Main Werra Canal

The Main-Werra-Canal is an unrealized construction project for a canal in Germany. It should connect the river system of the Upper Main with that of the Upper Weser in a navigable way. In the planning phase, which lasted over 300 years with interruptions, the project was also referred to as the Werra-Main Canal , Main-Werra-Weser Canal and Fulda-Werra-Main Canal , depending on the planning period and route variant. With a variant-dependent canal length of at least 284.5 kilometers and a height of up to 229 meters to be overcome, the Main-Werra Canal has always been one of the most ambitious waterway projects in Germany; but this was finally discontinued in 1961. The sister project between Danube and Main was implemented as the Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal in 1846 and again in 1992 as the Main-Danube Canal . There was no rudimentary realization of the Main-Werra Canal like the fossa Carolina of Charlemagne (Danube-Main) or the Landgraf-Carl Canal (Weser-Rhine).

Early expansion of Werra and Fulda

As natural waterways that lead from the north ( North Sea ) and west ( Rhine ) to the economically important area in the center of Europe, the Weser and Main played a special role in the history of inland navigation early on. Although there is a 250-kilometer low mountain range between the origin of the Weser in Münden and the Mainknie near Gemünden, with in some cases considerable differences in altitude, there have been numerous serious attempts to connect the two river systems since the early 17th century.

As much as the plans differed over the centuries, they all envisaged using Fulda or Werra as access to the Weser, whereby one or the other variant was preferred depending on the political constellation. For both, however, it was a prerequisite to make the original rivers of the Weser navigable as far as possible in the low mountain range regions of the Rhön and Thuringian Forest for barges and rafts.

Efforts to make the Werra navigable upstream from Münden can be found for the first time in a document on the removal of navigation barriers from the year 977. This made it possible to use the river as a transport route for goods from Thuringia such as woad , glass, textiles, wood and grain. Areas south of the Thuringian Forest also benefited from this natural waterway by initially taking their goods by land to the central reaches of the Werra and loading them onto barges or rafts that also crossed the Weser beyond Münden.

After Münden was granted the privilege of stacking rights in 1247 , all goods there had to be reloaded onto Weser ships. On the one hand, this helped the city to become very wealthy, but on the other hand it prevented rapid transport. Therefore the city of Coburg complained in a letter of March 20, 1577 about the hindrances in the reloading of goods on ships in Münden to the competent authorities in Kassel . The answer given in 1583 said succinctly that the Werra shipping was only allowed as far as Münden.

At the end of the 16th century, under Landgrave Moritz von Hessen-Kassel , the expansion work pushed by his predecessor Wilhelm IV continued, especially on the Fulda, despite considerable costs . The changed Fulda run was recorded on site plans. Four construction lots were set up between Mecklar and Melsungen , the management of which was carried out by experienced builders such as König and Vernucken. In addition to clearing the river bed, the expansion measures also included planting the banks and creating towpaths .

A report that was sent to the Landgrave in August 1601 shows that there were always major problems: “Thank God, the construction on the Fulda is still going on because the water (is) now as small as it is in many Years ago ". As the required building materials could no longer be transported on the river due to the unusually low water level and carts were not available for a short time, master builder König had to temporarily stop the work on his construction lot.

Despite the adversity, first reports appeared in 1602/1603 about a plan to make the Werra in the upper reaches "navigable for the benefit of lords and subjects".

During the Thirty Years' War work on Fulda and Werra slackened off considerably. In 1649 it was reported that “the bed of the Fulda river was badly muddy and it was hardly possible to get to Rotenburg by ship.” Shipping on the Werra to Wanfried on the border with the Duchy of Saxe-Gotha and Altenburg also declined during this time . Work to make the course of the river navigable via Wanfried to Meiningen was initially suspended.

Work on Fulda and Werra continued only hesitantly after the war. Even when, in 1658, Duke Ernst I of Saxe-Gotha and Altenburg made an offer to the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel Moritz if he might not “send in capable carpenters at [government] expense who, with such cooperation, would build a few of our locks to find out about the work so that afterwards you could continue your lover's lock work all the better. ”In order not to weaken the economic position of their border port, Hessen-Kassel was no longer interested in expanding the Werra beyond Wanfried. The landgrave rejected the duke's request on the grounds that this project appeared "quite difficult, at least doubtful".

First canal construction plans 1658–1669

Zeil am Main - Königshofen - Untermaßfeld

Duke Ernst I of Saxe-Gotha took over the joint government of the country with his brothers in 1618. In 1644 he inherited parts of the principality of Eisenach , 1660 county districts of Henneberg and 1672 Altenburg and Coburg .

His offer to the Landgrave of Hessen-Kassel in 1658, with the help of his experts, but at his own expense, to promote the expansion of the Werra through his land, shows his keen interest in a navigable trade route to the north. Unimpressed by the landgrave's harsh rejection, Ernst I began a little later to explore a possibility of building a canal from the Main into the Werra near Themar . 1660 musings took concrete shape, as well as the first possible route: From Zeil am Main , in turns over Hofheim to Konigsberg , continuing through the Brambacher forest and the giant hotel by over Stadtlauringen , Sulzfeld , Königshofen , Mellrichstadt and Bauerbach after Untermaßfeld to the Werra.

Since the canal path to be examined was initially to go through the Schmachtenberg office, i.e. through the prince-bishop's Bamberg and Würzburg region , he asked the Bamberg prince-bishop Philipp Valentin Voit von Rieneck and the Würzburg bishop Johann Philipp von Schönborn for permission to have measurements taken :

“To the grace of Mr. Bishop at Bamberg. PP We have no doubts E. Ldn. the common Wollfarth and the subjects are meant to be promoted next to us. When then it became known how by means of the ship type trade and change, also removal and supply could be made more convenient, and therefore in many places in and outside of the empire were flowed together for good use: as if we had advised the proposal especially because of the state of Franconia A poor man would like to be guided by mine into the Werra, want to appear in a way that is far from different people who want to be practi-cirlidi, and thereby want to gain a noticeable benefit to those who are adjacent to the abundance given by God in all kinds of necessities. […] We give ourselves a friendly consent to one or the other case, and stay, etc. Date Fridenstein on July 29, 1661. "

A similar letter was sent to the Würzburg bishop. After a few weeks, Ernst I received friendly replies from both Bamberg and Würzburg with the required patents for safe conduct , but Prince-Bishop Philipp Valentin openly expressed his doubts about the feasibility of the plan. On September 30, 1661, Duke Ernst asked his and the Bamberg and Würzburg subjects, referring to the patents, to support his surveyors in every way and immediately sent them for a “simple general survey of the site in question”.

The investigation of variants of the canal stretch lasted until May 1662. The report of the chief forester Christian Ritter from Königsberg, who was in charge of the inspections, was submitted to Duke Ernst, including a colored sketch . After that, the canal from Zeil should be 149 kilometers long in innumerable turns. On November 24, 1662, the Duke sent the elector of Mainz the sketch of the map , reported on the results of the inspection and ended with the note: “A more detailed proposal is necessary!”, Which meant a shorter route.

Zeil am Main - Römhild - Untermaßfeld

Two years later, Duke Ernst had his surveyors Christian Ritter and Jakob Börner look for a shorter route for the canal. This time they received more precise instructions: "From Zeil towards Bettenburg, from there to Manau and Schweinshaupten, past Römhild, towards Maßfeld". The mayor of Königsberg, Dampfinger, directed the work himself. These measurements did not show any positive results.

A new survey of the area by the clerk von Heldburg Ritter, the Jägermeister Trunßes and his brother was ordered. You should consider the option of leading the canal from the main into the spleen and from there into the litter . At the same time, completely different route ideas of the Duke emerged in the draft of a memorial for the Prince-Bishop. He suggested a canalization up the Main or up the Regnitz: "... and if you tried it, it might happen that you could also bring the Main against Staffelstein and Nuremberg". He also commented on the size of the ship for the first time and once again mentions Staffelstein as the starting point for the canal: “And if you have your princely Grace that the Canal would have to be as big as the ships would otherwise go up on the Main from Staffelstein, so that one would not have to have two ships! "

The measurements and search for a suitable transition between Zeil and Untermaßfeld, which lasted until April 1665, failed in any case. The heights at Trappstadt and Sternberg were described as insurmountable. Another, the fourth survey attempt in May 1665 failed, after which Duke Ernst was finally convinced of the impracticability of the canal in this way.

Gemünden am Main - Königshofen - ice field

But Ernst I. had not given up completely. In 1667 he tried to find a completely different solution, sometimes even by inspecting the site himself. The canal route should not begin in Untermaßfeld as previously planned, but far in the upper reaches of the Werra near Eisfeld , to then turn to the southwest and past Steinfeld via Gleicherwiesen to Heustreu to the Franconian Saale , and then its course to Gemünden am Main to use.

The forestry assistant Martin Neß and, after a meeting between Duke Ernst and Duke Friedrich Wilhelm of Saxony-Altenburg in the spring of 1668, also his bailiff Friedrich Born were involved in the investigation of this route . The actual measurements were carried out by the tried and tested administrators Börner and Martin Neß. An interim report by the two mentioned a necessary overpass over the Weihbachgrund near Veilsdorf so that the water could be led over “on stone arches and earth poured onto them”. An expanded report followed in November 1670. In the meantime, Ernst I had asked Landgravine Hedwig Sofie von Hessen-Kassel how things were going about the navigable expansion of the lower Werra, but this was met with strict rejection by the Landgrave. This and the poor health of the Duke may have led to the ice fields route not being pursued any further.

Kulmbach - ice field

Before Duke Ernst his entire channel plans shelved put, he dealt in 1669 with another variant of a possible Main-Werra connection from Kulmbach about Kronach to Eisfeld, which until then shortest alternative.

Although he formulated the investigation order: “The master builder has to investigate that the Werra, as it falls on the Bürgerleiten in Ambt Eissfeld down near Schauenburg, on the same waterway and then into the Cronach in the Neustadt, [...] could even go there alone be brought via Culmbach, as can be known from the Franconian Charte “, but whether an inspection or an investigation was actually carried out is not proven. With the death of Duke Ernst I in 1675, interest in a waterway between Main and Weser died out, while the ambitious project of a Main-Danube connection between Bamberg and Kelheim came to the fore. The Ludwig-Danube-Main Canal was completed in 1846.

Resumption of planning from 1906

The Central Association for the Uplift of German River and Canal Shipping , founded in Berlin on June 25, 1869 (later Central Association for German Inland Navigation , merged in 1977 with the Association for Safeguarding Rhine Shipping Interests to become the Association for European Inland Shipping and Waterways ) soon established itself for the creation of a connection from south to north through the middle of Germany. Ernst I's 200 year old ideas were taken up again. In 1906, when construction began on the Ems-Weser Canal (later the Mittelland Canal ), the Central Association commissioned the Havestadt & Contag hydraulic engineering company in Berlin-Wilmersdorf to develop such a canal project. Two years later, Wolf from Hildburghausen took over the preparatory work for the construction of dams to regulate the water supply of a Main-Werra canal.

From political and economic circles on the Weser, the Association for Making the Werra Navigable was founded in Hanover in 1907 under the leadership of the Hamelin entrepreneur Senator FW Meyer. Since the then prince and later King Ludwig III. von Bayern suggested in 1910 to connect southeast Germany with a large shipping route from the Danube to the Main and further from the Main via the Werra to the Weser and Elbe with the seaports of Bremen and Hamburg , the association shifted its focus to continuing the Werra as a canal to the Main and changed its name to Werra-Kanal-Verein . This in turn commissioned the two Berlin engineers Christian Havestadt and Max Contag to work out a corresponding preliminary design.

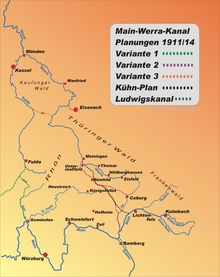

In 1911, Duke Carl Eduard von Sachsen-Coburg and Gotha invited the "Great Committee" from the Central Association and the Werra Canal Association to a Werra Canal meeting. It met on July 29th in the Coburg town hall , where Crown Prince Ludwig of Bavaria also gave a speech. Here Max Contag, who was commissioned by both associations with the planning, gave a lecture for the first time on the subject of the connection between the Coburg Lands and the planned Werra-Main Canal . At this meeting, Contag also explained several possible routes of a canal between the Main and Weser:

Option 1: Gemünden - Fulda

In this route variant, it was initially assumed that the Fulda should be made navigable to the city of Fulda and the Fliede flowing into the Fulda and, connected by a short canal, the Kinzig up to its confluence with the Main in Hanau . The Kinzig was navigable as far as Gelnhausen in the Middle Ages , but river navigation was given up in the 16th century because of the construction of mills, the unprofitable nature of the river and the silting up of the river. A canal should then branch off south of the watershed and allow shipping to the Main near Gemünden via the Sinn to be expanded. For the connection to the Main-Danube Canal, the ships would have had to go back up the Main to Bamberg after descending the Main. This line would have been 39 kilometers longer than the Werra-Itz line. In order to overcome the height between lilac and sense, a tunnel was planned in the apex posture. Seven locks and a lift were then to be built in the Sinn Canal.

Option 2: Bamberg - Meiningen

From Bamberg, this route variant should lead a short stretch of the Main to Breitengüßbach and from there the Itz up to Untermerzbach . Subsequently, a canal via Heldburg , Römhild , Ritschenhausen to Meiningen was planned. With this route, the Main-Werra-Canal would have been connected directly to the Main-Danube Canal, but the overall project to Münden would have included the construction of 45 locks, three lifts, one inclined level, four over a total length of 284.5 kilometers Canal bridges and two branch canals (to Eisenach and Coburg) required.

Option 3: Bamberg - Fulda

An alternative to variant 2 was also proposed for the direct connection of Kassel to the Main-Weser shipping route. As described there, first from Bamberg to Meiningen, then down the Werra to Dankmarshausen and with a canal branching off to the west to the Fulda near Bebra . The specialty of this variant was the Fulda-Werra Canal with a very high technical and financial effort. A height difference of 116.5 meters had to be overcome over a distance of 20 kilometers. This alone would have required five lifts and a lock. Alternatively, a tunnel with a length of 9.5 kilometers was examined. This would have made it possible to set the apex posture 96 meters lower and would have managed with just one elevator and one lock. This variant was immediately rejected due to the significantly higher demands.

Tunnel solution and economy

The Canal Committee met again on February 25, 1913 in Coburg. For the first time, a canal tunnel for overcoming the mountains between Römhild and Ritschenhausen was proposed as the cheapest solution. The time problem of crossing a canal was also clearly addressed: “The transport duration, including three days of loading time and five days of unloading time for the journey from Herne to Nuremberg and back, should be estimated at 40 days. According to this, a ship could make six trips a year and carry 3,600 tons of coal = 360 wagons to Nuremberg. "

The generation of energy in sewer operation was also an issue. It was raised that there might be difficulties in selling electricity because municipal and private power plants would be threatened with closure due to sales difficulties. The strategic (military) importance of the Main-Werra-Weser Canal for the interests of the empire was also pointed out. The committee finally decided to give Havestadt & Contag the contract for the preparatory work for the Bamberg-Meiningen canal project for 15,000 Reichsmarks .

In order to be economical, the Main-Werra Canal should be designed for the 1000-tonne ship. This would have assumed that the Oberweser had to be canalized with existing water levels of 1.00 to 1.20 meters. The existing Main-Danube Canal was also insufficiently dimensioned. The corresponding canalization of the Werra and the Itz were assumed. In order to justify these enormous requirements, the following arguments were put forward: With the Main-Werra Canal and the expansion of the Main-Danube Canal, the shortest waterway connection between the Danube and a North Sea port will be realized and a purely German waterway will be created. The project was also founded with the fight against unemployment. It was expected that larger quantities of potash salts would be transported from Thuringia to the north and south, phosphates to the potash works in Thuringia, agricultural products to Thuringia and lignite from northern Hesse to the south.

Max Contag, who also spoke alongside Ministerial-Conductor Sympher at this meeting of the committee in Coburg, seemed to be rather skeptical about the whole project. Nevertheless, immediately before the outbreak of World War I, he followed up with a more detailed plan. However, the beginning of the war prevented the continuation of his work.

Further planning 1914–1917

Before the beginning of the First World War, the royal real teacher and geographer Franz Kühn from Bamberg published a study on sewer planning that was highly regarded in his hometown, in which he propagated a completely new route, namely starting on the Main below Banz ( Lichtenfels ) via Kaltenbrunn , Seßlach , Dietersdorf , Heldburg, Römhild to Untermaßfeld, a route that included the existing rivers of Itz, Rodach, Kreck and Milz.

Kühn envisaged the expansion of the Bibra valley with a lift and another two lifts to the watershed of 358 meters in front of Westenfeld near Ritschenhausen. It should then go down through the Hutschbachtal with three lifts from Römhild to Heldburg. Alternatively, he took up Contag's idea of a nine-kilometer-long tunnel project, similar to the previously implemented French tunnel canals. Then the canal with six locks should follow the Rodach , which flows into the Itz at Kaltenbrunn , and from there down the Itz and from Hallstadt following the Main to Bamberg. This plan with its calculations and drawings should be used during a visit by King Ludwig III. will be presented in Bamberg. The visit did not take place due to the outbreak of war.

In 1916, Senator Meyer from Hameln, the chairman of the Werra Canal Association, published a memorandum to announce new considerations on the canal's line and discussed the lifting works and dams for the water flow. A new feature was a dam near Weißenbrunn , in which "up to 35 million cubic meters of flood water can be stored". In 1917 Meyer dealt with the subject of dams in a second publication.

Planning started again from 1918

In 1918, King Ludwig of Bavaria again approved a plan to connect a Main-Werra Canal near Bamberg to the Main-Danube Canal. Wolf, who had already received a planning contract in 1908, published the results of his investigations in 1919. Wolf assumed that the "bulk goods pass from the railroad to the waterway". In his publication he campaigned for the implementation of the tunnel project near Ritschenhausen and pointed out that the dams he had planned could not only provide energy, but also weaken the floods that regularly struck places in the Thuringian Forest and Franconian Forest. On the subject of the Coburg branch canal, he remarked: "Coburg is branching off from the apex position at Rodach, a branch canal of 24 km length that reaches the city mentioned in a horizontal route without a lock." He expected from an Itz dam at Waltersdorf (Rödental) that he had planned a storage volume of 40 million cubic meters, apart from the dewatering of the branch channel, an annual electricity generation of 4,640,000 kilowatt hours.

Government architect Franz Woas contradicted all previous plans in 1921 with regard to the procedure and the alignment of a canal and presented a new route: Bamberg - Rossach - Coburg - Rodach - Hildburghausen - Themar - Ritschenhausen. He was the first to include Coburg in the direct canal management.

Preparatory work office Eisenach

After the First World War, the expansion of the waterways became the responsibility of the German Reich . In order to be able to resume planning for a Main-Weser connection, a corresponding preparatory work office was set up in Eisenach in 1921. The management of the office was the hydraulic engineer Johann Innecken. This department of the Reich was active with a long interruption from 1924 to 1937 until the first years of the Second World War and was concerned with examining and concretizing the variants of a canal connection between Weser and Main proposed in the past.

Contag report

In this context, she again had Max Contag draw up a comparative report on the implementation options for the Main-Werra-Weser connection and one that includes the Fulda. Contag preferred the connection between Main and Werra to the Main-Fulda variant.

According to the report, both routes are roughly equivalent, but they differ in terms of elevation. The Werra race leads over the ridge of the Gleichberge , which is more difficult to negotiate than the ridge between Fulda and Kinzig, but compared to the Fulda race it has a much more favorable connection to the Obermain. In addition, the Werra is already largely expanded for shipping as far as Meiningen.

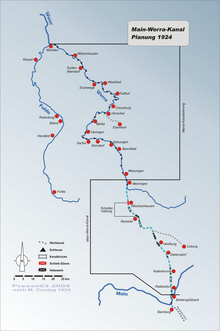

In his “Great Memorandum”, published in 1924, the connection of the Weser with the Main-Danube Canal , Contag published all the details of the canal construction with tables, drawings and a step-by-step plan showing the canal line according to the latest planning. Contag now also emphasized that "the economic importance of Coburg cannot be misunderstood" and devoted a separate chapter to a branch canal. Contag no longer planned a vertex tunnel. He planned a total of 49 locks for the entire 276.38 kilometer long canal from Breitengüßbach to Münden. The canal line should run between Breitengüßbach am Main and Untermaßfeld an der Werra via Rattelsdorf , Lahm , Kaltenbrunn , Dietersdorf , Autenhausen , Heldburg , Seidingstadt , Römhild, Haina and Ritschenhausen.

The planning began with the direct confluence with the Main-Danube Canal near Bamberg at a geodetic height of 242.80 m above sea level. NN and ended in Hann. Münden at an altitude of 117 m above sea level. NN. The ascent from the Main via the Itz to the 17-kilometer-long apex posture at Ritschenhausen was 113.2 meters over a length of 71 kilometers. The descent to Münden was 197 kilometers long and covered an altitude difference of 239 meters. Since a long construction period was to be expected, Contag submitted a main draft, which provided for the entire expansion for the 1000-t ship, and a restricted draft. He designed the waterway for the 600 t ship, but the structures for the 1000 t ship.

Intended structures

Barrages

Contag provided for a total of 41 control barriers for the expansion of the Werra to Meiningen and the Itz expansion. These should consist of a combination of a roller weir , a fish ladder , a chamber lock and a power station . The width of the roller weirs with two openings should be between 19 and 40 meters. Contag planned the fish ladder in the pillar between the weir and the power station. Mortise gates were provided for the lock chamber with a length of 110, a width of twelve and a jamb depth of three meters . In the descent of the Main, eight locks were to be designed as economy locks . Power plants were only planned in the 33 lowest barrages of the Werra. Contag expected an annual electricity production of 243.3 million kWh. The power station and lock “Last Heller” at about Hedemünden on the Werra were built in the 1960s in line with Contag's control barrage.

Inclined plane

A special boat hoist was with Ritschenhausen as transverse inclined plane provided to the height difference of 62 meters between the final attitude on the Werra side and the summit level to bridge at Ritschenhausen. The solution proposed by Contag was not about the already widespread "ship railway", in which the ship was moved over land on a rail-bound transport car, but a ship trough similar in size to a lock chamber, filled with water between a lower and an upper waiting basin should commute. The lifting distance was about 620 meters with an incline of 1:10. The entire trough device was to rest on eight axles on 16 double wheels and be moved with the help of counterweights at a speed of 0.5 meters per second. The lifting time should be around 30 to 40 minutes. A ship lift of this type was implemented in Arzviller / France , for example .

Lifts

In order to be able to compensate for larger differences in height in the descent of the Main, Contag planned three ship lifts with vertical conveying. With a lifting height of 38 meters, the hoist at Haina was the largest. As a counterweight lift with a ship's trough made of 8 centimeters thick sheet metal with a usable length of 110 and a clearance of 12 meters, it would have allowed a lock time of around 30 minutes. The lift should be carried out by a spindle drive and counterweights hanging on 300 wire ropes. The total weight to be lifted was given as 4,500 tons. The propulsion should be accomplished by motors. A building with a similar construction is the Niederfinow ship lift from 1934. The two other lifts near Heldburg were supposed to have a lifting height of 14.5 and 13 meters with the same trough size and were equipped with a balance beam system.

Canal bridges

In the apex position between Ritschenhausen and Haina, the longest of three planned canal bridges was planned with a length of 473 meters over the Bauerbach valley . A concrete construction with a vaulted substructure was planned. The other two bridges should have a length of 158 and 110 meters. In the case of a direct connection between the canal and the Main-Danube Canal, another 130-meter-long bridge was to be built over the Main. The cost of this bridge alone was calculated at 800,000 Reichsmarks.

Dams

A major problem with the canal project was the water supply for the apex. Two variants were considered for this. One provided for a water supply through several dams , as Senator Meyer from Hameln already announced in 1916 and 1917 in his two above mentioned. Had described the report, assuming a nine-kilometer tunnel in the apex posture. To this end, a large dam was to be built in the Itz area north of Coburg. The accumulation at the barrier should be 38 meters, so that the water level would have reached Almerswind . Meyer stated that the storage space was up to 45 million cubic meters. Pumping stations were supposed to transport the required water from this Itz dam via the individual sections of the main descent to the apex section. Meyer also mentioned advantages for the water supply of the city of Coburg and the flood protection of the region, which should not be underestimated.

The second variant, proposed by Contag in 1924, also provided for a water supply via a larger dam on the Itz, but was much more restrained in terms of dimensions. He moved the blocking point with the barrier wall below the inlet of the Effelder near the town of Schönstädt , thus reducing the reservoir planned by Meyer to 11.54 million cubic meters of water with a maximum storage height of 20 meters. This plan was approved because the reservoir blended in better with the landscape and required fewer relocations.

In fact, Contag's “Schönstädt-Speicher” was realized under the name “ Froschgrundsee ” in 1986, based on Meyer's argumentation of the improved flood protection in Coburg.

Branch canals to Eisenach and Coburg

The two branch canals to Eisenach and Coburg, which Contag included in its planning, were to be expected with their port facilities to the large structures. If the connection from Eisenach to the expanded Werra allowed only one solution, namely from Hörschel to the northern edge of the city, Contag presented six possibilities for the connection from Coburg to the Main-Werra Canal and evaluated them against each other:

The junction should be south of Streufdorf . The almost flat branch canal to Coburg was supposed to end after 22 kilometers in a terminal port north of the city. The route was planned past Roßfeld and Rodach via Großwalbur , Meeder , to the east of Glend. The terminal port could be built north of the Coburg districts of Cortendorf or Neuses, although the latter solution would have required a lock step of eleven meters at Glend to compensate for the canal gradient. Nevertheless, this would be preferable because of the railway connection in Neuses. In view of the construction costs of 12 million Reichsmarks just for the canal, Contag asked whether, under these circumstances, it would not be possible to do without a city harbor if it was possible to meet the city's transport needs in some other way. He suggested alternatives:

- Execution of only seven kilometers of the branch canal to Rodach with the establishment of a transshipment port and rail connection to the existing railway to Coburg.

- Establishment of a transshipment port for Coburg on the main canal near Streufdorf and extension of the railway until then. Contag saw this alternative as particularly cheap, because Coburg can, incidentally, claim the installation of such a transshipment port on the main canal at Reich costs for itself [...] if the state's own water from the Itz, which is needed for the canal feed, is available to the Reich represents.

Contag saw further alternatives in connection with Coburg's canal 16 kilometers south of the city near Kaltenbrunn:

- Canalization of the Itz over a length of 16 kilometers and creation of a terminal port south of the city of Coburg. However, he raised concerns that this would be technically feasible, but the expense would be very high, as five locks would have to be built and eight existing mills would have to be shut down or converted. Even if the left bank of the valley edge has already been used by road and rail, one comes to the conviction that making navigable can only be carried out on the right edge of the valley in a slim line within the valley floor.

- Branch canal of five kilometers in length to Rossach with a transshipment port there with a siding, whereby the 12.8 kilometer long existing railway line is completely sufficient to reach and develop the economic area of Coburg, not to mention the considerably lower construction costs .

- Contag saw the most significant cost savings in extending the line from Rossach to Kaltenbrunn and setting up a transshipment port there for Coburg.

Finally, Contag came to the recommendation to forego a branch canal entirely and to prefer a transshipment port in Streufdorf connected to the railway. The fact that he preferred to advertise rail solutions shows that in 1923 the railways were assigned a more important function for economic development than shipping.

Other interests

In addition to the Werra Canal Association, there were two other interest groups who tried to establish a north-south shipping connection. In 1921 the "See-Fulda-Main-Canal Association" was established in Fulda, preferring a connection between Fulda and Main. The association commissioned the Frankfurt engineer Hermann Uhlfelder to re-plan this canal project, which was proposed in 1911. At the same time, another interest group was formed in Limburg an der Lahn , taking up a concept that had been developed under Landgrave Karl von Hessen-Kassel 200 years earlier: the canal connection from the Fulda via the Schwalm to the Lahn .

Great Depression 1929

The final cost estimate for the construction of the Main-Werra Canal with all main and ancillary facilities resulted in total expenses of 320 million Reichsmarks. The annual operating costs were estimated at 375,000 Reichsmarks, almost a third of which would have had to be spent on the canal's water supply.

Due to the global economic crisis that began in 1929, there was a lack of funds and planning was suspended until further notice. The preparatory work office in Eisenach was closed. Shortly after the seizure of power of the NSDAP another meeting in Coburg in the hotel "Excelsior" took place despite the difficult financial situation on 11 March 1933 on the invitation of the now newly occupied Werra-channel association. An excursion for the participants led along the course of the planned branch canal and part of the main route from Coburg via Rodach, Römhild, Ritschenhausen, Untermaßfeld to Meiningen, where the conference was concluded.

In 1936, the then Prime Minister of Thuringia, Willy Marschler, personally approached Hitler with the request, despite the armament, to include the canal project in the Reich budget, as the canal route should also go through Thuringia. A few months later, the preparatory work office in Eisenach resumed its activities in 1937.

Canal conference in Coburg 1938

From September 22 to 24, 1938, the “Werra Canal Association for Safeguarding Water Shipping Interests” held a “Weser-Werra-Main Conference” in Coburg. 172 experts, journalists and state representatives took part in order to advance the Main-Werra-Canal project. In the specially published conference magazine Die Weser , the mayor at the time, Wilhelm Rehlein, pointed out in his welcoming address that the Weser-Werra-Main project […] is of great importance for our Coburg economic area […] as the long-awaited connection through the canal to the great waterways Weser and Danube.

The managing director of the association, H. Flügel, stated in his welcoming speech that the previous plans and the work already in progress are not sufficient, but that the expansion must reach directly into the potash area. [...] 1938 brought Austria back to the Reich , which meant that not only the further expansion of the Rhine-Main-Danube Canal, but also the connection of the Weser and Werra with the Main, gained significance that went far beyond the previous framework. The Reich Minister of Transport Julius Dorpmüller , who was invited to the conference, expressed it more clearly by pointing out that the Werra-Main Canal is a problem, the importance of which is not limited to the direction of the peace economy. The aim is to create a purely German large shipping route away from the border from the North Sea to the Hungarian border and thus further to all Danube countries. This major borderline goal [...] has now come to the fore for national-political reasons.

Large potash deposits were located roughly in the middle of the now required 1,336-kilometer-long waterway through Germany . Their harvest should be able to be transported quickly, cheaply and in large quantities both south and north. On the other hand, there was an urgent need for a cheap transport connection between Linz and Salzgitter , the two large locations of the “ Hermann Göring Works ”, which were currently being set up .

At the Coburg Canal Conference, no firm contracts were concluded, nor were new variants for routing the Main-Werra Canal presented. It was limited to the presentation of all previous plans and finally invited the participants to a tour of the planned branch canal route. A report later said: The cars stopped for the first time behind the barracks. Senior building officer Innecken points to the last houses in Neuses, indicating that the canal begins there, runs along the valley and past the Meederer bridge, leaving Rodach on the right, in Streufdorf opens into the actual Werra-Main canal ...

Establishment of the preliminary work office in Coburg

The Coburg Canal Conference in 1938 immediately set things in motion. The need to find more cost-effective ways of realizing the canal and thus to be able to implement the project in a shorter time prompted the upper waterway authorities to set up another preparatory work office in Coburg, which is independent of Eisenach. A report by the Coburger Tageblatt said: The importance of the Weser-Werra-Main Conference was subsequently crowned by the fact that the immediate goal of starting the preparatory work for the Werra-Main Canal soon afterwards, on December 1, 1938, namely, as had already been envisaged, the expansion of the preparatory work office in Eisenach and the establishment of a new preparatory work office in the conference location Coburg. In the house at Hohe Strasse No. 30 , the office began its work on the scheduled date under the direction of Government Building Councilor Buzengeiger.

In addition to reviewing the existing sewer planning, the preparatory work also had to face resistance. The Upper Nature Conservation Authority in Berlin wrote to the regional presidents in Erfurt and Hildesheim as well as the Thuringian Ministry of the Interior in Weimar on July 24, 1939 , pointing out that the canalization [...] would involve significant interventions in the outstanding landscape [...] [...] which will primarily occur where the river bed leaves and a special channel [...] is created. This problem was negotiated several times until the preparatory work offices were dissolved in 1942.

The Coburg line Lichtenfels – Untermaßfeld

On June 13, 1940, the city was informed that the Reich governor in Bavaria had commissioned the inspection of a Kaltenbrunn-Coburg canal (the Bavarian governor was Franz von Epp ). This was the alternative proposal with only 16 kilometers of branch canal compared to the Streufdorf-Coburg stretch of 33 kilometers, which Contag had already submitted in 1924. Buzengeiger initially endorsed the proposal after consulting with city officials.

Also on June 13, 1940, the Coburg Chamber of Commerce and Industry presented another, completely new proposal to the district president, the “Coburg Line”. The route should now lead from Römhild via Rodach to Coburg and on to the vicinity of Lichtenfels, where the canal could flow into the Main. Actually, the IHK took up part of the plan by Franz Kühn from Bamberg from 1914, which had proposed integration into the Main near Banz. The canal, which runs directly past Coburg, should later have a connection via Bayreuth to the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia , suggested the Chamber of Commerce.

It was a characteristic of this line to dispense with the two branch channels under discussion (Streufdorf-Coburg and Kaltenbrunn-Coburg) in favor of a combination of both. The following canal routing was clearly visible on the submitted plans: Lichtenfels / Main (with port and elevator) - Buch am Forst - Scherneck - Stöppach - Haarth - Ahorn - Coburg Saarlandberg (formerly Judenberg) - Coburg Rummenthal - Neuses (with Coburg harbor) - Beiersdorf / Callenberg - Herbartsdorf - Gauerstadt - Rodach (with harbor) - Rudelsdorf - Streufdorf - Simmershausen - Gleichamberg - Römhild - Haina - Westenfeld - Jüchsen - Neubrunn - Ritschenhausen - Untermaßfeld on the Werra.

In mid-December 1940, the district president announced that the Reichsstatthalter had campaigned for the so-called Coburg line with the Reich Minister of Transport. The “ready-to-build design” was immediately tackled by the preliminary work office. The Thuringian potash industry supported the project with considerable financial resources. In the planning that followed, the capacity of the canal to accommodate 1,200-tonne ships was also increased. Another major change has been made. The vertex posture was reduced by 36 meters and thus its length was extended to around 71 kilometers. To achieve this, the long-discarded tunnel solution was used again. After all, the lifting height of the inclined plane could be reduced to 51 meters and that of the hoist at Haina to 30 meters. The planners abandoned the Itz dam in favor of one in the Werra area in order to supply the apex with water.

Buzengeiger ran the planning work of his office at full speed. In January 1941 he had 20 models made on a scale of 1: 2,500, including an eight-part plaster model of the Callenberg - Coburg - Scherneck canal route and a wooden model of a ship lift. The models were exhibited in the town's local history museum at the end of 1941.

The activities of the preliminary work department also had a strong influence on the planning of the Coburg building administration. On January 13, 1941, the authorities wrote to a property owner in Coburg: The property is located in the Rummenthal in the area of the Werra-Main canal project. It is to be expected that the property in question will be wholly or partially required by the Reich when the sewer project is carried out! It can therefore not be used for development until further notice.

The NSDAP was the same from the city building department on the renamed "Saarland Mountain" Judenberg a festival hall as a circle Forum plan, as opposed counterpart of the Veste Coburg . On the relevant development plan, the canal was already drawn in a representative manner below a parade area with an avenue rising from the station area. The new route of Reichsstrasse 4 was to lead along the canal. A landing stage at the foot of the Aufmarschallee was also planned.

In 1942, the preliminary work office completed its planning and presented the “ready-to-build design”. Shortly thereafter the office was dissolved. The development of the war did not allow further pursuit of the canal project.

Resumption of planning after 1945

The 1942 “ready-to-build” planning of the dissolved preparatory work office in Coburg was transferred to the now responsible water and shipping directorate in Hanover , which temporarily suspended the project in May 1949. In addition to the division of Germany, the reasons for this were the expected costs, which in April 1950 would have amounted to around DM 1 billion. With the price increase factor of 6.97% that was usual at that time, the realization of the project in 1990 would have cost over 14 billion DM.

Nevertheless, there were some attempts by advocates of the project not to let it be forgotten, for example by the former head of the Coburg planning office Buzengeiger, who took up the idea again on July 5, 1947. He asked Hanover how the canal should now run. The waterways directorate announced that the "planning ready for construction" of the preliminary work office would be checked again.

Changed Coburg line

It was not until April 15, 1950 that the canal project began to move again. At the meeting of the Coburg city parliament, it was decided to get the federal government to ensure that the Coburg efforts for a canal connection in the overall planning of the German waterways are not postponed in favor of competitors or completely discontinued. At this meeting, Lord Mayor Walter Langer suggested forming a working group from the cities of Coburg, Lichtenfels, Bamberg and Eschwege. Buzengeiger presented an "explanatory report" for this meeting, which in turn contained new ideas for planning. He moved the route further east with a port near Dörfles. A variant that will essentially be taken into account in later plans in 1960.

The changes mainly concerned the connection of the canal to the Main near Lichtenfels. Bunzengeiger feared that the elevator below Schloss Banz would come in contrast to Schloss Banz and Vierzehnheiligen. And that it is more and more difficult to realize a hydraulic structure of this size if it is only intended for one use, namely shipping. The expansion of a possible use in the energy industry and regional cultural area is desirable. He also explains that the canal with its approx. 3.3 × 10 m² water surface area [meaning the cross-section of the canal] is suitable for use as a storage tank. This storage facility [...] can be used for a pumped storage plant with the 64 m high gradient [near Lichtenfels] .

Further planned construction work

Buzengeiger himself spoke of major construction work that would have been necessary to realize his plan. Nevertheless ... the Coburg line should still be adhered to, because u. a. With its technical generosity, it contributes to ensuring that the Weser-Main waterway Bamberg-Bremen has considerable traffic in the competition between Bamberg-Mainz-Rhine estuary.

Buzengeiger's channel plan changes required additional structures:

- Several dams to cross different valleys would have been necessary, for example west of Roßfeld over the Rodachtal with a height of twelve meters, over the Lautertal with a height of six meters and over the Itztal near Dörfles with a dam height of even 18 meters.

- The lame back between the Krebsbach near Waldsachsen and the Rohrbach near Oberfüllbach should have been pierced. To make the necessary 45 meter deep cut, seven to eight million cubic meters of earth would have to be moved.

- The descent lift near Lichtenfels was supposed to cope with a difference in altitude of 64 meters. In order to prevent a line of sight with Banz Castle and to preserve the character of the landscape there, the elevator in Lichtenfels was to be built between Coburger Strasse and Schneybachtal.

- In order to be able to supply the necessary river water to the canal, Buzengeiger planned to build the canal dam through the Itztal as a dam. This would have created a seven-kilometer-long, 700-meter-wide reservoir with the possibility of generating 6.5 million kilowatt hours a year through an Itz power plant near Dörfles.

Final plans

On December 5, 1950, Federal Transport Minister Paul Lücke made a recommendation to the Waterways and Shipping Directorate in Hanover to keep the planned route clear. In the event of the unification of Germany, work on the project should be resumed. In contrast, the city of Coburg, knowing that a future canal would by no means run through the city, finally cleared the development for the "Hörnleinsgrund project" in 1956, which was blocked because of the canal.

At the same time, the Lichtenfelser Tagblatt ran the headline on January 13, 1956: German inland shipping connection should touch Lichtenfels - ship lift or lock system - but not envisaged before 1968 . The newspaper summarized the result of a discussion of the local planning office with representatives of the authorities in the Lichtenfels town hall, which primarily concerned the question of which location a ship lift should be built at or whether a lock staircase should be preferred. Eggert from the district planning office of the government of Upper Franconia raised the question of the economic viability of the canal. Despite all the zeal for planning, the meeting ended with the conclusion that, of course, the eastern zone problem had to be solved first .

The local planning office in Lichtenfels created a city map in March 1958 that showed the section of the newly planned Main-Werra Canal that affected Lichtenfels. Then there were two projects to choose from:

- Canal guidance 300 meters below the Main Bridge starting from the regulated river bed of the Main towards the Herberg, overcoming the slope with a vertical lift on the Herberg towards Itzgrund.

- Canal course between the Bürglein district, which still belongs to Lichtenfels, and Coburger Strasse, overcoming the incline by means of a lock staircase.

The decision for the second variant was made in 1961. According to a plan drawn up by the Lichtenfels district building authority in February 1961, the canal should no longer run from Lichtenfels directly into Itzgrund, but instead to the right between Forsthub (Grub am Forst) and Ebersdorf in the direction of Rodach. This canal planning was coordinated with the Waterways and Shipping Directorate South in Würzburg and was the last published version.

In 1970 the Waterways and Shipping Directorate South informed the City of Coburg that the whole matter would no longer be pursued because of the cross-border planning , but the Waterways and Shipping Directorate in Hanover confirmed on November 12, 1998 that the planning had been formally suspended is not evident from the files .

literature

- Georg Aumann: Coburg and the Main-Werra-Weser Canal. The story of an idea that never came to fruition . In: Coburger Geschichtsblätter 7, 1999, 1, ISSN 0947-0336 , pp. 9-36.

- Albrecht Hoffmann : Weser-Main Canal: The old dream of a waterway through the Hessian mountains . In: Frank Tönsmann (Hrsg.): On the history of the waterways, especially in Northern Hesse . Herkules-Verlag, Kassel 1995, ISBN 3-930150-03-4 , ( Kasseler Wasserbau series Mitteilungen 4), pp. 83–110.

- Martin Kuhn: The Main Werra Canal. A forgotten project from the 17th century in Upper Franconia . In: Geschichte am Obermain 4, 1966/67, ZDB -ID 958655-6 , pp. 111-120.

- Ronald Paul: The Werra-Main Canal . In: Frank Tönsmann (Hrsg.): On the history of the waterways, especially in Northern Hesse . Herkules-Verlag, Kassel 1995, ISBN 3-930150-03-4 , ( Kasseler Wasserbau series Mitteilungen 4), pp. 185–199.

Web links

- Notes in Schatzsucher.de

- Report in Oberfranken.de (PDF file; 2.25 MB)

- Report in the Hersfelder Zeitung - special supplement Mein Heimatland (PDF file; 97 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Otto Hennicke: Chronicle of attempts to make the Werra navigable ; from Thüringer Heimat , No. 3, Erfurt 1956, pp. 162–176.

- ↑ Erwin May: Münden and surroundings , Hann. Münden 1980.

- ^ Paul Wegner: The medieval river navigation in the Weser area ; from Hansische Geschichtsblätter 19, Cologne 1913, p. 113.

- ^ Werner Engel: Joist Moers in the service of Landgrave Moritz von Hessen. A contribution to his late surveyor activity and at the same time to the shipping history of the Fulda ; in Hessisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte 32, Hessisches Landesamt für Geschichtliche Landeskunde, 1982, pp. 170–171.

- ↑ a b Marburg State Archives 4a 39/54.

- ↑ State Archives Marburg 40d 9/47.

- ^ Franz Kühn: The Main-Werra connection. A historical and economic study with special consideration of Bamberg's interests . Bamberg 1914.

- ^ Paul Görlich: From the history of the Fulda shipping ; from Mein Heimatland 35, Bad Hersfeld 1992, pp. 21-22.

- ↑ Otto Hennicke: Chronicle of the attempts to make the Werra navigable ; from Thuringian homeland , issue 3, Erfurt 1956, p. 164.

- ^ Herbert Leifer: The planned Weser-Main Canal ; from Die Weser 4, Bremen 1925, p. 267.

- ^ Franz Kühn: The Main-Werra connection. A historical and economic study with special consideration of Bamberg's interests . Bamberg 1914, p. 14.

- ^ Franz Kühn: The Main-Werra connection. A historical and economic study with special consideration of the interests of Bamberg , Bamberg 1914, p. 29.

- ^ Martin Kuhn: The Main Werra Canal ; Pp. 112-114.

- ^ Martin Kuhn: The Main Werra Canal ; P. 115.

- ^ Martin Kuhn: The Main Werra Canal ; Pp. 115-117.

- ^ Georg Aumann: Coburg and the Main-Werra-Weser Canal ; P. 113.

- ↑ a b Martin Kuhn: The Main-Werra Canal ; P. 117.

- ^ Georg Aumann: Coburg and the Main-Werra-Weser Canal ; P. 12.

- ↑ Reinhard Grosscurth: The plan of a Werra-Main canal. An almost forgotten piece of economic history ; in: Care and creation for the Weser 9, Bremen 1970, pp. 17 and 18.

- ^ Hans-Jürgen Ast: Making the Werra navigable ; in: Hersfelder Zeitung November 8, 2006.

- ↑ a b c Max Contag: The connection of the Weser with the Main-Danube Canal ; in: Die Bautechnik 3rd special issue, Berlin 1924.

- ↑ Harald Sandner: Coburg in the 20th century. The chronicle of the city of Coburg and the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha from January 1, 1900 to December 31, 1999 - from the "good old days" to the dawn of the 21st century. Against forgetting . Verlagsanstalt Neue Presse, Coburg 2002, ISBN 3-00-006732-9 , p. 46.

- ^ Max Contag: About the connection of the Coburger Lande to the planned Werra-Main Canal ; in: Journal for domestic economy issue 16/1911, Berlin 1911.

- ↑ Martin Eckoldt: Shipping on small rivers in Central Europe in Roman times and the Middle Ages. Writings of the German Maritime Museum 14, Oldenburg, Hamburg, Munich 1980, pp. 84–86.

- ↑ Ronald Paul: The Werra-Main Canal ; P. 185.

- ↑ a b c Ronald Paul: The Werra-Main Canal ; P. 187.

- ↑ Negotiating report on the meeting of the committee for the promotion of the project of a large shipping route from the North Sea to the Danube and to Munich-Augsburg on Tuesday, February 25, 1913 at 3 1/2 a.m. in the Coburg Railway Hotel , Hameln 1913. - Coburg City Archives A 5495.

- ^ Georg Aumann: Coburg and the Main-Werra-Weser Canal ; P. 31, footnote 13.

- ^ Georg Aumann: Coburg and the Main-Werra-Weser Canal ; P. 31, footnote 14.

- ^ Martin Kuhn: The Main Werra Canal ; P. 111.

- ^ FW Meyer: Memorandum on the project of a large shipping route from the North Sea (Bremen) through Thuringia to Bamberg and Nuremberg with the connection to the Rhine-Weser-Hanover Canal and the Main, in connection with the generation of significant hydropower in the Werra and Main area through the construction of dams with description and explanations , Hameln 1916. - Coburg City Archives A 5495.

- ^ FW Meyer: Report on the preliminary work of the dams - projects in the headwaters of the Werra, Fulda and Itz in connection with the draft of the Weser-Werra-Main waterway , Hameln 1917. - Coburg City Archives A 5495.

- ↑ Wolf: The hydropower of Thuringia in the Werra area. Weser-Werra-Main Canal, dam and hydropower systems ; in: Das neue Thüringen Heft 4, Erfurt 1919. - City Archive Coburg A 5495.

- ^ Franz Woas: The Weser-Main-Danube Canal ; in: Inland Shipping Volume 27, Issue 6, 1926.

- ^ Johann Innecken: The Weser-Main Canal ; in: Die Weser 1, Bremen 1922, p. 59.

- ↑ Ronald Paul: The Werra-Main Canal ; P. 189.

- ↑ Ronald Paul: The Werra-Main Canal ; Pp. 189, 191.

- ^ Georg Aumann: Coburg and the Main-Werra-Weser Canal ; Pp. 18-19.

- ↑ Ronald Paul: The Werra-Main Canal ; Pp. 189, 192.

-

↑ Ronald Paul: The Werra-Main Canal ; Pp. 189–192, 194.

Georg Aumann: Coburg and the Main-Werra-Weser Canal ; P. 18. - ↑ Ronald Paul: The Werra-Main Canal ; Pp. 193, 195.

- ^ Georg Aumann: Coburg and the Main-Werra-Weser Canal ; P. 17.

- ↑ a b c d Ronald Paul: The Werra-Main Canal ; P. 195.

- ^ Georg Aumann: Coburg and the Main-Werra-Weser Canal ; Pp. 21-22.

- ^ Georg Aumann: Coburg and the Main-Werra-Weser Canal ; P. 23 and 24.

- ^ Hermann Uhlfelder: The Fulda-Kinzig- and the Sinn Canal from Zeitschrift für Binnenschifffahrt 29, Duisburg 1922, p. 221.

- ^ Georg Aumann: Coburg and the Main-Werra-Weser Canal ; P. 20.

- ^ Meeting of the Werra Canal Association in Coburg , Coburger Tageblatt of March 12, 1933.

- ^ Georg Aumann: Coburg and the Main-Werra-Weser Canal ; P. 24.

- ^ The Weser , monthly publication of the association for the protection of Weser shipping interests. V., 17th year, issue 9, Bremen 1938.

- ↑ Special supplement No. 22 to the Coburger Tageblatt - multi-page reporting on the Coburg Canal Conference, Coburg, September 24, 1938.

- ^ Georg Aumann: Coburg and the Main-Werra-Weser Canal ; P. 25.

- ^ Journal Die Weser , 17th volume no. 10 as well as files in the Coburg State Archives 11644.

- ↑ State Archives Coburg 11,636th

- ^ Reconstruction plans in the Coburg State Archives, collection of plans 1464–1467.

- ↑ a b Files of the Coburg City Planning Office.

- ↑ The lines are drawn on the corresponding measuring table sheets 1:25 000 with a red double line. - Coburg State Archives, collection of plans 1468–1471.

- ↑ a b City Archives Coburg A 10338.

- ↑ Coburg City Archives.

- ↑ a b Georg Aumann: Coburg and the Main-Werra-Weser Canal ; Addendum pp. 34–36.

- ↑ State Archives Marburg - W3-132 Han 58th

- ↑ Lichtenfelser Tagblatt January 13, 1956.

- ^ Archives of the Lichtenfels City Building Office.

- ↑ Archive of the district building office in the Lichtenfels district.