Architecture of spa buildings

Spa buildings are used for recreation and leisure activities and can be found in health resorts . The architecture of these buildings is also called spa architecture , even if it is not a uniform architectural style , but a collective term for a type of building with the function of a cure .

The building type has been developed since the 17th century, its heyday was the 19th century. The term spa architecture refers primarily to the architecture of the spas inland, while the term spa architecture has established itself for the seaside resorts on the coast . Since the early 19th century, there have been many parallels between the architectural design language of spas and seaside baths.

Early forerunners in antiquity and the Middle Ages

Health resorts already existed in ancient times . They owe their origin to the medicinal properties of the hot springs, which were already known back then. In the center of Roman health resorts were thermal baths , which were generally less symmetrical than the large imperial thermal baths in the cities, because they had to adapt to the topography of the thermal spring area. The most important Roman spa town was Baiae in the Gulf of Naples. In Germany, the spa towns of Aachen , Wiesbaden , Baden-Baden and Badenweiler were founded in the first century AD . In Switzerland, St. Moritz experienced its first boom with the healing spring discovered by Paracelsus .

After this heyday, bathing became quiet in Europe. Elaborate baths like in Roman antiquity did not exist in the Middle Ages . The crusaders brought the Islamic bathing culture with them from the Orient . With the rise of the bourgeoisie in the cities in the 12th century, public bathhouses emerged , but they did not produce their own architectural language and could not be distinguished from residential buildings from the outside. The great time of the bathing industry ended with the Thirty Years War .

Boom

The spa industry experienced an upswing in the 15th and 16th centuries and became an important economic factor.

When the spa industry gained in importance in the second half of the 17th century, the drinking cure became fashionable instead of the previous spa treatment . If a health resort could not keep up with this development and carry out cost-intensive structural changes, it would become a poor or peasant bath. Important ancient foundations such as Baden-Baden and Wiesbaden were affected.

In the baroque era there were important new trends with the princely baths. The role models can be found in palace construction. The best preserved example in Germany is Brückenau . Prince-Bishop Amand von Buseck expanded the place from 1747. A spa facility was built on a terraced hill about three kilometers from the city. A central axis in the form of a lime tree avenue framed by pavilions leads to the castle-like building in the valley . The model for the Brückenau complex was Marly-le-Roi Castle , Ludwig XIV's summer palace, built between 1679 and 1687 .

The most important spa towns of the 18th century are not the relatively small royal baths , but Bath in England and Aachen. Both cities played a decisive role in the development of spa architecture in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The spa system in Aachen has been recovering from the consequences of the Thirty Years' War since the late 17th century. The spa doctor François Blondel had a decisive influence on this and made Aachen known as a spa in Europe with his balneological books. Blondel's most important achievements were the expansion of the drinking cure and his involvement in the design of the new spa facilities.

Aachen developed into the leading fashion spa on the continent and maintained this position until the French occupation at the end of the 18th century. The most important spa building of the 18th century is the " New Redoute ", which was built from 1782 to 1786 according to plans by the architect Jakob Couven . As the center of social life, the building is a direct forerunner of the spa house type that was widespread in the 19th century.

Flowering 19th century

Since around 1800, public construction tasks have generally become more differentiated. This concerned a large number of buildings for social events. In the health resorts there was a concentration of buildings for education, communication and leisure for the large number of guests. Specific construction tasks such as the spa house , drinking hall and thermal baths arose . There were also landscaped gardens, hotels and villas, but also theaters, museums, mountain railways and observation towers.

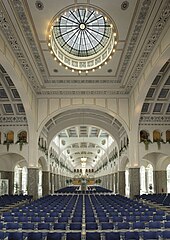

The spa architecture experienced a greater specialization in the 19th century. The spa buildings no longer combined all tasks such as lounges, bathrooms and lodging rooms under one roof, as was usually the case in the Baroque era. The 19th century Kurhaus is a building that is exclusively intended for social events. Baths and lodging rooms are moved to bathhouses and hotels specially built for this purpose. In the center of the Kurhaus is a large and representative hall . There are also several side rooms for a wide variety of tasks, such as gambling, reading and restaurant operations.

The first Kurhaus new coinage was not preserved Wiesbaden Kurhaus of Christian Zai , the 1808 was to 1810th The oldest preserved Kurhaus is the Kurhaus Baden-Baden , built between 1822 and 1824 according to plans by the Grand Ducal Building Director Friedrich Weinbrenner . The three-part system is 140 meters long. The building consists of a large central hall. In the north and south this is flanked by pavilions for the theater and restaurant. Galleries are located between these three large structures, which are clearly visible in the floor plan.

Drinking halls emerged from the fountains that became common after the introduction of the drinking cure in the Baroque era. These offered the spa guests the opportunity to fill their drinking cups with thermal water . There were thermal fountains in all German spa towns in the 17th century. Pavilions were built over the fountain . Towards the end of the 18th century there was a new development. The well houses were extended by gallery wings. In the 19th century the pump room was a well-known type of building.

Large thermal baths emerged in Germany, especially after the gambling ban in 1872. The spa towns invested in bathing houses in order to remain attractive to the spa guests. The most important thermal bath of this time is the Friedrichsbad in Baden-Baden, which was built according to plans by Karl Dernfeld . Direct models are the Raitzenbad in Budapest and the Graf-Eberhardsbad (today Palais Thermal ) in Bad Wildbad .

A stylistic transition from the 19th to the 20th century is the largest enclosed fountain hall in Europe (3,240 square meters) in the Bavarian state bath of Bad Kissingen . It was built in 1910/1911 by the architect Max Littmann on behalf of the Prince Regent Luitpold .

20th century

The social health and the changed travel behavior of the people in the 20th century demanded new architectural solutions.

The first examples of modern spa architecture can be found in the 1930s. One of the earliest representatives of the new objectivity is the new drinking hall in Bad Wildbad , which Reinhold Schuler , building officer in the Württemberg finance ministry, and Otto Kuhn , president of the building department of the finance ministry, planned in 1933. The Nazi regime's neoclassical conception of art prevented it from spreading further.

After 1945 - apart from a few outstanding individual solutions (e.g. Kurhaus in Badenweiler by Klaus Humpert , 1970–1972) - no successors in the true sense of the word were developed for the categories of Kurhaus, Trinkhalle and Kurbad .

literature

- Angelika Baeumerth: royal castle versus festival temple. On the architecture of the Kursaal building in Bad Homburg vor der Höhe. (= Messages from the Association for History and Regional Studies in Bad Homburg vor der Höhe. Volume 38). Jonas, Marburg 1990, ISBN 3-89445-104-1 . (At the same time dissertation at the University of Marburg 1990).

- Rolf Bothe (Hrsg.): Spa towns in Germany. On the history of a building type. Frölich & Kaufmann, Berlin 1984, ISBN 3-88725-002-8 .

- Matthias Bitz: Bathing in Southwest Germany. 1550 to 1840. On the change in society and architecture. (= Scientific writings in the Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Dr. Schulz-Kirchner. Series 9: Historical contributions. 108). Schulz-Kirchner, Idstein 1989, ISBN 3-925196-68-4 . (also dissertation at the University of Mainz in 1988)

- Ulrich Coenen: Bathing in Baden-Baden. From the Roman facilities to the modern Caracallatherme. In: The Ortenau. Publications of the Historical Association for Central Baden. 81, 2001, ISSN 0342-1503 , pp. 189-228.

- Ulrich Coenen: From Aquae to Baden-Baden. The building history of the city and its contribution to the development of the spa architecture. Mainz, Aachen 2008, ISBN 978-3-8107-0023-0 .

- Ulrich Coenen: The spa town as a world cultural heritage. In: Badische Heimat. 3, 2010, pp. 609-618.

- Ulrich Coenen: Spa architecture in Germany. In: Badische Heimat. 3, 2010, pp. 619-637.

- Thomas Föhl: Wildbad. The chronicle of a spa town as building history. Druckhaus Müller, Neuenbürg 1988 DNB 943858704 (At the same time short version of dissertation at FU Berlin 1986).

- Carmen Putschky: Wilhelmsbad, Hofgeismar and Nenndorf. Three health resorts of Wilhelm I of Hessen-Kassel. Dissertation at the University of Marburg 2000 DNB 965599655 .

- Ulrich Rosseaux: Urbanity - Therapy - Entertainment. On the historical significance of the spa and spa towns in the 19th century. In: City of Baden-Baden (Ed.): Baden-Baden. 19th century spa town. Application of the city of Baden-Baden as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Results of the workshop in Palais Biron on November 22, 2008. Stadtverwaltung Baden-Baden, Baden-Baden 2009, pp. 49–51.

- Petra Simon, Margrit Behrens: Spa treatment and health spa. Buildings in German baths 1780–1920. Diederichs, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-424-00958-X .

- Monika Steinhauser: The European fashion bath of the 19th century. Baden-Baden, a residence of happiness. In: Ludwig Grote (Hrsg.): The German city in the 19th century. Urban planning and building design in the industrial age. (= Studies on the Art of the Nineteenth Century. 24). Prestel, Munich 1974, ISBN 3-7913-0051-2 , pp. 95-128.

- Anke Ziegler: German spa towns are changing. From the beginning to the ideal type in the 19th century. (= European university publications. Series 37: Architecture. 26). Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 2004, ISBN 3-631-52543-5 . (also dissertation at the University of Kaiserslautern 2003)