Mössinger general strike

As Mössinger general strike of the time of the actions referred to a large part of the working class textile industry dominated Württemberg industrial village Mössingen are considered of Germany's only attempt to power of Adolf Hitler on the first day after his appointment as Reich Chancellor (January 30, 1933) by a general strike to thwart .

Almost simultaneously with the beginning of the formal rule of National Socialism , the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) - which was to be banned four weeks later by the Reichstag Fire Ordinance - called for a "mass strike" in a leaflet intended for nationwide distribution . Only workers in Mössingen answered this call.

The attempt to implement the general strike was due, among other things, to the low response to the call for a strike in the entire German Reich as well as the rapid destruction of this first collective resistance action against the Nazi regime in power in the relatively small community of around 4,200 inhabitants history and remained largely hidden from the public eye for more than five decades.

Call of the Württemberg KPD leadership to a mass strike

Immediately after the last Reich President of the Weimar Republic , Paul von Hindenburg , had appointed the "Führer" of the NSDAP , Adolf Hitler, as Reich Chancellor, the Württemberg district leadership of the KPD in Stuttgart distributed a leaflet about the mass strike against Hitler and the impending NS -Dictatorship called. The Reichstag member Albert Buchmann was responsible for drawing. The hope for the strike call issued by the KPD throughout the Reich was that it would still be able to avert the rule of National Socialism - following the example of the general strike against the right-wing extremist Kapp Putsch in 1920, which paralyzed the infrastructure of all of Germany and thus the still young one Weimar's pluralistic democracy had saved.

Preparation and strike

First day: Monday, January 30, 1933

On the evening of January 30, 1933, over 200 members of several Mössingen workers' associations gathered in the local Langgass gym . This meeting was called by the chairman of the about twenty party members of the Mössingen KPD local group, the painter Martin Maier , after he was sent by a courier from Reutlingen , 20 km northeast of Mössingen - to this day the largest city in the vicinity and at that time the seat of one Württemberg Oberamt - had learned of the strike call.

Those present decided to reactivate an anti-fascist action group formed the previous year and called for a follow-up meeting the next day at 12 noon at the same place, where further measures should be discussed. The conclusion of this preparatory meeting was an evening demonstration of the anti-fascist action by the community, at which slogans such as "Hitler verrecke!" And "Hitler means war!" Were chanted.

Second day: Tuesday, January 31, 1933

On the morning of January 31st, Martin Maier brought the subdistrict of the KPD, Fritz Wandel , from Reutlingen to Mössingen for political support. When they arrived in front of the gym around 12.30 p.m., the two met around 100 anti-fascists , mostly unemployed and craftsmen, who after a brief discussion decided to mobilize the workforce of the Mössing companies for a general strike. First, the still small demonstration marched behind a banner that had been prepared that night and read “Out to the mass strike ” to the Pausa company , a colored weaving mill in which a vote on participation in the general strike was taking place. When the demonstrators arrived at 12:45 p.m., one of the two departments had spoken out in favor of participating in the strike , while the majority of the other was against. At 1 p.m. there should be another, but this time joint, vote by all employees. Fritz Wandel used the remaining time to give a speech in which he strongly advocated the general strike against the Nazis . The workers at Pausa then voted for the strike by 53 votes against 42. The company owners, the brothers Artur and Felix Löwenstein, who, as Jews, also had an interest in the overthrow of the Nazi regime, approved this result of the vote and released the workforce for the afternoon.

The majority of the Pausa employees joined the demonstration, the next destination of which was the Merz tricot factory , Mössingen's largest industrial company with around 400 employees at the time. Meanwhile, other citizens of Mössingen and the surrounding villages had lined up in the demonstration, which had grown to around 600 people by the time it arrived at Merz around 2 p.m.

The strikers penetrated the factory premises and occupied the premises. After a few arguments, they finally succeeded in persuading the workers in the weaving room to turn off the machines. In the sewing room, where almost only women worked, this was not so easy to achieve. After more and more demonstrators got into the sewing room, it was no longer possible to continue working there due to the commotion and loud arguments. The workers who did not quit voluntarily were dragged from their seats and pushed outside.

In the meantime, the company owner Otto Merz had informed the Mössing mayor Karl Jaggy by telephone about the incidents in his company and asked him to request external police officers. Jaggy was not ready for that for the time being. He thought it would deal with itself and advised to wait. Merz was not satisfied with this and even requested police support from the Oberamt in Rottenburg , which then dispatched a unit of the closest Reutlingen riot police to Mössingen. In addition, Merz alerted the management of the third Mössingen textile company, the Burkhardt colored weaving mill, and informed them about the processes in his company.

The arguments at Merz lasted more than an hour. Then the demonstration of the striking anti-fascists, meanwhile a good 800 strong, marched on to the Burkhardt company. There, the management had had the factory gate closed, forewarned by Merz. Between 50 and 60 demonstrators climbed over - there were verbal arguments with the supervisory staff - others tried to force open the gate. Red flags were waved in front of the factory windows . Few workers in the company stopped working. Finally, the strike management called off the attempt to break into the company premises and ordered a withdrawal to the gym.

During their retreat the demonstrators came to 16 clock on the now arrived from Reutlingen 40-man, armed with pistols and truncheons season of raiding the police who blocked their way. Now the anti-fascists could assume that there had not been a strike against Hitler's takeover of power in the surrounding towns, since the police would otherwise have been tied up in much larger operations elsewhere and would hardly have been able to provide resources for small Mössingen. So it was decided to break up the demonstration. The majority of the strikers evaded the identification and fled across the fields.

The historian Frank Meier emphasizes that the events in Mössingen were "unique" as regards January 31, 1933, but not with regard to resistance actions in general between that day and the day when the Enabling Act was passed on March 24, 1933. This was shown by activities below the level of a general strike in other cities in the region such as Balingen and Mühlacker .

Consequences for the strikers

The first strikers were arrested that same evening. In the following days there were further arrests , not only in Mössingen, but also in surrounding communities such as Belsen , Nehren or Talheim . Many of those involved in the strike, especially those workers from the Merz company who had joined the demonstration and could not plead that they had been involuntarily forced off their work, were dismissed without notice.

In the end there were criminal proceedings against 98 workers who had been distributed to various prisons in Württemberg . Most of the charges were for breach of the peace . Seven defendants were considered " ringleaders " and were tried before the criminal senate of the Higher Regional Court in Stuttgart on charges of "preparing for high treason in unity with aggravated breach of the peace": Master glazier Jakob Stotz (1899–1975), who was trained by the Social Democrats had switched to Communists, was a leading member of the Mössinger KPD. Jakob Textor (1908–2010), a painter by profession, an activist of the local labor movement and enthusiastic worker sportsman , had already written on a wall for the Reichstag election in November 1932 : “If you vote for Hitler, you choose war!” Hermann Ayen sat in the building from 1919 to 1933 Mössinger municipal council - first for the SPD, from 1922 for the KPD. Until 1924 he was also chairman of the local KPD group. In addition to him, his two sons Paul and Eugen were also indicted. The painter Martin Maier was the local chairman of the KPD in Mössingen in 1933. Its namesake Martin Maier, the cashier of the Mössinger Konsumverein ("Konsum-Maier"), a trained Wagner , had belonged to the provisional workers, farmers and craftsmen's council formed in Mössingen during the November Revolution after the First World War and was in 1919 with four others Social Democrats for the SPD drafted into the newly elected Mössingen municipal council, of which he was a member until 1933.

77 men and three women were from the - not in 1933 by the Nazis conformist - Justice sentenced to prison terms of between three months and 2½ years. The hardest hit was the KPD sub-district leader and member of the Reutlingen municipal council, Fritz Wandel : He was arrested at the beginning of March and, as the main speaker in the strike campaigns in October 1933, was sentenced to 4 ½ years in solitary confinement in the Rottenburg correctional facility on charges of “high treason” imprisoned. After "serving" this detention, the rulers continued to regard him as a communist Nazi opponent and was initially interned as a so-called " protective prisoner " for five months in the Welzheim Gestapo camp before he was transferred from there to the Dachau concentration camp , where he spent approx was held prisoner for six years. After that he was forcibly used in the Penal Battalion 999 until the end of the Second World War .

Post-history

The attempt at the general strike in Mössingen was deliberately kept quiet by the National Socialists. Most Mössingers integrated themselves into the everyday life of the so-called “Third Reich” in the years that followed and came to terms with the situation. The Jewish owners of the Pausa company, the first company on strike on January 31, 1933, were forced to sell the traditional and renowned company significantly below its value in the course of the so-called " Aryanization of Jewish property" in 1936. A little later , due to the increasing institutionalized exclusion of Jews in Germany , they emigrated to Great Britain , before the anti-Semitic measures of the Nazi regime during the Second World War resulted in the industrial genocide known today as the Holocaust .

The seven "ringleaders" survived the Nazi dictatorship and the Second World War . Most of them started doing political work for the KPD, which was initially legal again after 1945 . After the end of the Nazi dictatorship, Jakob Stotz was appointed provisional mayor of Mössingens by the French occupying forces and was in office for a few months, after which he continued to work in the municipal council for the KPD until 1955. Jakob-Stotz-Platz in Mössingen has been named after him since 1985, and a plaque on it commemorates his work. Between 1945 and 1948, Wandel played an important role in the reconstruction of democracy in Reutlingen, which, like Mössingen, was under French occupation as the “third deputy” of the mayor and head of the housing office. In the first local council elections in Mössingen, Hermann Ayen was the top candidate in a list that was positioned to the left of the KPD. His son Eugen also rejoined his old party friends after his return from captivity. Paul Ayen was caught doing a leaflet campaign after serving his prison sentence, but was able to evade arrest and emigrated to Switzerland. In 1936 he joined the International Brigades that fought for the Republic against the Franco dictatorship in the Spanish Civil War . After the victory of the Falange under Franco , Paul Ayen fled again to Switzerland, where he stayed until the end of the war. Then he too returned to Germany and became active with the Tübingen communists. Jakob Textor was also caught distributing leaflets after his release from prison and found it difficult to talk his way out of the matter, whereupon he temporarily stopped his political activity. After 5 years of participation in the war, he returned to Mössingen in 1945 and, when the parties were re-admitted, became a member of the KPD. When they were banned in 1956, Jakob Textor ended his political engagement. The former local group chairman Martin Maier, who was seriously ill during his one year and nine months imprisonment, so that his right lower leg had to be amputated, returned to Mössingen, but no longer appeared politically. "Konsum-Maier" was removed from his office in the consumer association in May 1933 and became a farmer. After the war, the French occupying forces appointed him to the advisory committee that helped them with the administration. In 1946 he was re-elected for the KPD in the Mössing municipal council, to which he belonged until 1948.

The events of the end of January 1933 and the subsequent period up to 1945 in Mössingen were in the media, which was founded in 1949 Federal Republic of Germany (in the locally based) during the Cold War , which even before the reconstitution of two different German state structure was used in a Shrouded in a cloak of silence . In the anti-communist mood of the West German public in the Adenauer - era and long after many of the initiated by Communist general strike attempt of 1933 was, especially after the 1956 adopted KPD ban as inadmissible.

Only by the West Berlin Red Book Publishing in 1982 under the title There's nowhere nothing been out here published results of a research group at the Ludwig-Uhland Institute for Empirical Cultural Studies at the Eberhard Karls University of Tuebingen and a documentary from 1983 with the same title (see the section on literature and documentary film ), the decades-long silence of the public and the bearers of public opinion on the events of the last two days of January 1933 in the small Swabian town was broken, and the Mössing general strike was wrested from oblivion beyond the region.

In 1983, 1993, 2003 and 2013, on the 50th, 60th, 70th and 80th anniversaries of the Mössingen general strike, supra-regional anti-fascist demonstrations and rallies took place in Mössingen, which has now grown to the third largest city in the Tübingen district with around 20,000 inhabitants . to which the Association of Victims of the Nazi Regime - Bund der Antifaschisten ( VVN-BdA ) - called for various trade unions and peace initiatives . At these rallies, the actions of 1933 were remembered and current references were made.

On the 70th anniversary of the general strike in 2003, an exhibition on the subject was opened in Mössingen. Also present was the last surviving - once convicted - participant in the strike, Jakob Textor, who was 94 years old at the time and who had made the banner “Out to the mass strike”. - Textor died in January 2010 shortly before his 102nd birthday.

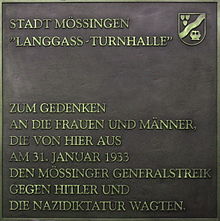

In October 2003, after many political conflicts in which, in contrast to the final stage of today Weimar Republic rather conservative dominated region a memorial plaque at the gym opened, which had formed the starting point of Mössinger general strike. The plaque was enforced in particular against the resistance of the regional and local CDU , initially also of the mayor Werner Fifka, who was in office from 1998 to 2010 (at that time still SPD ).

The inscription on this memorial reads: "In memory of the women and men who dared the Mössing general strike against Hitler and the Nazi dictatorship from here on January 31, 1933."

The entrepreneur Otto Merz sen. (1886–1964), who initiated the police breaking up the general strike by alerting the Oberamt in Rottenburg, made the municipality of Mössingen an honorary citizen in 1956, on the grounds that he had contributed to the fact that in the mid-1920s through his jersey factory Mössingen jobs were created, and so the local economic power was promoted. At the demonstration and rally organized by various trade unions and the VVN-BdA on February 2, 2013 on the 80th anniversary of the Mössing general strike, the renaming of Otto-Merz-Strasse, named after the entrepreneur, to Jakob-Textor-Strasse was demanded.

Stage processing

In the course of 2012, the Lindenhof Theater from Melchingen , about eleven kilometers from Mössingen, began to deal with the historical general strike material. After extensive research, Franz Xaver Ott wrote the play A Village in Resistance and took over the dramaturgical direction of the stage work conceived as a “Concerted Play for the Mössinger General Strike 1933” . The implementation of the play was under the patronage of Winfried Kretschmann , who has been Minister-President of Baden-Württemberg since May 2011. In cooperation with the city of Mössingen and various local schools this stage adaptation was on 11 May 2013, the sold-out former Pausa Arch Hall, directed by Philipp Becker premiered . In addition to the ensemble of Theater Lindenhof, around 40 musicians and 100 amateur actors from Mössingen's citizenship took part, including Andrea Ayen, a daughter of the general strike participant Paul Ayen.

Even in the run-up to the premiere, the piece had attracted attention in the feature sections of the national media. By September 2013, A Village in the Resistance was performed more than twenty times in front of a sold-out house. There were also two performances at the renowned Ruhr Festival in Recklinghausen in June , which received positive reviews . In June 2014, the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media , State Minister Monika Grütters, awarded the play the BKM Prize for Cultural Education . A film team led by the filmmaker Katharina Thoms accompanied the rehearsals of the play. This resulted in the documentary about the Mössing general strike "Resistance is a duty".

Literature and film

literature

- Hans-Joachim Althaus u. a. (Ed.): Nowhere was there anything except here. The “red Mössingen” in the general strike against Hitler. History of a Swabian workers' village . Berlin 1982, ISBN 3-88022-242-8 .

- Robert Scheyhing : The Mössingen general strike at the end of January 1933 . In: Journal for Württemberg State History, Volume 45 (1986), pp. 352–362.

- Hermann Berner, Bernd Jürgen Warneken (eds.): “There was nothing there except here!” The “red Mössingen” in the general strike against Hitler . Extended new edition with the support of Rotbuch Verlag, which published the first edition. Mössingen 2012, ISBN 978-3-89376-140-1 .

- Franziska Blum: The Mössingen general strike on January 31, 1933: Left resistance from the very beginning , in: Peter Steinbach , Thomas Stöckle, Sibylle Thelen, Reinhold Weber (ed.): Disenfranchised - persecuted - destroyed. Nazi history and culture of remembrance in the south-west of Germany (writings on political regional studies of Baden-Württemberg, Volume 45); State Center for Civic Education Baden-Württemberg, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2016, pp. 31–59, ISBN 978-3-945414-20-0 .

- Gertrud Döffinger, Hans-Joachim Althaus: Mössingen. Workers' policy after 1945. Tübingen 1990, ISBN 3-925340-63-7 . The book is part of the "Studies & Materials" series of the Tübingen Ludwig Uhland Institute for Empirical Cultural Studies on behalf of the Tübinger Vereinigung für Volkskunde e. V. (TVV) and deals with the consequences of the Mössingen general strike for Mössingen (workers) politics, based on interviews with contemporary witnesses and archive sources.

- Frank Meier : The “red Mössingen” in a regional comparison - possibilities and potentials of regional history . In: Siegfried Frech / Frank Meier (Hrsg.): Teaching topic state and violence. Categorical approaches and historical examples . Schwalbach am Taunus 2012, pp. 292-316, ISBN 978-3-89974-820-8 .

- Lothar Frick (Ed.): "Out to the mass strike" The Mössingen general strike of January 31, 1933 - left resistance in the Swabian province ; published in the series materials of the state center for political education Baden-Württemberg , Stuttgart 2015, ISBN 978-3-945414-23-1 . ( available online as a PDF file at lpb-bw.de, 8.8 MB)

- Wolfgang Däubler : The "Mössinger General Strike" of January 31, 1933 - practiced right of resistance? ; in the journal Arbeit und Recht , 11/2017 edition, pp. G21 – G24 ( article available online as a PDF file )

- Ewald Frie : The Mössingen general strike . In: Sigrid Hirbodian / Tjark Wegner (Ed.): Uprising, revolt, anarchy! Forms of Resistance in the German Southwest , Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2019 (Landeskundig, Volume 5), pp. 217–237, ISBN 978-3-7995-2074-4 .

Documentaries

- Nowhere was there anything but here. Documentary, Federal Republic of Germany 1983; Director: Jan Schütte

- Resistance is a must Documentary, Germany 2014 ; Director: Katharina Thoms

See also

Web links

- www.mössinger-generalstreik.de Virtual history site of the museum and the Mössingen city archive funded by the State Center for Civic Education Baden-Württemberg.

- Process files for the Mössing general strike as digital reproduction in the online offer of the Baden-Württemberg State Archive, State Archive Sigmaringen

- Multimedia presentation of the Mössing general strike in text, image, film and sound (on multimedia.hd-campus.tv), accessed on September 18, 2017

- VVN contribution to the 70th anniversary of the Mössing general strike

- Anna Felsinger, A little town offers resistance to fascism- anti-fascist blessing or communist curse? - General Strike in Mössingen, Germany on January 31, 1933 Essay, English

Notes / individual evidence

- ↑ Original leaflet : Call of the KPD Württemberg for a general strike against Hitler, PDF ( Memento of the original from April 8, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Frank Meier: The "red Mössingen" in a regional comparison - possibilities and potentials of regional history . In: Siegfried Frech / Frank Meier (Hrsg.): Teaching topic state and violence. Categorical approaches and historical examples . Wochenschau publisher. Schwalbach am Taunus 2012, pp. 292-316, here pp. 305-311.

- ↑ Manfred Maul-Ilg: Takeover and conformity at the local level ; in: Reutlingen 1930–1950. National Socialism and the Post-War Period. (P. 43) Published by Reutlingen City Administration / School, Culture and Sports Office / Local History Museum and City Archive , ISBN 3-927228-61-3 .

- ↑ Online reference to the Löwenstein brothers on a subpage of the Löwenstein-Förderverein initiative-loewensteinverein.de

- ↑ Short biography about Jakob Stotz on the web domain of moessinger-generalstreik.de , click on the first link to Jakob Stotz

- ↑ Memorial sites for the victims of National Socialism. A documentation, Vol. I, Bonn 1995, p. 61, ISBN 3-89331-208-0 .

- ↑ Fritz Wandel's curriculum vitae on Stadtwiki Reutlingen with references

- ↑ Demo for the Mössinger General Strike Day Article in the Schwäbisches Tagblatt from January 16, 2013 on the demonstration planned for the 80th anniversary in 2013, with a review of the previous anniversary demonstrations and an archive photo of the 1983 rally

- ↑ Jakob Textor's curriculum vitae and obituary article in the Schwäbisches Tagblatt from January 20, 2010. More detailed presentation as a reader's article on Zeit-online

- ^ Mössinger general strike: "Keep memories alive" - street should be renamed ; Article in Reutlinger General-Anzeiger on February 4, 2013 about the demonstration and rally on the 80th anniversary of the Mössing general strike

- ↑ A village in resistance , information on the content of the play, the cast and cooperation partners on the website of Theater Lindenhof (theater-lindenhof.de)

- ↑ Mössing General Strike comes on stage Article of the daily newspaper Die Welt from May 6, 2013 on the stage version of the Mössing General Strike material in the play A Village in Resistance

- ↑ Theater Lindenhof's official advance trailer for the general strike play "A Village in Resistance" , Flash video on youtube.com (about 7½ minutes)

- ^ "A village in resistance" premiered with 100 actors ( memento from September 27, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) by Kai-Uwe Brinkmann; Review of the performance of the play A Village in Resistance at the Ruhr Festival 2013 in the daily Ruhr Nachrichten on June 9, 2013 (accessed on June 12, 2013)

- ↑ Regional disobedience of Friederike Felbeck; Review of the performance of the play A Village in Resistance at the Ruhr Festival 2013 on the theater critic portal nachtkritik.de (accessed on June 12, 2013)

- ↑ Official press release : "BKM Prize for Cultural Education 2014" awarded (PDF file)

- ↑ Official website "Resistance is compulsory" :

- ↑ Record of the documentary “ There was nowhere nothing but here ” on www.imdb.de