphasized the latent wish for death of the brother in his memories of my brother Klaus : “A number of heterogeneous causes, griefs about politics and society, lack of money, lack of echo, drug abuse add up, but don't add up to the whole thing Was death. The tendency to death had been in him from the beginning, he never could or never wanted to grow old, he was finished; more favorable conditions at the moment would have extended his life, but only by a small amount. Nothing is explained with it, only something is established. "

Publications

Novels

- The pious dance . A youth's adventure book. Enoch, Hamburg 1925, ext. New edition Rowohlt, Reinbek 2004, ISBN 3-499-23687-7 .

- Alexander. Novel of utopia . S. Fischer, Berlin 1929, ext. New edition Rowohlt, Reinbek 2006, ISBN 3-499-24412-8 .

- Meeting point in infinity . S. Fischer, Berlin 1932, new edition Rowohlt, Reinbek 1998, ISBN 3-499-22377-5 .

- Escape to the north . Querido, Amsterdam 1934, ext. New edition Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek 2003, ISBN 3-499-23451-3 ; New edition Rowohlt, Hamburg 2019, ISBN 978-3-499-27650-7 .

- Symphony Pathétique . A Tchaikovsky novel. Querido, Amsterdam 1935, ext. New edition Rowohlt, Reinbek 1999, ISBN 3-499-22478-X ; New edition Rowohlt, Hamburg 2019, ISBN 978-3-499-27648-4 .

- Mephisto . Novel of a career. Querido Verlag, Amsterdam 1936, new edition Rowohlt, Reinbek 1981, revised new edition 2007, ISBN 978-3-499-22748-6 ; New edition Rowohlt, Hamburg 2019, ISBN 978-3-498-04546-3 .

- The volcano . A novel among emigrants. Querido, Amsterdam 1939, revised and expanded. New edition Rowohlt, Reinbek 1999, ISBN 3-499-22591-3 .

- The Last Day. 1949. The previously unpublished fragment was included in 2015 in the volume of essays Treffpunkt im Unendlichen: Fredric Kroll - a life for Klaus Mann , ed. by Detlef Grumbach, recorded for the first time. Swarm of men, Hamburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-86300-191-9 .

Stories, reports, essays

- Before life , stories. Enoch Verlag, Hamburg 1925 (today contained in Maskenscherz. The early stories ).

- Children's story, story. Enoch, Hamburg 1926 (ibid.).

- All around. A cheerful travel book . (With Erika Mann). S. Fischer, Berlin 1929. New edition Rowohlt, Reinbek 1996, ISBN 3-499-13931-6 .

- Adventure. Novellas. Reclam, Leipzig 1929.

- Looking for a way. Essays. Transmare Verlag, Berlin 1931.

- The Book of the Riviera (With Erika Mann). from the series: What is not in the "Baedeker" , Vol. XII. Piper, Munich 1931. New edition Rowohlt, Reinbek 2003, ISBN 3-499-23667-2 ; New edition Kindler, Hamburg 2019, ISBN 978-3-463-40715-9 .

- The collection . Literary monthly. (Edited by Klaus Mann under the patronage of André Gide, Aldous Huxley, Heinrich Mann.) Querido, Amsterdam. September 1933 - August 1935. New edition Rogner and Bernhard Verlag, Munich 1986 at Zweiausendeins. Two volumes. ISBN 3-8077-0222-9 .

- Barred window. Novella (about the last days of Ludwig II of Bavaria). Querido Verlag, Amsterdam 1937; then S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1960 (today included in Speed. The stories from exile. )

- Escape to Life. German culture in exile . (Together with Erika Mann). Houghton Mifflin, Boston 1939. New edition Rowohlt, Reinbek 1991, ISBN 3-499-13992-8 .

- The Other Germany. (Together with Erika Mann), Modern Age, New York 1940 ( full text in the Internet Archive ).

- Decision. A Review of Free Culture . Ed. by Klaus Mann. New York, January 1941-February 1942.

- André Gide and the Crisis of Modern Thought. Creative Age, New York 1943 (German: Andre Gide and the crisis of modern thought ). New edition Rowohlt, Reinbek 1995, ISBN 3-499-15378-5 .

- Heart of Europe. An Anthology of Creative Writing in Europe 1920–1940 . Ed. by Hermann Kesten and Klaus Mann. L. B. Fischer, New York 1943.

- André Gide: The story of a European. Steinberg, Zurich 1948.

- The visitation of the European spirit. Essay 1948. New edition by Transit Buchverlag 1993, ISBN 3-88747-082-6 (also contained in Auf Lost Posten , pp. 523-542).

Short stories, essays, speeches and reviews published posthumously

- Uwe Naumann (Ed.): Maskenscherz. The early narratives. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1990, ISBN 3-499-12745-8 .

- Uwe Naumann (Ed.): Speed. The stories from exile. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1990, ISBN 3-499-12746-6 . First complete collection of Klaus Mann's stories, some of which have not yet been published, from the years 1933 to 1943.

- Uwe Naumann, Michael Töteberg (ed.): The new parents. Articles, speeches, reviews 1924–933. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1992, ISBN 3-499-12741-5 . This includes: Ricki Hallgarten - Radicalism of the Heart.

- Uwe Naumann, Michael Töteberg (ed.): Dentists and artists. Articles, speeches, reviews 1933–1936. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1993, ISBN 3-499-12742-3 .

- Uwe Naumann, Michael Töteberg (ed.): The miracle of Madrid. Articles, speeches, reviews 1936–1938. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1993, ISBN 3-499-12744-X .

- Uwe Naumann and Michael Töteberg (eds.): Twice Germany. Articles, speeches, reviews 1938–1942. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1994, ISBN 3-499-12743-1 .

- Uwe Naumann, Michael Töteberg (Ed.): On a losing streak. Articles, speeches, reviews 1942–1949. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1994, ISBN 3-499-12751-2 .

- Klaus Mann: Distinguished Visitors. The American dream (first edition at edition spangenberg 1992). Translated from English by Monika Gripenberg, Rowohlt, Reinbek 1996, ISBN 3-499-13739-9 .

- Klaus Mann: The twelve hundredth hotel room. A reader. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2006, ISBN 3-499-24411-X .

Plays

- Anja and Esther . Play, 1925, ISBN 3-936618-09-7 (also contained in The Seventh Angel. The Plays )

- Review for four . Play, 1926 (ibid.)

- Across from China. Play, printed in 1929, premiered in 1930 (ibid.)

- Siblings. Play based on Cocteau 1930 (ibid.)

- Athens. Play, 1932, written under the pseudonym Vincenz Hofer (ibid.)

- The seventh angel. Drama, Zurich 1946 (ibid.) On January 21, 2007, The Seventh Angel was presented to the audience in a staged (original) reading at the Ernst Deutsch Theater in Hamburg . This piece has never been performed.

- Uwe Naumann and Michael Töteberg (eds.): The seventh angel. The plays. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1989, ISBN 3-499-12594-3

- Nele Lipp / Uwe Naumann (eds.): The broken mirrors: A dance pantomime . peniope, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-936609-47-9 . The dance piece, known only to experts, a fairy tale about Prince Narcissus from 1927, had its world premiere in June 2010 in the auditorium of the Hamburg University of Fine Arts on Lerchenfeld.

Autobiographies, diaries, letters

- Child this time . Autobiography. Transmare Verlag, Berlin 1932. Extended new edition, Rowohlt, Reinbek 2000, ISBN 3-499-22703-7 .

- The Turning Point: Thirty-Five Years in this Century. Autobiography. L. B. Fischer, New York 1942.

- The turning point . A life story. 1952. Extended new edition with text variations and drafts in the appendix, edited and with an afterword by Fredric Kroll . Rowohlt, Reinbek 2006, ISBN 3-499-24409-8 ; New edition Rowohlt, Hamburg 2019, ISBN 978-3-499-27649-1 .

- Joachim Heimannsberg (Ed.): Diaries 1931–1949. (Excerpts). Rowohlt, Reinbek 1990, ISBN 3-499-13237-0 . (The diaries are kept in the Klaus Mann Archive of Monacensia , Munich and, according to the family's orders, may not be published in full until 2010, but have now been released for research.) From May 2012, they will be digitally publicly available.

- Friedrich Albrecht (Ed.): Klaus Mann: Briefe . Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin and Weimar 1988, ISBN 3-351-00894-5 .

- Golo Mann, Martin Gregor-Dellin (Ed.): Letters and Answers 1922–1949. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1991, ISBN 3-499-12784-9 .

- Herbert Schlueter, Klaus Mann: Correspondence 1933–1949 . In: Sinn und Form 3/2010, pp. 370–403 (as an introduction: Klaus Täubert: Zwillingsbrüder, Herbert Schlüter and Klaus Mann . In: Sinn und Form 3/2010, pp. 359–369; and: Herbert Schlüter: From the Italian diary . In: Sinn und Form 3/2010, pp. 404–417).

- Gustav Regulator : Letters to Klaus Mann. With a draft letter from Klaus Mann . In: Sinn und Form 2/2011, pp. 149–176 (afterwards: Ralph Schock : “I liked the regulator again best.” Gustav Regulator and Klaus Mann. In: Sinn und Form 2/2011, pp. 177–183) .

- Rüdiger Schütt (Ed.): "I think we get along". Klaus Mann and Kurt Hiller - companions in exile. Correspondence 1933–1948. edition text + kritik, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-86916-112-9 .

- Inge Jens and Uwe Naumann (eds.): "Dear and revered Uncle Heinrich". Rowohlt, Reinbek 2011, ISBN 978-3-498-03237-1 .

Poems and chansons

Poems and chansons . Edited by Uwe Naumann and Fredric Kroll. With etchings by Inge Jastram. Edition Frank Albrecht, Schriesheim, 1999, ISBN 3-926360-15-1 (For the first time, all lyrical works are collected in this volume, including numerous previously unpublished texts from the estate; the spectrum ranges from the first childhood poems to the satires for the Cabaret "Die Pfeffermühle" by his sister Erika).

Film and theater

- Mephisto , made into a film by István Szabó with Klaus Maria Brandauer , 1980

- Meeting point in the infinite - Klaus Mann's journey through life , documentary by Heinrich Breloer and Horst Königstein , 1983

- Escape to the North , film adaptation by Ingemo Engström , 1985/1986

- The volcano , film adaptation by Ottokar Runze with Nina Hoss , 1998

- Escape to Life - The Erika and Klaus Mann Story , documentary by Andrea Weiss and Wieland Speck with Maren Kroymann and Cora Frost , 2000

- The Manns - A novel of the century . Multi-part television adaptation of the family history of Heinrich Breloer and Horst Königstein, 2001

- Dear uncle Heinrich - In the footsteps of Klaus and Heinrich Mann , by Thomas Grimm , with Inge Jens , Uwe Naumann , Zeitzeugen – TV, 45 min, 2011

- Mephisto , play by Thomas Jonigk based on Klaus Mann. World premiere at the Staatstheater Kassel , January 24th, 2020

new media

- Thomas Mann, Klaus Mann: Fathers and Sons. From letters, diaries and memories. Read by Will and Christian Quadflieg . Two audio CDs, Universal Music, Deutsche Grammophon Literatur 1995 series, ISBN 978-3-932784-49-1 .

- The turning point , reading with Ulrich Noethen , director: Petra Meyenburg , MDR / BR 1999 / der Hörverlag 2004, ISBN 3-89584-958-8 .

literature

- Friedrich Albrecht : Klaus Mann the intermediary: Studies from four decades. Lang, Bern 2009, ISBN 978-3-03911-744-4 . ( partly online ).

- Renate Berger : Dance on the volcano. Gustaf Gründgens and Klaus Mann. Lambert Schneider, Darmstadt 2016, ISBN 978-3-650-40128-1 .

- Eva Chrambach, Ursula Hummel: Erika and Klaus Mann. Pictures and documents. Edition Spangenberg, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-89409-049-9 .

- Hiltrud Häntzschel : Man, Klaus. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 16, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-428-00197-4 , pp. 51-54 ( digitized version ).

- Nadine Heckner, Michael Walter: Klaus Mann. Mephisto. Novel of a career. (= Series of King's Explanations. Volume 437). Hollfeld 2005, ISBN 3-8044-1823-6 .

- Samuel Clowes Huneke: The Reception of Homosexuality in Klaus Mann's Weimar Era Work . in monthly books for German-language literature and culture . Vol. 105, No. 1, Spring 2013. 86-100. doi: 10.1353 / mon.2013.0027

- Fredric Kroll (Ed.): Klaus Mann series of publications. 6 volumes. Blahak, Wiesbaden 1976–1996:

- Vol. 1: Klaus Blahak (preface); Fredric Kroll (preface); Bibliography . 1976.

- Vol. 2: 1906-1927, Disorder and Early Fame . 2006.

- Vol. 3: 1927-1933, Before the Flood . 1979.

- Vol. 4.1: 1933-1937, Collection of Forces . 1992.

- Vol. 4.2: 1933-1937, representative of exile. 1935–1937, Under the Sign of the Popular Front . 2006.

- Vol. 5: 1937-1942, Trauma America . 1985.

- Vol. 6: 1943–1949, Death in Cannes . 1996.

- Klaus Mann in memory. New edition with an afterword by Fredric Kroll, MännerschwarmSkript Verlag, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-935596-20-0 .

- Tilmann Lahme : The Manns. Story of a family. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2015, ISBN 978-3-10-043209-4 .

- Tilmann Lahme, Holger Pils u. Kerstin Klein: The men’s letters. A family portrait. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2016, ISBN 978-3-10-002284-4 .

- Uwe Naumann : Klaus Mann . Revised new edition, Rowohlt, Reinbek 2006, ISBN 3-499-50695-5 .

- Uwe Naumann (Ed.): There is no peace until the end. Klaus Mann (1906–1949) Pictures and documents. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2001, ISBN 3-499-23106-9 .

- Uwe Naumann: The children of the men. A family album. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2005, ISBN 3-498-04688-8 .

- Marcel Reich-Ranicki : Thomas Mann and his people. Fischer, Frankfurt 1990, ISBN 3-596-26951-2 .

- Nicole Schaenzler: Klaus Mann. A biography. Campus, Frankfurt / New York 1999, ISBN 3-593-36068-3 .

- Alexander Stephan : In the sights of the FBI. German writers in exile in the files of the American secret services. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 1995, ISBN 3-476-01381-2 .

- Carola Stern : On the waters of life. Gustaf Gründgens and Marianne Hoppe . Rowohlt, Reinbek 2007, ISBN 978-3-499-62178-9 .

- Armin Strohmeyr : Klaus Mann. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-423-31031-6 .

- Armin Strohmeyr: Klaus and Erika Mann. A biography. Reclam, Leipzig 2004, ISBN 3-379-20113-8 .

- Michael Stübbe: The Manns. Genealogy of a German family of writers. Degener & Co, 2004, ISBN 3-7686-5189-4 .

- Rong Yang: I just can't stand life anymore: Studies on Klaus Mann's diaries 1931–1949. Tectum, Marburg 1996; zugl .: Saarbrücken, Univ., Diss., 1995. (All friendships and relationships of Klaus Mann, as far as can be seen from the published parts of the diary, are registered, analyzed and commented on in this work.)

- Sabine Walter (Ed.): We are so young - so strange. Klaus Mann and the Hamburger Kammerspiele. Edition Fliehkraft, Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-9805175-5-1 .

- Bernd A. Weil: Klaus Mann. Life and literary work in exile. RG Fischer, Frankfurt 1995, ISBN 3-88323-474-5 .

- Andrea Weiss : Escape into life. The Erika and Klaus Mann story. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2000, ISBN 3-499-22671-5 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Klaus Mann in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Klaus Mann in the German Digital Library

- Stefan Kuhn, Kai-Britt Albrecht: Klaus Mann. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Short biography of the German Resistance Memorial Center

- Klaus Mann in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Diaries, letters, manuscripts, biographical documents from Klaus Mann online at: monacensia-digital.de

- Uwe Naumann : There is no peace. On the 100th birthday of Klaus Mann. in: Die Zeit No. 47, November 16, 2006

- Klaus Mann Initiative Berlin

- Klaus Mann on arts in exile

- Klaus Mann in the Bavarian literature portal (project of the Bavarian State Library )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Rainer Schachner : In the shadow of the titans . Königshausen & Neumann 2000, p. 67, accessed on December 16, 2010

- ↑ Klaus Mann: Child of this time. P. 251.

- ↑ Klaus Mann: Diary 3. p. 110.

- ↑ Preface to Klaus Mann in memory .

- ↑ Klaus Mann: The turning point. P. 101.

- ↑ Klaus Mann: The turning point. P. 144 f.

- ↑ Klaus Mann: The turning point. P. 158 f.

- ↑ Klaus Mann: The turning point. P. 112.

- ↑ Klaus Mann: The turning point. P. 102.

- ↑ Nicole Saddle Enzler: Klaus Mann. A biography. P. 30.

- ↑ Klaus Mann: The turning point. P. 166.

- ↑ Klaus Mann: Letters and Answers. P. 15.

- ↑ Klaus Mann: The turning point. P. 177 ff.

- ↑ a b Klaus Mann: The turning point. P. 224.

- ↑ Armin Strohmeyr: Klaus Mann. P. 130 ff.

- ↑ Klaus Mann: The new parents. P. 139.

- ↑ Klaus Mann: The turning point. P. 331 f.

- ↑ Fredric Kroll: Klaus Mann series of publications. Vol. 3, p. 81.

- ↑ Nicole Saddle Enzler: Klaus Mann. A biography. P. 184.

- ↑ Nicole Saddle Enzler: Klaus Mann. A biography. P. 211.

- ↑ Fredric Kroll in the epilogue to Meeting Point in Infinity. Reinbek 1999, p. 314.

- ↑ Hanjo Kesting: youthful magic and lust for death - Klaus Mann on his 100th birthday. Frankfurter Hefte, November 2006, archived from the original on October 11, 2007 ; Retrieved May 11, 2008 .

- ↑ Uwe Naumann: There is no rest until the end. P. 145.

- ↑ Nicole Saddle Enzler: Klaus Mann. A biography. P. 234.

- ↑ Nicole Saddle Enzler: Klaus Mann. A biography. P. 302.

- ↑ Klaus Mann: The turning point. P. 406.

- ↑ Klaus Mann: The turning point. P. 420.

- ↑ Uwe Naumann: There is no rest until the end. P. 154 f.

- ↑ Armin Strohmeyr: Klaus Mann. P. 117 f.

- ↑ Title page of the first issue as a photo, with a list of the 17 authors of this issue, in Eike Middell u. a., Ed .: Exile in the USA. Series: Art and Literature in Anti-Fascist Exile 1933–1945, 3rd Reclam, Leipzig 2nd Erw. and improved edition 1983, in the middle part without pagination (first 1979)

- ↑ Klaus Mann: The turning point. P. 609.

- ↑ Klaus Mann: The turning point. Pp. 623-631.

- ↑ Nicole Saddle Enzler: Klaus Mann. A biography. P. 475 f.

- ↑ Klaus Mann: The turning point. P. 413 f.

- ↑ Armin Strohmeyr: Klaus Mann. P. 140.

- ^ Klaus Mann: Letters and Answers 1922–1949. P. 603.

- ^ Klaus Mann: Letters and Answers 1922–1949. P. 798.

- ↑ Uwe Naumann: Klaus Mann. Reinbek 2006, p. 149.

- ↑ "Whoever loses his life will keep it". Retrieved December 27, 2016 .

- ↑ Uwe Naumann: There is no rest until the end. P. 326.

- ↑ Nicole Saddle Enzler: Klaus Mann. A biography. P. 520.

- ↑ chap. 9, verse 24.

- ↑ Uwe Naumann (Ed.): There is no peace until the end. Pp. 15-17.

- ↑ Klaus Mann: The seventh angel. Afterword, p. 419 ff.

- ↑ Klaus Mann: The seventh angel. Afterword, pp. 427-430.

- ↑ Uwe Naumann (Ed.): There is no peace until the end. P. 15.

- ↑ Nicole Saddle Enzler: Klaus Mann. A biography. P. 515 ff.

- ↑ Uwe Naumann (Ed.): There is no peace until the end. P. 14 f.

- ↑ Uwe Naumann: There is no rest until the end. P. 72.

- ↑ Thomas Theodor Heine : Thomas Mann and his son Klaus . In: Simplicissimus . 30th year, no. 32 , November 9, 1925, pp. 454 ( Simplicissimus.info [PDF; 8.4 MB ; accessed on May 21, 2019]).

- ↑ Uwe Naumann: Klaus Mann. P. 166.

- ↑ Nicole Saddle Enzler: Klaus Mann. A biography. P. 108 ff.

- ↑ Armin Strohmeyr: Klaus Mann. P. 55 f.

- ↑ Nicole Saddle Enzler: Klaus Mann. A biography. P. 307.

- ^ Klaus Mann: Letters and Answers 1922–1949. P. 385 f.

- ↑ Armin Strohmeyr: Klaus Mann. P. 127.

- ^ Afterword in Klaus Mann: The turning point. P. 865 f.

- ↑ Heribert Hoven: Life artist with a tendency to death - Klaus Mann on the hundredth birthday. literaturkritik.de, November 2006, accessed on May 11, 2008 .

- ↑ Neue Rundschau , May 1933 (vol. 64, no. 5, pp. 698–700)

- ↑ Thomas Mann: Letters 1948–1955 and gleanings. P. 91 f.

- ↑ Marcel Reich-Ranicki: Thomas Mann and his own. P. 192 f.

- ↑ Nicole Saddle Enzler: Klaus Mann. A biography. P. 144 f.

- ↑ Thomas Mann and his family. P. 202.

- ^ Heinrich Mann: Letters to Karl Lemke and Klaus Pinkus. Hamburg undated

- ↑ Thomas Mann: Speeches and essays 3. P. 514.

- ^ Helmut Söring: Klaus Mann - the tragedy of a son. Hamburger Abendblatt, November 15, 2006, accessed on May 11, 2008 .

- ^ Mephisto (WP) by Thomas Jonigk based on Klaus Mann , Staatstheater-kassel.de

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Man, Klaus |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Man, Klaus Heinrich Thomas |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 18, 1906 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Munich , German Empire |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 21, 1949 |

| Place of death | Cannes , France |