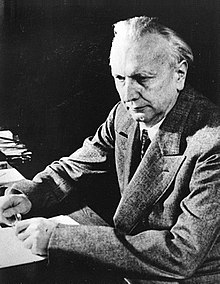

Karl Jaspers

Karl Theodor Jaspers (born February 23, 1883 in Oldenburg , † February 26, 1969 in Basel ) was a German psychiatrist and philosopher of international importance. He last taught at the University of Basel and became a Swiss citizen in 1967 .

As a doctor, Jaspers made a fundamental contribution to the scientific development of psychiatry . He is also considered an outstanding exponent of existential philosophy , which he strictly distinguished from Jean-Paul Sartre's existentialism . His philosophical work has an impact particularly in the areas of philosophy of religion , philosophy of history and intercultural philosophy . With his introductory writings on philosophy, but also with his critical writings on political issues such as the atomic bomb, the development of democracy in Germany and the debate about German reunification , he has achieved large print runs and has become known to a wider audience.

Relationships

Karl Jaspers was initially a teacher and then a lifelong friend of Hannah Arendt , with whom he had been exchanging letters for decades. He was also in correspondence with Martin Heidegger , which - interrupted during National Socialism - was only sparse after the Second World War . He had a long friendship with Max Weber , Hans Walter Gruhle and Kurt Schneider . He also maintained close contacts with Alfred Weber , Eberhard Gothein and Gustav Radbruch . Jaspers was part of the discussion group around Marianne Weber . After 1945 he played a key role in founding the University of Heidelberg and entered into a lifelong relationship with its first rector after the reopening, Karl Heinrich Bauer .

Life

childhood

Karl Jaspers was the son of the bank director and member of the state parliament Carl Wilhelm Jaspers (1850–1940) and his wife Henriette geb. Tantzen (1862–1941), the daughter of the Oldenburg state parliament president Theodor Tantzen the Elder . The Oldenburg Prime Minister Theodor Tantzen the Younger was an uncle of Jaspers. On his father's side, he came from a wealthy banking family, which he described as liberal-conservative. His great-grandfather had made an immense fortune through smuggling, but Karl's grandfather had been wasteful. Against this background, his parents taught him a sense of responsibility and critical thinking.

Karl Jaspers was a student at the old grammar school in Oldenburg.

From childhood, Jaspers suffered from bronchial problems (congenital bronchiectasis ), which severely impaired his physical performance and made him prone to infections. According to autobiographical evidence, strict discipline to maintain his health determined and limited his life, which, like that of his siblings, was also heavily burdened by family circumstances and sensitized him to psychological questions.

Studies and teaching

Jaspers studied the end of 1901 in Heidelberg and later in Munich three semesters jurisprudence . After a spa stay in Sils-Maria , he began studying medicine in Berlin in 1902 , which he continued in Göttingen from 1903 and in Heidelberg from 1906. Here, with the support of Karl Wilmanns , he received his doctorate on December 8, 1908 under Franz Nissl , the director of the Psychiatric University Clinic , who gave him the opportunity to work as a volunteer assistant from 1909 to 1914 after his license to practice medicine.

In 1907 Jaspers met Gertrud Mayer (1879–1974), who worked as an assistant in Oskar Kohnstamm's sanatorium . Gertrud was the sister of his college friend Ernst Mayer, who remained connected to him as an important conversation partner for decades. Gertrud and Ernst Mayer came from an orthodox German-Jewish merchant family. Karl Jaspers and Gertrud Mayer married in 1910. She was only able to survive the Nazi era thanks to this marriage in Germany.

Max Weber, whom he met in 1909 through Hans Walter Gruhle, became the scientific role model for Jaspers. In 1910/11 he temporarily took part in the working group on Freud's psychological theories and related views . His younger co-assistant Arthur Kronfeld had brought this group into being from the circle of the Göttingen philosopher Leonard Nelson due to years of exchange with his friend, the later Nobel Prize winner Otto Meyerhof . In addition to Gruhle, Meyerhof's colleague Otto Warburg and the medical student Wladimir Eliasberg , who later played an important role with Kronfeld in the great, Europe-wide psychotherapy movement of the 1920s, were also involved. Jaspers never mentioned this group, although he later himself called for a scientific justification of psychotherapy and critically examined psychoanalysis and its ideological claims until the end of his life .

On December 13, 1913, at the age of just thirty, Jaspers presented his textbook on general psychopathology as a habilitation thesis to Wilhelm Windelband at the Philosophical Faculty of Heidelberg University with the support of Nissl and Weber and was able to do his habilitation in psychology . With this writing, Jaspers left behind a work that still points the way when he switched to the philosophy of psychiatry , and which immediately found great recognition in the professional world. With his expansion of the psychiatric method arsenal to include the psychological- phenomenological method describing the symptoms of mental illness , Jaspers overcame reservations in brain research with what he called brain mythology and at the same time went well beyond Wilhelm Wundt's experimental-psychological approach , which Emil Kraepelin introduced to psychiatry before him would have.

During the First World War , Karl Jaspers' brother, Enno Jaspers, was in the stage. Karl Jaspers feared that due to his poor health he would still be drafted into the Landsturm without a weapon, which he was spared. During this time he corresponded with his brother Enno. After only two years teaching at the Philosophical Department of Heidelberg University, Karl Jaspers was appointed associate professor there in 1916. In 1920 he succeeded Hans Driesch and was promoted to associate professor . In the same year he began his friendship with Martin Heidegger, which lasted until he joined the NSDAP in May 1933. Mutual visits and a lively correspondence followed. Heidegger had recognized Jaspers' Psychology of Weltanschauungen in a major review and was very much influenced by this work. Since their elaboration of thinking about being was very different, the technical discussion was limited.

Jaspers became a full professor even faster: in 1921, negotiations to stay on account of appointments made to him led to a personal ordinariate being set up for him and he became co-director of the seminar alongside Heinrich Rickert in 1922. In terms of training and attitude, there was a considerable distance to Rickert, which was also reflected in both conceptions of philosophy. For Rickert - as a neo-Kantian , science- oriented philosopher - the calling of the non-specialist Jaspers with his psychological background, but above all his focus on the question of being , was difficult to accept. Due to the different assessment of performance and person of Max Weber, who was highly valued by Jaspers, there was an early personal break between Jaspers and Rickert.

In the following years Jaspers concentrated on an intensive and deep familiarization with the history and systematics of philosophy. First he read about the great philosophers and from 1927 began to work out his three-volume main work Grundriss der Philosophie , which he had developed from 1924 in lively exchange with his friend and brother-in-law Ernst Mayer. Hannah Arendt received her PhD from 1926–1928 with Jaspers. Their friendship began in 1932 and didn't end until his death.

Relationship to National Socialism

After the seizure of power, Jaspers still believed himself to be part of the Freiburg philosopher Martin Heidegger , who joined the NSDAP on May 1, 1933, in a kind of fighting community against the “decline of the university” which, as Jaspers put it, “had been for a hundred years slowly, quickly for thirty years ”. Long before 1933, Jaspers and Heidegger shared the view of the university as a place of upbringing and training for an aristocratic intellectual elite, which stood out from "massing" and from mere science management. On April 20, 1933 he wrote to Heidegger: “You are moved by the times - and so am I. It must be shown what is actually in it. "

In July 1933, a group of professors and lecturers was set up at Heidelberg University, including Jaspers, with the aim of drafting a new constitution for the universities in Baden based on the principles of the Nazi regime. Jaspers himself drafted a university constitution for this group based on the Führer principle , which only lags behind the then adopted constitution in one provision, but even goes beyond it in other provisions. In his ten "theses on the question of university renewal", he suggested that appointments should no longer be made by internal university appointment committees, but by a state representative. In detail, Jaspers' reform proposals showed clear differences to Heidegger. They emphasized the academic freedom that Heidegger made available, labor service and military sports ranked with Jaspers, in contrast to Heidegger, under the "essentially different discipline of intellectual work". The Volkish ideology was still missing from him . His “attitude to being oneself” was also aristocratic and elitist, but not authoritarian, but focused on communication among equals. The self-existent person “does not want allegiance, he wants companions”. However, on August 23, 1933, he welcomed Baden's new university constitution as an “extraordinary step” - “since I have known from my own experience how the previous constitution works [...], I can't help but find the new constitution right” - and he kept his own reform proposals “in line with the principles previously heard by the government”.

Contact with Heidegger broke off in the last months of 1933 after Heidegger's speech to the rectorate .

In the beginning, Jaspers suppressed the political realities. When Ernst Mayer prophesied to him in the summer of 1933 that the Jews would “one day be brought into barracks and set on fire”, he thought it was a fantasy: “That is quite impossible.” He let Hannah Arendt know that the whole thing was “one Operetta. I don't want to be a hero in an operetta. ”Her emigration seemed to him to be hasty“ stupidity ”. Jaspers had many arguments with Hannah Arendt about what he meant by his German nationalism . Arendt was able to understand Jaspers' Germanness , but she also pointedly reproached him for the fact that out of naive trust in the political maturity of his fellow citizens he was unable to recognize the threat of National Socialism. In 1914 he, like Max Weber, affirmed German power because he believed that Germany should become a third empire between Russian despotism and Anglo-Saxon " conventionalism " and "reflect the spirit of liberality, freedom and diversity of personal life, the greatness of Western tradition" represented. In contrast to Max Weber, however, he was always averse to Bismarck and the Prussian tradition and immediately after the defeat in 1918 thought that the nation-state was outdated and that Germany should ally itself with the West against Russia. In its change, however, the later experience under National Socialism played a decisive role.

Due to the measures taken immediately by the National Socialist rulers in 1933 to “ bring the universities into line ” in Germany, Jaspers was initially excluded from the university administration and at the end of September 1937 was forced to retire. Jaspers' wife was of Jewish descent. In 1938 an unofficial and from 1943 an official publication ban was imposed on him. In spite of this, Jaspers consistently continued his work and studies. Several times he thought of emigration and hoped for a call abroad. However, attempts made by friends failed. Due to the language barrier, in 1939 he turned down an invitation from Lucien Lévy-Bruhl as "Maître de recherches" at the "Caisse nationale de la Recherche scientifique" in Paris. In 1941, the University of Basel invited him to give guest lectures for two years. However, his wife was banned from leaving the country. Actually, he had decided to emigrate from within, in the name of belonging to a community of fate : “Nobody leaves his country without loss.” In exile, one runs the risk of falling into “bottomlessness”. Many longtime friends stood by him so he wasn't isolated. However, he was constantly under threat from the National Socialists, who wanted to deport him to a concentration camp on April 14, 1945 , but as he learned from a friend at the beginning of March. Jaspers had made provisions for this case and had potassium cyanide for himself and his wife ; However, he was spared using it because the US Army marched into Heidelberg on April 1, 1945.

post war period

After 1945, Jaspers was one of the most prominent scientists who contributed to the re-establishment and reopening of Heidelberg University. He was a member of the 13th Committee formed on April 5, 1945 with the approval of the American occupation authorities to rebuild the university. Personally highly respected by being elected Honorary Senator of Heidelberg University in 1946 and being awarded the Goethe Prize by the City of Frankfurt in the following year, but soon disappointed by further general and university policy developments in post-war Germany , Karl Jaspers accepted the call to Basel and changed in 1948 as successor to the chair of Paul Häberlin there . As a reaction to the election of former NSDAP member Kurt Georg Kiesinger as Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany and the passage of the emergency laws in 1968, Jaspers also acquired Swiss citizenship . He continued to issue highly regarded statements on contemporary issues as well as on scientific topics such as psychoanalysis. Karl Jaspers died in Basel in 1969 and was buried in the Hörnli cemetery.

Relationship to Arendt and Heidegger

After the end of the war in 1945, Jaspers was asked to submit a statement on Heidegger's work during the Nazi era. He recommended a temporary ban on teaching, which should be checked after the deadline. At the same time, he campaigned for a publication permit. Heidegger's subsequent ban on teaching ended on September 26, 1951.

His previous friendship with Heidegger was not resumed despite an exchange of letters. Heidegger wrote to Jaspers in 1950 that he was ashamed of the breakup during the Nazi regime: "I haven't come to your house since 1933 because a Jewish woman lived there, but because I was simply ashamed." Jaspers wasn't ready to revive the familiarity, however. The distance to the former philosopher friend can be found in the correspondence with Heidegger:

- “The endless mourning since 1933 and the current state in which my German soul is only suffering more and more have not united us, but tacitly separated us. The monstrosity, which is something completely different from just politics, has not allowed a corresponding word to be heard between us in the long years of my ostracism and life threat. As humans, we have moved a long way. "

Jaspers wrote to Hannah Arendt: “Can you as an impure soul - d. H. as a soul that does not feel its impurity and does not constantly push it out of it, but lives on thoughtlessly in the dirt - can one see the purest in insincerity? ”The form that Heidegger can identify is self-interpretation of being and time , as if he always wanted one and the same thing and did (September 1, 1949). To this Arendt replied: "What you call impurity, I would call lack of character." (September 29, 1949)

“I keep reading your Eichmann book. It's great for me, ”wrote Karl Jaspers to Arendt on November 2, 1963. Shortly thereafter, Jaspers began to write his own text: a book about Arendt and her way of thinking. His book about the student and friend remained unfinished. These fragments became publicly accessible for the first time in the exhibition mentioned below (autumn 2006).

Political statements

Even before the end of the war, Jaspers had noted in his diary: "Those who survive must be given a task for which they will consume the rest of their life." Jaspers saw the advocacy of freedom as a practical guide to his philosophy, because only in freedom one can really come to an illumination of existence. Jaspers drew the conclusion for himself to take a position on political life in the future.

He took the first step with the work Die Schuldfrage from 1946, which was also his first lecture at the University of Heidelberg, which he supported. Here he developed an understanding of guilt that still has a significant impact on political discussions today. He differentiated between criminal, political, moral and metaphysical guilt. The first to judge is for the courts, the second for the winner. But nobody can escape moral guilt, even if it is not decided in court. The responsibility remains. Only he can forgive who has been wronged . Jaspers now recognized the existence of God. It is a matter of God that man can become guilty at all. In the collective responsibility he included himself, who had to suffer from National Socialism and was existentially threatened:

- “We survivors did not seek death. We didn't take to the streets when our Jewish friends were taken away, we didn't scream until we were destroyed. We chose to stay alive with the weak, if correct, reason that our deaths could not have helped. It is our fault that we live. We know before God what deeply humiliates us. "

With this statement, Jaspers turned against the zeitgeist of repression and also demanded that each individual question their responsibility. At the same time he turned against the thesis of collective guilt : “But it is senseless to accuse a people as a whole of a crime. The individual is always a criminal. […] It is also senseless to morally accuse a people as a whole […] Morally, only the individual, never a collective, can be judged […] ”He continued to warn against offsetting any other political injustice. He also wrote in 1947: "It would be a disaster if important researchers had to leave who are burdened according to the scheme, but were always correct in word, writing and deed and after careful examination show no signs of National Socialist spirit".

In the period that followed, he repeatedly took a public position on the political situation. Together with Dolf Sternberger , he published the magazine Die Wandlung from 1946 to 1949 , in which prominent authors (Hannah Arendt, Bertolt Brecht , Martin Buber , Albert Camus , Thomas Mann , Jean-Paul Sartre , Carl Zuckmayer ) dealt with intellectual and moral issues call for political renewal. However, Jaspers was unable to implement his program of modernizing and, above all, democratizing the Heidelberg university constitution.

In 1958, his book The Atomic Bomb and the Future of Man , in which he opposed the formation of blocs and the suppression of freedom, received a lot of attention . Faced with the threat of a nuclear war, Jaspers saw not just the individual, but all of humanity in a borderline situation .

In his speech Truth, Freedom and Peace on the occasion of the award of the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in 1958, Jaspers dealt with the prerequisites for peace as world peace . There can be no external peace without the internal peace of states. “The violent struggle is extinguished in communication.” According to this, peace can only be achieved through freedom , both for the individual and, as a result, for the state. Democracy as a constitutional form alone is not enough.

According to Jaspers, freedom can arise from truth alone. This is what the philosophers have sought since ancient times. It does not lie primarily in the content, but in the type of discussion, in the "way of thinking of reason ". Although he rejects the Marxist regimes, he does not see the “politically free world” as really free. The only important thing there is producing and consuming, the goods are not durable, life is often empty and based on prestige. The statesmen have lost "touch" with the people. The historical knowledge of the population is inadequate, which is why he considers political education to be necessary.

"Our political freedom is not our merit, the lack of freedom in the East is not the fault of the Germans there [...] Both regimes are based on the will of the occupying powers." Due to the past, German self-confidence cannot relate to the political situation, but lies Unlike in Switzerland, for example, “in the community of pre-political substance, in the language, in the spirit and at home”.

His paper on freedom and reunification from 1960, in which he advocated accepting a separate state in the GDR , even if this could also restore freedom for this part of Germany , was received very critically . After a corresponding television interview, he was insulted as a “traitor to the fatherland” and “henchman of communism ”.

Jaspers nevertheless continued to seek controversy. He attended the Auschwitz trial as an observer and advocated the lifting of the statute of limitations for Nazi crimes that was imminent at the time . In 1966 he raised with the book Where is the Federal Republic drifting? Facts - dangers - opportunities warning his voice with a rejection of power politics and party state . He advocated a constitutional amendment in favor of more direct democracy . The people have very few opportunities to exert political influence. He described the elections as an " acclamation to the party oligarchy ". With these theses he got into the debate about the then grand coalition and the "self-betrayal" of the SPD in recognizing the emergency laws . He received criticism almost equally from politics from the right and left, but also met with broad approval from the public.

Awards

In 1947 Jaspers was elected a full member of the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences , from 1948 as a corresponding member, in 1953 he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Heidelberg, in 1958 the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade and in 1959 the Erasmus Prize as well as honorary doctorates from the Paris Sorbonne and the University of Geneva .

In 1947 Jaspers received the Goethe Prize from the city of Frankfurt , for which he gave the speech “ Goethe and our future”, in which he also dealt critically with Goethe. When Ernst Robert Curtius, in a polemic, rated this speech as presumptuous and inappropriate, the publicly held "Jaspers-Curtius controversy" developed. In general, Goethe was one of the leading figures in Jaspers' thinking. In an autobiographical self-examination in 1941, he wrote: “Goethe brought the atmosphere of humanitas and impartiality. To breathe this atmosphere, to love with him what really appears in the world, to touch the boundaries unveiled with him, but shyly touching it, was a relief in the unrest, became a source of justice and reason ”. In his speech, Jaspers problematized four issues under the question of Goethe's limits: “1. the rejection of modern natural science, 2. the harmonious basic conception of life and the world, 3. the abandonment of the unconditional in favor of the life-possible and 4. the premature resignation to something incomprehensible. ”To this end, he turned against an uncritical Goethe cult and demanded one "Revolution of Goethe Appropriation".

In 1958 Jaspers was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences . He retired in 1961. In 1962 his own university awarded him an honorary doctorate in medicine. In addition to numerous honorary memberships in other scientific societies, further awards followed: the Oldenburg Foundation Prize in 1963 (Jaspers refused to award an order in that year), the Pour le Mérite Order in 1964 and the Liège International Peace Prize in 1965 . In 1963 he was made an honorary citizen of the city of Oldenburg . A specialist hospital for psychiatry and psychotherapy is named after him in Oldenburg; There is also a bronze bust of Jaspers in the Cäcilienpark (illustration see below), and the Karl Jaspers Medal has been awarded since 2007 for services to culture in Oldenburg.

Jaspers was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950 and twice in 1960. a. by Erich Kästner .

The asteroid (48435) Jaspers was named after him.

plant

psychiatry

Karl Jaspers was among the first German psychiatrists of the 20th century to examine and reflect on the philosophical assumptions of their discipline. The pioneers of that time also included the psychiatrists Ernst Kretschmer ( Sensitive Relationship Mania , 1918), Arthur Kronfeld ( Das Wesen des psychiatrischen Erkennens , 1920), Ludwig Binswanger ( Introduction to the Problems of General Psychology , 1922) and others such as Otto Meyerhof , who under Recourse to the philosophy of Kant's successor, Jakob Friedrich Fries, as his friend Kronfeld tried to contribute to a scientifically sound foundation of psychiatry as early as 1910 with his contributions to the psychological theory of mental disorders .

Jaspers' Allgemeine Psychopathologie (1913) is considered to be the "beginning of methodically reflected psychopathological research" (Max Schmauß) - alongside Wilhelm Griesinger , who, according to Binswanger, gave "psychiatry its constitution" by describing "mental illnesses [as]" diseases of the brain '”As well as Emil Kraepelin , who was the first to introduce a useful nosological reference system in psychiatry.

Jaspers referred to Husserl's early work on descriptive psychology and Wilhelm Dilthey's much-discussed distinction between " explaining " and " understanding ", with which he supplemented psychopathology in methodological terms. The term “understanding”, for its part, is divided into that of “genetic understanding” and “static understanding”. While the static understanding serves the descriptive claim of psychopathology in the sense of creating a "finding", thanks to the "genetic understanding" one can empathize and recognize how "the soul emerges from the soul". In its delimitation, however, this also represents a method problem that is still being discussed today. Jaspers' assumption that certain psychopathological phenomena are characterized by the fact that they elude genetic understanding is still controversially discussed today. Jaspers himself later contributed nothing to this method problem, despite Kurt Schneider's emphatic request .

Jaspers placed particular emphasis on defining the limits of the psychopathological method. For this he described in detail "psychiatric prejudices" such as the so-called brain mythology , according to which the mentally ill are supposed to be brain ill. He also counted Freud's theoretical assumptions among the prejudices that should be combated in psychiatry.

He emphasized that mental processes are only accessible indirectly, namely through the communication of patients about their experiences. Reliable parameters for a mental disorder could not be derived from this, which means that psychopathological analysis differs fundamentally from scientific methods.

philosophy

Starting points

Important sources of the philosophy of Karl Jaspers are Kierkegaard , Spinoza , Nietzsche and above all Husserl and Kant , whom he reproached, however, for not grasping the dimension of interpersonal relationships , especially love . His philosophy is also heavily pervaded by life-philosophy elements. In a senseless reality, in which the natural sciences offer no help with self-assurance, people need an illusion-free view of their existence as the basis for their decisions to act.

His Psychology of Weltanschauungen from 1919 is a transition from psychology to philosophy and can be classified as the first work of modern existential philosophy. Jaspers was particularly interested in the mental impulses that give rise to world views. Already here he problematized the " borderline situations " such as death, suffering, guilt, historicity , which determine the experiences of man, at which he fails with rational thinking, and in which man can overcome skepticism and nihilism by presenting himself as existence towards the Becoming aware of transcendence . This book was for him

- “Only sense for people who begin to wonder, to reflect on themselves, to see the dubiousness of existence, and also only sense for those who experience life as personal, irrational responsibility that cannot be canceled” (preface).

The image of man in Jaspers' philosophy is shaped by a four-level mode of being as the dimensions of man's realization:

- biological existence as a ruthless, vital will to exist with interests in power, validity and enjoyment - at the same time the space of experience in which phenomenology and positivism find their limits;

- consciousness in general as a medium of objective thinking in the sense of the Kantian understanding (the ego), which determines the domain of logic ;

- the spirit as participation in holistic and meaningful ideas, which creates the connection in the dispersion of what can be known and experienced;

- Existence as what man can be, as a level of actual self- being that can no longer be empirically grasped, as a possibility of true human existence.

After a break in writing, which was devoted to intensive studies and preparatory work, Jaspers published in 1931 the 1000th volume of the Göschen Collection, the first purely philosophical work on the spiritual situation of the time , in which he was critical of topics of mass society , alienation and the rule of the Dealt with mechanization . Only in thinking that uses all expertise, but transcends this thinking, can humans be themselves and cope with the mass order of existence.

This fundamental work, which also warned against the seduction by Bolshevism and fascism , was a preliminary work for his three-volume major work published in 1932, which he simply called philosophy . The volumes are titled: I. Philosophical World Orientation ; II. Illumination of existence , III. Metaphysics . With this three-way division, Jaspers adopted the classic philosophical structure of questions about the cosmos , the soul and God.

Philosophy, a science?

For Jaspers, philosophy was not a science, but rather an illumination of existence that deals with being as a whole . Seen in this way, every utterance on philosophy is itself philosophy. Philosophy occurs where people wake up. Philosophy is the awareness of one's own powerlessness and weakness. Jaspers thereby distinguished scientific truth from existential truth . While the one is intersubjectively comprehensible, one cannot speak of knowledge with the other , since it is directed towards transcendent objects ( God , freedom ). Science knows progress , in his view philosophy does not.

- “We can hardly say that we are further than Plato. Only in the material of the scientific knowledge that he uses are we further. In philosophizing itself we have hardly come back to him. "(Introduction, 9)

Jaspers opposed the mixing of philosophy as he understood it with a philosophy that wants to compete with science and restrict itself to its methods. This makes herself the maid of science. He commented on Husserl's “Philosophy as Strict Science” as “a masterpiece also in its consistency that does not shrink from absurdity”. And he held up against the language-analytical philosophy of Carnap :

- “The illogical in grammar is to a large extent an expression of truths that defy formal logic. The formal logic is only one of the frameworks of language, not absolutely valid, even if it is essential. The consideration of language from the point of view of formal logic recognizes language only as sign language and has the tendency to purify language until - in the loss of its life - it is only sign language. "(Truth, 447)

Science is methodical knowledge, on a hypothetical basis necessarily certain and generally valid in the sense of intersubjectivity . But it has its limits in the absolute, in the insurmountable endlessness and the inaccessibility of the unity of the world. Science is limited to existence, consciousness in general and the mind . But existence remains undetected by science.

The recognizability of the world as a whole is a superstition , as it is given in Marxism , psychoanalysis and racial theories . With these, sociology , psychology and biological anthropology have been transformed into world views and thus become the "afterimage of philosophy". In this assessment he was closer to Popper than ever.

According to Jaspers, there is no external point of view for philosophy from which one can survey, compare or define it: “Truth, the correctness of which I can prove, exists without myself. […] The truth from which I live is only because I become identical with it. ”(Faith, 11). The object of philosophy is outside of object knowledge. For this reason philosophy has a problem of communication. It can only address its object indirectly and grasp it only by transcending it.

Existence - transcendence - the encompassing

Existence and transcendence are not objective for Jaspers. Being itself cannot be shown as an object, just as little as the ego through which objects are constituted. Only to the extent that man finds himself is man existence. The transcendent encounters the human being in ciphers. By this he does not mean, as one might think, secret signs or symbols, but rather thought experiences that convey to people that which cannot be materially grasped (e.g. code of transcendence: God - the one; code of nature: universe). Although ciphers remain “in the balance”, they give off powerful impulses.

Existence is always directed towards the other. Being a self essentially requires communication with other people. In communication from person to person, philosophy is realized in the “loving struggle”, in which attack and justification do not serve to gain power , but rather people come close to one another and give one another up. In this way one achieves the “awareness of being”, the “illumination of love” and the “perfection of calm”.

In the writing Reason and Existence (1935), Jaspers introduced his key term “the encompassing”, which is reflected in the existence of man as well as in the transcendence of the whole of the world without man ever being able to grasp it in its entirety. In his work Von der Truth (Volume 1 of Philosophical Logic), published in 1947, he developed these ideas further. When it comes to the term transcendence, Jaspers differentiated between the actual transcendence and the transcendence of all immanent modes of the encompassing: “We transcend to every immanent encompassing, i. H. we transcend definite objectivity in order to perceive what encompasses it; It would therefore be possible to call every form of the [immanent] encompassing a transcendence, namely in relation to everything tangible objectivity in this encompassing. ”(p. 109)

He also called the actual transcendence the transcendence of all transcendence as well as the encompassing par excellence or the encompassing of the encompassing; for him it is the real being (p. 108). In his philosophical faith (see the following section “Philosophical Faith and Revelation Religions”) he uses the term transcendence in a third meaning, namely as a synonym for God (including in Chiffren der Transcendenz , p. 43). The actual transcendence for its part is no longer encompassed, either on its own or together with immanence, since it is itself the all-encompassing. It encompasses the following modes of encompassing:

- the immanent modes of the encompassing:

- a) existence,

- b) consciousness in general,

- c) mind,

- d) world;

- the transcendent modes of the encompassing:

- a) the transcendencies that are not the actual ones, thus the transcendence of the immanent modes of the encompassing, and the transcendence (God),

- b) existence.

The encompassing according to 1 a) to c) and according to 2 b), i.e. existence, consciousness, spirit and existence, Jaspers also referred to as the encompassing that we ourselves are or can be, the encompassing of the actual transcendence and the world as the encompassing that is being. Transcendence (God) can obviously neither be the encompassing that we (human beings) are, nor the encompassing that is being, since God is not being but a being; it must therefore be viewed as an encompassing one of its own. Jaspers calls them “the other” (Chiffren der Transzendenz, p. 99).

Existence is "being able to do before transcendence." (The phil. Faith in view of Revelation p. 119) Elsewhere, Jaspers speaks of "devotion to transcendence". (Von der Truth, p. 79) It animates the immanent and realizes the encompassing that I myself am. It is not his, but his ability; she always has a choice of whether to be or not. “You have to decide about yourself. I am not only there, am not only the point of a consciousness in general, am not only the place of spiritual movements and spiritual production, but I can be myself in all of these or be lost in them. "( Von der Truth , p. 77) Strictly speaking, it is not “existence” that decides, but rather the person: If he finds himself and his freedom in existence, consciousness in general and spirit and becomes aware of his reason in transcendence, then being is realized for him of existence, otherwise for him there is only existence, not existence. Jaspers' concept of existence, which always speaks only of “possible existence”, is therefore different from that used by Heidegger , who defined existence as the “form of being” of human beings.

Jaspers saw reason as the unifying element of all ways of encompassing, as the will to unity, as movement without a secure continuity, as limitless openness. The ways of the encompassing cannot be objectified.

- "From every way of the encompassing that we are, not only from consciousness in general, to which the compelling insight belongs, but from existence, spirit and existence a peculiar sense of truth grows." (Existential philosophy, p. 29)

According to Jasper, the truth of existence is pragmatic truth, is that which is useful in life. The truth of consciousness in general is truth in the objective nature of the sciences, especially in mathematics. Truth in spirit is knowledge of the idea. Existential truth is based on communication with the other and is tied to personal accomplishment. As the various concepts of truth show, the modes of the encompassing cannot be reduced to one another and must be implemented in the sense of wholeness.

The existence of man is determined by freedom, which can neither be proven nor refuted, but which constantly places man in decision-making situations and reveals itself in his life's practice. Through freedom man chooses himself. Being self also includes communication in relation to others. "Nobody can be saved alone."

On the way to oneself, people come across borderline situations. He learns that with the questionable nature of the factual scientific world orientation he is reaching the abyss of the utterly incomprehensible. In death , struggle , suffering and blame the impasse is to prevent failure. Only by “accepting” this situation can a person come to his “real” existence.

Jaspers' philosophy has often been called irrational . But this is again disputed with the following arguments. On the one hand, Jaspers had a consistently positive relationship with the natural sciences and rational philosophy. On the contrary, he ( problematic from an epistemological point of view) gave the sciences unexamined unquestioned validity ( accountability and outlook ). On the other hand, his philosophy is conceived from the perspective of the free individual who - in communication with others - has to find his own ideas and ways of acting for himself. In this respect, Jaspers was at no time an ideologist who claimed absolute truth for his philosophy.

His basic question about the whole of being and the illumination of existence begins where all questions of scientific knowledge and reason are answered and no longer help. His answers are not metaphysical 'speculation', but show the openness of the decision and the responsibility of people in their freedom. His philosophical approach is forward-looking in contrast to Heidegger's, for whom he held an ontological fixation on the existentials.

Jaspers' philosophy also distinguishes itself from the nihilism of existentialism in that it makes the individual aware of his possible self-confidence in the illumination of existence and calls on him to take responsibility in freedom. In particular, the ideas of man's disgust with himself or the condemnation of freedom in Sartre are alien to Jaspers, even if the relationship to existentialism can be found in many thoughts. Freedom without reference to transcendence is not possible for him.

Philosophical Belief and Revelation Religions

Jaspers has, such as B. Aristotle , the Neoplatonists , ar-Razi and Spinoza, developed an elaborate philosophical belief in God. Belief in God is an essential part of a more comprehensive philosophical belief, which he founded in 1948 in The Philosophical Faith , 1950 in Introduction to Philosophy , 1961 in his last lecture Chiffren der Transcendenz and 1962 in The Philosophical Faith in the Face of Revelation . He expresses it in the following sentences (Introduction, p. 83):

- God is.

- We can live under God's guidance.

- There is an unconditional requirement in existence.

- Man is imperfect and cannot be completed.

- Reality in the world has a vanishing existence between God and existence.

- To 1

- “Only those who start from God can look for him. A certainty of God's being, no matter how germinal and incomprehensible it may be, is a prerequisite, not the result of philosophizing. ”(The philosophical belief, p. 33). For Jaspers, God is the only imperishable reality, but it cannot be proven (Introduction, p. 49). It is impossible to imagine what God is (Der philosophische Glaube, p. 34). Therefore, whatever we put before our eyes with regard to God, be nothing or just like a veil (Introduction, p. 46). Reference to the Old Testament “no image and no parable”. The numerous images, ideas and encounters with God contained in the OT are for Jaspers only ciphers of transcendence, necessary as a starting point for the search for God, but transcendent to be overcome in order to arrive at pure faith (lecture ciphers of transcendence), in which God is only present as “the slightest consciousness” (Introduction, p. 47). For Jaspers, belief thus retreats to a minimum at the limit of unbelief (Der philosophische Glaube, p. 23).

- To 2

- Guidance by God takes place on the way of freedom of action when man hears God. God's voice lies in that which people gain in self-assurance when they are open to everything that comes to them from tradition and the environment. However, humans never find God's judgment unequivocally and definitively: Nobody knows with an objective guarantee what God wants, hence the risk of failure (Der philosophische Glaube, p. 63 f. And introduction, p. 66-68).

- To 3

- In everyday life, our behavior is determined by purposes (conditions) that result from our interests in existence, but also by obedience to authorities (introduction, p. 53). “Unconditional actions [on the other hand] occur in love, in struggle, in taking on high tasks. A characteristic […] of the unconditional is that action is based on something against which life as a whole is conditioned and not the ultimate. ”(Introduction, p. 51). Unconditional is a freedom that cannot do otherwise. "Unconditionality becomes [...] temporally evident in the experience of borderline situations and in the risk of becoming unfaithful." (Introduction, p. 57). It is the choice between good and bad. To be good means to place life under the condition of what is morally valid, in the event of a conflict also against one's own happiness and existence interests (Introduction, p. 58).

- To 4

- Jaspers speaks of the “fundamental fragility of man”, of powerlessness, weakness and failure.

- To 5

- “A myth that - in biblical categories - thinks of the world as the appearance of a transcendent story: from the creation of the world to apostasy and then through the steps of salvation to the end of the world and to the restoration of all belongs to the vanishing world existence that takes place between God and existence Things. For this myth, the world is not of itself, but a temporary existence in the course of a transcendent event. While the world is something disappearing, the reality in this disappearing is God and existence. ”(Introduction, p. 82)

There is no statement from Jaspers from which it could be concluded that he also believed in life after death. For him, eternity is not an incessant duration, but the fulfilled moment.

Philosophical belief must be clearly distinguished from the religions of revelation: every revelation, according to Jaspers, is finitude already formulated by man. Confessing, in the form of an absolute truth, separates people, opens the abyss of lack of communication and restricts the truth of others. Revelation religions are therefore allowed to proclaim, but not expect others to follow their beliefs (The philosophical belief in the face of revelation, p. 534).

Philosophical belief is possible as a philosophical reflection without cult, without personifying prayer and without religious community (see also natural theology on this topic ). There is no security for this kind of belief, it is dependent on the innermost, where “transcendence can be felt or it (man) does not.” (P. 527) Jaspers assumes that the possibility of belief in revelation is also possible of human freedom, although it has long been used as a means of political power (p. 532.) The connection between philosophical belief and revelation belief consists in the fact that “it can happen to those who stand on one side to find one's own faith questionable in the face of the other ”(p. 534.) Although there is no simultaneity of the two modes of thinking in the same person, there is unlimited respect for the other person. "Every historicity can love the other in its existential seriousness and know that it is connected to it in an overarching way." (P. 536)

ethics

Jaspers rejected explicit ethics as a housing for world views because he did not want to see individual freedom of choice restricted in principle. But the possibility of human self-realization is a necessary condition for actual self-being, which constitutes the guideline for practical action. The whole philosophy of Jaspers is intended to illuminate existence. In this respect, philosophy is never just descriptive, but always appellative. (Philosophy II, 433) One achieves one's own enlightenment of existence through "inner appropriation", "serenity in knowledge", "deep serenity", "openness to oneself and others" and "bravery" ( philosophy II. Borderline situations). It is reason that shows the way to individual self-realization and brings out moral and political attitudes such as “honesty”, “truthfulness”, “altruism” or “willingness to take responsibility” (especially in: Von der Truth ). For Jaspers, the highest moral principle is the principle of the good, which is based on love and which people who want to remain true to themselves understand as "unconditional" (unconditional, not guided by considerations of usefulness). (see previous section "Philosophical Belief").

History and world philosophy

While the historicity of the human being in his self-becoming has always been an element of the basic understanding of human existence for Jaspers, he turned more and more to questions of the history of philosophy as a constituent element of a Philosophia perennis (statements about universally valid truths) , especially after 1945 can never be fully realized. Philosophy does not arise from the purity of independent intuition, but always from - mostly unnoticed and unchecked - assimilation and guidance of already existing concepts. The awareness of historicity is a prerequisite for existential philosophizing.

The dialogue, the communication with the "great" philosophers opens a space for philosophizing, in which one comes into a conversation about fundamental questions, which makes it possible to acquire the thinking of these outstanding persons of the history of philosophy and to develop one's own thinking. It does not depend on the historicizing retelling, but on the relationship to one's own existence. The authority of great works makes it possible to rediscover one's own origin.

Jasper's studies on the great philosophers are not historical works - this is often criticized - but rather philosophical discussions within the framework of an overall view of the respective thinking. "Philosophy concerns us as itself in its power, which comes to us through the great philosophers, not as historical knowledge of it." Historically, philosophy is only a report on a chain of errors.

Jaspers picked out a small group of "great" philosophers and ranked their importance:

- "The authoritative people": Socrates , Buddha , Confucius , Jesus ,

- "The continuing founders of philosophizing": Plato , Augustin , Kant ,

- “Metaphysicians who think from the origin”: Anaximander , Heraclitus , Parmenides , Plotinus , Anselm , Spinoza , Laotse , Nagarjuna .

Aristotle , Thomas and Leibniz are missing , who, according to Jaspers, do not lead to the heart of philosophy and thus do not bring about any transformation of “self-confidence”.

From his consideration of these great philosophers, Jaspers developed the idea of the Axial Age and the origin of philosophy from at least three sources: China, India and Greece. This insight as well as the world situation developing into a unified community through technology, especially traffic technology of modern times, led Jaspers to the idea of a world philosophy , i.e. an early discussion of the consequences of globalization .

- "Today we are looking for the ground on which people from all religious backgrounds can meet in a meaningful way across the world, ready to reappropriate, purify and transform their own history, but not divulge it." (Revelation, p. 7)

Universal communication as an illuminating existential encounter is possible through a tiered approach. It includes:

- the comparison with which one recognizes the common as well as the foreign;

- understanding as participation in the other;

- the common struggle for the truth (as “question, objection, refutation, questioning, listening, staying oneself”);

- appropriation, d. H. Change with expansion and profit on both sides.

Jaspers' philosophy is existential philosophy, philosophy of the encompassing and at the same time even more. It is not a philosophy of being or being, but a philosophy of the possibility of existence, openness and responsibility, which - coming from historicity - as a world philosophy at the same time opens the perspective for an intercultural philosophy.

Jaspers rejected the ascription that he had designed a new philosophy. He always emphasized that his philosophy only includes what emerges from the current time as a way of the history of philosophy.

- “The multiplicity of philosophizing, the contradictions and the mutually exclusive claims to truth cannot prevent something from working that no one has and around which all serious endeavors revolve at all times: the eternal one philosophy, the philosophia perennis.” (Introduction, p . 17)

reception

Karl Jaspers' work comprises over 30 books with around 12,000 printed pages and a legacy of 35,000 sheets with several thousand letters. Most of the works have been translated internationally. Jaspers' works, especially his introductory writings and the works on the history of philosophy, reach a total German-language circulation of more than a million copies.

There are Jaspers companies in Japan (since 1951), North America (since 1980), Austria (since 1987), Poland (since 2009), Italy (since 2011), Croatia (since 2011) and Germany / Oldenburg (since 2012). There is a Karl Jaspers Foundation in Switzerland , the aim of which is to promote an edition of the collected works and writings, including the estate and correspondence. Since 1990 the University of Oldenburg has held the annual Karl Jaspers lectures on questions of time . The University of Heidelberg, together with the City of Heidelberg and the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences, awards the Karl Jaspers Prize . In 2009, the University of Oldenburg was able to acquire Karl Jaspers' working library with around 12,400 units from the University of Basel (H. Saner) with financial help from EWE .

Hans Saner , Jaspers' former assistant, took care of the publication of the estate . Since 2012, the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences has been producing a complete edition of the works as well as a selection edition of the correspondence and the estate. Jeanne Hersch was particularly committed to spreading his thoughts in French-speaking countries . Contrary to the acceptance by the general public, one finds significantly less attention in the professional philosophy for the work of Jaspers. This can be attributed to the fact that his philosophy evades usual structures. Jeanne Hersch writes about this:

- “For the wicked he is a believer, for the believer an unbeliever, for the rationalists a mystic, for the mystics an indecisive rationalist. [...] Anyone who depends exclusively on logical and empirical evidence puts his 'borderline situation', 'ciphers', 'existence', 'transcendence', 'all around' in the fog of dark and reactionary talk. "

Otto Friedrich Bollnow used Jaspers' philosophy for education. Gerardus van der Leeuw's religious phenomenology is significantly influenced by Jaspers. Helmut Fahrenbach created connections between the concept of reason in Jaspers and the concept of communicative reason in Jürgen Habermas . A particular focus of the discussion about Jaspers is his "world philosophy". For this purpose, his approach of the "Axial Age" is also valued as a forerunner of intercultural philosophy . Current Jaspers researchers include Hans-Martin Gerlach , Kurt Salamun , Leonard H. Ehrlich and Richard Wisser, as well as Hermann Horn in the field of education . In the English-speaking world, Jaspers is partially classified as a religious philosopher.

Jaspers' book on the "question of guilt" has received severe criticism at times. In particular his thesis, only as a “close friend” “among fellow destinies, today among Germans”, one has the right to moral reproaches in the face of National Socialism, was interpreted as restitution of the national community and exclusion of the voice of the victims. Heinrich Blücher wrote to Hannah Arendt on July 15, 1946: “This whole ethical cleansing babble leads Jaspers to show solidarity in the German national community even with the National Socialists instead of in solidarity with the degraded ... This whole discussion of guilt is playing itself out very much in the face of God, a trick that finally allows even moral judgments to be forbidden to those who do not want to embrace Messrs. Lumpen directly in loving communication. ”This criticism is also formulated less sharply by representatives of today's historical science .

In 1964, Theodor W. Adorno understood Jaspers' style of language and philosophy in a polemical way as a prime example of a “jargon of authenticity” , an aristocratic tendency, the affirmation of religion, regardless of which, and the refusal to provide critical information about capitalist-negative reality give, inherent: “The radical question becomes substantial at the expense of any answer; Risk without risk "

Fonts (selection)

-

Homesickness and Crime (= Archive for Criminal Anthropology and Criminology , Volume 35), Vogel, Leipzig 1909, OCLC 600804588 (Dissertation University of Heidelberg 1908, 116 pages).

- Homesickness and Crime , with essays by Elisabeth Bronfen and Christine Pozsár (= Splitter , Volume 21), Belleville, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-923646-61-5 (Partly dissertation University Heidelberg 1909, [total] 184 pages).

- General psychopathology. A guide for students, doctors and psychologists. Springer, Berlin 1913; 4th, completely revised edition: Berlin / Heidelberg 1946; since then numerous other unchanged editions, ISBN 3-540-03340-8 .

- Psychology of worldviews. Springer, Berlin 1919, ISBN 3-540-05539-8 . ( Table of contents ; PDF; 275 kB)

- Max Weber. Speech at the memorial service organized by the Heidelberg student body on July 17, 1920 . Mohr, Tübingen 1921.

- Strindberg and van Gogh. Attempt of a pathographic analysis with comparative use of Swedenborg and Holderlin. E. Bircher, Leipzig 1922 (131 pages).

- The idea of the university. Springer, Berlin 1923; New version 1946; further new version, “designed for the current situation” , with Kurt Rossmann , 1961, again 2000, ISBN 3-540-10071-7 ( English translation ).

- The spiritual situation of the time. Berlin / Leipzig 1931; 5th edition 1932, ISBN 3-11-016391-8 .

- Max Weber. German being in political thinking, research and philosophizing. Stalling, Oldenburg iO 1932 (under the title Max Weber. Politiker, Mensch, Philosopher. Storm, Bremen 1946; with a new foreword: Piper, Munich 1958).

- Philosophy. 3 volumes (I .: Philosophical World Orientation ; II .: Existence Enlightenment ; III .: Metaphysics ). Springer, Berlin 1932, ISBN 3-540-12120-X .

-

Reason and existence. Wolters, Groningen 1935.

- English edition: Reason And Existence [sic!]. Five lectures. (Based on the third German edition by J. Storm, Bremen 1949) Translation with introduction by William Earle. The Noonday Press, place of publication 1955 ( to be read here in electronic form on the Internet Archive portal ).

- Nietzsche. Introduction to understanding his philosophizing . Springer, Berlin 1936, ISBN 3-11-008658-1 .

- Descartes and Philosophy . Springer, Berlin 1937, ISBN 3-11-000864-5 .

- Nietzsche and Christianity . Verlag der Bücherstube Fritz Seifert, Hameln [1938].

- Existential philosophy. Three lectures . de Gruyter, Berlin 1938.

- The question of guilt . Lambert Schneider, Heidelberg 1946.

- People and University. In: The change. Volume 2, 1947, pp. 54-64.

- From the truth . Munich 1947 ( English translation ).

- Philosophical Belief. Five lectures . Munich / Zurich 1948 (held in 1947 as guest lectures in Basel)

- From the origin and destination of the story. Munich & Zurich 1949 (representation of the Axial Age ) ( English translation ).

- Introduction to philosophy. Twelve radio lectures . Zurich 1950, ISBN 3-492-04667-3 . ( audio )

- Reason and unreason of our time. Three guest lectures . Munich 1950.

- Accountability and Outlook. Speeches and essays . Munich 1951.

- The question of demythologizing . Munich 1954 (see articles on Rudolf Bultmann and Fritz Buri ).

- Schelling. Greatness and doom . Munich 1955. ( Review )

-

The great philosophers . Piper, Munich 1957, ISBN 3-492-11002-9 .

- English edition: The great Philosophers . Published by Hannah Arendt. Translated by Ralph Manheim . Harcourt, Brace & World, New York 1962, 1966; Hart-Davis, London 1962 (from this the chapter Plato and Augustine ).

- The atom bomb and the future of man . Munich / Zurich 1957, ISBN 3-8302-0310-1 .

- Philosophy and world. Speeches and essays . Munich 1958.

- Truth, freedom and peace. Together with Hannah Arendt in: Karl Jaspers. Speeches on the award of the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade. Piper, Munich 1958 (with Arendt's laudation by Jaspers. This online, see web links)

- Freedom and reunification . Munich 1960, ISBN 3-492-11110-6

- Philosophical Faith in the Face of Revelation . Piper, Munich 1962, ISBN 3-492-01311-2

- Nikolaus Cusanus , Munich 1964.

-

Small school of philosophical thought . Thirteen-part lecture series, FRG 1964 (lectures held in the 1st trimester of the Bavarian television study program in autumn 1964); Sound recordings from the original audio tapes left behind are available in the form of CD and audio DVD.

- Published in book form: Piper, Munich 1965, ISBN 3-492-20054-0 .

- Hope and concern. Writings on German Politics 1945–1965 . Munich 1965.

- Where is the Federal Republic going? Facts, dangers, opportunities . Munich 1966, with an introduction by Kurt Sontheimer ( No. 1 on the Spiegel bestseller list from June 13 to October 16, 1966 )

- To the criticism of my work “Where is the Federal Republic drifting?” . Munich 1967.

- Philosophical essays . Fischer-Bücherei, Frankfurt am Main 1967, DNB 457094222 (249 pages, carton ).

- Fate and will. Autobiographical writings . Munich 1967.

- Complete edition. Volume 21: Writings on the university idea . Edited by Oliver Immel; Verlag Schwabe, Basel 2016, ISBN 978-3-7965-3423-2 .

From the estate:

- Ciphers of Transcendence . A lecture from 1961, Munich 1970, ISBN 3-8302-0335-7 .

- Kant. Life, work, effect . Munich 1975.

- What is philosophy Munich 1976.

- Philosophical autobiography . (New edition expanded by one chapter on Heidegger) Piper, Munich 1977.

- Notes on Martin Heidegger . Munich 1978.

- The great philosophers. Nachlass , Vol. 1. Munich 1981.

- The great philosophers. Nachlass , Vol. 2. Munich 1981, ISBN 3-492-02732-6 .

- World history of philosophy (introduction). Munich 1982.

- Truth and probation. Philosophizing for Practice. Munich / Zurich 1983.

- Correspondence 1945–1968. KH Bauer & Karl Jaspers , ed. by Renato de Rosa. Springer, Berlin a. a. 1983 ISBN 3-540-12102-1

- Correspondence 1926–1969. Hannah Arendt & Karl Jaspers , ed. by Lotte Koehler. Piper, Munich / Zurich 1985. ISBN 3-492-02884-5

- Correspondence 1920–1963. Martin Heidegger & Karl Jaspers , ed. by Walter Biemel, Hans Saner. Piper Klostermann, Munich Frankfurt am Main 1990. ISBN 3-465-02218-1

- Estate on Philosophical Logic , ed. by Hans Saner. Piper, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-492-03458-6 .

- Renewal of the university. Speeches and writings 1945/46 , ed. by Renato de Rosa. Lambert Schneider, Heidelberg 1986 ISBN 3-7953-0901-8 .

- The risk of freedom. Collected essays on philosophy , ed. by Hans Saner. Piper, Munich / Zurich 1996 ISBN 978-3492038485 .

- Correspondence. Three volumes: Psychiatry / Medicine, Philosophy, Politics / University ; Edited by M. Bormuth, C. Dutt, D. von Engelhardt, D. Kaegi, R. Wiehl u. E. Wolgast; Wallstein, Göttingen 2016.

- Matthias Bormuth (Ed.): Life as a borderline situation: A biography in letters . 1st edition. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2019, ISBN 978-3-8353-3430-4 .

Audio book

- Matthias Buschle (ed.), Karl Jaspers: The ciphers of transcendence. The farewell lecture on July 3, 1961. Christoph Merian Verlag, Basel 2011, ISBN 978-3-85616-456-0 .

exhibition

The Literature Archive in Marbach showed from September 28 until November 26, 2006. its holdings, the exhibition Karl Jaspers: The book Hannah. The exhibition referred to the time around 1930, when nine young people met in Marburg who will be among the most important intellectuals of the 20th century: Karl Löwith , Gerhard Krüger , Hans-Georg Gadamer , Leo Strauss , Hans Jonas , Erich Auerbach , Werner Krauss , Max Kommerell and Hannah Arendt . Hans Saner and Richard Wolin accompanied the exhibition with a conference about this Marburg group.

literature

Philosophy bibliography : Karl Jaspers - Additional references on the topic

- Otto Friedrich Bollnow : Explanation of existence and philosophical anthropology (Link to PDF; 171 kB) . Attempt to argue with Karl Jaspers. Blätter für Deutsche Philosophie Vol. 12 (1938), pp. 133-174. Reprinted in: Karl Jaspers in the discussion , ed. by H. Saner, Munich / Zurich 1973, pp. 185–223

- Matthias Bormuth : Karl Jaspers and the Psychoanalysis (Series Medicine and Philosophy. Articles from Research , Volume 7), Fromann-Holzboog, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 2002; ISBN 3-7728-2201-0 ; engl. Lifeconduct in Modern Times . Karl Jaspers and Psychoanalysis. Springer, New York / Berlin 2006 (review in Der Nervenarzt , Issue 7, 2004).

- Burkhart Brückner: Historicity and topicality of the theory of madness in general psychopathology by Karl Jaspers , in: Journal for Philosophy & Psychiatry: jfpp-2-2009-03

- Andreas Cesana / Gregory J. Walters (eds.): Karl Jaspers, historical reality with a view to the basic questions of humanity . Contributions to the 5th International Jaspers Conference, Istanbul, 10. – 16. August 2003. Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-8260-3938-6 .

- Knut Eming / Thomas Fuchs: Karl Jaspers. Philosophy and psychopathology . Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2007, ISBN 978-3-8253-5352-0 . review

- Dietrich von Engelhardt and Horst-Jürgen Gerigk (eds.): Karl Jaspers at the intersection of contemporary history, psychopathology, literature and film . Mattes, Heidelberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-86809-018-5 .

- Brea Gerson: Truth in Communication: On the origin of the existential philosophy in Karl Jaspers . Ergon, Würzburg 2004, ISBN 978-3-89913-330-1 .

- Johann Jakob Grund: Karl Jaspers. Its development between 1945 and 1950 (PDF; 167 kB) . In: Contradiction No. 18 Restoration of Philosophy after 1945 (1990), pp. 69–73

- Jeanne Hersch (Ed.): Karl Jaspers. Philosopher, doctor, political thinker. Symposium on the 100th birthday in Basel and Heidelberg. Piper, Munich a. a. 1986, ISBN 3-492-10679-X .

- Gunter Hofmann : Politics and Ethos in Karl Jaspers. Doctoral thesis under Dolf Sternberger . Heidelberg 1968.

- Albrecht Kiel: The language philosophy of Karl Jaspers, anthropological dimensions of communication. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2008, ISBN 978-3-534-21957-5 .

- Alan M. Olson (Ed.): Heidegger and Jaspers. Temple University Press, Philadelphia 1993.

- Klaus Piper (Ed.): Karl Jaspers. Work and effect. Festschrift for the 80th birthday. Piper, Munich 1963

- Renato de Rosa: The new beginning of the university 1945. Karl Heinrich Bauer and Karl Jaspers . In: Semper Apertus. Six Hundred Years of Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg 1386–1986, Vol. 1–6, ed. by Wilhelm Doerr u. a. Springer, Berlin a. a. 1985, here Vol. 3, pp. 544-568. ISBN 3-540-15425-6

- Renato de Rosa: Political Accents in the Life of a Philosopher. Karl Jaspers in Heidelberg 1091-1946. In: Karl Jaspers: Renewal of the University. Speeches and writings 1945/46. Edited by Renato de Rosa and Lambert Schneider, Heidelberg 1986, pp. 301-447 ISBN 3-7953-0901-8 .

- Kurt Salamun : Karl Jaspers . 2nd Edition. Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg 2006, ISBN 978-3-8260-3253-0 .

- Hans Saner : Karl Jaspers. With testimonials and photo documents. 12th edition. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-499-50169-4 .

- Hans Saner: Karl Jasper's Paths of Thought - A Reading Book . R. Piper, Munich / Zurich 1983, ISBN 3-492-02839-X .

- PA Schilpp (ed.): The Philosophy of Karl Jaspers . Tudor, New York 1957.

- Werner Schüßler : Karl Jaspers for an introduction. Junius, Hamburg 1995, ISBN 3-88506-914-8 .

- Reinhard Schulz / Giandomenico Bonanni / Matthias Bormuth (eds.): "Truth is what connects us". Karl Jaspers' art of philosophizing . Wallstein, Göttingen 2009, ISBN 978-3-8353-0423-9

- Chris Thornhill: Karl Jaspers: Politics and Metaphysics . Routledge, London 2002 ( also a review by Alan M. Olson ).

- Michael Tilly: Jaspers, Karl. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 2, Bautz, Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-032-8 , Sp. 1567-1578.

- Bernd Weidmann (Hrsg.): Existence in communication. On the philosophical ethics of Karl Jaspers. Verlag, Heidelberg 2005, ISBN 3-8260-2932-1 .

- Osborne P. Wiggins / Michael Alan Schwartz: Karl Jaspers ( RTF ; 81 kB), in: Lester Embree u. a. (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Phenomenology . Kluwer, Dordrecht and Boston 1997, ISBN ... ( Contributions to Phenomenology ), pages 371-376.

- Richard Wisser: Jaspers, Karl. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 10, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1974, ISBN 3-428-00191-5 , pp. 362-3365 ( digitized version ).

- Hamid Reza Yousefi , Werner Schüßler, Reinhard Schulz, Ulrich Diehl (eds.): Karl Jaspers. Basic concepts of his thinking. Lau, Reinbek 2011, ISBN 978-3-941400-34-4 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Karl Jaspers in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Karl Jaspers in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Karl Jaspers in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Publications by and about Karl Jaspers in the Helveticat catalog of the Swiss National Library

- Complete edition of the works of Karl Jaspers , a research project at the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences

- Levke Harders: Karl Jaspers. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Julian Schwarz, Burkhart Brückner (2015): Biography of K. Jaspers In: Biographisches Archiv der Psychiatrie (BIAPSY) .

- Jaspers' work at the Psychiatric University Clinic Heidelberg under Franz Nissl

- Peace Prize of the German Book Trade 1958 (PDF; 178 kB): Laudation by Hannah Arendt and acceptance speech by Karl Jaspers

- Richard Wisser : On the correspondence between Martin Heidegger and Karl Jaspers (PDF; 99 kB)

- Rolf Hochhuth : You have to take the plunge! - Rolf Hochhuth on Karl Jaspers as a political writer and classic: timeless warning calls and timeless significance (excerpts from a speech on the occasion of his 125th birthday in 2008)

- Annette Hilt: Topicality of the philosophy of Karl Jaspers (colloquium on the occasion of the award of the Karl Jaspers Prize 2008 to Jean-Luc Marion )

- Eckart Löhr: Review of “Karl Jaspers. Philosophy and Psychopathology "(2007)

- Video: Karl Jaspers speaks about the meaning and mission of philosophical knowledge, Basel 1959 . Institute for Scientific Film (IWF) 1960, made available by the Technical Information Library (TIB), doi : 10.3203 / IWF / G-55 .

Web links to Karl Jaspers societies

- Karl Jaspers Society Oldenburg

- Austrian Karl Jaspers Society

- The Karl Jaspers Foundation Basel

- Italian Karl Jaspers Society

- Polish Karl Jaspers Society

- Croatian Karl Jaspers Society

- Karl Jaspers Society of North America

- Jaspers Society of Japan

Remarks

- ↑ Rüdiger vom Bruch : Karl Jasper. In: Wolfgang U. Eckart , Christoph Gradmann (Hrsg.): Ärztelexikon. From antiquity to the present. 2nd Edition. Springer, Heidelberg 2001, pp. 177-179.

- ↑ Karl Jaspers: What is philosophy? A reader. 2nd Edition. Piper, Munich 1978, p. 8.

- ↑ Karl Jaspers: What is philosophy? A reader. 2nd Edition. Piper, Munich, 1978, p. 12 ff.

- ↑ Dominic Kaegi & Bernd Weidmann: "My hope was that Germany would win him". Karl Jaspers, the First World War and Philosophy , in: Ingo Runde (Hrsg.): The University of Heidelberg and its professors during the First World War. Contributions to the conference in the Heidelberg University Archives on November 6th and 7th, 2014 (= Heidelberger Schriften zur Universitätsgeschichte 6) , Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2017, pp. 99–121, ISBN 978-3-8253-6695-7 .

- ↑ Karl Jaspers: A self-portrait. Instead of a foreword. In: ders: What is philosophy? .

- ↑ a b c d e Wolfgang U. Eckart, Volker Sellin, Eike Wolgast, The University of Heidelberg under National Socialism , Springer-Verlag 2006, p. 337

- ↑ a b Hartmut Tietjen: Martin Heidegger's analysis of National Socialist university policy and the idea of science (1933–1938). In: István Fehér (Ed.): Ways and wrong ways of dealing with Heidegger's work more recently. A German-Hungarian symposium. Philosophical Writings Volume 4, Berlin / Budapest 1991, p. 122.

- ↑ a b Daniel Morat: From action to serenity. Conservative thinking with Martin Heidegger, Ernst Jünger and Friedrich Georg Jünger 1920–1960. 2007, p. 364.

- ↑ Christoph Jamme, Karsten Harries, Martin Heidegger: Art, Politics, Technology, W. Fink 1992, p. 20

- ^ Elisabeth Young-Bruehl: Hannah Arendt. Life, work and time. Frankfurt am Main 1986, p. 131

- ↑ a b Marion Heinz, Goran Gretić, Philosophy and Zeitgeist in National Socialism , Königshausen & Neumann 2006, p. 205.

- ↑ Kurt Salamun, Karl Jaspers , Königshausen & Neumann 2006, p. 18

- ↑ a b Marion Heinz, Goran Gretić, Philosophy and Zeitgeist in National Socialism , Königshausen & Neumann 2006, p. 203.

- ↑ Wolfgang U. Eckart, Volker Sellin, Eike Wolgast, The University of Heidelberg under National Socialism , Springer-Verlag 2006, p. 339

- ^ KH Bauer (ed.): About the new spirit of the university. Documents, speeches and lectures 1945/46. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg 1947, p. 1 f. (therein pp. 113–132 Karl Jaspers: From the living spirit of the university. ); Renato de Rosa: The new beginning of the university 1945. Karl Heinrich Bauer and Karl Jaspers. In: Wilhelm Dörr u. a. (Ed.): Semper apertus. Six hundred years of Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg 1386–1986. Vol. 1-6. Springer, Heidelberg a. a. 1985, here Vol. 3, pp. 544-568.

- ^ Martin Heidegger to Karl Jaspers on March 7, 1950, in: Martin Heidegger, Karl Jaspers, Walter Biemel, Hans Saner: Correspondence 1920–1963. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1990, p. 196.

- ↑ Karl Jaspers to Martin Heidegger on February 6, 1949, in: Martin Heidegger, Karl Jaspers, Walter Biemel, Hans Saner: Briefwechsel 1920–1963. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1990, p. 170.

- ^ Exhibition presentation Karl Jaspers: The book Hannah. ( Memento from January 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) In: Marbach Literature Archive .

- ↑ Karl Jaspers: Hope and Worry. Writings on German politics. 1945-1965. Piper, Munich 1965, p. 32.

- ^ Karl Jaspers: People and University. In: The change. 2, 1947, pp. 54-64. here: p. 61.

- ↑ 1958 Karl Jaspers. ( Memento from January 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) In: Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandelns (web presence).

- ↑ Karl Jaspers: About my philosophy. In: ders .: Karl Jaspers. Accountability and outlook, speeches and essays. Piper, Munich 1951, pp. 26-49.

- ^ Helmut Fuhrmann: Karl Jaspers' Goethe reception and the polemics of Ernst-Robert Curtius. In: ders .: Six studies on Goethe's reception. Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg 2002, pp. 83–122.

- ^ Robert Kurt Mandelkov: Goethe in Germany. Reception story of a classic. Volume 2, Munich 1989, pp. 140-141.

- ↑ Karl Jaspers: About my philosophy. In: ders .: Accountability and Outlook, speeches and essays. Piper, Munich 1951, pp. 333–365, here: p. 339.

- ^ Helmut Fuhrmann: Karl Jaspers' Goethe reception and the polemics of Ernst-Robert Curtius. In: ders .: Six studies on Goethe's reception. Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg 2002, pp. 83–122, here: p. 93.

- ↑ See Harmel, Pierre et al. a. (Ed.). Homage to Karl Jaspers: Prix littéraire international de la Paix, 1965 . Prix littéraire international de la Paix, Dixième anniversaire. Liège / Lüttich, October 1965. Bressoux: Stein & Roubaix, 1967. (64 pages)

- ↑ Honorary Citizen of the City of Oldenburg: Karl Jaspers ( Memento from October 23, 2017 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Website of the Karl Jaspers Clinic

- ^ City of Oldenburg: Karl Jaspers Medal ( Memento from October 22, 2017 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Nomination Database

- ↑ Karl Jaspers: Psychopathology. Springer, Berlin 1913, p. 250.

- ↑ C. Kupke: What is so incomprehensible about delusion? Philosophical-critical presentation of Jaspers' incomprehensibility theorem. In: Journal for Philosophy & Psychiatry. Vol. 1, 2008, No. 1 (online) ; Wolfgang Eirund: The limits of delusional knowledge. In: International journal for philosophy and psychosomatics. Vol. 1, 2009, No. 1 (PDF; 334 kB) .

- ↑ Huub Engels: Emil Kraepelin's dream language: explain and understand. In: Dietrich von Engelhardt, Horst-Jürgen Gerigk (ed.): Karl Jaspers at the intersection of contemporary history, psychopathology, literature and film. Mattes, Heidelberg 2009, pp. 331-343.

- ↑ Elaborated e.g. B. von Wiggins / Schwartz, also for Jaspers' psychopathology; partly contrary to Chris Walker, who judged the influence of Kant higher against the established research consensus, but also showed many influences of Husserl: Karl Jaspers and Edmund Husserl , in four parts in: Philosophy, Psychiatry, and Psychology 1994-1995.

- ↑ See e.g. B. The great philosophers. Vol. 1. 6. Edition 1997, p. 606: "In Kant, there is hardly any talk of love, and if so, then it is inappropriate ...".

- ↑ Golo Mann : Karl Jaspers. The spiritual situation of the time , commentary in: Die Zeit from June 10, 1983 (accessed on August 13, 2015)

- ↑ Karl Jaspers: My way to philosophy. In: ders .: Truth and Probation [1951]. Piper, Munich 1983, pp. 7-15 (online) ( Memento from September 13, 2012 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Reiner Wiehl : Karl Jaspers' Philosophy of Existence as Ethics, in: Bernd Weidmann (Ed.): Existence in Communication: on the philosophical ethics of Karl Jaspers, Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg 2004, pp. 21–34.

- ↑ Kurt Salamun: Karl Jaspers. 2nd Edition. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2006, p. 52.

- ↑ Karl Jaspers: Introduction to Philosophy. Twelve radio lectures. Zurich 1950, p. 17.

- ↑ Klaus Piper reports that the total circulation was already more than 900,000 copies in 1963, in: Encounter of the publisher with Karl Jaspers. Piper, Munich 1963, based on: Kurt Salamun: Karl Jaspers. 2nd Edition. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2006, p. 127.

- ↑ Cf. Wätjen, Hans-Joachim: ">> He read with a pencil ... <<: Karl Jaspers' library as a source for research", in: Offener Horizont: Jahrbuch der Karl Jaspers-Gesellschaft [Oldenburg] , Vol. 1 (2014), ed. v. Matthias Bormuth, pp. 59-71.

- ↑ Kurt Salamun: Karl Jaspers. 2nd Edition. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2006, p. 127.

- ^ Jeanne Hersch: Jaspers in France. In: Klaus Piper: Meeting of the publisher with Karl Jaspers. Piper, Munich 1963, p. 150, based on: Kurt Salamun: Karl Jaspers. 2nd Edition. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2006, p. 127.

- ^ Otto Friedrich Bollnow: Existential philosophy and pedagogy. Stuttgart 1959.

- ^ Helmut Fahrenbach: Communicative Reason - a central point of reference between Karl Jaspers and Jürgen Habermas. In: Kurt Salamun (ed.): Karl Jaspers. To the topicality of his thinking. Munich, Piper 1991, pp. 110-127.