Konrad II. (HRR)

Konrad II ( Konrad the Elder ; * around 990; † June 4, 1039 in Utrecht ) was Roman-German Emperor from 1027 to 1039, from 1024 King of Eastern Franconia (regnum francorum orientalium) , from 1026 King of Italy and from 1033 King of Burgundy .

Konrad succeeded his childless predecessor, the Ottonen Heinrich II , and became the founder of the new royal family of the Salians . In church politics, Italian politics and in interpreting the idea of the emperor, he continued seamlessly with the achievements of his predecessor. Konrad further expanded the position of the empire. Like Heinrich, he relied on the imperial church . Like him, he also avoided interfering with the situation in Rome. His reign marks a high point of medieval imperial rule and a relatively calm phase of the empire. He completed the acquisition of the Kingdom of Burgundy initiated by Heinrich. With the successful incorporation of Burgundy into the imperial union , the idea of the "triad" of empires (tria regna) arose , that is, the amalgamation of the East Franconian-German, Italian and Burgundian kingdoms under the government of the German king and Roman emperor. Konrad's reign was accompanied by a process of “transpersonalization” of the community, which led to a mental separation between king and empire. Under his rule, the rise of Speyer began as a place of memory and rulers' burial place .

Life until the assumption of power

Origin and family

Konrad belonged to a family that was only occasionally referred to as Salic in the 12th century and increasingly since the 14th century. His ancestors are likely to be found in the Widonen clan , a family that was part of the ruling class of the empire as early as the 7th century. At the end of the 8th century, the Widonen clan split into different branches. A part established its rule in Worms and Speyergau . Since the beginning of the 10th century, starting with a Werner who was count in Worms-, Nahe- and Speyergau, the line of Salian ancestors can be traced on without interruption. The rise of the family began with Konrad the Red . He expanded his father's property and in 941 belonged to the closest retinue of King Otto the Great . In 944 (or 945) he was made duchy of Lorraine. By marrying Otto's daughter Liutgard in 947, he consolidated his closeness to the king. But Konrad felt snubbed when the king rejected an agreement he had brokered with Berengar II , Otto's not yet defeated rival for the Italian royal crown. In addition, he saw his influence at the royal court threatened by the growing influence of Otto's brother Heinrich . In 953 he therefore joined the Liudolfin uprising , which was suppressed. Konrad was stripped of the Duchy of Lorraine . In 955 he was killed in the battle against the Hungarians on the Lechfeld .

The family began to rise again after Konrad's death. His son Otto von Worms , a grandson of Otto the Great, was named Count in Nahegau in a royal charter in 956. He also owned the counties in Mayenfeld, Kraich , Elsenz , Pfinz and Enzgau and perhaps also in the Uffgau . After the failure of an uprising by southern German princes, Emperor Otto II conferred on him the ducal dignity of Carinthia in 978. However, this was accompanied by the loss of sovereign rights on the Middle Rhine and in Worms; they were awarded to the local bishop Hildebald . After another reorganization of the southern German duchies, Otto von Worms was able to return in 985 and take up the fight with Hildebald von Worms for the city. For his renunciation of the ducal dignity of Carinthia, the guardianship government of Otto III entrusted him . the Lautern royal court (Kaiserslautern) and the Wasgau forest, which was extremely important for further expansion of the rule. Otto carried on the title duke (dux) even without a duchy. His renunciation of Carinthia had not diminished his rank; his domain with the center of Worms can be understood as an increased rule by the nobility and grand counts. As early as 995, however, Otto was reassigned the Duchy of Carinthia. The proximity of the family to the king led under Emperor Otto III. also in 996 for the elevation of Brun, a son of Otto von Worms, to Pope Gregory V.

The marriage of Heinrich , Otto von Worms' eldest son, to Adelheid probably took place at the time when Otto was a duke without a duchy. From Heinrich's marriage to Adelheid, Konrad the Elder emerged, who later became Konrad II. Konrad's father died at a young age. Konrad's mother came from a noble family in Upper Lorraine. Soon after Heinrich's death she married a Frankish nobleman. After her remarriage, Adelheid hardly paid any attention to Konrad. Although the Salier left relics to his mother for the Canons' Monastery of Öhringen , no other close ties can be proven. Konrad's mother never appears as an advocate, and no source reports her presence at court. Around 1000 Konrad was given to Burchard, Bishop of Worms, for education. According to Sal-Franconian law, he should have come of age at the age of twelve.

After the death of Otto III. Konrad's grandfather Otto von Worms was one of the candidates for the king's election, but could not prevail against Heinrich II. As a result of the change of the throne in 1002, the Salians lost their political influence and were finally expelled from Worms. Otto von Worms renounced the family's possessions in this region as well as Worms Castle. As a replacement he received the important royal court Bruchsal with extensive possessions and the royal forest Lußhardt from the king . Due to the early death of Salier Heinrich, his younger brother Konrad and not Heinrich's son Konrad (the elder) took over the Salic inheritance in 1004. The division of his grandfather's inheritance reduced opportunities for social advancement. After the early death of his uncle, Duke Konrad of Carinthia, in 1011, Konrad the Elder took over the care of his little son, Konrad the Younger. The Duchy of Carinthia, however, was withdrawn from Konrad the Younger. Heinrich II transferred it to Adalbero von Eppenstein .

Marriage to Gisela von Schwaben

Konrad married Gisela von Schwaben, who was about the same age and widowed twice, in 1016 . Gisela was the daughter of Hermann von Swabia , who had unsuccessfully asserted his own claims when the king was elected in 1002. She was married to the Saxon Count Bruno von Braunschweig and then to Ernst from Babenberg . In 1012 Ernst received the Duchy of Swabia. The sons Ernst and Hermann came from the marriage . After the death of the father, Heinrich II transferred the duchy to the older son Ernst. As a future husband, Konrad could hope to be able to take over the administration of the duchy during the minority of the stepson and thus to emphasize his ducal rank in addition to a significant increase in power and to make a claim to a duchy that became free. But Heinrich II tried to prevent Conradin-Salian influence and after his marriage to Konrad excluded Gisela from the administration of the Duchy of Swabia and transferred the guardianship of her son Ernst II and thus also the management of the duchy to the brother of the late Duke Poppo , who also became Archbishop of Trier in 1016. The relationship between the emperor and the Salians therefore remained tense. On August 27, 1017, Konrad is proven to be an ally of Count Gerhard, a vehement opponent of Heinrich II.

Despite the failed hope in the Swabian duchy, the marriage with Gisela was advantageous, because she brought rich personal property and a glamorous origin into the marriage. Her mother Gerberga was a daughter of King Konrad of Burgundy and a granddaughter of the West Franconian Carolingian ruler Ludwig IV. Her father Hermann II was also a direct descendant of the Carolingians. Gisela's line of ancestors thus went back to the ruler Charlemagne . Both spouses had a common ancestor in Liudolfinger Heinrich I. Konrad in the fifth generation, Gisela (through her mother Geberga) in the fourth generation. So the two were related to each other over nine degrees. Although under canon law only marriages up to the seventh degree were forbidden, some contemporaries - including Thietmar von Merseburg - rejected this connection as an illegal marriage of relatives . In the first year of their marriage, their son Heinrich, the fourth and last son of Gisela, was born on October 28, 1017. This son was named Heinrich III. the successor of his father as ruler of the empire.

King elevation

After Heinrich's death, the period without a king lasted only a few weeks. During the time of the vacancy of the throne, Heinrich's widow Kunigunde ran the imperial business, supported by her brothers, Dietrich II and the Bavarian Duke Heinrich V , but certainly also by Aribo von Mainz . It also kept the imperial regalia in its power in order to hand them over to the elected and thereby empower him to rule. In the eight weeks of the vacancy of the throne, intensive preliminary negotiations between the big players took place in small groups. According to Steffen Patzold's thesis, Bishop Egilbert von Freising created the Codex Monacensis Latinus 6388, a small, annotated catalog of rulers from Clovis I to Heinrich II. The catalog gave Egilbert an overview of changes of throne, division of the empire and childless ruler's deaths. The compilation of information had a pragmatic function. It was geared towards the debates and negotiations leading up to the open succession to the throne.

On September 4th, the princes gathered in Kamba , a now submerged place on the right bank of the Rhine opposite Oppenheim . Aribo von Mainz acted as election supervisor. In Kamba, only the two cousins of the same name, Konrad, called the elder, and his younger cousin Konrad were considered candidates for kingship. Both were related equally to the extinct Liudolfinger dynasty. Their grandfather, Duke Otto of Carinthia, was a grandson of Otto the Great through his mother Liudgard, the wife of Duke Conrad the Red . In 1024 there were still more relatives of the Ottonian house, but they were out of the question as candidates. A designation by Heinrich II, as the later tradition almost unanimously asserts, should not have existed.

Wipo , who was probably present at the election meeting in Kamba, left an idealizing picture of the election of the first Salic king. He stylizes the processes into a free, ideal choice. Therefore Wipo allows the Saxons and other eligible voters to participate, but they were not represented at all or at least not represented by their leading representatives. The Saxons had discussed the election of a king at a princes' day in Werla and adopted a wait-and-see attitude. The Lorraine people were in opposition and evidently spoke out in favor of the other, the younger Konrad. But a majority should have preferred Konrad the elder. The motives of those in favor of his kingship are unclear. Possibly it was the missing descendants of Konrad the Younger who felt the majority of voters as a lack. Konrad the Elder already had a seven-year-old son in 1024, which meant that a new ruling dynasty could be established permanently. The argument of idoneity, the ability to exercise power successfully, must have played a decisive role in the choice of Conrad the Elder. According to Wipo, it was Konrad's virtus or probitas (efficiency and righteousness) character traits that were the reason for the broad approval. But only after a long speech between the two opponents could the two cousins come to an agreement. In this speech faked by Wipo, Konrad the Elder was able to convince his cousin to accept the election result regardless of the success of his own candidacy. What other promises he made to him is unknown. As compensation for his renunciation, he could have been promised a freed duchy or even participation in rulership.

The Archbishop of Mainz Aribo acted as election officer and was the first to vote for Konrad. The other clergymen followed him according to their rank. Then the worldly greats followed. The Cologne Archbishop Pilgrim and the Lothringers could not be won over for Konrad the Elder and left the place. The imperial widow Kunigunde presented Konrad with the imperial insignia - crown, scepter , imperial orb and other treasures that symbolized royal rule - and thus placed the new ruler in the tradition of his predecessors.

king

Coronation of Konrad in Mainz and delay of Gisela's coronation

The coronation of the new king took place on September 8, 1024, on the high feast day of the birth of Mary . Using the example of the succession to the throne of Konrad II, Gerd Althoff and other historians have worked out the importance of productions. On the procession for the consecration in the Mainz Cathedral , Konrad was publicly required to demonstrate his ability to clementia (mildness), misericordia (mercy) and iustitia (justice): he forgave a previous opponent, he had mercy on a poor man, he left a widow and to do justice to an orphan. These were innovations in the ceremonial of the ascension of the king. The ruler was committed to his obligations as a Christian ruler when he took office. There may be a connection to its predecessor, who lacked rulership virtues such as justice and mercy. In the Mainz Cathedral, Konrad was anointed by Aribo and crowned king . Which crown was placed on the anointed head of the new ruler in 1024 remains unknown. According to current opinion, the so-called imperial crown was made around 960 at the earliest for Otto I and at the latest for Konrad II. According to other considerations, the crown was not created until the middle of the 12th century for the first Hohenstaufen king, Konrad III. The process of the transpersonalization of rule could have found its most tangible expression in a changed understanding of the imperial insignia. It is possible that Konrad II first developed the idea of the "emperor who never dies" in this context.

In Kamba, Aribo had not only pushed through his candidate, but also the leadership of the election and his first voting right, and had finally reached the climax of his validity with the coronation ceremony in Mainz. In the struggle for the top position in the episcopate, the Metropolitan of Mainz had prevailed against the Archbishop of Cologne, Pilgrim. Soon after taking office, Konrad made him the Italian Arch Chancellery . Aribo was henceforth arch chaplain and thus nominal head of the German chancellery and at the same time the highest head of the Italian document authority. But Aribo refused to crown Gisela in Mainz. Wipo does not give an exact reason for the offensive behavior - a scandal, the causes of which are still puzzling to research today. None of the speculations can be proven by the sources. Aribo's refusal had significant consequences for the Mainz coronation law. Pilgrim recognized his chance to win the coronation right for Cologne in the long run and crowned Gisela queen on September 21, 1024 in his cathedral. The political reorientation of Pilgrim also weakened the opposition of the new king.

Assumption of power and king ride

The monarchy presented Konrad with numerous problems. In order to secure his rule across the empire, the Saxons and Lorrainers who remained in the opposition had to be won over. Even with his cousin of the same name, there was still no permanent settlement. Before Konrad went on his royal ride , Bruno von Augsburg and Werner von Straßburg received court offices. With the subsequent month-long king ride through large parts of the empire, Konrad tried to get a general confirmation of his choice. The tour began with the train from Cologne to Aachen , where the ruling couple arrived in Cologne two days after Gisela's coronation. There Konrad took his place on the throne of Charlemagne and consciously placed himself in the Carolingian tradition. Ever since Otto the Great, ascending and taking possession of the throne, the “ore chair of the empire”, was an indispensable part of taking over power in the empire. He held a court day in Aachen. But Konrad did not succeed in winning over the Lorraine opposition even at this traditional site. Then his way led him via Liège and Nijmegen to Vreden , where the ruling couple were warmly welcomed by Adelheid von Quedlinburg and her sister Sophie von Gandersheim . Since both sisters were daughters of Otto II and thus representatives of the old ruling dynasty, this should have had an impact on the further attitude of the Saxon nobility towards Konrad as king. In the first half of December, the Westphalian bishops and grandees met with Konrad and paid homage to him. Extensive negotiations were probably held in Dortmund , which served to prepare for the magnificently staged court day at Christmas in Minden . Konrad celebrated Christmas there. The archbishops Aribo of Mainz, Pilgrim of Cologne , Hunfried of Magdeburg and Unwan of Hamburg-Bremen, the bishops Bruno of Augsburg, Wigger of Verden and the landlord Sigibert von Minden as well as numerous Saxon greats under the leadership of Duke Bernhard II were attested as present . After Konrad had promised them that he would respect the old Saxon law, he was recognized as king by the greats. This act of authority meant the recognition of Salian kingship. Bernhard II and Konrad respected each other in the period that followed. Konrad's rule remained the only one in the 11th century in which no stronger opposition from the Saxon nobility or even an uprising can be proven.

The royal couple stayed in Saxony for more than three months and moved through Paderborn , Corvey , Hildesheim , Goslar and above all Magdeburg . In March 1025 the couple left Saxony and moved to Swabia via Fulda . In Augsburg it celebrated Easter on April 18th. There a conflict broke out with his cousin, Konrad the Younger. The reasons have not been passed down, but the younger Salier apparently demanded compensation for the renunciation of Kamba, participation in the Burgundian rule and the Kingdom of Burgundy or the granting of the Duchy of Carinthia . But Konrad rejected his cousin. From Augsburg it went to Regensburg. Konrad held a court day there at the beginning of May 1025 and presented his royalty at this central Bavarian town. The Regensburg nunneries of Obermünster and Niedermünster were granted privileges. Then Konrad moved on via Bamberg , Würzburg and Tribur to Constance . There he celebrated Pentecost on June 6, 1025. Konstanz also brought Konrad into contact with Italian rulers for the first time.

Troubled conditions in Italy

The great Italians and the important Archbishop Aribert of Milan came to Constance to recognize the new king. But the situation in Italy remained unstable after the death of the last Liudolfinger ruler, Heinrich II. A group of Italian greats offered the King Robert II of Capetan and his eldest son Hugo the Lombard kingship. After its rejection, the same group probably turned to Duke Wilhelm V of Aquitaine . But Wilhelm strove for his son's candidacy on the condition that all spiritual and secular greats campaign for it. However, in the summer of 1025 in Italy, Wilhelm became aware of the hopelessness of his son's candidacy, so he renounced it.

In addition to the great Italians, envoys from Pavia also appeared in Constance . After the news of the death of Henry II , the Pavese had destroyed the Palatinate, which had still come from Theodoric the Great , down to its foundation walls. Although Pavia had lost its traditional importance as the seat of royal administration under the Ottonians, it still had a certain symbolic value. They tried to justify their actions before the new king. The episode handed down by Wipo in this context reveals the conception of the “permanence” of kingship (transpersonal rule), of a kingship that continues independently of the person of the respective king as an institution and “legal person”. In their conversation with Konrad, the Pavese invoked the usual notion of the personal character of rule. They tried to justify themselves by saying that after the death of Emperor Heinrich there was no king and that no one was harmed. Konrad did not allow these excuses and answered them with the now famous ship metaphor: "If the king is dead, the kingdom remains, just like a ship whose helmsman has fallen." According to this view, the imperial property belonging to the kingship was retained without a king its legal character. Therefore, the Pavese destroyed royal and not private buildings and made themselves a criminal offense. The conflict could not be resolved. Pavia persisted in opposition to Salian rule. The destroyed Palatinate was never rebuilt. Konrad left the southern Alpine affairs to himself for the time being and continued his royal ride.

Claim to the Burgundian succession

From Constance it went via Zurich, where Italian greats paid homage to him, in the second half of June 1025 to Basel. Konrad held a court day around June 23rd. Uldarich was made bishop in Basel. Konrad's predecessor Heinrich II had Basel in 1007 from Rudolf III. acquired as bargaining chip for the future attack of the entire Kingdom of Burgundy. But the death of childless Heinrich made the question of inheritance appear open again. The court day and the bishop's investiture make clear Konrad's claim to want to step directly into the rights of his predecessor. After Wipo, the king's ride (iter regis per regna) of Konrad II ended in Basel . In the previous ten months the Salier had crossed all the important regions of the empire with Lorraine, Saxony, Swabia, Bavaria and Franconia. But after the election of Kamba , Duke Gozelo of Lower Lorraine had sworn bishops and secular greats, such as Duke Friedrich II of Upper Lorraine, not to pay homage to Konrad without his consent.

Little is known about Konrad's activity during the summer and autumn months of 1025. During this time the various opposition groups against Konrad came together. Among them were the Dukes Ernst of Swabia, Friedrich of Upper Lorraine , Konrad the Younger and the Swabian Count Welf II. Meanwhile, Konrad moved from Basel via Strasbourg and Speyer to Tribur , where he held a court day. Perhaps the first preparations for an Italian train have already been made in Tribur. It was not until Christmas 1025 in Aachen that Gozelo, Friedrich and the Bishop of Cambrai Gerhard paid homage to the new ruler and were the last to recognize Konrad's kingship.

Gandersheim dispute

During his ride to the king, Konrad first tried to intervene in the Gandersheim dispute . This dispute over the question of whether Gandersheim belongs to the Hildesheim or Mainz diocese went back almost 40 years. Archbishop Aribo of Mainz sued Bishop Godehard of Hildesheim to place the Gandersheim monastery under the spiritual jurisdiction of the Mainz church. Konrad had been indebted to the archbishop since his election, but from the reign of his predecessor there was a resolution in favor of Hildesheim that had existed for almost twenty years. Konrad therefore postponed the decision to a court court day that was to take place in Goslar at the end of January . In Goslar, however, no decision was made, rather both parties were prohibited from exercising jurisdiction in the disputed area. A synod in Frankfurt on September 23 and 24, 1027 , could not end the dispute either. A synod at Pöhlde on September 29, 1028 did not provide a solution either. The dispute was only resolved on Merseburg Whitsun Day in 1030. In personal negotiations with Bishop Godehard von Hildesheim, Aribo renounced the monastery.

First train to Italy

From Aachen Konrad moved to Augsburg via Trier. An army assembled there in February 1026 for the Italian campaign. In the wake of Konrad were the archbishops Aribo of Mainz and Pilgrim of Cologne. The army is believed to have comprised several thousand armored riders. He could not defeat Pavia militarily. Konrad probably left some soldiers behind, who caused damage in the Paveser area and thus blocked all trade and shipping. There is evidence that Conrad was in Milan on March 23, 1026. The end of March, he was probably of Aribert for King of the Lombards crowned. Konrad moved from Milan to Vercelli , where he celebrated Easter on April 10th with his faithful Leo von Vercelli . With Leo's death a few days later, Aribert became the head of the Salier-friendly party. With the help of Konrad, he intended to expand the leadership position of the Lombard metropolis and the independence of the Church of St. Ambrose .

In June Konrad stayed with his army in Ravenna , where a battle broke out between the billeted foreigners and the Ravennates. Konrad withdrew to the north in order to reduce the risk to his army from the summer heat. At the beginning of autumn 1026 Konrad left his summer camp, descended into the Po Valley and traversed the Lombard lowlands from the Adige to the Burgundian border. During this time Konrad is said to have held court, pacified the empire and passed court judgments. Specific details have not been passed down. Konrad celebrated Christmas in Ivrea . In winter the margraves of northern Italy ended their opposition and took the side of the king. However, Pavia did not find a compromise with Konrad until the beginning of 1027, probably through the mediation of Abbot Odilo von Cluny .

The emperor Konrad II.

Imperial coronation

On Easter Sunday 1027, March 26th, the imperial coronation of Konrad and Gisela took place in St. Peter's Church in Rome by Pope John XIX. instead of. The coronation is one of the most glamorous of the Middle Ages. With her were Knut the Great and Rudolf III. von Burgundy, the Grand Abbot Odilo von Cluny and at least 70 high-ranking clergymen, such as the Archbishops of Cologne, Mainz, Trier, Magdeburg, Salzburg, Milan and Ravenna were present. Konrad's heir to the throne, Heinrich, had also come to Italy. Rudolf's participation meant a rapprochement between Burgundy and the Roman-German Empire. During the coronation ceremony, which lasted over seven days, a dispute arose between the archbishops of Milan and Ravenna over the ceremonial precedence in the imperial escort, which was decided in favor of Milan.

After the imperial coronation, 17 documents were issued, especially for Italian monasteries and dioceses. On April 6, the centuries-old dispute between the Patriarchates of Aquileia and Grado was decided in favor of Poppo of Aquileia in the Lateran Basilica . The whole of Veneto was subordinated to the Church of Aquileia. Grado was only left with the status of a parish , with which the patriarch was finally invested in a joint act by the emperor and the pope . Carefully implemented, this decision resulted in the destruction of the independence of the Church of Venice and at the expense of the city's political autonomy. Konrad did not even enter into negotiations with Venice. Years later he still considered them to be enemies of the Reich and rebels. With this decision Konrad broke for the first time with the policy of Henry II, who, like his predecessors, had renewed the contract with Venice. Konrad intended to secure Poppo's unconditional loyalty by doing this. Aquileia was supposed to provide imperial support in northeastern Italy. However, the decision did not last. The conditions that had existed since the 6th century were restored by a new synod judgment in 1044.

Conrad is attested in Rome until April 7th. In the following weeks he moved to southern Italy and received homage from the princes of Capua , Benevento and Salerno . But Konrad was back in Ravenna on May 1, 1027.

Imperial politics

Nobility politics

On May 31, 1027 Konrad can be traced on the territory of the Bavarian Duchy in Brixen . After his return from Italy, the Duchy of Bavaria in Regensburg became vacant due to the death of Henry V. With the appointment process, the research starts “the institutionalization of the royal right to choose”. The award of the duchy to a not yet ten-year-old, non-Bavarian king's son was unprecedented. Konrad did not affect the electoral rights of the great, but his authority was in the meantime so consolidated that he selected from a much larger group of people when awarding the ducal office and passed over candidates with far better inheritance claims. By directing the choice to his son, Konrad was able to appoint the already-designated king as duke. On June 24, 1027, he had Heinrich of the Bavarian greats elected Duke in Regensburg. An increasing abstraction of the state concept is documented by the recuperation procedure initiated by Konrad at the Regensburg Hoftag at the end of June 1027 to determine the imperial property in Bavaria. In this procedure, counts and judges had to give information about the affiliation of castles and abbeys, of which possessions "they knew that they rightly belonged to the throne of his empire, ad solium imperii ". However, an immediate success of this measure is not known. In the case of the emperor's widow Kunigunde's dispositions over her Wittum , Konrad also expressly stated that he was not bound by it (DKII. 191) and claimed her widow's property as an imperial property after her death. Changes in the relationship between kingship and ducal power were also evident in the two southern German duchies of Carinthia and Swabia.

Serious revolt of Swabia

After Konrad's ascension to power, Ernst von Schwaben joined a coniuratio (sworn unity) for reasons that were not clear . On the intervention of his mother, his stepbrother Heinrich III. and another great he was again accepted and moved to Italy with Konrad. During the Italian campaign, Konrad the Younger and Count Welf continued their resistance. Welf had got into a conflict with the regent Bruno von Augsburg . With the task of maintaining the peace, Konrad sent his stepson Ernst back from Italy to the Swabian duchy after September 15, 1026, and gave him the Kempten Abbey as a fief . It was the first feudal award of an imperial monastery to a lay prince since the Carolingian era . But Ernst rejoined the opposition. He invaded Alsace and probably began to build castles in the Burgundian region in view of the Burgundian heritage. After Konrad's return from Italy, a consultation about the Swabian uprising took place in Augsburg in the first half of July 1027. On a subsequent court day in Ulm in the second half of the month, the conspirators were asked to surrender. The Wipos report (Chapter 20) provides the following about the events there: Trusting in the number and loyalty of his vassals, Ernst presented himself in Ulm. But when Ernst reminded his vassals of the loyalty they had shown him and warned them not to abandon him, the two Counts Friedrich and Anselm, as spokesmen, replied that they swore loyalty to everyone, but not to the king. In view of the attitude of his vassals, Ernst Konrad submitted. Welf II also submitted. In addition, at the beginning of September 1027, Conrad the Younger ended his revolt and in autumn 1027 found himself ready to submit. As Duke of Swabia, Ernst was deposed and imprisoned at Giebichenstein Castle . In 1028 or 1030 he was pardoned by Konrad and reinstated in his duchy. In return he had to give up his property in the Bavarian Nordgau.

When Konrad presented his stepson on the Osterhoftag 1030 in Ingelheim with the decision to take an oath to his closest comrade in arms and most loyal vassal Werner von Kyburg and to fight him as a public peace criminal, Ernst decided in favor of the higher right of loyalty. Konrad then had Ernst put on trial for high treason " hostis publicus imperatoris " and deposed by a prince's verdict. In addition, Ernst and his people were excommunicated by the bishops. Even his mother dropped him now. Ernst then tried in vain to win Count Odo of Champagne as an ally. On August 17, 1030, Ernst and Werner were killed in a battle against their persecutors. Konrad compared his downfall to the end of a mad dog. Ernst's fall has decisively weakened the Swabian ducal power and prepared the dissolution of the duchy. Konrad's son Heinrich III. took over the Duchy of Swabia in 1038 .

Fall of Adalberos from Carinthia

The claim to royal authority could also be enforced against the Carinthian Duke Adalbero . As recently as 1027, Adalbero was Konrad's sword-bearer at the Synod of Frankfurt , which indicates a special position of trust. After 1028, Adalbero can no longer be found in royal surroundings. In the following years he ran an independent policy in the Carinthian area. Unlike the emperor, he apparently tried to work towards an arms and peace treaty with the Hungarians.

At the instigation of the emperor, he was charged around May 18, 1035 on a court day in Bamberg. Konrad demanded that the princes present pass the sentence and deprive Adalbero of the duchy and the march. However, the princes hesitated and demanded the presence of Henry III. But the heir to the throne also refused to fulfill Konrad's request because of an earlier personal agreement (pactum) he had made with Adalbero. Even exhortations, requests and threats from Konrad kept Heinrich steadfast. Konrad was only able to assert himself through the said means, the footfall in front of the son. The king's self-humiliation meant that he was ready to violate the dignity of his person for the continued existence of kingship and empire. Heinrich justified himself by swearing an oath to Adalbero at the instigation of Egilbert von Freising . Konrad did not go into Egilbert's apologies and attempts at justification and expelled him from the court. The trial was resumed and Adalbero and his sons were sentenced to exile. The duchy remained unoccupied until February 2, 1036 and was awarded to Konrad the Younger with Carinthia on a court day in Augsburg. In 1039, after Konrad's death, Heinrich also took over the Duchy of Carinthia. The three southern German duchies were thus under the control of the king. The development of the centralization of the ducal and rulership rights in the empire in the hands of the king, which began under Heinrich II. , Took place under Conrad II and his son Heinrich III. another increase. The duchies took on the role of substitute royalty.

The rituals of conflict management handed down from the Ottonian period , according to which complete submission had to be followed by rehabilitation through regaining patronage, lost much of their importance with Heinrich II and Konrad II. Konrad tried to manage the conflict through the formal use of the high treason process, which legitimized the intervention against rebels such as Ernst von Schwaben or Adalbero von Kärnten as "enemies of the state". The ruler's expanded scope shifted the distribution of power in his favor, so that it was understood as cruelty and a breach of tradition.

Church politics

Konrad's predecessor had exercised an energetic royal rule over the imperial church . The imperial churches were used more than ever for servitium regis (royal service), for hosting and accommodating the royal court. Konrad continued this. Konrad demanded the obligation to provide accommodation and hospitality and the provision of military personnel just as energetically as his predecessor.

In his Gesta Chuonradi , Wipo assigns little importance to the church and its support by the king. Konrad II and his family showed little interest in founding new monasteries. In particular, Konrad's strengthening of imperial rights was at the expense of an independent monastery policy. With only one foundation, the conversion of the canons of Limburg an der Haardt into a monastery in 1025, the Salians were far less active than the Ottonians, who founded eight monasteries or at least played a decisive role in their foundation. Heinrich's first wife Gunhild was buried in Limburg . But the founding of the Limburg monastery was probably not intended as a location for the establishment of a representative family burial place of the Salian family. Limburg is to be understood as a temporary solution, as Speyer was still a construction site at that time. Konrad could have reserved the burial in Speyer as a donor's burial place. With the birth of Beatrix Gunhild had a daughter, but no heir to the throne and could no longer work to preserve the dynasty. She was excluded from the inner circle of the royal dynasty with regard to her burial place.

With five synods with his participation, Konrad's synodal activity also lagged far behind that of his predecessor. The synodal instrument was only of importance to Konrad when the general peace was disturbed. Gisela was able to repeatedly exercise her influence in Konrad's church policy decisions. After the death of Archbishop Aribo of Mainz in 1031, the cathedral scholaster and dean Wazo of Liège was the candidate of Conrad. But on Gisela's intervention, the less important Bardo was made archbishop. At the royal court, Bardo lost all influence as Archbishop of Mainz.

Similar to his predecessor Heinrich, but in far fewer places, Konrad fraternized with cathedral chapters . On April 30, 1029, Konrad issued a diploma for the Regensburg women's monastery in Obermünster , in which Konrad confirmed and restituted a donation from Heinrich II to the monastery. Konrad, Gisela and Heinrich were then included in Obermünster's memory of the dead . Before February 26, 1026 at the latest, Konrad became a brother of the Worms canons. Konrad had special personal relationships with Eichstätt. After Heribert's death, Konrad raised the Eichstätter cathedral canon Gebhard to the position of Archbishop of Ravenna. Together with his wife he was accepted into the prayer fraternity. Konrad praised Gebhard in the certificate conferring the County of Faenza to Ravenna as one of his most loyal followers (DKII. 208, 1034).

Relationship to the East

Poland

Boleslaw had shaped Poland into a great power. Shortly after the death of Henry II, he was crowned king “in disregard for Konrad” ( in iniuriam regis Chuonradi ), probably at Easter 1025. Boleslaw died on June 17, 1025, but his successor Mieszko II was crowned king, along with his wife Richeza . He drove his brother Bezprym , who leaned on Konrad, into exile. The two Polish uprisings were viewed by Konrad as hostile acts and disregard of his sovereign rights. His first reaction should be the establishment of relations with King Canute of Denmark and England. In 1028 Mieszko invaded the eastern Marche of Saxony. The reason for the incursion is uncertain. Possibly it was related to the rapprochement between Konrad and Knut II of Denmark , which Mieszko feared unfavorable effects for his country. The enemy devastation led to the relocation of the Zeitz diocese to Naumburg at the end of 1028 . However, the upgrading of the Meissen memoria is likely to have been an important motivation, since a bishop's church was able to preserve the burial place of Ekkehard I more permanently. After eventful campaigns in 1031 Konrad was able to force the return of the Lausitz and Milzener Land, which had once been won by Boleslaw . In July 1033 Mieszko found himself ready to make peace at the emperor's court day in Merseburg , renounced the royal dignity, accepted the vassal relationship to the emperor and empire and recognized the return of the Lausitz and the Milzener Land. Poland was divided into three domains. Mieszko received supremacy, but died on May 10 or 11, 1034.

Bohemia

The Bohemian Duke Udalrich refused the attendance required for the imperial grace at the Merseburg court conference in July 1033 , whereupon the Bohemian was exiled as a majesty criminal (reus maiestatis) . According to another version, Břetislav seized the rule in place of the deposed Udalrich without obtaining the imperial approval. At the age of 17, Konrad's son Heinrich III took over. his first independent command. The military enterprise ended in success and the duke's submission. In late autumn Konrad awarded the duchy to Udalrich's brother Jaromir . But already in 1034 Udalrich got half of the duchy back and had to share the rule with Břetislav. Udalrich died in 1034. Previously he had blinded his brother Jaromir, the blind duke then renounced the rule. The new Duke Břetislav recognized the suzerainty of the emperor, paid homage to Salier in Bamberg in May 1035 and held hostages.

Hungary

In 1030 a conflict broke out with Hungary. The background is unclear. Border disputes between Bavaria and Hungary probably led to a military action by Konrad, which, however, failed completely. After the argument with his stepson Ernst, Konrad left the Hungarian affairs to his son Heinrich. The conflict was probably settled in 1031. Heinrich left the stretch of land between Leitha and Fischa to the Hungarian king . It was not until the reign of Henry III. should the conflicts with Hungary break out again.

Acquisition of the Kingdom of Burgundy

King Rudolf III , who had no sons, bequeathed his kingdom to his closest relative Heinrich II, the son of his sister Gisela . When Heinrich died before his uncle, however, according to inheritance law, the Burgundian inheritance would also have lapsed, because Conrad II had no rights to Burgundy. However, according to his transpersonal idea of rulership, Konrad claimed the same rights as his official and legal predecessor Heinrich II. From a purely inheritance point of view, Count Odo II of Champagne, as Rudolf's nephew, was more closely related to the Burgundian king than any other possible pretender. Odo became the Saliers' only serious rival for the acquisition of Burgundy.

As early as August 1027, Konrad met Rudolf near Basel to arrange the transition to Burgundy with him. Queen Gisela mediated the decisive peace bond between the two. In addition, it was possible to achieve that "the Kingdom of Burgundy was transferred to the emperor under the same conditions (eodem pacto) under which it had previously been awarded to his predecessor, Emperor Heinrich." When King Rudolf III. died on September 6, 1032, Konrad was currently on a campaign against Poland. Conrad immediately broke off the campaign and hurried with his troops to Burgundy in the winter of 1032/33. But by the end of the year Odo advanced into Burgundy and took possession of large parts of the kingdom, especially in the west. In the second half of January 1033 Konrad appeared in Burgundy and moved to Peterlingen (Payerne) via Basel and Solothurn . On February 2, he was elected and crowned King of Burgundy by his supporters. But the conquest of Neuchâtel and Murten failed . Because of the extraordinarily severe winter, Konrad had to retreat to Zurich. There, too, he was recognized as king in front of another group of Burgundian nobles. But only two large-scale military campaigns by Konrad in the summer of 1033 and 1034 brought the decision. On August 1, 1034, the acquisition of Burgundy was brought to a conclusion in the cathedral of Geneva in a demonstrative act .

As the future domain of the emperors, Burgundy was only a sideline. The limited power of the Rudolfinger was not expanded by the Salians. Rather, Konrad hardly intervened there after his elevation to the rank of King of Burgundy. Only one document has survived for Burgundian recipients, which he had issued on March 31, 1038 in Spello in Spello . The associated enlargement of the ruling zone of influence and the upgrading of the imperial dignity are assumed to be the main motive of Konrad for the acquisition of Burgundy. However, Konrad now also ruled the Western Alpine passes, which enabled him to secure rule in Italy.

Founding of a dynasty and securing the succession

Rise and promotion of Speyer

Speyer was probably a rather poor diocese around the turn of the millennium. Neither among Carolingians nor Ottonians had it played a special role. The Salian sphere of influence on the Rhine enclosed and touched the high churches of Mainz, Worms and Speyer. For Konrad, however, there was no alternative to Speyer. Mainz was firmly in the hands of the archbishop, and in Worms the local bishop tried to push back Salian influence. One reason for the sponsorship of Speyer could not least be the memorial maintenance of the ancestors and descendants. The bloody deed of his count's ancestor Werner on the Speyer bishop Einhard from the year 913 was still present in the Speyer diocese. Possibly the decisive reason for the sponsorship of Speyers lies in the Marian patronage of the cathedral. The Virgin Mary appeared as a facilitator and patron of kingship at the beginning of the millennium clearly in the foreground. The Speyer Cathedral offered the best conditions for the construction of a royal cathedral. Speyer received strong support from Konrad II and changed from a cow town (vaccina) to a city (metropolis) . Just a few days after his coronation, on September 11, 1024, Konrad gave the cathedral chapter a special favor with the donation to Jöhlingen (DKII.4). The Speyer Cathedral was most likely intended as his burial place from the start. Construction began in 1025. However, there is only one single stay of Konrad in Speyer, possibly because he wanted to spare the resources of the Speyer Cathedral or there was a lack of a spacious palace complex as an accommodation option.

Archaeological and art-historical studies show that when Konrad died in 1039 the crypts were finished and parts of the altar house and the angled towers were under construction and the foundations for the nave were laid. When Konrad died, the grave complex was sufficient for three graves. It is possible that in Konrad's burial place approaches to a transpersonal understanding of kingship become visible, in which the burial place was intended for the entire ruling house. But only under his son and successor Heinrich III. the cathedral reached a total length of 134 meters and thus towered over everything known in western Christendom.

Heir to the throne Heinrich III.

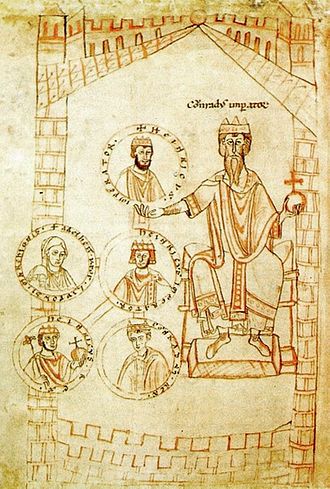

Even before his first move to Italy in February 1026, Konrad initiated measures to secure the dynasty. In the event of his death, with the approval of the princes, he appointed his nine-year-old son Heinrich as his successor. He was handed over to the care of Bishop Bruno of Augsburg . Bruno thus exercised the reign for the time of Konrad's absence. From February 1028 Konrad speaks of Heinrich "as his only son". At Easter, on April 14, 1028, Heinrich was crowned and anointed king by Archbishop Pilgrim in Aachen. By the summer of 1029, Konrad took his son Heinrich on another tour of the empire, demonstrating the splendor of the Salian dynasty. A few months later, on August 23, Konrad issued an important diploma (DK II. 29) for the Gernrode monastery . In this context, the first imperial bull of Konrad shows the inscription Heinrich on the lapel, who is not referred to as king but as Heinricus spes imperii (Heinrich, the hope of the empire). The bull is only detectable once on August 23 for Gernrode, where Adelheid from Liudolfingen ruled as abbess. The second imperial bull, which can be detected for the first time in 1033, shows the images of the emperor and king Heinrich on the obverse and thus illustrates the co-government. The reverse shows a stylized view of Rome called Aurea Roma (Golden Rome) and the leonine rhyming hexametric inscription Roma caput mundi regit orbis frena rotundi ("Rome, the head of the world, controls the reins of the world"). Through this statement, the reference to Rome, which had existed since the 9th century, was further intensified by the Salians.

Because of the imperial coronation, Konrad had to clarify his relationship with Byzantium . Since Charlemagne , there had been repeated conflicts between the two great empires because of the two-emperor problem , which was based on the universalism of imperial dignity. A marital union was designed to restore good relations between East and West. After Konrad's return in June 1027, under the leadership of Werner von Strasbourg, an embassy to the Basileus Constantine VIII broke out in September 1027 with the task of soliciting an emperor's daughter for his son Heinrich. However, the negotiations did not lead to the desired result. None of the three princesses born in purple came to marry the heir to the throne, Henry III. in question. Constantine VIII died during the negotiations. Before his death, he gave his daughter Zoe to the city prefect Romanos Argyros as wife. Konrad rejected the proposal of the new basileus to marry one of his sisters to Heinrich. The embassy returned in 1029. As a result, it brought about an improvement in relations between the two kingdoms.

After the failure of the Byzantine marriage project, Konrad sought a connection with the Anglo-Saxon-Danish royal family. For a family connection with Konrad, he ceded Schleswig with the Mark located between the Eider and Schlei . At the Bamberg Court Day in 1035, the heir to the throne was betrothed to Gunhild , the daughter of Canute the Great . The wedding took place in Nijmegen on Whitsun (June 6, 1036) of the following year. On June 29, 1036 Gunhild was crowned and anointed by the Archbishop of Cologne. In Nijmegen Konrad received more information from Margrave Boniface von Canossa Tuszien about the Italian situation, which should lead to the second Italian campaign.

Second Italian train

The rule of Conrad II over Italy was largely based on an alliance of interests with the local bishops. He tried to occupy the important dioceses with German prelates and men of his trust. The bishops thereby contributed to the bonding of the two kingdoms. In the thirties, the episcopal city rule came under increasing pressure from the highest feudal bearers of the bishops (capitanei) , who relied on numerous sub-vassals, the Valvassors . When the bishops resisted this increase in power and took the Valvassors' fiefs, unrest broke out. In particular, the energetic measures of Aribert of Milan led to a violent uprising in late 1035 / early 1036. The rebels received influx from other Valvassor groups, so that the uprising spread.

Both parties expected Konrad to clarify the situation. In December 1036, Konrad set out on his second expedition to Italy. He celebrated Christmas in Verona , while the Empress celebrated Christmas with her son and daughter-in-law in Regensburg. Konrad reached Milan via Brescia and Cremona in January or February. Konrad was received in the cathedral, but a little later the rumor was spread that Konrad wanted to withdraw the dependent diocese of Lodi from the archbishop and the city and thus damage the interests of Milan. Konrad left the city and retired to Pavia , where a court day was held in the second half of March. On the court day, the Milan Count of Otbertin brought charges against Archbishop Aribert of Milan. He was accused of numerous legal violations in the acquisition of goods and legal titles. But Aribert declared that he was not prepared to compromise or even restitute church property and that he would not accept any orders or requests in this regard. Thereupon he was arrested by Konrad for violating his duty of loyalty as a traitor and handed over to the patriarch Poppo of Aquileia and Duke Konrad of Carinthia for guarding. At the same time the imperial order was issued to return the usurped property. Aribert was able to escape from custody a little later. In response to this escape, Konrad had him deposed as archbishop without a synodal judgment and appointed a member from his court orchestra to succeed him. About Aribert which was outlawed imposed. The bishops of Vercelli , Cremona and Piacenza joined Aribert. Konrad had them arrested, tried them as traitors and sent them into exile without trial (sine iudico) . North of the Alps, he called his son with fresh troops to him. In the meantime Konrad went to Ravenna, where he is attested from April 10th to 17th, 1037 and celebrated Easter. In Ravenna he issued privileges for three Ravenna abbeys and a Venetian monastery. After May 7th, the imperial army crossed the Po at Piacenza and advanced to Milan to begin the siege. Trusting the large number, the Milanese fought in open battle. The fight brought no decision. Both parties withdrew.

During the siege, Konrad implemented a feudal law to deprive the rebellious archbishop of his vassals . On May 28, 1037 he issued the Valvassors with the now famous document regulating their fiefdoms ( Constitutio de feudis ). For the first time, certain questions of feudal law were clarified under imperial law. Arbitrary acts of the great feudal lords, the bishops, abbots, abbesses, margraves, counts and other greats who owned imperial property should be contained. The two groups of the Capitans (maiores vasvassores) and the Valvassors (eorum milites, minores vasvassores) faced these feudal lords (seniores) . The beneficiaries of the law were the maiores and minores vasvassores . It was determined that no vassal could be deprived of his fiefdom without a judgment from his peers (pares) . The Valvassors were also given the right to pass on their fiefs to sons or grandchildren. In the deed, the direct intention of the settlement between feudal lords and feudal people is announced. The law initiated a social process, at the end of which the knighthood formed from captains and valvassors was formed.

Because of the summer heat, Konrad had to break off the siege of Milan. On May 29th he celebrated Pentecost with his son and several princes in a small church near Corbetta. In the following spring, Konrad did not resume the siege. In the spring he advanced to southern Italy to assert the imperial sovereignty claims. In Spello near Foligno he celebrated with Pope Benedict IX, who has been in office since 1032 . the feast of Easter. Aribert's excommunication took place in Spello .

In southern Italy, Pandulf IV of Capua operated the expansion of his domain by force, which in particular had to suffer the secular neighbors Naples, Gaeta and Benevento and especially the monks of Montecassino . These ambitions made it necessary for Konrad to intervene. From Spello he advanced to Capua via Troia and Montecassino in April . In the middle of May Konrad celebrated Pentecost in Capua. On a court day held there, Pandulf IV lost his principality and had to go into exile in Byzantium. He transferred the principality of Capua to Waimar IV of Salerno, who also extended his rule over Amalfi, Gaeta and Sorrento. In addition, Konrad incorporated the Normans into the lower Italian statehood. At Waimar's suggestion, the Norman leader Rainulf received the county of Aversa , which had previously been subordinate to the Principality of Salerno. This was the first time, if only as an after-fief , that Norman rule was recognized by the empire. The political reorganization of the Lombard principalities led to feudal sovereignty over the principalities of Benevento, Capua and Salerno.

Konrad stayed in Capua until the end of May and started the march back along the Adriatic coast via Benevento. In July, an epidemic struck the army, which in addition to numerous princes also fell victim to Queen Gunhild , the wife of Henry III, and Duke Hermann IV of Swabia . Due to the high losses, Konrad decided to accelerate his retreat and leave Italy.

Death and succession

In the winter of 1038/1039 Konrad was busy with peacekeeping and legal safeguards in eastern Saxony. He celebrated Christmas in the Palatinate of Goslar . From the end of February to the end of May 1039, Konrad was sick in Nijmegen. The last two (received) certificates were issued there. At the end of May he moved to the episcopal city of Utrecht to celebrate Pentecost on June 3rd.

The death occurred suddenly and surprisingly in the circle of his family and the bishops around him. The common cause of his death is gout (podagra) . According to a Milan source from the middle of the 11th century, Konrad had already had foot problems and had returned from Italy with aching joints. In the Dom Tower in Utrecht , his body was laid out and, probably, the Rhine transferred there in solemn procession by boat in the home. In various episcopal cities on the Rhine, including Cologne, Mainz and Worms, the deceased was brought to the local churches with the participation of the population. One month after the ruler's death, the funeral procession reached Speyer on July 3 , where the burial took place.

According to the court historiographer Wipo , the grief over the death of the emperor is said to have been deep and general (tantas lamentationes universorum) . For Konrad he composed a funeral song (cantilena lamentationum) and placed the death of the ruler in connection with the death of other family members. The unknown author of the Hildesheim Annals reported a completely different reaction of the population to Konrad's death . The annalist noted the hard-heartedness and callousness of the people, of whom not a single one broke into sighs and tears at the death of the emperor and head of the whole world (tocius orbis caput) . Through edifying reflections on the inexplicability of God's advice, the rapid transience of a glorious ruler's life and the securing of salvation through church intercession, he used his presentation to settle accounts with the human race and its hardness and insensitivity.

The anniversary of the death of Konrad was recorded more often than any other Salier with at least 26 necrologies . His was commemorated in liturgical form in Fulda, Prüm, Mainz, Salzburg, Freising, Bamberg, Bremen, Paderborn and Montecassino, among others. On May 21, 1040, Heinrich III. the Utrecht Cathedral an important foundation for the salvation of his father's soul. His wife Gisela died almost four years later in Goslar and was transferred to Speyer by her son.

The transition of rule from the first to the second Salian ruler went smoothly and was the only safe change of the throne in Ottonian-Salian history. Henry III. was adequately prepared by Konrad for his future tasks as heir to the throne through the designation and elevation to Duke of Bavaria, the coronation of Aachen, the transfer of the Duchy of Swabia to the acquisition of Burgundy. As an already ordained king, he was able to gain experience in government early on. In 1031 he made an independent peace with the Hungarians and two years later successfully led a military enterprise against Udalrich of Bohemia. Heinrich continued the rule of Conrad II. In the given way and ensured a hitherto unknown exaltation of the kingship.

effect

Judgments of medieval historiography

The court historiographer Wipo began his “Gesta Chuonradi II. Imperatoris” immediately after Konrad's death and dedicated it to his son Heinrich. In his “Gesta”, Wipo dealt with the beginning of the government, the Italian trains, the drama of Duke Ernst of Swabia and the acquisition of Burgundy as four main themes. Wipo particularly emphasized Gisela's Carolingian origins and was therefore able to compare Konrad directly with Charlemagne. But this comparison also meant to legitimize the Salian kingship in the best possible way, since in the Middle Ages Charles was considered an ideal ruler, a role model that a king had to emulate. For Wipo no ruler since Karl was more worthy than Konrad. That is why the proverb came up about Karl's stirrups hanging on Konrad's saddles (“Konrad therefore rides with Charles, the king, stirrups”). In his lament for the dead, he called Konrad the head of the world ( caput mundi ), thereby expressing the king's claim to hegemony. Wipo describes Konrad as a powerful warlord and great judge who seems to be little concerned with spiritual matters. He reports in detail on Konrad's political feats, but fails to mention ecclesiastical matters such as the founding of the Limburg monastery, the Synod of Trebur or the Gandersheim dispute. With the assumption of power by the first Salier, Wipo perceived a turning point. The last Liudolfinger left the empire in a state of peace and security. But his childless death had brought about the danger of strife and chaos. Konrad had averted this danger and given the empire a new reputation ( rem publicam honestavit ). Konrad "made a healthy cut in the state, namely in the Roman Empire" and Heinrich III. healed the cut with sensible measures.

Wipo rarely criticizes Konrad. However, this does not apply to church affairs: Konrad was a Simonist (c. 8), he lent an imperial abbey to a layman (c. 11), and he punished bishops without a previous judgment from God (c. 35). Konrad has no higher education, no knowledge of the litterae (letters).

The contemporary author of the Chronicle of Novalese regarded Konrad as inexperienced in all sciences and as an ignorant, bumbling person (per omnia litterarum inscius atque idiota) . According to Rodulfus Glaber's judgment , Konrad II was “fide non multum firmus”. According to Glaber, with the help of the devil, Konrad was promoted to emperor at his instigation. In the circles of the reform papacy, Humbert von Silva Candida and Petrus Damiani criticized Konrad indirectly. In their opinion, only Heinrich III. the simony declared war, which indirectly but clearly accused Konrad II of this offense. The subsequent publicists of the investiture dispute lost interest in Konrad and almost only mentioned him as the father of Heinrich III for genealogical reasons.

Konrad II in research

The historians of the 19th century were interested in a strong monarchical central power and therefore looked for the reasons for the late emergence of the German nation state. The kings and emperors were seen as early representatives of a strong monarchical power that is also longed for today. In the course of the Middle Ages, however, the emperors lost this position of power. The papacy and the princes were held responsible for this. For the Protestant, nationally-minded German historiography, they were considered the "gravedigger of the German royal power".

The comparison between Heinrich II and Konrad II is a popular topic in medieval research. For the national-liberal historiography in the 19th century, the pious Ottonen was followed by the energetic, completely amateur-thinking Salier. For nationally-minded historians, Konrad was more likely to use the sword than the pen, was not offended by excessive Latin education and was not at the mercy of the clergy's intrigues. The alleged churchlessness of Konrad was seen as a feature of powerful rule. Harry Bresslau , the best expert on the subject, was decisive for this judgment . According to Bresslau, “the German-Roman empire, never before and never afterwards, had such a thoroughly secular character as it did in the decade and a half during which the crown held the high head of Konrad II. decorated ”. For him, Konrad was "the most unspiritual of all German emperors." Bresslau's image of history remained predominant for a long time. Above all, Karl Hampe contributed to its dissemination in 1932 in his book The High Middle Ages . According to his judgment, Konrad was able to lead his kingship on the basis inherited from his predecessor to a significant amount of power as “a full-fledged layman with a fist who knows how to handle swords, sober clairvoyance and a healthy sense of strength [...]. Konrad was "perhaps the most cohesive and strong-willed ruler of the entire German Middle Ages." The French church historian Augustin Fliche went much further . For him, Konrad was a "sovereign sans foi" (a ruler without faith).

After the Second World War, Theodor Schieffer undertook an article in 1951 to reassess the personality of Konrad and his church politics. According to Schieffer, Konrad's image suffered from a “revaluation” in history that began soon after his death and subjected his governmental actions to harsh criticism, even though they had not been objected to during his lifetime. Schieffer drew attention to the continuity of politics in the transition from the Ottonian to the Salic dynasty and thus cleared the picture of the “double overpainting by the 11th and 19th centuries”. While Henry II soon seized the legend and transfigured him into a saint, Konrad was viewed much more critically. The reform ideas that came into play after 1039 had an impact on the reign of Konrad; Heinrich II, who was later in time, was no longer criticized. According to Schieffer, Konrad II built on the foundations that the Ottonians and especially Heinrich II had laid, a change of course was not carried out.

By Hartmut Hoffmann (1993), the question was taken up again, like Conrad's church policy should be assessed and how it differed from Henry II.. For Hoffmann, the image goes back "from the 'unreligious' or, to put it more cautiously, from the not very pious Conrad II on Wipo's Gesta Chuonradi". Hoffmann clearly set Salier apart from the highly educated and ecclesiastical Henry II as an irreligious layman who was little affected by spiritual things, as a rex idiota. Konrad was therefore a "non-systemic figure".

Franz-Reiner Erkens reiterated Schieffer's opinion in his biography (1998). For Erkens, Konrad's kingship represented, at least for his northern Alpine empire, a peaceful, if not a climax, of a solid and safe monarchy of a sacred nature. This state of affairs is hardly a problem due to the lack of a serious threat, the relatively short reign of 15 years noticeable change in church and society as well as a personality with impact have been brought about together.

Herwig Wolfram described Konrad in his biography (2000) as a “thoroughbred politician” whose most prominent trait was his pragmatism. Wolfram's particular interest is in the field of "politics"; the ways and possibilities of the ruler to pursue his goals and resolve conflicts.

In his overview, which has been published several times, Egon Boshof (2008) rates the “strengthening of the royal authority internally and the consolidation of the reputation of the empire externally” as the great achievement of the first Salier.

swell

- Johann Friedrich Böhmer , Heinrich Appelt : Regesta Imperii III, 1. The Regesta of the Empire under Konrad II. Böhlau, Cologne et al. 1951.

- Thietmar von Merseburg, Chronicle (= Freiherr vom Stein memorial edition. Vol. 9). Retransmitted and explained by Werner Trillmich . With an addendum by Steffen Patzold . 9th, bibliographically updated edition. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2011, ISBN 978-3-534-24669-4 , Latin text in Robert Holtzmann (Ed.): Scriptores rerum Germanicarum, Nova series 9: The Chronicle of Bishop Thietmar von Merseburg and their Korveier revision (Thietmari Merseburgensis episcopi Chronicon) Berlin 1935 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- Wipo : Deeds of Emperor Konrad II. In: Werner Trillmich , Rudolf Buchner (Hrsg.): Sources of the 9th and 11th centuries on the history of the Hamburg Church and the Empire (= selected sources on German history in the Middle Ages. Vol. 11). Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1961 a. ö., pp. 505-613.

literature

General representations

- Egon Boshof : The Salians. 5th updated edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2008, pp. 32-91, ISBN 3-17-020183-2 .

- Hagen Keller : Between regional boundaries and a universal horizon. Germany in the empire of the Salians and Staufers 1024 to 1250 (= Propylaea history of Germany. Vol. 2). Propylaen-Verlag, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-549-05812-8 , especially p. 89ff.

- Johannes Laudage : The Salians. The first German royal family (= Beck series. C.-H.-Beck-Wissen 2397). Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-53597-6 .

- Stefan Weinfurter : The Century of the Salians. (1024-1125). Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2004, ISBN 3-7995-0140-1 .

Biographies

- Franz-Reiner Erkens : Konrad II. (Around 990-1039). Rule and empire of the first Salier emperor . Pustet, Regensburg 1998, ISBN 3-7917-1604-2 .

- Herwig Wolfram : Konrad II. 990-1039: Emperor of three kingdoms. Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46054-2 ( review ).

- Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. In: Bernd Schneidmüller , Stefan Weinfurter (Hrsg.): The German rulers of the Middle Ages, historical portraits from Heinrich I to Maximilian I. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-50958-4 , p. 119-135 and 571f. (Bibliography).

Special studies

- Harry Bresslau : Yearbooks of the German Empire under Konrad the Second. Vol. 1: 1024-1031, Vol. 2: 1032-1039. Duncker and Humblot, Berlin 1879 and 1884 (ND 1967)

- Eckhard Müller-Mertens , Wolfgang Huschner : Reich integration as reflected in the rule of Emperor Konrad II (= research on medieval history. Vol. 35). Böhlau, Weimar 1992, ISBN 3-7400-0809-1 .

- Hartmut Hoffmann: Monk King and "rex idiota". Studies on the church politics of Heinrich II. And Konrads II. (= Monumenta Germaniae historica. Studies and texts Vol. 8). Hahn, Hannover 1993, ISBN 3-7752-5408-0 .

- Theodor Schieffer : Heinrich II. And Konrad II. The change of the historical image through the church reform of the 11th century. In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 8, 1951, pp. 384–437 ( digitized version ).

Lexicons

- Heinrich Appelt : Konrad II. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 12, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1980, ISBN 3-428-00193-1 , pp. 492-495 ( digitized version ).

- Stefan Rheingans: Konrad II .. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 4, Bautz, Herzberg 1992, ISBN 3-88309-038-7 , Sp. 400-409.

- Franz-Reiner Erkens : Konrad II. (Around 990-1039). In: Albrecht Cordes , Hans-Peter Haferkamp , Heiner Lück , Dieter Werkmüller and Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand (eds.): Concise dictionary on German legal history. Vol. 3, 17th delivery, Berlin 2014, Sp. 104-105 ( online )

Web links

- Literature by and about Konrad II in the catalog of the German National Library

- Publications on Konrad II in the Opac der Regesta Imperii

- Walter Liedtke: 04.06.1039 - Anniversary of the death of Emperor Konrad II. WDR ZeitZeichen (podcast).

Remarks

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The Century of the Salians 1024-1125. Ostfildern 2006, p. 20. See: Hans Werle: Titelherzogtum und Herzogsherrschaft. In: Journal of the Savigny Foundation for Legal History, German Department 73 (1956), pp. 225–299.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 37.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Konrad II. (Around 990-1039). Rule and empire of the first Salier emperor. Regensburg 1998, p. 29.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Konrad II. (Around 990-1039). Rule and empire of the first Salier emperor. Regensburg 1998, p. 30.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Konrad II. (Around 990-1039). Rule and empire of the first Salier emperor. Regensburg 1998, p. 35.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: Colloquium familiare - colloquium secretum - colloquium publicum. Advice on political life in the early Middle Ages. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien, Vol. 24 (1990), pp. 145–167, here: p. 165.

- ↑ Steffen Patzold: How do you prepare for a change of the throne? Thoughts on a neglected 11th century text. In: Matthias Becher (Hrsg.): The medieval succession to the throne in European comparison. Ostfildern 2017, pp. 127–162 ( online ).

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 62.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 60.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Konrad II (around 990-1039) rule and empire of the first Salier emperor. Regensburg 1998, p. 40.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 62.

- ↑ Wipo c. 2.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Konrad II (around 990-1039) rule and empire of the first Salier emperor. Regensburg 1998, p. 40.

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Demonstration and staging. Rules of the game of communication in medieval public. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien , Vol. 27 (1993), pp. 27-50, here: pp. 31-33; Andreas Büttner: From text to ritual and back - coronation rituals in sources and research. In: Andreas Büttner, Andreas Schmidt and Paul Töbelmann (eds.): Limits of ritual. Effective ranges - areas of application - research perspectives. Cologne et al. 2014, pp. 287–306, here: pp. 288–293.

- ↑ Wipo c. 3. and 5. Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 67; Ludger Körntgen: Kingdom and God's grace. On the context and function of sacred ideas in historiography and pictorial evidence of the Ottonian-Early Salian period. Berlin 2001, pp. 142ff.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: The high medieval monarchy. Accents of an unfinished reassessment. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 45 (2011) pp. 77–98, here: p. 93.

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Otto III. and Henry II in conflicts. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. and Heinrich II. A turning point. Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 77-94, here: p. 93.

- ↑ Hans Martin Schaller: The Vienna Imperial Crown - created under King Konrad III. In: The Reichskleinodien. Signs of rule of the Holy Roman Empire. Göppingen 1997, pp. 58-105; Sebastian Scholz: The Vienna Imperial Crown. A crown from the time of Conrad III? In: Hubertus Seibert, Jürgen Dendorfer (Ed.): Counts, dukes, kings. The rise of the early Hohenstaufen and the empire 1079–1125. Ostfildern 2005, pp. 341–362.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 183.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Konrad II (around 990-1039) rule and empire of the first Salier emperor. Regensburg 1998, p. 58.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 77.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 205.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 78.

- ↑ Wipo c. 7th

- ^ Egon Boshof: The Salians. 5th, updated edition, Stuttgart 2008, p. 43.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Konrad II. (Around 990-1039). Rule and empire of the first Salier emperor. Regensburg 1998, p. 71.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 114.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 117.

- ↑ Wipo c. 14th

- ^ Egon Boshof: The Salians. 5th, updated edition, Stuttgart 2008, p. 47.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Konrad II. (Around 990-1039). Rule and empire of the first Salier emperor. Regensburg 1998, p. 85.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 123.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 127.

- ↑ Hans Constantin Faussner: Royal designation right and ducal blood right. About the kingship and duchy in Baiern in the High Middle Ages. Vienna 1984, p. 28ff.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 133.

- ↑ See: Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Kaiser Dreier Reiche Munich 2000, p. 133.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, pp. 209f.

- ^ Hubertus Seibert: Libertas and Imperial Abbey. On the monastic policy of the Salian rulers. In: Stefan Weinfurter with the collaboration of Frank Martin Siefarth (Ed.): The Salier and the Reich Vol. 2: The Reich Church in the Salier period. Sigmaringen 1991, pp. 503-569, here: p. 521.

- ↑ Wipo c. 28.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The Century of the Salians 1024-1125. Ostfildern 2006, p. 60. The opposite view in: Egon Boshof: Die Salier. 5th, updated edition, Stuttgart 2008, p. 60.

- ^ Ingrid Heidrich : The deposition of Duke Adalberos of Carinthia by Emperor Konrad II. 1035. In: Historisches Jahrbuch 91 (1971), pp. 70–94.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The Century of the Salians 1024-1125. Ostfildern 2006, p. 61.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 96.

- ^ Hubertus Seibert: Libertas and Imperial Abbey. On the monastic policy of the Salian rulers. In: Stefan Weinfurter with the collaboration of Frank Martin Siefarth (Ed.): The Salier and the Reich Vol. 2: The Reich Church in the Salier period. Sigmaringen 1991, pp. 503-569, here: p. 517.

- ^ Hubertus Seibert: Libertas and Imperial Abbey. On the monastic policy of the Salian rulers. In: Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): The Salians and the Reich Vol. 2: The Reich Church in the Salier period. Sigmaringen 1991, pp. 503-569, here: p. 518.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: Legitimation of rule and the changing authority of the king: The Salier and their cathedral in Speyer. In: Stefan Weinfurter with the collaboration of Frank Martin Siefarth (Ed.): Die Salier und das Reich, Vol. 1. Sigmaringen 1991, pp. 55–96, here: p. 68.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: Legitimation of rule and the changing authority of the king: The Salier and their cathedral in Speyer. In: Stefan Weinfurter with the assistance of Frank Martin Siefarth (ed.): Die Salier und das Reich, Vol. 1. Sigmaringen 1991, pp. 55–96, here: p. 67.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 328.

- ↑ Wipo c. 9.

- ^ Egon Boshof, The Salians . 5th, updated edition, Stuttgart 2008, p. 44.

- ^ Egon Boshof, The Salians. 5th, updated edition, Stuttgart 2008, p. 71.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 234.

- ↑ See: Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 244.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Konrad II. (Around 990-1039). Rule and empire of the first Salier emperor. Regensburg 1998, p. 154.

- ↑ Wipo c. 21st

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Konrad II. (Around 990-1039). Rule and empire of the first Salier emperor. Regensburg 1998, p. 167.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Konrad II. (Around 990-1039). Rule and empire of the first Salier emperor. Regensburg 1998, p. 170.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Konrad II. (Around 990-1039). Rule and empire of the first Salier emperor. Regensburg 1998, p. 216. See also: Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 181; Caspar Ehlers: Metropolis Germaniae. Studies on the importance of Speyer for royalty (751–1250). Göttingen 1996, p. 77.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter, The Century of the Salians 1024–1125. Ostfildern 2006, p. 44f.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The Century of the Salians 1024-1125. Ostfildern 2006, p. 45.

- ↑ Caspar Ehlers: Metropolis Germaniae. Studies on the importance of Speyer for royalty (751–1250). Göttingen 1996, p. 79.

- ↑ Hans Erich Kubach, Walter Haas: The Speyer Cathedral. 3 volumes, Munich 1972.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The Century of the Salians 1024-1125. Ostfildern 2006, p. 46.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 159.

- ↑ Ante tui vultum mea defleo crimina multum. Da veniam, merear, cuius sum munere caesar. Pectore cum mundo, regina, precamina fundo aeternae pacis et propter gaudia lucis. see. the translation: Stefan Weinfurter: Configurations of order in conflict. The example of Henry III. In: Jürgen Petersohn (Ed.): Mediaevalia Augiensia. Research on the history of the Middle Ages. Stuttgart 2001, pp. 79-100, here: p. 86.

- ↑ DK II. 244. See Hagen Keller: The 'Edictum de beneficiis' Konrad II and the development of feudalism in the first half of the 11th century. In: Il feudalismo nell'alto medioevo (Settimane di studio del Centro italiano di studi sull'alto medioevo 47) Spoleto 2000, pp. 227-261.